Abstract

The management of benign papilloma (BP) without atypia identified on breast core needle biopsy (CNB) is controversial. We describe the clinicopathologic features of 80 patients with such lesions in our institution, with an upgrade rate to malignancy of 3.8%. A multidisciplinary approach to select patients for surgical excision is recommended.

Background

The management of benign papilloma (BP) without atypia identified on breast core needle biopsy (CNB) is controversial. In this study, we determined the upgrade rate to malignancy for BPs without atypia diagnosed on CNB and whether there are factors associated with upgrade.

Methods

Through our pathology database search, we studied 80 BPs without atypia identified on CNB from 80 patients from 1997 to 2010, including 30 lesions that had undergone excision and 50 lesions that had undergone ≥ 2 years of radiologic follow-up. Associations between surgery or upgrade to malignancy and clinical, radiologic, and pathologic features were analyzed.

Results

Mass lesions, lesions sampled by ultrasound-guided CNB, and palpable lesions were associated with surgical excision. All 3 upgraded cases were mass lesions sampled by ultrasound-guided CNB. None of the lesions with radiologic follow-up only were upgraded to malignancy. The overall upgrade rate was 3.8%. None of the clinical, radiologic, or histologic features were predictive of upgrade.

Conclusion

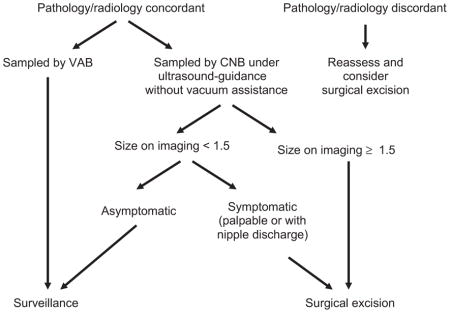

Because the majority of patients can be safely managed with radiologic surveillance, a selective approach for surgical excision is recommended. Our proposed criteria for excision include pathologic/radiologic discordance or sampling by ultrasound-guided CNB without vacuum assistance when the patient is symptomatic or lesion size is ≥ 1.5 cm.

Keywords: Breast, Core needle biopsy, Criteria, Papilloma, Upgrade

Introduction

Papillary lesions of the breast are uncommon. The incidence in core needle biopsy (CNB) specimens of the breast is reportedly up to 6%.1–3 Histologically, they include intraductal papillary lesions (intraductal papilloma, intraductal papillary carcinoma, encapsulated papillary carcinoma, and solid papillary carcinoma) and invasive papillary carcinoma.4 Clinically, papillary lesions may present with nipple discharge or as a palpable mass, or both. They may be located centrally or peripherally in the breast parenchyma and may be solitary or multiple. With widespread breast cancer screening programs, the majority of these papillary lesions are now being detected by ultrasonography or mammography as asymptomatic masses or calcifications. There are no specific radiologic features differentiating a benign papilloma from its atypical or malignant counterparts.5,6

To date, there is substantial evidence that a diagnosis of atypical intraductal papilloma on CNB requires surgical excision because of a significant risk of associated carcinoma (ductal carcinoma in situ [DCIS] and/or invasive carcinoma [IC]).1,7–15 However, debate continues on the appropriate management of a benign papilloma (BP) without atypia diagnosed on CNB. Some authors believe that BPs without atypia can be managed safely with clinical and radiologic follow-up if the radiologic and pathologic findings are concordant,10,11,16–24 whereas others recommend excision for this group of patients to rule out any associated malignancy.6,25–42 Reasons for excision stem from the inherent sampling issues of CNB and potential heterogeneity in the distribution of atypia or carcinoma, if present, within a papillary lesion. In addition, the fact that papillary lesions can be diagnostically challenging, especially on CNB, may prompt some to recommend excision.9 In published studies, the upgrade rate to carcinoma with a diagnosis of BP without atypia on CNB ranges from 0% to 29%.1–3,6,10–57 We present here our institution’s experience with BP without atypia diagnosed on CNB and propose criteria for surgical excision.

Materials and Methods

Case Selection

Our pathology database was searched using keywords for all cases of papilloma of the breast diagnosed on CNB specimens from January 1997 to December 2010. Medical records and histologic slides were reviewed. Exclusion criteria included (1) nonavailability of the CNB material for review, (2) concurrent diagnosis of DCIS or IC in the ipsilateral breast, (3) presence of any atypia within the papilloma or atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) outside the papilloma in the same CNB specimen, (4) incidental papillomas such as microscopic papillomas not associated with microcalcifications if the CNB was performed for suspicious calcifications, or (5) clinical and radiologic follow-up < 2 years if excision was not performed. The resulting 80 lesions from 80 patients were the subjects of this study, including 30 lesions found on CNB with corresponding surgical excision specimens and 50 cases with a minimum of 2 years of radiologic follow-up. Eighteen cases published in an earlier study from our institution16 fulfilled the selection criteria and were included. This project was approved by the Institutional Review Board of MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Radiologic, Pathologic, and Clinical Features

Ultrasound-guided biopsies were performed using 12-, 14-, 16-, or 18-gauge automated Bard Core Disposable Needles (C.R. Bard, Covington, GA). Stereotactic and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-guided biopsies were performed using a 9-gauge vacuum-assisted Suros ATEC breast biopsy device (Suros Surgical systems/ Hologic, Indianapolis, IN). A metallic marker clip was placed at the biopsy site. For stereotactic biopsies, a postprocedural radiograph of tissue cores was obtained to ensure adequate sampling of calcifications.

Radiologic features of the lesions were reevaluated retrospectively by an experienced breast radiologist (SC). Features evaluated for all lesions included lesion size, number, location (retroareolar, central, or peripheral), and Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) scores according to the American College of Radiology. In addition, features evaluated for mass lesions included shape (oval/ round, lobular, irregular), margins (circumscribed, not circumscribed), echo pattern (isoechoic, hypoechoic, hyperechoic, mixed or complex cystic), associated dilatated duct (present, absent), mammographic correlate (present, absent), and degree of sampling (whether the lesion was entirely removed by CNB). Features evaluated for lesions with suspicious calcifications included their type (pleomorphic, amorphous, coarse/heterogeneous, punctate, fine linear branching) and distribution (clustered/grouped, linear, segmental, regional), ultrasonographic correlate (present, absent), and percentage of calcifications remaining after the biopsy procedure. For lesions identified on MRI and lesions with calcification-associated masses or asymmetry, the features described earlier for mass lesions and calcifications were evaluated when appropriate. Biopsy approach, needle gauge, and number of cores obtained were recorded for each lesion. To assess the stability of papillary lesions without atypia diagnosed on CNB, a short-term radiologic follow-up (6 months) was performed in our institution for > 2 years using the imaging modality by which the lesion was detected (mammography and/or ultrasonography and MRI). A lesion with no change at 2 years was considered benign, and return to annual follow-up was recommended.

Hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides of the CNB specimens were reviewed independently by 2 breast pathologists (AN and LH) to confirm the diagnosis of BP without atypia. The number of cores involved by papilloma and the presence of apocrine metaplasia within the papilloma were recorded. The diagnoses rendered for the excision specimens, when applicable, were extracted from the pathology reports. Upgrade to malignancy was defined as DCIS or IC identified at excision. Histologic slides of excision specimens, including all 3 upgraded cases, were reviewed whenever available.

Medical records were reviewed for patient age, menopausal status, personal or family history of breast cancer, palpable lesion, associated nipple discharge (including type of discharge—bloody or clear), and radiologic follow-up data.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical tests were performed using SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC) and R, version 2.15.1 (R Core Team; http://www.R-project.org). For analyzing the correlation between 2 categorical variables, the Fisher exact test was used. For analysis of continuous variables, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used. A P value of < .05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

All 80 eligible patients were women between the ages of 31 and 81 years (median, 52 years; mean, 53 years). Thirty patients underwent subsequent excision and the remaining 50 patients had radiologic follow-up of ≥2 years (range, 24–150 months; median, 50 months; mean, 58 months). Clinical and radiologic characteristics of the 80 cases are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of Clinical and Radiologic Features in Excised and Not Excised Cases

| Variablea | Excised (n = 30) | Not Excised (n = 50) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Variables | |||

| Age range, years (median) | 31–74 (51) | 38–81 (53) | .214 |

| Menopause status (n = 74) | .298 | ||

| Premenopausal | 11 | 11 | |

| Postmenopausal | 18 | 34 | |

| Family history of breast cancer (n = 77) | .633 | ||

| Yes | 13 | 18 | |

| No | 16 | 30 | |

| Previous history of breast cancer | .098 | ||

| Yes | 10 | 8 | |

| No | 20 | 42 | |

| Nipple dischargeb | 1.000 | ||

| Yes (type) | 4 (2B, 1C, 1U) | 6 (2B, 3C, 1U) | |

| No | 26 | 44 | |

| Palpable | < .0001 | ||

| Yes | 12 | 2 | |

| No | 18 | 48 | |

| Radiologic Variables | |||

| Radiologic appearancec | < .0001 | ||

| Mass | 26 | 18 | |

| Calcifications or enhancement | 4 | 32 | |

| Multiplicity of lesions | .120 | ||

| < 3 | 23 | 45 | |

| Multiple (≥ 3) | 7 | 5 | |

| Location | .464 | ||

| Peripheral | 22 | 32 | |

| Central/retroareolar | 8 | 18 | |

| BI-RADS category | .216 | ||

| 3 | 4 | 3 | |

| 4 | 25 | 47 | |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | |

| Mode of biopsy | < .0001 | ||

| Ultrasound-guided | 25 | 16 | |

| Stereotactic or MRI-guided | 5 | 34 |

Abbreviations: B = bloody; BI-RADS = Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System; C = clear; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; U = unknown.

For all variables, n = 80 unless indicated otherwise.

The type of nipple discharge is not significant (n = 8; P = 1; not shown in Table 1).

All mass lesions and calcifications with an associated mass or asymmetry biopsied under ultrasound-guidance are included in “Mass”; all calcifications, calcifications with an associated mass or asymmetry biopsied by a stereotactic approach, and lesions identified on MRI are included in “Calcifications or enhancement.”

Radiologically, 40 lesions were masses detected by ultrasonography, 28 were calcifications identified by mammography, 10 were calcifications with an associated mass or asymmetry identified by mammography with or without ultrasonography, and 2 were clumped enhancement or masses detected by MRI. Thirty-seven patients with mass lesions and 4 patients with calcifications with an associated mass or asymmetry underwent ultrasound-guided CNB. Twenty-eight patients with calcifications, 6 patients with calcifications with an associated mass or asymmetry, and 3 patients with mass lesions underwent stereotactic biopsy. The 2 patients with clumped enhancement or masses detected by MRI underwent MRI-guided biopsy.

As shown in Table 1, mass lesions, lesions sampled by ultrasound-guided CNB, and palpable lesions were associated with surgical excision. At the time of CNB, 18 patients had a history of IC or DCIS, including 14 contralateral and 4 ipsilateral cases. The intervals between the excision of the previous carcinoma and the CNB for papilloma in the 4 ipsilateral cases were 3 months for 1 and 6 to 17 years for the other 3.

Among patients with ultrasound-guided CNB, the only clinical or radiologic variable associated with excision was the presence of a palpable lesion (Table 2). None of the clinical or radiologic variables was associated with excision in patients who underwent stereotactic or MRI-guided biopsy (Table 3).

Table 2.

Comparison of Clinical and Radiologic Features of Mass Lesionsa in Excised And Not Excised Cases

| Variableb | Excised (n = 26) | Not Excised (n = 18) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Palpable | .006 | ||

| Yes | 12 | 1 | |

| No | 14 | 17 | |

| Size in cm (median) (n = 43) | 0.6–3.2 (1.2) | 0.4–2.4 (1.0) | .353 |

| Multiplicity of lesion | .211 | ||

| < 3 | 20 | 17 | |

| Multiple (≥3) | 6 | 1 | |

| Location | .525 | ||

| Peripheral | 18 | 10 | |

| Central/retroareolar | 8 | 8 | |

| Shape (n = 41) | .487 | ||

| Oval-round | 11 | 5 | |

| Lobular | 5 | 6 | |

| Irregular | 8 | 6 | |

| Margins (n = 42) | 1.000 | ||

| Circumscribed | 10 | 7 | |

| Not circumscribed | 15 | 10 | |

| Echo Pattern (n = 42) | .066 | ||

| Isoechoic/hypoechoic | 19 | 17 | |

| Complex cystic | 6 | 0 | |

| Associated Dilated Duct (n = 42) | |||

| Yes | 8 | 4 | .731 |

| No | 17 | 13 | |

| Mammographic Correlate | |||

| Yes | 19 | 8 | .068 |

| No | 7 | 10 | |

| BI-RADS Category | |||

| 3 | 4 | 3 | 1.000 |

| 4 | 22 | 15 | |

| Number of Cores Sampled (median) | 3–12 (4) | 2–13 (4) | .759 |

Abbreviation: BI-RAD = Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System.

This group includes all mass lesions and calcifications with an associated mass or asymmetry biopsied under ultrasound-guidance.

For all variables, n = 44 unless indicated otherwise.

Table 3.

Comparison of Radiologic Features of Calcifications and Enhancementa in Excised and Not Excised Cases

| Variablesb | Excised (n = 4) | Not Excised (n = 32) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size in cm (median) (n = 32) | 0.2–4 (0.75) | 0.2–2.2 (0.65) | .841 |

| Multiplicity of Lesion | .466 | ||

| < 3 | 3 | 28 | |

| Multiple (≥ 3) | 1 | 4 | |

| Location | .559 | ||

| Peripheral | 4 | 22 | |

| Central/retroareolar | 0 | 10 | |

| Type of Calcifications (n = 31) | .232 | ||

| Amorphous/punctuate | 3 | 14 | |

| Heterogeneous/linear/pleomorphic | 0 | 14 | |

| Distribution of Calcifications (n = 33) | .256 | ||

| Clustered/linear | 2 | 28 | |

| Segmental/regional | 1 | 2 | |

| Ultrasonographic correlate (n = 12) | 1.000 | ||

| Yes | 0 | 1 | |

| No | 1 | 10 | |

| Calcifications Remaining After Biopsy (n = 24) | .590 | ||

| Yes | 3 | 9 | |

| No | 1 | 11 | |

| Number of Cores Sampled (median) | 3–14 (8.5) | 4–17 (9.0) | .595 |

This group includes calcifications, calcifications with an associated mass or asymmetry biopsied by a stereotactic approach, and lesions identified on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

For all variables, n = 36 unless indicated otherwise.

The reason for excision was not known for every patient. Fifteen patients who underwent excision had a palpable mass and/or nipple discharge. Eleven of the 80 cases were discussed at breast multi-disciplinary management conferences held weekly since 2004. Excision was recommended in 3 of these 11 cases because of the small and fragmented nature of the CNB specimen in 2 patients and a clinical history of increase in lesion size in 1 patient. Three cases that were upgraded to DCIS were not presented at the conference but had specific reasons for excision, as described further on. Seven lesions with a BI-RADS score of 3 were biopsied, including 4 excised because of an increase in size during radiologic follow-up or because of the patient’s or surgeon’s preference. The only BI-RADS 5 lesion was excised and showed benign pathologic characteristics. Surgical excision was performed within 6 months of the CNB diagnosis in 26 of 30 patients. The remaining 4 lesions, including 1 case upgraded to DCIS on excision, were excised 9 to 25 months later on detection of a clinical or imaging abnormality during follow-up.

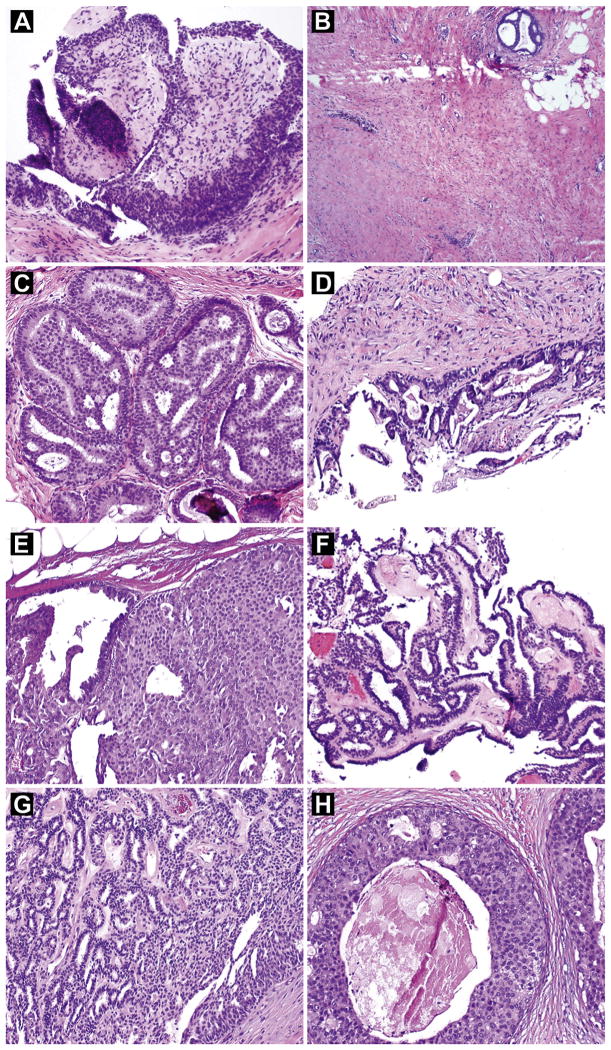

Three of the 30 cases were upgraded to carcinoma in the excised subgroup. Although all 3 presented with mass lesions identified and biopsied by ultrasonography, the presence of a mass lesion (vs. calcifications) was not significantly associated with upgrade (P = .25). Among the 3 patients, 1 patient had a concurrent diagnosis of DCIS in the contralateral breast and a concurrent diagnosis of ADH in the ipsilateral breast in a separate CNB specimen. The biopsied areas with ADH and papilloma were approximately 2 cm apart. The papilloma was a 0.7-cm oval hypoechoic mass lesion biopsied with a 14-gauge needle (Fig. 1A). The patient had clear nipple discharge. In the total mastectomy specimen, low-grade DCIS was identified in a 1-cm area around the biopsy site of the papilloma and farther away from the biopsy site showed ADH. No residual papilloma remained at the biopsy site (Fig. 1B and C). The second patient presented with a palpable lesion, corresponding to a 1.5-cm solid hypovascular mass biopsied with an 18-gauge needle, which yielded small pieces of fragmented tissue with a portion of a cyst wall and a focal epithelial lesion consistent with a papilloma (Fig. 1D). Because of inadequate sampling, an excisional biopsy was performed, which revealed 0.4 cm intermediate-grade DCIS involving an infarcted papilloma (Fig. 1E). The third patient had a remote history of contralateral breast cancer. She presented with a palpable periar-eolar mass that had a complex cystic appearance on ultrasonography and measured 1.6 cm. A CNB specimen obtained with a 14-gauge needle showed a papilloma (Fig. 1F). Excision was not performed at the time and the patient was followed radiologically every 6 months for a year and then annually. Two years after the initial biopsy for the papilloma, she was found to have a hypoechoic ill-defined area on ultrasonography that was almost contiguous with the previous papilloma. A CNB showed DCIS. A total mastectomy revealed a 1.9-cm area of high-grade DCIS immediately adjacent to the papilloma (Fig. 1G and H). Although it was unclear whether the DCIS was already present at the time of the CNB for the papilloma, because of their close proximity this case was considered as an upgrade. Although invasive tumor was not identified in the breast specimen, a micrometastasis of 0.22 mm was identified in an axillary sentinel lymph node.

Figure 1.

Hematoxylin and Eosin Stains of Biopsy and Excision Specimens of the 3 Papilloma Cases Upgraded to Malignancy. (A–C) First Case. (A) Biopsy Specimen Showing a Papilloma. (B) No Residual Papilloma at the Biopsy Site on Excision. (C) Ductal Carcinoma in Situ (DCIS) Surrounding the Biopsy Site on Excision. (D and E) Second Case. (D) Biopsy Specimen Showing a Papilloma. (E) DCIS Involving Papilloma on Excision (Right Side). (F–H) Third Case. (F) Biopsy Specimen Showing a Papilloma. (G) Papilloma on Excision, Showing no Atypia. (H) DCIS Surrounding Papilloma on Excision. (Original Magnification: A, C–H, ×100; B, ×40.)

Nine of the remaining 27 excised cases demonstrated ADH on excision. The ADH was within the papilloma in 3 cases, outside the papilloma in 3 cases, and both within and outside the papilloma in 3 cases. The other excised cases showed BPs without atypia in 17 cases and fibrocystic changes in 1 case.

Among the 50 patients who had follow-up without excision, ipsilateral low-grade metaplastic carcinoma developed in 1 patient 54 months after the initial biopsy for a 0.7-cm papilloma. The area of the papilloma was distinct from the carcinoma and was stable on imaging but was not sampled in the excision specimen. Therefore, this case was considered as if it had follow-up only without excision. The remaining 49 patients showed no evidence of malignancy on follow-up.

The overall upgrade rate to malignancy in this cohort was 3.8% (3 of 80 cases). None of the clinical, radiologic, or histologic features were predictive of upgrade in the entire cohort, in the excised group, in the group with mass lesions, or in the excised mass lesion group (P > .05). Selected clinical and radiologic features of the upgraded and not upgraded cases within the mass lesion group are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of Clinical and Radiologic Features of Mass Lesionsa in Cases With and Without Upgrade to Malignancy

| Variablesb | Upgrade (n = 3) | No Upgrade (n = 41) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age range (median) | 47–62 (56) | 31–74 (50) | .428 |

| Previous History of Breast Cancer | .125 | ||

| Yes | 2 | 8 | |

| No | 1 | 33 | |

| Palpable Mass | .204 | ||

| Yes | 2 | 11 | |

| No | 1 | 30 | |

| Size in cm (median) (n = 43) | 0.7–1.6 (1.5) | 0.4–3.2 (1) | .774 |

| Multiplicity of Lesion | 1.000 | ||

| < 3 | 3 | 34 | |

| Multiple (≥3) | 0 | 7 | |

| Location | 1.000 | ||

| Peripheral | 2 | 26 | |

| Central/retroareolar | 1 | 15 | |

| Mammographic correlate | .550 | ||

| Yes | 1 | 26 | |

| No | 2 | 15 | |

| BI-RADS | 1.000 | ||

| 3 | 0 | 7 | |

| 4 | 3 | 34 | |

| Number of Cores Sampled (median) | 4–5 (4) | 2–13 (4) | .940 |

| Number of Cores Involved by Papilloma (median) (n = 37) | 1–4 (1) (n = 3) | 1–9 (3) (n = 34) | .264 |

| Apocrine Metaplasia in Papilloma on Core Biopsy Specimen (n = 37) | 1.000 | ||

| Yes | 1 | 11 | |

| No | 2 | 23 |

Abbreviation: BI-RAD = Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System.

This group includes all mass lesions and calcifications with an associated mass or asymmetry biopsied under ultrasound-guidance.

For all variables, n = 44 unless indicated otherwise.

Discussion

Although excision of BP with atypia is generally recommended, the clinical management of BPs without atypia diagnosed on CNB is controversial. Studies in the past have yielded divergent results on the actual risk of upgrade to malignancy after a CNB diagnosis of BP without atypia. One apparent factor to contribute to the difference in the literature lies in the variable exclusion criteria, which makes it difficult to compare all the studies. Nonetheless, as shown in Table 5, the reported upgrade rate ranges from 0% to 29%. More than 10 studies found a 0% upgrade rate,1,10,11,16–18,20–24,44,46,47 although most had a relatively small number of lesions. The series with > 100 BPs without atypia, in which most of the lesions were surgically excised, demonstrated a range of upgrade rate of 5% to 12%.3,28,30,34,35,39,41,54,56,57 Although the majority of the studies were retrospective, 3 were prospective.22,25,52 One of these studies showed an upgrade rate of 6.5% in 31 surgically excised BPs without atypia. The authors recommended surgical excision.25 In that study, all but 2 of the cases were sampled by a 14-gauge automated biopsy needle. Another prospective study included 100 BPs without atypia identified by 14-gauge ultrasound-guided biopsy. On excision, 4 were upgraded to malignancy.52 Because the mean lesion size on imaging in this study was significantly associated with upgrade, the authors recommended considering excision in BPs without atypia that are > 1.5 cm. The third prospective study of 49 BPs without atypia concluded that surgical excision may not be required after ultrasound-guided 11-gauge vacuum-assisted biopsy (VAB).22 In their series, none of the lesions was upgraded to malignancy on excision. The overall upgrade rate in our retrospective study was 3.8%, which is within the reported range but toward the lower end of the spectrum. In our study, we defined upgrade as finding DCIS or invasion at surgical excision. Although the presence of atypia such as ADH or atypical lobular hyperplasia at excision may prompt the consideration of chemoprevention, the significance of such findings on reducing the mortality and morbidity of patients is not clear enough to warrant excision.

Table 5.

Summary of Reported Studies on Malignant Upgrade of Benign Papillomas Without Atypia Diagnosed on Core Needle Biopsy

| Reference | Biopsy Approach | Total Number of Lesions | Number of Surgically Excised Lesions | Number of Upgrade (%) | Recommend Excision in All Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberman et al, 19991 | AN, VAB | 7 | 4 | 0 | No |

| Philpotts et al, 200043 | AN, VAB | 16 | 6 | 1 (6.3) | No |

| Mercado et al, 20012 | VAB | 12 | 6 | 1 (8.3) | No |

| Irfan and Brem, 200244 | VAB | 6 | 3 | 0 | NA |

| Rosen et al, 200210 | AN, VAB | 33 | 4 | 0 | No |

| Ivan et al, 200416 | AN, VAB | 30 | 6 | 0 | No |

| Puglisi et al, 200325 | AN | 31 | 31 | 2 (6.5) | Yes |

| Renshaw et al, 200417 | AN, VAB | 18 | 18 | 0 | No |

| Agoff and Lawton, 200411 | AN, VAB | 16 | 11 | 0 | No |

| Carder et al, 200518 | AN, VAB | 17 | 16 | 0 | No |

| Liberman et al, 200626 | AN, VAB | 35 | 25 | 5 (14) | Yes |

| Mercado et al, 200627 | AN, VAB | 43 | 36 | 2 (4.7) | Yes |

| Shah et al, 200645 | NA | 35 | 35 | 1 (2.9) | No |

| Sydnor, et al, 200712 | AN, VAB | 48 | 23 | 3 (6.3) | No |

| Ashkenazi et al, 200713 | AN, VAB | 10 | 10 | 0 | No |

| Ko et al, 200714 | AN | 43 | 19 | 1 (2.3) | No |

| Sohn et al, 200719 | AN, VAB | 174 | 0 | 2 (1.1) | No |

| Arora et al, 200746 | AN, VAB | 18 | 18 | 0 | No |

| Shin et al, 200828 | AN, VAB | 101 | 86 | 12 (12) | Yes |

| Skandarajah et al, 200829 | AN, VAB | 80 | 80 | 15 (19) | Yes |

| Sakr et al, 200833 | AN, VAB | 48 | 48 | 4 (8.3) | Yes |

| Kil et al, 200815 | AN, VAB | 68 | 68 | 6 (8.8) | No |

| Carder et al, 200847 | AN | 26 | 11 | 1 (3.8) | No |

| Zografos et al, 200820 | VAB | 40 | 40 | 0 | No |

| Rizzo et al, 200830 | VAB | 101 | 101 | 9 (8.9) | Yes |

| El-Sayed et al, 200848 | NA | 99 | 99 | 4 (4) | No |

| Tseng et al, 200931 | AN | 24 | 24 | 7 (29) | Yes |

| Bernik et al, 200932 | AN, VAB | 47 | 47 | 4 (8.5) | Yes |

| Bode et al, 20096 | AN | 23 | 23 | 2 (8.7) | Yes |

| Cheng et al, 200949 | NA | 77 | 77 | 3 (3.9) | Yes |

| Ahmadiyeh et al, 200950 | Mammography, US, MRI guidance | 71 | 29 | 1 (1.4) | No |

| Jaffer et al, 200934 | AN, VAB | 104 | 104 | 9 (8.7) | Yes |

| Maxwell, 200951 | VAB | 26 | 3 | 0 | No |

| Chang et al, 201052 | AN | 100 | 100 | 4 (4) | No |

| Jung et al, 201035 | AN | 160 | 160 | 10 (6.3) | Yes |

| Bennett et al, 201021 | AN, VAB | 120 | 45 | 0 | No |

| Tse et al, 201053 | NA | 68 | 68 | 7 (10) | Yes |

| Youk et al, 201154 | AN | 160 | 160 | 8 (5) | NA |

| Cyr et al, 201136 | AN, VAB | 193 | 84 | 10 (5.2) | Yes |

| Chang et al, 201137 | AN, VAB | 64 | 64 | 2 (3.1) | Yes |

| Chang et al, 201122 | VAB | 49 | 49 | 0 | No |

| Kim et al, 20113 | AN, VAB | 211 | 136 | 12 (5.7) | No |

| Richter-Ehrenstein et al, 201155 | AN, VAB | 64 | 45 | 2 (4.4) | No |

| Rozentsvayg et al, 201138 | AN, VAB | 67 | 67 | 5 (7.5) | Yes |

| Rizzo et al, 201239 | NA | 234 | 234 | 21 (8.9) | Yes |

| Shouhed et al, 201240 | VAB | 59 | 59 | 6 (10) | Yes |

| Holley et al, 201256 | AN, VAB | 128 | 86 | 14 (11) | No |

| Fu et al, 201241 | Needle | 203 | 203 | 12 (5.9) | Yes |

| Brennan et al, 201242 | VAB (MRI) | 44 | 44 | 2 (5) | Yes |

| Li et al, 201257 | Mammography, US, MRI guidance | 370 | 370 | 7 (1.9) | No |

| Swapp et al, 201323 | US, MRI | 177 | 77 | 0 | No |

| Sohn and Park, 201324 | Needle | 39 | 34 | 0 | No |

| Total | 4037 | 3196 | 217 (5.4) |

Abbreviations: AN = automated needle; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; NA = not available; US = ultrasonography; VAB = vacuum-assisted biopsy.

Several studies have attempted to correlate clinical, imaging, and histologic features of papillomas with malignancy on excision. Some of these identified older age, postmenopausal status, mixed hyper-echoic/hypoechoic or complex cystic echo pattern and non-circumscribed margin on imaging, peripheral location, larger lesion size, nipple discharge, and microcalcifications among the factors associated with malignancy.3,12,15,22,28,33,39,42,50 However, having included atypical papillomas in the study cohorts when making such correlations, they could not effectively identify predictors of upgrade within the BPs without atypia group. Only a few studies evaluated BPs without atypia separately.26,34,35,37,40,52,54,56,57 Although some failed to find any factors associated with upgrade on excision,26,34,41 others showed that larger lesion size (cutoffs, 1–1.5 cm),37,52,54 palpable lesion,35,40 mass,35,56 biopsy by non-VAB approach,56 older age (cutoff, 50 years), peripheral lesion, higher BI-RADS score, and pathologic/imaging discordance54 were associated with upgrade. One study that included largely BPs without atypia that were identified on ultrasound-guided CNB found that the presence of microcalcifications on histologic slides of the CNB specimens was associated with upgrade to malignancy.57 In our series, we did not find any clinical, radiologic, or histologic variable that could reliably predict malignancy on excision. All of the 3 lesions with upgrade were mass lesions. One had inadequate sampling on CNB, 1 had a separate but adjacent area of ADH identified on a different CNB specimen, and the third had new findings on radiologic follow-up immediately adjacent to the papilloma, prompting further intervention.

Defined criteria were not clear as to whether surgical excision or radiologic follow-up was appropriate in all the patients in our cohort. A few factors were associated with the decision to perform surgical excision in our study. The presence of a palpable or mass lesion and an ultrasound-guided CNB approach were each associated with surgical excision (Table 1). The last 2 factors were most likely related, because the biopsy approach was largely dependent on whether a mass lesion was present. In the mass lesion group, the presence of a palpable lesion remained associated with excision (Table 2). Our results share some similarities with 1 previous report, which showed that the radiographic type of lesion (micro-calcifications) and the biopsy approach (stereotactic) were associated with the decision not to excise.36 Two other studies failed to find any associations with excision.30,50

Renshaw et al. pointed out that the incidence of carcinoma at excision associated with a diagnosis of BP without atypia is related to sampling rather than to any increased risk pertaining to the diagnosis itself.17 Others have also emphasized the role of sampling in this context.8,9 The development of directional VAB devices in the mid-1990s, now usually coupled with 9-gauge or 11-gauge needles, provides an approach to harvest a larger volume of tissue than is possible with the automated large-core biopsy device commonly equipped with a 14-gauge needle. Although 1 earlier study did not find any association between the biopsy approach and upgrade to malignancy on excision of BP without atypia,26 some series showed no upgrade when BPs without atypia were diagnosed by VAB, in contrast to those biopsied by automated needle.15,37 Similarly, in our study, all 3 lesions upgraded to malignancy were biopsied using automated needles. However, the difference did not reach statistical significance in either of these reported studies of BPs without atypia or in ours. Several studies that focused on BP without atypia identified by VAB, including 1 recent prospective study and 1 study on lesions identified by MRI, demonstrated a combined overall upgrade rate of 5.3% (18 of 337 BPs without atypia, including 305 that underwent excision and 32 with follow-up).2,20,22,30,40,42,44,51 Of note, this is similar to the upgrade rate of 5.4% when all the studies are considered (Table 5). Although data on VAB of BP without atypia are limited, some authors have suggested that those diagnosed by large-needle VAB may not need excision.22,51,58 VAB has also gained recognition lately as an approach to manage patients after BPs without atypia are diagnosed on automated needle biopsy specimens, hence sparing a subset of patients from surgery.47,54,59–62 Experience is still accumulating in this regard.

Retrospective in nature, our study has its limitations. The number of cases is small. As stated earlier, our exclusion criteria limited the study to a group of 80 patients. Of note, we required histologic review of the CNB material in all cases and eliminated incidental papillomas. Selection bias could have masked the true upgrade rate. The fact that not all patients underwent excision is also a limitation, although the follow-up time in the patients who did not undergo excision was relatively long (mean, 58 months). We could not discern the reasons for excision vs. radiologic follow-up in all cases, and unknown bias for excision cannot be excluded. It may be reasonable to postulate that the true upgrade rate of our cohort is between 3.8% (3 of 80 cases) and 10% (3 of 30 excised cases), although one would hope that the number is closer to the former after carefully selecting patients for excision.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the upgrade rate for BPs without atypia diagnosed on CNB was 3.8% in our series, and there were no clinical, radiologic, or histologic features predictive of upgrade. Although there appears to be a small risk of upgrading to malignancy based on our experience as well as that of others, we are cautious in recommending excision of all BPs without atypia because the majority of patients can be safely followed by radiologic surveillance. Patients who undergo CNB with adequate sampling and good radiologic/ pathologic correlation, especially those who undergo VAB, may be candidates for conservative management. Based on our experience and careful review of the literature, we propose the following approach for selecting patients for surgical excision:

When the preceding approach is applied to our study cohort, 24 patients would undergo surgical excision, including 16 of the 30 patients who underwent excision and 8 of the 50 patients who did not undergo excision. All 3 patients with upgrade would undergo excision. Thus, the proposed criteria would be comparable to or perhaps slightly more selective than our actual practice. We advocate selective excision with a multidisciplinary approach. Patients who do not undergo excision must be educated about the need for close radiologic follow-up.

Clinical Practice Points.

The clinical management of BP without atypia diagnosed on CNB is controversial. The reported upgrade rate in the literature ranges from 0% to 29%, with an overall upgrade rate of 5.4% (total patient number: 4037). Although some authors believe that BP without atypia can be managed safely with clinical and radiologic follow-up, many recommend excision to rule out any associated malignancy.

Our single-institution experience as a tertiary care center in a cohort of 80 patients with BP without atypia diagnosed on CNB demonstrated an upgrade rate of 3.8%. Mass lesions, lesions sampled by ultrasound-guided CNB, and palpable lesions were associated with surgical excision. None of the clinical, radiologic, or histologic features were predictive of upgrade.

Based on our study and a review of the literature, we propose criteria for surgical excision in this group of patients. Lesions with pathologic/radiologic concordance, those sampled by VAB and small asymptomatic lesions may be safely followed by imaging surveillance. When the proposed selection criteria were applied to our cohort, all patients with upgrade would undergo excision. We recommend selective surgical excision and advocate a multidisciplinary management approach for this group of patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kim-Anh Vu for excellent assistance on the figures and Ariana Trevino and Kelly Phan for their clerical support. This work is supported in part by the institutional start-up funds to LH from MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have stated that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Liberman L, Bracero N, Vuolo MA, et al. Percutaneous large-core biopsy of papillary breast lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:331–7. doi: 10.2214/ajr.172.2.9930777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mercado CL, Hamele-Bena D, Singer C, et al. Papillary lesions of the breast: evaluation with stereotactic directional vacuum-assisted biopsy. Radiology. 2001;221:650–5. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2213010005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim MJ, Kim SI, Youk JH, et al. The diagnosis of non-malignant papillary lesions of the breast: comparison of ultrasound-guided automated gun biopsy and vacuum-assisted removal. Clin Radiol. 2011;66:530–5. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lakhani SR, Ellis IO, Schnitt SJ, et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Breast. 4. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2012. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lam WW, Chu WC, Tang AP, et al. Role of radiologic features in the management of papillary lesions of the breast. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:1322–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bode MK, Rissanen T, Apaja-Sarkkinen M. Ultrasonography-guided core needle biopsy in differential diagnosis of papillary breast tumors. Acta Radiol. 2009;50:722–9. doi: 10.1080/02841850902977963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Page DL, Salhany KE, Jensen RA, et al. Subsequent breast carcinoma risk after biopsy with atypia in a breast papilloma. Cancer. 1996;78:258–66. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960715)78:2<258::AID-CNCR11>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ueng SH, Mezzetti T, Tavassoli FA. Papillary neoplasms of the breast: a review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:893–907. doi: 10.5858/133.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulligan AM, O’Malley FP. Papillary lesions of the breast: a review. Adv Anat Pathol. 2007;14:108–19. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e318032508d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen EL, Bentley RC, Baker JA, et al. Imaging-guided core needle biopsy of papillary lesions of the breast. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1185–92. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.5.1791185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agoff SN, Lawton TJ. Papillary lesions of the breast with and without atypical ductal hyperplasia: can we accurately predict benign behavior from core needle biopsy? Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:440–3. doi: 10.1309/NAPJ-MB0G-XKJC-6PTH. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sydnor MK, Wilson JD, Hijaz TA, et al. Underestimation of the presence of breast carcinoma in papillary lesions initially diagnosed at core-needle biopsy. Radiology. 2007;242:58–62. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2421031988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashkenazi I, Ferrer K, Sekosan M, et al. Papillary lesions of the breast discovered on percutaneous large core and vacuum-assisted biopsies: reliability of clinical and pathological parameters in identifying benign lesions. Am J Surg. 2007;194:183–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ko ES, Cho N, Cha JH, et al. Sonographically-guided 14-gauge core needle biopsy for papillary lesions of the breast. Korean J Radiol. 2007;8:206–11. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2007.8.3.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kil WH, Cho EY, Kim JH, et al. Is surgical excision necessary in benign papillary lesions initially diagnosed at core biopsy? Breast. 2008;17(3):258–62. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ivan D, Selinko V, Sahin AA, et al. Accuracy of core needle biopsy diagnosis in assessing papillary breast lesions: histologic predictors of malignancy. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:165–71. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Renshaw AA, Derhagopian RP, Tizol-Blanco DM, et al. Papillomas and atypical papillomas in breast core needle biopsy specimens: risk of carcinoma in subsequent excision. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:217–21. doi: 10.1309/K1BN-JXET-EY3H-06UL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carder PJ, Garvican J, Haigh I, et al. Needle core biopsy can reliably distinguish between benign and malignant papillary lesions of the breast. Histopathology. 2005;46:320–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sohn V, Keylock J, Arthurs Z, et al. Breast papillomas in the era of percutaneous needle biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(10):2979–84. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9470-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zografos GC, Zagouri F, Sergentanis TN, et al. Diagnosing papillary lesions using vacuum-assisted breast biopsy: should conservative or surgical management follow? Onkologie. 2008;31:653–6. doi: 10.1159/000165053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett LE, Ghate SV, Bentley R, et al. Is surgical excision of core biopsy proven benign papillomas of the breast necessary? Acad Radiol. 2010;17:553–7. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang JM, Han W, Moon WK, et al. Papillary lesions initially diagnosed at ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted breast biopsy: rate of malignancy based on subsequent surgical excision. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2506–14. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1617-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swapp RE, Glazebrook KN, Jones KN, et al. Management of benign intraductal solitary papilloma diagnosed on core needle biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1900–5. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2846-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sohn YM, Park SH. Comparison of sonographically guided core needle biopsy and excision in breast papillomas: clinical and sonographic features predictive of malignancy. J Ultrasound Med. 2013;32:303–11. doi: 10.7863/jum.2013.32.2.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puglisi F, Zuiani C, Bazzocchi M, et al. Role of mammography, ultrasound and large core biopsy in the diagnostic evaluation of papillary breast lesions. Oncology. 2003;65:311–5. doi: 10.1159/000074643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liberman L, Tornos C, Huzjan R, et al. Is surgical excision warranted after benign, concordant diagnosis of papilloma at percutaneous breast biopsy? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:1328–34. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mercado CL, Hamele-Bena D, Oken SM, et al. Papillary lesions of the breast at percutaneous core-needle biopsy. Radiology. 2006;238:801–8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2382041839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shin HJ, Kim HH, Kim SM, et al. Papillary lesions of the breast diagnosed at percutaneous sonographically guided biopsy: comparison of sonographic features and biopsy methods. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:630–6. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skandarajah AR, Field L, Yuen Larn Mou A, et al. Benign papilloma on core biopsy requires surgical excision. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2272–7. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9962-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rizzo M, Lund MJ, Oprea G, et al. Surgical follow-up and clinical presentation of 142 breast papillary lesions diagnosed by ultrasound-guided core-needle biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1040–7. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9780-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tseng HS, Chen YL, Chen ST, et al. The management of papillary lesion of the breast by core needle biopsy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:21–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bernik SF, Troob S, Ying BL, et al. Papillary lesions of the breast diagnosed by core needle biopsy: 71 cases with surgical follow-up. Am J Surg. 2009;197:473–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakr R, Rouzier R, Salem C, et al. Risk of breast cancer associated with papilloma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:1304–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jaffer S, Nagi C, Bleiweiss IJ. Excision is indicated for intraductal papilloma of the breast diagnosed on core needle biopsy. Cancer. 2009;115:2837–43. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jung SY, Kang HS, Kwon Y, et al. Risk factors for malignancy in benign papillomas of the breast on core needle biopsy. World J Surg. 2010;34:261–5. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0313-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cyr AE, Novack D, Trinkaus K, et al. Are we overtreating papillomas diagnosed on core needle biopsy? Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:946–51. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1403-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang JM, Moon WK, Cho N, et al. Management of ultrasonographically detected benign papillomas of the breast at core needle biopsy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:723–9. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rozentsvayg E, Carver K, Borkar S, et al. Surgical excision of benign papillomas diagnosed with core biopsy: a community hospital approach. Radiol Res Pract. 2011;2011:679864. doi: 10.1155/2011/679864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rizzo M, Linebarger J, Lowe MC, et al. Management of papillary breast lesions diagnosed on core-needle biopsy: clinical pathologic and radiologic analysis of 276 cases with surgical follow-up. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:280–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shouhed D, Amersi FF, Spurrier R, et al. Intraductal papillary lesions of the breast: clinical and pathological correlation. Am Surg. 2012;78:1161–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fu CY, Chen TW, Hong ZJ, et al. Papillary breast lesions diagnosed by core biopsy require complete excision. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:1029–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2012.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brennan SB, Corben A, Liberman L, et al. Papilloma diagnosed at MRI-guided vacuum-assisted breast biopsy: is surgical excision still warranted? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:W512–9. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.8750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Philpotts LE, Shaheen NA, Jain KS, et al. Uncommon high-risk lesions of the breast diagnosed at stereotactic core-needle biopsy: clinical importance. Radiology. 2000;216:831–7. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.3.r00se31831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Irfan K, Brem RF. Surgical and mammographic follow-up of papillary lesions and atypical lobular hyperplasia diagnosed with stereotactic vacuum-assisted biopsy. Breast J. 2002;8(4):230–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2002.08408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shah VI, Flowers CI, Douglas-Jones AG, et al. Immunohistochemistry increases the accuracy of diagnosis of benign papillary lesions in breast core needle biopsy specimens. Histopathology. 2006;48:683–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arora N, Hill C, Hoda SA, et al. Clinicopathologic features of papillary lesions on core needle biopsy of the breast predictive of malignancy. Am J Surg. 2007;194:444–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carder PJ, Khan T, Burrows P, et al. Large volume “mammotome” biopsy may reduce the need for diagnostic surgery in papillary lesions of the breast. J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:928–33. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.057158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.El-Sayed ME, Rakha EA, Reed J, et al. Predictive value of needle core biopsy diagnoses of lesions of uncertain malignant potential (B3) in abnormalities detected by mammographic screening. Histopathology. 2008;53:650–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheng TY, Chen CM, Lee MY, et al. Risk factors associated with conversion from nonmalignant to malignant diagnosis after surgical excision of breast papillary lesions. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3375–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0637-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ahmadiyeh N, Stoleru MA, Raza S, et al. Management of intraductal papillomas of the breast: an analysis of 129 cases and their outcome. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2264–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0534-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maxwell AJ. Ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted excision of breast papillomas: review of 6-years experience. Clin Radiol. 2009;64:801–6. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang JM, Moon WK, Cho N, et al. Risk of carcinoma after subsequent excision of benign papilloma initially diagnosed with an ultrasound (US)-guided 14-gauge core needle biopsy: a prospective observational study. Eur Radiol. 2010;20:1093–100. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1649-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tse GM, Tan PH, Lacambra MD, et al. Papillary lesions of the breast—accuracy of core biopsy. Histopathology. 2010;56:481–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Youk JH, Kim EK, Kwak JY, et al. Benign papilloma without atypia diagnosed at US-guided 14-gauge core-needle biopsy: clinical and US features predictive of upgrade to malignancy. Radiology. 2011;258:81–8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Richter-Ehrenstein C, Tombokan F, Fallenberg EM, et al. Intraductal papillomas of the breast: diagnosis and management of 151 patients. Breast. 2011;20:501–4. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Holley SO, Appleton CM, Farria DM, et al. Pathologic outcomes of nonmalignant papillary breast lesions diagnosed at imaging-guided core needle biopsy. Radiology. 2012;265:379–84. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12111926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li X, Weaver O, Desouki MM, et al. Microcalcification is an important factor in the management of breast intraductal papillomas diagnosed on core biopsy. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;138:789–95. doi: 10.1309/AJCPTDQCHIWH4OHM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kibil W, Hodorowicz-Zaniewska D, Popiela TJ, et al. Vacuum-assisted core biopsy in diagnosis and treatment of intraductal papillomas. Clin Breast Cancer. 2013;13:129–32. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li JL, Wang ZL, Su L, et al. Breast lesions with ultrasound imaging-histologic discordance at 16-gauge core needle biopsy: can re-biopsy with 10-gauge vacuum-assisted system get definitive diagnosis? Breast. 2010;19:446–9. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ko KH, Jung HK, Youk JH, et al. Potential application of ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted excision (US-VAE) for well-selected intraductal papillomas of the breast: single-institutional experiences. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:908–13. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Youk JH, Kim MJ, Son EJ, et al. US-guided vacuum-assisted percutaneous excision for management of benign papilloma without atypia diagnosed at US-guided 14-gauge core needle biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:922–8. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maxwell AJ, Mataka G, Pearson JM. Benign papilloma diagnosed on image-guided 14 G core biopsy of the breast: effect of lesion type on likelihood of malignancy at excision. Clin Radiol. 2013;68:383–7. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2012.06.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]