Abstract

Previously, we reported sexually dimorphic bone mass and body composition phenotypes in Igfbp2−/− mice (−/−), where male mice exhibited decreased bone and increased fat mass, whereas female mice displayed increased bone but no changes in fat mass. To investigate the interaction between IGF-binding protein (IGFBP)-2 and estrogen, we subjected Igfbp2 −/− and +/+ female mice to ovariectomy (OVX) or sham surgery at 8 weeks of age. At 20 weeks of age, mice underwent metabolic cage analysis and insulin tolerance tests before killing. At harvest, femurs were collected for microcomputed tomography, serum for protein levels, brown adipose tissue (BAT) and inguinal white adipose tissue (IWAT) adipose depots for histology, gene expression, and mitochondrial respiration analysis of whole tissue. In +/+ mice, serum IGFBP-2 dropped 30% with OVX. In the absence of IGFBP-2, OVX had no effect on preformed BAT; however, there was significant “browning” of the IWAT depot coinciding with less weight gain, increased insulin sensitivity, lower intraabdominal fat, and increased bone loss due to higher resorption and lower formation. Likewise, after OVX, energy expenditure, physical activity and BAT mitochondrial respiration were decreased less in the OVX−/− compared with OVX+/+. Mitochondrial respiration of IWAT was reduced in OVX+/+ yet remained unchanged in OVX−/− mice. These changes were associated with significant increases in Fgf21 and Foxc2 expression, 2 proteins known for their insulin sensitizing and browning of WAT effects. We conclude that estrogen deficiency has a profound effect on body and bone composition in the absence of IGFBP-2 and may be related to changes in fibroblast growth factor 21.

IGF-binding protein (IGFBP)-2 is a member of a family of 6 proteins that bind to IGF-1 and IGF-2 with high affinity. These proteins can function to enhance or inhibit IGF actions depending on a number of factors including, but not limited to, the local concentrations of the IGFBPs, IGFs, and IGFBP proteases, as well as the target tissue. In addition to their roles in IGF signaling, a number of IGFBPs have IGF-independent effects (1–3). The role of IGFBP-2 in bone homeostasis is somewhat conflicted with evidence to support agonistic and antagonistic actions depending on the model, the cell autonomous vs cell nonautonomous actions of IGFBP-2, and the age of mice under investigation. Indeed, initial reports suggested an inhibitory effect of IGFBP-2 on bone size and growth in transgenic models (4–6). However, anabolic effects of IGFBP-2 in combination with IGF-2 have also been reported (7, 8). Studies in elderly patients have linked high IGFBP-2 levels with lower bone mass in this population (9–12), whereas other studies in humans suggested a possible link between IGFBP-2 and bone turnover (12). However, none of the human studies examined the concomitant relationship between IGFBP-2 and energy utilization, whole-body metabolism or estrogen sufficiency.

Based on these observations, our laboratory investigated the role of IGFBP-2 in bone remodeling using mice with a global knockout of the Igfbp2 gene. Igfbp2−/− male mice exhibited reduced bone mass due to decreased bone turnover, heavier body weight due to increased fat mass, and normal glucose homeostasis at 16 weeks of age. Female-null mice, on the other hand, had increased cortical bone mass with no changes in fat mass relative to control mice (13). These studies led us to postulate an important interaction between circulating estrogen levels and IGFBP-2 on target tissues such as bone and fat.

Previous studies have suggested that estrogen has effects on IGFBP-2. Igfbp2 expression was reported to be up-regulated by estrogen treatment in the hippocampus and the frontal cortex of ovariectomized rat models (14, 15). Additionally, estrogen treatment increases the production of IGFBP-2 in cultured cartilage cells (16). Furthermore, rat mammary glands treated with antiestrogens were found to have decreased expression of Igfbp2 (17). Finally, estrogen stimulates pleiotrophin, a growth factor that binds to protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type Z, polypeptide 1 (RPTPβ), a cell surface receptor phosphatase, that also binds to IGFBP-2, and IGFBP-2 binding to RPTPβ enhances osteoblast differentiation (18). Therefore, pleiotrophin binding to RPTPβ would provide an alternative pathway by which estrogen could maintain bone mass in the absence of IGFBP-2 (19). To explore the mechanism of this estrogen-IGFBP-2 interaction we subjected female Igfbp2−/− (−/−) mice and littermate controls (+/+) to either ovariectomy (OVX) or sham operation at 8 weeks of age. We then analyzed and killed mice at 20 weeks of age. Our studies suggest that interactions between estrogen and IGFBP-2 are essential for modulating not only bone mass, but body composition and whole-body energy metabolism.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Generation of the B6.129-Igfbp2tm1Jep strain, referred to as Igfbp2−/− mice, has been described previously (13, 20). All mice used in this study were produced and maintained in our research colony at Maine Medical Center Research Institute, where mice were housed in polycarbonate cages on sterilized paper bedding and maintained under 14-hour light, 10-hour dark cycles. Sterilized water and Teklad Global 18% Protein Rodent Diet (Harland Laboratories) were available ad libitum. At 8 weeks of age −/− and +/+ controls were subjected to either OVX or sham operation. Mice were then analyzed 12 weeks after surgery (20 wk of age) before killing, during which serum, bones and fat tissues were collected for further analysis. For each experiment, the numbers of mutant and control mice used are provided in Results. All experimental studies and procedures involving mice were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Maine Medical Center Research Institute.

Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA)

DXA for whole-body areal bone mineral density (g/cm2), areal bone mineral content (aBMC) (g), and body composition (lean mass, g and % body fat) exclusive of the head was performed using the PIXImus densitometer (GE-Lunar). Scans were performed on +/+ and −/− sham and OVX mice at 8 and 20 weeks of age. A phantom standard provided by the manufacturer was assessed each day for instrument calibration (21).

Microcomputed tomography (μCT)

Ex vivo quantification of femoral structure

Microarchitecture of distal trabecular bone and midshaft cortical bone were analyzed in femora from 20-week-old +/+ and −/− sham and OVX mice by high-resolution μCT (VivaCT-40, 10-μm resolution; Scanco Medical AG). Bones were scanned at an energy level of 55 kVp and intensity of 145 μA, as described previously (22). The VivaCT-40 is calibrated weekly using a phantom provided by Scanco. All scans were analyzed using manufacturer software (Scanco, version 4.05). Acquisition and analysis of μCT data were performed in accordance with published guidelines (23).

In vivo quantification of abdominal adiposity

For in vivo scans, mice were anesthetized with Avertin and positioned with both legs extended. The torso of each mouse was scanned at an isotropic voxel size of 76 μm (45 kV, 177 μA) with the VivaCT-40 scanner described above. Two-dimensional gray scale image slices were reconstructed into a 3-dimensional tomography. Scans were reconstructed between the proximal end of L1 and the distal end of L5. The head and feet were not scanned and/or evaluated because of the relatively low amount of adiposity in these regions, and to allow for a decrease in scan time and radiation exposure to the animals. The region of interest for each animal was defined based on skeletal landmarks from the gray scale images. The high resolution of this method allows for the imaging of both sc adipose tissue (SAT) and visceral adipose tissue (VAT). An automated algorithm was then used to quantify VAT and SAT using previously described methods (24, 25).

Histomorphometry

Static and dynamic histomorphometry were evaluated in 16-week-old +/+ and −/− sham or OVX mice. Mice were injected with 20-mg/kg calcein and 50-mg/kg demeclocycline ip 9 and 2 days, respectively, before sample collection. The proximal tibias were then analyzed as described previously (26), and standard nomenclature was used (27).

Serum protein measurements

Serum concentrations of fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), insulin, total procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide (P1NP), and collagen type 1 cross-linked c-telopeptide were measured using the mouse/rat FGF21 kit from R&D Systems, the ultrasensitive mouse insulin ELISA kit from Crystal Chem, Inc, the rat/mouse P1NP Enzyme Immunoassay and the RatLaps Enzyme Immunoassay from Immunodiagnostic Systems, Inc. The assay sensitivities were ±3.81 pg/mL, ±0.05 ng/mL, ±0.7 ng/mL, and ±2 ng/mL, respectively. The intraassay variations were 4.3 pg/mL, ≤10 ng/mL, 6.3 ng/mL, and 6.3%–6.9% and the interassay variations were 6.7 pg/mL, ≤10 ng/mL, 8.5 ng/mL, and 8.5%–12%. Serum concentrations of leptin and IGFBP-2 were measured using ELISA kits from ALPCO Diagnostics. The sensitivities of the assay were ±10 pg/mL and ±0.01 ng/mL, respectively. The intraassay coefficients of variation were less than 4.4% and 5%, and the interassay coefficients of variation were less than 4.7% and 5%. All measurements were performed in duplicate.

Glucose measurement and insulin tolerance tests

At 20 weeks of age, +/+ and −/− sham and OVX mice were evaluated for fasted blood glucose levels and insulin tolerance. For analysis of blood glucose, mice were fasted overnight, and then glucose levels were measured using the OneTouch Ultra Glucometer (LifeScan, Inc) as described previously (28). For the insulin tolerance test, mice were fed ad libitum and injected ip with insulin at a dose of 1 U/kg. Glucose levels were then measured at 0, 20, 40, 60, and 120 minutes after injection.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was prepared using a standard TRIzol (Life Technologies) method for tissues. A total of 500 ng of RNA was then converted to cDNA in a reverse transcription reaction using the MessageSensor RT kit (Life Technologies) and random decamers as primers. The cDNA was then diluted 1:5 with water. Quantification of mRNA expression was carried out using an iQ SYBR Green Supermix in a iQ5 thermal cycler and detection system (Bio-Rad). A geNorm kit was used to determine the most stable housekeeping genes for each tissue (PrimerDesign). Primers were designed and tested to be 95%–100% efficient by PrimerDesign. Primer sequences are available in Supplemental Table 1.

Metabolic cage analysis

Indirect calorimetry measurements were performed using the Promethion Metabolic Cage System (Sable Systems) located in the Physiology Core Department of Maine Medical Research Institute. Data acquisition and instrument control were performed using the MetaScreen software version 2.2.18, and the obtained raw data were processed using ExpeData version 1.8.2 (Sable Systems) using an analysis script detailing all aspects of data transformation. Mice were subjected to a standard 12-hour light, 12-hour dark cycle during the study, which consisted of a 12-hour acclimation period followed by a 72-hour sampling duration. Data shown are representative of the 24-hour average of this period. Each cage in the 16-cage system consists of a cage with standard bedding, a food hopper, water bottle, and “house-like enrichment tube” for body mass measurements, connected to load cells for continuous monitoring, as well as a 11.5-cm running wheel connected to a magnetic reed switch to record revolutions. Ambulatory activity and position were monitored using the XYZ beam arrays with a beam spacing of 0.25 cm. From this data animal pedestrian locomotion and speed within the cage were calculated. Respiratory gases were measured using the GA-3 gas analyzer (Sable Systems) using a pull-mode, negative-pressure system. Air flow is measured and controlled by the FR-8 (Sable Systems), with a set flow rate of 2000 mL/min. O2 consumption (VO2) and CO2 production (VCO2) were reported in milliliters per minute. Water vapor is continuously measured and its dilution effect on O2 and CO2 are mathematically compensated for in the analysis stream (see reference 36 below). Energy expenditure (EE) was calculated using the Weir equation: kcal/h = 60 × (0.003941 × VO2 + 0.001106 × VCO2) and respiratory quotient (RQ) was calculated as the ratio of VCO2/VO2. Ambulatory activity and wheel running were determined simultaneously with the collection of the calorimetry data. Thus resting EE (REE) was able to be determined and is calculated as the average EE of 30-minute intervals of no activity. Sleep hours were determined as any inactivity lasting greater than 40 seconds or more (29). Correlations were performed between EE and lean, fat, and total body mass to determine whether these variables could explain changes in EE. No significant correlations were found between EE and any of the variables thus EE, is reported in kcal/h (Supplemental Figure 1) (30–32).

Whole tissue VO2 rate (OCR)

Adipose tissue OCR from 20-week-old mice was analyzed using the XF24 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience) as described elsewhere (33). Briefly, freshly isolated brown adipose tissue (BAT) and inguinal white adipose tissue (IWAT) were isolated, cut into approximately 10-mg pieces, washed thoroughly in unbuffered Krebs-Henseleit Buffer media containing 111mM NaCl, 4.7mM KCl, 2mM MgSO4, 1.2mM Na2HPO4, 0.5mM carnitine, and 2.5mM glucose and then placed in a single well of a XF24-well Islet capture microplate (Seahorse Bioscience) containing 500 μL of Krebs-Henseleit Buffer media. Each tissue was then covered with an islet capture screen, which allows for free perfusion within the well while restricting tissue movement. The samples were then analyzed for OCR using the next protocol after calibration and equilibration: 4 cycles of mix 3 minutes, wait 2 minutes, measure 3 minutes for basal values, then injected with 10mM sodium pyruvate and measured for 6 cycles of mix 3 minutes, wait 2 minutes, measure 3 minutes. Postrun tissues were then homogenized, protein extracted, and quantified using a bicinchoninic acid assay kit (Bio-Rad). OCR values were then normalized to total protein content per well to account for differences in adipocyte size (Supplemental Figure 2). Data presented for the XF24 experiments are representative of 3 independent experiments with 5 replicate wells per genotype/treatment within each experiment.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Results were analyzed for statistically significant differences using a two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak's multiple comparison post hoc test. All statistics, including regression analysis, were performed with Prism 6 statistical software (GraphPad Software, Inc). Statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

OVX−/− mice have less of an increase in intraabdominal fat but greater bone loss than OVX+/+ mice

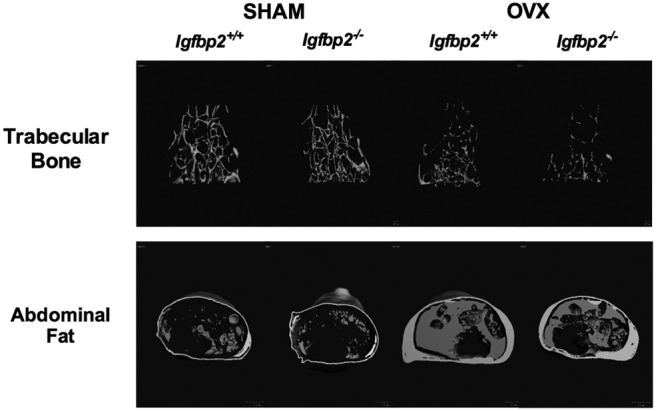

Serum IGFBP-2 levels were reduced with OVX in +/+ mice (sham, 823.1 ± 47.3 vs OVX, 567.4 ± 57.1 ng/mL; P < .05). With OVX, null and control mice gained weight as predicted, compared with sham mice. However, after OVX−/− females weighed less compared with OVX+/+ controls. This difference was attributable to less of an increase in body fat as determined by DXA (Table 1). In vivo μCT analysis of the abdominal compartment confirmed this difference in total adipose tissue mass with significantly less VAT, and to a lesser extent SAT compared with OVX+/+ (Table 1 and Figure 1). As expected, DXA analysis revealed bone loss in both genotypes with OVX; however, OVX−/− mice lost a greater percentage of aBMC compared with OVX+/+ mice (% change: OVX+/+, −11% vs OVX−/−, −17%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Body Composition of 20-Week-Old (12 wk After Surgery) Igfbp2+/+ and Igfbp2−/− OVX and Sham Control Mice

| Sham |

OVX |

Two-way ANOVA P Value |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +/+ | −/− | +/+ | −/− | Interaction | Genotype | Treatment | |

| Body weight (g) | 22.78 ± 0.37 | 23.41 ± 0.28 | 30.14 ± 0.64b | 27.01 ± 0.35c,d | <0.0001 | 0.0055 | <0.0001 |

| aBMC (g) | 0.417 ± 0.006 | 0.457 ± 0.008a | 0.371 ± 0.008b | 0.379 ± 0.007c | 0.0314 | 0.0015 | <0.0001 |

| Lean (g) | 18.81 ± 0.31 | 19.44 ± 0.32 | 20.14 ± 0.26b | 19.76 ± 0.40 | 0.1119 | 0.7733 | 0.0178 |

| Fat (g) | 2.94 ± 0.23 | 2.77 ± 0.16 | 9.02 ± 0.62b | 6.45 ± 0.39c,d | 0.0035 | 0.001 | <0.0001 |

| TAT (/mm3) | 464.57 ± 47.01 | 404.72 ± 32.06 | 2060.11 ± 98.5b | 1206.61 ± 94.2c,d | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| VAT (/mm3) | 169.51 ± 31.64 | 119.18 ± 19.12 | 1270.85 ± 84.72b | 589.84 ± 63.08c,d | 0.0287 | 0.0448 | <0.0001 |

| SAT (/mm3) | 295.07 ± 16.38 | 285.54 ± 13.47 | 789.26 ± 59.01b | 616.76 ± 36.19c,d | 0.0306 | 0.0164 | <0.0001 |

TAT, total adipose tissue abdominal region; VAT, VAT abdominal region; SAT, SAT abdominal region. n = 16 per genotype/treatment.

P < .05 sham +/+ vs sham −/−.

P < .05 sham +/+ vs OVX+/+.

P < .05 sham −/− vs OVX−/−.

P < .05 OVX+/+ vs OVX+/+.

Figure 1.

μCT images of the distal femoral trabeculae (top) and abdominal fat (bottom) of Igfbp2+/+ and Igfbp2−/− sham and OVX mice at 20 weeks of age.

The higher bone loss seen in the OVX−/− mice is attributable to increased resorption and decreased bone formation

To define the skeletal changes more precisely, we performed high resolution μCT imaging and dynamic histomorphometry. μCT analysis of the femur confirmed that with OVX, both genotypes had significant decreases in both trabecular and cortical bone volume; however, OVX−/− mice lost more trabecular bone than +/+ controls (% change bone volume/total volume: +/+ −48% vs −/− −76%) (Table 2 and Figure 1). Furthermore OVX−/− mice had a greater percentage of cortical bone loss (% change cortical thickness: +/+ −6% vs −10% −/−) (Table 2) confirming the changes in bone observed by DXA. This difference in cortical bone loss can be attributed to the periosteal expansion of the cortical region measured by total area (Tt.Ar), which was suppressed with OVX in the Igfbp2−/− mice.

Table 2.

μCT Structural Analysis of the Femur of 20-Week-Old (12 wk After Surgery) Igfbp2+/+ and Igfbp2−/− OVX and Sham Control Mice

| Sham |

OVX |

Two-way ANOVA P Value |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +/+ | −/− | +/+ | −/− | Interaction | Genotype | Treatment | |

| Distal femur | |||||||

| %BV/TV | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 5.1 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.2b | 1.2 ± 0.2cd | 0.0026 | 0.2118 | <0.0001 |

| Conn.D (L/mm3) | 47.63 ± 2.58 | 51.04 ± 2.71 | 6.81 ± 1.03b | 2.68 ± 0.64c,d | 0.292 | 0.3422 | <0.0001 |

| SMI | 3.01 ± 0.05 | 2.97 ± 0.05 | 3.73 ± 0.08b | 3.99 ± 0.13c,d | 0.1891 | 0.27 | <0.0001 |

| Tb.N (mm−1) | 2.98 ± 0.05 | 2.99 ± 0.04 | 2.01 ± 0.08b | 1.64 ± 0.11c,d | <0.001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Tb.Th (mm) | 0.041 ± 0.001 | 0.044 ± 0.001 | 0.040 ± 0.001 | 0.044 ± 0.002 | 0.667 | 0.041 | 0.638 |

| Tb.Sp (mm) | 0.322 ± 0.06 | 0.333 ± 0.004 | 0.478 ± 0.016b | 0.667 ± 0.048c,d | 0.0008 | 0.0002 | <0.0001 |

| Femur midshaft | |||||||

| Ct.Th (mm) | 0.218 ± 0.002 | 0.232 ± 0.002a | 0.205 ± 0.001b | 0.209 ± 0.001c | 0.0015 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Tt.Ar (mm2) | 1.77 ± 0.02 | 1.87 ± 0.02a | 1.80 ± 0.02 | 1.78 ± 0.02c | 0.0041 | 0.0847 | 0.1984 |

| Ct.Ar (mm2) | 0.873 ± 0.009 | 0.944 ± 0.009a | 0.838 ± 0.009 | 0.841 ± 0.008c | 0.0041 | 0.0867 | 0.2052 |

| %Tt.Ar/Ct.Ar | 49.3 ± 0.3 | 50.6 ± 0.4a | 46.5 ± 0.2b | 47.3 ± 0.4c | 0.4433 | 0.0014 | <0.0001 |

| Ma.Ar (mm2) | 0.899 ± 0.014 | 0.921 ± 0.014a | 0.967 ± 0.012 | 0.939 ± 0.015 | 0.0812 | 0.8441 | 0.0029 |

%BV/TV, bone volume/total volume; Conn.D, connectivity density; SMI, structural model index; Tb.N, trabecular number; Tb.Th, trabecular thickness; Tb.Sp, trabecular spacing; Ct.Th, cortical thickness; Ct.Ar, cortical area; Tt.Ar, total area; Ma.Ar, marrow area. n = 16 per treatment/genotype.

P < .05 +/+ sham vs −/− sham.

P < .05 +/+ sham vs +/+ OVX.

P < .05 −/− sham vs −/− OVX.

P < .05 +/+ OVX vs −/− OVX.

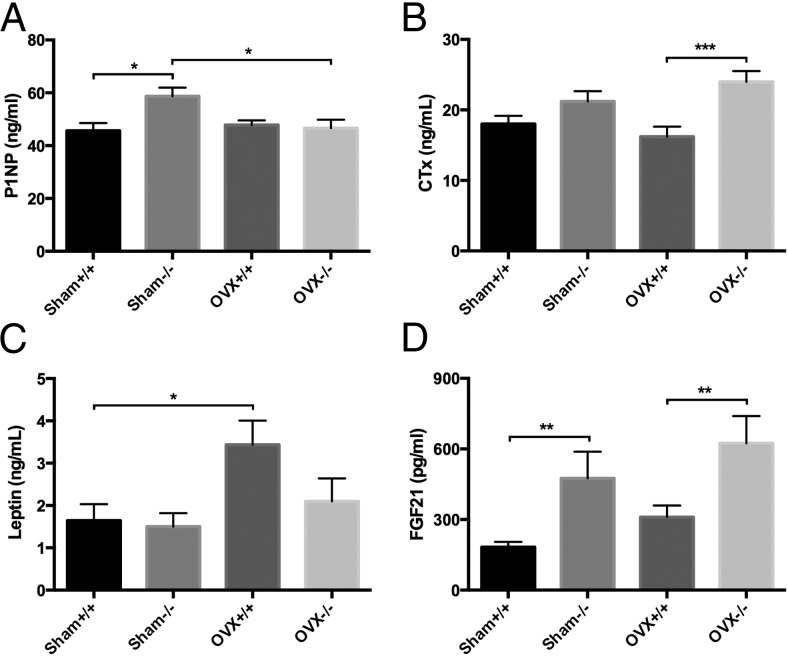

Histomorphometry of the proximal tibia revealed that OVX−/− tibias had significant decreases in mineral apposition rates compared with both sham −/− and OVX+/+ tibias, despite having no significant changes in osteoblast number/bone perimeter (Table 3). Likewise, bone formation rates were also reduced in the OVX−/− tibias compared with sham −/− tibias. In addition, osteoclast number/bone perimeter in the OVX−/− tibias was significantly higher than sham −/− tibias and nearly doubled compared with OVX+/+ tibias (Table 3). Furthermore, serum P1NP, a marker of bone formation, was significantly reduced in OVX−/− mice compared with sham −/− controls (P < .007) (Figure 2A), whereas serum collagen type 1 cross-linked c-telopeptide, a marker of bone resorption, was elevated in the OVX−/− mice compared with OVX+/+ (P < .002) (Figure 2B). These data, as well as the structural and histomorphometric data, suggest that the higher bone loss seen in the OVX−/− mice is due to unbalanced remodeling in the form of increased resorption and decreased bone formation.

Table 3.

Histomorphometric Analysis of the Proximal Tibia at 16 Weeks of Age (8 wk After Surgery) in Igfbp2+/+ and Igfbp2−/− OVX and Sham Mice

| Sham |

OVX |

Two-way ANOVA P Value |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +/+ | −/− | +/+ | −/− | Interaction | Genotype | Treatment | |

| MAR (mm/d) | 1.48 ± 0.16 | 1.86 ± 0.15 | 1.57 ± 0.13 | 1.05 ± 0.01c,d | 0.003 | 0.6057 | 0.015 |

| BFR/BS (mm3/μm2 per y) | 251.7 ± 34.6 | 334.1 ± 29.5 | 233.2 ± 27.7 | 185.4 ± 5.7c | 0.0232 | 0.4707 | 0.0055 |

| N.Ob/B.Pm (/mm) | 8.71 ± 0.96 | 7.93 ± 1.29 | 5.41 ± 0.75 | 6.27 ± 0.91 | 0.4307 | 0.9667 | 0.0253 |

| N.Oc/B.Pm (/mm) | 4.34 ± 0.55 | 4.15 ± 0.47 | 6.37 ± 0.38 | 11.19 ± 1.56c,d | 0.0069 | 0.0113 | <0.0001 |

| N.Ad/Tt.Ar (#/mm2) | 20.3 ± 4.7 | 18.4 ± 2.0 | 105.4 ± 18.8b | 121.0 ± 15.0c | 0.4965 | 0.5939 | <0.0001 |

MAR, mineral apposition rate; BFR/BS, bone formation rate/bone surface; N.Ob/B.Pm, number of osteoblasts/bone perimeter; N.Oc/B.Pm, number of osteoblasts/bone perimeter; N.Ad/Tt.Ar, number of adipocytes/Tt.Ar. n = 5–6 per genotype/treatment.

P < .05 sham +/+ vs sham −/−.

P < .05 sham +/+ vs OVX+/+.

P < .05 sham −/− vs OVX−/−.

P < .05 OVX+/+ vs OVX+/+.

Figure 2.

Serum protein measurements. A, P1NP (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.0187, genotype = 0.0478, treatment = 0.0959). B, Collagen type 1 cross-linked c-telopeptide (CTx) (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.1081, genotype = 0.0003, treatment = 0.7259). C, Leptin (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.2156, genotype = 0.1288, treatment = 0.0171). D, FGF21 (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.8983, genotype = 0.0009, treatment = 0.1066). For all assays, n = 9–10 per genotype/treatment; *, P < .05; **, P < .001; ***, P < .0001.

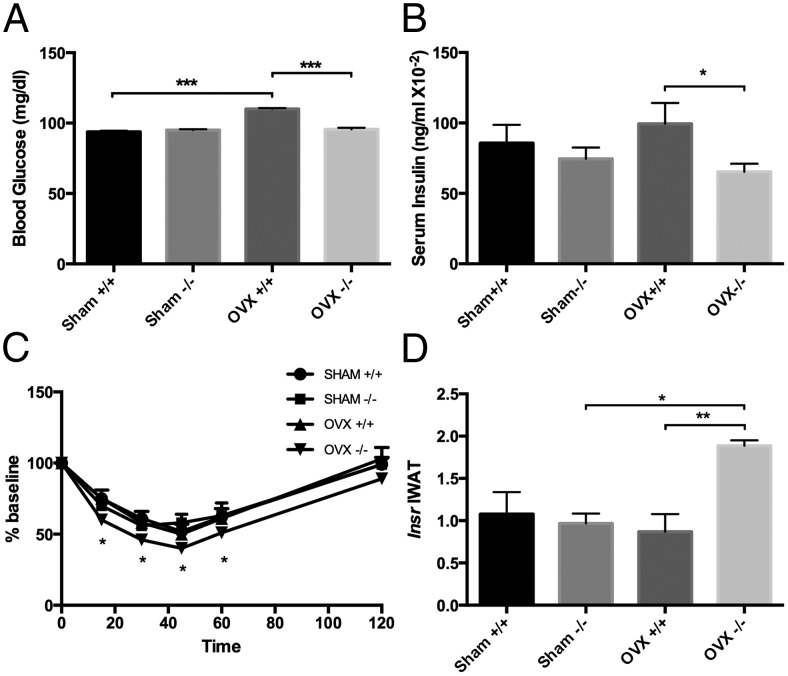

OVX−/− mice are protected from OVX-induced decreases in insulin sensitivity

To assess whether the lack of IGFBP-2 and OVX had an effect on glucose homeostasis we measured fasting glucose levels, insulin levels and performed an insulin tolerance test. With fasting, OVX+/+ mice had increased glucose relative to sham +/+ controls and OVX−/− mice (P < .0001) (Figure 3A), whereas serum glucose remained unchanged in the OVX−/− mice. On the other hand serum insulin levels were found to be significantly decreased in the OVX−/− mice compared with OVX+/+ mice (P < .05) (Figure 3B). Insulin tolerance tests revealed increased insulin sensitivity in the OVX−/− mice with compared with the OVX+/+ mice (P < .05) (Figure 3C). Likewise gene expression analysis of the IWAT depot revealed significant increases in the expression of the Insr in OVX−/− mice vs OVX+/+ (P < .004) (Figure 3D) pointing to one possible mechanism whereby insulin sensitivity was increased. Furthermore serum FGF21, known for its insulin-sensitizing properties, was increased in the sham and OVX−/− mice relative to control +/+ mice (P < .001) (Figure 2D). Taken together, these data suggest that mice ovariectomized in the absence of IGFBP-2 are protected from OVX-induced decreases in insulin sensitivity (34).

Figure 3.

Analysis of glucose homeostasis in Igfbp2+/+ and Igfbp2−/− sham and OVX mice at 20 weeks of age. A, Fasted blood glucose levels (two-way ANOVA: interaction < 0.0001, genotype < 0.0001, treatment < 0.0001). B, Serum insulin levels (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.2573, genotype = 0.0362, treatment = 0.9090). C, Insulin tolerance test (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.2797, genotype = 0.0480, treatment = 0.3696). D, IWAT expression of Insr (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.0085, genotype = 0.0265, treatment = 0.0704). n = 6 per genotype/treatment; *, P < .05; **, P < .001; ***, P < .0001.

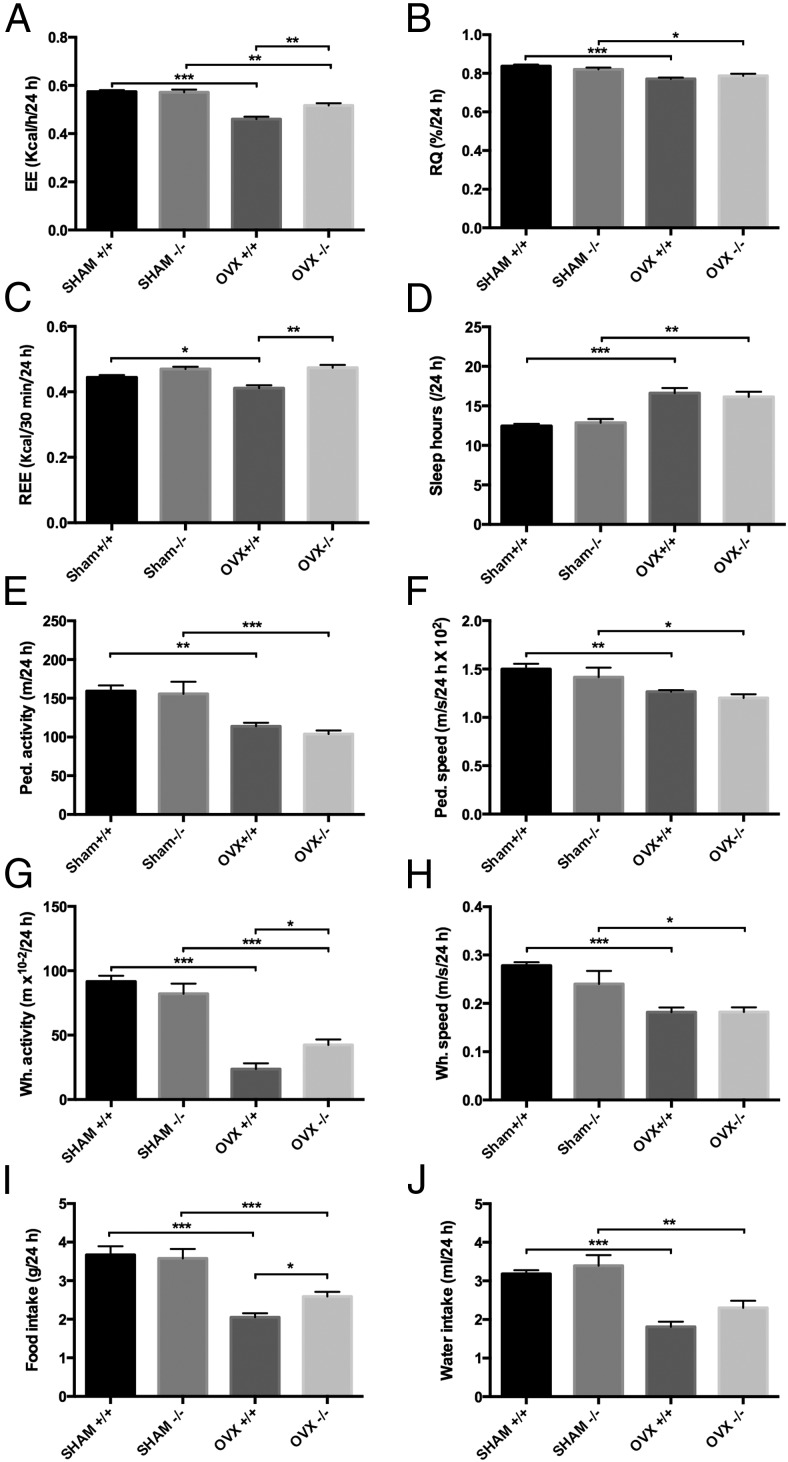

OVX−/− mice exhibit higher EE and activity levels than OVX+/+

To more fully understand the mechanisms responsible for the greater insulin sensitivity but higher bone loss in OVX−/− mice, we examined EE using metabolic chambers. OVX resulted in a reduction in EE in both genotypes vs sham (P < .0001). Remarkably, the OVX−/− mice had a significantly higher EE rate than the OVX+/+ controls (OVX+/+, 0.460 ± 0.010 kcal/h vs OVX−/−, 0.517 ± 0.010 kcal/h; P = .0003) (Figure 4A). RQs were reduced in both genotypes with OVX (P < .0001) (Figure 4B), suggesting that OVX causes a shift toward fatty acid oxidation rather than carbohydrate utilization. REE was reduced in the OVX+/+ mice compared with sham +/+ controls (P < .02) and OVX−/− mice (P < .0001), whereas interestingly, no changes in REE were noted in the OVX−/− mice compared with sham −/− controls (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Metabolic cage analysis of Igfbp2+/+ and Igfbp2−/− sham and OVX mice at 20 weeks of age. A, EE (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.0041, genotype = 0.0104, treatment < 0.0001). B, RQ (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.0759, genotype = 0.9741, treatment < 0.0001). C, REE (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.0341, genotype < 0.0001, treatment = 0.0908). D, Sleep hours (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.4580, genotype = 0.9787, treatment < 0.0001). E, Pedestrian activity (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.6840, genotype = 0.3947, treatment < 0.0001). F, Pedestrian speed (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.8724, genotype = 0.1557, treatment = 0.0002). G, Wheel activity (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.0111, genotype = 0.3909, treatment < 0.0001). H, Wheel speed (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.1660, genotype = 0.1703, treatment < 0.0001). I, Food intake (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.0741, genotype = 0.2013, treatment < 0.0001). J, Water intake (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.4309, genotype = 0.0545, treatment < 0.0001). n = 16 per genotype/treatment; *, P < .05; **, P < .001; ***, P < .0001.

With OVX, the amount of sleep acquired over a 24-hour period in both genotypes was increased (P < .0001) (Figure 4D). Pedestrian activity (calculated as meters walked within the cage) as well as speed of walking were reduced in both genotypes with OVX (P < .0003) (Figure 4, E and F). Likewise wheel running and speed were also significantly reduced with OVX in both genotypes (P < .0001) (Figure 4, G and H). However, OVX−/− mice ran almost twice as much on the wheel as OVX+/+ mice (P < .03). Food consumption was reduced in both genotypes with OVX (P < .0001) (Figure 4I), as was water intake (P < .0001) (Figure 4J). However, OVX−/− mice consumed more food than OVX+/+ mice despite the fact that the Igfbp2 −/− mice gained less weight after OVX than +/+ mice (P < .05).

Due to differences in food consumption and EE with OVX between genotypes, serum leptin, an adipose-derived hormone also known for its effects on appetite was measured (35). OVX had a significant effect on leptin levels (P < .02), with OVX+/+ serum leptin levels 52% higher than sham controls (P < .03) (Figure 2C). On the other hand there was a 28% but nonsignificant increase in leptin in the OVX−/− vs sham −/− serum, corresponding with the lower fat mass increase in these animals compared with OVX+/+ controls (Table 1). The decreased food consumption observed in the OVX+/+ mice compared with OVX−/− mice is likely due to the increased leptin levels observed.

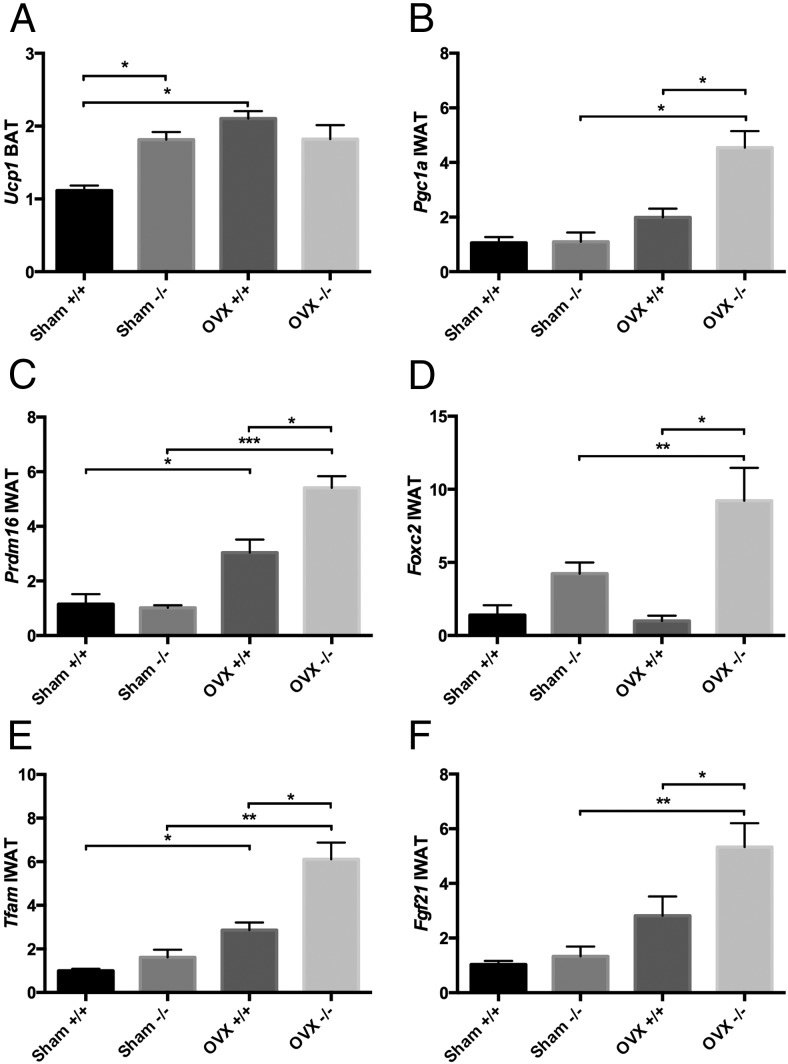

OVX−/− mice have increased browning of white adipocyte depots

Having established genotype specific differences in fat mass and EE after OVX, we sought to define whether there was an increase in sympathetic tone driving preformed interscapular BAT or brown-like adipogenesis in peripheral depots. We measured by real time quantitative real-time PCR, the expression of a number of key thermogenic genes in BAT as well as the IWAT depots. Analysis of the BAT revealed no changes in the expression of any thermogenic genes except Ucp1, which was increased in the OVX+/+ vs sham controls (P < .0004), whereas no changes in expression were seen in the OVX−/− BAT (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Relative expression of (A) Ucp1 in brown fat (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.0019, genotype = 0.1064, treatment = 0.0017) and (B–F) Pgc1a (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.0083, genotype = 0.0071, treatment = 0.0002), Prdm16 (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.0055, genotype = 0.0110, treatment < 0.0001), Foxc2 (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.0522, genotype = 0.0008, treatment = 0.0906), Tfam (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.0631, genotype = 0.0070, treatment < 0.0001), and Fgf21 (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.0882, genotype = 0.0358, treatment = 0.0004) in inguinal fat in Igfbp2+/+ and Igfbp2−/− sham and OVX mice at 20 weeks of age; n = 8 per genotype/treatment; *, P < .05; **, P < .001; ***, P < .0001.

IWAT is a depot known to have the capacity to brown under certain circumstances (36). As such, we profiled several genes that have been associated with “brown-like” adipogenesis. Pgc1a is a coactivator of mitochondrial biogenesis and function and a driver of WAT browning (37); its expression in OVX−/− IWAT was increased 4-fold compared with sham −/− (P < .0004) and was 2-fold higher than OVX+/+ (P < .003) (Figure 5B). Further, Prdm16, a transcriptional cofactor and master regulator of WAT browning and BAT function (38), was increased with OVX (P < .0001), but in the OVX−/− mice, expression was 3-fold higher vs sham −/− and 1.5-fold higher than OVX+/+ (P < .05) (Figure 5C). Additionally, Foxc2, another protein implicated in the browning process and in Tfam activation specifically (39), was 2-fold up-regulated in OVX−/− mice compared with sham −/− (P < .04) and 11-fold compared with OVX+/+ (P < .002) (Figure 5D). Not surprisingly, expression of Tfam, a mitochondrial transcription factor, was increased with OVX (P < .0001), with OVX−/− expression 4-fold higher than sham −/− (P < .0002) and 2-fold higher than OVX+/+ (P < .006) (Figure 5E). In addition, Fgf21 which is known to up-regulate thermogenic genes and Pgc1a in particular (40) in the browning process of WAT, was up-regulated 4-fold in OVX−/− mice compared with sham −/− (P < .001) and 2-fold compared with OVX+/+ (P < .03) (Figure 5F). These data suggest that with OVX, thermogenesis in the IWAT depot attempts to compensate for the lack of up-regulation of Ucp1 in the BAT depot in the Igfbp2-null mice.

The OVX−/− IWAT depot is more metabolically active than OVX+/+ IWAT and greater BAT VO2 is consistent with Ucp1 expression patterns

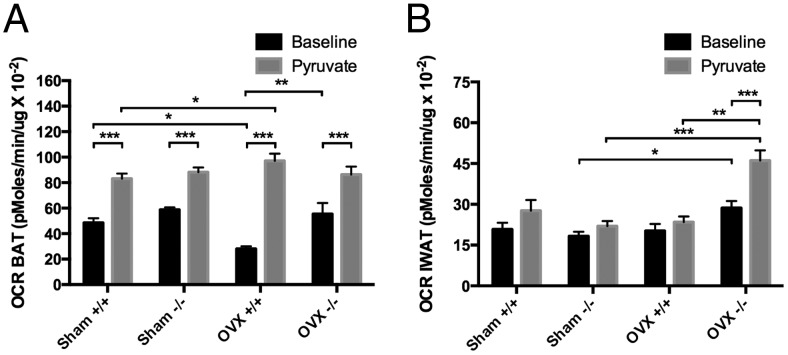

To determine whether the up-regulation of these thermogenic genes resulted in more metabolically active adipose tissue, we then analyzed 10-mg slices of BAT and IWAT on the Seahorse XF24 analyzer at baseline (in the presence of 2.5mM glucose) and after sodium pyruvate stimulation (10mM) for OCRs. In BAT tissue at baseline, OCR in the OVX+/+ BAT was lower than sham +/+ (P < .003) and OVX−/− BAT (P < .0001), whereas no significant differences were noted between sham −/− and OVX−/−. Not surprisingly, with pyruvate stimulation, OCR went up in all samples (P < .0001); however, the OVX+/+ had an increase of 76% compared with baseline whereas the OVX−/− BAT only increased by 36%, suggesting that the increased Ucp1 expression might compensate for a lower metabolic rate in the OVX+/+ mice (Figure 6A). On the other hand, analysis of the IWAT depot revealed that OVX−/− IWAT had a higher OCR at baseline compared with sham −/− (P < .04). With pyruvate stimulation the OVX−/− IWAT had a 38% increase in OCR compared with baseline (P < .0003) and a 49% increase over pyruvate-stimulated OVX+/+ IWAT (P < .0001) (Figure 6B). These data, coupled with increased expression of a number of thermoregulatory genes, suggest that the OVX−/− mice have an increase in metabolic activity in the IWAT depot in response to OVX compared with +/+ mice.

Figure 6.

OCR of (A) brown fat (two-way ANOVA: interaction = 0.0010, genotype < 0.0001, treatment = 0.3327) and (B) inguinal fat (two-way ANOVA: interaction < 0.0001, genotype = 0.0002, treatment = 0.0005) in Igfbp2+/+ and Igfbp2−/− sham and OVX mice at basal (2.5mM glucose) and pyruvate-loaded (10mM) conditions (*, P < .05; **, P < .001; ***, P < .0001). Data are representative of 5 wells per genotype/treatment; 3 experiments in replicate.

Discussion

Our laboratory had previously focused studies on IGFBP-2 actions in the skeleton because of the dramatic skeletal phenotype of the male Igfbp2−/− mice. However, it soon became apparent that female Igfbp2−/− mice exhibited preservation of trabecular bone and higher cortical bone pointing to an estrogen dependent pathway that prevented bone loss and/or increased acquisition of peak bone mass. In this study, we hypothesized that estrogen sufficiency protected the skeleton of Igfbp2 global knockout mice, and that there was an important interaction between IGFBP-2 and estrogen. First, we found that with OVX in the +/+ mice, serum IGFBP-2 levels were reduced, indicative of a positive interaction between IGFBP-2 production and estrogen levels. Second relative to +/+ controls, OVX−/− females had significantly greater loss of trabecular and cortical bone mass. On the other hand, OVX−/− mice gained less fat mass than OVX+/+ and had a marked increase in insulin sensitivity coupled with higher EE, due to a browning of the inguinal depot and greater serum levels of FGF21 and enhanced adipocyte expression of Fgf21.

The OVX−/− females exhibited greater trabecular and cortical bone loss compared with controls despite having slightly higher basal bone mass because of a greater degree of imbalance in the bone remodeling unit. Both OVX+/+ and −/− mice lost trabecular and cortical bone mass, which was almost certainly related to an increase in bone resorption from greater numbers of osteoclasts per bone perimeter (see Table 3). However, the effect was much greater in respect to loss of bone volume fraction and trabecular number (Table 2) in the OVX−/− mice and this was attributable to a concomitant reduction in bone formation and mineral apposition. Several lines of evidence from our studies support the precept that there is a synergistic effect from loss of both estrogen and IGFBP-2 on bone remodeling. First, our studies and others have shown a strong relationship between IGFBP-2 and osteoblast differentiation and bone formation (8, 41–43). We observed that, in males, loss of IGFBP-2 was associated with a marked reduction in bone formation. It has also been reported that MC3T3 cells have increased IGFBP-2 expression during differentiation (44) and several factors have been shown to increase IGFBP-2 expression in these cells (45, 46). Secondly, we recently showed that IGFBP-2 directly stimulates osteoblast differentiation and hastens mineralization in the absence of other differentiation factors (47). Finally, estrogen increases pleiotrophin, a growth factor for osteoblasts that binds to RPTPβ, which is also the extracellular receptor for IGFBP-2 (18, 19). Hence, in the absence of both IGFBP-2 and estrogen, there may be an additive loss of several differentiating signals for the osteoblast. Notwithstanding, it should be noted that enhanced sympathetic signaling could also uncouple remodeling with a decrease in formation and an increase in resorption. Our whole-body metabolic studies suggest that a relative increase in sympathetic activity may indeed contribute to bone loss and at the same time increase insulin sensitivity. Specifically, OVX−/− mice have higher insulin sensitivity, whole-body EE, greater VO2 in inguinal fat depots as well as gene expression markers of brown-like adipogenesis, and significantly less abdominal fat, seemingly all positive effects, yet they exhibit greater bone loss than OVX+/+ mice (Tables 1–3 and Figures 3–6).

Indeed, one of the surprising findings in our studies was that OVX−/− mice exhibited higher EE and increased motor activity, as well as up-regulation of a number of thermogenic genes in the inguinal fat depot compared with OVX+/+ mice. In humans and in mice, OVX is invariably associated with an increase in abdominal and marrow adiposity, and this includes down-regulation of EE (see Figure 4). The up-regulation of thermogenic genes in the inguinal depot of OVX−/− mice is indicative of a “browning” or beige fat phenotype (36). Furthermore, tissue from inguinal fat pads exhibited increased oxidative phosphorylation at baseline and poststimulation, suggesting that these fat depots not only express “beige” genes, but are more metabolically active than their +/+ controls. In the BAT depot, we saw increased levels of Ucp1 in the sham −/− mice vs +/+, suggesting that the absence of IGFBP-2 alone enhances brown adipocyte function in female mice and is consistent with previous findings in humans (10).

Despite the decrease in EE after OVX in +/+ mice, we saw an increase in Ucp1 expression in the OVX+/+ BAT, supporting previous reports of increased UCP1 protein expression in BAT from ovariectomized rats (48). On the other hand, in the OVX−/− BAT, there was no change in Ucp1 expression or VO2 relative to sham control, suggesting that these tissues may already be at their highest metabolic rate due to the absence of IGFBP-2. However, with the absence of estrogen and IGFBP-2, there was “browning” of the inguinal depot coinciding with less post-OVX weight gain, increased insulin sensitivity, and lower intraabdominal fat. It is conceivable that the OVX−/− mice are compensating for the lack of response in BAT with increased sympathetic activity directed in the inguinal fat stores. It is also possible that the opposite is true; because there is increased sympathetic tone in the inguinal fat stores, perhaps preformed BAT does not need to compensate for the decrease in EE seen with OVX. Regardless, increased sympathetic tone leads to increased catecholamine release, which through binding to the β2 adrenergic receptor would also restrain bone formation and increase osteoclastogenesis resulting in the marked decrease in bone mass in the OVX−/− mice (36, 49–51).

A number of factors were examined that could potentially mediate the putative cell nonautonomous effects on adipose depots and the skeleton. We found that Foxc2 and Fgf21 IWAT expression were both increased significantly (see Figure 5) in the OVX−/− mice, both known for having insulin-sensitizing/browning effects on WAT. First, Foxc2 has been shown to increase browning of WAT, increasing EE through its effects on Tfam among other mitochondrial transcription factors (39, 52). Foxc2 also has insulin-sensitizing properties and is anabolic for bone; however, the skeletal effects were dependent on the up-regulation of both wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 10B and IGFBP-2 (50). Even more striking, IGFBP-2 was found to be 10-fold up-regulated in overexpressing Foxc2 mice (53). In our study, we saw a 4-fold increase in Foxc2 IWAT expression in the sham −/− vs sham +/+ mice, and with OVX, there is an 8-fold difference between genotypes (Figure 5). These data suggest that IGFBP-2 is a negative regulator of Foxc2 and that estrogen may be a key factor in this process.

Second, FGF21 is a hormone that has profound effects on glucose and lipid homeostasis, browning of WAT and EE (54). FGF21 is primarily produced in the liver; however, recent studies have shown that FGF21 expression in adipose tissue is required for the beneficial metabolic effects of this hormone (55, 56). Further it has been shown that hepatic FGF21 is required for its effects on lipid metabolism, whereas it is not needed for the insulin-sensitizing effects which are mediated through its actions on BAT and browning of WAT with subsequent increases in EE (57). Interestingly, the same study revealed that FGF21 treatment increased Igfbp-2 expression in the liver. In our study, Fgf21 expression levels in OVX−/− IWAT were increased 2-fold relative to OVX+/+ (Figure 5). It is plausible that this increased Fgf21 expression is responsible in part for the increased insulin sensitivity, browning of WAT and increased EE observed in the OVX−/− mice. Furthermore FGF21 serum levels were found to be increased in both Igfbp2−/− sham and OVX mice (Figure 2). These data in combination with the previously mentioned FGF21 treatment data suggest that IGFBP-2 may be involved in the regulation of FGF21. It is conceivable that increases in both Foxc2 expression and circulating FGF21 may be responsible for the browning of IWAT in OVX Igfbp2−/− mice; alternatively, these target genes may be induced by high sympathetic tone, which is enhanced in the central nervous system by a yet unknown factor.

There are several limitations in our current work. First, OVX not only reduces estrogen levels but also can alter or diminish other circulating hormones. Further studies are needed to determine whether the replenishment of estrogen to ovariectomized Igfbp2−/− mice will alter insulin sensitivity, body composition and EE. Second, the proposed inhibition of Forkhead box protein C2 by IGFBP-2 and the role of estrogen in this interaction warrant more attention using conditional mouse models. Third, the regulatory circuit for adipose derived FGF21 is different from FGF21 in the liver, which is the source for virtually all of the circulating FGF21. Moreover, we cannot exclude the possibility that higher circulating FGF21 levels in the OVX−/− mice could induce uncoupling in bone remodeling. This has previously been shown for lactation, a state in which estrogen deficiency is also evident (58). Finally, we cannot exclude the possibility that other endocrine and/or paracrine factors are responsible for the changes in whole-body homeostasis that we have observed in the OVX−/− mice.

In summary, we established that IGFBP-2 is an important determinant of body composition and whole-body metabolism both in the basal state and in response to OVX in female mice. Importantly, these data, taken in context with our previous studies in male Igfbp2−/− mice, highlight the importance of studying both genders in mice that have been genetically engineered, even when one sex has no overt phenotype. In our case, we found that the response of the skeleton and adipose tissue depots to OVX with and without IGFBP-2 is tissue-specific. Moreover, unlike male mice in which the presence of IGFBP-2 prevented insulin resistance and obesity (13, 59), female Igfbp2−/− mice that were ovariectomized showed a beneficial browning of inguinal adipose depots with less weight gain and greater insulin sensitivity. These data illustrate the strong interaction between estrogen and the IGFBP-2 regulatory system, which may be mediated via the putative IGFBP-2 receptor, RPTPβ (18). Further understanding of the role of IGFBP-2 in body composition by sex may lead to novel therapeutic targets for both osteoporosis and obesity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Casey R. Doucette and Katherine Motyl for critical review of this manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Grants AR-06114, AR063049, DK045227, and R24 DK092759-01. Additional support was provided by the Maine Medical Center Research Institute Physiology Core Facility as supported by NIH Grant P30 GM106391 to Don M. Wojchowski and the Small Animal Imaging Core Facility as supported by NIH Grant P30 GM103392 to Robert Friesel.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- aBMC

- areal bone mineral content

- BAT

- brown adipose tissue

- μCT

- microcomputed tomography

- CTx

- collagen type 1 cross-linked c-telopeptide

- DXA

- dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

- EE

- energy expenditure

- FGF21

- fibroblast growth factor 21

- IGFBP

- IGF-binding protein

- IWAT

- inguinal white adipose tissue

- OCR

- VO2 rate

- OVX

- ovariectomy

- P1NP

- procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide

- REE

- resting EE

- RPTPβ

- protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type Z, polypeptide 1

- RQ

- respiratory quotient

- SAT

- sc adipose tissue

- Tt.Ar

- total area

- VAT

- visceral adipose tissue

- VCO2

- CO2 production

- VO2

- O2 consumption.

References

- 1. Ricort JM. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein (IGFBP) signalling. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2004;14:277–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Conover CA. Insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins and bone metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;294:E10–E14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mohan S, Baylink DJ. IGF-binding proteins are multifunctional and act via IGF-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Endocrinol. 2002;175:19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fisher MC, Meyer C, Garber G, Dealy CN. Role of IGFBP2, IGF-I and IGF-II in regulating long bone growth. Bone. 2005;37:741–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hoeflich A, Nedbal S, Blum WF, et al. Growth inhibition in giant growth hormone transgenic mice by overexpression of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-2. Endocrinology. 2001;142:1889–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eckstein F, Pavicic T, Nedbal S, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-2 (IGFBP-2) overexpression negatively regulates bone size and mass, but not density, in the absence and presence of growth hormone/IGF-I excess in transgenic mice. Anat Embryol (Berl). 2002;206:139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Conover CA, Khosla S. Role of extracellular matrix in insulin-like growth factor (IGF) binding protein-2 regulation of IGF-II action in normal human osteoblasts. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2003;13:328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Palermo C, Manduca P, Gazzerro E, Foppiani L, Segat D, Barreca A. Potentiating role of IGFBP-2 on IGF-II-stimulated alkaline phosphatase activity in differentiating osteoblasts. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;286:E648–E657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Amin S, Riggs BL, Atkinson EJ, Oberg AL, Melton LJ, 3rd, Khosla S. A potentially deleterious role of IGFBP-2 on bone density in aging men and women. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:1075–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bredella MA, Fazeli PK, Lecka-Czernik B, Rosen CJ, Klibanski A. IGFBP-2 is a negative predictor of cold-induced brown fat and bone mineral density in young non-obese women. Bone. 2013;53:336–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lebrasseur NK, Achenbach SJ, Melton LJ, 3rd, Amin S, Khosla S. Skeletal muscle mass is associated with bone geometry and microstructure and serum insulin-like growth factor binding protein-2 levels in adult women and men. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:2159–2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Amin S, Riggs BL, Melton LJ, 3rd, Achenbach SJ, Atkinson EJ, Khosla S. High serum IGFBP-2 is predictive of increased bone turnover in aging men and women. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:799–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. DeMambro VE, Clemmons DR, Horton LG, et al. Gender-specific changes in bone turnover and skeletal architecture in igfbp-2-null mice. Endocrinology. 2008;149:2051–2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Takeo C, Ikeda K, Horie-Inoue K, Inoue S. Identification of Igf2, Igfbp2 and Enpp2 as estrogen-responsive genes in rat hippocampus. Endocr J. 2009;56:113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sárvári M, Kalló I, Hrabovszky E, et al. Estradiol replacement alters expression of genes related to neurotransmission and immune surveillance in the frontal cortex of middle-aged, ovariectomized rats. Endocrinology. 2010;151:3847–3862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Richmond RS, Carlson CS, Register TC, Shanker G, Loeser RF. Functional estrogen receptors in adult articular cartilage: estrogen replacement therapy increases chondrocyte synthesis of proteoglycans and insulin-like growth factor binding protein 2. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:2081–2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chan TW, Pollak M, Huynh H. Inhibition of insulin-like growth factor signaling pathways in mammary gland by pure antiestrogen ICI 182,780. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2545–2554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shen X, Xi G, Maile LA, Wai C, Rosen CJ, Clemmons DR. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF) binding protein 2 functions coordinately with receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase β and the IGF-I receptor to regulate IGF-I-stimulated signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:4116–4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hashimoto-Gotoh T, Ohnishi H, Tsujimura A, et al. Bone mass increase specific to the female in a line of transgenic mice overexpressing human osteoblast stimulating factor-1. J Bone Miner Metab. 2004;22:278–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wood TL, Rogler LE, Czick ME, Schuller AG, Pintar JE. Selective alterations in organ sizes in mice with a targeted disruption of the insulin-like growth factor binding protein-2 gene. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:1472–1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Delahunty KM, Shultz KL, Gronowicz GA, et al. Congenic mice provide in vivo evidence for a genetic locus that modulates serum insulin-like growth factor-I and bone acquisition. Endocrinology. 2006;147:3915–3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Motyl KJ, Bishop KA, DeMambro VE, et al. Altered thermogenesis and impaired bone remodeling in Misty mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:1885–1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bouxsein ML, Boyd SK, Christiansen BA, Guldberg RE, Jepsen KJ, Müller R. Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:1468–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lublinsky S, Ozcivici E, Judex S. An automated algorithm to detect the trabecular-cortical bone interface in microCT images. Calcif Tissue Int. 2007;81:285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Judex S, Luu YK, Ozcivici E, Adler B, Lublinsky S, Rubin CT. Quantification of adiposity in small rodents using micro-CT. Methods. 2010;50:14–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Motyl KJ, DeMambro VE, Barlow D, et al. Propranolol attenuates risperidone-induced trabecular bone loss in female mice. Endocrinology. 2015;156:2374–2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dempster DW, Compston JE, Drezner MK, et al. Standardized nomenclature, symbols, and units for bone histomorphometry: a 2012 update of the report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:2–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. DeMambro VE, Kawai M, Clemens TL, et al. A novel spontaneous mutation of Irs1 in mice results in hyperinsulinemia, reduced growth, low bone mass and impaired adipogenesis. J Endocrinol. 2010;204:241–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pack AI, Galante RJ, Maislin G, et al. Novel method for high-throughput phenotyping of sleep in mice. Physiol Genomics. 2007;28:232–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kaiyala KJ, Schwartz MW. Toward a more complete (and less controversial) understanding of energy expenditure and its role in obesity pathogenesis. Diabetes. 2011;60:17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Arch JR, Hislop D, Wang SJ, Speakman JR. Some mathematical and technical issues in the measurement and interpretation of open-circuit indirect calorimetry in small animals. Int J Obes (Lond). 2006;30:1322–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kaiyala KJ, Morton GJ, Leroux BG, Ogimoto K, Wisse B, Schwartz MW. Identification of body fat mass as a major determinant of metabolic rate in mice. Diabetes. 2010;59:1657–1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vernochet C, Mourier A, Bezy O, et al. Adipose-specific deletion of TFAM increases mitochondrial oxidation and protects mice against obesity and insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2012;16:765–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Xu J, Lloyd DJ, Hale C, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 reverses hepatic steatosis, increases energy expenditure, and improves insulin sensitivity in diet-induced obese mice. Diabetes. 2009;58:250–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Klok MD, Jakobsdottir S, Drent ML. The role of leptin and ghrelin in the regulation of food intake and body weight in humans: a review. Obes Rev. 2007;8:21–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Seale P. Transcriptional control of brown adipocyte development and thermogenesis. Int J Obes (Lond). 2010;34(suppl 1):S17–S22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Boström P, Wu J, Jedrychowski MP, et al. A PGC1-α-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesis. Nature. 2012;481:463–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cohen P, Levy JD, Zhang Y, et al. Ablation of PRDM16 and beige adipose causes metabolic dysfunction and a subcutaneous to visceral fat switch. Cell. 2014;156:304–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lidell ME, Seifert EL, Westergren R, et al. The adipocyte-expressed forkhead transcription factor Foxc2 regulates metabolism through altered mitochondrial function. Diabetes. 2011;60:427–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fisher FM, Kleiner S, Douris N, et al. FGF21 regulates PGC-1α and browning of white adipose tissues in adaptive thermogenesis. Genes Dev. 2012;26:271–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kawase T, Okuda K, Kogami H, et al. Characterization of human cultured periosteal sheets expressing bone-forming potential: in vitro and in vivo animal studies. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2009;3:218–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lee JH, Hwang KJ, Kim MY, et al. Human parathyroid hormone increases the mRNA expression of the IGF system and hematopoietic growth factors in osteoblasts, but does not influence expression in mesenchymal stem cells. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34:491–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hamidouche Z, Fromigue O, Ringe J, Haupl T, Marie PJ. Crosstalks between integrin α 5 and IGF2/IGFBP2 signalling trigger human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal osteogenic differentiation. BMC Cell Biol. 2010;11:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Thrailkill KM, Siddhanti SR, Fowlkes JL, Quarles LD. Differentiation of MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts is associated with temporal changes in the expression of IGF-I and IGFBPs. Bone. 1995;17:307–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hakeda Y, Yoshizawa K, Hurley M, et al. Stimulatory effect of a phorbol ester on expression of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) binding protein-2 and level of IGF-I receptors in mouse osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells. J Cell Physiol. 1994;158:444–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hurley MM, Abreu C, Hakeda Y. Basic fibroblast growth factor regulates IGF-I binding proteins in the clonal osteoblastic cell line MC3T3-E1. J Bone Miner Res. 1995;10:222–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Xi G, Wai C, DeMambro V, Rosen CJ, Clemmons DR. IGFBP-2 directly stimulates osteoblast differentiation. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:2427–2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nadal-Casellas A, Proenza AM, Lladó I, Gianotti M. Effects of ovariectomy and 17-β estradiol replacement on rat brown adipose tissue mitochondrial function. Steroids. 2011;76:1051–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Motyl KJ, Rosen CJ. The skeleton and the sympathetic nervous system: it's about time! J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:3908–3911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kajimura D, Hinoi E, Ferron M, et al. Genetic determination of the cellular basis of the sympathetic regulation of bone mass accrual. J Exp Med. 2011;208:841–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Elefteriou F, Campbell P, Ma Y. Control of bone remodeling by the peripheral sympathetic nervous system. Calcif Tissue Int. 2014;94:140–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kim JK, Kim HJ, Park SY, et al. Adipocyte-specific overexpression of FOXC2 prevents diet-induced increases in intramuscular fatty acyl CoA and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2005;54:1657–1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rahman S, Lu Y, Czernik PJ, Rosen CJ, Enerback S, Lecka-Czernik B. Inducible brown adipose tissue, or beige fat, is anabolic for the skeleton. Endocrinology. 2013;154:2687–2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Itoh N. FGF21 as a hepatokine, adipokine, and myokine in metabolism and diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2014;5:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Adams AC, Yang C, Coskun T, et al. The breadth of FGF21's metabolic actions are governed by FGFR1 in adipose tissue. Mol Metab. 2012;2:31–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ding X, Boney-Montoya J, Owen BM, et al. βKlotho is required for fibroblast growth factor 21 effects on growth and metabolism. Cell Metab. 2012;16:387–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Emanuelli B, Vienberg SG, Smyth G, et al. Interplay between FGF21 and insulin action in the liver regulates metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bornstein S, Brown SA, Le PT, et al. FGF-21 and skeletal remodeling during and after lactation in C57BL/6J mice. Endocrinology. 2014;155:3516–3526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wheatcroft SB, Kearney MT, Shah AM, et al. IGF-binding protein-2 protects against the development of obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56:285–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]