Abstract

Pigmentations are commonly found in the mouth. They represent in various clinical patterns that can range from just physiologic changes to oral manifestations of systemic diseases and malignancies. Color changes in the oral mucosa can be attributed to the deposition of either endogenous or exogenous pigments as a result of various mucosal diseases. The various pigmentations can be in the form of blue/purple vascular lesions, brown melanotic lesions, brown heme-associated lesions, gray/black pigmentations.

KEY WORDS: Endogenous, exogenous, oral mucosa, pigmentation

Pigmentation is defined as the process of deposition of pigments in tissues. Various diseases can lead to varied colorations in the mucosa. Pigmented lesions of oral cavity are due to:

Augmentation of melanin production

Increased number of melanocytes (melanocytosis)

Deposition of accidentally introduced exogenous materials.[1,2,3,4]

Oral pigmentation may be physiologic or pathologic. Pathologic pigmentation can be classified into exogenous and endogenous based upon the cause [Tables 1 and 2].[2] Exogenous pigmentation could be induced by drugs, tobacco/smoking, amalgam tattoo or heavy metals induced. And endogenous pigmentation can be associated with endocrine disorders, syndromes, infections, chronic irritation, reactive or neoplastic [Table 3].

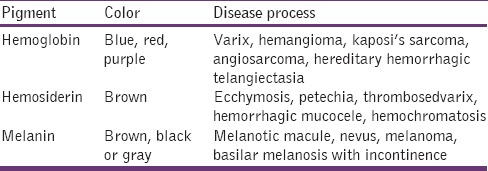

Table 1.

Endogenous pigmentation in oral mucosal disease

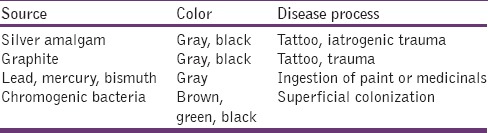

Table 2.

Exogenous pigmentation of oral mucosa

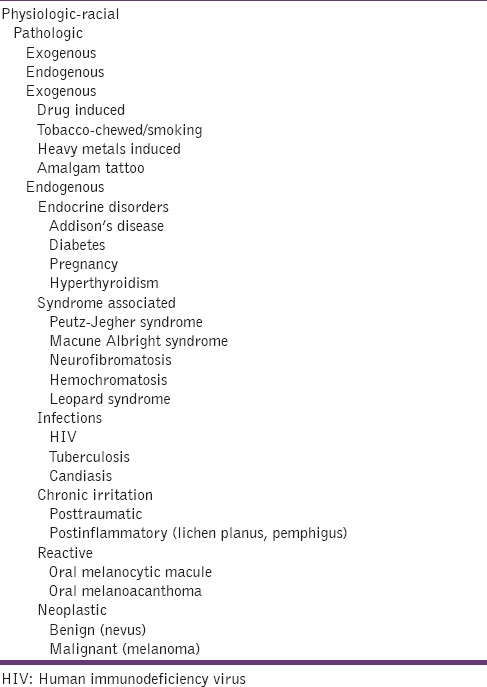

Table 3.

Classification of oral pigmentation

Melanin

There are four pigments which contribute to the normal color of the skin and mucosa.

Melanin

Carotenoids

Reduced HB

Oxygenated HB.

Of these four pigments, melanin is the most important. Melanin is an endogenous nonhematogenous pigment. It is produced by melanocytes in the basal layer of the epithelium and is transferred to adjacent keratinocytes via membrane-bound organelles called melanosomes. It is also synthesized by nevus cells, which are neural crest derivatives and are found in the oral mucosa and skin. Depending on the location and amount of melanin in the tissues, melanin induced pigmentation can be either black, gray, blue or brown in color.[5,6] Oral melanin pigmentation has been reported even among healthy individuals of the dark skinned African population to the prevalence of 100% and in Asians between 30% and 98%.[7] The different types of melanin are

Eumelanin

Pheomelanin

Mixed type melanin

Neuromelanin

Oxymelanin.

Drugs

Pigmentation can be produced by various drugs like, hormones, oral contraceptives, chemotherapeutic agents like cyclophosphamide, busulfan, bleomycin and fluorouracil, transquilizers, antimalarials like clofazamine, chloroquine, amodiaquine, anti-microbial agents like minocycline, anti-retroviral agents like zidovudine and antifungals like ketaconazole.

Palate and gingiva are most common sites affected. In addition to mucosal changes, teeth in adults and children may be bluish gray owing to minocycline/tetracycline use. The pathogenesis underlying drug-related pigmentation can be categorized as that occurs because of drug or drug metabolite deposition in dermis and epidermis, enhanced melanin deposition with or without increase in melanocytes, drug-induced post-inflammatory changes to the mucosa especially if the drugs induce an oral lichenoid reaction and bacterial metabolism, alone or in combination, may result in oral pigmentations.[7]

Tobacco

Tobacco habits are practiced in different forms, and many of these habits are specific to certain areas of India. This habit may broadly be classified as smoked tobacco and smokeless tobacco. May occur in up to one of five smokers, especially females taking birth control pills or hormone replacement than in men. Gingival pigmentation in children has been linked to passive smoking from parents and other adults who smoke.[8] Saraswathi et al. in their clinic pathological study reported that the intensity of the pigmentation was more in the labial mucosa than in the buccalmocosa. Also, they mentioned that the pigmentation was absent in smokeless tobacco users but mild pigmentation was observed away from the site of quid placement with the concurrent increase in number of melanocytes and melanocytic activity.[4,8]

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

In human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) the immune system is dysregulated, which leads to increase in inflammatory mediators like interleukin (IL)-1, (IL)-6, tumor necrotic factor (TNF) α which in turn cause a febrile response, as a result of which α melanocytes stimulating hormone (MSH) is released from the anterior pituitary. This opposes the fever induced by IL-1, 6, TNF, α. The αMSH is a potent stimulator of melanocyte, and IL-1 upregulates MSH receptor expression by melanocytes. Therefore, the body's natural mechanism for controlling fever and inflammation lead to the release of αMSH, which contributes to pigmented lesions in HIV patients.[9]

In HIV, the patient is infected by mycobacterium avium, which in turn involves the adrenal cortex and cause its destruction. The adrenal hypofunction causes increase in level of adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH) and MSH as a negative feedback, which causes hyperpigmentation in these patients. Also drugs like ketaconazole, zidovudine given to treat these patients cause oral pigmentation.[9,10]

Tuberculosis

Tuberculous infection can destroy the adrenal gland, and it accounts for <20% of cases of Addison's disease in the developed countries. In 1849, adrenal insufficiency was identified first by Dr. Thomas Addison Tuberculosis (TB) was the most common cause of Addison's disease during those times. As, treatment of TB improved, the incidence of adrenal insufficiency due to TB of adrenal glands also showed a great reduction. Here too the pigmentation can be due to the Addisonian effect.[11]

Candidasis

The first description of the association between hypoparathyroidism and candidiasis was published in 1929, and the association of these two diseases with idiopathic adrenal insufficiency was reported in 1946. Autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy is a rare, hereditary disease with the classic triad of mucocutaneous candidiasis, adrenocortical failure, and hypoparathyroidism. Any two of these triad is required for the diagnosis. The first clinical manifestation to appear is candidasis in majority of cases, usually before the age of 5 years, followed by hypoparathyroidism (usually before the age of 10 years), and later by Addison's disease (usually before 15 years of age).[12] Therefore here too the pigmentation probably should be because of Addissonian effect. Furthermore antifungal like ketoconazole also cause oral pigmentation possibly by ACTH pathway.

Heavy Metals

Increased levels of heavy metals (e. g., lead, bismuth, mercury, silver, arsenic and gold) in the blood are commonly known to cause oral mucosal discoloration. Various metals cause various types of pigmentation. For example, pigmentation due to lead poisoning also called as plumbism appears as a blue-black line along the marginal gingiva known as Burtonian line. Occupational exposure to heavy metal vapors is the common cause of pigmentation in adults. The most common cause in the past was, treatment of syphilis with drugs containing heavy metals, such as arsenicals for syphilis.[13,9]

Amalgam Tattoo

Amalgam tattoo is one of the most common causes of intraoral pigmentation. Amalgam tattoos are twice as common as melanotic macules and 10 times as common as oral nevi.[9] The gingiva and alveolar mucosa are most commonly involved. It presents clinically as a localized, blue-gray lesion. Biopsy should be performed to demonstrate the presence of amalgam particles in the connective tissue, in cases of doubt. Reasons for amalgam tattoo are:

(1) Previous areas of mucosal abrasion can be contaminated by amalgam dust within the oral fluids (2) broken amalgam pieces can fall into extraction sites (3) if dental floss becomes contaminated with amalgam particles of a recently placed restoration, linear areas of pigmentation can be created in the gingival tissue as a result of hygiene procedures (4) amalgam from the endodontic retrofill procedures can be left within the soft tissue at the surgical site (5) fine metal particles can be driven through the oral mucosa from the pressure of high-speed air turbine drills.[13,14]

Graphite

Sometimes, graphite may be incorporated into the oral mucosa through accidental injury with a graphite pencil which in turn cause pigmentation. This kind of lesion commonly occurs in children. Clinically, it appears as an irregular gray to black macule in the anterior palate region. Malignant lesions like melanoma should be differentiated from these lesions as melanoma too commonly occurs on the palate.[9]

Addisons Disease

Autoimmune destruction of the adrenal glands, also known as autoimmune adrenalitis, is now the most common cause of Addison disease in both children and adults.

Hyperpigmentation of the skin and mucosal surfaces, the most specific sign of Addison disease, occurs in up to 92% of patients. This dyspigmentation may precede other manifestations by up to 10 years.

Pigmentation of the oral mucosa is considered pathognomonic for Addison disease. The oral hyperpigmented macules of Addison disease can be found diffusely on the tongue, gingiva, buccal mucosa, and hard palate. The macules tend to be blue-black or brown and can be spotty or streaked in the configuration. Hyperpigmentation associated with Addison disease presumably occurs secondary to overproduction of the pro-opiomelanocortin byproduct-lipotropin, which is secreted in excess amounts concomitantly with corticotrophin from the pituitary gland because of the lack of feedback inhibition seen in adrenal insufficiency states. Cushing's syndrome, acromegaly and hyperthyroidism also show pigmentation similar to Addison's disease.[9,13]

Pregnancy

Pregnancy and aging can alter the body and in some cases lead to xazskin dysfunction. Skin becomes more sensitive to MSH and tyrosinase and can develop hyperpigmentation. After pregnancy, melasma - the mask of pregnancy is commonly seen in women. Pigmentation is seen on the face, usually on the upper lip, cheeks, and forehead. It is because the release of a hormone in pregnancy has signaled these distinct areas of the face.

Thyrotoxicosis

Thyroid hormone affects the normal pigmentation of the skin. Both vitiligo and hyperpigmentation have been associated with thyrotoxicosis. Depigmentation that resembles vitiligo seen in thyrotoxicosis may precede thyroid symptoms by many years. Hyperpigmentation may occur in about 7% of cases. It may be a brown diffuse pigmentation or may be localized to the face, neck and palmar creases. There is no mucosal or genital hyperpigmentation in contrast to Addison's disease. The exact mechanism of hyper and hypopigmentation in thyroid disease is not known. Both autoimmune and thyroid hormone effects are probably responsible. Another theory of explaining these hyperpigmentation could be due to hyperactivity of the sympathetic nervous system.[15,16]

Polyostotic Fibrous Dysplasia

Fibrous dysplasia is a developmental tumor-like lesion in which the bone is replaced by dysplastic fibrous tissue intermixed with irregular bony trabaculae. It occurs because of GNAS 1 mutation. The undifferentiated stem cells during the early embryonic life, the osteoblasts, melanocytes and endocrine cells that represent the progeny of that mutated cell all will carry that mutation and express the mutated gene. It is classified as monostotic (single bone) and polyostotic (multiple bones).

The polyostotic form can be of Jaffe-Lichtenstein or McCune Albright type. Café au lait pigmentation is the common feature in both the for the borders are irregular and called as the coastline of maine. In McCune Albright, additional endocrinopathies are present like sexual precocity, pituitary adenomas or hyperthyroidisim.[13]

Neurofibromatosis

Neurofibromatosis is an autosomal dominant disorder with a high degree of penetrance and variable expressivity. They are classified as neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) and NF2. Café au lait pigmentation of the skin is commonly seen in NF1. They appear as light brown, oval patches of size more than 5 cm in diameter, the borders of which are smooth, which are compared to the coast of California. It is also known as von Recklinghausen's disease of the skin.[13]

Hemochromatosis

It was first described by von Recklinghausen in 1889. It is characterized by excessive accumulation of body iron most of which is deposited in parenchymal organs like liver and pancreas and also deposited in other organs. It is a homozygous-recessive inherited disorder that is caused by excessive iron absorption.

Secondary hemochromatosis or acquired hemochromatosis or hemosiderosis occurs as a consequence of parenteral administration of iron, which results in accumulation of iron in tissues. The total body iron pool ranges from 2 g to 6 g in normal adults out of which about 0.5 g is stored in the liver, 98% of which is in hepatocytes. In hemochromatosis, the total iron accumulation may exceed 50 g, over one-third of which accumulates in the liver. Skin pigmentations occur in 75–80% of patients.[15]

Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder. It is associated with germline mutations in the LKB1/STK11 gene, located on the short arm of the chromosome. The syndrome consisted of mucocutaneous macules, intestinal polyposis and increased the risk of carcinomas of the pancreas, gastro-intestinal tract, thyroid, and breast. The macular melanin deposits often involve the lips, buccal mucosa, and fingers. Lesions may also develop on the gingiva, palate, and tongue. Histologically, the oral lesions show an increase in melanin in the basal layer, without an obviously increased melanocyte count. The spots are usually found to fade or disappear in older age 70.[16,17]

Laugier-Hunziker Syndrome

Laugier-Hunziker syndrome is a rare acquired macular hyperpigmentation of oral mucosa and lips frequently associated with longitudinal pigmentation of the nails of unknown cause. Ultrastructural studies have revealed an increase in the number and size of mature melanosomes located in the cytoplasm of basal keratinocytes and dermal melanophages.[8] Few studies have suggested that functional alteration of the melanocytes in the form of an increased production of melanosomes and its subsequent transport to the basal layer cells may give rise to hyperpigmented lesions.[18]

LAMB and LEOPARD Syndrome

LAMB syndrome is characterized by lentigines of the skin and mucosa (lentigines are small, pigmented flat or slightly raised spot with a clearly defined edges that is surrounded by normal-appearing skin or mucosa), atrial and mucocutaneousmyxomas, and multiple blue nevi, while LEOPARD syndrome is characterized by lentigines, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonic stenosis, electrocardiographic abnormalities, abnormalities of genitalia, deafness and retardation of growth.[19]

Posttraumatic Pigmentation

Discoloration that occurs due to hematoma secondary to trauma that leads to hemosiderin deposition, which gives a bluish black discoloration. The color varies from red to blue to purple depending on the age of the lesion and the degree of degradation of the extravasated blood. The clinical feature of these lesions occasionally may be confused with pigment deposition of hematogenous origin. Soft tissue hemorrhagic lesions usually appear in areas accessible to trauma such as the buccal mucosa, lateral tongue surface, lips and junctional of the hard and soft palate.[20]

Postinflammatory Pigmentation

Mucosal diseases in particular lichen planus can cause mucosal pigmentation. These pigmented areas clinically present as multiple brown-black pigmented areas adjacent to reticular or erosive lesions of lichen plants. These areas microscopically show increased production of melanin by the melanocytes and accumulation of melanin-laden macrophages in the superficial connective tissue.[17]

Pigmented Cellular Nevus

Nevis is also called birthmarks. Pigmented cellular nevus is a benign hamartomatous proliferation of the nevus cell either in the epithelium or in the connective tissue. They are basically classified as congenital or acquired. Based on their size the congenital melanocytic nevi are further classified as giant melanocytic congenital nevi (>20 cm) and small melanocytic congenital nevi (<1.5 in diameter). The giant melanocytic congenital nevi are also called as garment nevus, bathing trunk nevus or giant hairy nevus. The acquired melanocytic nevus frequently occurs on the skin and is commonly called as a mole. The hard palate is the common intraoral site. Microscopically based on the location of the nexus cells, they are classified as junctional, intradermal or intramucosal and compound nevi. The color also varies based on the location of nevus cells. Superficial nevi like junctional nevi are darker brown when compared to deeper intramucosal and compound nevi, which are lighter brown. In blue nevi, the blue color of the lesion can be accounted to the fact that the dermal melanocytes proliferate within the deeper part of the connective tissue, far from the surface epithelium (Tyndal effect).[9,13]

Labial Melanotic Macule (Labial Lentigo)

Labial melanotic macule is flat, oval, well defined, solitary brownish black patch which ranges from 1 mm to 8 mm in diameter. These lesions commonly occur on the lower lip with predilection for women.[6] Ultraviolet radiation exposure is thought to be the important etiology this lesion.

Oral Melanotic Macule

Oral melanotic macule is a flat, brown, solitary or multiple mucosal discoloration of oral mucosa, which is produced by a focal increase in melanin deposition along with an increase in melanocyte count. The most commonly involved sites are lip, buccal mucosa, gingiva and palate. Melanin deposition, mainly around the basal layers can be observed on microscopical examination of the lesion.

Oral Melanoacanthoma

Oral melano acanthoma was reported in 1978. It is a rare, reactive, benign lesion of the oral mucosa. It occurs frequently in younger age group with female predilection with buccal mucosa being the most common site. Clinically they appear ad dark brown to black hyperpigmented slightly raised lesion. Microscopically the lesion is characterized by melanocyte proliferation along the acanthotic, hyperkeratotic epithelium.[21]

Pigmented Malignant Lesion

Malignant melanoma

Melanoma is a malignant neoplasm of the epidermal melanocytes. Benign lesions like common acquired nevus, congenital nevus, dysplastic nevus and cellular blue nevus are said to undergo a malignant transformation to melanoma.

Criteria for clinical diagnosis of melanoma.

(ABCDE-rule).

Asymmetry - is when one-half of the lesion does not match the other half of lesion

Border irregularity - is when the edges are, notched, ragged or blurred

Color irregularity - pigmentation is not various colored pigmentation is seen ranging from black, brown, tan, red, blue and white

Diameter - more than 6 mm

Elevation - a rise in the surface is also sign.

Types of melanoma

Superficial spreading

Nodular melanoma

Lentigo maligna melanoma

Acral lentiginous melanoma

Mucosal lentiginous melanoma20.

Of these, acral lentiginous and mucosal lentiginous melanoma commonly occur in the oral cavity. Hard palate is the most commonly involved site where it presents as a brown to black macule with irregular borders.[22]

Conclusion

Pigmentation is defined as the process of deposition of pigments in tissues. Various diseases can lead to varied colorations in the mucosa. It can arise from intrinsic and extrinsic factors and can be physiological or pathological. The dentist should be aware of the various lesions to aid in the proper treatment plan.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Kauzman A, Pavone M, Blanas N, Bradley G. Pigmented lesions of the oral cavity: Review, differential diagnosis, and case presentations. J Can Dent Assoc. 2004;70:682–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenberg M, Glick M. Burkets oral medicine diagnosis and treatment. 10th ed. Hamilton, Ontario: B. C. Decker; 2003. pp. 126–36. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaeta GM, Satriano RA, Baroni A. Oral pigmented lesions. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:286–8. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(02)00225-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarswathi TR, Kumar SN, Kavitha KM. Oral melanin pigmentation in smoked and smokeless tobacco users in India. Clinico-pathological study. Indian J Dent Res. 2003;14:101–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eisen D. Disorders of pigmentation in the oral cavity. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:579–87. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(00)00148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrett AW, Scully C. Human oral mucosal melanocytes: A review. J Oral Pathol Med. 1994;23:97–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1994.tb01095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anil Kumar N, Divya P. Adverse drug effects in mouth. International Journal Of Medical And Applied Sciences. 2015;4:82–91. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reichert R, Philipsein HP. Betel chewers mucosa – A review. J Oral Pathol. 1976;5:229–36. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ, Jordan RC, editors. Oral Pathology. Clinical Pathologic Correlations. 5th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith KJ, Skelton HG, Yeager J, Ledsky R, McCarthy W, Baxter D, et al. Cutaneous findings in HIV-1-positive patients: A 42-month prospective study. Military Medical Consortium for the Advancement of Retroviral Research (MMCARR) J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:746–54. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70236-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanford JP, Favour CB. The interrelationships between Addison's disease and active tuberculosis: A review of 125 cases of Addison's disease. Ann Intern Med. 1956;45:56–72. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-45-1-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Betterle C, Greggio NA, Volpato M. Clinical review 93: Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1049–55. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.4.4682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier Publications: Elsevier Publications; 2009. pp. 308–13. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchner A, Hansen LS. Amalgam pigmentation (amalgam tattoo) of the oral mucosa. A clinicopathologic study of 268 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1980;49:139–47. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(80)90306-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Wayli H, Rastogi S, Verma N. Hereditary hemochromatosis of tongue. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amos CI, Keitheri-Cheteri MB, Sabripour M, Wei C, McGarrity TJ, Seldin MF, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. J Med Genet. 2004;41:327–33. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.010900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatch CL. Pigmented lesions of the oral cavity. Dent Clin North Am. 2005;49:185–201. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2004.07.013. ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhargava A, Saigal S. Laugier-hunziker syndrome: A review. Indian J Dent Sci. 2011;3:317. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bauer AJ, Stratakis CA. The lentiginoses: Cutaneous markers of systemic disease and a window to new aspects of tumourigenesis. J Med Genet. 2005;42:801–10. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.017806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naidu RM, Joshua E, Saraswathi T, Ranganathan K. Pigmentation of palatal mucosa due to trauma: A case report. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2002;1:34–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lakshminarayanan V, Ranganathan K. Oral melanoacanthoma: A case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:11. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-3-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barker BF, Carpenter WM, Daniels TE, Kahn MA, Leider AS, Lozada-Nur F, et al. Oral mucosal melanomas: The WESTOP Banff workshop proceedings. Western Society of Teachers of Oral Pathology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:672–9. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]