Abstract

Recent breakthrough studies documented consistent activation of specific endogenous retroviruses in human embryonic stem cells and preimplantation human embryos and demonstrated the essential role of the sustained retroviral activities for maintenance of pluripotency and embryonic stem cell identity. Present analysis has led to the hypothesis that activation of the human stem cell-associated retroviruses (SCARs), namely LTR7/HERVH and LTR5_Hs/HERVK, is likely associated with the emergence of clinically lethal therapy resistant death-from-cancer phenotypes in a sub-set of cancer patients diagnosed with different types of malignant tumors.

Keywords: human-specific regulatory sequences, human ESC, LTR7/HERVH, LTR5HS/HERVK, therapy-resistant cancers

In human cells, retrotransposons' activity is believed to be suppressed to restrict the potentially harmful effects of mutations on functional genome integrity and to ensure the maintenance of genomic stability. Human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and human embryos seem markedly different in this regard. In recent years, multiple reports demonstrate that retrotransposons' activity is markedly enhanced in hESC and human embryos and most active transposable elements (TEs) may be found among human endogenous retroviruses (HERV). Kunarso et al. [1] identified LTR7/HERVH as one of the most over-represented TEs seeding NANOG and POU5F1 binding sites throughout the human genome. HERV subfamily H (HERVH) RNA expression is markedly increased in hESCs [2, 3], and an enhanced rate of insertion of LTR7/HERVH sequences appears to be associated with binding sites for pluripotency core transcription factors [1, 2, 4] and long noncoding RNAs [5]. Expression of HERVH appears regulated by the pluripotency regulatory circuitry since 80% of long terminal repeats (LTRs) of the 50 most highly expressed HERVH are occupied by pluripotency core transcription factors, including NANOG and POU5F1 [2]. Furthermore, TE-derived sequences, most notably LTR7/HERVH, LTR5_Hs/HERVK, and L1HS, harbor 99.8% of the candidate human-specific regulatory loci (HSRL) with putative transcription factor-binding sites (TFBS) in the hESC genome [4].

The LTR7 subfamily is rapidly demethylated and upregulated in the blastocyst of human embryos and remains highly expressed in human ES cells [6]. In human ESC and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC), LTR7 sequences harboring the promoter for the downstream full-length HERVH-int elements, as well as LTR7B and LTR7Y sequences, were expressed at the highest levels and were the most statistically significantly up-regulated retrotransposons in human stem cells [7]. LTRs of HERVH, in particular, LTR7, function in hESC as enhancers and HERVH sequences encode nuclear non-coding RNAs, which are required for maintenance of pluripotency and identity of hESC [8]. Transient hyper activation of HERVH is required for reprogramming of human cells toward induced pluripotent stem cells, maintenance of pluripotency and reestablishment of differentiation potential [9]. Failure to control the LTR7/HERVH activity leads to the differentiation-defective phenotype in neural lineage [9, 10]. The continuing activity of L1 retrotransposons may be relevant as well because significant activities of both L1 transcription and transposition were recently reported in humans and other great apes [11] and L1HS was implicated in the creation of human-specific TFBS in the hESC genome [4].

Single-cell RNA sequencing of human preimplantation embryos and embryonic stem cells [12, 13] facilitated identification of specific distinct populations of early human embryonic stem cells, which were defined by distinct patterns of marked activation of specific retroviral elements [14]. Consistent with definition of increased LTR7/HERVH expression as a hallmark of naive-like hESCs, a sub-population of hESCs and human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) manifesting key properties of naive-like pluripotent stem cells can be genetically tagged and successfully isolated based on elevated transcription of LTR7/HERVH [15]. Targeted interference with HERVH activity and HERVH-derived transcripts severely compromises self-renewal functions [15]. Transactivation of LTR5_Hs/HERVK by pluripotency master transcription factor POU5F1 (OCT4) at hypomethylated long terminal repeat elements (LTRs), which represent the most recent genomic integration sites of HERVK retroviruses, induces HERVK expression during normal human embryogenesis, beginning with embryonic genome activation at the eight-cell stage, continuing through the stage of epiblast cells in preimplantation blastocysts, and ceasing during hESC derivation from blastocyst outgrowths [16]. Grow et al. [16] reported unequivocal experimental evidence demonstrating the presence of HERVK viral-like particles and Gag proteins in human blastocysts, consistent with the idea that endogenous human retroviruses are functionally active during early human embryonic development.

Significantly, expression of HERVH-encoded long noncoding RNAs (lnc-RNAs) is required for maintenance of pluripotency and hESC identity [8]. In human ESC, 128 LTR7/HERVH loci with markedly increased transcription were identified [8]. It has been suggested that these genomic loci represent the most likely functional candidates from the LTR7/HERVH family playing critical regulatory roles in maintenance of pluripotency and transition to differentiation phenotypes in humans [4]. Conservation analysis of the 128 LTR7/HERVH loci with the most prominent expression in hESC demonstrates that none of them are present in Neanderthals genome, whereas 109 loci (85%) are shared with Chimpanzee [4]. Considering that Neanderthals' genomes are ~40,000 years old and Chimpanzee's genome is contemporary, these results are in agreement with the hypothesis that LTR7/HERVH viruses were integrated at these sites in genomes of primates' population very recently. Distinct patterns of expression of different sub-sets of transcripts selected from 128 LTR7/HERVH loci hyperactive in hESC are readily detectable in adult human tissues, including various regions of human brain [4]. These observations support the idea that sustained LTR7/HERVH activity may be relevant to physiological functions of human embryos and adult human organs, specifically human brain.

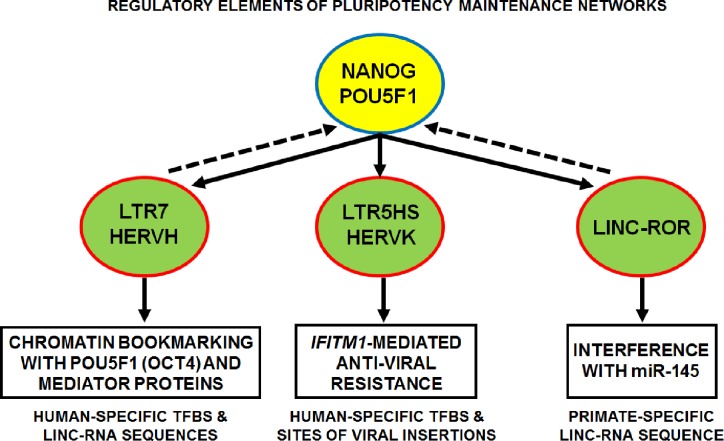

Taken together, these breakthrough experiments conclusively established the essential role of the sustained, tightly controlled in the temporal-spatial fashion activity of specific endogenous retroviruses for pluripotency maintenance and functional identity of human pluripotent stem cells, including hESC and iPSC (Figure 1). Is this true for cancer stem cells as well and activation of human stem cell-associated retroviruses (SCARs) occurs in malignant tumors? Activation of the stemness genomic networks in human malignant tumors was linked with the emergence of clinically-lethal death-from cancer phenotypes in cancer patients, which are consistently associated with significantly increased likelihood of therapy failure, disease recurrence, and development of distant metastasis [17-26]. Gene expression signatures of the hESC genomic circuitry successfully identified therapy-resistant tumors in cancer patients diagnosed with multiple types of epithelial tumors [25, 26]. Since these genotype/phenotype relationships between activation of stemness genomic networks and clinically-lethal therapy-resistant phenotypes of human cancers are readily detectable in the early-stage tumors from cancer patients diagnosed with multiple types of malignancies [17-26], it seems likely to expect that emergence of these tumors may be triggered by (or associated with) activation of endogenous human SCARs in cancer stem cells. One of the key molecular mechanisms of SCARs-mediated reprogramming of genomic regulatory networks is likely associated with functions of SCARs-derived long noncoding RNAs and human-specific TFBS (Figure 1). Consistent with this idea, recent experimental evidence revealing the mechanistic role in human cancer development of one of the LTR7/HERVH-derived long noncoding RNAs, namely linc-RNA-ROR [5, 27, 28], are beginning to emerge [29-33]. Comprehensive catalogues of transcriptionally active SCARs [8, 12-16], chimeric transcripts [14-16], and human-specific TFBS in the hESC genome [4] should greatly facilitate the follow-up mechanistic studies of human cancer. Collectively, these findings instantly open exciting new diagnostic and therapeutic opportunities for individualized targeted experimental and clinical interventions aiming at early detection and eradication of clinically-lethal sub-sets of malignant tumors in cancer patients.

Figure 1. Regulatory elements of pluripotency maintenance networks driven by sustained activity of endogenous human stem cell-associated retroviruses (SCARs).

See text for further details and references. TFBS, transcription factor-binding sites; linc-RNA, long intergenic noncoding RNA; lnc-RNAs, long noncoding RNAs.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest associated with this publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kunarso G, Chia NY, Jeyakani J, Hwang C, Lu X, Chan YS, Ng HH, Bourque G. Transposable elements have rewired the core regulatory network of human embryonic stem cells. Nat Genet. 2010;42:631–634. doi: 10.1038/ng.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santoni FA, Guerra J, Luban J. HERV-H RNA is abundant in human embryonic stem cells and a precise marker for pluripotency. Retrovirology. 2012;9:111. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-9-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xie W, Schultz MD, Lister R, Hou Z, Rajagopal N, Ray P, Whitaker JW, Tian S, Hawkins RD, Leung D, Yang H, Wang T, Lee AY, et al. Epigenomic analysis of multilineage differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2013;153:1134–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glinsky GV. Transposable Elements and DNA Methylation Create in Embryonic Stem Cells Human-Specific Regulatory Sequences Associated with Distal Enhancers and Noncoding RNAs. Genome Biol Evol. 2015;7:1432–54. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelley D, Rinn J. Transposable elements reveal a stem cell-specific class of long noncoding RNAs. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R107. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-11-r107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith ZD, Chan MM, Humm KC, Karnik R, Mekhoubad S, Regev A, Eggan K, Meissner A. DNA methylation dynamics of the human preimplantation embryo. Nature. 2014;511:611–615. doi: 10.1038/nature13581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fort A, Hashimoto K, Yamada D, Salimullah M, Keya CA, Saxena A, Bonetti A, Voineagu I, Bertin N, Kratz A, Noro Y, Wong CH, de Hoon M, et al. Deep transcriptome profiling of mammalian stem cells supports a regulatory role for retrotransposons in pluripotency maintenance. Nature Genet. 2014;46:558–566. doi: 10.1038/ng.2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu X, Sachs F, Ramsay L, Jacques PÉ, Göke J, Bourque G, Ng HH. The retrovirus HERVH is a long noncoding RNA required for human embryonic stem cell identity. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:423–425. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohnuki M, Tanabe K1, Sutou K, Teramoto I, Sawamura Y, Narita M, Nakamura M, Tokunaga Y, Nakamura M, Watanabe A, Yamanaka S, Takahashi K. Dynamic regulation of human endogenous retroviruses mediates factor-induced reprogramming and differentiation potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:12426–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413299111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koyanagi-Aoi M, Ohnuki M, Takahashi K, Okita K, Noma H, Sawamura Y, Teramoto I, Narita M, Sato Y, Ichisaka T, Amano N, Watanabe A, Morizane A, Yamada Y, Sato T, Takahashi J, Yamanaka S. Differentiation-defective phenotypes revealed by large-scale analyses of human pluripotent stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:20569–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319061110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marchetto MC, Narvaiza I, Denli AM, Benner C, Lazzarini TA, Nathanson JL, Paquola AC, Desai KN, Herai RH, Weitzman MD, Yeo GW, Muotri AR, Gage FH. Differential LINE-1 regulation in pluripotent stem cells of humans and other great apes. Nature. 2013;503:525–529. doi: 10.1038/nature12686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xue Z, Huang K, Cai C, Cai L, Jiang CY, Feng Y, Liu Z, Zeng Q, Cheng L, Sun YE, Liu JY, Horvath S, Fan G. Genetic programs in human and mouse early embryos revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Nature. 2013;500:593–597. doi: 10.1038/nature12364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan L, Yang M, Guo H, Yang L, Wu J, Li R, Liu P, Lian Y, Zheng X, Yan J, Huang J, Li M, Wu X, Wen L, Lao K, Li R, Qiao J, Tang F. Single-cell RNA-Seq profiling of human preimplantation embryos and embryonic stem cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:1131–1139. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goke J, Lu X, Chan YS, Ng HH, Ly LH, Sachs F, Szczerbinska I. Dynamic transcription of distinct classes of endogenous retroviral elements marks specific populations of early human embryonic cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang J, Xie G, Singh M, Ghanbarian AT, Raskó T, Szvetnik A, Cai H, Besser D, Prigione A, Fuchs NV, Schumann GG, Chen W, Lorincz MC, et al. Primate-specific endogenous retrovirus-driven transcription defines naive-like stem cells. Nature. 2014;516:405–9. doi: 10.1038/nature13804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grow EJ, Flynn RA, Chavez SL3, Bayless NL, Wossidlo M, Wesche DJ, Martin L, Ware CB, Blish CA, Chang HY, Pera RA, Wysocka J. Intrinsic retroviral reactivation in human preimplantation embryos and pluripotent cells. Nature. 2015;522:221–5. doi: 10.1038/nature14308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glinsky GV, Glinskii AB, Stephenson AJ, Hoffman RM, Gerald WL. Expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2004;113:913–923. doi: 10.1172/JCI20032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glinsky GV, Higashiyama T, Glinskii AB. Classification of human breast cancer using gene expression profiling as a component of the survival predictor algorithm. Clinical Cancer Res. 2004;10:2272–2283. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glinsky GV, Glinskii AB, Berezovskaya O. Microarray analysis identifies a death-from-cancer signature predicting therapy failure in patients with multiple types of cancer. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005;115:1503–1521. doi: 10.1172/JCI23412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glinsky GV. Death-from-cancer signatures and stem cell contribution to metastatic cancer. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1171–1175. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.9.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glinsky GV. Genomic models of metastatic cancer: Functional analysis of death-from-cancer signature genes reveals aneuploid, anoikis-resistant, metastasis-enabling phenotype with altered cell cycle control and activated Polycomb Group (PcG) protein chromatin silencing pathway. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1208–1216. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.11.2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berezovska OP, Glinskii AB, Yang Z, Li X-M, Hoffman RM, Glinsky GV. Essential role of the Polycomb Group (PcG) protein chromatin silencing pathway in metastatic prostate cancer. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1886–1901. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.16.3222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glinsky GV. Stem Cell Origin of Death-from-Cancer Phenotypes of Human Prostate and Breast Cancers. Stem Cells Reviews. 2007;3:79–93. doi: 10.1007/s12015-007-0011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glinsky GV. Stemness” genomics law governs clinical behavior of human cancer: Implications for decision making in disease management. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:2846–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glinsky GV, Berezovska O, Glinskii A. Genetic signatures of regulatory circuitry of embryonic stem cells (ESC) identify therapy-resistant phenotypes in cancer patients diagnosed with multiple types of epithelial malignancies. Cancer Research. 2007;67(9 Supplement):1272. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glinskii A, Berezovskaya O, Sidorenko A, Glinsky G. Stemness pathways define therapy-resistant phenotypes of human cancers. Clinical Cancer Research. 2008;14(15 Supplement):B38. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loewer S, Cabili MN, Guttman M, Loh YH, Thomas K, Park IH, Garber M, Curran M, Onder T, Agarwal S, Manos PD, Datta S, Lander ES, et al. Large intergenic non-coding RNA-RoR modulates reprogramming of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1113–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y, Xu Z, Jiang J, Xu C, Kang J, Xiao L, Wu M, Xiong J, Guo X, Liu H. Endogenous miRNA sponge lincRNA-RoR regulates Oct4, Nanog, and Sox2 in human embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Dev Cell. 2013;25:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou X, Gao Q, Wang J, Zhang X, Liu K, Duan Z. Linc-RNA-RoR acts as a “sponge” against mediation of the differentiation of endometrial cancer stem cells by microRNA-145. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;133:333–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hou P, Zhao Y, Li Z, Yao R, Ma M, Gao Y, Zhao L, Zhang Y, Huang B, Lu J. LincRNA-ROR induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and contributes to breast cancer tumorigenesis and metastasis. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1287. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eades G, Wolfson B, Zhang Y, Li Q, Yao Y, Zhou Q. LincRNA-RoR and miR-145 regulate invasion in triple-negative breast cancer via targeting ARF6. Mol Cancer Res. 2015;13:330–8. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feng S, Yao J, Chen Y, Geng P, Zhang H, Ma X, Zhao J, Yu X. Expression and Functional Role of Reprogramming-Related Long Noncoding RNA (lincRNA-ROR) in Glioma. J Mol Neurosci. 2015;56:623–30. doi: 10.1007/s12031-014-0488-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang A, Zhou N, Huang J, Liu Q, Fukuda K, Ma D, Lu Z, Bai C, Watabe K, Mo YY. The human long non-coding RNA-RoR is a p53 repressor in response to DNA damage. Cell Res. 2013;23:340–50. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]