Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Curcumin is a naturally occurring anti-inflammatory agent with various biologic and medicinal properties. Its therapeutic applications have been studied in a variety of conditions, but only few studies have evaluated the efficacy of curcumin as local drug delivery agent and in the treatment of periodontitis. The present study was to evaluate the efficacy of the adjunctive use of curcumin with scaling/root planing as compared with scaling/root planing alone in the treatment of the chronic periodontitis.

Materials and Methods:

Thirty patients with two sites in the contralateral quadrants having probing pocket depths (PPDs) of ≥5 mm were selected. Full mouth scaling and root planing (SRP) was performed followed by application of curcumin gel on a single side. Assessment of plaque index (PI), gingival index (GI), PPD, and clinical attachment levels (CALs) were done at baseline and at 4th week. Microbiologic assessment with polymerase chain reaction was done for Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tanerella forsythia, and Treponema denticola by collection of plaque samples.

Results:

The results revealed that there was a reduction in PI, GI, probing depth, CAL, and microbiologic parameters in test sites following SRP and curcumin gel application, when compared with SRP alone in control group.

Conclusion:

The local application of curcumin in conjunction with scaling and root planing have showed improvement in periodontal parameters and has a beneficial effect in patients with chronic periodontitis.

KEY WORDS: Curcumin, periodontitis, polymerase chain reaction, scaling and root planing

Periodontitis is an infectious inflammatory disease of the supporting tissues of teeth and is one of the most common diseases encountered in humans.[1] It is a complex disease in which disease expression involves intricate interactions of the biofilm with host immunoinflammatory response and subsequent alterations in bone and connective tissue homeostasis.[2] Thus, there is an imbalance between bacterial virulence and host defense ability.[1] The progression of the disease is related to the colonization of chief microorganisms such as Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and Prevotella intermedia.[3]

Scaling and root planing (SRP) is one of the most commonly utilized procedures in the treatment of periodontal diseases and has been used as the “gold standard” for mechanical therapy.[4] Data have demonstrated that scaling and root planing alone has limited effect on some pathogenic species, and that the total eradication of subgingival bacteria is often not achieved. This may be due to the fact that some of these species can reside in soft tissues, dentinal tubules, or in root surface irregularities, thereby contributing to treatment failure.[5]

To overcome the limitations of this conventional treatment, antibiotics and antiseptics have been used successfully to treat moderate to severe periodontal disease by systemic and local administration. However, systemic antibiotics require the administration of large dosages to obtain suitable concentrations at the site of disease, which could potentially promote the development of bacterial resistance, side effects, drug interactions, and inconsistent patient compliance. To avoid these limitations of systemic administration, a different approach has been introduced that uses local delivery systems that contain antibiotic or antiseptic agents.[6]

Local delivery of chemotherapeutic agents into the pockets via a syringe or irrigating device has been shown to be effective against subgingival flora.[7] The clinical efficacy of a local drug delivered is to be evaluated primarily by using several outcome measures: Reduced probing depths (PD), increased clinical attachment levels (CALs), decreased bleeding on probing, and reduced disease progression.[8] In order to accomplish this, local application of pharmacological agents must fulfill three criteria:

The medication must reach the intended site of action

Remain at an adequate concentration; and

Last for a sufficient duration of time.[8]

Turmeric (the common name for Curcuma longa) is an Indian spice derived from the rhizomes, a perennial member of the Zingiberaceae family.[9] The Latin name is derived from the Persian word, “kirkum”, which means saffron.[10] The primary active constituent of turmeric and the one responsible for its vibrant yellow color is “curcumin” first identified in 1910 by Lampe and Milobedzka.[9]

The active constituents of turmeric include the three curcuminoids: Curcumin (diferuloylmethane), demethoxycurcumin, and bisdemethoxycurcumin, as well as volatile oils (turmerone, atlantone, and zingiberone), sugars, proteins, and resins.[9] Curcumin exhibits anti- inflammatory, antioxidant, anticarcinogenic, antiviral, and antimicrobial activities. Curcumin modulates the inflammatory response by down-regulating the activity of cyclooxygenase-2, lipoxygenase, and inducible nitric oxide synthase enzymes and inhibits the production of the inflammatory cytokines.[9]

This study is designed to evaluate the efficacy of local drug delivery with curcumin, which is a common antiseptic used in traditional system of Indian medicine, post scaling and root planing and its effect on clinical parameters like plaque, gingival scores and pocket PD and CAL and its efficacy in suppressing the pathogenic anaerobic microflora by microbiologic analysis using polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Materials and Methods

This was a randomized split mouth, single-blinded study undertaken to evaluate the effect of curcumin as an adjunct to SRP. The study population included 30 patients aged 35–60 reported to the Department of Periodontics, St. Joseph Dental College, Eluru between June 2012 and June 2013 and were subsequently diagnosed as chronic periodontitis patients. Approval of the study was obtained from the ethical committee of St. Joseph Dental College and an informed consent was taken from all participants before commencing of the study.

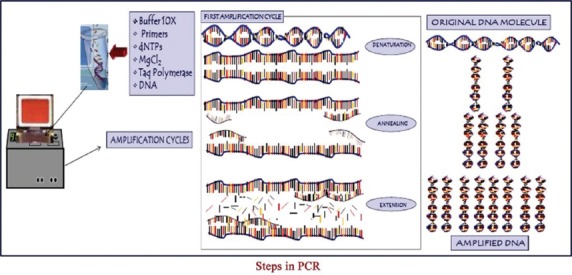

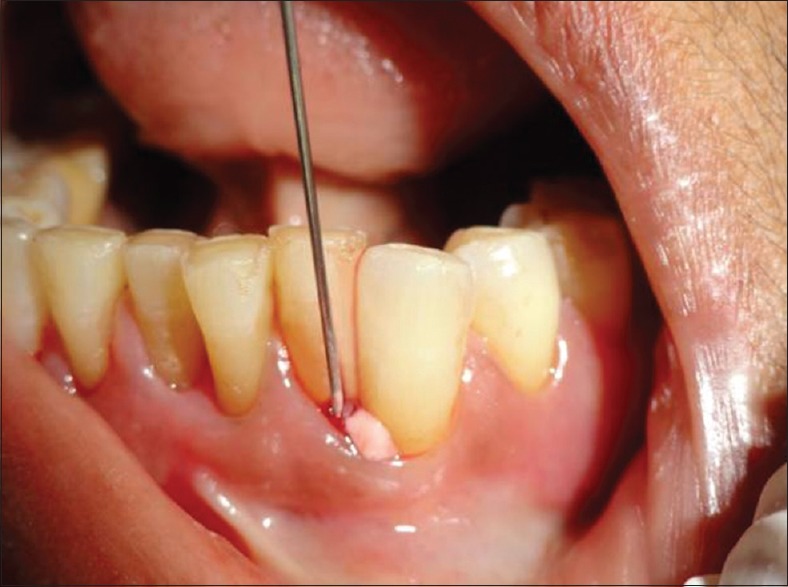

Clinical parameters measurement was done in probing pocket depth (PPD) of 5 mm or greater at baseline [Figure 1] and after 4 weeks along with microbiologic analysis of subgingival plaque samples [Figure 2] for the “red complex” periodontal pathogens using PCR [Figure 3].

Figure 1.

Probing depth is measured with Williams graduated Periodontal Probe

Figure 2.

Subgingival plaque sample is collected by using Gracey curette

Figure 3.

Steps in polymerase chain reaction

Inclusion criteria

Patients willing to take part in the study

Subjects in the age group >35 years without ant systemic disease

Patients who have test teeth with both mesial and distal neighboring teeth

Patient with more than 16 natural teeth

Patient with chronic periodontitis having a PPD of >5 mm and radiographic evidence of bone loss

Patients with no history of allergies.

Exclusion criteria

Pregnant woman and lactating mothers

Teeth with both endo-perio lesion

Patient with use of tobacco or tobacco related products

Patient on antibiotics within 3 months prior to study

Patients having systemic diseases like diabetes mellitus, hypertension, bleeding disorders, hyperparathyroidism, and compromised medical conditions

Patients who have had periodontal treatment in last 6 months

Patients who underwent periodontal surgery, restorative procedures, and tooth extraction adjacent to either of test area in the previous 3 months

Long-term therapy with medications within a month prior to enrollment that could affect periodontal status or healing

Patients medical or dental therapy that could have an impact on the subjects ability to complete the study.

Two sites were identified for the study in each patient and were randomly allocated by coin toss:

Group I (control) - Only scaling and root planing was done at the baseline visit

Group II (test) - Scaling and root planing was followed by local application of curcumin at the baseline visit.

The parameters recorded were plaque index (PI) (Silness and Loe, 1964), GI (Loe and Silness, 1963), PD, CAL. Subgingival plaque samples will be collected by using a Gracey curette by inserting it subgingivally into the deepest portion of the periodontal pocket parallel to the long axis of the tooth and moved coronally by scraping along the root surface. The microbial samples were stored in Tris- EDTA medium and sent for performing polymerase chain reaction using multiplex PCR apparatus.

Curenext oral gel 10g (ayurvedic proprietary medicine) containing C. longa extract manufactured by Abbott Healthcare Pvt. Ltd., 4. Corporate Park, Sion Trombay Road, Chembur, Mumbai 400 071, India. Mfg. Lic. No.: NK/AYU/006-A/10 was taken. It was dispensed subgingivally to base of pocket by means of a disposable syringe in the test site [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Curcumin gel placement

Results

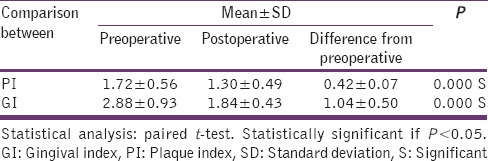

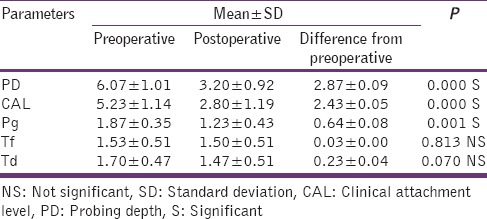

An interventional split-mouth study in 30 patients (18 females and 12 males) with mean age of 38 ± 4 was conducted over a period of 4 weeks. There was a significant reduction in PI values from baseline to follow-up visit (P = 0.000). There was a significant reduction in GI scores in this study (P = 0.001). This may be due to the elimination of local etiologic factors (plaque and calculus) which harbor numerous pathogenic bacterial strains [Table 1].

Table 1.

PI and GI

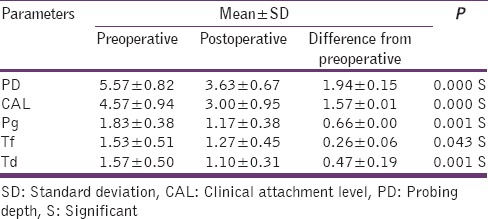

The difference in mean PPD reductions was significant (P = 0.042) at test site when compared to the control site. There was a slight but not statistically significant reduction (P = 0.473) in mean CAL levels in test than in control group. [Tables 2 and 3].

Table 2.

Clinical and microbiological parameters in control group

Table 3.

Clinical and microbiological parameters in test group

The microbiologic essay (PCR) has shown a proportionate reduction in P. gingivalis, Tanerella forsythia, Treponema denticola in test and control group [Tables 2 and 3]. PI, GI, clinical, and microbiological parameters in both control and test group are discussed in the following tables from Tables 1–3.

Discussion

An interventional split-mouth study in 30 patients (18 females and 12 males) with mean age of 38 ± 4 was conducted over a period of 4 weeks. There was a significant reduction in PI values from baseline to follow-up visit (P = 0.000). This can be attributed to the fact that there was a reduction in supragingival plaque after SRP and oral hygiene instructions received during the preliminary visit. The results of this study were consistent with Paolantonio et al.,[6] Cugini et al.[4] There was a significant reduction in GI scores in this study (P = 0.001). This may be due to the elimination of local etiologic factors (plaque and calculus) which harbor numerous pathogenic bacterial strains. This was in accordance with Hinrichs et al.[11] and Cugini et al.[4]

The difference in mean PPD reductions was significant (P = 0.042) at test site when compared to the control site. This can be attributed to anti-inflammatory mechanism of curcumin which modulates the inflammatory response, inhibits the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, represses the activation of AP-1 and NF-kβ, inhibit the biosynthesis of inflammatory prostaglandins enhances neutrophil function during inflammatory response. This was in good agreement with the study reported by Jurenka,[9] Chainani-Wu,[12] Menon and Sudheer,[13] Akram et al.[14] It may also be due to the effectiveness of SRP in overall gain of periodontal attachment as well as decrease in percent of sites with supragingival biofilm accumulation and gingival inflammation. This finding was in accordance with Colombo et al.[5]

There was a slight but not statistically significant reduction (P = 0.473) in mean CAL levels in test than in control group. It may be due to increased levels of transforming growth factor-β1 in healing tissue, earlier re-epithelialization, improved neovascularization, reduced inflammatory cell infiltrate, increased collagen content and fibroblastic cell numbers, enhanced wound repair in sites treated with curcumin. This was in accordance to studies done by Habiboallah et al.[15] Guimarães et al.[16] The reduction in mean CALs in the control group was in accordance with the studies by Colombo et al.[5] Meinberg et al.[17] Cugini et al.[4]

The microbiologic essay (PCR) has shown a proportionate reduction in P. gingivalis, T. forsythia, T. denticola in test and control group. The significant reduction could be because of the antibacterial, anti-inflammatory and antiplaque activity of curcumin. It also shows a favorable reduction of trypsin-like enzyme activity of microorganisms associated with periodontal disease. This was in accordance with studies by Behal et al.[18]

Thus, the inhibitory effects of curcumin support its utility as a prophylactic and therapeutic agent for inflammatory bone diseases such as periodontitis. To further elucidate the use of this local delivery system, a long-term study with large sample of subjects should be carried out.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Kou Y, Inaba H, Kato T, Tagashira M, Honma D, Kanda T, et al. Inflammatory responses of gingival epithelial cells stimulated with Porphyromonas gingivalis vesicles are inhibited by hop-associated polyphenols. J Periodontol. 2008;79:174–80. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kornman KS. Mapping the pathogenesis of periodontitis: A new look. J Periodontol. 2008;79(8 Suppl):1560–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.080213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mizrak T, Güncü GN, Caglayan F, Balci TA, Aktar GS, Ipek F. Effect of a controlled-release chlorhexidine chip on clinical and microbiological parameters and prostaglandin E2 levels in gingival crevicular fluid. J Periodontol. 2006;77:437–43. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cugini MA, Haffajee AD, Smith C, Kent RL, Jr, Socransky SS. The effect of scaling and root planing on the clinical and microbiological parameters of periodontal diseases: 12-month results. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:30–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027001030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colombo AP, Teles RP, Torres MC, Rosalém W, Mendes MC, Souto RM, et al. Effects of non-surgical mechanical therapy on the subgingival microbiota of Brazilians with untreated chronic periodontitis: 9-month results. J Periodontol. 2005;76:778–84. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.5.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paolantonio M, D’Angelo M, Grassi RF, Perinetti G, Piccolomini R, Pizzo G, et al. Clinical and microbiologic effects of subgingival controlled-release delivery of chlorhexidine chip in the treatment of periodontitis: A multicenter study. J Periodontol. 2008;79:271–82. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soskolne WA. Subgingival delivery of therapeutic agents in the treatment of periodontal diseases. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1997;8:164–74. doi: 10.1177/10454411970080020501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenstein G, Tonetti M. The role of controlled drug delivery for periodontitis. The Research, Science and Therapy Committee of the American Academy of Periodontology. J Periodontol. 2000;71:125–40. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jurenka JS. Anti-inflammatory properties of curcumin, a major constituent of Curcuma longa: A review of preclinical and clinical research. Altern Med Rev. 2009;14:141–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaturvedi TP. Uses of turmeric in dentistry: An update. Indian J Dent Res. 2009;20:107–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.49065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hinrichs JE, Wolff LF, Pihlstrom BL, Schaffer EM, Liljemark WF, Bandt CL. Effects of scaling and root planing on subgingival microbial proportions standardized in terms of their naturally occurring distribution. J Periodontol. 1985;56:187–94. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.4.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chainani-Wu N. Safety and anti-inflammatory activity of curcumin: A component of tumeric (Curcuma longa) J Altern Complement Med. 2003;9:161–8. doi: 10.1089/107555303321223035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menon VP, Sudheer AR. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of curcumin. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;595:105–25. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-46401-5_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akram M, Uddin S, Afzal A, Usmanghani K, Hannan A, Mohiuddin E, et al. Curcuma longa and curcumin: A review article. Rom J Biol Plant Biol. 2010;55:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Habiboallah G, Nasroallah S, Mahdi Z, Nasser MS, Massoud Z, Ehsan BN, et al. Histological evaluation of Curcuma longa-ghee formulation and hyaluronic acid on gingival healing in dog. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;120:335–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guimarães MR, Coimbra LS, de Aquino SG, Spolidorio LC, Kirkwood KL, Rossa C., Jr Potent anti-inflammatory effects of systemically administered curcumin modulate periodontal disease in vivo. J Periodontal Res. 2011;46:269–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2010.01342.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meinberg TA, Barnes CM, Dunning DG, Reinhardt RA. Comparison of conventional periodontal maintenance versus scaling and root planing with subgingival minocycline. J Periodontol. 2002;73:167–72. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Behal R, Mali AM, Gilda SS, Paradkar AR. Evaluation of local drug-delivery system containing 2% whole turmeric gel used as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in chronic periodontitis: A clinical and microbiological study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2011;15:35–8. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.82264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]