Abstract

The majority of oral diseases present as growths and masses of varied cellular origin. Such masses may include simple hyperplasia, hamartoma, choristoma, teratoma, benign or malignant neoplasms. The distinguishing features of hamartomatous lesions are not certain, and often these non-neoplastic masses are indiscreetly denoted as neoplasms without weighing their pathology or biological behaviour. Essentially, understanding the dynamics of each of these disease processes forms an integral part of the appropriate treatment planning.

Keywords: Developmental disorders, hamartoma, oral cavity, syndrome, tumour

INTRODUCTION

The term hamartoma is derived from the Greek word “hamartia” referring to a defect or an error.[1] It was originally coined by Albrecht in 1904 to denote developmental tumour-like malformations.[2] It can be defined as a non-neoplastic, unifocal/multifocal, developmental malformation, comprising a mixture of cytologically normal mature cells and tissues which are indigenous to the anatomic location, showing disorganized architectural pattern with predominance of one of its components.[1,3,4,5] The occurrence of multiple hamartomas in the same patient is often referred as hamartomatosis or pleiotropic hamartoma.[3,6]

Hamartomas are commonly observed in lung, pancreas, spleen, liver and kidney. They are rare in the head and neck region.[3] Within the oral cavity, indigenous tissues that might result in hamartomatous growths include odontogenic and non-odontogenic epithelial derivatives, smooth and skeletal muscle, bone, vasculature, nerve and fat.[5] Few hallmarks of a hamartoma based on literature include:[3,5,7,8]

Developmental malformation may be present at birth, but manifests later

Self-limited growth, co-ordinated with that of the surrounding tissues

Can present as solitary or multiple masses

May regress spontaneously

Usually not encapsulated with ill-defined margins

Not a true neoplasm, but a true neoplasm may develop in a hamartoma

Microscopically, it consists of cytologically normal mature cells, native to the anatomic location

Association with chromosomal abnormalities and syndromes.

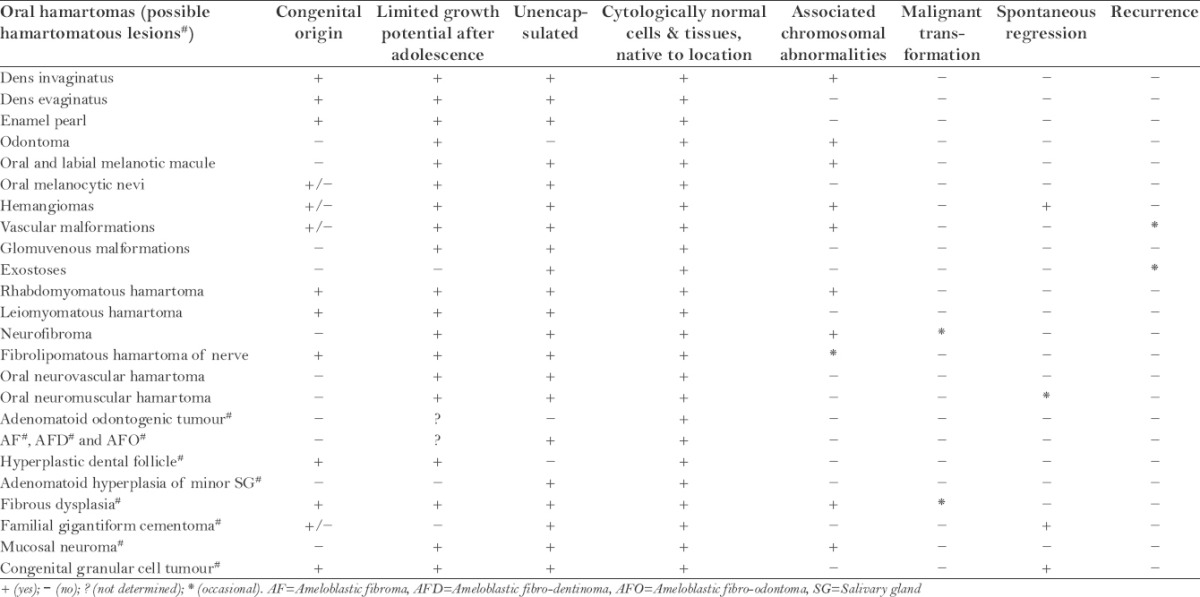

Nevertheless, not all the lesions stated as hamartomas in the literature justify completely the above features. According to the data tabulated in Table 1, the most important features perceived are its limited growth potential after adolescence, microscopic appearance of unencapsulated admixture of mature cells native to the anatomic location and association with chromosomal aberrations.

Table 1.

Summary of characteristic features of oral hamartomas

The pathogenesis of hamartomas still remains speculative.[1] They are derived from any one of the embryonic lineages, most commonly the mesoderm. This is almost never in the case of neoplasm, where the neoplastic cells are clonally derived.[9]

Clinically, majority are asymptomatic and rarely pose any complications except when situated at the base of tongue. Given the non-neoplastic nature of hamartomas, conservative surgical excision is the treatment of choice. The prognosis is excellent, with nil or minute chances of recurrence.[3]

HAMARTOMATOUS GROWTH OF ODONTOGENIC APPARATUS

Dens invaginatus

Dens invaginatus is a developmental anomaly resulting in invagination of the enamel organ into the dental papilla before the mineralization of the dental tissues begin. The prevalence is 0.3–10%. Associated syndromes include William's syndrome, Nance-Huran syndrome, cranial suture syndromes and Ekman-Westborg–Julin syndrome.[10,11]

Dens evaginatus

Dens evaginatus (DE) represents an accessory cusp and is predominantly seen in people of Asian descent with a varying incidence of 0.5–4.3%. Clinically, DE may cause malocclusion resulting in abnormal wear or fracture and is treated accordingly.[12]

Enamel pearl/Enameloma

They represent deposits of enamel located at the cemento-enamel junction or at the furcation area. Its prevalence varies between 1.1 and 9.7%. Rarely, it may be detected within the dentin, when it is known as internal enamel pearl. Clinical significance varies depending upon its topographic relation with the furcation area.[13,14]

Odontoma

According to Reichart and Philipsen and the World Health Organization (WHO) 2005, compound and complex odontomas are hamartomatous lesions.[15,16] They have a relative frequency of 4.2–73.8% and 5–30%, respectively.[15] Associated syndromes include Gardner's and Hermann's syndromes.[17]

HAMARTOMATOUS GROWTH OF EPITHELIAL DERIVATIVES

Oral and labial melanotic macule

They represent a well-circumscribed flat area of brown to black mucosal pigmentation. There is an increase in melanin production by normal mature melanocytes (without increase in their number).[18] It is associated with Peutz–Jeghers syndrome and Addison's disease.[19]

Oral melanocytic nevi

Nevi or mole represents collection of nevus cells which are derivatives of melanocytes or their precursor neural crest cells. Oral nevi are usually small and show regular symmetrical outline with no change in colour, shade or texture over time. Static nevi do not require excision and may be followed up.[19]

HAMARTOMATOUS GROWTH OF MESENCHYMAL DERIVATIVES

Congenital and infantile haemangioma

Congenital haemangioma (CH) and infantile haemangioma (IH) are present at birth or develop in the infancy period.[20,21] Majority of them involute spontaneously or gradually over the years. Microscopically, the proliferative phase of IH and CH comprises complex cellular mixtures, chiefly the endothelial cells.[20,22] Associated syndromes include PHACES and LUMBAR syndrome.[20]

Vascular malformations

Vascular malformation (VM) refers to congenital morphogenic anomalies of the various vessels.[20] Histologically, they comprise of normal vascular components.[20,22] VM may occur as primary or in association with regional or diffuse syndromes such as Sturge–Weber, Klippel–Trénaunay, proteus syndrome, Bannayan–Riley–Ruvalcaba syndrome, and Osler–Weber–Rendu, to mention a few.[20]

Glomuvenous malformations

Glomuvenous malformation (GVM) occurs more often in children.[23] Clinically, it appears as red-to-blue nodules or multifocal plaque-like lesions. Microscopically, GVM is composed of varying proportion of blood vessels and glomus cells. The familial cases have been linked to mutations in the glomulin gene located in chromosome 1p21-22.[22,24]

Exostoses

They are described as peripheral localized overgrowth of the bone. Based on the anatomic location in the jaws, they are termed as buccal bone exostoses, torus palatinus, and torus mandibularis.[25] Surgical intervention is required only in case of tissue trauma, periodontal or prosthodontic impediment.[26]

Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma

It is an exceptionally rare congenital lesion of the oral cavity. It chiefly comprises of striated muscle tissue.[27] It is associated with Delleman, amniotic band and Goldenhar syndromes.[28]

Leiomyomatous hamartoma

Leiomyomatous hamartoma is another rare entity which commonly involves the midline of palate and tongue. Microscopically, it consists of an unencapsulated mass of smooth muscle.[29,30]

Neurofibroma

As the name indicates, it is an admixture of perineural fibroblasts and Schwann cells. It is associated with von Recklinghausen's neurofibromatosis syndrome. Approximately 12% of cases are associated with the syndrome tend to develop malignancy.[6]

Fibrolipomatous hamartoma of nerve

Neural fibrolipoma or fibrolipomatous hamartoma of nerve (FLHN) is a tumour-like lipomatous process. FLHN was reported in the pharyngeal mucosa by Kumar et al.[31] Some lesions may represent carpal tunnel syndrome as a late complication.[23]

Oral neurovascular hamartoma

The hamartomatous nature of oral neurovascular hamartoma can be supported by the characteristics such as limited growth potential, ill-defined borders and histologically consisting of closely packed groups of well-formed nerve bundles and vessels.[5]

Oral neuromuscular hamartoma

Oral neuromuscular hamartomas or triton tumours are reported to occur in the trigeminal nerve and tongue. Histologically, they show presence of mature neural and striated muscle tissue.[32,33]

SYNDROMIC HAMARTOMAS

Tuberous sclerosis

Tuberous sclerosis (TS) is a rare syndrome characterized by the classic triad of seizures, mental deficiency and angiofibromas, affecting about 1 in 6000 people.[34] Oral hamartomas in TS were reported by Celenk et al. (2005) and Amin and O’Callaghan (2012).[34,35]

Cowden syndrome/multiple hamartoma syndrome

Cowden syndrome represents the principal PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) gene-related disorder which occurs in 1 in 200,000 people.[34] The oral manifestations include multiple papules involving the gingivae, buccal mucosa and dorsum of tongue.

Proteus syndrome

Proteus syndrome is a rare congenital hamartomatous condition with an incidence of less than 1 in a population of 1 million.[34] Reported associated oral hamartomas include exostoses of facial bones and lymphangiomas.[36]

Oral-facial-digital syndrome

Oral-facial-digital syndrome (OFDS) comprises a group of heterogeneous disorders with an incidence of 1 in 50,000–250,000 newborns.[34] The oral hamartomatous findings include lingual hamartomas (in 70% cases of OFDS I). Microscopically, they are composed of muscles, adipose tissues and salivary glands.[37]

CONTROVERSIAL ORAL HAMARTOMATOUS LESIONS

Adenomatoid odontogenic tumour

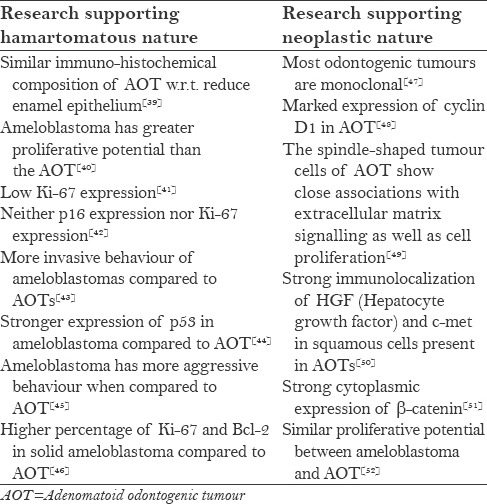

The hamartomatous nature of adenomatoid odontogenic tumour is supported by its limited growth potential and lack of recurrence.[38] Nevertheless, its biological behaviour has been a topic of long debate and the related research is depicted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Literature relevant to the biological behaviour of AOT

Ameloblastic fibroma, ameloblastic fibro-dentinoma and fibro-odontoma

Reichart and Philipsen proposed a neoplastic and hamartomatous line of development for the mixed odontogenic tumours. But currently, there is no substantial evidence to prove either of the above hypothesis.[15]

Hyperplastic dental follicle

It has been referred as an odontogenic hamartomatous lesion associated with single/multiple unerupted teeth. It commonly involves permanent first and second molars. Microscopically, it comprises of odontogenic epithelium and calcifications.[53,54]

Adenomatoid hyperplasia of minor salivary gland

It is a rare lesion of the minor salivary glands. Clinically it presents as a solitary, painless mass or nodule.[6] Microscopically, it comprises of lobular aggregates of normal mucus acini.[6,25] Recurrence and malignancy are not reported.[6]

Fibrous dysplasia

Fibrous dysplasia is a developmental tumour-like condition that becomes relatively static after skeletal maturation.[6,25] It is associated with Jaffe–Lichtenstein syndrome, McCune Albright syndrome, and Mazabraud's syndrome.[25] Malignant transformation is reported in 0.5% (1 in 200) of cases.[6]

Familial gigantiform cementoma

It is an extremely rare cemento-osseous disease restricted to the jaws.[55,56] Its growing potential can be correlated with skeletal growth and maturation.[55] If left untreated, the enlargement eventually ceases during the fifth decade.[25]

Mucosal neuroma

It is commonly associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) IIB syndrome. Clinically, it occurs in multiple small masses. Microscopically, it is partially encapsulated and contains aggregation or proliferation of histologically normal nerves.[6]

Congenital granular cell tumour

Congenital granular cell tumour is thought to be a variant of granular cell tumour, but the exact nature of the lesion is unclear. It exclusively occurs in infants or immediately after birth. Most of the lesions cease to grow or regress spontaneously without intervention.[19,23]

CONCLUSION

Oral hamartomas are unique presentations of the head and neck region. Nevertheless, the criteria to delineate hamartomas from other similar masses are ambiguous. To conclude, hamartomas should promptly be included in the differential diagnosis of the tumours of oral cavity, essentially the paediatric tumours, to avoid aggressive treatment and morbidity.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pilch BZ. Larynx and hypopharynx. In: Pilch BZ, editor. Head and Neck Surgical Pathology. Philadelphia, USA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001. pp. 230–83. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Craig O. Hamartoma. Postgrad Med J. 1965;41:636–8. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.41.480.636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes L. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. New York, USA: Marcel Dekker; 2001. Surgical Pathology of the Head and Neck; pp. 1649–72. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC, editors. 9th ed. Philadelphia, USA: Saunders, Elsevier; 2013. Robbins Basic Pathology; p. 257. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allon I, Allon DM, Hirshberg A, Shlomi B, Lifschitz-Mercer B, Kaplan I. Oral neurovascular hamartoma: A lesion searching for a name. J Oral Pathol Med. 2012;41:348–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2011.01101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gnepp DR. Intraosseous mucoepidermoid carcinoma. In: Gnepp DR, editor. Diagnostic Surgical Pathology of the Head and Neck. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, USA: Saunders, Elsevier; 2009. pp. 816–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Das S. A Concise Textbook of Surgery. 3rd ed. Calcutta, India: Dr. S. Das; 2001. p. 457. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walter JB, Israel MS. In: General Pathology. 6th ed. Walter JB, Israel MS, editors. USA: Churchill Livingstone; 1987. pp. 117–2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berman JJ. USA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2009. Neoplasms: Principles of Development and Diversity; p. 429. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alani A, Bishop K. Dens invaginatus. Part 1: Classification, prevalence and aetiology. Int Endod J. 2008;41:1123–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bishop K, Alani A. Dens invaginatus. Part 2: Clinical, radiographic features and management options. Int Endod J. 2008;41:1137–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levitan ME, Himel VT. Dens Evaginatus: Literature review, pathophysiology and comprehensive treatment regimen. J Endod. 2006;32:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chrcanovic BR, Abreu MH, Custódio AL. Prevalence of enamel pearls in teeth from a human teeth bank. J Oral Sci. 2010;52:257–60. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.52.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akgül N, Caglayan F, Durna N, Sümbüllü MA, Akgül HM, Durna D. Evaluation of enamel pearls by cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012;17:e218–22. doi: 10.4317/medoral.17475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reichart PA, Philipsen HP. London, UK: Quintessence Publishing Co. Ltd; 2004. Odontogenic Tumors and Allied Lesions; pp. 41–115. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. USA: WHO Publications Center; 2005. [Last accessed on 2015 Feb 28]. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: Pathology and Genetics Head and Neck Tumours. Available from: www.iarc.fr/IARCPress/pdfs/index1.php . [Google Scholar]

- 17.Satish V, Prabhadevi MC, Sharma R. Odontome: A brief review. Intl J Clinical Ped Dentistry. 2011;4:177–85. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenberg MS, Glick M, Ship JA. 11th ed. Ontario: BC Decker Inc; 2008. Burket's Oral Medicine; pp. 131–2. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marx RE, Stern D. 1st ed. Illinois, USA: Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc; 2003. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology: A Rationale for Diagnosis and Treatment; pp. 707–36. (427-28). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lowe LH, Marchant TC, Rivard DC, Scherbel AJ. Vascular malformations: Classification and terminology the radiologist needs to know. Semin Roentgenol. 2012;47:106–17. doi: 10.1053/j.ro.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ethunandan M, Mellor TK. Haemangiomas and vascular malformations of the maxillofacial region: A review. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;44:263–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2005.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.North PE. Pediatric vascular tumors and malformations. Surg Pathol. 2010;3:455–94. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, Folpe AL. 4th ed. Philadelphia, USA: Mosby, Elsevier; 2008. Enzinger and Weiss's Soft Tissue Tumors; pp. 617–18. (1187-88). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marler JJ, Mulliken JB. Current management of hemangiomas and vascular malformations. Clin Plast Surg. 2005;32:99–116. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2004.10.001. ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. 3rd ed. India: Saunders, Elsevier; 2009. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology; pp. 163–6. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smitha K, Smitha GP. Alveolar exostosis revisited: A narrative review of the literature. Saudi J Dent Res. 2015;6:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dal Vechio A, Nakajima E, Pinto D, Jr, Azevedo LH, Migliari DA. Rhabdomyomatous (mesenchymal) hamartoma presenting as haemangioma on the upper lip: A case report with immunohistochemical analysis and treatment with high-power lasers. Case Rep Dent 2013. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/943953. 943953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodrigues FA, Cysneiros MA, Rodrigues Jr R, Sugita DM. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma: A case report. J Bras Patol Med Lab. 2014;50:165–8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nava-Villalba M, Ocampo-Acosta F, Seamanduras-Pacheco A, Aldape-Barrios BC. Leiomyomatous hamartoma: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105:e39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iida S, Kishino M, Senoo H, Okura M, Morisaki I, Kogo M. Multiple leiomyomatous hamartoma in the oral cavity. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:241–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar N, Mittal M, Sinha M, Thukral B. Neural fibrolipoma in pharyngeal mucosal space: A rare occurrence. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2012;22:358–60. doi: 10.4103/0971-3026.111491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castro DE, Raghuram K, Phillips CD. Benign triton tumor of the trigeminal nerve. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:967–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daley TD, Darling MR, Wehrli B. Benign Triton tumor of the tongue. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105:763–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Genetic Home Reference. [Last accessed on 2015 Feb 27]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim .

- 35.Celenk P, Alkan A, Canger EM, Günhan O. Fibrolipomatous hamartoma in a patient with tuberous sclerosis: Report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;99:202–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Becktor KB, Becktor JP, Karnes PS, Keller EE. Craniofacial and dental manifestations of proteus syndrome: A case report. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2002;39:233–45. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_2002_039_0233_cadmop_2.0.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mihci E, Tacoy S, Ozbilim G, Franco B. Oral-facial-digital syndrome type 1. Indian Pediatr. 2007;44:854–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tegginamani A, Kudva S, Shruthi D K, Karthik B, Hargavannar VC. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor-hamartoma/cyst or true neoplasm; a Bcl-2 immunohistochemical analysis. Indian J Dent Adv. 2012;4:730–5. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crivelini MM, Soubhia AMP, Felipini RC. Study on the origin and nature of the adenomatoid odontogenic tumor by immunohistochemistry. J Appl Oral Sci. 2005;13:406–12. doi: 10.1590/s1678-77572005000400017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barboza CA, Pereira Pinto L, Freitas Rde A, Costa Ade L, Souza LB. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and p53 protein expression in ameloblastoma and adenomatoid adontogenic tumor. Braz Dent J. 2005;16:56–61. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402005000100010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leon JE, Mata GM, Fregnani ER, Carlos-Bregni R, de Almeida OP, Mosqueda-Taylor A, et al. Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 39 cases of adenomatoid odontogenic tumour: A multicentric study. Oral Oncol. 2005;41:835–42. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suzuki H, Hashimoto K. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumour of the maxilla: Immunohistochemical study. Asian J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;17:267–72. [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Medeiros AM, Nonaka CF, Galvão HC, de Souza LB, Freitas Rde A. Expression of extracellular matrix proteins in ameloblastoma and adenomatoid odontogenic tumors. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;267:303–10. doi: 10.1007/s00405-009-0996-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salehinejad J, Zare-Mahmoodabadi R, Saghafi S, Jafarian AH, Ghazi N, Rajaei AR, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of p53 and PCNA in ameloblastoma and adenomatoid odontogenic tumor. J Oral Sci. 2011;53:213–7. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.53.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krishna A, Kaveri H, Naveen RKumar K, Kumaraswamy KL, Shylaja S, Murthy S. Overexpression of MDM2 protein in ameloblastomas as compared to adenomatoid odontogenic tumor. J Cancer Res Ther. 2012;8:232–7. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.98976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Razavi SM, Tabatabaie SH, Hoseini AT, Hoseini ET, Khabazian A. A comparative immunohistochemical study of Ki-67 and Bcl-2 expression in solid ameloblastoma and adenomatoid odontogenic tumor. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2012;9:192–7. doi: 10.4103/1735-3327.95235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gomes CC, Oliveira Cda S, Castro WH, de Lacerda JC, Gomez RS. Clonal nature of odontogenic tumor. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009;38:397–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kumar H, Vandana R, Kumar G. Immunohistochemical expression of cyclin D1 in ameloblastomas and adenomatoid odontogenic tumors. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2011;15:283–7. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.86685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsuneki M, Maruyama S, Yamazaki M, Cheng J, Saku T. Podoplanin expression profiles characteristic of odontogenic tumor-specific tissue architectures. Pathol Res Pract. 2012;208:140–6. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2011.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poomsawat S, Punyasingh J, Vejchapipat P, Larbcharoensub N. Co-expression of hepatocyte growth factor and c-met in epithelial odontogenic tumors. Acta Histochem. 2012;114:400–5. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harnet JC, Pedeutour F, Raybaud H, Ambrosetti D, Fabas T, Lombardi T. Immunohistological features in adenomatoid odontogenic tumor: Review of the literature and first expression and mutational analysis of β-catenin in this unusual lesion of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71:706–13. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moosvi Z, Rekha K. c-Myc oncogene expression in selected odontogenic cysts and tumors: An immunohistochemical study. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2013;17:51–6. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.110725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cho YA, Yoon HJ, Hong SP, Lee JI, Hong SD. Multiple calcifying hyperplastic dental follicles: Comparison with hyperplastic dental follicles. J Oral Pathol Med. 2011;40:243–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2010.00968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmitd LB, Bravo-Calderón DM, Soares CT, Oliveira DT. Hyperplastic dental follicle: A case report and literature review. Case Rep Dent 2014. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/251892. 251892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abdelsayed RA, Eversole LR, Singh BS, Scarbrough FE. Gigantiform cementoma: Clinicopathologic presentation of 3 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;91:438–44. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.113108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eversole R, Su L, ElMofty S. Benign fibro-osseous lesions of the craniofacial complex. A review. Head Neck Pathol. 2008;2:177–202. doi: 10.1007/s12105-008-0057-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]