Abstract

The tradition of storytelling is an integral part of Alaska Native cultures that continues to be a way of passing on knowledge. Using a story-based approach to share cancer education is grounded in Alaska Native traditions and people’s experiences and has the potential to positively impact cancer knowledge, understandings, and wellness choices. Community health workers (CHWs) in Alaska created a personal digital story as part of a 5-day, in-person cancer education course. To identify engaging elements of digital stories among Alaska Native people, one focus group was held in each of three different Alaska communities with a total of 29 adult participants. After viewing CHWs’ digital stories created during CHW cancer education courses, focus group participants commented verbally and in writing about cultural relevance, engaging elements, information learned, and intent to change health behavior. Digital stories were described by Alaska focus group participants as being culturally respectful, informational, inspiring, and motivational. Viewers shared that they liked digital stories because they were short (only 2–3 min); nondirective and not preachy; emotional, told as a personal story and not just facts and figures; and relevant, using photos that showed Alaskan places and people.

Keywords: Digital storytelling, Storytelling, Cancer communication, Community cancer education, Alaska Native, Indigenous research, Cancer education materials, Digital storytelling as adult education, Digital storytelling as health promotion, Cancer-related digital stories, Community focus groups

Introduction/Background

Cancer, considered as a rare disease among Alaska Native people as recently as the 1950s [1], is currently the leading cause of mortality among Alaska Native people [2]. The four most frequently diagnosed cancers among Alaska Native men and women living in Alaska are colorectal, lung, breast, and prostate [2] cancers. The burden of these leading cancers among Alaska Native people can be positively impacted by having recommended cancer screening exams [3] and engaging in healthy lifestyle choices [4].

Alaska Native cultures have long histories of sharing information and knowledge through stories based on personal experiences [5]. Stories continue to be used to share knowledge, to pass on traditions and cultural values, to establish one’s place in the world, and to entertain [6]. Community health workers (CHWs) in Alaska have identified storytelling as a pathway for connecting people, facilitating understanding, enhancing remembering, engendering creativity, expanding perspectives, envisioning the future, and inspiring possibilities [7]. Thus, using a personal story-based approach to provide information about cancer is grounded in Alaska Native traditions and has the potential to positively impact lifestyle behaviors and recommended cancer screening exams. Health communication materials that succeed in making information relevant through both cognitive and affective engagement have been shown to be more likely to be effective than materials that only use a cognitive approach [8–10].

Digital storytelling combines the tradition of oral storytelling with computer-based technology to provide a creative and engaging way for people to tell their stories and pass on knowledge and understandings. Additionally, digital storytelling is portable and accessible using web technologies and social media outlets. The potential for media sharing is continually expanding. Since 2013, digital stories, with storyteller written permission, have been posted on the Alaska Community Health Aide Program web page where they have received numerous views (http://www.akchap.org/html/distance-learning/cancer-education/cancer-movies.html).

Digital storytelling combines a person’s recorded voice with their choice of pictures, music, and transitions to create a short movie. In cancer education courses for CHWs in Alaska, digital stories were created using Movie Maker, the free Microsoft video-editing program, and an inexpensive snowball microphone. CHWs each designed and produced a 2–3-min heartfelt message during a 5-day, in-person cancer education course [11]. No previous computer skills were required for course participants. Course facilitators guided story creators to focus their cancer-related health messages by reflecting upon what they wanted community members to know and/or do as a result of watching their short movies. Additionally, participants were reminded that creating a digital story was their opportunity to tell their personal story in addition to relaying facts or information. As part of a story circle, each participant discussed her or his story idea with the group. Listeners were encouraged to provide helpful feedback using the following prompts: I really liked when you…, I want to know more about…, and If this was my story… As all CHW participants created their story, they were invited to visualize who they wanted to tell their story to and who they hoped would watch their story. This imagery helped to guide the storyteller’s choice of language, photos, and music. Through the process of creating and revising their digital stories, course facilitators watched participants reflect upon and make sense of their personal experiences.

Since its inception in the early 1990s, digital storytelling has gained momentum as a social advocacy tool [12, 13]. However, research into the effects of digital storytelling is sparse. Digital storytelling is a dynamic way for stories to be created and communicated, but its potential has yet to be fully realized within public health. A search of peer-reviewed journals revealed few digital storytelling research studies. Most articles were anecdotally focused upon practical tips for incorporating digital storytelling into the learning environment [14]. Some universities reported incorporating digital storytelling into diverse disciplines to support reflective practice, empathy, knowledge application, and deep learning [15–19]. Additionally, digital storytelling supported increased self-efficacy and empowerment [20, 21]. These attributes are widely considered essential for lifelong learning [22]. Utilizing digital storytelling as a cancer prevention health promotion strategy is an emerging practice. No research was found that assessed the engaging elements of cancer-related digital stories.

Research approaches that respect indigenous knowledge, voices, and experiences are advocated within the “Handbook of critical and indigenous methodologies” [23]. Culturally responsive research practices locate power within the indigenous community where research is conducted [24]. Digital storytelling as a methodology brings the power of the media into the voices and hands of community members.

In this paper, we describe community members’ response to viewing digital stories created by Alaska’s community health workers. This research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Alaska Area Institutional Review Board and the Southcentral Foundation (SCF) Executive Committee. Additionally, this manuscript was reviewed and approved by the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC) Health Research Review Committee (HRRC) on behalf of the ANTHC Board of Directors and the SCF Executive Committee.

Methods

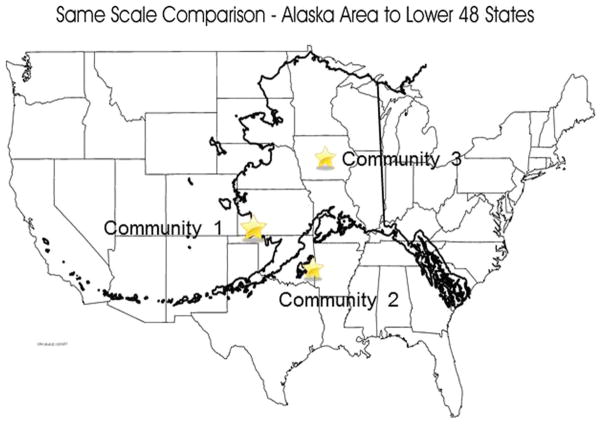

The principal investigator (PI) facilitated focus groups in three different Alaska communities to identify engaging elements of digital stories among Alaska Native people. To begin the process of establishing community focus groups, the PI (the primary cancer education and digital storytelling course instructor, known by all course participants) e-mailed 48 CHWs in rural communities across Alaska who had previously participated in the 5-day, in-person cancer education course and had created a personal cancer-related digital story. Out of 67 course participants from the cancer education and digital storytelling courses offered May 2009–May 2012, 19 people were lost to follow-up, including 1 person who died from brain cancer. At the time of focus group recruitment, contact information was available for 48 CHWs. As primary medical providers known and respected within their communities, CHW collaboration was fundamentally essential to facilitate effective community-based focus groups. Every Alaska community health clinic has a computer, and each CHW has an e-mail address. The e-mail invitation asked each of these CHWs if they would be interested in working with the PI to recruit community members and make arrangements for a focus group gathering to view and discuss community members’ ideas and perceptions about two to four digital stories created by CHWs across the state. Initially, ten CHWs responded to the e-mail invitation from the PI. Ultimately, three communities were selected based upon CHW availability to assist the PI with advertising, recruiting, and scheduling a community focus group as well as their geographic location throughout Alaska (see map).

Each of the three CHWs assisted with focus group recruitment via word-of-mouth, phone calls, and personal invitations to people who could provide diverse perspectives and viewpoints about digital storytelling during the group discussion. Additionally, CHWs created posters to advertise the focus groups, which were displayed in the tribal office and health clinic. CHWs arranged focus group locations to facilitate a comfortable environment for digital story viewing and discussion: the community tribal office (community 1), the health clinic meeting room (community 2), and the tribal house (community 3).

Each focus group was scheduled for 2 h. Depending upon group discussion and time available, between two and four cancer-related digital stories created by CHWs were shown. Digital story topics included tobacco cessation, colon and breast screening, and the importance of early detection and treatment of cancer. These topics were chosen as they directly related to the most common cancers among Alaska Native people. Each CHW story creator provided written consent to show their digital story as part of the focus group gatherings.

After viewing each story, focus group participants completed a written questionnaire. Participants then discussed the cultural relevance of the stories, engaging story elements, information learned, and their intent to change health behavior as a result of viewing the digital stories. To conclude the focus group gathering, participants discussed digital storytelling as a cancer communication tool and completed a written questionnaire about their overall experience with digital storytelling. The PI and/or a project team member took notes during all three focus groups.

Four members of the project team reviewed information from the written responses and focus group notes, first independently, and then collectively, to identify emergent themes. Thematic analysis was used to ground the analysis within the context of participants’ stated experiences [25]. Team members included co-instructors of the cancer education and digital storytelling course, a Community Health Aide instructor with evaluation expertise, and an experienced qualitative researcher living outside of Alaska.

Results

With help from the CHWs, a total of 29 adults participated in the focus groups. Participants included 26 Alaska Native people, ranging in age from 20 to older than 70, the majority (22) of whom was women (see Table 1 for additional detail).

Table 1.

Focus group participants

| Focus group | Community 1 | Community 2 | Community 3 | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of participants | 8 | 6 | 15 | 29 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 7 | 5 | 10 | 22 |

| Male | 1 | 1 | 5 | 7 |

| Ethnicity (self-identified) | ||||

| Aleut | 1 | 1 | ||

| American Indian | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| Athabaskan | 9 | 9 | ||

| Caucasian | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Gwich’in | 1 | 1 | ||

| Inupiat | 2 | 2 | ||

| Sugpiaq | 2 | 2 | ||

| Yupik | 8 | 8 | ||

| Age (years) | ||||

| 20–29 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| 30–39 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 40–49 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 50–59 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| 60–69 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 12 |

| 70 and older | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Have you had cancer? | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 0 | 7 | 8 |

| No | 7 | 6 | 8 | 21 |

| Do you know a person who has been diagnosed with cancer? | ||||

| Yes | 7 | 6 | 15 | 28 |

| No | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

On both the written questionnaires and during the lively post-viewing discussions, digital stories were described by Alaska focus group participants as being culturally respectful, informational, inspiring, and motivational.

“This type of testimony is so powerful it activates all of your senses for learning. The words and pictures draw you into the story and then you don’t even realize you are getting health information. It’s a good combination between personal story and health information. I loved how we were told about screenings…it was a call to action.”

Digital Stories Are Culturally Respectful

All focus group participants described digital stories as culturally respectful. These digital stories incorporated the CHWs’ dynamic lived experiences of culture and shared the diverse ways health is understood and transformed within the vibrant complexities of community. Although focus group participants were from different regions and backgrounds than the story creators, the digital stories were viewed as a respectful health messaging tool.

“Stories are how we always learn, makes it easier to listen and to remember…it’s good to see stories.” The stories talk about the human experience so even if we are from a different region or culture, we can relate because they are so real.”

Engaging Digital Story Elements

Viewers stated that they were drawn into the stories because they felt a connection to the storyteller. The use of photos from Alaskan communities particularly helped to captivate viewers’ attention. Participants also appreciated the real-life testimonial which was described as inspiring and motivational.

“These stories show that it can really happen to you… like a wake-up call about how we live.”

“These short stories are much more powerful than just telling people what to do or the facts. Let’s people use their own mind, get engaged, think about things for themselves. It evokes so much emotion and reflection that you don’t have to have the “you need to do this direct message”. That feels disrespectful. People’s stories speak to truth.”

Viewers described that they liked digital stories because they were

-

Short, only 2–3 min with a written script of approximately 250 words.

“The stories are short and sweet and to the point, grabs your attention.” -

Nondirective, not preachy.

“Storytelling makes it easier to hear the message. It touches people’s hearts.” -

Emotional, told a personal story and not just facts and figures.

“The stories are told in quiet ways not directive, this is much more powerful. They are personal- the people are real. You can tell they are speaking from their own feelings and experiences.” Relevant, using photos that showed Alaskan places and people. Community members were drawn into the short stories by the CHWs’ choice of personal photos, music, their own voice, and the heartfelt emotions expressed by the storyteller.

A Pathway for Conversations, Healing, and Transformation

Digital stories showed during the focus groups created an opening for lively post-viewing conversations. During the post-viewing focus group discussions, CHWs’ digital stories served as a catalyst for community members to tell their own experiences, stories, and personal reflections. Focus group participants described this sharing of personal stories as healing and transforming.

“Telling our stories helps us to heal together. Brings it out in the open so everyone can cry together…maybe we are scared or afraid but if we talk about it [cancer] we can be strong together.”

Increased Understanding

As a result of the invitational, nondirective digital story format, participants indicated that they experienced an increased understanding of cancer information.

“ [Digital storytelling] Evokes emotion that solidifies learning-memory. It opens your heart as well as your ears.”

On both the written questionnaires and during the focus group conversations, participants reported information or insights they had learned as a result of digital story viewing. The brief nature of the digital stories also prompted participants to ask questions to learn additional cancer-related information.

“Watching digital stories gives us an inside view on how cancer can effect a family and the community and it also is very educational and makes me want to do more prevention care and more education.”

Behavior Change Reflection and Intentions

Viewers were moved to consider personal wellness changes by watching the digital stories, as reported in their verbal and written comments. Digital stories connected with people at both a heart and head place of knowing which initiated personal reflections.

“These little stories really make you think about your own life, could be life changing in a good way. The stories really bring up emotions with information.”

Additionally, digital stories served as a stimulus for wellness conversations as well as a reported commitment to wellness activities. Digital stories helped to shape viewers’ behavioral intentions.

“The stories really connect to me because of the emotions, feelings. The story makes me more resolved. I’ve got to quit smoking.”

A new door opened with digital stories. Encouraged me more to get screening—I’ve had a tough time getting a colonoscopy and now I’ll make an appointment this week. Watching those little stories helped me make that decision.”

Discussion

Digital storytelling offers an array of health promotion possibilities. Focus group participants liked digital stories so much that they wanted to make their own, offered ways to increase exposure, and felt that digital stories were so compelling that they should be seen by everyone in their community. Participants expressed a desire to share information with the youth in their communities and thought that this digital storytelling approach would resonate with younger people as well as people their age. Digital stories have been used successfully on other topics; in Northwest Alaska, young people have eagerly created digital stories to highlight positive aspects of their lives [26].

Digital stories also appeared to communicate with people across regions and cultures because it connected with people at an emotional level of understanding that speaks to the shared human experience. Digital stories entered the silence that often surrounds cancer, serving as an opening for challenging conversations. The viewing of digital stories prompted the telling of viewer stories, which added to viewers’ knowledge and understanding. Due to the personal nature of digital stories, they powerfully connected with viewers both cognitively and affectively, linking realms of wisdom. Viewers reported an increase in cancer knowledge and understanding, which served as a motivator for wellness behavioral change.

Future Directions

Digital storytelling is a powerful way for community health workers to tell and share their stories to promote community health. CHWs may enhance their stories by focusing on the elements of an engaging and motivating story that have been described in this article. To add to the understanding of how digital stories are used as a cancer-related health messaging tool, it will be helpful to learn how story creators share their digital stories and what effect digital stories have on viewers over time.

Figure 1.

Map Showing focus group locations

Acknowledgments

The Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium received support from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21CA163163 in September 2013. The award funded research to increase understanding of digital storytelling as a culturally respectful and meaningful way for Alaska’s village-based community health workers (CHWs) to create and share cancer prevention and screening messages with Alaska’s communities. Co-funding for this 2-year award was provided by the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences and from the Office of Disease Prevention. Thank you to Alaska’s community health workers who created their personal cancer-related digital story as a powerful health messaging tool.

Footnotes

Research reported in this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Melany Cueva, Email: mcueva@anthc.org.

Regina Kuhnley, Email: ckuhnley@anthc.org.

Laura Revels, Email: ljrevels@anthc.org.

Nancy E. Schoenberg, Email: nesch@uky.edu.

Anne Lanier, Email: aplanier@anthc.org.

Mark Dignan, Email: mbdign2@email.uky.edu.

References

- 1.Lanier A, Hollck P, Kelly J, Smith B, McEvoy T. Alaska Native cancer survival. Alaska Med. 2001;43(3):61–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly J, Schade T, Starkey M, Ashokkumar R, Lanier AP. Cancer in Alaska Native People 1969–2008 40-year report. Alaska Native Tumor Registry Alaska Native Epidemiology Center Division of Community Health Services Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium; Anchorage. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Preventive Services Task Force. [Accessed 15 Dec 2014]; http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/BrowseRec/Index/browse-recommendations.

- 4.American Institute of Cancer Research. [Accessed 16 Dec 2014]; http://www.aicr.org/reduce-your-cancer-risk/recommendations-for-cancer-prevention.

- 5.Mayo W Natives of Alaska. Alaska Native ways: what the elders have taught us. Graphic Arts Center; Portland: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodge FS, Pasqua A, Marquez CA, Geishirt-Cantrell B. Utilizing traditional storytelling to promote wellness in American Indian communities. J Transcult Nurs. 2002;13(1):6–11. 7. doi: 10.1177/104365960201300102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cueva M, Kuhnley R, Lanier A, Dignan M. Story: the heartbeat of learning. Convergence. 2007;39(4):81–88. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kreuter M, Wray R. Tailored and targeted health communication: strategies for enhancing information relevance. J Health Behav. 2003;27(suppl):227–232. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.1.s3.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kreuter M, McClure S. The role of culture in health communication. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:439–455. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreuter M, Buskirk T, Holmes K, et al. What makes cancer survivors stories work? An empirical study among African American women. J Cancer Survivorship. 2008;2:33–44. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0041-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cueva M, Kuhnley R, Revels L, Cueva K, Dignan M, Lanier A. Bridging storytelling traditions with digital technology. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2013;72(20717):270–275. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.20717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambert J Center for digital storytelling. [Accessed 12 Nov 2014]; www.storycenter.org.

- 13.Lambert J. Digital storytelling capturing lives, creating community. Digital Diner, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kajder S, Bull G, Albaugh S. Constructing digital stories. Learn Lead Technol. 2005;32(5):40–42. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oppermann M. Digital storytelling and American studies: critical trajectories from the emotional to the epistemological. Arts Humanit High Educ: Int J Theory Res Pract. 2008;7(2):171–187. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandars J, Murray C. Digital storytelling for reflection in undergraduate medical education: a pilot study. Educ Prim Care. 2009;20:441–444. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2009.11493832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandars J, Murray C, Pellow A. Twelve tips for using digital storytelling to promote reflective learning. Med Teach. 2008;30:774–777. doi: 10.1080/01421590801987370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barrett H. [Accessed 11 Dec 2014];Researching and evaluating digital storytelling as a deep learning tool. 2005 http://electronicportfolios.com/portfolios/SITEStorytelling2006.pdf.

- 19.McLellan H. Digital storytelling in higher education. J Comput High Educ. 2006;19(1):65–79. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benmayor R. Digital storytelling as a signature pedagogy for the new humanities. Arts Humanit High Educ: Int J Theory Res Pract. 2008;7(2):188–204. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cumming GP, Currie HD, Moncur R, Lee AJ. Web-based survey on the effect of digital storytelling on empowering women to seek help for urogenital atrophy. Menopause Int. 2010;16(2):51–55. doi: 10.1258/mi.2010.010004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dewey J. Art as experience. Perigree Books; New York: 1934. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denzin N, Lincoln Y, Tuhiwai-Smith L. Handbook of critical and indigenous methodologies. Sage, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tuhiwai Smith L. Decolonozing methodologies: research and indigenous peoples. University of Otago Press; Dunedin: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Denzin L, Lincoln Y. Handbook of qualitative research. Sage, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wexler L, Gubrium A, Griffin M, DiFulvio G. Promoting positive youth development and highlighting reasons for living in northwest Alaska through digital storytelling. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14(4):617–623. doi: 10.1177/1524839912462390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]