Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a major public health challenge. Unjustified calls for the isolation of patients with HIV infection might further constrain the potential for expansion of clinical services to deal with a greater number of such patients. This infectious illness can evoke irrational emotions and fears in health care providers. Keeping this in view, a study was conducted to assess the knowledge and attitudes related to HIV/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) among dental and medical students.

Methodology:

Descriptive cross-sectional survey of the entire dental and medical undergraduate students from two colleges was carried out using a pretested, self-administered questionnaire. Descriptive statistics such as percentage was used to present the data.

Results:

Ninety-eight percentage medical and dental undergraduate graduate students knew about HIV transmission in the hospital. Journals and internet were the leading source of information among both medical and dental undergraduates. The majority of respondents discussed HIV-related issues with their classmates. Surprisingly, 38% medical and 52% dental undergraduates think that HIV patient should be quarantined (isolation) to prevent the spread of infection. 68% medical and 60% dental undergraduates are willing to rendering dental/medical care to HIV-infected patients. Relatively large proportion (98%) of participants was willing to participate for HIV prevention program.

Conclusion:

The knowledge of medical and dental students is adequate, but the attitude needs improvement. Dental and medical students constitute a useful public health education resource. Comprehensive training, continuing education, and motivation will improve their knowledge and attitude, which enable them to provide better care to HIV patients.

KEY WORDS: Attitude, human immunodeficiency virus, knowledge

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a major public health challenge with an estimated 2.24 million persons living with HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) people living with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (PLWHA) in India. On the Asian sub-continent, an estimated 4.87 million people were living with HIV in 2009.[1]

In India, as in many other countries, people with HIV frequently encounter discrimination, while seeking and receiving health care services, with serious adverse consequences for their physical and psycho-social well-being. Unjustified calls for the isolation of patients with HIV infection might further constrain the potential for expansion of clinical services to deal with a greater number of such patients. This infectious illness can evoke irrational emotions and fears in health care providers, including medical students. If unexamined, these fears may produce a barrier to successful educational efforts about HIV/AIDS and result in a variety of adverse outcomes. HIV/AIDS has stimulated ethical debates about a physician's right to refuse treatment. While there is a risk of transmission of the virus from patient to health care worker, this risk has been estimated at 0.3% after a single percutaneous exposure to HIV/AIDS-infected blood.[2]

Medical students have refused to care for HIV/AIDS patients,[3] which is unacceptable for future physicians and illustrates the extreme emotions. Oral health issues have been identified as a significant health issue in HIV-infected individuals.[4,5,6] Oral manifestations of HIV/AIDS, such as thrush, warts, periodontal diseases and rapidly progressing dental decay, occur in a very high percentage of people living with HIV/AIDS.[7] HIV-infected patients, with or without knowledge of their own serologic status are seeking dental care in increasing numbers.[8,9] Oral health care in HIV-infected individual plays a vital role in improving nutritional intake.[10]

An improvement in the oral health of HIV-positive individuals has been reported to be significantly associated with improvements in both physical and mental health.[11]

Although reasonable numbers of oral health care practitioners in some parts of the world remain unwilling to render care to this patient group.[12,13] The knowledge and attitude of health workers in relation to HIV is an important determinant of their willingness to care and the quality of the care they will render to HIV patient. Insufficient knowledge might cause negative attitude toward HIV-positive patients. The link between increased knowledge of the disease and improved attitudes towards patients with HIV/AIDS has been documented.[14]

However, there are few studies which have explored knowledge and attitudes of dental and medical students pertaining to HIV/AIDS, particularly in the southern part of India. Keeping this in view, a study was conducted to assess the knowledge and attitudes related to HIV/AIDS among dental/medical students in Raichur.

Methodology

A descriptive cross-sectional survey of the entire dental and medical undergraduate students from two colleges of Raichur was carried out. Data were collected using a pretested, self-administered questionnaire. This well-structured, questionnaire elicited information on demographic characteristics, HIV/AIDS knowledge, source of information, interpersonal communication concerning HIV, attitudes toward HIV testing and PLWHA, occupational risk perception/precautions, willingness to care for HIV-infected people. Informed consent was obtained prior to the administration of the questionnaire. Participation was voluntary, participants were educated on the aim of the survey, assured of the strict confidentiality of their responses. The students who are in clinical postings were included in the study.

Data analysis was done using 2004 version of the general social survey (GSS), statistical package of social sciences for Windows 13.o, (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Descriptive statistics such as percentage was used to present the data.

Results

As shown in Table 1, a total of 425 subjects took part in the study, and many of respondents were in the age range of 18–26 years. The study population consisted of 280 medical students’ and 145 dental students.

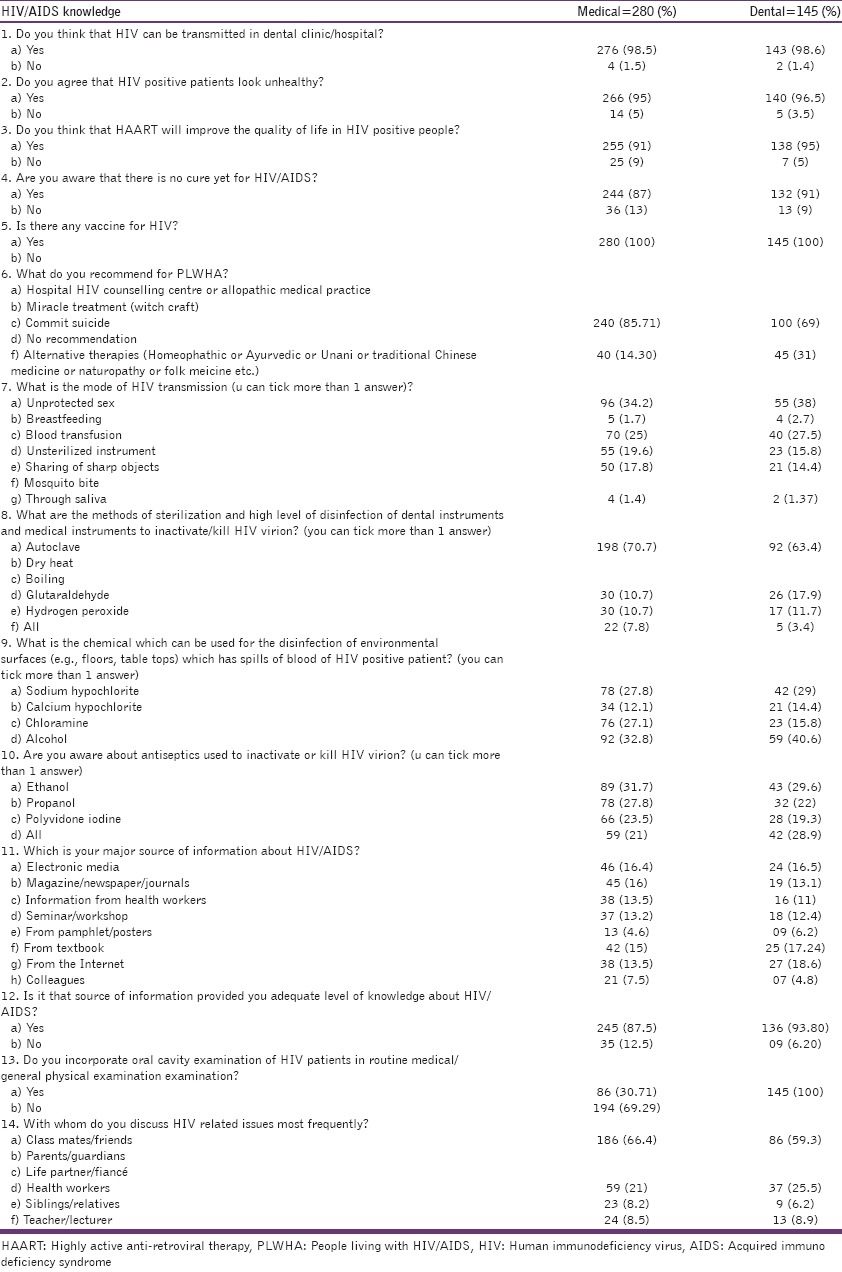

Table 1.

Knowledge of HIV among medical and dental students

Knowledge of human immunodeficiency virus among medical students

Majority (98.5%) surveyed respondents knew about HIV transmission in the hospital while only 1.5% responded HIV transmission do not occur in a hospital. 95% believe that HIV positive patients look unhealthy while few (5%) said they will look healthy. 91% respondents indicated that highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) will improve the quality of life in HIV-positive people, only 9% said it will not improve the quality of life. 87% subjects has opinion that there is no cure for HIV/AIDS remaining 13% said there is a cure for HIV/AIDS. All respondents confidently said there is no vaccination for HIV. 85% respondents recommended the allopathic medical practice for PLWHA while few recommended other alternative therapies (Homeopathic or Ayurvedic or Unani or Traditional Chinese Medicine or Naturopathy). Regarding mode of transmission, 34.2% said it's due to unprotected sex, 25% indicated blood transfusion, 19.6% opted unsterilized instrument, 17.8% expressed its due to sharing of sharp objects, 1.7% said due to breastfeeding, 1.4% through saliva, many said combination of all and none preferred the option mosquito bite. For sterilization and a high level of disinfection of medical instruments (equipments) to inactivate/kill HIV virion, the majority of respondents (70.7%) preferred autoclaving, followed by glutaraldehyde disinfectant, hydrogen peroxide. None of the respondents opted for drying and boiling while 7.8% indicated all the above methods. For the disinfection of environmental surfaces (e.g., floors, table tops), which has spills of blood of HIV positive patient, 32.8% opted alcohol, followed by 27.8% sodium hypochlorite, 7.1% chloramine, and 12.1% calcium hypochlorite. 31.7% respondents preferred ethanol as antiseptics to kill HIV virion, 27.8% indicated propanol, 23.5% said polyvidone iodine and remaining 21% picked the option all of above antiseptics. 16.4% indicated electronic media as a major source of information, while many said a combination of internet, newspapers, magazines, journals, seminars, workshops, pamplets, posters and information from health workers. The majority of respondents (87.5%) said the above sources provided adequate knowledge about HIV only few (12.5%) said the sources were not enough for providing HIV knowledge. The majority of the respondents (69.29%) never incorporated oral cavity examination of HIV patients in routine medical/physical examination only few (30.71%) incorporated it. The majority of respondents (66.4%) discussed HIV-related issues with their classmates while 21% discussed with health workers, 8.5% with teachers and 8.2% with siblings/relatives [Table 1].

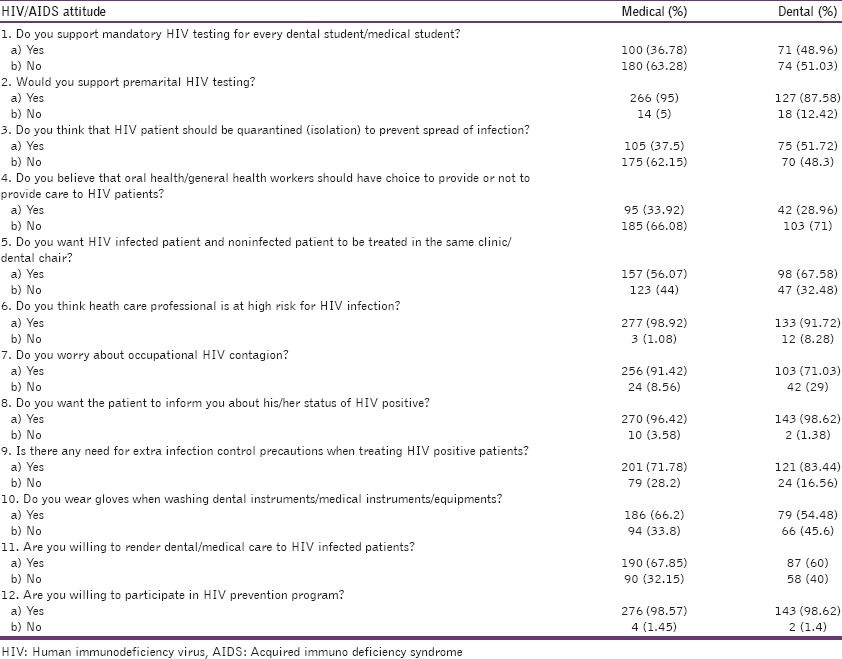

Attitudes of medical students

Some of the respondents (36%) think that HIV testing should be mandatory for every dental student/medical student while very majority (64%) expressed it's not necessary. 95% respondents are in support premarital HIV testing, only few (5%) decline premarital HIV testing. Surprisingly, few respondents (37%) think that HIV patient should be quarantined (isolation) to prevent the spread of infection, and 63% said need not to be quarantined. 33% believe that oral health/general health workers should be allowed to choose whether or not to provide care to HIV patients. While large proportion (67%) claims that oral health/general/health workers should not be allowed to choose whether or not to provide care to HIV patients. More than 50% respondents prefer to treat HIV-infected patient and non-infected patient in the same dental clinic/chair while less than 50% did not prefer to treat infected and non-infected in the same dental chair clinic. 99% respondents agreed that heath care professional was at high-risk group for HIV infection. 92% respondents worried about occupational HIV contagion while few (8%) not worried about occupational HIV contagion. 97% participants expect the patient to inform the doctor about his/her status of HIV positive while few believed it to be kept confidential. 72% respondents believe that there is a need for extra infection control precautions when treating HIV-positive patients, only 29% disagreed for that. 67% participants always use gloves while cleaning instruments (equipments), 33% did not use gloves while washing instruments. 68% participants are willing to participate in rendering dental/medical care to HIV-infected patients while remaining 33% were unwilling. Almost all (99%) subjects are willing to participate for HIV prevention program just small proportions (1%) were unwilling [Table 2].

Table 2.

Attitudes of medical and dental students

Knowledge of dental students

Majority (98.6%) surveyed respondents knew about HIV transmission in the hospital while only 1.4% responded HIV transmission do not occur in a hospital. 96.5% believe that HIV-positive patients look unhealthy while few (3.5%) said they will be healthy. 95% respondents indicated that HAART will improve the quality of life in HIV-positive people, only 5% said it will not improve quality of life. 91% subjects has the opinion that there is no cure for HIV/AIDS remaining 9% said there is a cure for HIV/AIDS. All respondents confidently said there is no vaccination for HIV. 69% respondents recommended the allopathic medical practice for PLWHA while few (31%) recommended other alternative therapies (Homeopathic or Ayurvedic or Unani or Traditional Chinese Medicine or Naturopathy). Regarding mode of transmission 38% said it's due to unprotected sex, 27.5% indicated blood transfusion, 15.8% opted unsterilized instrument, 14.4% sharing of sharp objects, 2.7% breastfeeding, 1.3% through saliva, and none preferred the option mosquito bite. For sterilization and a high level of disinfection of dental instruments to inactivate/kill HIV virion majority of respondents (63.4%) preferred autoclaving, followed by glutaraldehyde disinfectant, hydrogen peroxide. None of the respondents opted for drying and boiling while 3.4% indicated all the above methods. For the disinfection of environmental surfaces (e.g., floors, table tops) which has spills of blood of HIV positive patient, 40.6% opted alcohol, followed by 29% sodium hypochlorite, 15.8% chloramine, and 14.4% calcium hypochlorite. 29.6% respondents preferred ethanol as antiseptics to kill HIV virion, 22% indicated propanol, 19.3% said polyvidone iodine and remaining 28.9% picked the option all of the above antiseptics. 18.6% indicated internet as a major source of information, while 17.4% said textbooks, 16.5% electronic media and many said a combination of internet, newspapers, magazines, journals, seminars, workshops, pamphlets, posters and information from health workers being their major source of information. The majority of respondents (93.8%) said the above sources provided adequate knowledge about HIV only few (6.2%) said the sources were not enough for providing HIV knowledge. All of the respondents (100%) incorporated oral cavity examination of HIV patients in routine medical/physical examination. The majority of respondents (59.3%) discussed HIV-related issues with their classmates while 25.5% discussed with health workers, 8.9% with teachers and 6.2% with siblings/relatives [Table 1].

Attitudes of dental students

Nearly 50% of respondents think that HIV testing should be mandatory for every dental student/medical student while remaining 50% expressed it is not necessary. 95% respondents are in support premarital HIV testing; only few (5%) decline premarital HIV testing. Surprisingly, 50% respondents think that HIV patient should be quarantined (isolation) to prevent spread of infection and remaining 50% said need not. 29% believe that oral health/general health workers should be allowed to choose whether or not to provide care to HIV patients. While large proportion (71%) claim that oral health/general health workers should not be allowed to choose whether or not to provide care to HIV patients. More than 60% respondents prefer to treat HIV-infected patient and non-infected patient in the same dental clinic/chair while less than 40% did not prefer to treat infected and non-infected in the same dental chair/clinic. 91% respondents agreed that heath care professional was at high-risk group for HIV infection. 71% respondents worried about occupational HIV contagion while few (29%) not worried about occupational HIV contagion. 97% participants expect the patient to inform the doctor about his/her status of HIV positive while few believed to be kept confidential. 83% respondents believe that there is a need for extra infection control precautions when treating HIV-positive patients, only 17% disagreed for that. 54% of respondents always use gloves when washing dental instruments, 46% did not use gloves while washing instruments. 60% are willing to participate in rendering dental/medical care to HIV-infected patients while remaining 33% were unwilling. Almost all (99%) respondents were willing to participate for HIV prevention program just small proportions (1%) were unwilling.

Discussion

This study assessed the level of knowledge and attitudes of dental/medical students towards HIV/AIDS.

Human immunodeficiency virus and AIDS are widely spread infectious diseases, and the number of people living with HIV worldwide has continued to increase, reaching an estimated 33.4 million. Compared to 1990, the total number of people living with the virus in 2008 was approximately threefold higher.[15]

This study showed that the level of knowledge among dental and medical students was high, indicating a better understanding of the mechanisms involved in HIV infection. Medical students have the slightly better knowledge, and attitude compare to dental students. However, few of the respondents did not know that the viral load in saliva and breast milk is very low that it cannot transmit the HIV. Dental students who routinely deal with patients’ saliva tend to be unwilling to treat PLWHA. Therefore, it is important for dental care workers to be well equipped with up-to-date information about different routes of HIV transmission.

The risk of transmission of the virus from patient to health care worker has been estimated at 0.3% after a single percutaneous exposure to HIV/AIDS-infected blood.[2]

In our study, majority of respondents think that health care professionals are at high risk of exposure to HIV. The chances for health care professionals to encounter PLWHA in clinics/hospitals are high. Hence, they should be well prepared with accurate knowledge and positive attitude. Some of the respondents think that HIV testing should be mandatory for every dental student/medical student. Approximately, 90% respondents are in support premarital HIV testing. This is a debatable issue because the choice of individual to undergo HIV testing is his discretionary and since there are no Indian government policies/laws about compulsory HIV testing. It is a difficult task to convince all persons to undergo HIV testing.

Due to recent advances in treatment strategies, HIV infection has been transformed from a fatal and terminal disease into a chronic illness requiring constant management and regular monitoring. However, many respondents answered that they want the isolation of HIV patients in order to prevent the spread of infection but the fact is HIV cannot spread through air, saliva or breast milk. The negative perception of HIV/AIDS is still dominant among dental/medical students despite adequate knowledge about HIV/AIDS. Irrational fears among health care professionals may produce a barrier to successful treatment for HIV-infected patients around 30% respondents are not wearing gloves while washing instruments which is a major concern. HIV cannot spread easily but once the person is infected there is no cure yet for this disease. So students should be very careful in handling the instruments. Many of the respondents are willing to participate in HIV preventive program, which might further improve the potential for expansion of preventive services to people at large. Nearly 40% of respondents are unwilling to render medical/dental care to HIV-infected persons, which show their negative attitude in spite of adequate knowledge. In our study, approximately one-third of medical and dental students believe that oral health/general health workers should be allowed to choose whether or not to provide care to HIV patients. A health care professional's right to refuse treatment for HIV/AIDS patients is unjustified and may trigger an unwarranted ethical debate. The due care for HIV-infected patients is not related to level of knowledge because our study proved that in spite of high knowledge about HIV/AIDS still there exists certain misconceptions among health care professionals about HIV/AIDS which should be done away with proper education and self-motivation.

In our findings medical and dental student's perception is negative despite adequate knowledge. Regular seminars, continuing dental/medical education and motivation would help dental/medical students to change their negative attitudes toward PLWHA.

Conclusion

As per our study, medical students had little better knowledge and attitude compared to dental students. The overall knowledge of both medical and dental undergraduate students is adequate but needs further improvement. The attitude in medical and dental students is inadequate needs to be improved in a greater degree. Health care professional's knowledge and attitude are an important determining factor to provide proper care and deliver quality treatment to HIV patient. Dental and medical students constitute a useful public health education resource. Inadequate knowledge and irrational fear about HIV might cause negative attitude toward HIV positive patients. Comprehensive training, education and motivation through continuing dental/medical education will improve their knowledge and attitude, which enable them to render much better treatment to HIV-infected patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.UNDP in India: Results from 2010. Empowered lives. Resilient Nations. [Last cited on 2011 Sep 19]. Available from: http://www.undp.org.in/sites/default/files/reports_publication/UNDP_Annual_Report_2011.pdf .

- 2.Fauci AS, Harrison CL. Harrisons principles of internal medicine. 16th ed. New York: Mc Graw Hill publisher; 2003. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease: AIDS and related disorders; pp. 1076–139. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whalen JP. Participation of medical students in the care of patients with AIDS. J Med Educ. 1987;62:53–4. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198701000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epidemiologic aspects of the current outbreak of Kaposi's sarcoma and opportunistic infections. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:248–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198201283060431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tavitian A, Raufman JP, Rosenthal LE. Oral candidiasis as a marker for esophageal candidiasis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:54–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-104-1-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capilouto EI, Piette J, White BA, Fleishman J. Perceived need for dental care among persons living with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Med Care. 1991;29:745–54. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199108000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patton LL, McKaig R, Strauss R, Rogers D, Eron JJ., Jr Changing prevalence of oral manifestations of human immuno-deficiency virus in the era of protease inhibitor therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89:299–304. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(00)70092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silverman S., Jr The impact of HIV and AIDS on dentistry in the next decade. J Calif Dent Assoc. 1996;24:53–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patton LL. HIV disease. Dent Clin North Am. 2003;47:467–92. doi: 10.1016/s0011-8532(03)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel ASH, Hansen HJ. Oral health in human immunodeficiency virus patients. Top Clin Nutr. 2005;20:243–51. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coulter ID, Heslin KC, Marcus M, Hays RD, Freed J, Der-Martirosia C, et al. Associations of self-reported oral health with physical and mental health in a nationally representative sample of HIV persons receiving medical care. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:57–70. doi: 10.1023/a:1014443418737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Maaytah M, Al Kayed A, Al Qudah M, Al Ahmad H, Moutasim K, Jerjes W, et al. Willingness of dentists in Jordan to treat HIV-infected patients. Oral Dis. 2005;11:318–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crossley ML. A qualitative exploration of dental practitioners’ knowledge, attitudes and practices towards HIV+ and patients with other ‘high risk’ groups. Br Dent J. 2004;197:21–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4811412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wertz DC, Sorenson JR, Liebling L, Kessler L, Heeren TC. Knowledge and attitudes of AIDS health care providers before and after education programs. Public Health Rep. 1987;102:248–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geneva: UNAIDS; 2009. UNAIDS. UNAIDS Report on the Global HIV/AIDS Epidemic 2009. [Google Scholar]