Abstract

Yersinia pestis, the causative agent of bubonic, pneumonic, and septicaemic plague, remains a major public health threat, with outbreaks of disease occurring in China, Madagascar, and Peru in the last five years. The existence of multidrug resistant Y. pestis and the potential of this bacterium as a bioterrorism agent illustrates the need for new antimicrobials. The β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthases, FabB, FabF, and FabH, catalyse the elongation of fatty acids as part of the type II fatty acid biosynthesis (FASII) system, to synthesise components of lipoproteins, phospholipids, and lipopolysaccharides essential for bacterial growth and survival. As such, these enzymes are promising targets for the development of novel therapeutic agents. We have determined the crystal structures of the Y. pestis β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthases FabF and FabH, and compared these with the unpublished, deposited structure of Y. pestis FabB. Comparison of FabB, FabF, and FabH provides insights into the substrate specificities of these enzymes, and investigation of possible interactions with known β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase inhibitors suggests FabB, FabF and FabH may be targeted simultaneously to prevent synthesis of the fatty acids necessary for growth and survival.

The gram negative bacterium Yersinia pestis, causative agent of bubonic, pneumonic, and septicaemic plague, remains a major public health threat. Responsible for three human pandemics; the Justinian plague (sixth to eighth centuries), the Black Death (fourteenth to nineteenth centuries), and modern plague (nineteenth century to the present day), Y. pestis remains endemic in many parts of North America, South America, south east Asia, and Africa1, with outbreaks occurring in China2, Madagascar3, and Peru4 in the last five years.

As pneumonic plague, Y. pestis is highly contagious and able to spread from human-to-human through respiratory droplets, averting the normal zoonotic route of infection in which plague is spread through contact with infected fleas5,6. Y. pestis can also remain viable in soil for at least 24 days7, and in bottled water for 72–160 days, dependent on the strain8. If left untreated, Y. pestis infections are usually fatal, resulting in death in as little as 24 h after onset of symptoms5,9,10. These characteristics illustrate the potential of Y. pestis as a biological weapon, with the USA Centre for Disease Control and Prevention classifying this bacterium as a Category A bioterrorism threat.

In this context, reports of antimicrobial resistance in Y. pestis are alarming, with evidence of two multiple drug resistant (MDR) strains displaying high level resistance to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, kanamycin, streptomycin, spectinomycin, sulfonamides, tetracycline, and minocycline, agents commonly used for either treatment or prophylaxis11,12. The lethality of untreated infections, the highly contagious nature of pneumonic plague, and the potential of Y. pestis as a biological weapon, combined with the emergence of MDR strains, illustrates that Y. pestis poses a major threat to public health, and the need for new antimicrobial agents to treat drug resistant strains.

The type II fatty acid biosynthesis (FASII) system of bacteria, required by many bacteria for the synthesis of essential lipoproteins, phospholipids, and lipopolysaccharides, is an attractive target for drug discovery. In contrast to the multi-domain mammalian type I fatty acid synthase (FASI) complex, each reaction of the FASII pathway is catalysed by a discrete enzyme (see Zhang, et al.13, Cronan and Thomas14, and Parsons and Rock15 for comprehensive reviews). The β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP) synthases, FabB, FabF, and FabH, catalyse the Claisen condensation of fatty acyl-thioesters and malonyl-ACP to form a β-ketoacyl-ACP intermediate elongated by two carbon atoms. The initial cycle of elongation is catalysed by FabH, involving condensation of malonyl-ACP and acetyl-CoA, while subsequent cycles of elongation are performed by FabB or FabF. Interestingly, whilst FabB and FabF have overlapping substrate specificities, FabB appears necessary in Escherichia coli for elongation of the 10-carbon unsaturated cis-3-decenoyl-ACP intermediate formed by FabA, a crucial role in unsaturated fatty acid synthesis, with E. coli FabF unable to perform this reaction. Conversely, FabF appears necessary for thermal regulation of membrane fluidity, and the elongation of palmitoleate (C16:1) to cis-vaccenate (C18:1). However, FabF enzymes from bacteria that do not possess a FabB homologue are able to fulfil the role of FabB, implying an evolution of these enzymes to incorporate both activities16,17,18.

Despite catalysing different reactions of the FASII pathway, FabB, FabF, and FabH all share a similar active site architecture and reaction mechanism. The active site of all three enzymes consists of a catalytic triad centred around a cysteine residue, with FabB and FabF enzymes both possessing a Cys/His/His catalytic triad19,20, while FabH possesses a Cys/His/Asn catalytic triad21,22. Importantly, these structural similarities may permit the design of new antimicrobials able to target multiple β-ketoacyl-ACP synthases simultaneously, as has been observed with platencin, platensimycin, and thiolactomycin, which have been shown to inhibit the FASII condensing enzymes of E. coli, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and Staphylococcus aureus with varying degrees of success23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. Cerulenin has also been shown to inhibit FabB and FabF enzymes, but is a poor inhibitor of FabH23,29,31,32. An inhibitor targeting all three β-ketoacyl-ACP synthases simultaneously would effectively eliminate synthesis of the fatty acids necessary for growth and survival.

Here we describe the crystal structures of the Yersinia pestis β-ketoacyl-ACP synthases FabF and FabH, and compare these with the unpublished, deposited structure of FabB, presenting three promising targets for the development of new antimicrobials to combat MDR Y. pestis strains.

Materials and Methods

Cloning

The genes encoding YpFabF (accession no. YP_002346612.1) and YpFabH (accession no. YP_002346608.1) were amplified from genomic DNA by PCR using HotStarTaq PCR Master Mix (Qiagen) and cloned into the expression vector pMCSG21, encoding a N-terminal hexahistidine tag with a Tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage site, via ligation-independent cloning as described previously33,34.

Expression and purification

Recombinant YpFabH and YpFabF were expressed as His-tagged fusion proteins in E. coli BL21(DE3) pLysS cells. Briefly, 5 ml Luria-Bertani (LB) broth supplemented with spectinomycin (100 μg ml−1) and chloramphenicol (34 μg ml−1) was inoculated and incubated overnight at 310 K and 220 rev min−1. This culture was used to inoculate auto-induction medium (Studier, 2005) containing spectinomycin (100 μg ml−1) and chloramphenicol (34 μg ml−1), which was incubated overnight at ~298.15 K and 90 rev min−1. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in His buffer A (50 mM phosphate buffer pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole). The His-tagged proteins were purified by affinity chromatography (HisTrap HP column, GE Healthcare), unbound proteins were removed by extensive washing with His buffer A, and recombinant protein was eluted using an increasing concentration gradient of His buffer B (50 mM phosphate buffer pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole). Following elution of protein, fractions containing recombinant YpFabF or YpFabH were incubated with TEV protease (~0.1 mg ml−1) for 14 h at ~277 K to cleave the His-tag. Target proteins were further purified by size-exclusion chromatography (S-200 column, GE Healthcare) and eluted in 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 125 mM NaCl. Fractions containing the purified protein were concentrated using an Amicon ultracentrifugal device (Millipore) with a 10 kDa molecular-weight cut-off. The concentrated proteins were assessed by SDS-PAGE to be >90% pure, and stored at 193.15 K.

Crystallisation

Initial crystallisation screens were performed using a range of commercially available crystal screens (Crystal Screen, Crystal Screen 2, PEG/ION, and PEG/ION 2 from Hampton Research; PACT Premier and Proplex from Molecular Dimensions). Crystal screens were performed in VDX 48-well plates (Hampton Research) via the hanging drop vapour diffusion technique, using 1.5 μl recombinant YpFabH or YpFabF solution combined with 1.5 μl reservoir solution, suspended over 300 μl reservoir solution, and incubated at 296 K.

Feather shaped YpFabH crystals were observed in Hampton Research Crystal Screen condition 41 (10% Propan-2-ol, 0.1 M HEPES sodium salt pH 7.5, 20% PEG4000). YpFabF crystals were obtained in multiple conditions from the Molecular Dimensions PACT premier crystallisation screen (conditions 19, 20, 21, 32, 33, 43). To obtain single diffraction quality crystals, crystallisation conditions were optimised around different molecular weights and concentrations of PEG, and by varying salt and additive concentrations. Diffraction quality YpFabH crystals were formed in 10% Propan-2-ol, 0.1 M HEPES sodium salt pH 7.5, 15% Glycerol, 24% PEG4000, using a protein concentration of 20 mg ml−1. Acetylated-YpFabH crystals were produced by co-crystallisation with acetyl-CoA at a molar ratio of ~5 moles of acetyl-CoA and ~5 moles of malonyl-CoA to one mole of YpFabH, using the above conditions and a protein concentration of 10 mg ml−1. Diffraction quality YpFabF crystals were obtained in 0.2 M lithium chloride, 0.1 M HEPES sodium salt pH 7.0, 24% PEG6000, using a protein concentration of 21 mg ml−1.

Data collection and structure determination

Prior to data collection, YpFabH and YpFabF crystals were cryoprotected in 20% glycerol and flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen at 100 K. Diffraction data were collected at the Australian Synchrotron. Raw data were indexed and integrated using XDS (YpFabH/acetylated YpFabH)35 or iMosflm (YpFabF)36, and scaled in Aimless37 from the CCP4 suite38,39. The structures of YpFabH and YpFabF were solved by molecular replacement using Phaser40 and a monomer of E. coli FabH (PDB:1HN9) and E. coli FabF (PDB:1KAS) as search models for YpFabH and YpFabF respectively. Successive rounds of model building were performed in Coot41 and refined using Phenix42. A summary of the crystallographic and refinement statistics for apo-YpFabH, acetylated YpFabH, and YpFabF are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. YpFabH and YpFabF data and model statistics.

| apo-YpFabH | acetylated-YpFabH | YpFabF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDB ID | 4YLT | 4Z19 | 4R8E |

| Resolution range (Å) | 40.80–2.20 (2.28–2.20) | 49.26–1.80 (1.84–1.80) | 42.55–2.70 (2.83–2.70) |

| Space group | C2221 | C2221 | P1211 |

| Unit cell length (Å) | a = 91.35 b = 120.02 c = 49.30 | a = 91.46 b = 119.88 c = 49.26 | a = 74.67 b = 63.91 c = 89.29 |

| Unit cell angle (°) | α = 90° β = 90° c = 90° | α = 90° β = 90° c = 90° | α = 90° β = 107.14° c = 90° |

| Total observations | 89126 (4038) | 182940 (9341) | 48943 (6683) |

| Unique reflections | 13326 (927) | 25320 (1418) | 20652 (2789) |

| Multiplicity | 6.7 (4.4) | 7.2 (6.6) | 2.4 (2.4) |

| Completeness (%) | 94.5 (70.4) | 99.3 (96.7) | 92.6 (94.7) |

| Mean I/sigma (I) | 17.9 (5.1) | 12.2 (4.9) | 4.1 (2.0) |

| Mean CC (1/2) | 0.998 (0.943) | 0.991 (0.946) | 0.935 (0.457) |

| R-pim | 0.029 (0.149) | 0.046 (0.147) | 0.132 (0.461) |

| R-meas | 0.075 (0.322) | 0.123 (0.383) | 0.213 (0.722) |

| R-merge | 0.070 (0.282) | 0.114 (0.353) | 0.166 (0.550) |

| R-work | 0.172 | 0.148 | 0.199 |

| R-free | 0.221 | 0.179 | 0.245 |

| Number of atoms* | 2469 | 2564 | 6041 |

| RMSD bonds (Å) | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.005 |

| RMSD angles (°) | 0.876 | 0.994 | 0.903 |

| Ramachandran favoured (%) | 97 | 97 | 96 |

| Ramachandran allowed (%) | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

*Note: Not including hydrogen atoms.

Docking simulations, sequence alignments, and protein interface analysis

Docking of platencin, platensimycin, and thiolactomycin to YpFabH was performed using the SwissDock web service (http://www.swissdock.ch/)43. FabH and FabF sequence alignments were generated using the T-Coffee (http://tcoffee.crg.cat/)44,45 and ESPript (http://espript.ibcp.fr/)46 web services. Protein interfaces and monomer-monomer interactions were assessed using the Protein interfaces, surfaces and assemblies’ service (PISA), at the European Bioinformatics Institute (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/prot_int/pistart.html)47.

Results and Discussion

Diffraction data and structure solution

YpFabH and YpFabF were cloned, recombinantly expressed as 6xHis-tagged fusion proteins in E. coli, purified by a two-step purification incorporating affinity and size exclusion chromatography, and crystallised. YpFabH, acetylated-YpFabH, and YpFabF diffraction data were integrated using XDS and iMosflm, and scaled in Aimless to a resolution of 2.20 Å, 1.80 Å, and 2.70 Å respectively.

Apo-YpFabH crystals displayed C2221 symmetry, with the unit cell parameters a = 91.35, b = 120.02, c = 49.30 Å, and were estimated to contain one YpFabH molecule in the asymmetric unit, with a solvent content of 38.5% and a Matthews coefficient of 2.00 Å3 Da−1. Acetylated YpFabH crystals displayed the same symmetry as apo-YpFabH crystals, and similar unit cell dimensions (see Table 1). YpFabF crystals displayed P1211 symmetry, with the unit cell parameters a = 74.67, b = 63.91, c = 89.29 Å, α = 90, β = 107.14, c = 90°. Based on a molecular weight of 45,500 Da, the asymmetric unit was estimated to contain two YpFabF molecules, with a solvent content of 45.09% and a Matthews coefficient of 2.24 Å3 Da−1.

The crystal structures of YpFabH and YpFabF were solved by molecular replacement, using a monomer of E. coli FabH (PDB:1HN9) and E. coli FabF (PDB:1KAS) as the search models respectively. The final structure of apo-YpFabH was refined to an Rwork of 17.2% and Rfree of 22.1%, acetylated YpFabH to an Rwork of 14.8% and Rfree of 17.9%, and YpFabF to an Rwork of 19.9% and Rfree of 24.5%.

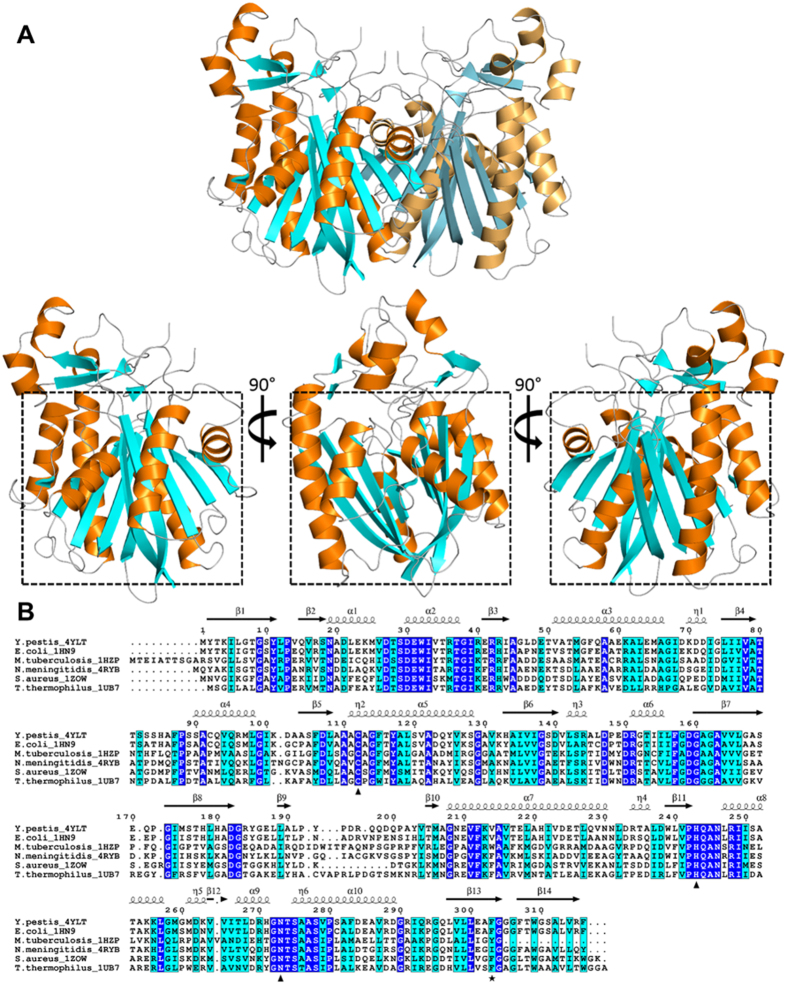

Overall structure of Yersinia pestis FabH

The final model of YpFabH contains a monomer in the asymmetric unit with 10 α-helices and 14 β-strands. The N-terminal and C-terminal halves of YpFabH share a high degree of symmetry, with the two halves arranging to form a thiolase fold motif characteristic of the FASII condensing enzymes19,20,48. The thiolase fold consists of two five stranded mixed β-sheets flanked either side by two α-helices with the topology α-β-α-β-α, in which each α represents two α-helices, and each β represents a five stranded mixed β-sheet (Fig. 1). Based on analysis using PISA, the biological unit of YpFabH is predicted to be a dimer, which is consistent with that observed in bacterial homologues. The dimeric assembly is related by the symmetry operator x,-y,-z, with the two subunits forming a dimer interface burying approximately 15.6% (~1,965 Å2) of the total surface area. The most extensive monomer–monomer interactions are formed between β5 of each subunit which arrange anti-parallel, creating a 10-strand β-sheet that spans the dimer, and a network of hydrogen bonds formed between β5 and α5 (residues 105–130), and the equivalent residues of the opposing monomer, and helix α4, which interacts with β8, β9, and β10 (residues 180–200) of the opposing monomer (Fig. 2A,B).

Figure 1. The structure of Yersinia pestis FabH (YpFabH).

(A) A cartoon representation of YpFabH as a dimer, and a monomer at 0°, 90°, and 180° of rotation around the horizontal axis, with the thiolase fold motif highlighted by a black square. β-sheets are displayed in cyan, α-helices are displayed in orange. (B) Sequence alignment of YpFabH with FabH from E. coli (PDB:1HN9), M. tuberculosis (PDB:1HZP), N. meningitidis (PDB:4QAV), S. aureus (PDB:2GQD), and T. thermophilus (PDB:1J3N). Strictly conserved residues are highlighted in blue with white text, similar residues are highlighted in cyan, residues of the active site catalytic triad are designated by triangles, residue Phe303, which is thought to play a role in substrate specificity, is designated by a black star. Secondary structure features of YpFabH, including α-helices, β-sheets, and 3-10 helices (η) are shown above the sequence alignment in black.

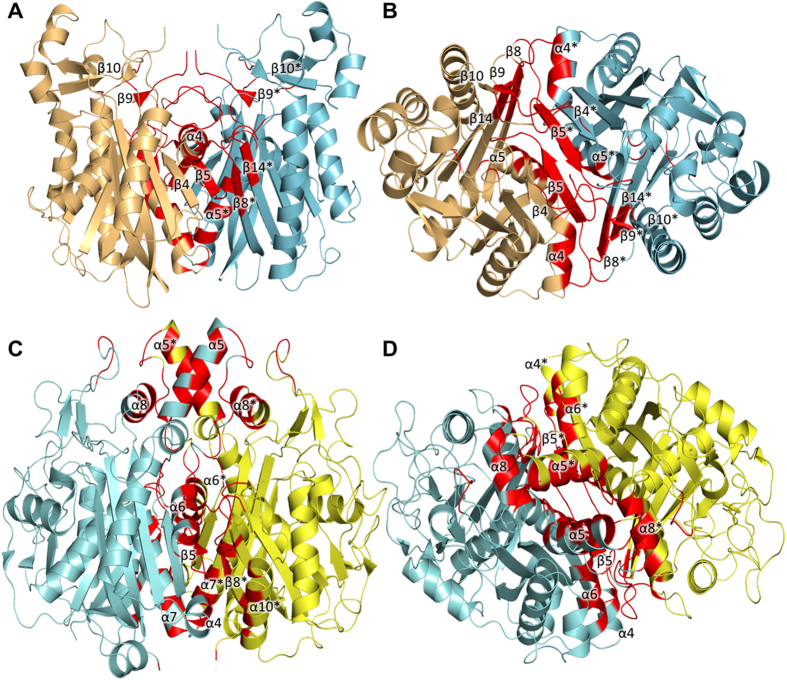

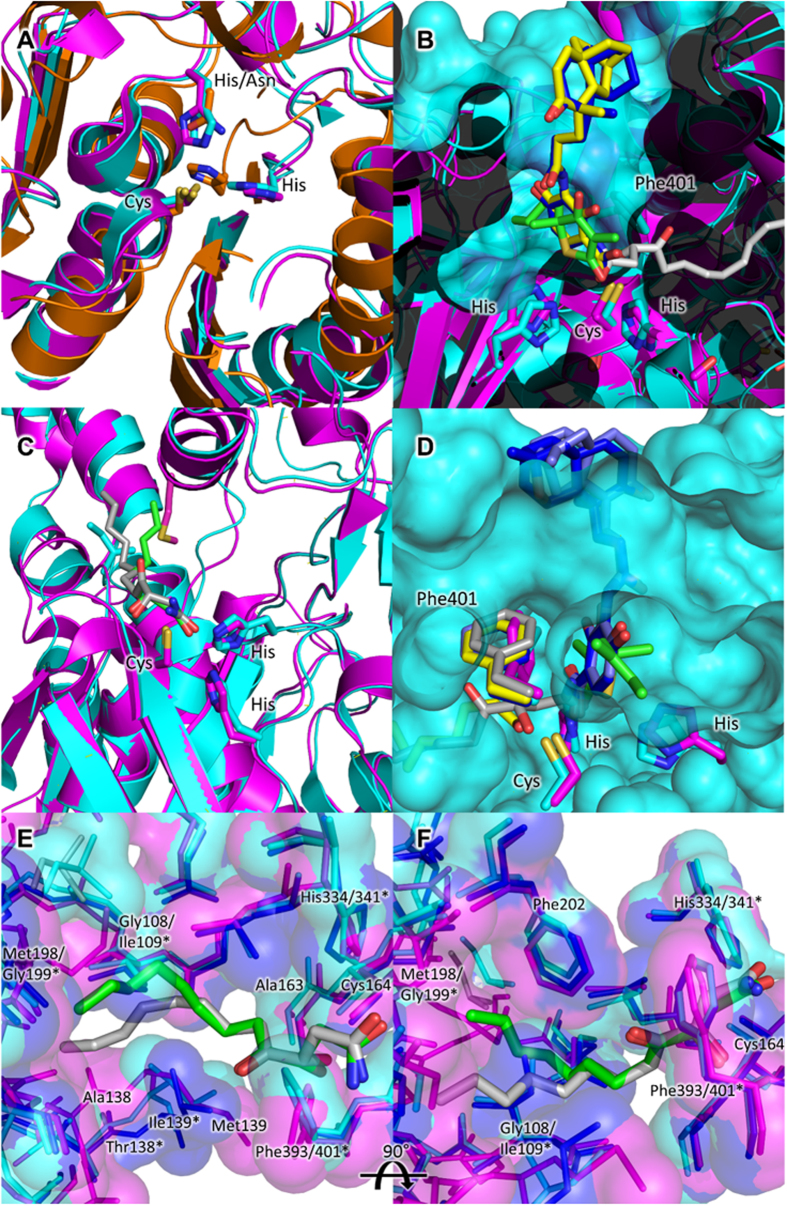

Figure 2. Yersinia pestis FabH (YpFabH) and Yersinia pestis FabF (YpFabH) dimer interfaces.

Secondary structure features of the YpFabH dimer interface at 0° (A) and 90° (B) of rotation around the vertical axis. The most significant interactions of the YpFabH dimer interface occur between β5 and α5, which pack against their counterparts of the opposing monomer forming a 10 stranded β-sheet that spans to two monomers, and α4, which packs against β8, β9, β10, and the adjacent loop regions of the opposing monomer. The YpFabF dimer interface at 0° (C) and 90° (D) of rotation around the vertical axis. The most prominent interactions of the YpFabF dimer interface occur between strand β5, helix α7, and the connecting loops (residues ~160–180) of each monomer, with helix α7 (residues ~170–180) and strand β5 (residues 157–158) interacting with this loop and their counterparts of the opposing monomer. Further interactions are formed between α7 and α10; α4 and α6 that lie against the loop region connecting β8 and α10 of the opposing monomer, and α5 which packs against helices α5 and α8 of the opposing monomer. Interface residues are highlighted in red, opposing monomer secondary structure features are indicated by asterisks (*).

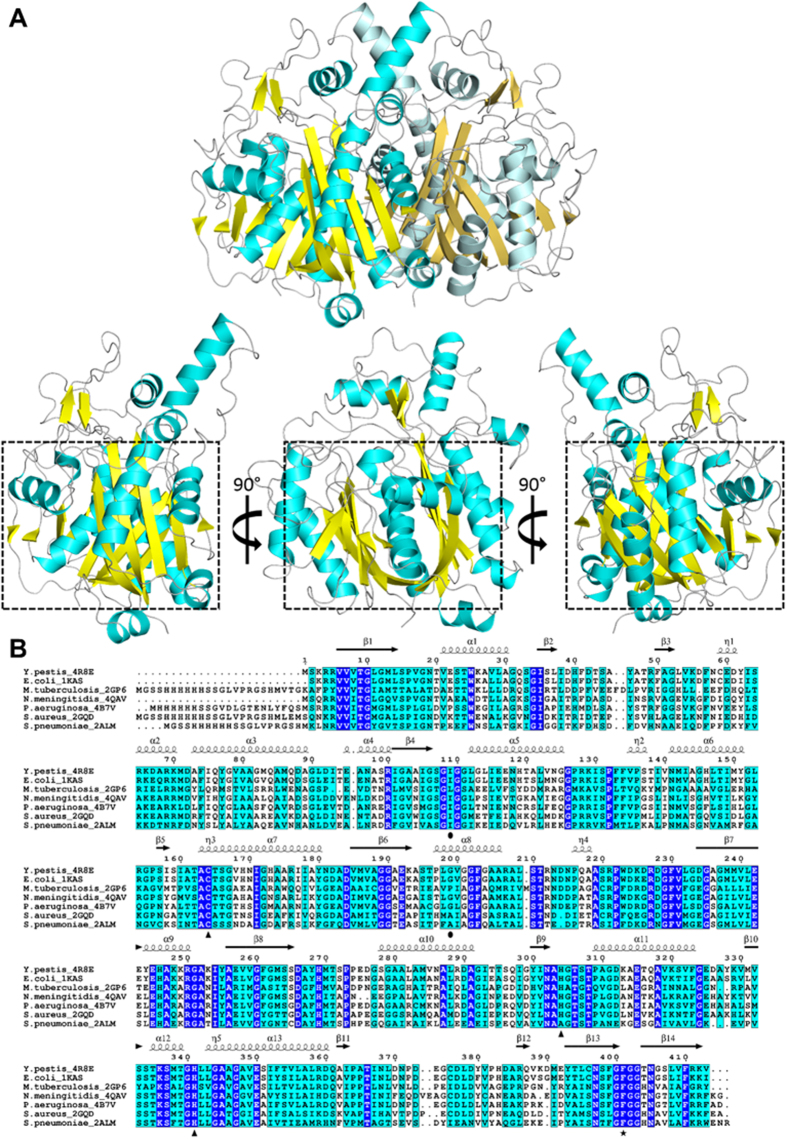

Overall structure of Yersinia pestis FabF

The refined structure of YpFabF contains a dimer within the asymmetric unit, with the YpFabF monomer containing 13 α-helices and 14 β-strands (Fig. 3). Like the YpFabH and YpFabB (PDB: 3OYT, Anderson et al., unpublished) structures, the core motif of YpFabF contains a characteristic thiolase fold, which exhibits the same α-β-α-β-α topology as that observed in YpFabH. Additionally, YpFabF exhibits a similar pattern of dimerisation, with strand β5 of each monomer arranged in an antiparallel fashion, however these β-strands are not positioned to form a contiguous 10-strand β-sheet as observed in YpFabH (Fig. 3). The YpFabF monomers are related by a two-fold crystallographic axis with the most prominent interactions occurring between strand β5, helix α7, and the adjoining loop regions (residues ~160–170) of each monomer, with helix α7 (residues ~170–180) and strand β5 (residues 157–158) interacting with this loop and their counterparts on the opposing monomer. Additional interactions are formed between α7 and α10, α4 and α6 that pack against the loop region connecting β8 and α10, and α5, which packs against helices α5 and α8 of the opposing monomer. In total, this dimer interface buries approximately 18% (~2,890 Å2) of the solvent accessible surface area (Fig. 2C,D).

Figure 3. The structure of Yersinia pestis FabF (YpFabF).

(A) A cartoon representation of YpFabF as a dimer, and a monomer at 0°, 90°, and 180° of rotation around the horizontal axis, with the thiolase fold motif highlighted by a black square. β-sheets are displayed in yellow, α-helices are displayed in cyan. (B) Sequence alignment of YpFabF with FabF from E. coli (PDB:2GDW), M. tuberculosis (PDB:2GP6), N. meningitidis (PDB:4QAV), S. pneumoniae (PDB:2ALM), S. aureus (PDB:2GQD), and T. thermophilus (PDB:1J3N). Strictly conserved residues are highlighted in blue with white text, similar residues are highlighted in cyan, residues of the active site catalytic triad are designated by triangles, residues Ile109 and Gly199, which are thought to direct the fatty acyl substrate, are designated by black circles, the gatekeeper residue Phe401 is designated by a black star. Secondary structure features of YpFabF, including α-helices, β-sheets, and 3-10 helices (η) are shown above the sequence alignment in black.

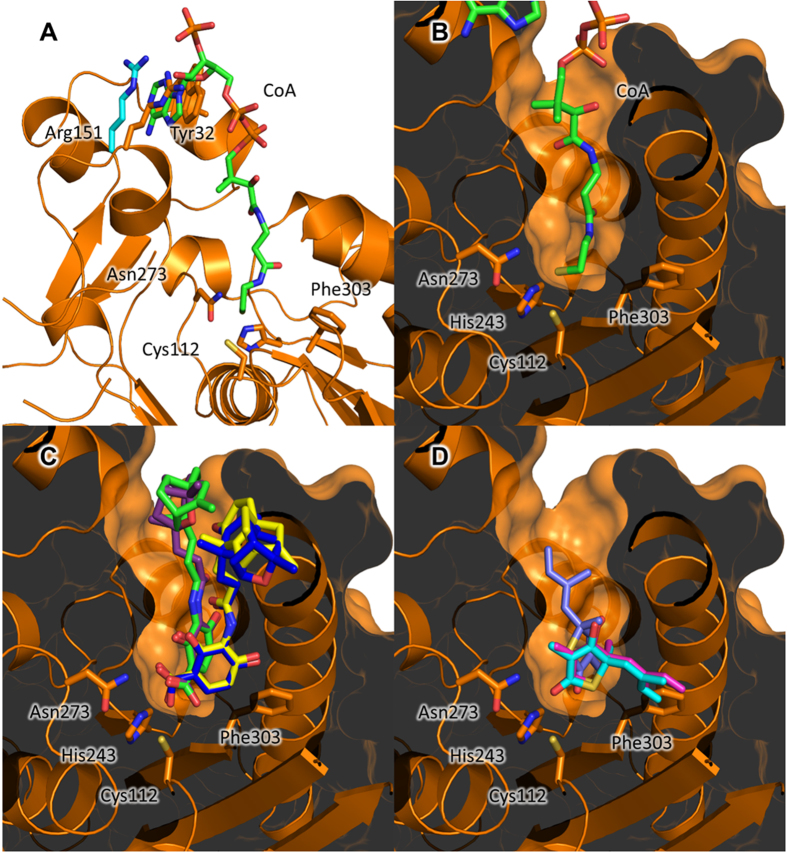

Active site architecture of Yersinia pestis FabH and FabF

Both the active sites and reaction mechanisms of the FASII condensing enzymes have been well characterised, with FabB and FabF enzymes possessing a Cys/His/His catalytic triad, and FabH enzymes possessing a Cys/His/Asn catalytic triad. Based on structural homology with related Fab enzymes, reaction mechanisms of YpFabH and YpFabF are likely to follow a two-stage mechanism. Driven by a dipole moment, the active site cysteine, Cys112 and Cys164 in YpFabH (Fig. 4) and YpFabF (Fig. 5) respectively, attacks the acyl group of a fatty acyl donor, transferring the acyl group to the enzyme. The bound fatty acyl donor molecule is displaced, and the receiving molecule or fatty acyl thioester to be elongated binds, initiating the transfer of the acyl group from the condensing enzyme to the recipient. The remaining residues of the catalytic triad, His243 and Asn273 of YpFabH (Fig. 4), and His304 and His341 of YpFabF (Fig. 5), are thought to stabilise the fatty acyl intermediate during transition states20,22,49.

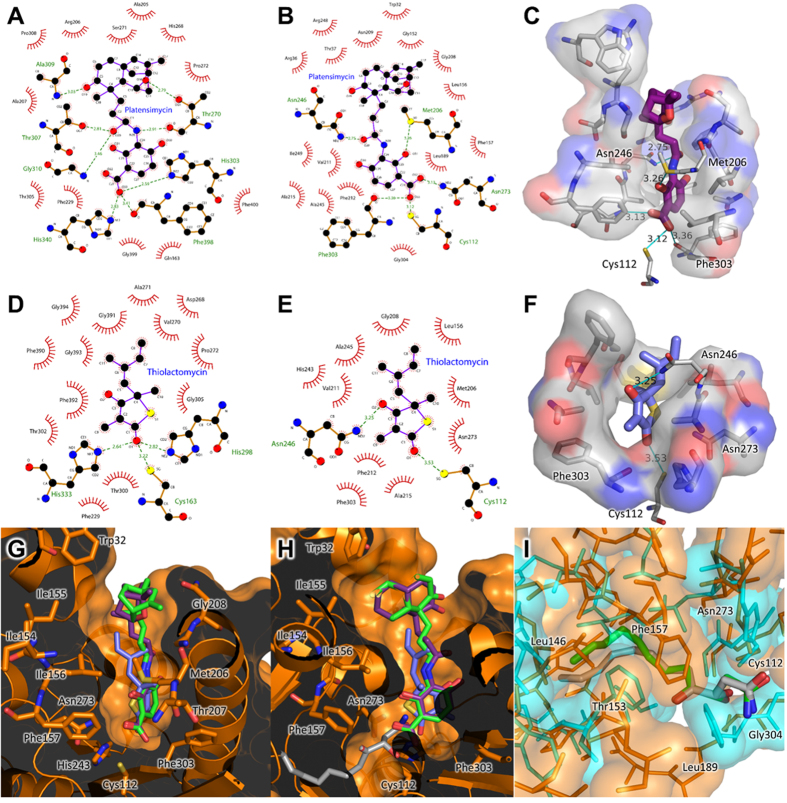

Figure 4. Possible substrate and inhibitor interactions of Yersinia pestis FabH (YpFabH).

(A) Superposition of CoA (green) from E. coli FabH (PDB:1HND) onto YpFabH. Arg151 of YpFabH clashes with the adenine ring of CoA and likely adopts a conformation similar to that observed in E. coli (cyan) to accommodate the substrate. (B) Superposition of CoA (green) also shows the phosphopantetheine arm of CoA extending the length of the binding pocket of YpFabH to reach the active site cysteine. (C) Docking of platencin (green) and platensimycin (purple) to YpFabH suggests a highly similar binding site to that observed in FabF homologues (PDB:3HO2, yellow; PDB:3HNZ, blue). (D) Superposition of thiolactomycin bound to FabB (PDB:1FJ4, magenta) and a Mycobacterium homologue (PDB:2WGE, cyan) shows the inhibitor conformation is incompatible with the YpFabH binding pocket. Docking of thiolactomycin (light blue) to YpFabH indicates the inhibitor rotates approximately 90°, with the cyclic motif maintaining a similar location within the active site.

Figure 5. The active sites of Yersinia pestis β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthases and potential interactions with known inhibitors of the FASII condensing enzymes.

(A) Superposition of the putative YpFabH (orange), YpFabF (cyan), and YpFabB (magenta) active sites. (B) Superposition of cerulenin (PDB:1B3N, silver), platencin (PDB:3HO2, yellow), platensimycin (PDB:3HNZ, blue), and thiolactomycin (PDB:1FJ4, green) from bacterial FabF/FabB homologues into the active sites of YpFabB (magenta) and YpFabF (cyan) reveals no steric clashes or modifications which would prevent inhibition, with the exception of Phe401, which is thought to rotate into an open conformation upon substrate or inhibitor binding. (C) Superposition of cerulenin bound E. coli FabB (PDB:1FJ8, silver) and FabF (PDB:1B3N, green) showing the differing conformations of the acyl chain, and residues Ile108 of FabF (cyan) and Met198 of FabB (magenta), which direct the acyl chain of the inhibitor (cyan residue is acting upon green inhibitor, magenta residue is acting upon silver inhibitor) and possibly fatty acyl substrates. (D) A view from the interior of YpFabF, showing access to part of the substrate binding pocket of YpFabF (cyan) is closed off by Phe401. The conformation of Phe401 in FabF/FabB structures bound to cerulenin (PDB:1FJ8, silver), platencin (PDB:3HO2, light blue), platensimycin (PDB 3HNZ, blue), and thiolactomycin (PDB:1FJ4, green) closely mimic that of FabF in complex with lauroyl-CoA (PDB:2GFY, yellow). Superposition of YpFabB (magenta), YpFabF (cyan) and N. meningitidis FabF (PDB:4QAV, dark blue) active sites, and cerulenin from cerulenin bound E. coli FabB (PDB:1FJ8, silver) and FabF (PDB:1B3N, green) structures at 0° (E) and 90° (F) rotation around the vertical axis. Both the residues and surface of the YpFabB and YpFabF active sites and substrate binding pockets are highly similar. The only significant differences appear to be the replacement of Ile109 and Gly199 (Ile108 and Gly199 in E. coli) of FabF, with Gly108 and Met198 of FabB (magenta), and residues 138–140 of both enzymes, with no obvious differences between YpFabF and FabF from N. meningitidis, which does not possess a FabB homologue. YpFabF residues indicated by asterisks (*), YpFabB and residues common to both YpFabB and YpFabF are not marked.

The order of substrate binding and thus reaction order in FabF and FabB is thought to be controlled by residue Phe401 (YpFabF numbering) which acts as a “gatekeeper”, rotating upon acylation of the active site cysteine to expand the substrate binding pocket and allow the fatty acyl thioester, malonyl-ACP, to be elongated (Fig. 5D)20,49. While both FabB and FabF possess a similar active site phenylalanine “gatekeeper” residue, the structural elements that give rise to the differing substrate specificities of FabB and FabF are not known. Based on inspection of E. coli FabB and FabF structures in complex with cerulenin, Price, et al.23 suggest Gly107 and Met197 of E. coli FabB (Gly108 and Met198 of YpFabB) direct the tail of the acyl chain toward strand β4, while the equivalent residues in E. coli FabF, Ile108, and Gly198 (Ile109 and Gly199 of YpFabF), direct the tail of the acyl chain away from β4. As such, Gly107/Ile108 and Met198/Gly199 are thought to induce a binding pocket conformation suited to the kinked structure of the unsaturated cis-3-decenoyl-ACP intermediate elongated by FabB (Fig. 5C,E,F). Residues Gly107/Ile108 and Met198/Gly199 are conserved in YpFabB and YpFabF, however Ile108 is also conserved in the FabF enzymes of Neisseria meningitidis, S. aureus, and Streptococcus pneumoniae, which do not possess FabB homologues and rely on FabF as the sole elongating enzyme. Gly199 is also conserved in N. meningitidis, while this residue is replaced by alanine in S. aureus and S. pneumoniae. That Ile108 and Gly198 are conserved or replaced by a similar residue in FabF enzymes, which supplant the role of FabB, indicates that residues Gly107/Ile108 or Met198/Gly199 do not solely account for the inability of E. coli FabF to elongate unsaturated cis double bond containing intermediates produced by FabA.

The molecular basis for FabH substrate specificity has been suggested to stem from differing rotamer conformations within the substrate binding pocket. Gajiwala, et al.50 propose that different rotamer conformations, rather than amino acid substitutions or inserts observed within the binding pocket of FabH enzymes, account for differing FabH substrate specificities, with enzymes that utilise branched chain fatty acids adopting a conserved rotamer conformation equivalent to that of Phe298 in S. aureus FabH, Phe312 in Enterococcus faecalis FabH, and Tyr304 in M. tuberculosis FabH (Fig. 1B), where the aromatic ring of Phe/Tyr is rotated inward towards the active site, causing a reduction in the size of the hydrophobic pocket. The rotation of the equivalent residue in YpFabH (Phe303) is turned away from the active site mimicking that of E. coli, which would suggest a similar substrate specificity to that of E. coli FabH. However, the relevance of the role of this rotamer conformation in YpFabH substrate specificity, if any, has not yet been determined.

To further characterise the active site and substrate interactions of YpFabH, we attempted to co-crystallise YpFabH with acetyl-CoA. Unlike the apo-YpFabH structure, the active site cysteine (Cys112) of this complex is acetylated, with no CoA phosphopantetheine moiety visible within the structure. Based on comparison with structures of E. coli FabH in complex with CoA (PDB:1HND, 1HNH), the absence of CoA in our acetylated-YpFabH structure appears to be due to crystal packing, with crystal contacts overlapping with the 3′-ribose phosphate and ribose moiety of CoA, indicating the first stage of the reaction has taken place and the CoA molecule has been displaced from the binding pocket in anticipation of the fatty acyl recipient prior to crystallisation. Despite the acetylation of the active site cysteine, the active site appears largely unchanged, with no obvious conformational changes observed, and as the CoA phosphopantetheine moiety is absent, the interactions between this enzyme and substrate cannot be determined. However, superposition of CoA bound E. coli FabH structures (PDB:1HND, 1HNH) onto the structure of YpFabH (Fig. 4A,B) indicates the phosphopantetheine moiety of CoA is stabilised by hydrogen bonds with Arg36, Asn209, and Asn246, while the adenine moiety appears to form a hydrogen bond with Thr28 and aromatic stacking interactions with Trp32. Superposition of these models also suggests Arg151, which clashes with the adenine moiety of CoA, moves to accommodate the substrate, with the adenine ring stacked between Trp32 and Arg151 in a planar fashion (Fig. 4A,B).

Potential inhibitor interactions of cerulenin, platencin, platensimycin, and thiolactomycin, with Yersinia pestis FabB, FabF, and FabH

Despite a relatively low sequence identity (~30–40%), the overall structures of YpFabB, YpFabF, and YpFabH are highly similar (Fig. 5A,B), with an RMSD of ~2.3 Å over ~240 residues between YpFabB and YpFabF, and YpFabH, and an RMSD of 1.24 Å over 388 residues between YpFabB and YpFabF. The structural similarity of these enzymes extends to their active sites, with the inhibitors cerulenin, platencin, platensimycin, and thiolactomycin shown to inhibit multiple FASII condensing enzymes23,24,25. Docking of platencin, platensimycin, and thiolactomycin to apo-YpFabH (Fig. 4C,D) reveals similar conformations to those observed in the crystal structures of E. coli FabF bound to these inhibitors (Fig. 5B), however thiolactomycin appears to rotate to avoid steric clashes with residues of the active site. Cerulenin, platencin, platensimycin, and thiolactomycin are all thought to mimic the fatty acyl thioester substrate of the FASII condensing enzymes. This is somewhat evident by the rotation of the FabF/FabB “gatekeeper” residue Phe401 in inhibitor bound complexes to a conformation equivalent to that observed in the structure of E. coli FabF bound to lauroyl-CoA (Fig. 5D).

Whilst platencin, platensimycin, and thiolactomycin all inhibit FabH, both platensimycin and thiolactomycin inhibit FabH poorly (IC50 values of 67 μM and ~100 μM respectively), and cerulenin exhibits little to no inhibition of FabH. Platencin exhibits ~4 fold greater inhibitory activity (IC50 = 16.2 μM) compared with platensimycin23,24,25,51, with docking of platencin and platensimycin into the active site of YpFabF and YpFabH showing that the terminal carboxylic acids of platencin and platensimycin form hydrogen bonds with residues His243 and Asn273 of YpFabH, and His304 and His341 of YpFabF. This is consistent with E. coli FabH docking studies performed by Jayasuriya, et al.52, who suggest the difference in inhibitory activity between platencin and platensimycin stems from interactions between FabH and the ketolide motifs of these inhibitors. The nonpolar residues Ile155, Ile156, and Trp32, posed at the entrance to the binding site of E. coli FabH, surround the polar ether oxygen atom of the pentacyclic ketolide motif of platensimycin. In YpFabH, a similar environment is formed by residues Ile154, Ile155, Leu156, and Trp32. The ether oxygen of platensimycin in our docked models lies near the non-polar residues Met206 and Gly208 (Fig. 6), however both the conformations presented here and those proposed by Jayasuriya, et al.52 suggest unfavourable interactions. In contrast to platensimycin, the tetracyclic ketolide of platencin lacks the polar oxygen atom, allowing platencin to form favourable hydrophobic interactions with residues Trp32, Ile154, Ile155, and Leu156, or Met206, Ala207, and Gly208 (Fig. 6G,H).

Figure 6. Comparison of interactions between known inhibitors of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthases and Yersinia pestis FabH docked models.

2D representations of the interactions between platensimycin and E. coli FabF (A), and that of platensimycin docked to YpFabH (B), indicate substantially fewer bonds are formed between platensimycin and YpFabH compared to that of E. coli FabF (PDB:2GFX), and the non-polar residues Met206 and Gly208, which may repel the ether oxygen in the ketolide moiety of platensimycin. Hydrogen bonds are represented by green dashed lines, hydrophobic contacts are shown as red circular arcs. (C) A 3D diagram of the interactions between platensimycin and YpFabH identified in Fig. 6B, showing potential hydrogen bonds (blue lines) and hydrophobic interactions (silver clouds). 2D representations of the interactions between thiolactomycin and E. coli FabB (PDB:1FJ4) (D), and that of thiolactomycin docked to YpFabH (E), suggests the rotation of thiolactomycin to fit into the YpFabH binding pocket, and the loss of dual histidine residues in the catalytic triad reduces the number of bonds which would stabilise thiolactomycin when bound to YpFabH, compared to E. coli FabB/FabF. (F) A 3D diagram of the interactions between thiolactomycin and YpFabH identified in Fig. 6E, showing potential hydrogen bonds (blue lines) and hydrophobic interactions (silver clouds). (G) A cut-away view of the YpFabH (orange) active site surface showing residues that may interact with platencin (green), platensimycin (purple), and thiolactomycin (light blue). (H) Superposition of cerulenin (PDB:1FJ8, silver) into the active site of YpFabH suggests the active site is too small to accommodate the inhibitor, which may partially account for the poor inhibition of FabH exhibited by cerulenin. (I) Superposition of YpFabH (orange), YpFabF (cyan), and cerulenin from cerulenin bound E. coli FabB (PDB:1FJ8, silver) and FabF (PDB:1B3N, green) structures suggests that the YpFabH substrate binding pocket is shorter than that of YpFabF, at least partly due to hydrophobic residues that lie near the catalytic triad, thus any future drug design efforts should accommodate for the differences in depth between the substrate binding pockets of FabB, FabF and FabH 2D representations were generated using LigPlot+55.

The weak inhibitory activity of thiolactomycin and cerulenin against FabH, compared to that against FabF and FabB, is believed to stem from differences in the catalytic triad of these enzymes, with mutation of the Cys/His/His triad of E. coli FabB to a Cys/His/Asn triad similar to that observed in FabH shown to reduce the sensitivity of FabB to cerulenin by 10 fold and thiolactomycin by 14 fold23. Furthermore, the rotation of thiolactomycin to avoid steric clashes with the FabH active site, as evident in our docked model, may reduce the number of residues able to bind the inhibitor (Fig. 6D,F). Additionally, the substrate binding pockets of E. coli and S. aureus FabH enzymes are too short to accommodate the acyl chain of cerulenin, resulting in unfavourable steric clashes23,29 (Fig. 6H,I).

While cerulenin, platencin, platensimycin, and thiolactomycin have been shown to inhibit the FASII condensing enzymes, these molecules are not necessarily well suited for use as antimicrobials, with cerulenin, platensimycin, and thiolactomycin analogues also shown to inhibit the mammalian fatty acid synthase complex23,53,54. However, the use of these molecules as lead compounds for structure based drug design has the potential to yield new antimicrobials to combat MDR Y. pestis.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Nanson, J. D. et al. Structural Characterisation of the Beta-Ketoacyl-Acyl Carrier Protein Synthases, FabF and FabH, of Yersinia pestis. Sci. Rep. 5, 14797; doi: 10.1038/srep14797 (2015).

Acknowledgments

We thank the beamline scientists and staff of the Australian Synchrotron for their assistance. We thank Gayle Petersen for proofreading of the manuscript. J.K.F. is an ARC (Australian Research Council) Future Fellow. This manuscript was prepared with funding from the Charles Sturt University Writing Up Award.

Footnotes

Author Contributions J.D.N. and J.K.F. conceived the experiments. J.D.N., C.M.D.S., and Z.H. conducted the experiments. J.D.N. and J.K.F. analysed the results and prepared the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Stenseth N. C. et al. Plague: Past, Present, and Future. PLoS Med 5, e3, 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050003 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge P. et al. Primary case of human pneumonic plague occurring in a Himalayan marmot natural focus area Gansu Province, China. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 33, 67–70, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2014.12.044 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard V. et al. Pneumonic Plague Outbreak, Northern Madagascar, 2011. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 21, 8–15, 10.3201/eid2101.131828 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres O. et al. Whole-Genome Sequencing and Comparative Analysis of Yersinia pestis, the Causative Agent of a Plague Outbreak in Northern Peru. Genome Announc. 1, e00249–00212, 10.1128/genomeA.00249-12 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kool J. L. & Weinstein R. A. Risk of Person-to-Person Transmission of Pneumonic Plague. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40, 1166–1172, 10.1086/428617 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry R. D. & Fetherston J. D. Yersinia pestis–etiologic agent of plague. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10, 35–66 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebecca J. E. et al. Persistence of Yersinia pestis in Soil Under Natural Conditions. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14, 941, 10.3201/eid1406.080029 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torosian S. D., Regan P. M., Taylor M. A. & Margolin A. Detection of Yersinia pestis over time in seeded bottled water samples by cultivation on heart infusion agar. Can. J. Microbiol. 55, 1125–1129, 10.1139/W09-061 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begier E. M. et al. Pneumonic Plague Cluster, Uganda, 2004. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12, 460–467, 10.3201/eid1203.051051 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertherat E. et al. Lessons Learned about Pneumonic Plague Diagnosis from 2 Outbreaks, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17, 778–784, 10.3201/eid1705.100029 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galimand M. et al. Multidrug Resistance in Yersinia pestis Mediated by a Transferable Plasmid. N. Engl. J. Med. 337, 677–681, 10.1056/NEJM199709043371004 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiyoule A. et al. Transferable plasmid-mediated resistance to streptomycin in a clinical isolate of Yersinia pestis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7, 43–48, 10.3201/eid0701.700043 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.-M., White S. W. & Rock C. O. Inhibiting Bacterial Fatty Acid Synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 17541–17544, 10.1074/jbc.R600004200 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronan J. E. & Thomas J. Bacterial Fatty Acid Synthesis and its Relationships with Polyketide Synthetic Pathways. Methods Enzymol. 459, 395–433, 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)04617-5 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons J. B. & Rock C. O. Bacterial lipids: Metabolism and membrane homeostasis. Prog. Lipid Res. 52, 249–276, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.plipres.2013.02.002 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan-Kiss R. M. & Cronan J. E. The Lactococcus lactis FabF Fatty Acid Synthetic Enzyme Can Functionally Replace both the FabB and FabF proteins of Escherichia coli and the FabH protein of Lactococcus lactis. Arch. Microbiol. 190, 427, 10.1007/s00203-008-0390-6 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath R. J. & Rock C. O. Roles of the FabA and FabZ β-Hydroxyacyl-Acyl Carrier Protein Dehydratases in Escherichia coli Fatty Acid Biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 27795–27801, 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27795 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards P., Sabo Nelsen J., Metz J. G. & Dehesh K. Cloning of the fabF gene in an expression vector and in vitro characterization of recombinant fabF and fabB encoded enzymes from Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 402, 62–66, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0014-5793(96)01437-8 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W. et al. Crystal structure of β‐ketoacyl‐acyl carrier protein synthase II from E. coli reveals the molecular architecture of condensing enzymes. EMBO J. 17, 1183–1191 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen J. G. et al. The X-ray crystal structure of β-ketoacyl [acyl carrier protein] synthase I. FEBS Lett. 460, 46–52 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu X. et al. Crystal Structure of β-Ketoacyl-Acyl Carrier Protein Synthase III: A Key Condensing Enzyme in Bacterial Fatty Acid Biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 36465–36471, 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36465 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies C., Heath R. J., White S. W. & Rock C. O. The 1.8 Å crystal structure and active-site architecture of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III (FabH) from Escherichia coli. Structure 8, 185–195 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price A. C. et al. Inhibition of β-Ketoacyl-Acyl Carrier Protein Synthases by Thiolactomycin and Cerulenin: STRUCTURE AND MECHANISM. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 6551–6559, 10.1074/jbc.M007101200 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. et al. Platensimycin is a selective FabF inhibitor with potent antibiotic properties. Nature 441, 358–361, (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. et al. Discovery of platencin, a dual FabF and FabH inhibitor with in vivo antibiotic properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 7612–7616, 10.1073/pnas.0700746104 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustafa G. A. I. et al. Potent growth inhibitory activity of (+/−)-platencin towards multi-drug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Med. Chem. Commun. 4, 720–723, 10.1039/C3MD00016H (2013). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A. K., Taylor R. C., Bhatt A., Fütterer K. & Besra G. S. Platensimycin Activity against Mycobacterial β-Ketoacyl-ACP Synthases. PLoS ONE 4, e6306, 10.1371/journal.pone.0006306 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer L. et al. Thiolactomycin and Related Analogues as Novel Anti-mycobacterial Agents Targeting KasA and KasB Condensing Enzymes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 16857–16864, 10.1074/jbc.M000569200 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X. & Reynolds K. A. Purification, Characterization, and Identification of Novel Inhibitors of the β-Ketoacyl-Acyl Carrier Protein Synthase III (FabH) from Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46, 1310–1318, 10.1128/AAC.46.5.1310-1318.2002 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim P. et al. Structure-activity relationships at the 5-position of thiolactomycin: an intact (5R)-isoprene unit is required for activity against the condensing enzymes from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Escherichia coli. J. Med. Chem. 49, 159–171, 10.1021/jm050825p (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandekar S. S. et al. Identification, Substrate Specificity, and Inhibition of the Streptococcus pneumoniae β-Ketoacyl-Acyl Carrier Protein Synthase III (FabH). J. Biol. Chem. 276, 30024–30030, 10.1074/jbc.M101769200 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K.-H., Kremer L., Besra G. S. & Rock C. O. Identification and Substrate Specificity of β-Ketoacyl (Acyl Carrier Protein) Synthase III (mtFabH) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 28201–28207 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanson J. D. & Forwood J. K. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of FabG from Yersinia pestis. Acta Crystallogr., Sect F: Struct. Biol. Commun. 70, 101–104, 10.1107/S2053230X13033402 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschenfeldt W. H., Stols L., Millard C. S., Joachimiak A. & Donnelly M. I. A Family of LIC Vectors for High-Throughput Cloning and Purification of Proteins. Methods Mol. Biol. 498, 105–115, 10.1007/978-1-59745-196-3_7 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr., Sect D: Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 125–132, 10.1107/S0907444909047337 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battye T. G., Kontogiannis L., Johnson O., Powell H. R. & Leslie A. G. iMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta Crystallogr., Sect D: Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 271–281, 10.1107/S0907444910048675 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans P. R. & Murshudov G. N. How good are my data and what is the resolution? Acta Crystallogr., Sect D: Biol. Crystallogr. 69, 1204–1214, 10.1107/S0907444913000061 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potterton L. et al. Developments in the CCP4 molecular-graphics project. Acta Crystallogr., Sect D: Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2288–2294, 10.1107/S0907444904023716 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn M. D. et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr., Sect D: Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 235–242, 10.1107/S0907444910045749 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy A. J. et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674, 10.1107/S0021889807021206 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G. & Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr., Sect D: Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501, 10.1107/S0907444910007493 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr., Sect D: Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221, 10.1107/S0907444909052925 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosdidier A., Zoete V. & Michielin O. SwissDock, a protein-small molecule docking web service based on EADock DSS. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, W270–277, 10.1093/nar/gkr366 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Tommaso P. et al. T-Coffee: a web server for the multiple sequence alignment of protein and RNA sequences using structural information and homology extension. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, W13–W17, 10.1093/nar/gkr245 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armougom F. et al. Expresso: automatic incorporation of structural information in multiple sequence alignments using 3D-Coffee. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W604–W608, 10.1093/nar/gkl092 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert X. & Gouet P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W320–324, 10.1093/nar/gku316 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krissinel E. & Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797, 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu X. et al. Crystal structure of beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III. A key condensing enzyme in bacterial fatty acid biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 36465–36471 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.-M., Hurlbert J., White S. W. & Rock C. O. Roles of the Active Site Water, Histidine 303, and Phenylalanine 396 in the Catalytic Mechanism of the Elongation Condensing Enzyme of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 17390–17399, 10.1074/jbc.M513199200 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajiwala K. S. et al. Crystal structures of bacterial FabH suggest a molecular basis for the substrate specificity of the enzyme. FEBS Lett. 583, 2939–2946, 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.08.001 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu X. et al. Crystal structure and substrate specificity of the β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III (FabH) from Staphylococcus aureus. Protein Sci. 14, 2087–2094, 10.1110/ps.051501605 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayasuriya H. et al. Isolation and Structure of Platencin: A FabH and FabF Dual Inhibitor with Potent Broad-Spectrum Antibiotic Activity. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 46, 4684–4688, 10.1002/anie.200701058 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden J. M. et al. Application of a Flexible Synthesis of (5R)-Thiolactomycin To Develop New Inhibitors of Type I Fatty Acid Synthase. J. Med. Chem. 48, 946–961, 10.1021/jm049389h (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M. et al. Antidiabetic and antisteatotic effects of the selective fatty acid synthase (FAS) inhibitor platensimycin in mouse models of diabetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 5378–5383, 10.1073/pnas.1002588108 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R. A. et al. LigPlot+: multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J Chem Inf Model. 51(10), 2778–86, 10.1021/ci200227u (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]