Abstract

Purpose

It is controversial whether folate status is a risk factor for the development of asthma or other allergic diseases. This study was conducted to investigate whether indirect or direct exposure to folate and impaired folate metabolism, reflected as methylene-tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T polymorphism, would contribute to the development of asthma and other allergic diseases.

Methods

Electronic databases were searched to identify all studies assessing the association between folate status and asthma or other allergic diseases. Two reviewers independently assessed the eligibility of studies and extracted data. The relative risk (RR) or odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was calculated and pooled.

Results

Twenty-six studies (16 cohort, 7 case-control, and 3 cross-sectional studies) were identified. Maternal folic acid supplementation was not associated with the development of asthma, atopic dermatitis (AD), eczema, and sensitization in the offspring, whereas exposure during early pregnancy was related to wheeze occurrence in the offspring (RR=1.06, 95% CI=[1.02-1.09]). The TT genotype of MTHFR C677T polymorphism was at high risk of asthma (OR=1.41, 95% CI=[1.07-1.86]).

Conclusions

It is indicated that maternal folic acid supplementation during early pregnancy may increase the risk of wheeze in early childhood and that the TT genotype of MTHFR C677T polymorphism impairing folic acid metabolism would be at high risk of asthma development. These results might provide additional information for recommendations regarding forced folate consumption or folic acid supplements during pregnancy based on its well-established benefits for the prevention of congenital malformations. However, currently available evidence is of low quality which is needed to further elucidate.

Keywords: Folic acid; asthma; risk; review, systematic; meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of asthma has dramatically increased during the past decades as in other allergic diseases, but underlying mechanisms that account for this remarkable trend remain unclear.1,2 This allergy epidemic has been reported in relation to changes in environmental factors, which has generated intense interest in changes of lifestyle such as dietary patterns. One particular dietary component that has recently received much attention is folate, which functions as an essential cofactor for one-carbon transfers, primarily methyl groups, and relates to a complex network of biological processes that are vital to growth.3 Thus, it could directly influence the propensity for epigenetic modifications and might tilt the immunophenotypic balance in favor of allergic disease.

Since maternal folic acid (a synthetic form of folate) supplementation before and during pregnancy has been widely recommended to reach a protective effect on the occurrence of neural tube defects4,5 as well as other congenital malformations6 for many years, it has been questioned whether folic acid supplementation might be associated with the development of adverse health outcomes in the offspring. Previous findings in mice suggested that maternal dietary supplementation with methyl donors (including folic acid) leads to allergic disease in the offspring,7 and similar conditions were observed in humans.8,9 These results raised concern about possible adverse effects of folic acid supplementation during pregnancy on respiratory and allergic outcomes in the offspring. However, several studies have not detected any relationship.10,11,12,13 In addition, studies conducted to detect the role of impaired folate metabolism, reflected by polymorphism of the methylene-tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T in the development of asthma or other atopic diseases, have reported inconsistent results.14,15

Although several reviews do not support an exact effect of maternal folate status on asthma risk, the timing, course, and dose effect of folate status, and the association between MTHFR C667T polymorphisms and asthma risk are still of increasing interest.16,17,18,19 There is no adequate evidence to exclude such effects, either.16,18,19 Therefore, we performed this comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of existing evidence to answer the following questions: (1) whether indirect or direct exposure to folate is associated with the development of asthma and other allergic diseases, including atopic dermatitis (AD), eczema, and sensitization; (2) whether there is a dose-dependent relationship between folate status and allergic diseases; (3) whether this relationship could be interpreted by exposure timing; and (4) whether the manifestations could be objectively measured.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Searching and selection

Comprehensive literature search was performed using databases MEDLINE (PubMed), Cochrane Central, Web of Science, and EMBASE until August 2014. The following terms "folic" or "folate" in combination with "asthma," "wheeze," "allergy," "allergic," "AD," "eczema," "rhinitis," or "hay fever" was used as search terms to identify potential studies. The search strategies were adjusted on the basis of the characteristics of each database. Reference lists of all identified potential studies were manually screened to obtain other relevant articles. No language or initial time restriction was performed.

All trials conducted on humans involving the association of folate status and asthma or other allergic diseases were included except only abstracts or no available data. Replicative publications on the same population with the same outcomes (for example, Thuesen 201020 and Husemoen 200614) were evaluated, one of which with the largest sample size was included when performed meta-analysis.

Data extraction and management

Data was independently extracted by 2 reviewers (T.W. and H.P.Z.). For each study, the following details were extracted: study characteristics (country, study design, and sample size), folate status (reported as maternal use, personal use, objective measure, or gene polymorphism), the duration of follow-up, factors adjusted for the analysis, definition, and estimates of outcomes. To avoid confusing, variations in the definitions used for each outcome in original studies were unified. In this study, atopy was defined as any positive skin prick test (SPT), and sensitization was defined as a positive test for specific immunoglobulin E (sIgE) to at least one of the allergens tested. The Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale was used to evaluate the quality of eligible studies.21 A study with score ≥6 was considered to be of sufficient quality for our meta-analysis. In cases of disagreement, consensus was achieved following discussion with a third adjudicator (G.W.).

Statistical analysis

We followed the guidelines recommended by the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) Group.22 For dichotomous outcomes, the relative risk (RR) or odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was calculated. When original data had been adjusted for potential confounding factors, adjusted estimates were pooled using the generic inverse variance method. The associations between maternal folate/folic acid status at different gestation periods (prepregnancy, early pregnancy, including the first trimester, whole pregnancy or other periods) and asthma/wheeze or other allergic outcomes were investigated. Heterogeneity was examined using the chi-square test with P<0.10 indicating significant heterogeneity, and a I-square (I2) statistic greater than 50% indicated moderate or high heterogeneity. The fixed-effects model was used for the meta-analysis if there was no significant heterogeneity (I2<50%); otherwise, the random-effects model. The Z test was used to determine the significance of the pooled estimates. Funnel plots and the Egger test were used to investigate study size effects indicating possible publication bias when outcomes were reported in at least 10 studies. Statistical analysis was conducted with Stata 11.0 (Stata Corp. LP, College Station, TX, USA), and a 2-sided P value less than 0.05 was regarded as significant.

The quality of the evidence related to the estimation of the association between maternal folic acid supplementation and asthma/wheeze or other allergic diseases in childhood or between MTHFR C667T polymorphisms and asthma risk followed the suggestions of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group by using the GradePro software (version 3.6).23

RESULTS

Trials included, study characteristics and quality of reporting

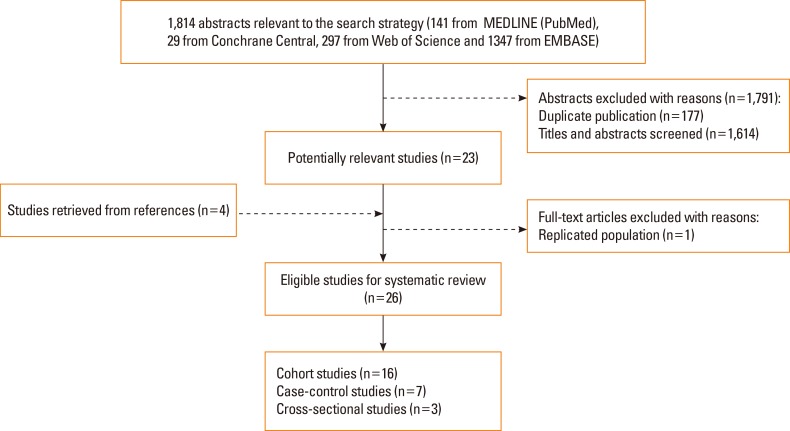

The primary search strategy initially yielded a total of 1,814 citations from MEDLINE (PubMed) (n=141), Cochrane Central (n=29), Web of Science (n=297), and EMBASE (n=1,347). After removing duplicates and scanning the titles and abstracts, 23 articles were left over. After full-text reading and reference tracing, 26 eligible studies 8,9,10,11,12,13,15,20,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41 remained (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Flowchart of study selection.

The characteristics of the studies included are summarized in Tables S1, 2, 3 as supplementary data. Among these studies, 16 were cohort,8,9,10,11,12,13,20,24,27,31,34,35,36,37,38,41 7 were case-control,25,26,28,29,32,33,39 and 3 were cross-sectional15,30,40 studies. The studies were undertaken in the US, the UK, the Netherlands, Denmark, Finland, Australia, Norway, Egypt, Korea, Japan, and India. The sample size ranged from 40 to 32,077. In the cohort studies, the follow-up duration ranged from 1 to 8 years. In birth cohort studies, the follow-up duration was more than 1 year for wheeze and 3 years for asthma. No eligible studies involving the development of hay fever were found.

Among the cohort studies, 12 (n=60,560) investigated the association between maternal folate exposure and asthma/wheeze incidence,8,9,10,11,12,13,24,27,31,37,38,41 while 4 (n=9,073) investigated the relationship between folate status at baseline and progress of concerned diseases.20,34,35,36 Of all the case-control studies, 5 (n=5,023) investigated the association between folate status and asthma/wheeze,26,28,29,33,39 and the remaining 2 (n=462) evaluated the association between folate status and AD.25,32

Of the cross-sectional studies, 3 (n=10,891) investigated the association between folate status and targeted diseases.15,30,40 These studies mainly focused on the association of measurable folate concentration and the genotypes of subjects with specific outcomes.

The quality score of cohort studies ranged from 6 to 9 (mean 7.63, SD 1.09) (Table S1 for supplementary data), and that of case-control studies ranged from 4 to 8 (mean 6.71, SD 1.50) (Table S2 for supplementary data). All studies except 133 described the definition of specific outcomes.

Folate and asthma

The incidences of asthma in the offspring with maternal folic acid supplementation during pregnancy (compared to no use) were pooled in 3 cohort studies.10,11,12 There was an insignificant overall effect of maternal folic acid supplementation on the risk of asthma (RR=1.04, 95% CI=[0.94-1.16]). Also, no statistically significant differences in such relationships were observed before conception (RR=0.98, 95% CI=[0.73-1.33]), during early pregnancy (RR=0.98, 95% CI=[0.78-1.23]), or during other periods (RR=1.03, 95% CI=[0.92-1.16]) (Table 1).

Table 1. Effects of folate status on the development of asthma, wheeze, or other allergic diseases.

| Outcome | Exposure timing types of folic acid | Timing of assessment | Folic acid use, RR (95% CI)* | Heterogeneity (I2, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma | Any use10,11,12 | At 6 yr10, 3-8 yr11, at 6-7 yr12 | 1.04 (0.94-1.16) | 0.0 |

| Pre-pregnancy9,10 | At 3.5 yr and 5.5 yr9, at 6 yr10 | 0.98 (0.73-1.33) | 0.0 | |

| Early pregnancy9,10,12 | At 3.5 yr and 5.5 yr9, at 6 yr10, at 6-7 yr12 | 0.98 (0.78-1.23) | 0.0 | |

| Other period in pregnancy11,12 | 3-8 yr11, at 6-7 yr12 | 1.03 (0.92-1.16) | 0.0 | |

| Wheeze | Any use11,12 | 1-8 yr11, until 6-7 yr12 | 1.05 (0.95-1.15) | 0.0 |

| Early pregnancy8,12,13 | 6-18 mo8, until 6-7 yr12, up to 4 yr13 | 1.06 (1.02-1.09)† | 0.0 | |

| Other period in pregnancy8,11,12 | 6-18 mo8, 1-8 yr11, until 6-7 yr12 | 1.01 (0.98-1.03) | 0.0 | |

| Atopic Dermatitis | Early pregnancy12,13 | at 2 yr12, up to 4 yr13 | 1.15 (0.91-1.45) | 0.0 |

| Eczema | Other period in pregnancy11,12 | 1-8 yr11, until 6-7 yr12 | 0.99 (0.89-1.10) | 0.0 |

| Sensitization | Other period in pregnancy11,12 | At 8 yr11, at 2 yr12 | 0.88 (0.75-1.03) | 0.0 |

*vs no folic acid use; †P=0.001. RR, risk ratio; CI, confidence intervals.

Because of significant heterogeneity in measurement and outcome reporting, data about the relationship of the measurable folate level with asthma risk was not pooled. Two studies investigated the association between the measurable maternal folate level and asthma in the offspring. The cohort study by Magdelijns et al.12 showed that higher maternal intracellular folic acid levels in pregnancy tend to decrease risk of childhood asthma in a dose-dependent manner (P for trend=0.05). The case-control study by Haberg et al.26 found a trend of increasing risk of asthma for children aged 3 years across quintiles of maternal plasma folate levels in pregnancy (P for trend=0.006).

Five studies investigated the relationship of maternal folate concentration with risk of asthma. No significant association between the serum folate level and asthma onset29,30,34 or airway inflammation features of asthma (FENO, total IgE level, or the number of positive SPT)36 was found in 3 studies. Thuesen et al.20 found a significant inverse association between serum folate levels and risk of physician-diagnosed asthma, which is similar to that of a previous report.39 Recently, van der Valk et al.34 showed that folate levels of children at birth did not predict asthma-related outcomes up to the age of 6 years.

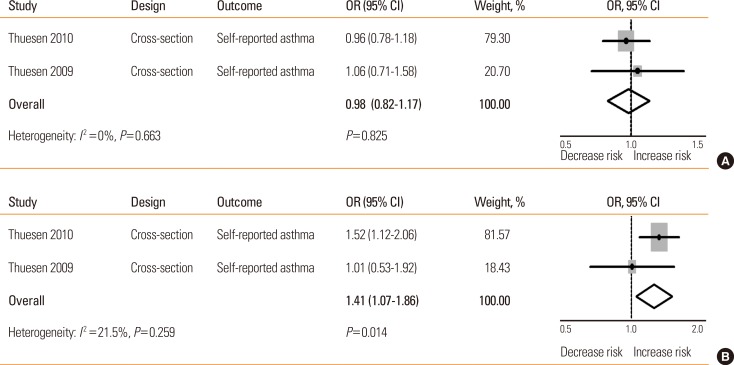

Four studies of case-control or cross-sectional design explored the association between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and asthma,15,20,27,33 but only 2 provided available effect measures.15,20 No significant association was found between the MTHFR C677T CT genotype and asthma development (OR= 0.98, 95% CI=[0.82-1.17]), but the TT genotype was at risk of asthma in adults (OR=1.41, 95% CI=[1.07-1.86]) (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Table 2. The relationship between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and the risk of asthma or other allergic diseases.

| Outcome | Genotypes | OR (95% CI)* | Heterogeneity (I2, %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma | CT genotype15,20 | 0.98 (0.82-1.17) | 0.0 |

| TT genotype15,20 | 1.41 (1.07-1.86)† | 21.5 | |

| Atopy | CT genotype15,27 | 1.05 (0.92-1.19) | 0.0 |

| TT genotype15,27 | 0.93 (0.76-1.14) | 0.0 | |

| Sensitization | CT genotype15,20 | 0.99 (0.89-1.10) | 0.0 |

| TT genotype15,20 | 1.03 (0.86-1.23) | 0.0 |

*vs the CC genotype; †P=0.014. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence intervals.

Fig. 2. The relationship between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and asthma risk. (A) CT vs CC; (B) TT vs CC. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence intervals.

Folate and wheeze

Two studies explored the relationship between maternal folic acid supplementation during pregnancy (compared to no use) and wheeze incidence in the offspring,11,12 and showed the insignificant overall effect of folic acid supplementation on the risk of wheeze (RR=1.05, 95% CI=[0.95-1.15]) (Table 1).

Three cohort studies investigated the relation of maternal folic acid supplementation during early pregnancy with the occurrence of wheeze in the offspring8,12,13 and found a significant pooled effect of maternal folic acid supplementation during early pregnancy on the incidence of offspring wheeze (RR= 1.06, 95% CI=[1.02-1.09]) (Fig. 3). No association was found between maternal folic acid supplementation during other periods and risk of wheeze in childhood (RR=1.01, 95% CI=[0.98-1.03]).

Fig. 3. The relationship between maternal folic acid supplementation during early pregnancy and risk of wheeze in childhood. *Four weeks before conception until 8 weeks after conception and/or during the first trimester of pregnancy. RR, risk ratio; CI, confidence intervals.

No significant dose-response relationship was observed between maternal folic acid supplementation during pregnancy and the risk of wheeze.10,24,31 Furthermore, a recently published study did not find that early-life folate levels measured at ages 2, 4, 6, and 8 years were associated with asthma or wheeze at 6 years.35 Kiefte-de Jong et al.13 found no association between maternal MTHFR C677T polymorphism and wheeze in the offspring.

Folate and other allergic diseases

No association of maternal folic acid supplementation during early pregnancy with the occurrence of offspring AD was found (RR=1.15, 95% CI=[0.91-1.45]) (Table 1). For eczema and sensitization reflected by sIgE status in the offspring, the association also did not reach statistically significant difference (Table 1).

Magdelijns et al.12 also did not observe the relationship between maternal use of folic acid supplements during pregnancy and increased risk of AD at 2 years. A study by Oh et al.25 found that intake of antioxidants nutrients, including folic acid, was negatively associated with AD development (OR=0.37, 95% CI=[0.18-0.73]). A cohort study by Kim et al.41 found that a maternal serum folate level of ≥9.5 ng/mL during mid-pregnancy was inversely associated with AD risk at 24 months (OR=0.52, 95% CI=[0.31-0.88]). A case-control study by Shaheen et al.32 found that serum folic acid levels were lower in AD patients than in the control subjects, although this did not reach statistical significance. Kiefte-de Jong et al.13 found no association between maternal MTHFR C677T polymorphism and AD in the offspring.

Two studies investigated the association of the MTHFR C677T polymorphism with atopy or sensitization.15,20 Pooled analyses did not indicate the association between the MTHFR C677T polymorphism and atopy or sensitization (Table 2).

Assessment of the quality of evidence for the association between folate status and the development of asthma/wheeze or other allergic diseases

Evidence from observational studies was graded from low quality in term of the relatively higher level of heterogeneity or higher risk bias compared to randomized controlled trials.42 Furthermore, we performed the analyses at consistent exposure time that would reduce unexplained heterogeneity of the results. As a result, the quality of evidence related to the estimation of association between maternal folic acid supplementation and asthma/wheeze in childhood was very low (Table 3). Likewise, although genotyping is an objective definition, the quality of evidence related to the estimation of the association between MTHFR C667T polymorphisms and asthma, atopy, or sensitization risk was graded as low (Table 4). The overall quality of evidence was not upgraded due to lack of large effects or dose-response relationships.

Table 3. The quality of evidence assessment of association between maternal folic acid supplementation and asthma/wheeze in childhood by the GRADE approach.

| Outcomes | Exposure timing | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of evidence (GRADE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma in childhood | ||||

| Pregnancy10,11,12 | RR=1.04 (0.94-1.16) | 7,925 (n=3) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖Low 1 | |

| Pre-pregnancy9,10 | RR=0.98 (0.73-1.33) | 2,056 (n=2) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖Very Low 2 | |

| Early pregnancy9,10,12 | RR=0.98 (0.78-1.23) | 4,696 (n=3) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖Low 3 | |

| Other period in pregnancy11,12 | RR=1.03 (0.92-1.16) | 6,426 (n=2) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖Low 4 | |

| Wheeze in childhood | ||||

| Pregnancy11,12 | RR=1.05 (0.95-1.15) | 6,426 (n=2) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖Low 5 | |

| Early pregnancy8,12,13 | RR=1.06 (1.02-1.09) | 43,459 (n=3) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖Low 6 | |

| Other period in pregnancy8,11,12 | RR=1.01 (0.98-1.03) | 38,503 (n=3) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖Low 7 | |

| Atopic Dermatitis | Early pregnancy12,13 | RR=1.15 (0.91-1.45) | 11,382 (n=2) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖Very Low 8 |

| Eczema | Other period in pregnancy11,12 | RR=0.99 (0.89-1.10) | 6,426 (n=2) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖Low 9 |

| Sensitization | Other period in pregnancy11,12 | RR=0.88 (0.75-1.03) | 6,426 (n=2) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖Low 10 |

1 No factors exist that can reduce or increase the quality of evidence.

2 (-1 imprecision) 95% CI overlaps no effect (CI includes RR of 1.0) and CI fails to exclude 0.75 and 1.25 though the sample size is very large.

3 No factors exist that can reduce or increase the quality of evidence.

4 No factors exist that can reduce or increase the quality of evidence.

5 No factors exist that can reduce or increase the quality of evidence.

6 No factors exist that can reduce or increase the quality of evidence.

7 No factors exist that can reduce or increase the quality of evidence.

8 (-1 imprecision) 95% CI overlaps no effect (CI includes RR of 1.0) and CI fails to exclude 1.25 though the sample size is very large.

9 No factors exist that can reduce or increase the quality of evidence.

10 No factors exist that can reduce or increase the quality of evidence.

RR, risk ratio; CI, confidence intervals.

Table 4. The quality of evidence assessment of association MTHFR C667T polymorphisms and asthma risk by the GRADE Approach.

| Outcomes | Comparisons | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of evidence (GRADE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma | CT vs CC15,20 | OR=0.98 (0.82-1.17) | 7,991 (n=2) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖Low 1 |

| TT vs CC15,20 | OR=1.41 (1.07-1.86) | 7,991 (n=2) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖Low 2 | |

| Atopy | CT vs CC15,27 | OR=1.05 (0.92-1.19) | 6,571 (n=2) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖Low 3 |

| TT vs CC15,27 | OR=0.93 (0.76-1.14) | 6,571 (n=2) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖Low 4 | |

| Sensitization | CT vs CC15,20 | OR=0.99 (0.89-1.10) | 7,991 (n=2) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖Low 5 |

| TT vs CC15,20 | OR=1.03 (0.86-1.23) | 7,991 (n=2) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖Low 6 |

Quality of evidence (GRADE) as in Table 3.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence intervals.

DISCUSSION

Along with an increasing number of studies investigating the association between folate status and allergic outcomes, conflicts in this field have been on the rise. Thus, current metaanalyses provide no evidence for the relationship of maternal folic acid supplementation during pregnancy with asthma, AD, eczema, or sensitization in the offspring except that an increased risk of wheeze in childhood related to maternal folic acid supplementation during early pregnancy was observed. In addition, our meta-analysis found no evidence for any association between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and targeted outcomes except that the TT genotype was associated with asthma.

Blatter et al.16 reviewed the relationship between folate and asthma and did not support excessive worry about the adverse effect of maternal folate supplementation during pregnancy on asthma, although there was no adequate data to exclude a weak or modest effect. Brown et al.19 summarized epidemiologic evidence from 10 large prospective cohort studies supporting or refuting the relationship between maternal folate exposure in pregnancy and asthma/allergy in the offspring. A previous meta-analysis conducted by Crider et al.18 did not support the association between folic acid supplementation in the periconceptional period or the first trimester and risk of asthma, but the sensitivity analysis of combined asthma and wheeze showed a significant association. Given a diagnosis of asthma is difficult to establish in infants and toddlers but a diagnosis of symptoms, such as wheeze, are more suitable, it seems better to evaluate the effect of maternal folic acid supplementation during pregnancy on wheeze rather than asthma. A study by Haberg et al.8 reviewed in the 2 meta-analyses reported an increased risk of wheeze between the ages of 6 and 18 months, which is consistent with the result of Bekkers' study11 in which an increased risk of wheeze was reported at age 1 year but not at later ages. Bekkers et al.11 evaluated the effects of maternal folic acid supplementation during pregnancy on wheeze or asthma, respectively, from age 1 or 3 years to 8 years and reported an increased risk association with wheeze but not asthma. Thus, we speculated that not all children with wheeze in early life has a diagnosis of asthma in later life and as time goes on, the effect of maternal folate status on respiratory health in the offspring goes down. However, both of these findings were driven by the large cohort study conducted by Haberg et al.,8 which weighted 89% of the summary estimate in the Crider's study18 and 92% in this study. To address the question of a possible causal association between maternal folic acid status in pregnancy and risk of asthma or wheeze in children, a number of additional studies or analyses should be undertaken considering the misclassification of wheeze and asthma with age factor and follow-up duration.

To better understand the possible association, timing of folate intake during pregnancy should be taken into consideration. Since most clinical trials reviewed in this article provided direct evidence that there is no association between maternal folic acid supplementation during pregnancy and asthma,10,11,12 wheeze,11,12,13 shortness of breath,13 AD,12,13 or eczema,11,12 objective measurements, including allergic sensitization and bronchial hyperresponsiveness, should be made.11 Nevertheless, studies referred to maternal folic acid supplementation at different periods during pregnancy seemed to have different results. Whitrow et al.9 reported that maternal folic acid supplementation in late pregnancy (30-34 weeks) increased the risk of childhood asthma at 3.5 years. Bekkers et al.11 assessed the risk at similar exposure time (median 33 weeks) and reported an increased risk of wheeze at age 1 year. Moreover, Haberg et al.8 found that early pregnancy (any 4-week-period during weeks 0-12 in pregnancy) increased the risk of childhood wheeze in infants up to 18 months. Because widespread DNA methylation programming occurs in the early embryo, the association between maternal folate status during early pregnancy and respiratory health in early childhood might receive more attention.

Although several studies measured direct or indirect folate exposure and investigated a dose-respond association of folate with allergic outcomes, it is not possible to do quantitative analyses due to diverse exposure assessments. Both positive13,26,31 and negative12,20,30 correlations were observed in current evidence. It is possible that these inconsistences reflect complex relationships between direct or indirect folate exposure and the risk of asthma/wheeze or other allergic outcomes. Recent studies showed that folate levels measured in early life did not affect asthma-related outcomes.34,35 Interestingly, another study conducted by Lin et al.36 found "bell-shaped" relationships between serum folate and some inflammatory biomarkers of asthma. Likewise, nonlinear relationships were found between serum folate levels and fractional exhaled nitric oxide, total IgE, or the frequency of positive SPTs. The folate level in the second quartile was significantly associated with increased total IgE when compared to the first quartile (the lowest). However, the levels of inflammatory biomarkers in the third or fourth (the highest) quartiles were similar to those in the first quartile and had no association with folate levels. Therefore, high-quality evidence is needed to interpret this complex network. For future studies, objective measurements can be included, and plasma folate concentration might be a better biomarker. In addition, measurements should be taken into account to evaluate not only indirect folate exposure resulting from mothers during pregnancy, but also the folate status of subjects themselves. The dose, timing, and source of folate exposure should also be considered.

The MTHFR gene encodes the protein for making an enzyme called methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase that catalyzes the conversion of 5, 10-methylenetetrahydrofolate to 5-methyltetrahydrofolate, which is required for the conversion of homocysteine to methionine. MTHFR C677T polymorphism was assumed to be associated with the risk of asthma. An association was reported by Zhou et al.33 that the TT genotype significantly increases the risk of atopic asthma compared to all of the CC and CT genotypes. However, subsequent studies found no association between maternal MTHFR C677T polymorphism and asthma,27 wheeze,13 or AD13 in the offspring or mothers themselves.27 Our meta-analysis found no evidence of the association between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and targeted outcomes except that the TT genotype was associated with asthma. In addition, a previous study found a significant interaction between MTHFR C677T and folate levels.34 Because DNA genotyping is assigned at birth and as an objective measurement, utilizing such methods could help reduce measurement biases and help explore a causal association. Thus, intrinsic genetic factors that could impair folate metabolism for a long time might play an important role in the occurrence and development of asthma. However, because folate status is largely influenced by dietary intake, this hypothesis still needs to be confirmed by further studies, and interpretations of these complex relationships should be presented with caution.

Although this study has referred to almost all of the existing evidence we could acquire, limitations of this study should be noted. First, since the articles included in this study were not randomized controlled trials, some obvious or hidden confounding factors may be unavoidable more or less. Second, potential risk of bias resulting from differences in study design, outcomes assessment, measurements or follow-up performance might produce heterogeneity. Third, the dose-response relationship was not analyzed due to limited eligible studies. Fourth, although asthma or other allergic diseases are associated with both genetic and environmental effects,43 it is difficult to analyze potential interactions between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and environmental factors, such as dietary intake, due to lack of data.

In conclusion, our study indicates that maternal folic acid supplementation during early pregnancy might increase the risk of wheeze in early childhood and that the TT genotype of MTHFR C677T polymorphism impairing folic acid metabolism would be at high risk of asthma development. These results can provide additional information for recommendations regarding forced folate consumption or folic acid supplementation in pregnancy based on its well-established benefits for the prevention of congenital malformations. Further studies are needed to elucidate whether there is a critical window of susceptibility that may reduce risk of neural tube defects without increased risk of asthma or other allergic diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was partly supported by a grant from National Natural Science Foundation of China (30971326, 31450007, 81171320, 81241002, and 81370122), Sichuan Youth Science and Technology Foundation (No. 2010JQ0008), Youth Science Funding of Sichuan University (2011SCU04B17), and Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-12-0380). The funders played no role in study design, data collection and analysis, preparation of the manuscript, or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

There are no financial or other issues that might lead to conflict of interest.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. The characteristics of studies included in the systematic review on the relationship between folate status and asthma, wheeze or other allergic diseases (cohort study).

| Study | Study Design; follow-up time | Definition of Outcomes | Measurement of Folate/Folic Acid Status | Main Findings | Study Limitations | Adjusted Factors | Quality Assessment Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim 20141 | Birth cohort study of 917 children in South Korea, carried out from 2006-2011, embed in the MOCEH study; 2 yr | Asthma: physician-diagnosed or treatment for asthma in past year AD: physician-diagnosed or treatment for AD in past year |

Serum folate level | Increased maternal folate level during mid-pregnancy was associated with a decreased risk of LRTIs at 6 mo and AD at 24 mo | Potential selection bias due to the substantial loss of follow-up (~50%) at 24 mo, no assessment of maternal folate status in the early pregnancy | Baby's sex, birth weight, gestational age, and duration of breastfeeding, and maternal age, the history of allergic diseases such as AD, asthma, allergic rhinitis, and allergic conjunctivitis, the urinary cotinine levels in mid- and late-pregnancy, and the prepregnancy, BMI | 7 |

| van der Valk 20132 | Birth cohort study of 2001 children in Netherlands, carried out from 2002-2006, embedded in the Generation R study; 6 yr | Asthma: physician-diagnosed Wheeze: using questions from the ISAAC Eczema: physician-diagnosed or self-reported |

Cord blood folate, MTHFRC677T polymorphism | No significant association between folate level at birth and wheeze or eczema until 4 yr, or asthma and eczema ever. Genetic mutations in MTHFRC677T and higher folate levels were associated with increased risk of eczema until 4 yr | Lack of data on maternal folate status, potential selection bias due to missing cord blood samples | Maternal age, BMI, educational level at intake, history of maternal atopy or asthma, parity, smoking, folic acid supplement use and pet keeping during pregnancy, and children's sex, gestational age, birth weight and day care attendance, based on the significance of their associations with repeated wheezing (P < 0.05), or a change in effect estimate of > 10% | 8 |

| Okupa 20133 | Cohort study of 138 children (2-9 yr) in USA, carried out from 1998, embedded in the COAST study; 8 yr | Asthma: physician-diagnosed and/or the use of asthma medication Sensitization: 1 or more positive (>0.34) specific IgE results |

Plasma folate level | Higher plasma folate levels at or before age 6 yr were associated with allergic sensitization but not with IgE production, wheeze, or asthma at age 6 yr | Small sample size, no assessment of dietary intake, and limited adjustment for covariates | Gender and socioeconomic status | 6 |

| Lin 20134 | Cohort study of 150 children (5-17 yr) in USA; 1 yr | Asthma: long-term controller medication for asthma or meeting National Asthma Education and Prevention Program guideline Atopy: at least 1 positive skin prick test (SPT) result |

Serum folate level | Serum folate level was not significantly associated with FENO, the number of positive SPTs, lung function, or hospitalizations for asthma. A folate level in the second quartile was associated with increased total IgE when compared with the lowest folate level. Increased serum folate level was associated with less exercise-related symptoms | Small sample size, no assessment of dietary intake, lack of multiple testing corrections, and limited adjustment for covariates | Age, sex, and education | 6 |

| Martinussen 20125 | Birth cohort study of 1,499 children in USA, carried out from 1997-2000, embedded in the AIP and later the PRAM study; 6 yr | Asthma: physician diagnosed and current symptoms | Maternal folic acid supplement | No significant association between maternal folate supplement in the first trimester and childhood asthma at 6 age yr | Lake of date on maternal dietary intake | Maternal marital status, family income, and maternal asthma. | 9 |

| Bekkers 20126 | Birth cohort of 3,786 children in Netherlands, carried out from 1996-1997, embedded in the PIAMA study; 8 yr | Asthma: symptoms and/or doctor-diagnosed Wheeze: at least one attack of wheeze Eczema: an itchy rash that came and went on typical eczema sites Sensitization: serum IgE ≥0.70 IU/mL-1 |

Maternal folic acid supplement | Maternal folic acid use was associated with wheeze at age 1 yr and eczema at age 7 yr. No overall (from 1 to 8 yr of age) associations between maternal folic acid supplementation and (frequent) asthma symptoms, wheeze, LRIs and eczema | Lack of data on maternal dietary intake | Maternal education, maternal allergy, maternal smoking during pregnancy and number of older siblings | 9 |

| Kiefte-de 20127 | Birth cohort study of 8,742 children in Netherlands, carried out from 2002-2006, embedded in the Generation R study; 4 yr | Wheeze: symptoms, ISAAC AD: doctor-diagnosed |

Maternal MTHFR C677T polymorphism, maternal folic acid supplement, and maternal plasma folate | Higher maternal plasma folate level in early pregnancy was associated with increased prevalence of AD but not with wheeze and shortness of breath at age 4 yr | No assessment of maternal dietary intake, and measured plasma folate level at a very early stage in pregnancy (13±2.0 wk of gestation) | Time, maternal ethnicity, parental atopic constitution, parity, maternal BMI, maternal age, breastfeeding duration, daycare attendance, maternal educational level, maternal smoking and alcohol consumption, and fetal gender and birth weight SD score derived from generalized estimation equations. | 8 |

| Dunstan 2012 8 | Birth cohort of 484 children in Australia; 1 yr | Asthma: recurrent wheeze to be responsive to bronchodilator medications Eczema: typical skin lesions Food Allergy: IgE-mediated food allergy and a positive SPT to the implicated food Sensitization: SPT positive |

Folate consumption from foods and folic acid supplement, maternal and cord blood serum folate level | Maternal folate taken as a supplement in higher doses during the third trimester was significant associated with eczema at age 1 yr. With cord folate levels <50 nmol/L and >75 nmol/L was associated with greater sensitization risk than levels between 50 and 75 nmol/L | Short duration of follow-up and limited adjustment of covariates | Maternal allergy and infant postnatal diet | 6 |

| Magdelijns 20119 | Birth cohort of 2,640 children in Netherlands, carried out from 2000, embedded in the KOALA Birth Cohort Study; 6-7 yr | Asthma: physician-diagnosed with clinical symptoms and/or asthma medication use Wheeze: parents report Eczema: parents report AD: symptoms, UK Working Party criteria Sensitization: sIgE >0.3 IU/mL for ≥1 of the tested allergens |

Maternal folic acid supplement and intracellular folic acid level | No significant association between maternal folic acid supplement use during pregnancy and AD and sensitization at age 2 yr, or wheeze, lung function, asthma, and eczema at age 6-7 yr. Maternal folate level in erythrocytes in late pregnancy was inversely associated with asthma at age 6-7 yr.] (P=0.05) | No assessment of maternal dietary intake, potential selection bias due to loss of follow-up, and no assessment of folate level in early pregnancy | Maternal antibiotic use during pregnancy, maternal smoking during pregnancy, maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy, mode and place of delivery, birthweight, gender of the child, treatment with antibiotics during the first 6 mo of life, breastfeeding during the first 2 yr of life, exposure to domestic animals during pregnancy and the first 2 yr of life, exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in the first 6 to 7 yr of life, siblings, family history, recruitment group, maternal education level, daycare, and other supplement use during pregnancy. | 8 |

| Nwaru 201110 | Birth cohort of 2,441 children in Finland, carried out from 1996-1997, embedded in the Finnish Type 1 Diabetes Prediction and Prevention study; 5 yr | Asthma: physician-diagnosed plus either any wheezing symptom or asthma medication use in the past 12 mo, ISAAC Eczema: parents report |

Maternal folate consumption from foods and folic acid supplement | No significant associations between maternal folate intake and eczema at age 5 yr | Potential recall bias | Sex of child, place of birth, season of birth, gestational age at birth, maternal age at birth, maternal basic education, maternal smoking during pregnancy, mode of delivery, number of siblings, parental asthma, parental allergic rhinitis, pets at home at 1 yr of age, and atopic eczema by 6 mo of age. | 9 |

| Miyake 201111 | Birth cohort of 763 children in Japan, carried out from 2001-2003, embedded in the OMCHS study; 16-24 mo | Wheeze: had symptom 12 mo pre based on the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) criteria Eczema: had symptom, ISAAC |

Maternal folate consumption from foods | No significant association between maternal consumption of folate during pregnancy and wheeze or eczema at age 16-24 mo | No assessment of maternal folate supplementation, lack of analysis of folate intake at different stage of pregnancy, and potential selection bias | Maternal age, gestation at baseline, residential municipality at baseline, family income, maternal and paternal education, maternal and paternal history of asthma, atopic eczema, and allergic rhinitis, changes in maternal diet in the previous 1 mo, season when data at baseline were collected, maternal smoking during pregnancy, baby's older siblings, baby's sex, baby's birth weight, household smoking in same room as infant, breastfeeding duration, age at which solid foods were introduced, age of infant at the third survey, and maternal intake of docosahexaenoic acid, n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids, vitamin D, calcium, vitamin E, and b-carotene during pregnancy. | 8 |

| Thuesen 201012 | Cohort study of 6,784 adults (30-60 yr) in Denmark, carried out from 1999-2001, embedded in the Inter99 study; 5 yr | Asthma: self-reported doctor-diagnosed Atopy: specific IgE ≥0.35kU/l to at least one of the four allergens |

Dietary intake of folate, serum folate level and MTHFRC677T polymorphism | Low serum folate level and the TT genotype of the MTHFR-C677T polymorphism were associated with increased prevalence of self-reported doctor-diagnosed asthma at baseline | Lake of data on vitamin supplements, limited analysis of longitudinal data with 5-yr follow-up, and potential bias due to loss of follow-up | Age, sex, total energy intake, smoking, alcohol intake, BMI, and socioeconomic status | 7 |

| Whitrow 200913 | Birth cohort study of 557 children in Australia, carried out from 1998-2000, embedded in the Generation 1 cohort study; 5.5 yr | Asthma: physician-diagnosed | Maternal folate consumption from foods and folic acid supplement | Maternal folic acid supplementation in late pregnancy significantly increase the risk of asthma 3.5 yr and of persistent asthma at 3.5 and 5.5 yr | No assessment of folate level, and potential selection bias due to loss of follow-up | Maternal education, maternal age, parity, gravida, gestational age, maternal asthma status, and breastfeeding (partial or full for <3 mo) | 9 |

| Haberg 200914 | Birth cohort study of 32,077 children in Norway, carried out from 2000-2005, embedded in the MoBa study; 1.5 yr | Wheeze: had symptom | Maternal folic acid supplement | Maternal folate supplementation in the first trimester was associated with increased risk of wheeze and LRI up to 18 mo of age | No assessment of dietary intake | Other vitamin supplements and cod liver oil in pregnancy, vitamin supplements and cod liver oil at 6 mo of age, and for maternal age, maternal atopy, maternal smoking in pregnancy, maternal educational level, postnatal parental smoking, sex, parity, birth weight, season born, breast feeding and type of day care | 7 |

| Granell 200815 | Birth cohort study of 5,364 children in UK, carried out from 1991-1992, embedded in the ALSPAC study; 7-8 yr | Asthma: physician-diagnosed and current symptom Atopy: SPT positive |

Maternal and child MTHFRC677T polymorphism, Maternal and child folate consumption from foods, and maternal folic acid supplement | No significant association between MTHFRC677T genotype and asthma or atopy in mothers or children | No assessment of dietary intake in early pregnancy, and potential selection bias due to loss of follow-up | Exposure to pre-natal and post-natal smoking, maternal education and social class | 7 |

| Litonjua 200616 | Birth cohort of 1,290 children in USA, carried out from 1999-2002, embedded in the Project Viva study; 2 yr | Wheeze: mother-reported symptom Eczema: health care professional diagnosed |

Maternal folate consumption from foods and folic acid supplement | No significant association between maternal folate intake in the first and second trimesters of pregnancy and wheeze or eczema at age 2 yr | Limited assessment of folate status at different stage of pregnancy, and potential selection bias due to loss of follow-up | Sex, maternal age, maternal asthma, paternal asthma, family income, passive smoke exposure, breastfeeding, and other | 8 |

MOCEH, Mothers and Children's Environmental Health study; AD, Atopic dermatitis; BMI, body mass index; MTHFR, methylene-tetrahydrofolate reductase; ISAAC, International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood; COAST, Childhood Origins of Asthma project; AIP, Asthma in Pregnancy; PRAM, Perinatal Risk of Asthma in Infants of Asthmatic Mothers; PIAMA, Prevention and Incidence of Asthma and Mite Allergy; OMCHS, Osaka Maternal and Child Health Study; MoBa, Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study; ALSPAC, Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children

Table S2. The characteristics of included study (case-control study).

| Study | Study Design | Definition of Outcomes | Measurement of Folate/Folic Acid Status | Main Findings | Study Limitations | Adjusted Factors | Quality Assessment Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haberg 201117 | Case-control study of 1,962 children (case/control: 507/1455) in Norway, carried out in 2002-2004, embedded in the MoBa study, and followed up to age 3 yr | Asthma: mother report and had used inhalant medication | Maternal blood plasma folate level | Maternal plasma folate in the second trimester of pregnancy was linearly associated with increased risk of asthma at age 3 yr | Lack of data on dietary intake, and nonassessment of folate status in early pregnancy | Maternal educational level, maternal age, parity, maternal atopy, maternal body mass index, maternal smoking in pregnancy, maternal smoking at age 3 yr, and supplement use at age 3 yr | 7 |

| Farres 201118 | Case-control study of 180 adults (case/control: 120/60) in Egypt, carried out in 2009-2010 | Asthma: doctor-diagnosed, GINA 2007 Atopic: at least one positive SPT |

Serum folate level | No significant association between serum folate levels and asthma or FEV1. Among atopic asthmatics, serum folate levels were inversely associated with total IgE levels, and the number of positive SPTs. | Small sample size, nonassessment of dietary intake, and limited adjustment for potential confounding factors | Age and sex | 6 |

| Bueso 201119 | Case-control study of 169 children (case/control: 93/76) aged 13-14 yr in Norway, carried out in 2005-2006, embedded in the ECA study | Asthma: doctor-diagnosed and/or symptoms and/or medication use, at least fulfilled two of the three criteria | folate consumption from foods and folic acid supplement | No significant association between dietary intake of folate and asthma | Small sample size, and limited adjustment for potential confounding factors | Age and sex | 8 |

| Shaheen 201120 | Case-conrol study of 40 children (case/control: 20/20) in India, carried out in 2009-2010 | AD: physician diagnosed | Serum folic acid level | No significant association between serum folic acid level and AD | Small sample size, lack of data on dietary intake, and lack of adjustment for potential confounding factors | NA | 6 |

| Oh 201021 | Case-control study of 422 children (case/control: 180/242) in Korea, carried out in 2006-2007 | AD: ISAAC | folate consumption from foods and folic acid supplement | Intake of folic acid was inversely associated with AD risk | Lack of data on folate levels, and potential selection bias | Monthly household income, parental histories of allergic diseases, and the child's age, gender, body mass index, supplement intake (ye s/no), and total energy intake | 8 |

| Patel 200622 | Case-control study of 1030 adults (case/control: 515/515) in UK, carried out from 1993-1998, embedded in the EPIC-Norfolk study | Asthma: physician diagnosed | folate consumption from foods | Increased intake of folate was associated with reduced risk of asthma | Nonassessment of folate supplementation | Pack years smoked, social class, BMI, increasing level of physical activity and level of education | 8 |

| Zhou 200323 | Case-control study of 1,682 adults (case/control: 433/1,249) in Japan, carried out in 2001-2002 | Asthma: NA | MTHFRC677T polymorphism | The TT genotype of MTHFRC677T was significant associated with increased risk of atopic asthma | Lack of data on folate levels, lack of clear asthma definition, and lack of adjustment for potential confounding factors | NA | 4 |

MoBa, Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study; GINA, Global Initiative for Asthma; SPT, Skin Prick Test; AD, Atopic dermatitis; EPIC-Norfolk, Norfolk arm of the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer; MTHFR, methylene-tetrahydrofolate reductase.

Table S3. The characteristics of included study (cross-section study).

| Study | Study Design | Definition of outcomes | Measurement of folate/folic acid status | Main Findings | Study Limitations | Adjusted factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thuesen 200924 | Cross-sectional study of 1,207 adults (15-77 yr) in Denmark, carried out in 1997-1998 | Asthma: diagnose of allergic asthma, and self-reported allergy and asthma SPT reactivity: at least one positive SPT sIgE positivity: a positive test to at least one of the six inhalant allergens |

MTHFRC677T polymorphism | No significant associations between MTHFRC677T polymorphism and asthma or allergy | Lack of data on folate levels, and potential selection bias | Sex, age, BMI, smoking, social status and alcohol intake |

| Matsui 200925 | Cross-sectional study of 8,083 individuals (≥2 yr) in USA, collected data from the 2005-2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Wheeze: symptom Atopy: at least 1 positive allergen-specific IgE level |

Asthma: doctor-diagnosed | Serum folate level | Higher serum folate levels were inversely associated with a lower risk of wheeze and atopy, but not with asthma | Nonassessment of the effect with different age group, and lack of data on dietary intake | Age, sex, race/ethnicity, and poverty income ratio |

| Woods 200326 | Cross-sectional study of 1,601 adults in Australia, carried out in 1999 Atopy: a ≥3 mm wheal diameter in response to any allergen in SPT |

Asthma: self-reported or doctor-diagnosed | folate consumption from foods | No consistent associations between intakes of folate and asthma, BHR, or atopy | Potential selection bias | Age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, region of birth, and family history of asthma |

References

- 1.Braman SS. The global burden of asthma. Chest. 2006;130:4S–12S. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1_suppl.4S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong GW, Leung TF, Ko FW. Changing prevalence of allergic diseases in the Asia-pacific region. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2013;5:251–257. doi: 10.4168/aair.2013.5.5.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Depeint F, Bruce WR, Shangari N, Mehta R, O'Brien PJ. Mitochondrial function and toxicity: role of B vitamins on the one-carbon transfer pathways. Chem Biol Interact. 2006;163:113–132. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MRC Vitamin Study Research Group. Prevention of neural tube defects: results of the Medical Research Council Vitamin Study. Lancet. 1991;338:131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Czeizel AE, Dudás I, Paput L, Bánhidy F. Prevention of neural-tube defects with periconceptional folic acid, methylfolate, or multivitamins? Ann Nutr Metab. 2011;58:263–271. doi: 10.1159/000330776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De-Regil LM, Fernández-Gaxiola AC, Dowswell T, Peña-Rosas JP. Effects and safety of periconceptional folate supplementation for preventing birth defects. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD007950. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007950.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hollingsworth JW, Maruoka S, Boon K, Garantziotis S, Li Z, Tomfohr J, et al. In utero supplementation with methyl donors enhances allergic airway disease in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3462–3469. doi: 10.1172/JCI34378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 8.Håberg SE, London SJ, Stigum H, Nafstad P, Nystad W. Folic acid supplements in pregnancy and early childhood respiratory health. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:180–184. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.142448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitrow MJ, Moore VM, Rumbold AR, Davies MJ. Effect of supplemental folic acid in pregnancy on childhood asthma: a prospective birth cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170:1486–1493. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinussen MP, Risnes KR, Jacobsen GW, Bracken MB. Folic acid supplementation in early pregnancy and asthma in children aged 6 years. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:72.e1–72.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bekkers MB, Elstgeest LE, Scholtens S, Haveman-Nies A, de Jongste JC, Kerkhof M, et al. Maternal use of folic acid supplements during pregnancy, and childhood respiratory health and atopy. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:1468–1474. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00094511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magdelijns FJ, Mommers M, Penders J, Smits L, Thijs C. Folic acid use in pregnancy and the development of atopy, asthma, and lung function in childhood. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e135–e144. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiefte-de Jong JC, Timmermans S, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Tiemeier H, Steegers EA, et al. High circulating folate and vitamin B-12 concentrations in women during pregnancy are associated with increased prevalence of atopic dermatitis in their offspring. J Nutr. 2012;142:731–738. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.154948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Husemoen LL, Toft U, Fenger M, Jørgensen T, Johansen N, Linneberg A. The association between atopy and factors influencing folate metabolism: is low folate status causally related to the development of atopy? Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:954–961. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thuesen BH, Husemoen LL, Fenger M, Linneberg A. Lack of association between the MTHFR (C677T) polymorphism and atopic disease. Clin Respir J. 2009;3:102–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-699X.2009.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blatter J, Han YY, Forno E, Brehm J, Bodnar L, Celedón JC. Folate and asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:12–17. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201302-0317PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharland E, Montgomery B, Granell R. Folic acid in pregnancy - is there a link with childhood asthma or wheeze? Aust Fam Physician. 2011;40:421–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crider KS, Cordero AM, Qi YP, Mulinare J, Dowling NF, Berry RJ. Prenatal folic acid and risk of asthma in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98:1272–1281. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.065623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown SB, Reeves KW, Bertone-Johnson ER. Maternal folate exposure in pregnancy and childhood asthma and allergy: a systematic review. Nutr Rev. 2014;72:55–64. doi: 10.1111/nure.12080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thuesen BH, Husemoen LL, Ovesen L, Jørgensen T, Fenger M, Gilderson G, et al. Atopy, asthma, and lung function in relation to folate and vitamin B(12) in adults. Allergy. 2010;65:1446–1454. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brozek J, Oxman A, Schünemann H The GRADE Working Group. GRADEpro. Version 3.6 for Windows [Computer Program] Hamilton: McMaster University; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyake Y, Sasaki S, Tanaka K, Hirota Y. Maternal B vitamin intake during pregnancy and wheeze and eczema in Japanese infants aged 16-24 months: the Osaka Maternal and Child Health Study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011;22:69–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oh SY, Chung J, Kim MK, Kwon SO, Cho BH. Antioxidant nutrient intakes and corresponding biomarkers associated with the risk of atopic dermatitis in young children. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64:245–252. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2009.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Håberg SE, London SJ, Nafstad P, Nilsen RM, Ueland PM, Vollset SE, et al. Maternal folate levels in pregnancy and asthma in children at age 3 years. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:262–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Granell R, Heron J, Lewis S, Davey Smith G, Sterne JA, Henderson J. The association between mother and child MTHFR C677T polymorphisms, dietary folate intake and childhood atopy in a population-based, longitudinal birth cohort. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:320–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bueso AK, Berntsen S, Mowinckel P, Andersen LF, Lødrup Carlsen KC, Carlsen KH. Dietary intake in adolescents with asthma--potential for improvement. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011;22:19–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farres MN, Shahin RY, Melek NA, El-Kabarity RH, Arafa NA. Study of folate status among Egyptian asthmatics. Intern Med. 2011;50:205–211. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.50.4424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsui EC, Matsui W. Higher serum folate levels are associated with a lower risk of atopy and wheeze. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1253–1259.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunstan JA, West C, McCarthy S, Metcalfe J, Meldrum S, Oddy WH, et al. The relationship between maternal folate status in pregnancy, cord blood folate levels, and allergic outcomes in early childhood. Allergy. 2012;67:50–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaheen MA, Attia EA, Louka ML, Bareedy N. Study of the role of serum folic acid in atopic dermatitis: a correlation with serum IgE and disease severity. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:673–677. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.91827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou CC, Tang LF, Jiang MZ, Zhao ZY, Hirokazu T, Mitsufumi M. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase [correction of reducatase] polymorphism and asthma. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2003;26:161–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Valk RJ, Kiefte-de Jong JC, Sonnenschein-van der Voort AM, Duijts L, Hafkamp-de Groen E, Moll HA, et al. Neonatal folate, homocysteine, vitamin B12 levels and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase variants in childhood asthma and eczema. Allergy. 2013;68:788–795. doi: 10.1111/all.12146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okupa AY, Lemanske RF, Jr, Jackson DJ, Evans MD, Wood RA, Matsui EC. Early-life folate levels are associated with incident allergic sensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:226–228.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin JH, Matsui W, Aloe C, Peng RD, Diette GB, Breysse PN, et al. Relationships between folate and inflammatory features of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:918–920. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nwaru BI, Erkkola M, Ahonen S, Kaila M, Kronberg-Kippilä C, Ilonen J, et al. Intake of antioxidants during pregnancy and the risk of allergies and asthma in the offspring. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65:937–943. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2011.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Litonjua AA, Rifas-Shiman SL, Ly NP, Tantisira KG, Rich-Edwards JW, Camargo CA, Jr, et al. Maternal antioxidant intake in pregnancy and wheezing illnesses in children at 2 y of age. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:903–911. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.4.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patel BD, Welch AA, Bingham SA, Luben RN, Day NE, Khaw KT, et al. Dietary antioxidants and asthma in adults. Thorax. 2006;61:388–393. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.024935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woods RK, Walters EH, Raven JM, Wolfe R, Ireland PD, Thien FC, et al. Food and nutrient intakes and asthma risk in young adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:414–421. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.3.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim JH, Jeong KS, Ha EH, Park H, Ha M, Hong YC, et al. Relationship between prenatal and postnatal exposures to folate and risks of allergic and respiratory diseases in early childhood. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2015;50:155–163. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang G, Khoo SK, Mäkelä MJ, Candelaria P, Hayden CM, von Hertzen L, et al. Maternal genetic variants of IL4/IL13 pathway genes on IgE with "Western or Eastern Environments/Lifestyles". Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2014;6:350–356. doi: 10.4168/aair.2014.6.4.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. The characteristics of studies included in the systematic review on the relationship between folate status and asthma, wheeze or other allergic diseases (cohort study).

| Study | Study Design; follow-up time | Definition of Outcomes | Measurement of Folate/Folic Acid Status | Main Findings | Study Limitations | Adjusted Factors | Quality Assessment Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim 20141 | Birth cohort study of 917 children in South Korea, carried out from 2006-2011, embed in the MOCEH study; 2 yr | Asthma: physician-diagnosed or treatment for asthma in past year AD: physician-diagnosed or treatment for AD in past year |

Serum folate level | Increased maternal folate level during mid-pregnancy was associated with a decreased risk of LRTIs at 6 mo and AD at 24 mo | Potential selection bias due to the substantial loss of follow-up (~50%) at 24 mo, no assessment of maternal folate status in the early pregnancy | Baby's sex, birth weight, gestational age, and duration of breastfeeding, and maternal age, the history of allergic diseases such as AD, asthma, allergic rhinitis, and allergic conjunctivitis, the urinary cotinine levels in mid- and late-pregnancy, and the prepregnancy, BMI | 7 |

| van der Valk 20132 | Birth cohort study of 2001 children in Netherlands, carried out from 2002-2006, embedded in the Generation R study; 6 yr | Asthma: physician-diagnosed Wheeze: using questions from the ISAAC Eczema: physician-diagnosed or self-reported |

Cord blood folate, MTHFRC677T polymorphism | No significant association between folate level at birth and wheeze or eczema until 4 yr, or asthma and eczema ever. Genetic mutations in MTHFRC677T and higher folate levels were associated with increased risk of eczema until 4 yr | Lack of data on maternal folate status, potential selection bias due to missing cord blood samples | Maternal age, BMI, educational level at intake, history of maternal atopy or asthma, parity, smoking, folic acid supplement use and pet keeping during pregnancy, and children's sex, gestational age, birth weight and day care attendance, based on the significance of their associations with repeated wheezing (P < 0.05), or a change in effect estimate of > 10% | 8 |

| Okupa 20133 | Cohort study of 138 children (2-9 yr) in USA, carried out from 1998, embedded in the COAST study; 8 yr | Asthma: physician-diagnosed and/or the use of asthma medication Sensitization: 1 or more positive (>0.34) specific IgE results |

Plasma folate level | Higher plasma folate levels at or before age 6 yr were associated with allergic sensitization but not with IgE production, wheeze, or asthma at age 6 yr | Small sample size, no assessment of dietary intake, and limited adjustment for covariates | Gender and socioeconomic status | 6 |

| Lin 20134 | Cohort study of 150 children (5-17 yr) in USA; 1 yr | Asthma: long-term controller medication for asthma or meeting National Asthma Education and Prevention Program guideline Atopy: at least 1 positive skin prick test (SPT) result |

Serum folate level | Serum folate level was not significantly associated with FENO, the number of positive SPTs, lung function, or hospitalizations for asthma. A folate level in the second quartile was associated with increased total IgE when compared with the lowest folate level. Increased serum folate level was associated with less exercise-related symptoms | Small sample size, no assessment of dietary intake, lack of multiple testing corrections, and limited adjustment for covariates | Age, sex, and education | 6 |

| Martinussen 20125 | Birth cohort study of 1,499 children in USA, carried out from 1997-2000, embedded in the AIP and later the PRAM study; 6 yr | Asthma: physician diagnosed and current symptoms | Maternal folic acid supplement | No significant association between maternal folate supplement in the first trimester and childhood asthma at 6 age yr | Lake of date on maternal dietary intake | Maternal marital status, family income, and maternal asthma. | 9 |

| Bekkers 20126 | Birth cohort of 3,786 children in Netherlands, carried out from 1996-1997, embedded in the PIAMA study; 8 yr | Asthma: symptoms and/or doctor-diagnosed Wheeze: at least one attack of wheeze Eczema: an itchy rash that came and went on typical eczema sites Sensitization: serum IgE ≥0.70 IU/mL-1 |

Maternal folic acid supplement | Maternal folic acid use was associated with wheeze at age 1 yr and eczema at age 7 yr. No overall (from 1 to 8 yr of age) associations between maternal folic acid supplementation and (frequent) asthma symptoms, wheeze, LRIs and eczema | Lack of data on maternal dietary intake | Maternal education, maternal allergy, maternal smoking during pregnancy and number of older siblings | 9 |

| Kiefte-de 20127 | Birth cohort study of 8,742 children in Netherlands, carried out from 2002-2006, embedded in the Generation R study; 4 yr | Wheeze: symptoms, ISAAC AD: doctor-diagnosed |

Maternal MTHFR C677T polymorphism, maternal folic acid supplement, and maternal plasma folate | Higher maternal plasma folate level in early pregnancy was associated with increased prevalence of AD but not with wheeze and shortness of breath at age 4 yr | No assessment of maternal dietary intake, and measured plasma folate level at a very early stage in pregnancy (13±2.0 wk of gestation) | Time, maternal ethnicity, parental atopic constitution, parity, maternal BMI, maternal age, breastfeeding duration, daycare attendance, maternal educational level, maternal smoking and alcohol consumption, and fetal gender and birth weight SD score derived from generalized estimation equations. | 8 |

| Dunstan 2012 8 | Birth cohort of 484 children in Australia; 1 yr | Asthma: recurrent wheeze to be responsive to bronchodilator medications Eczema: typical skin lesions Food Allergy: IgE-mediated food allergy and a positive SPT to the implicated food Sensitization: SPT positive |

Folate consumption from foods and folic acid supplement, maternal and cord blood serum folate level | Maternal folate taken as a supplement in higher doses during the third trimester was significant associated with eczema at age 1 yr. With cord folate levels <50 nmol/L and >75 nmol/L was associated with greater sensitization risk than levels between 50 and 75 nmol/L | Short duration of follow-up and limited adjustment of covariates | Maternal allergy and infant postnatal diet | 6 |

| Magdelijns 20119 | Birth cohort of 2,640 children in Netherlands, carried out from 2000, embedded in the KOALA Birth Cohort Study; 6-7 yr | Asthma: physician-diagnosed with clinical symptoms and/or asthma medication use Wheeze: parents report Eczema: parents report AD: symptoms, UK Working Party criteria Sensitization: sIgE >0.3 IU/mL for ≥1 of the tested allergens |

Maternal folic acid supplement and intracellular folic acid level | No significant association between maternal folic acid supplement use during pregnancy and AD and sensitization at age 2 yr, or wheeze, lung function, asthma, and eczema at age 6-7 yr. Maternal folate level in erythrocytes in late pregnancy was inversely associated with asthma at age 6-7 yr.] (P=0.05) | No assessment of maternal dietary intake, potential selection bias due to loss of follow-up, and no assessment of folate level in early pregnancy | Maternal antibiotic use during pregnancy, maternal smoking during pregnancy, maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy, mode and place of delivery, birthweight, gender of the child, treatment with antibiotics during the first 6 mo of life, breastfeeding during the first 2 yr of life, exposure to domestic animals during pregnancy and the first 2 yr of life, exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in the first 6 to 7 yr of life, siblings, family history, recruitment group, maternal education level, daycare, and other supplement use during pregnancy. | 8 |

| Nwaru 201110 | Birth cohort of 2,441 children in Finland, carried out from 1996-1997, embedded in the Finnish Type 1 Diabetes Prediction and Prevention study; 5 yr | Asthma: physician-diagnosed plus either any wheezing symptom or asthma medication use in the past 12 mo, ISAAC Eczema: parents report |

Maternal folate consumption from foods and folic acid supplement | No significant associations between maternal folate intake and eczema at age 5 yr | Potential recall bias | Sex of child, place of birth, season of birth, gestational age at birth, maternal age at birth, maternal basic education, maternal smoking during pregnancy, mode of delivery, number of siblings, parental asthma, parental allergic rhinitis, pets at home at 1 yr of age, and atopic eczema by 6 mo of age. | 9 |

| Miyake 201111 | Birth cohort of 763 children in Japan, carried out from 2001-2003, embedded in the OMCHS study; 16-24 mo | Wheeze: had symptom 12 mo pre based on the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) criteria Eczema: had symptom, ISAAC |

Maternal folate consumption from foods | No significant association between maternal consumption of folate during pregnancy and wheeze or eczema at age 16-24 mo | No assessment of maternal folate supplementation, lack of analysis of folate intake at different stage of pregnancy, and potential selection bias | Maternal age, gestation at baseline, residential municipality at baseline, family income, maternal and paternal education, maternal and paternal history of asthma, atopic eczema, and allergic rhinitis, changes in maternal diet in the previous 1 mo, season when data at baseline were collected, maternal smoking during pregnancy, baby's older siblings, baby's sex, baby's birth weight, household smoking in same room as infant, breastfeeding duration, age at which solid foods were introduced, age of infant at the third survey, and maternal intake of docosahexaenoic acid, n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids, vitamin D, calcium, vitamin E, and b-carotene during pregnancy. | 8 |

| Thuesen 201012 | Cohort study of 6,784 adults (30-60 yr) in Denmark, carried out from 1999-2001, embedded in the Inter99 study; 5 yr | Asthma: self-reported doctor-diagnosed Atopy: specific IgE ≥0.35kU/l to at least one of the four allergens |

Dietary intake of folate, serum folate level and MTHFRC677T polymorphism | Low serum folate level and the TT genotype of the MTHFR-C677T polymorphism were associated with increased prevalence of self-reported doctor-diagnosed asthma at baseline | Lake of data on vitamin supplements, limited analysis of longitudinal data with 5-yr follow-up, and potential bias due to loss of follow-up | Age, sex, total energy intake, smoking, alcohol intake, BMI, and socioeconomic status | 7 |

| Whitrow 200913 | Birth cohort study of 557 children in Australia, carried out from 1998-2000, embedded in the Generation 1 cohort study; 5.5 yr | Asthma: physician-diagnosed | Maternal folate consumption from foods and folic acid supplement | Maternal folic acid supplementation in late pregnancy significantly increase the risk of asthma 3.5 yr and of persistent asthma at 3.5 and 5.5 yr | No assessment of folate level, and potential selection bias due to loss of follow-up | Maternal education, maternal age, parity, gravida, gestational age, maternal asthma status, and breastfeeding (partial or full for <3 mo) | 9 |

| Haberg 200914 | Birth cohort study of 32,077 children in Norway, carried out from 2000-2005, embedded in the MoBa study; 1.5 yr | Wheeze: had symptom | Maternal folic acid supplement | Maternal folate supplementation in the first trimester was associated with increased risk of wheeze and LRI up to 18 mo of age | No assessment of dietary intake | Other vitamin supplements and cod liver oil in pregnancy, vitamin supplements and cod liver oil at 6 mo of age, and for maternal age, maternal atopy, maternal smoking in pregnancy, maternal educational level, postnatal parental smoking, sex, parity, birth weight, season born, breast feeding and type of day care | 7 |

| Granell 200815 | Birth cohort study of 5,364 children in UK, carried out from 1991-1992, embedded in the ALSPAC study; 7-8 yr | Asthma: physician-diagnosed and current symptom Atopy: SPT positive |

Maternal and child MTHFRC677T polymorphism, Maternal and child folate consumption from foods, and maternal folic acid supplement | No significant association between MTHFRC677T genotype and asthma or atopy in mothers or children | No assessment of dietary intake in early pregnancy, and potential selection bias due to loss of follow-up | Exposure to pre-natal and post-natal smoking, maternal education and social class | 7 |

| Litonjua 200616 | Birth cohort of 1,290 children in USA, carried out from 1999-2002, embedded in the Project Viva study; 2 yr | Wheeze: mother-reported symptom Eczema: health care professional diagnosed |

Maternal folate consumption from foods and folic acid supplement | No significant association between maternal folate intake in the first and second trimesters of pregnancy and wheeze or eczema at age 2 yr | Limited assessment of folate status at different stage of pregnancy, and potential selection bias due to loss of follow-up | Sex, maternal age, maternal asthma, paternal asthma, family income, passive smoke exposure, breastfeeding, and other | 8 |

MOCEH, Mothers and Children's Environmental Health study; AD, Atopic dermatitis; BMI, body mass index; MTHFR, methylene-tetrahydrofolate reductase; ISAAC, International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood; COAST, Childhood Origins of Asthma project; AIP, Asthma in Pregnancy; PRAM, Perinatal Risk of Asthma in Infants of Asthmatic Mothers; PIAMA, Prevention and Incidence of Asthma and Mite Allergy; OMCHS, Osaka Maternal and Child Health Study; MoBa, Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study; ALSPAC, Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children

Table S2. The characteristics of included study (case-control study).

| Study | Study Design | Definition of Outcomes | Measurement of Folate/Folic Acid Status | Main Findings | Study Limitations | Adjusted Factors | Quality Assessment Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haberg 201117 | Case-control study of 1,962 children (case/control: 507/1455) in Norway, carried out in 2002-2004, embedded in the MoBa study, and followed up to age 3 yr | Asthma: mother report and had used inhalant medication | Maternal blood plasma folate level | Maternal plasma folate in the second trimester of pregnancy was linearly associated with increased risk of asthma at age 3 yr | Lack of data on dietary intake, and nonassessment of folate status in early pregnancy | Maternal educational level, maternal age, parity, maternal atopy, maternal body mass index, maternal smoking in pregnancy, maternal smoking at age 3 yr, and supplement use at age 3 yr | 7 |

| Farres 201118 | Case-control study of 180 adults (case/control: 120/60) in Egypt, carried out in 2009-2010 | Asthma: doctor-diagnosed, GINA 2007 Atopic: at least one positive SPT |

Serum folate level | No significant association between serum folate levels and asthma or FEV1. Among atopic asthmatics, serum folate levels were inversely associated with total IgE levels, and the number of positive SPTs. | Small sample size, nonassessment of dietary intake, and limited adjustment for potential confounding factors | Age and sex | 6 |

| Bueso 201119 | Case-control study of 169 children (case/control: 93/76) aged 13-14 yr in Norway, carried out in 2005-2006, embedded in the ECA study | Asthma: doctor-diagnosed and/or symptoms and/or medication use, at least fulfilled two of the three criteria | folate consumption from foods and folic acid supplement | No significant association between dietary intake of folate and asthma | Small sample size, and limited adjustment for potential confounding factors | Age and sex | 8 |

| Shaheen 201120 | Case-conrol study of 40 children (case/control: 20/20) in India, carried out in 2009-2010 | AD: physician diagnosed | Serum folic acid level | No significant association between serum folic acid level and AD | Small sample size, lack of data on dietary intake, and lack of adjustment for potential confounding factors | NA | 6 |