Abstract

Objectives

Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) from a pathophysiological perspective connects various pathways that affect the prognosis after myocardial infarction. The objective was to evaluate the benefits of measuring NGAL for prognostic stratification in addition to the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) score, and to compare it with the prognostic value of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP).

Design

Prospective observational cohort study.

Setting

One university/tertiary centre.

Participants

A total of 673 patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction were treated by primary percutaneous coronary intervention. NGAL and BNP were assessed on hospital admission.

Outcomes

Primary outcome: 1-year mortality. Secondary outcomes: 1-year hospitalisation due to acute heart failure, unplanned revascularisation, reinfarction, stroke and combined end point of 1-year mortality and hospitalisation due to heart failure.

Statistical methods

Using the c-statistic, the ability of NGAL, BNP and TIMI score to predict 1-year mortality alone and in combination with readmission for heart failure was evaluated. The addition of the predictive value of biomarkers to the score was assessed by category free net reclassification improvement (cfNRI) and the integrated discrimination index (IDI).

Results

The NGAL level was significantly higher in non-survivors (67 vs 115 pg/mL; p<0.001). The area under the curve (AUC) values for mortality prediction for NGAL, BNP and TIMI score were 75.5, 78.7 and 74.4, respectively (all p<0.001) with optimal cut-off values of 84 pg/mL for NGAL and 150 pg/mL for BNP. The addition of NGAL and BNP to the TIMI score significantly improved risk stratification according to cfNRI and IDI. A BNP and the combination of the TIMI score with NGAL predicted the occurrence of the combined end point with an AUC of 80.6 or 82.2, respectively. NGAL alone is a simple tool to identify very high-risk patients. NGAL >110 pg/mL was associated with a 1-year mortality of 20%.

Conclusions

The measurement of NGAL together with the TIMI score results in a strong prognostic model for the 1-year mortality rate in patients with STEMI.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Strengths of this study include the evaluation of consecutive patients with STEMI treated by primary PCI; strictly given timepoints for evaluation of biomarkers in an acute phase of MI; comparison of a new biomarker (NGAL) with the 'gold standard' (BNP); and the addition of the evaluated biomarker to a validated clinical risk score (TIMI).

Limitations of this study are the monocentric character of the study and the evaluation of all-cause mortality rather than cardiovascular mortality.

Introduction

Acute heart failure (AHF),1 2 early development of left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction,3 LV remodelling,4 inflammatory responses during myocardial infarction (MI)5 6 or newly developed acute kidney injury (AKI)7 8 have been identified repeatedly to be independent and important factors influencing the long-term prognosis of patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Therefore, it can be assumed that a biomarker with a relationship with all of these pathways could be used to stratify patients with ACS. Such a biomarker could be neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL or lipocalin-2).

NGAL is a glycoprotein in complex with gelatinase stored in specific granules of mature neutrophils.9 NGAL is also produced by other cell types, including cardiomyocytes.10 NGAL is a component of the immune system. Secreted lipocalin-2 limits bacterial growth by binding bacterial siderophores, thereby preventing bacteria from retrieving iron from this source.11 Through direct binding with matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), NGAL inhibits its inactivation by tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) and leads to its enhanced proteolytic activity with prolonged effects on collagen degradation.12 MMP-9 activity appears to be important for LV remodelling after MI.13 The NGAL concentration in urine and serum represents a sensitive, specific and highly predictive early biomarker for AKI. Increased values of NGAL have been observed 2 h after cardiopulmonary bypass surgery.14 In patients with heart failure, in the early period after MI, NGAL levels are elevated in participants with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class-III heart failure compared with those with NYHA-I or NYHA-II heart failure, and elevated levels at baseline are associated with long-term adverse outcomes.10 An increased NGAL level has been demonstrated to be an independent predictor of mortality and cardiovascular disease in a community of older adults.15

On the basis of the relationship between NGAL and several negative prognostic issues in patients with ACS, we evaluated the benefits of measuring the NGAL level on hospital admission for prognostic stratification in addition to the clinical predictive scoring model TIMI. Also, we evaluated the benefit of measuring the NGAL level compared with B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) as one of the best studied biomarkers for risk stratification of patients with ACS.

Methods

Ethical approval of the study protocol

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before participation in the study. The study protocol complied with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Faculty Hospital Brno (Brno, Czech Republic).

Study population

Patients with acute ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) admitted to the Coronary Care Unit (CCU) of the Cardiology Department of University Hospital Brno were enrolled. The diagnosis of STEMI was based on symptoms consistent with MI in conjunction with appropriate changes on electrocardiography (ECG), that is, i.e., ST-segment elevation or new left bundle branch block. The patients were enrolled in the study immediately on admission according to the discretion of the attending physician. A marker of myocardial necrosis, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (hs-cTnI) was assessed exactly 24 h after the onset of chest pain. Exclusion criteria were: age >80 years; known or newly diagnosed malignancy; inflammatory disease or connective tissue disease; estimated life expectancy due to non-cardiovascular reasons <12 months; geographic factors (distance from the place of residence to the hospital of >100 km without the possibility of follow-up); and findings on coronary angiography of an absence of stenosis with reduction of the intraluminal diameter of coronary arteries >50%. Thirteen patients after cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation were not included in this analysis. Standard therapy (ie, ACE inhibitors (ACEIs), β-blockers, statins and dual antiplatelet therapy) was initiated as soon as possible. Patients were treated in accordance with current guidelines for the management of acute MI presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation.16 17 Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was undertaken mostly by radial access and, if needed, tromboaspiration was carried out.18 The diagnosis of AHF was assessed according to clinical signs on hospital admission and/or during hospitalisation (Killip class I–IV). Killip II was defined as pulmonary congestion with wet rales in the lower half of the lung fields or S3 gallop. Killip III (pulmonary oedema) was accompanied by severe respiratory distress, with crackles over the lungs and orthopnea with O2 saturation usually <90% before treatment. Killip IV (cardiogenic shock (CS)) was defined as evidence of tissue hypoperfusion induced by heart failure after correction of preload, mostly with systolic blood pressure (SBP) <90 mm Hg ongoing for ≥30 min.

Laboratory analyses

Samples of venous blood for NGAL and BNP analyses were drawn immediately on hospital admission before primary PCI. Samples were centrifuged within 10 min in a refrigerated centrifuge, and the plasma and serum were stored at –80°C. Standard biochemical and haematological blood tests were done immediately on hospital admission before primary PCI. Troponin I (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Illinois, USA) was analysed exactly 24 h after the onset of chest pain. BNP was analysed using the AxSYM BNP-Microparticle Enzyme Immunoassay (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, Illinois, USA). BNP on admission was available only for 431 patients. NGAL was analysed using NGAL Rapid Elisa kits (Bioporto Diagnostics, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Echocardiographic assessment

Echocardiography was carried out during the index admission (between the third and fifth day after MI onset). LV ejection fraction (LVEF) was estimated using the biplanar Simpson’s rule from apical two-chamber and four-chamber views. Echocardiography was assessed by one operator using the Vivid 7 system (GE Vingmed Ultrasound, Horten, Norway).

Follow-up

Patients were subsequently followed up at an outpatient clinic of the University Hospital Brno. Deaths, hospitalisations for AHF or MI, unplanned revascularisations (PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting) and strokes were recorded and evaluated. All surviving patients were followed up for at least 1 year; the median of follow-up was 2.7 years.

Statistical analyses

Standard descriptive statistics were applied in the analysis, that is, absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables, and median frequencies supplemented by 5th and 95th centiles for continuous variables. The statistical significance of differences among groups of patients was computed using the maximum likelihood χ2 test for categorical variables, and the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. Owing to the non-linearity of biomarkers, they were logarithmically transformed using the base logarithm of two.

The discriminative ability of the thrombolysis in MI (TIMI) score as well as levels of BNP and NGAL was evaluated by the c-statistic (identical to the area under the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve) with end points of 1-year all-cause mortality, hospitalisations for AHF, strokes, reinfarctions and unplanned revascularisations (PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting). The subgroup of patients with available BNP (431 patients) was comparable with the whole cohorts of patients, data not shown.

The ability of levels of BNP and NGAL to improve prediction of the TIMI score was evaluated. The biomarker was added to the TIMI score, and the area under the ROC curve was compared with TIMI alone. Biomarkers were used as continuous parameters in this model. Logistic regression was used to build the predictive model, which comprised the TIMI score and biomarkers. The addition of the predictive value of biomarkers to the score was assessed by category free net reclassification improvement (cfNRI) and the integrated discrimination index (IDI).

A multivariate model was performed to demonstrate NGAL and BNP as independent predictive factors of 1-year mortality. The multivariate model was built using logistic regression. Parameters included in the multivariate model were selected according to the statistical significance in univariate models. Two multivariate models were built, one without and one with BNP.

Results

Baseline characteristics

We evaluated 673 patients hospitalised due to confirmed STEMI. The baseline characteristics of the study population divided according to the tertiles of NGAL values are presented in table 1. The 1-year mortality was 6.4%. Patients with higher NGAL levels on hospital admission tended to be older; prior to admission, they were often treated with ACEI/ARBs and β blockers, they were more likely to have hypertension and AHF (Killip III and IV). Also, they had higher levels of creatinine and BNP and lower levels of haemoglobin on hospital admission.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics, therapy on hospital admission and laboratory description of patients according to the tertiles of NGAL values

| Tertiles of NGAL (pg/mL) |

p Value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤49.0 (N=226) |

49.1–89.0 (N=223) |

≥89.1 (N=224) |

||

| Age on admission | 61 (45; 79) | 61 (46; 78) | 64 (45; 77) | 0.017 |

| Sex (females) | 49 (21.6%) | 52 (23.3%) | 57 (25.4%) | 0.626 |

| Body mass index | 27.8 (22.6; 34.5) | 28.1 (22.7; 34.9) | 27.8 (22.3; 35.7) | 0.424 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 140 (95; 190) | 135 (100; 180) | 135 (90; 185) | 0.122 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 80 (56; 100) | 80 (60; 105) | 80 (58; 100) | 0.142 |

| Heart rate (/min) | 73 (51; 104) | 74 (53; 107) | 78 (49; 110) | 0.165 |

| TIMI score | 4 (2; 8) | 3 (1; 7) | 4 (1; 8) | 0.002 |

| AHF on admission | 51 (22.5%) | 43 (19.3%) | 62 (27.7%) | 0.106 |

| Killip II | 45 (19.8%) | 36 (16.1%) | 36 (16.1%) | 0.490 |

| Pulmonary oedema | 5 (2.2%) | 4 (1.8%) | 14 (6.3%) | 0.021 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 1 (0.4%) | 3 (1.3%) | 12 (5.4%) | 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 53 (23.3%) | 55 (24.7%) | 59 (26.3%) | 0.762 |

| Hypertension | 117 (51.5%) | 119 (53.4%) | 150 (67.0%) | 0.001 |

| Hyperlipoproteinaemia | 186 (81.9%) | 165 (74.0%) | 150 (67.0%) | 0.001 |

| History of MI | 17 (7.5%) | 22 (9.9%) | 29 (12.9%) | 0.156 |

| ACEI and/or ARBs | 63 (27.8%) | 75 (33.6%) | 103 (46.0%) | <0.001 |

| β blockers | 41 (18.1%) | 60 (26.9%) | 73 (32.6%) | 0.002 |

| LVEF (%) | 55 (35; 67) | 51 (34; 67) | 50 (28; 69) | 0.006 |

| Natrium (mmol/L) | 139 (132; 143) | 139 (134; 143) | 139 (133; 143) | 0.759 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.0 (3.2; 4.9) | 4.0 (3.2; 4.8) | 4.0 (3.2; 5.0) | 0.725 |

| Glycaemia (mmol/L) | 8.0 (5.7; 16.0) | 7.9 (5.4; 17.3) | 8.3 (5.4; 17.9) | 0.216 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 84 (58; 119) | 84 (59; 117) | 92 (63; 170) | <0.001 |

| Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.5 (3.5; 7.8) | 5.2 (3.5; 7.2) | 4.9 (3.1; 7.1) | <0.001 |

| Troponin I (pg/mL) | 44.4 (2.4; 164.9) | 54.1 (2.0; 150.6) | 53.3 (4.1; 227.9) | 0.549 |

| BNP (pg/mL)2 | 55 (15; 337) | 67 (15; 488) | 91 (23; 578) | <0.001 |

| NGAL (pg/mL) | 29.3 (17.9; 48.0) | 70.1 (52.9; 87.2) | 114.5 (91.8; 201.0) | <0.001 |

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 148 (125; 166) | 144 (118; 168) | 142 (115; 168) | 0.002 |

*Statistical significance of difference between groups of patients tested by the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous parameters and by ML χ2 for categorical parameters.

†BNP on admission is available only for 431 patients. Laboratory parameters were analysed on hospital admission. Only the level of troponin I was analysed 24 h after the onset of chest pain. Levels of cholesterol were analysed in fasting patients on the first morning of hospitalisation in patients who survived the first 24 h.

Bold typeface highlights statistically significant results.

AHF, acute heart failure; ACEI, ACE inhibitors; ARBs, antagonist for type 2 of receptor for angiotensin II; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; BP, blood pressure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

NGAL or BNP as independent predictive factors of 1-year mortality

Multivariable analyses were performed, and among important usual prognostic parameters (sex, age, SBP, AHF, diabetes mellitus, LVEF, body mass index, glycaemia, haemoglobin and creatinine), only NGAL (OR 1.939, 95% CI (1.313 to 2.863), p<0.001) and LVEF (OR 0.913, 95% CI (0.879 to 0.948), p<0.001) were identified as independent predictive factors of 1-year mortality. When BNP was also included in the model, only LVEF, body mass index and BNP were independent predictive factors (table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate models for prediction of 1-year mortality (with and without BNP)

| Model without BNP |

Model with BNP2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p Value* | OR | 95% CI | p Value* | |

| Sex (female) | 0.981 | 0.379 to 2.539 | 0.969 | 0.917 | 0.240 to 3.500 | 0.899 |

| Age | 1.033 | 0.986 to 1.082 | 0.167 | 1.016 | 0.947 to 1.089 | 0.667 |

| BMI | 1.023 | 0.936 to 1.119 | 0.613 | 1.131 | 1.006 to 1.272 | 0.039 |

| Systolic BP | 0.988 | 0.974 to 1.002 | 0.080 | 0.986 | 0.966 to 1.005 | 0.152 |

| AHF | 1.377 | 0.596 to 3.181 | 0.453 | 0.998 | 0.280 to 3.562 | 0.998 |

| DM | 2.695 | 1.049 to 6.925 | 0.039 | 2.310 | 0.609 to 8.768 | 0.219 |

| LVEF | 0.915 | 0.881 to 0.950 | <0.001 | 0.947 | 0.897 to 1.000 | 0.048 |

| Creatinine | 1.007 | 0.999 to 1.016 | 0.096 | 1.009 | 0.996 to 1.023 | 0.178 |

| Glycaemia | 0.999 | 0.908 to 1.100 | 0.987 | 1.033 | 0.902 to 1.184 | 0.636 |

| Haemoglobin | 0.988 | 0.964 to 1.013 | 0.361 | 0.986 | 0.948 to 1.026 | 0.489 |

| NGAL | 2.136 | 1.262 to 3.613 | 0.005 | 1.267 | 0.651 to 2.469 | 0.486 |

| BNP | – | – | – | 1.616 | 1.027 to 2.543 | 0.038 |

*Statistical significance.

†Model build only on 431 patients with BNP available on admission.

Bold typeface highlights statistically significant results.

AHF, acute heart failure; BMI, body mass index; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; BP, blood pressure; DM, diabetes mellitus; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; ML, maximum likelihood; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin.

Risk of death and hospitalisation due to AHF

According to calculated values of the ROC of the c-statistics, TIMI score, NGAL and BNP levels were able to detect patients on admission with risk of death or hospitalisation due to AHF during the first year. The best early predictor for risk of readmission due to AHF seems to be an elevated BNP value (AUC 87.0). There was no clinically significant relationship between the values of TIMI score, NGAL or BNP and the occurrence of stroke. We found only a weak relationship between increased levels of NGAL and BNP and the occurrence of unplanned revascularisation or reinfarction (AUC <70) (table 3). On the basis of these results, the combined end point of death and hospitalisation for heart failure was defined, which also considers the pathophysiological relationships with evaluated biomarkers.

Table 3.

Values of the c-statistics for the prediction of 1-year mortality, hospitalisations for acute heart failure, strokes, unplanned revascularizations (PCI or CABG) and infarctions according to TIMI score, NGAL and BNP on admission

| Death | Hospitalisation due to AHF | Stroke | Revascularization | Reinfarction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIMI score | 74.4 (66.8; 82.0)* | 72.8 (60.0; 85.6)* | 54.1 (35.5; 72.7) | 47.5 (41.6; 53.4) | 47.4 (41.3; 53.4) |

| NGAL (pg/mL) | 75.5 (67.3; 83.8)* | 72.1 (63.7; 80.5)* | 54.0 (44.5; 63.6) | 66.6 (61.6; 71.6)* | 67.2 (62.1; 72.4)* |

| BNP (pg/mL)† | 78.7 (68.7; 88.8)* | 87.0 (79.6; 94.3)* | 55.1 (36.7; 73.5) | 62.8 (53.8; 71.7)* | 67.4 (58.8; 76.1)* |

*Statistically significant AUC.

†BNP on admission is available only for 431 patients.

Bold typeface highlights statistically significant results.

AUC, area under the curve; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

According to c-statistics results, the optimal cut-off value for an increased risk of 1-year mortality was 150 pg/mL for the BNP level, and 84 pg/mL for the NGAL level on hospital admission (table 4). A combination of the clinical model TIMI score together with the NGAL level had the highest predictive value for prediction of the risk of death (AUC 83.6, sensitivity 83.7% and specificity 75.6%). The addition of BNP did not improve the model (table 4).

Table 4.

Values of the c-statistics for the prediction of 1-year mortality and occurrence of combined end point (death and/or hospitalisation for AHF) according to the TIMI score, NGAL and BNP on admission and their combination

| Marker | AUC (95% CI) | p Value* | Cut-off | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-year mortality | |||||

| TIMI score | 74.4 (66.8 to 82.0) | <0.001 | ≥5.5 | 58.1 | 78.3 |

| NGAL (pg/mL)† | 75.5 (67.3 to 83.8) | <0.001 | ≥84.0 | 79.1 | 65.5 |

| BNP (pg/mL)†‡ | 78.7 (68.7 to 88.8) | <0.001 | ≥150.2 | 72.7 | 78.5 |

| TIMI+NGAL‡ | 82.6 (75.7 to 89.5) | <0.001 | 79.1 | 78.8 | |

| TIMI+BNP†‡ | 79.7 (69.8 to 89.6) | <0.001 | 68.2 | 80.4 | |

| TIMI+NGAL+BNP†‡ | 80.9 (70.6 to 91.2) | <0.001 | 68.2 | 83.6 | |

| One-year occurrence of combined end point (death and/or hospitalisation for AHF) | |||||

| TIMI score | 74.1 (67.2 to 81.0) | <0.001 | ≥5.5 | 57.4 | 78.9 |

| NGAL (pg/mL)† | 74.2 (67.1 to 81.2) | <0.001 | ≥83.4 | 75.9 | 65.6 |

| BNP (pg/mL)†‡ | 80.6 (72.3 to 89.0) | <0.001 | ≥149.9 | 77.8 | 79.2 |

| TIMI+NGAL‡ | 82.0 (75.9 to 88.1) | <0.001 | 79.6 | 77.9 | |

| TIMI+BNP†‡ | 81.6 (73.3 to 89.8) | <0.001 | 74.1 | 79.2 | |

| TIMI+NGAL+BNP†‡ | 83.1 (74.5 to 91.6) | <0.001 | 74.1 | 84.4 | |

*Statistical significance of AUC.

†Parameters BNP and NGAL were logarithmically transformed with base 2 (log2(×)).

‡BNP on admission is available only for 431 patients.

Bold typeface highlights statistically significant results.

AUC, area under the curve; AHF, acute heart failure; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

Risk of combined end point

A BNP value of >150 pg/mL and the combination of the TIMI score with an NGAL level ≥83.4 pg/mL predicted the occurrence of the combined end point of death and/or hospitalisation for AHF with an AUC of 80.6 or 82.2, respectively. An addition of the TIMI score to the BNP did not improve the predictive value compared with BNP itself (table 3).

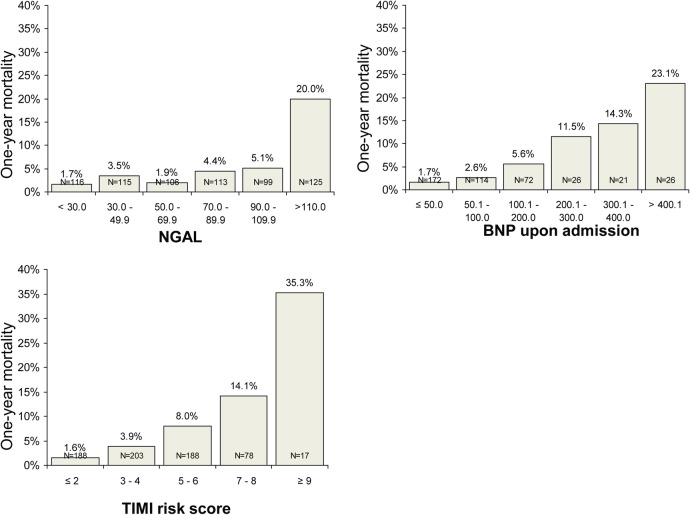

Reclassification analyses

The addition of the predictive value of NGAL, BNP and both biomarkers to the TIMI score was assessed by cfNRI and IDI. The estimated risk of mortality was calculated using the TIMI score for the study population. After using the new models, comprising either the TIMI score and BNP level, or the TIMI score and NGAL level, or the TIMI score and both BNP and NGAL levels, the predicted risk was recalculated. Further, cfNRI was used to evaluate if the addition of a biomarker (BNP, NGAL or both) led to a better reclassification of patients compared to the clinical model TIMI score. The inclusion of NGAL and BNP values led to significantly better categorisation of patients (80.6% and 55.7% of them were reclassified, respectively). The addition of both (NGAL and BNP) did not show better results. The integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) index for NGAL, BNP and both were 0.083, 0.038 and 0.060, respectively (all p<0.01) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Reclassification of 1-year mortality risk for death in patients with the addition of BNP, NGAL and BNP+NGAL to the TIMI score model. The addition of the predictive value of biomarkers to the TIMI score was assessed by cfNRI and the IDI. BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; cfNRI, category free net reclassification improvement; IDI, integrated discrimination index; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

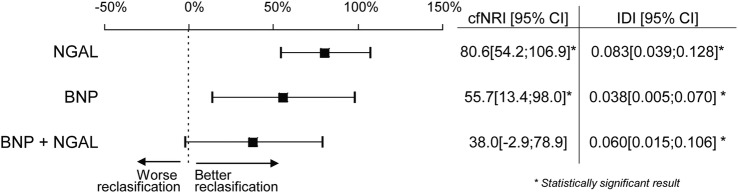

NGAL as a simple tool for risk stratification on admission

Figure 2 demonstrates NGAL as a simple tool for quick stratification of patients into three groups according to the risk of 1-year mortality: low-risk group with NGAL on admission <70 pg/mL (risk of death <3%, sensitivity 81.4%, specificity 52.14%, negative predictive value 97.6%; p<0.001), intermediate-risk group with NGAL 70–110 pg/mL (risk of death 3–5%) and high-risk group with NGAL ≥110 pg/mL (risk of death 20%, sensitivity 58.1%, specificity 84.2%).

Figure 2.

One-year mortality in groups of patients stratified according to the NGAL levels, BNP levels on admission and TIMI risk score. BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

Discussion

We evaluated the possibility of using the NGAL level for early risk stratification of patients with STEMI treated by primary PCI. The NGAL level was significantly higher in high-risk patients on hospital admission, as well as the values of BNP and the clinical model TIMI score. According to ROC analysis, NGAL, BNP and TIMI scores are useful for the early risk stratification of 1-year mortality and risk of readmission for AHF. Only weak or no association was detected between NGAL, BNP and TIMI scores and other evaluated cardiovascular end points (strokes, reinfarction and unplanned revascularisation).

In general, the prognostic value of biomarkers should be evaluated in addition to clinical scenarios. From this viewpoint, we have demonstrated that the NGAL and BNP levels bring a significant additive prognostic value to the TIMI score according to reclassification analyses. We used as a clinical model the TIMI score, although it was originally built for prediction of a 30-day mortality of patients with STEMI;1 later, it was validated and used for a 6-month and 1-year mortality.19–22

In a daily clinical practice, we need a simple tool to identify really high-risk patients requiring increased attention. A level of NGAL >110 pg/mL identifies very high-risk patients with a 1-year mortality of 20%.

Using multivariate analyses, we demonstrated that NGAL is truly an independent predictive factor of 1-year mortality. Although pathophysiological roles of both evaluated biomarkers, NGAL and BNP, seems to be complementary (the BNP level is affected primarily by congestion, increased myocardial stress and partly by ongoing ischemia,23 the NGAL level is related to possible future LV remodelling, renal injury within the cardiorenal syndrome, and inflammatory reactions) and evaluation of both markers simultaneously has no significance for a risk stratification in clinical practice.

Our results are consistent with a study that demonstrated in 584 patients with STEMI that an elevated value of NGAL above the 75th centile (170 pg/mL) is an independent prognostic factor of all-cause mortality and combined cardiovascular end point (cardiovascular mortality and hospital readmission due to recurrent MI or heart failure).24 In addition, we bring an evaluation of NGAL together with a validated clinical model and a comparison with BNP.

Study limitations

The present study had several limitations. First, it was at a single centre. Second, all-cause mortality but no cardiovascular mortality was evaluated. Third, more information would probably be obtained by the evaluation of NGAL in subsequent time points, Fourth, BNP was evaluated in only 431 patients, but baseline characteristics of this subgroup were comparable with the whole population.

Conclusion

An increased NGAL level assessed on hospital admission in patients with STEMI provides additional information to the established clinical model (TIMI score) for assessment of the risk of all-cause mortality at 1 year as well as the risk of all-cause mortality and readmission for AHF.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Ludmila Dostalova.

Contributors: KH, SL, PK, EG, MP, LK, JJ, MPG, JL, JG, PK, OT, MD, JS and JP contributed to the conception and design of the work; KH, SL, JJ and JP were involved in the analysis and interpretation of data; KH, SL, PK, EG, MP, LK, JJ, MPG, JL, JG, PK, OT, MD, JS and JP were involved in the drafting of the manuscript and its critical revision for important intellectual content, as well as the final approval of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Project of Conceptual Development of Research Organisation (Department of Health) 65 269 705, Grant MUNI/A/1544/2014 and by the European Regional Development Fund—Project FNUSA-ICRC (No.CZ.1.05/1.1.00/02.0123).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics Committee Universital Hospital Brno, Czech Republic.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi:10.5061/dryad.fp0k6.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Ludmila Dostalova

References

- 1.Morrow DA, Antman EM, Charlesworth A et al. TIMI risk score for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a convenient, bedside, clinical score for risk assessment at presentation: an intravenous nPA for treatment of infarcting myocardium early II trial substudy. Circulation 2000;102:2031–7. 10.1161/01.CIR.102.17.2031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morrow DA, Antman EM, Parsons L et al. Application of the TIMI risk score for ST-elevation MI in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 3. JAMA 2001;286:1356–9. 10.1001/jama.286.11.1356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halkin A, Singh M, Nikolsky E et al. Prediction of mortality after primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction: the CADILLAC risk score. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:1397–405. 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolognese L, Neskovic AN, Parodi G et al. Left ventricular remodeling after primary coronary angioplasty: patterns of left ventricular dilation and long-term prognostic implications. Circulation 2002;106:2351–7. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000036014.90197.FA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mueller C, Buettner HJ, Hodgson JM et al. Inflammation and long-term mortality after non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome treated with a very early invasive strategy in 1042 consecutive patients. Circulation 2002;105:1412–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scirica BM, Cannon CP, Sabatine MS et al. Concentrations of C-reactive protein and B-type natriuretic peptide 30 days after acute coronary syndromes independently predict hospitalization for heart failure and cardiovascular death. Clin Chem 2009;55:265–73. 10.1373/clinchem.2008.117192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox CS, Muntner P, Chen AY et al. Short-term outcomes of acute myocardial infarction in patients with acute kidney injury: a report from the national cardiovascular data registry. Circulation 2012;125:497–504. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.039909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parikh CR, Coca SG, Wang Y et al. Long-term prognosis of acute kidney injury after acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:987–95. 10.1001/archinte.168.9.987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kjeldsen L, Bainton DF, Sengeløv H et al. Identification of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as a novel matrix protein of specific granules in human neutrophils. Blood 1994;83:799–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yndestad A, Landrø L, Ueland T et al. Increased systemic and myocardial expression of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in clinical and experimental heart failure. Eur Heart J 2009;30:1229–36. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flo TH, Smith KD, Sato S et al. Lipocalin 2 mediates an innate immune response to bacterial infection by sequestrating iron. Nature 2004;432:917–21. 10.1038/nature03104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan L, Borregaard N, Kjeldsen L et al. The high molecular weight urinary matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity is a complex of gelatinase B/MMP-9 and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL). Modulation of MMP-9 activity by NGAL. J Biol Chem 2001;276:37258–65. 10.1074/jbc.M106089200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly D, Cockerill G, Ng LL et al. Plasma matrix metalloproteinase-9 and left ventricular remodelling after acute myocardial infarction in man: a prospective cohort study. Eur Heart J 2007;28:711–18. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mishra J, Dent C, Tarabishi R et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as a biomarker for acute renal injury after cardiac surgery. Lancet 2005;365:1231–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74811-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daniels LB, Barrett-Connor E, Clopton P et al. Plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin is independently associated with cardiovascular disease and mortality in community-dwelling older adults: the Rancho Bernardo Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:1101–9. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamm CW, Bassand JP, Agewall S et al. , ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: the Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2011;32:2999–3054. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steg PG, James SK, Atar D et al. , Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2569–619. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kala P, Miklik R. Pharmaco-mechanic antithrombotic strategies to reperfusion of the infarct-related artery in patients with ST-elevation acute myocardial infarctions. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 2013;6:378–87. 10.1007/s12265-013-9448-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aragam KG, Tamhane UU, Kline-Rogers E et al. Does simplicity compromise accuracy in ACS risk prediction? A retrospective analysis of the TIMI and GRACE risk scores. PLoS ONE 2009;4:e7947 10.1371/journal.pone.0007947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kozieradzka A, Kamiński K, Dobrzycki S et al. TIMI Risk Score accurately predicts risk of death in 30-day and one-year follow-up in STEMI patients treated with primary percutaneous coronary interventions. Kardiol Pol 2007;65:788–95; discussion 796–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lev EI, Kornowski R, Vaknin-Assa H et al. Comparison of the predictive value of four different risk scores for outcomes of patients with ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 2008;102:6–11. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.02.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brener SJ, Lincoff AM, Bates ER et al. The relationship between baseline risk and mortality in ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction treated with pharmacological reperfusion: insights from the Global Utilization of Strategies To open Occluded arteries (GUSTO) V trial. Am Heart J 2005;150:89–93. 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.01.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parenica J, Kala P, Jarkovsky J et al. Acute heart failure and early development of left ventricular dysfunction in patients with ST segment elevation acute myocardial infarction managed with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Vnitr Lek 2011;57:43–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindberg S, Pedersen SH, Mogelvang R et al. Prognostic utility of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in predicting mortality and cardiovascular events in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:339–45. 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]