Abstract

Invasive cervical resorption is often not diagnosed properly, leading to improper treatment or unnecessary loss of the tooth structure. Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment are the keys to a successful outcome of therapy. Invasive cervical resorption is often seen in the cervical area of the tooth, but because it is initiated apical to the epithelial attachment, it can present anywhere in the root. In the early stages, it may be symmetrical, but larger lesions have the tendency to be asymmetrical. It can expand apically or coronally.

KEY WORDS: Carnoy's solution, dental trauma, external resorption, invasive cervical resorption

Invasive cervical resorption (ICR) is a type of external root resorption which is characterized by invasion of root dentin by fibrovascular tissue derived from the periodontal ligament (PDL) as a result of odontoclastic action (irreversible damage). ICR usually starts from the cervical cement-enamel junction where the epithelial attachment is located and irrelevant to bacterial infections until secondary invasion from gingival sulcus occurs.[1]

This form of external resorption has been described at length by Heithersay, who preferred the term ICR, which is invasive and aggressive in nature. Some other terms used to describe external cervical resorption (ECR) are peripheral cervical resorption,[2] peripheral inflammatory root resorption,[3] extracanal invasive resorption,[4] supraosseous extracanal invasive resorption,[5] and subepithelial external root resorption,[6] odontoclastoma.[7]

Heithersay wrote a classic series of articles in which he described the features, possible predisposing factors and recommended treatment regimen for ICR. He described his treatment regimen, which included mechanical and chemical debridement of the resorptive lesions, followed by restoration and analyzed the treatment results.

Case Report

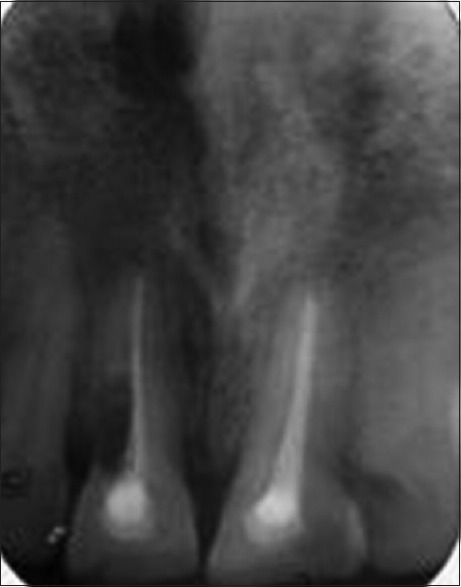

A 43-year-old male reported to the Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics with complaints of pain in 22 for the past 2 weeks. Pain throbbing in nature and continuous in character. Patient had a history of trauma before 10 years and he undergone RCT in 11, 21 [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Preoperative photograph

Clinical examination

Twenty-two shows a positive response to percussion and palpation with grade 1 mobility. 11, 21 shows a negative response to percussion, palpation. Pulp vitality test (thermal, electric pulp testing) shows negative response in 11, 21, 22 [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Intra oral view

Radiographic examination

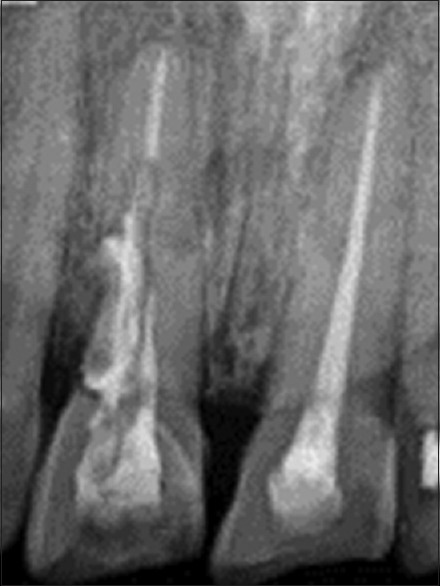

On radiographic examination 22 revealed pulp exposure with loss of laminadura and root canal treated 11 and 21 with a radiolucent region from cervical one-third to middle one-third on the distal aspect of crown of maxillary right central incisor (11) [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Preoperative radiograph

Radiographic appearance of the right maxillary central incisor reveals an irregular “mouth-eaten” radiolucency on the distal aspect of the tooth extending to the outline of the root canal and into the root.[8]

Treatment

The patient's preference was to save the tooth if possible.

Treatment plan

Emergency endodontic management of 22

Arrest resorptive process of 11

Restore damaged root surface of 11.

First visit

Root canal treatment of 22 initiated after cleaning and shaping calcium hydroxide with saline given as intracanal medicament.

In second visit

A labial flap was reflected, the lesion is accessed externally and debrided with a carbide round bur in a slow-speed handpiece. All the obvious resorptive tissue is removed until smooth, clean dentin is present, except a few small spots that are discolored or bleeding, which represent the communication of the resorption with the PDL.

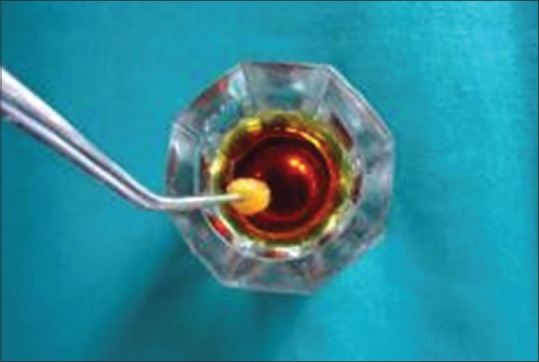

The dentin is then scrubbed for 1-min with Carnoy's solution on a cotton ball. Carnoy's solution is very caustic and cauterizes the residual resorptive tissue, which makes it more obvious under magnification. Additional tooth structure is removed carefully with a slow-speed round bur, and the acid is applied again. This process is continued until all the penetration points are eliminated in the surgical approach [Figures 4–6].

Figure 4.

Carnoy's solution

Figure 6.

Carnoy's solution on a cotton ball

Figure 5.

Full thickness flap elevated

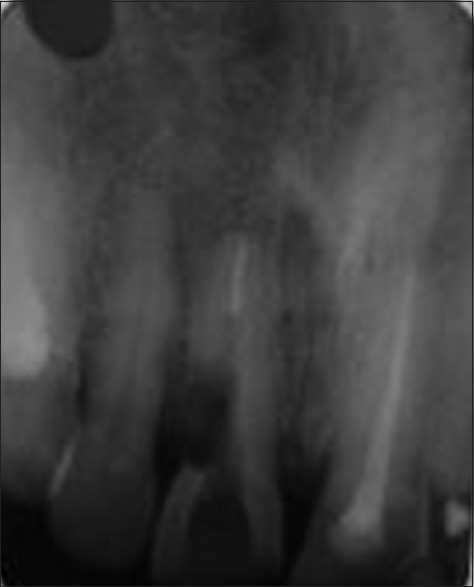

A small amount of alveolar bone was removed in the cervical area on the labial aspect of the tooth [Figure 7]. A postspace was created with gates glidden drills, and a glass fiber post was cemented with dual cure resin cement. The tooth was restored with an “open sandwich” technique. The dentin was conditioned with 10% polyacrylic acid for 15 s and after dentin bonding agent application flowable composite was used to restore the majority of the preparation [Figures 8–10].

Figure 7.

After debridement

Figure 8.

Postspace preparation

Figure 10.

Intra oral peri-apical radiograph after fibre postcementation

Figure 9.

Cementation of fibre post

The surgical area was subsequently rinse with sterile saline solution and dried with sterile gauze. White mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) was prepared following the manufacturer's instructions and placed to seal the root canal and the resorptive cavity. The flap was sutured in place with nonabsorbable suture, and postsurgical instructions and medication were given to the patient [Figures 11–13].

Figure 11.

White mineral trioxide aggregate on remaining cavity

Figure 13.

Suture

Figure 12.

Bone graft placement

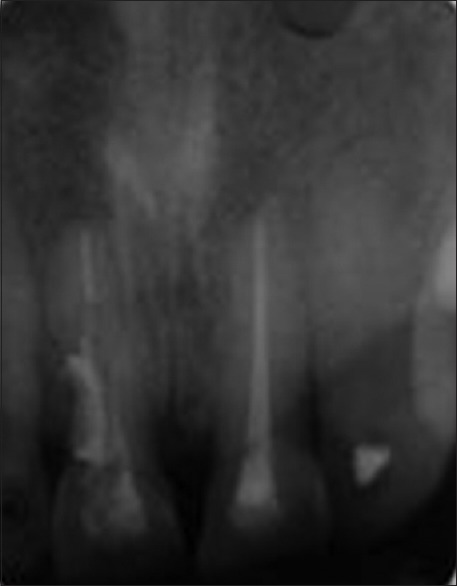

A week later, the sutures were removed. The patient did not report pain or inflammation. Clinical and radiovisiography evaluations were scheduled every 3 and 6 months, respectively [Figure 14]. During the postsurgical months, no communication was found between the gingival sulcus and the coronal aspect of the resorptive cavity.

Figure 14.

Postoperative after 6 months

Discussion

Invasive cervical resorption can be arrested and treated successfully over the long-term.

The failure are:

Structural damage

Recurrence of the resorption

Crown fracture in the cervical area.[9]

It is possible that the tooth been restored with a post in combination with a composite resin material, the restorative treatment might have provided even greater longevity.

Etiology

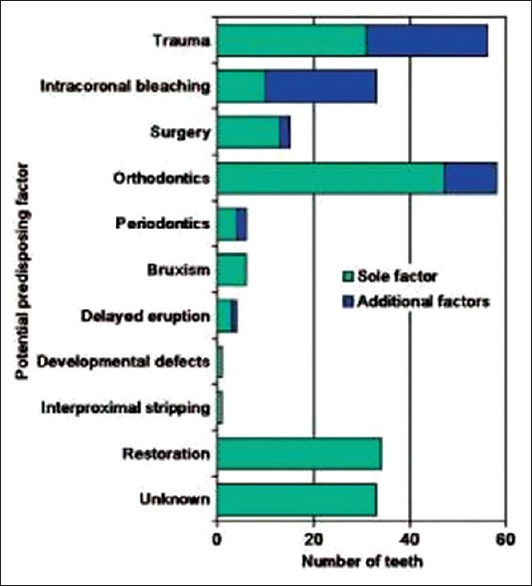

External resorption can be divided into three groups [Figure 15]:[10]

Figure 15.

Predisposing factors

Trauma-induced tooth resorption

Infection-induced tooth resorption

Hyperplastic invasive tooth resorption.

Mechanism of invasive cervical resorption

It is broadly accepted that either damage to or deficiency of the protective layer (gaps) of cementum apical to the gingival epithelial attachment exposes the root surface to osteoclasts, which then resorbs the dentine.[10]

Histology

The resorptive lesions consists of granulomatous tissue

Osteoclasts observed on the resorbing front within the lacunae

The predentin and innermost layer of dentin prevent the ECR lesion from involving the pulp

The resorption expands in a circumferential and apico-coronal direction around the root canal

The outer surface of enamel also resistant to resorption by odontoclastic dissolution of the interprismatic enamel.[2]

Clinical signs

Located in cervical region of tooth

Tooth shows a positive response to vitality test

Pink spot (enamel) might be noted by patient/dentist

Profuse and spontaneous bleeding on probing

Sharp, thinned out edges around the resorptive cavity.[2]

Radiologic signs

Radiolucent area with irregular margins in cervical/proximal region of tooth

Early lesions - radiolucent

Advanced lesions - mottled (fibro-osseous)

Root canal may be visible and intact indicating lesion is external.[2]

Treatment objectives

Arrest resorptive process

Restore damaged root surface

Prevent further resorption

-

Improve esthetics of tooth

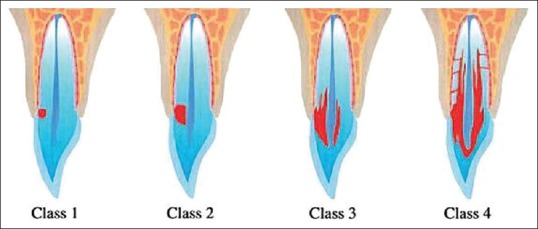

Figure 16.

Heithersay's clinical classification

Topical application of trichloroacetic acid results in coagulation necrosis of the external cervical resorptive tissue, with no damage to adjacent periodontal tissues. Endodontic treatment might be necessary with some class 2 and usually class 3 lesions when there is pulpal involvement.[11]

Recently, cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), has been used to assess ECR lesions, trichloroacetic acid totally eliminates the hydroxyapatite from the dentin surface, so no calcium available for bonding by glass ionomer cement. Therefore, before bonding the surface should be refreshed with a bur to provide a normal dentin surface.[12] When the resorptive defect restoration procedure is preceded by a surgical approach, the materials are frequently placed in close contact with the periodontium. Therefore, it is important to consider that although materials are not sensitive to moisture, blood contamination, biocompatibility, and sealing ability these conditions may induce periodontal regeneration and bony repair during the healing process.[13] Available evidence suggests that MTA is the material of choice in a clinical condition in which the resorptive process never reaches the supragingival area before the surgical approach. As in the present case, MTA favors its full setting and isolates the area from a possible microbial contamination.[14,15]

Conclusion

Early detection is essential for successful management and outcome of ECR. Patients with a history of one or more predisposing factors should be monitored closely for initial signs of ECR. Radiographic/CBCT investigation should be routinely checked for ECR lesions if the teeth in question have been exposed to one or more of the predisposing factors.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Kim Y. Invasive cervical resorption: Treatment challenges, restorative dentistry and endodontics. 2012;37(4):228–31. doi: 10.5395/rde.2012.37.4.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Southam JC. Clinical and histological aspects of peripheral cervical resorption. J Periodontol. 1967;38:534–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.1967.38.6_part1.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gold SI, Hasselgren G. Peripheral inflammatory root resorption: A review of the literature with case reports. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:523–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1992.tb00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frank AL. External-internal progressive resorption and its non-surgical correction. J Endod. 1981;7:473–6. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(81)80310-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frank AL, Blakland LK. Non endodontic therapy for supra osseous extracanal invasive resorption. J Endod. 1987;13:348–55. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(87)80117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trope M. Root resorption due to dental trauma. Endod Topics. 2002;1:79–100. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fish EW. Benign neoplasia of tooth and bone. Proc R Soc Med. 1941;34:427–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel S, Ford TP. Is the resorption external or internal? Dent Update. 2007;34:218–20. doi: 10.12968/denu.2007.34.4.218. 222, 224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel S, Kanagasingam S, Pitt Ford T. External cervical resorption: A review. J Endod. 2009;35:616–25. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stropko JJ. Invasive cervical resorption (ICR): A description, diagnosis and discussion of optional management – A review of four long-term cases. Roots. 2012;4:6–16. CE article. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heithersay GS. Invasive cervical resorption. Endod Topics. 2004;7:73–92. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwartz RS, Robbins JW, Rindler E. Management of invasive cervical resorption: Observations from three private practices and a report of three cases. J Endod. 2010;36:1721–30. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SY, Yang SE. Surgical repair of external inflammatory root resorption with resin-modified glass ionomer cement. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:e33–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernández R, Rincón JG. Surgical endodontic management of an invasive cervical resorption class 4 with mineral trioxide aggregate: A 6-year follow-up. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112:e18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olivieri JG, Duran-Sindreu F, Mercadé M, Pérez N, Roig M. Treatment of a perforating inflammatory external root resorption with mineral trioxide aggregate and histologic examination after extraction. J Endod. 2012;38:1007–11. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]