Abstract

The Obstetric Anaesthetists' Association and Difficult Airway Society have developed the first national obstetric guidelines for the safe management of difficult and failed tracheal intubation during general anaesthesia. They comprise four algorithms and two tables. A master algorithm provides an overview. Algorithm 1 gives a framework on how to optimise a safe general anaesthetic technique in the obstetric patient, and emphasises: planning and multidisciplinary communication; how to prevent the rapid oxygen desaturation seen in pregnant women by advocating nasal oxygenation and mask ventilation immediately after induction; limiting intubation attempts to two; and consideration of early release of cricoid pressure if difficulties are encountered. Algorithm 2 summarises the management after declaring failed tracheal intubation with clear decision points, and encourages early insertion of a (preferably second-generation) supraglottic airway device if appropriate. Algorithm 3 covers the management of the ‘can't intubate, can't oxygenate’ situation and emergency front-of-neck airway access, including the necessity for timely perimortem caesarean section if maternal oxygenation cannot be achieved. Table 1 gives a structure for assessing the individual factors relevant in the decision to awaken or proceed should intubation fail, which include: urgency related to maternal or fetal factors; seniority of the anaesthetist; obesity of the patient; surgical complexity; aspiration risk; potential difficulty with provision of alternative anaesthesia; and post-induction airway device and airway patency. This decision should be considered by the team in advance of performing a general anaesthetic to make a provisional plan should failed intubation occur. The table is also intended to be used as a teaching tool to facilitate discussion and learning regarding the complex nature of decision-making when faced with a failed intubation. Table 2 gives practical considerations of how to awaken or proceed with surgery. The background paper covers recommendations on drugs, new equipment, teaching and training.

-

What other guidelines are available on this topic?

The Difficult Airway Society UK (DAS) and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Task Force guidelines for the management of the difficult airway exclude obstetric patients [1,2]. The ASA Task Force's Practice Guidelines for Obstetric Anesthesia deal with equipment for the management of airway emergencies [3]. Recent national failed intubation guidelines from Canada [4,5] and Italy [6] have small sections on the obstetric patient. In the UK, many hospitals have developed their own obstetric failed intubation guidelines, often based on the DAS algorithm for use during rapid sequence induction of anaesthesia [7].

-

Why were these guidelines developed?

There are no national guidelines on the management of difficult airway in obstetrics in the UK. Non-obstetric guidelines do not address the problem that surgery is often being performed with extreme urgency to ensure the wellbeing of a different individual to the patient. These guidelines was developed to include specific measures accounting for the physiological and physical changes relating to the presence of a fetus that affect oxygenation and airway management, as well as to provide a structure for advance planning should failed intubation arise. There is a need for standardisation of the approach to obstetric failed intubation because there are declining numbers of general anaesthetics with consequent reduction in experience, especially among trainee anaesthetists [8].

-

How do these guidelines differ from existing ones?

These are the first national obstetric-specific failed intubation guidelines in the UK. The algorithms contain a minimal number of decision points. They include attention to advance planning, teamwork, and non-technical as well as technical skills and, in conjunction with a table, clarify the potentially conflicting priorities of the mother and the fetus. With careful attention to optimising general anaesthetic technique, it is hoped that airway difficulties can be minimised and advance plans be made in case of difficulties, accepting that these may need to be modified as events unfold.

-

Why do these guidelines differ from existing ones?

There is growing support for modernising the administration of general anaesthesia at caesarean section, and making it more consistent with non-obstetric practice. These guidelines acknowledge and conform with that trend.

Introduction

The rate of failed tracheal intubation in obstetrics has remained unchanged over the past four decades [9]. The first obstetric failed intubation guideline was published by Tunstall in 1976 [10]. Since then, there have been many local modifications to the original guideline as a result of developments in anaesthetic practice and changing patient population. Since the introduction of national guidelines for failed intubation in non-obstetric patients [1], a need for an equivalent for the obstetric patient has been identified [11]. This paper presents the resultant guidelines developed by the working group commissioned by the Obstetric Anaesthetists' Association (OAA) and the DAS.

Methods

The OAA/DAS Obstetric Anaesthetic Difficult Airway Guidelines Group was formed in May 2012 with representatives from both organisations. We initially performed a comprehensive review of the literature on failed tracheal intubation following rapid sequence induction of obstetric general anaesthesia [9]. Further workstreams included a national OAA survey of lead obstetric anaesthetists to clarify aspects of management of difficult and failed intubation [12], and a secondary analysis of neonatal outcomes from the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS) obstetric failed tracheal intubation database [9]. The draft algorithms and tables were presented at annual scientific meetings of both societies and were made available online for comments by members. Other stakeholders (Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (AAGBI), Royal College of Anaesthetists, British Association of Perinatal Medicine, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Royal College of Midwives) were also consulted.

Identification of evidence

A preliminary search of international guidelines and published literature was carried out. We performed a structured literature search of available scientific publications from 1950 to 2014 using databases (Medline, Embase, Pubmed, National Guidelines Clearinghouse), search engines (Google Scholar, Scirus), Cochrane database and officially recognised websites (DAS, OAA, Clinical Trials (see http://www.clinicaltrials.gov)). There were no language restrictions.

Abstracts were searched using keywords and filters. The words and phrases used were: intubation; difficult airway; obstetric; pregnancy; pregnant; pregnant woman; airway problem; cricothyroidotomy; laryngeal mask; LMA; supraglottic airway device; ProSeal LMA; LMA Supreme; i-gel; videolaryngoscope; Airtraq; Glidescope; MacGrath; C-Mac; Pentax airway scope; McCoy laryngoscope; airway assessment; Mallampati; thyromental distance; physiology of airway in pregnancy; failed intubation; cricoid pressure; cricothyroid; rapid sequence induction; general anaesthesia; pre-oxygenation; thiopentone; propofol; etomidate; suxamethonium; rocuronium; sugammadex; awake intubation; awake fibreoptic intubation; awake laryngoscopy; conscious laryngoscopy; and tracheostomy. The search was repeated monthly until June 2015. In total, 7153 abstracts were checked for relevance, following which 693 full papers were examined.

Classification of evidence

All scientific evidence was reviewed according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine 2011 levels of evidence criteria [13]. Apart from a handful of studies, the published literature comprised either case reports or series, observational studies, opinion pieces or reviews. There is a larger amount of non-obstetric literature on airway management, some of which can be extrapolated to the obstetric situation. In view of this, the Guidelines Group decided that it was necessary to produce guidelines based on expert consensus rather than high-level evidence.

Why is airway management more difficult in the obstetric patient?

Maternal, fetal, surgical and situational factors contribute to the increased incidence of failed intubation.

The mucosa of the upper respiratory tract becomes more vascular and oedematous, leading to increased risk of airway bleeding and swelling. These changes result in increasing Mallampati score as pregnancy progresses, and also during labour and delivery [14–18]. Swelling may be exacerbated by pre-eclampsia [19,20], oxytocin infusion, intravenous fluids and Valsalva manoeuvres during labour and delivery [15,16,21]. Decreased functional residual capacity and increased oxygen requirements accelerate the onset of desaturation during apnoea, and these are exacerbated in the obese parturient. Progesterone reduces lower oesophageal sphincter tone, resulting in gastric reflux, and a delay in gastric emptying occurs during painful labour and after opioid administration. Enlarged breasts may make the insertion of the laryngoscope difficult.

The majority of obstetric difficult and failed intubations occur during emergencies and out of hours [22,23]. Concerns for rapid delivery of the fetus often lead to time pressure, which may result in poor preparation, planning, communication and performance of technical tasks.

There has been a decline in the number of obstetric general anaesthetics performed in the developed world over the past three decades as regional anaesthesia has become more popular [23–26], resulting in reduced training opportunities [8,27]. Specific airway skills, including bag and mask ventilation and tracheal intubation, have declined with the increased use of supraglottic airway devices (SADs) [28]. Trainees may start obstetric on-call without having performed or observed a general anaesthetic in the obstetric patient [12]. Moreover, many obstetric units are remote from the main hospital site, delaying access to senior help and specialist equipment. Human factors play a significant role in decision-making, task management and communication during critical situations [29,30]. Fixation error has been highlighted as a specific concern during airway emergencies [31].

These guidelines mainly concern general anaesthesia for caesarean section. However, the physiological changes of pregnancy will also affect anaesthesia carried out for other procedures during pregnancy and the postpartum period, and therefore many principles are also relevant in such cases.

The OAA/DAS obstetric difficult and failed intubation guidelines

The guidelines comprise:

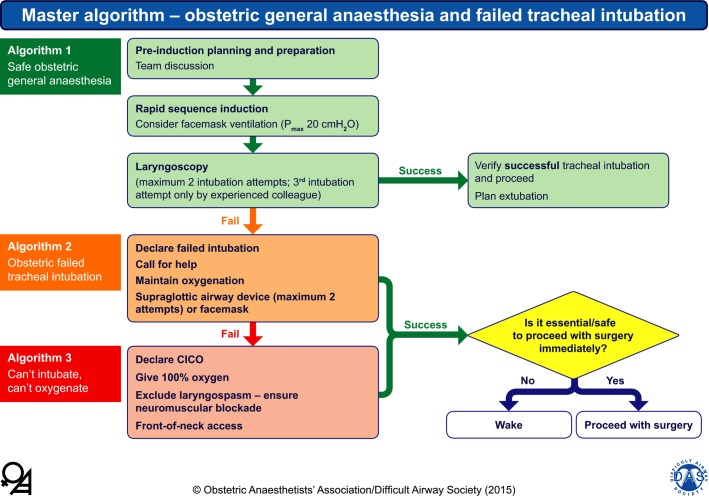

Master algorithm – obstetric general anaesthesia and failed tracheal intubation (Fig.1)

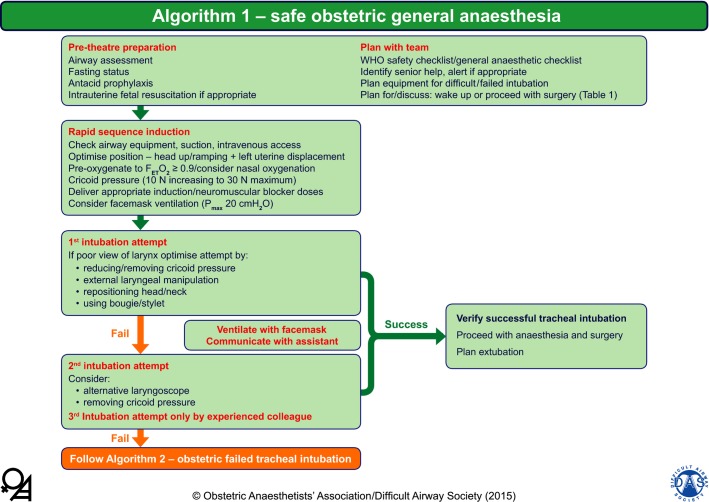

Algorithm 1 – safe obstetric general anaesthesia (Fig.2)

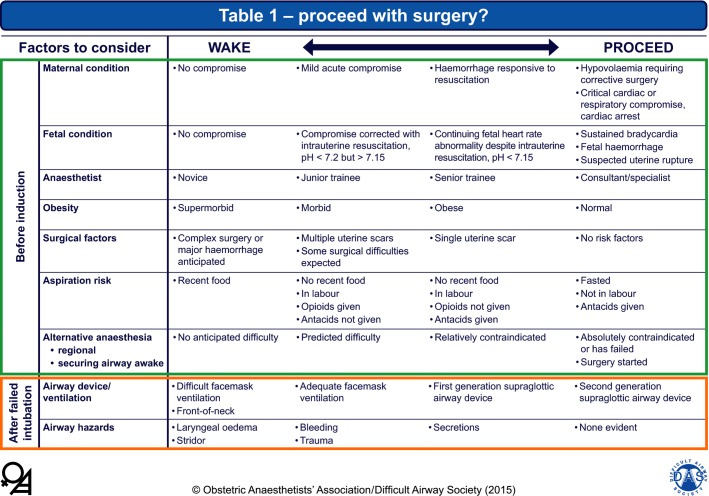

Table 1 – wake or proceed to surgery? (Fig.3)

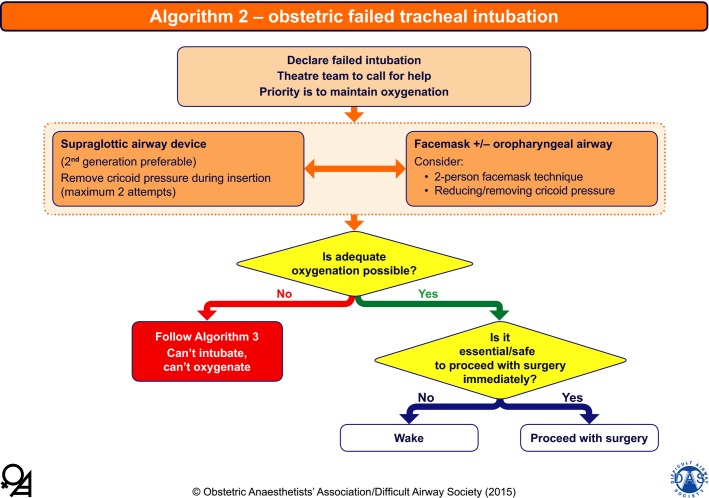

Algorithm 2 – obstetric failed tracheal intubation (Fig.4)

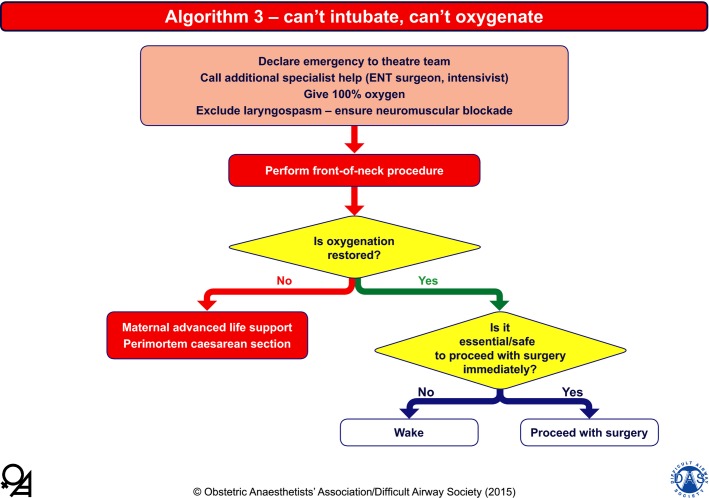

Algorithm 3 – can't intubate, can't oxygenate (Fig.5)

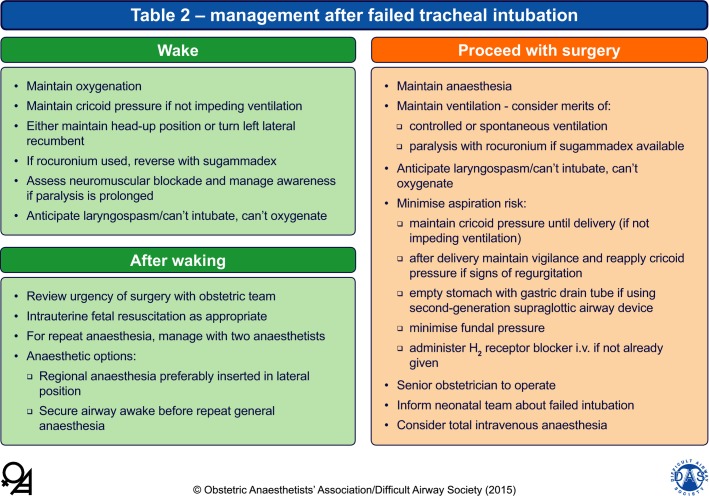

Table 2 – management after failed tracheal intubation (Fig.6)

Figure 1.

Master algorithm – obstetric general anaesthesia and failed intubation. The yellow diamond represents a decision-making step. Pmax, maximal inflation pressure; CICO, ‘can't intubate, can't oxygenate’. The algorithms and tables are reproduced with permission from the OAA and DAS and are available online in pdf and PowerPoint formats.

Figure 2.

Algorithm 1 – safe obstetric general anaesthesia. WHO, World Health Organization; FETO2, end-tidal fraction of oxygen; Pmax, maximal inflation pressure. The algorithms and tables are reproduced with permission from the OAA and DAS and are available online in pdf and PowerPoint formats.

Figure 3.

Table 1 – wake or proceed with surgery? Criteria to be used in the decision to wake or proceed following failed tracheal intubation. In any individual patient, some factors may suggest waking and others proceeding. The final decision will depend on the anaesthetist's clinical judgement. The algorithms and tables are reproduced with permission from the OAA and DAS and are available online in pdf and PowerPoint formats.

Figure 4.

Algorithm 2 – obstetric failed tracheal intubation. The yellow diamonds represent decision-making steps; the lower right decision step links to Table 1 (Fig.3). The boxes at the bottom link to Table 2 (Fig 6). The algorithms and tables are reproduced with permission from the OAA and DAS and are available online in pdf and PowerPoint formats.

Figure 5.

Algorithm 3 – ‘can't intubate, can't oxygenate’. The yellow diamonds represent decision-making steps; the lower right decision step links to Table 1 (Fig.3). The boxes at the bottom link to Table 2 (Fig. 6). ENT, ear, nose and throat. The algorithms and tables are reproduced with permission from the OAA and DAS and are available online in pdf and PowerPoint formats.

Figure 6.

Table 2 – management after failed tracheal intubation. i.v., intravenous. The algorithms and tables are reproduced with permission from the OAA and DAS and are available online in pdf and PowerPoint formats.

Master algorithm – obstetric general anaesthesia and failed tracheal intubation (Fig.1)

This is a composite of the three specific algorithms.

Algorithm 1 – safe obstetric general anaesthesia (Fig.2)

This emphasises the importance of planning and preparation, and describes best practice for rapid sequence induction and laryngoscopy. By understanding the physiological differences during pregnancy and employing best practice technique, it is hoped that airway problems can be anticipated and minimised.

Pre-theatre preparation

Airway assessment

Every woman undergoing obstetric surgery should have an airway assessment to predict possible difficulty not only with tracheal intubation but also with mask ventilation or SAD insertion and front-of-neck access. There are a number of common factors that are associated with difficulty in performing all of these airway management tasks (Appendix 1). The assessment should be documented clearly [22,32]. Oral piercings should be removed before any form of anaesthesia as they may cause trauma and bleeding during intubation as well as carrying the added risk of aspiration if pieces detach [33].

Women predicted to have significant airway difficulties, such that rapid sequence induction would not be suitable, should be referred antenatally for formulation of a specific anaesthetic and obstetric management plan.

Fasting status and antacid prophylaxis

Gastric clearance in the pregnant woman who is not in labour is the same as in the non-pregnant patient [34]. Labour and opioid analgesia delay gastric emptying, especially of food [35], but it returns to normal by 18 h post-delivery [36].

Current guidance for elective non-obstetric surgery suggests that food should be withheld for 6 h, whereas clear fluids may be given up to 2 h pre-operatively [37]. The commonest regimen for stomach preparation before elective caesarean section [38] is a combination of a H2-receptor antagonist the night before and two hours before anaesthesia, with or without a prokinetic drug. If general anaesthesia is being used, sodium citrate is also administered immediately before induction [38,39].

During labour, gastric emptying is slowed unpredictably and eating in labour increases residual gastric volume [35]. The recommended approach in the UK during labour is to stratify women into low- or high- risk for requiring general anaesthesia [40]. Low-risk women are allowed a light diet. High-risk women should not eat but may have clear oral fluids, preferably isotonic drinks, together with oral administration of H2-receptor antagonists every 6 h [40,41]. If anaesthesia is required for delivery, an H2-receptor antagonist should be given intravenously if not already administered, with the aim of reducing the risk of aspiration at extubation. Sodium citrate should be given as for elective cases [38,39].

Intrauterine fetal resuscitation

Intrauterine fetal resuscitation should be employed as appropriate before emergency operative delivery, and the urgency of surgery should be re-evaluated after transfer to the operating theatre [42].

Plan with team

The World Health Organization surgical checklist should be used before each theatre procedure [43]. This is often modified locally for caesarean section/operative vaginal delivery; in some units a specific anaesthetic checklist is used in addition [44]. The anaesthetist should be informed by the obstetrician about the clinical details of the case and the current urgency category. There should be a clear procedure for how to contact a second anaesthetist if required; if appropriate, induction of anaesthesia should be delayed while awaiting his/her attendance. Standardisation of airway equipment within the hospital is highly recommended [45]. The anaesthetic team should be familiar with the content of the airway trolleys and these should be regularly checked.

Table 1 – wake or proceed with surgery? (Fig.3)

Before induction of anaesthesia, the anaesthetist should discuss with the obstetric team whether to wake the woman or continue anaesthesia in the event of failed tracheal intubation. This decision is influenced by factors relating to the woman, fetus, staff and clinical situation, most of which are present pre-operatively (Table 1). The table highlights the many factors that need to be considered; the exact combination may be unique in each individual case. It is a useful exercise for the anaesthetist to consider at this stage whether (s)he would be prepared to provide anaesthesia for the duration of surgery with a SAD as the airway device.

Fetal compromise is a more common indication for urgent caesarean section than maternal compromise [46]. Although maternal safety is a greater priority for the anaesthetist than fetal, women willingly accept some risk to themselves to ensure a good neonatal outcome [46]. Fetal condition is likely to be maintained during a delay in the majority of cases [9]; at caesarean section for fetal bradycardia in one study, there was a significant decline in neonatal pH with increasing bradycardia-delivery interval only in cases with an irreversible cause for the bradycardia, in contrast to those with a potentially reversible or unascertained cause [47]. Irreversible causes include major placental abruption [48], fetal haemorrhage (e.g. from ruptured vasa praevia) [49], ruptured uterine scar with placental/fetal extrusion [50], umbilical cord prolapse with sustained bradycardia [51,52] and failed instrumental delivery [47]. Such specific causes for fetal distress may only become evident after delivery, and therefore a high index of suspicion is necessary. Potentially reversible causes include uterine hyperstimulation, hypotension after epidural anaesthesia/analgesia, and aortocaval compression [47].

The overriding indications to proceed with general anaesthesia are maternal compromise not responsive to resuscitation, and acute fetal compromise secondary to an irreversible cause as above (especially when an alternative of rapid spinal anaesthesia or awake intubation is not feasible). The firm indications to wake the mother up are periglottic airway swelling and continuing airway obstruction in the presence of optimised SAD or facemask management.

General anaesthesia is continued after failed intubation in most cases of elective as well as emergency caesarean section in current UK practice [9,12,22].

Rapid sequence induction

The theatre team should keep noise to a minimum during preparation and induction of anaesthesia to reduce distraction and to ensure that all staff remain aware of the developing situation.

Optimise patient position

Optimal positioning is essential before the first intubation attempt. In addition to lateral uterine displacement as indicated, the head-up position should be considered. A 20–30o head-up position increases functional residual capacity in pregnant women [53] and safe apnoea time in non-pregnant obese and non-obese patients [54–57]. It also decreases difficulty with insertion of the laryngoscope caused by large breasts, improves the view at laryngoscopy [58] and may reduce gastro-oesophageal reflux [59]. In the morbidly obese patient, the ‘ramped’ position, aligning the external auditory meatus with the supra-sternal notch, has been shown to be superior to the standard ‘sniffing position’ for direct laryngoscopy [60]. Certain hairstyles can affect neck extension and lead to difficulty with intubation. Elaborate hair braids may require removal before anaesthesia [61–65].

Pre-oxygenation

Pre-oxygenation increases the oxygen reserve in the lungs during apnoea. End-tidal oxygen fraction (FETO2) is the best marker of lung denitrogenation [66,67]; an FETO2 ≥ 0.9 is recommended [67,68]. Breath-by-breath oxygen monitoring can be used to monitor the process; this should be corroborated with a capnogram as erroneous values of FETO2 may be displayed because of apparatus deadspace and dilution from high fresh gas flows. A fresh gas flow rate of ≥ 10 l.min−1 is required for effective denitrogenation, and a tight mask-to-face seal is essential to reduce air entrainment [67]. Most anaesthetists pre-oxygenate for ≥ 3 min even during category-1 caesarean section [69]; however, previous clinical research and recent computer modelling shows that a 2-min period of pre-oxygenation is adequate for the term pregnant woman at term [66,70].

If the patient is apnoeic and the airway is not being instrumented, continued administration of 100% oxygen with a tightly fitting facemask and maintenance of a patent airway allows continued oxygenation by bulk flow to the alveoli (apnoeic oxygenation) [71]. In elective non-obstetric surgery, insufflation of oxygen via a nasopharyngeal catheter during laryngoscopy increases the time to desaturation in both normal and obese patients [72,73]. The anaesthetist should consider attaching nasal cannulae with 5 l.min−1 oxygen flow before starting pre-oxygenation, to maintain bulk flow of oxygen during intubation attempts [74,75]. New systems for nasal oxygenation that deliver humidified oxygen at high flow, such as the Optiflow™ system (Fisher and Paykel Healthcare Ltd, Panmure, Auckland, New Zealand), are being developed but these have only been assessed in non-pregnant patients [76].

Cricoid pressure

Cricoid pressure during rapid sequence induction has long been debated [77]. Cricoid pressure is used almost universally in the UK during general anaesthesia for caesarean section [78], although practice varies in other countries [79]. Current evidence supports applying 10 N force initially and then increasing to 30 N after loss of consciousness [80], as too much force (e.g. 44 N) is associated with airway obstruction [81,82]. If the head-up position is used for induction, this force can be reduced to 20 N [59]. Taylor et al. recently described a cricoid cartilage compression device that might improve standardisation of cricoid pressure [83].

The direction that cricoid pressure is applied should account for any lateral tilt of the operating table. Videolaryngoscopes provide a display on a screen from a camera at the tip of the blade; this allows the assistant to adjust cricoid pressure and improve the view of the glottis [84].

Incorrectly applied cricoid pressure can lead not only to a poor view at laryngoscopy but also to difficulties with insertion of the tracheal tube or SAD, mask ventilation and advancement of the tracheal tube over an introducer [82,85–88]. Because of these concerns, there should be a low threshold to reduce or remove cricoid pressure should intubation or mask ventilation prove difficult; it should be removed for insertion of a SAD. If cricoid pressure is reduced or removed, there is a possibility that regurgitation may occur; the anaesthetist and assistant should be ready to reapply cricoid pressure, administer oropharyngeal suction, introduce head-down tilt or a combination thereof.

Deliver appropriate doses of induction agent/neuromuscular blocking drug

Thiopental remains the most commonly used drug in UK for induction during rapid sequence induction in obstetrics [89–91]. However, the case for its continued use has greatly diminished; there are strong recommendations to use propofol instead for reasons that include familiarity, supply, ease of drawing up and fewer drug errors [90,92,93]. Propofol also suppresses airway reflexes more effectively than thiopental [94], which may be an advantage should intubation fail. The Fifth National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the AAGBI (NAP5) found a high incidence of awareness in obstetrics, and highlighted inappropriately low doses of thiopental (< 4 mg.kg−1) as one of the factors [95]. Hence, it is important to ensure that an adequate dose of induction agent is administered initially, and that further doses are available should difficulty with intubation be encountered.

Suxamethonium has been the standard neuromuscular blocking drug for rapid sequence induction as it had a faster onset and shorter duration than the alternatives. Although there is a presumption that its action will wear off to allow spontaneous ventilation in the event of failure to intubate, it has been shown that hypoxia occurs before recovery of neuromuscular activity [96,97]. A unique disadvantage is that suxamethonium increases oxygen consumption through its depolarising action, and hence may cause earlier desaturation than rocuronium [98].

The use of high-dose rocuronium (1.0–1.2 mg.kg−1) with sugammadex backup is a suitable alternative to suxamethonium, as rocuronium can be fully reversed by sugammadex (16 mg.kg−1) within 3 min compared with 9 min for the spontaneous offset of suxamethonium [99–103]. However, because of the time taken to prepare sugammadex, its use must be anticipated and the dose pre-calculated, and it should be immediately available for an assistant to draw up and administer [100]. The use of the rocuronium/sugammadex combination is currently limited because of the cost of sugammadex.

Consider facemask ventilation

Mask ventilation before laryngoscopy has generally been avoided during rapid sequence induction for fear of gastric insufflation and increasing the risk of regurgitation [104], but this should not occur with correctly applied cricoid pressure and using low peak ventilatory pressures [105,106]. Currently, gentle bag/facemask ventilation (maximal inflation pressure < 20 cmH2O) is recommended after administration of induction drugs during rapid sequence induction as it can reduce oxygen desaturation [104], and may allow an estimation of the likelihood of successful bag–facemask ventilation should it be required during prolonged or failed intubation attempts.

First intubation attempt

Anaesthetists must be familiar with the performance benefits and limitations of the laryngoscopes available on their airway trolley. A short-handled Macintosh laryngoscope has been the device of choice in the UK for tracheal intubation in pregnant patients. McCoy blades and obtuse angle devices (e.g. polio blade) are commonly stocked, although the latter are rarely used [12].

Videolaryngoscopes usually provide a better view of the glottis than direct laryngoscopes. There is extensive experience with their use in non-obstetric patients, including those with predicted difficult airways and following failed tracheal intubation [107–114], and it has been suggested that a videolaryngoscope should be the first-line device for all tracheal intubations [115].

A videolaryngoscope should be immediately available for all obstetric general anaesthetics. Currently, they are stocked in 90% of obstetric units in the UK [12]. In obstetric practice, videolaryngoscopes have been used at elective caesarean section, in morbidly obese patients and during failed intubation [116–125]. However, currently there are no comparative studies of the best videolaryngoscope for the obstetric population [126]. Despite a good glottic view, subsequent insertion of the tracheal tube may not be straightforward [127], and trauma has been described, particularly when using devices that require a stylet [128–131].

If a poor view of the larynx is obtained at the first laryngoscopy, attempts should be made to improve the view by reducing or removing cricoid pressure, external laryngeal manipulation and repositioning the head and neck [132,133]. Insertion of the tracheal tube can be facilitated with the use of a tracheal tube introducer (bougie) or a stylet. However, repeated attempts or blind passage of a bougie or tracheal tube carries a risk of airway trauma [45,134–136]. Small tracheal tubes (e.g. size 7.0) should be used routinely to improve the success rate and minimise trauma.

Second intubation attempt

If the first attempt at intubation fails, the second attempt should be by the most experienced anaesthetist present, using alternative equipment as appropriate. If delay is anticipated, we recommend that mask ventilation is recommenced during preparation. Cricoid pressure should be released as it may be the cause of the poor view; however, the view of the larynx may be improved by external laryngeal manipulation guided by the anaesthetist [133,137]. If there is a grade-3b or -4 view at laryngoscopy, the success rate of blind insertion of a bougie or tracheal tube is low and the risk of airway trauma is high, especially with multiple attempts; early abandonment of attempts at intubation is strongly recommended to avoid causing trauma and loss of control of the airway. A third attempt at intubation should only be by an experienced anaesthetist. Administration of a further dose of intravenous anaesthetic should be considered to prevent awareness [95].

Verify tracheal intubation

Deaths from oesophageal intubation still occur in the UK [45,138]. A sustained capnographic trace is the most reliable method of confirming tracheal intubation. Severe bronchospasm or a blocked tracheal tube may rarely cause absent ventilation with a flat capnograph trace in spite of a correctly placed tracheal tube [31,45,139]. However, if a flat trace is seen after intubation, the presumption must be that the tracheal tube is located in the oesophagus until proven otherwise.

Secondary methods of assessing correct tracheal tube position include seeing the tube positioned between the vocal cords using a direct laryngoscope or videolaryngoscope, auscultation in the axillae and over the epigastrium, the oesophageal detector device [140] and fibreoptic inspection to see the tracheal rings and carina [45]. New methods such as ultrasonic localisation are promising, but require further studies [141].

Algorithm 2 – obstetric failed tracheal intubation (Fig.4)

If the second intubation attempt is unsuccessful, a failed intubation must be declared to the theatre team who should call for further help from an experienced anaesthetist. Once a failed intubation has been declared, the focus is to maintain oxygenation via either a facemask or a SAD, and prevent aspiration and awareness. An oropharyngeal airway, a four-handed (two-person) technique and release of cricoid pressure should be used if facemask ventilation is difficult [142].

If facemask ventilation has been attempted and found to be difficult, or the pre-induction decision was to proceed with surgery (Table 1; Fig.3), immediate insertion of a SAD is the preferred choice before the induction agent and suxamethonium wear off. Use of a laryngoscope may aid SAD placement [143,144]. Studies have shown that cricoid pressure applied with standard 30-N force using the single-handed technique impede laryngeal mask placement and adequate lung ventilation [87,88]. This may be because cricoid pressure prevents the distal part of the laryngeal mask from occupying the hypopharynx [88]. We recommend that cricoid pressure should be released temporarily during insertion of a SAD.

A second-generation SAD with a gastric drain tube is recommended to allow the passage of a gastric tube and the ability to generate higher inflation pressures [45]. It is important that the device is positioned and fixed correctly to ensure that gastric contents are vented through the oesophageal port [145]. If the SAD has an inflatable cuff, this should be inflated to the minimal pressure required to achieve an airway seal, and never exceeding 60 cmH2O [146]. If the first SAD does not provide an effective airway, an alternative size or device should be considered. As with tracheal intubation, multiple attempts at SAD placement increase the risk of trauma [147], and hence we recommend a maximum of only two insertion attempts.

Algorithm 3 – ‘can't intubate, can't oxygenate’ (Fig.5)

A period of failed ventilation is not uncommonly reported after failed intubation, but is usually not sustained [9]. Persistent failure to ventilate despite optimal attempts using a SAD and/or facemask may be caused by intrinsic patient factors; however, laryngeal spasm and poor chest wall compliance are potentially modifiable and may be improved by ensuring full neuromuscular blockade. If suxamethonium was used at induction, then if available the rocuronium/sugammadex combination is preferred.

When a ‘can't intubate, can't oxygenate’ situation has been declared, specialist help such as ear, nose and throat surgeon and/or intensivist should be called.

Front-of-neck procedure

The recommendations for performing a front-of-neck procedure are changing continually with respect to equipment, technique and human factors. A small-bore cannula technique has a high failure rate, especially in obese patients [45]. A surgical airway provides a definitive airway and has a higher success rate [148]. Ultrasound of the neck may be a useful aid to locate the correct site for front-of-neck access, even as an emergency procedure [149]. We suggest that current DAS guidelines for emergency front-of-neck airway access in the non-obstetric patient are followed (see http://www.das.uk.com/guidelines/downloads.html).

If the front-of-neck procedure fails to restore oxygenation, a cardiac arrest protocol should be instituted, including caesarean delivery if there is an undelivered fetus of > 20 weeks' gestation [150].

Is it safe or essential to proceed with surgery immediately?

If adequate oxygenation is achieved by any method after failed intubation, the provisional decision to wake the patient or continue general anaesthesia and proceed with surgery should be reviewed, especially with regard to a possible change in severity of maternal or fetal compromise (Table 1; Fig.3). The airway device and the presence of airway obstruction must be considered; suboptimal airway control, airway oedema, stridor and airway bleeding indicate a potentially unstable situation that may deteriorate during surgery if anaesthesia is continued and will lead towards a decision to wake up.

Table 2 – management after failed tracheal intubation (Fig.6)

Wake

If the decision is made to wake the patient following a failed intubation, oxygenation needs to be maintained while avoiding regurgitation, vomiting or awareness. Early failed intubation guidelines called for the woman to be turned into the left lateral recumbent position with or without head-down tilt, whereas more recent guidelines usually suggest maintaining the supine position with lateral uterine displacement [7]. In the event of regurgitation or vomiting, the lateral head-down position ensures the least risk of aspiration. However, the left lateral head-down position presents problems such as difficulty with turning heavier women, poor facemask seal and unfamiliarity; therefore, the supine head-up position may be preferable if some of these factors apply. During awakening, there is a risk of laryngeal spasm and a ‘cant intubate, can't oxygenate’ situation; the anaesthetist should prepare for this with appropriate equipment, drugs and personnel. If there is persisting paralysis and the clinical situation allows it, administration of further anaesthetic agent to reduce the chance of awareness should be strongly considered. Rocuronium should be reversed with sugammadex if it is available.

Following waking, the urgency of delivery should be reviewed with the obstetrician. The preferred options are regional anaesthesia or securing the airway while awake followed by general anaesthesia. Further anaesthetic management will require the woman's cooperation, suggesting that this must wait until she is responsive to command [151]. The lateral position is usually preferable for siting regional anaesthesia, especially if the woman's conscious level is impaired. If regional anaesthesia is performed, a backup plan for high or failed block must be formulated.

Awake intubation will usually be via the oral route, as nasal intubation risks bleeding from the nose. After topical anaesthesia has been established, intubation can be performed with a fibrescope, videolaryngoscope [152,153] or direct laryngoscope as appropriate. Any accompanying sedation should be minimised.

Tracheostomy may be the preferred option if the initial management has demonstrated features indicating extreme difficulty or danger with tracheal intubation via the upper airway.

If the anaesthetic was being provided for operative delivery, the neonatologist should be informed about the failed intubation, as this is an independent predictor of neonatal intensive care unit admission [9].

Proceed with surgery

When the decision has been made to continue with general anaesthesia and surgery, key issues to consider are: choice of airway device and ventilation strategy; maintenance of anaesthesia; use of cricoid pressure; drainage of gastric contents; and plans to perform delayed tracheal intubation if required.

Hypoxaemia may occur from causes other than hypoventilation, and its presence is not an absolute indication to change the airway device if pulmonary ventilation is adequate. Furthermore, ventilation/perfusion mismatch and pulmonary compliance may improve after delivery at caesarean section, and urgency may therefore dictate temporarily accepting suboptimal conditions until delivery.

A decision to use spontaneous or controlled ventilation should be made on a case-by-case basis; controlled ventilation was used after failed intubation in two-thirds of cases in a UK survey [12]. Positive pressure ventilation may be achieved with or without using a neuromuscular blocking drug. Using a neuromuscular blocking drug has several advantages including prevention of laryngospasm, reduction in peak airway pressures and gastric insufflation, and facilitation of surgery by reducing abdominal muscular tone; its use must be monitored with a peripheral nerve stimulator. The surgery should be performed by the most experienced surgeon available, and only minimal fundal pressure should be used to assist delivery. The neonatal team should be informed about the failed intubation.

Effective cricoid pressure is unlikely to be sustained beyond 2–4 min [154]. However, cricoid pressure should ideally be maintained until after delivery, following which it may be cautiously released; a high vigilance for regurgitation should be maintained throughout surgery.

If a second-generation SAD with a drain tube has been used, the stomach contents should be suctioned at the proximal end of the drain tube if regurgitation is occurring, or via a gastric tube inserted through the drain tube at an appropriate time during the case.

After failed intubation, anaesthesia should initially be maintained with a volatile agent. A non-irritant agent such as sevoflurane is advisable. Total intravenous anaesthesia with propofol should be considered if there is any concern about poor uterine contraction after delivery, as it does not produce a decrease in uterine muscle tone.

Constant evaluation of airway patency, ventilation and oxygenation is required during the case. If delayed tracheal intubation or front-of-neck access is required, this must not be attempted without additional senior anaesthetic assistance. Intubation via a SAD must only be attempted using a technique familiar to the anaesthetist. This should involve placement under direct vision with a fibrescope to avoid airway trauma and oesophageal intubation [155]. If a definitive airway is required and tracheal intubation cannot be performed safely, a tracheostomy will be required.

Extubation of the trachea

Problems at the end of anaesthesia and postoperatively may relate to pulmonary aspiration secondary to regurgitation or vomiting, airway obstruction or hypoventilation [31,45,138,156,157]. The Fourth National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Difficult Airway Society (NAP4) [45] showed that almost 30% of all adverse events associated with anaesthesia occurred at the end of anaesthesia or during recovery. In a series of 1095 women having general anaesthesia for caesarean section, McDonnell et al. recorded regurgitation in four cases at intubation and five at extubation (one of these at both intubation and extubation) [157]. The key issues in safe extubation are planning and preparation; the options for re-intubation should be considered, including the immediate availability of appropriate staff, equipment and drugs [158]. In obstetric practice, tracheal extubation is usually only performed when the woman is awake, responsive to commands, maintaining oxygen saturation and generating a satisfactory tidal volume. In the past, patients who had a rapid sequence induction underwent extubation in the left lateral/head-down position. More recently, there has been a trend towards extubation in the head-up position, which is likely to aid airway patency, respiratory function and access to the airway, especially in the obese parturient [159].

If re-intubation might be difficult (e.g. laryngeal or tracheal oedema in patients with pre-eclampsia or after traumatic intubation) or there is a concern with oxygenation, supplementary airway evaluation by direct laryngoscopy, fibreoptic examination or confirmation of an audible leak around a tracheal tube with the cuff deflated may be required. Transfer to the intensive care unit for controlled ventilation and delayed extubation may be appropriate [20,158,160,161].

Debriefing and follow-up

Following an anticipated or unanticipated difficult airway, task debriefing is an important opportunity for the individual and team to reflect on their performance. Successful debriefing is achieved by identifying aspects of good performance, areas of improvement and suggestions of what could be done differently in the future [45,162,163].

It is good practice to perform a follow-up visit for all obstetric patients who have undergone general anaesthesia, but this is particularly important after a difficult or failed tracheal intubation. Minor injuries are common. Serious but rare morbidity includes trauma or perforation to the larynx, pharynx or oesophagus. Perforation, presenting with pyrexia, retrosternal pain and surgical emphysema, is associated with a high mortality; if suspected, urgent review by an ear, nose and throat specialist is recommended [164]. Awareness during anaesthesia is more frequent if intubation has been difficult, and direct enquiry should be made about this during the follow-up visit [95,165].

In cases where management of the patient's airway has been difficult, full documentation should be made about the ease of mask ventilation, grade of laryngoscopy, airway equipment or adjuncts used, complications and other information that may assist with decision-making during future anaesthetics. A proforma is often used (DAS alert form) [166] for a letter to the patient and her general practitioner; if failed intubation has occurred, the READ code1 SP2y3 should be included [167,168]. For complex cases, it is good practice to offer the patient a follow-up outpatient appointment with an anaesthetist.

Teaching

The majority of failed intubations in obstetrics occur out of hours and in the hands of trainee anaesthetists [12,22,23], and there is hence a need to maximise training opportunities. The Royal College of Anaesthetists recommends that all general anaesthetics for elective caesarean section in training institutions should be used for teaching [169]. Components of airway control may also be taught in other clinical (bariatric, rapid sequence induction) and non-clinical (manikin, wetlab [170], low-/high-fidelity simulation) environments. Boet et al. suggested that high-fidelity simulation training, along with practice and feedback, can be used to maintain complex procedural skills for at least one year [171].

There is a growing range of specialised airway devices, and expertise in their use may take a significant caseload to develop [172,173]. Anaesthetists should develop competence in the use of any advanced airway equipment that is stocked in their hospital. Training on airway equipment and management of failed intubation should include other professionals who assist the anaesthetist and recover patients [174].

Front-of-neck airway access is needed in only 1 in 60 failed intubations [9], but when done effectively and without delay, may be life-saving. Providing training in these techniques, especially surgical cricothyroidotomy, is difficult; the wetlab is more realistic than manikins for these skills. A large proportion of the management of such an extreme situation involves non-technical skills. These include leadership, decision-making, communication, teamworking and situational awareness. Clinical information from critical incidents may be used as a basis for multidisciplinary simulation teaching [175]. Table 1 may be used in simulations as well as case-based discussion to explore the interaction of factors involved in the decisions about continuing anaesthesia and airway control, or waking after failed intubation.

The use of checklists and cognitive aids can improve standardisation, teamwork and overall performance in operating theatres and during crisis situations [43,176–181], and several have been described for use in general [45,182] and obstetric anaesthesia [44,183,184].

Future directions and research

Anaesthetic departments should review all cases of obstetric failed tracheal intubation, in a multidisciplinary setting when relevant. There should be a mechanism for practitioners to report cases of failed intubation to a central national register, to share information on new equipment and techniques used during management. There is a wide and ever-increasing range of specialised airway equipment, with little evidence on comparative merits; selection should be based on ‘ADEPT’ guidance [185]. The use of rocuronium with sugammadex at induction of anaesthesia requires greater familiarity: further research into the recovery profile and return of airway patency with use of this combination during the management of failed intubation is desirable.

Conclusions

These guidelines cover the essential elements and steps for safe management of obstetric general anaesthesia, with the intention of minimising the incidence of failed tracheal intubation while ensuring optimal management should it occur. The algorithms use simple flow pathways with minimal decision points. Algorithm 1 incorporates items to check during the preparation, planning and delivering of anaesthesia, to supplement the World Health Organization checklists. Table 1 allows a more structured evaluation of the multiple pre- and post-induction factors salient to the decision whether to wake or proceed after failed intubation (Algorithm 2) or a front-of-neck procedure (Algorithm 3); the examples in the rows are illustrative and will assume different importance both for individual practice as well as unit-based approaches, and therefore an individual case might be managed differently by different anaesthetists. Besides a clinical tool, the table can act as a focus for case-based teaching. Table 2 formulates detailed management for both awakening and proceeding with surgery after failed intubation, an area that has not been described in detail previously. We hope that the publication of national guidelines will improve consistency of clinical practice, reduce adverse events and provide a structure for teaching and training in failed tracheal intubation in obstetrics.

Acknowledgments

We thank the DAS and OAA members who gave their feedback during the public consultation, Michelle White for her help with formatting the figures, and the librarians in Leicester, particularly Louise Hull and Sarah Sutton.

The authors have taken care to confirm the accuracy of information; however, medical knowledge changes rapidly. It is not intended that these guidelines represent a minimal standard of care during management of the difficult airway or failed intubation, nor should they substitute for good clinical judgement. The application of this information remains the responsibility and professional judgement of the anaesthetist.

The algorithms and tables are available in pdf and PowerPoint formats on the websites of the OAA (http://www.oaa-anaes.ac.uk/ui/content/content.aspx?id=179) and DAS (http://www.das.uk.com/guidelines/downloads.html) for download and use by readers subject to permission.

Appendix 1 Factors that predict problems with tracheal intubation, mask ventilation, insertion of a supraglottic airway device and front-of-neck airway access

| Tracheal intubation [186–191] | Facemask ventilation [188,192] | SAD insertion [193] | Front-of-neck airway access [45] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass index > 35 kg.m−2 | X | X | X | X |

| Neck circumference > 50 cm | X | X | X | X |

| Thyromental distance < 6 cm | X | X | X | |

| Cricoid pressure [81,87,82,88] | X | X | X | |

| Mallampati grade 3–4 | X | X | ||

| Fixed cervical spine flexion deformity | X | X | ||

| Dentition problems (poor dentition, buck teeth) | X | X | ||

| Miscellaneous factors (obstructive sleep apnoea, reduced lower jaw protrusion, airway oedema) | X | X | ||

| Mouth opening < 4 cm | X |

SAD, supraglottic airway device.

Footnotes

Standardised clinical terminology code for UK general practitioners.

Competing interests

The OAA and DAS provided financial support during the development of these guidelines. MK is an Editor of Anaesthesia and this manuscript has undergone an additional external review as a result.

References

- 1.Henderson JJ, Popat MT, Latto IP, Pearce AC. Difficult Airway Society guidelines for management of the unanticipated difficult intubation. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:675–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apfelbaum JL, Hagberg CA, Caplan RA, et al. Practice Guidelines for management of the difficult airway: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:251–70. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31827773b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Obstetric Anesthesia. Practice guidelines for obstetric anesthesia: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Obstetric Anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:843–63. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000264744.63275.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Law JA, Broemling N, Cooper RM, et al. The difficult airway with recommendations for management – Part 1 – Difficult tracheal intubation encountered in an unconscious/induced patient. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 2013;60:1089–118. doi: 10.1007/s12630-013-0019-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Law JA, Broemling N, Cooper RM, et al. The difficult airway with recommendations for management – Part 1– The anticipated difficult airway. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 2013;60:1119–38. doi: 10.1007/s12630-013-0020-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petrini F, Accorsi A, Adrario E, et al. Recommendations for airway control and difficult airway management. Minerva Anestesiologica. 2005;71:617–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Obstetric Anaesthetists' Association. Clinical Guidelines: failed intubation http://www.oaa-anaes.ac.uk/ui/content/content.aspx?id=179 (accessed 19/07/2015)

- 8.Searle RD, Lyons G. Vanishing experience in training for obstetric general anaesthesia: an observational study. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 2008;17:233–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinsella SM, Winton ALS, Mushambi MC, et al. Failed tracheal intubation during obstetric general anaesthesia: a literature review. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2015.06.008. June 30; doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2015.06.008. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tunstall ME. Failed intubation drill. Anaesthesia. 1976;31:850. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinsella SM. Anaesthetic deaths in the CMACE (Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries) Saving Mothers' lives report 2006-08. Anaesthesia. 2011;66:243–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swales H, Mushambi M, Winton A, et al. Management of failed intubation and difficult airways in UK obstetric units: an OAA survey. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 2014;23:S19. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. 2011. The Oxford 2011 Levels of Evidence http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653 (accessed 19/07/2015)

- 14.Pilkington S, Carli F, Dakin MJ, et al. Increase in Mallampati score during pregnancy. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1995;74:638–42. doi: 10.1093/bja/74.6.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kodali B-S, Chandrasekhar S, Bulich LN, Topulos GP, Datta S. Airway changes during labor and delivery. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:357–62. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31816452d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chassard D, Le Quang D. Mallampati score during pregnancy. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2012;108 S2:ii200. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bryssine B, Chassard D, Le Quang D. Neck ultrasonography and mallampati scores in pregnant patients. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2012;108 S2:ii200. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leboulanger N, Louvet N, Rigouzzo A, et al. Pregnancy is associated with a decrease in pharyngeal but not tracheal or laryngeal cross-sectional area: a pilot study using the acoustic reflection method. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 2014;23:35–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heller PJ, Scheider EP, Marx GF. Pharyngolaryngeal edema as a presenting symptom in preeclampsia. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1983;62:523–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Connor R, Thorburn J. Acute pharyngolaryngeal oedema in a pre-eclamptic parturient with systemic lupus erythematosus and a recent renal transplant. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 1993;2:53–5. doi: 10.1016/0959-289x(93)90032-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jouppila R, Jouppila P, Hollmen A. Laryngeal oedema as an obstetric anaesthesia complication: case reports. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 1980;24:97–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1980.tb01514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quinn AC, Milne D, Columb M, Gorton H, Knight M. Failed tracheal intubation in obstetric anaesthesia: 2 yr national case-control study in the UK. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2013;110:74–80. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawthorne L, Wilson R, Lyons G, Dresner M. Failed intubation revisited: 17-yr experience in a teaching maternity unit. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1996;76:680–4. doi: 10.1093/bja/76.5.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rahman K, Jenkins JG. Failed tracheal intubation in obstetrics: no more frequent but still managed badly. Anaesthesia. 2005;60:168–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.04069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson RV, Lyons GR, Wilson RC, Robinson APC. Training in obstetric general anaesthesia: a vanishing art? Anaesthesia. 2000;55:179–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2000.055002179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsen LC, Pitner R, Camann WR. General anesthesia for cesarean section at a tertiary care hospital 1990-1995: indications and implications. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 1998;7:147–52. doi: 10.1016/s0959-289x(98)80001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith NA, Tandel A, Morris RW. Changing patterns in endotracheal intubation for anaesthesia trainees: a retrospective analysis of 80,000 cases over 10 years. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. 2011;39:585–9. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1103900408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yarrow S, Hare J, Robinson KN. Recent trends in tracheal intubation: a retrospective analysis of 97 904 cases. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:1019–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.03361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bromiley M. Have you ever made a mistake? Bulletin of the Royal College of Anaesthetists. 2008;48:2442–5. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clinical Human Factors Group. 2015. What is human factors? http://chfg.org/what-is-human-factors (accessed 19/07/2015)

- 31.Knight M, Kenyon S, Brocklehurst P, Neilson J, Shakespeare J, Kurinczuk JJ on behalf of MBRRACE-UK. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers' Care – Lessons Learned to Inform Future Maternity Care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2009–12. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGuire B. Pre-operative airway assessment. In: Colvin JR, Peden C, editors. Raising the Standard: A Compendium of Audit Recipes for Continuous Quality Improvement in Anaesthesia. 3rd edn. London: Royal College of Anaesthetists; 2012. pp. 78–9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuczkowski KM, Benumof JL. Tongue piercing and obstetric anesthesia: is there cause for concern? Journal of Clinical Anesthesia. 2002;14:447–8. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(02)00376-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macfie AG, Magides AD, Richmond MN, Reilly CS. Gastric emptying in pregnancy. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1991;67:54–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/67.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scrutton MJL, Metcalfe GA, Lowy C, Seed PT, O'Sullivan G. Eating in labour. A randomised controlled trial assessing the risks and benefits. Anaesthesia. 1999;54:329–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1999.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whitehead EM, Smith M, Dean Y, O'Sullivan G. An evaluation of gastric emptying times in pregnancy and the puerperium. Anaesthesia. 1993;48:53–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1993.tb06793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Pre-operative Assessment and Patient Preparation. The Role of the Anaesthetist 2. London: AAGBI; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schneck H, Scheller M. Acid aspiration prophylaxis and caesarean section. Current Opinion in Anesthesiology. 2000;13:261–5. doi: 10.1097/00001503-200006000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paranjothy S, Griffiths JD, Broughton HK, Gyte GML, Brown HC, Thomas J. Interventions at caesarean section for reducing the risk of aspiration pneumonitis. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 2011;20:142–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Intrapartum care: care of healthy women and their babies during childbirth. CG190, 2014. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg55 (accessed 19/07/2015)

- 41.Calthorpe N, Lewis M. Acid aspiration prophylaxis in labour: a survey of UK obstetric units. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 2005;14:300–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thurlow JA, Kinsella SM. Intrauterine resuscitation: active management of fetal distress. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 2002;11:105–16. doi: 10.1054/ijoa.2001.0933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, et al. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360:491–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0810119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wittenberg MD, Vaughan DJA, Lucas DN. A novel airway checklist for obstetric general anaesthesia. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 2013;22:264–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Royal College of Anaesthetists and Difficult Airway Society. Fourth National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Difficult Airway Society (NAP4). Major complications of airway management in the UK. Report and findings, 2011. http://www.rcoa.ac.uk/nap4 (accessed 19/07/2015) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Thomas J, Paranjothy S. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Clinical Effectiveness Support Unit. National Sentinel Caesarean Section Audit Report. London: RCOG Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leung TY, Chung PW, Rogers MS, Sahota DS, Lao TT-H, Chung TKH. Urgent cesarean delivery for fetal bradycardia. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2009;114:1023–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181bc6e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kayani SI, Walkinshaw SA, Preston C. Pregnancy outcome in severe placental abruption. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2003;110:679–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmidt WA, Affleck JA, Jacobson S-L. Fatal fetal hemorrhage and placental pathology. Report of three cases and a new setting. Placenta. 2005;26:419–31. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bujold E, Francoeur D. Neonatal morbidity and decision-delivery interval in patients with uterine rupture. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 2005;27:671–3. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30542-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prabulos A-M, Philipson EH. Umbilical cord prolapse: is the time from diagnosis to delivery critical? Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 1998;43:129–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sangwan V, Nanda S, Sangwan M, Malik R, Yadav M. Cord complications: associated risk factors and perinatal outcome. Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2011;1:174–7. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hignett R, Fernando R, McGlennan A, et al. Does a 30o head-up position in term parturients increase functional residual capacity? Implications for general anaesthesia. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 2008;17:S5. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lane S, Saunders D, Schofield A, Padmanabhan R, Hildreth A, Laws D. A prospective randomised controlled trial comparing the efficacy of pre-oxygenation in the 20 degrees head-up vs supine position. Anaesthesia. 2005;60:1064–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramkumar V, Umesh G, Philip FA. Preoxygenation with 200 head-up tilt provides longer duration of non-hypoxic apnea than conventional preoxygenation in non-obese healthy adults. Journal of Anesthesia. 2011;25:189–94. doi: 10.1007/s00540-011-1098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Altermatt FR, Munoz HR, Delfino AE, Cortinez LI. Pre-oxygenation in the obese patient: effects of position on tolerance to apnoea. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2005;95:706–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dixon BJ, Dixon JB, Carden JR, et al. Preoxygenation is more effective in the 25 degrees head-up position than in the supine position in severely obese patients: a randomized controlled study. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:1110–5. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200506000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee BJ, Kang JM, Kim DO. Laryngeal exposure during laryngoscopy is better in the 25 degrees back-up position than in the supine position. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2007;99:581–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vanner R. Cricoid pressure. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 2009;18:103–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Collins JS, Lemmens HJ, Brodsky JB, Brock-Utne JG, Levitan RM. Laryngoscopy and morbid obesity: a comparison of the “sniff” and “ramped” positions. Obesity Surgery. 2004;14:1171–5. doi: 10.1381/0960892042386869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuczkowski KM, Benumof JL. Anaesthesia and hair fashion. Anaesthesia. 2001;56:799–800. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2001.02181-2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Famewo CE. Difficult intubation due to a patient's hair style. Anaesthesia. 1983;38:165–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1983.tb13946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chikungwa MT. Popular hair style-an anaesthetic nightmare. Anaesthesia. 2000;55:305–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2000.01359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cattano D, Cavallone L. Airway management and patient positioning: a clinical perspective. Anesthesiology News. 2011;8:17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ashley E, Marshall P. Problems with fashion. Anaesthesia. 2000;55:834. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2000.01629-45.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Russell GN, Smith CL, Snowdon SL, Bryson TH. Pre-oxygenation and the parturient patient. Anaesthesia. 1987;42:346–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1987.tb03972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Russell EC, Wrench I, Feast M, Mohammed F. Pre-oxygenation in pregnancy: the effect of fresh gas flow rates within a circle breathing system. Anaesthesia. 2008;63:833–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rassam S, Stacey M, Morris S. How do you preoxygenate your patient? International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 2005;14:79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Diacon MJ, Porter R, Wrench IJ. Pre-oxygenation for caesarean section under general anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2012;67:563. [Google Scholar]

- 70.McClelland SH, Bogod DG, Hardman JG. Pre-oxygenation in pregnancy: an investigation using physiological modelling. Anaesthesia. 2008;63:259–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hardman JG, Wills JS, Aitkenhead AR. Factors determining the onset and course of hypoxemia during apnea: an investigation using physiological modelling. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2000;90:619–24. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200003000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Baraka AS, Taha SK, Siddik-Sayyid SM, et al. Supplementation of pre-oxygenation in morbidly obese patients using nasopharyngeal oxygen insufflation. Anaesthesia. 2007;62:769–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Taha SK, Siddik-Sayyid SM, El-Khatib MF, Dagher CM, Hakki MA, Baraka AS. Nasopharyngeal oxygen insufflation following pre-oxygenation using the four deep breath technique. Anaesthesia. 2006;61:427–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2006.04610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ramachandran SK, Cosnowski A, Shanks A, Turner CR. Apneic oxygenation during prolonged laryngoscopy in obese patients: a randomized, controlled trial of nasal oxygen administration. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia. 2010;22:164–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Weingart SD, Levitan RM. Preoxygenation and prevention of desaturation during emergency airway management. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2012;59:165–75. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Patel A, Nouraei SAR. Transnasal Humidified Rapid-Insufflation Ventilatory Exchange (THRIVE): a physiological method of increasing apnoea time in patients with difficult airways. Anaesthesia. 2015;70:323–9. doi: 10.1111/anae.12923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.El-Orbany M, Connolly LA. Rapid sequence induction and intubation: current controversy. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2010;110:1318–25. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181d5ae47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thwaites AJ, Rice CP, Smith I. Rapid sequence induction: a questionnaire survey of its routine conduct and continued management during a failed intubation. Anaesthesia. 1999;54:376–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1999.00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Benhamou D, Bouaziz H, Chassard D, et al. Anaesthetic practices for scheduled caesarean delivery: a 2005 French national survey. European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 2009;26:694–700. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e328329b071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vanner RG, Pryle BJ. Regurgitation and oesophageal rupture with cricoid pressure: a cadaver study. Anaesthesia. 1992;47:732–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1992.tb03248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Palmer JHM, Ball DR. The effect of cricoid pressure on the cricoid cartilage and vocal cords: an endoscopic study in anaesthetised patients. Anaesthesia. 2000;55:263–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2000.01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hartsilver EL, Vanner RG. Airway obstruction with cricoid pressure. Anaesthesia. 2000;55:208–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2000.01205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Taylor RJ, Smurthwaite G, Mehmood I, Kitchen GB, Baker RD. A cricoid cartilage compression device for the accurate and reproducible application of cricoid pressure. Anaesthesia. 2015;70:18–25. doi: 10.1111/anae.12829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Loughnan TE, Gunasekera E, Tan TP. Improving the C-MAC video laryngoscopic view when applying cricoid pressure by allowing access of assistant to the video screen. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. 2012;40:128–30. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1204000114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Haslam N, Parker L, Duggan JE. Effect of cricoid pressure on the view at laryngoscopy. Anaesthesia. 2005;60:41–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.04010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.McNelis U, Syndercombe A, Harper I, Duggan J. The effect of cricoid pressure on intubation facilitated by the gum elastic bougie. Anaesthesia. 2007;62:456–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Brimacombe J, White A, Berry A. Effect of cricoid pressure on ease of insertion of the laryngeal mask airway. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1993;71:800–2. doi: 10.1093/bja/71.6.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Asai T, Barclay K, Power I, Vaughan RS. Cricoid pressure impedes placement of the laryngeal mask airway. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1995;74:521–5. doi: 10.1093/bja/74.5.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Koerber JP, Roberts GEW, Whitaker R, Thorpe CM. Variation in rapid sequence induction techniques: current practice in Wales. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:54–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stone JP, Fenner LB, Christmas TR. The preparation and storage of anaesthetic drugs for obstetric emergencies: a survey of UK practice. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 2009;18:242–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Murdoch H, Scrutton M, Laxton CH. Choice of anaesthetic agents for caesarean section: a UK survey of current practice. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 2013;22:31–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rucklidge M. Up-to-date or out-of-date: does thiopental have a future in obstetric general anaesthesia? International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 2013;22:175–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2013.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lucas DN, Yentis SM. Unsettled weather and the end for thiopental? Obstetric general anaesthesia after the NAP5 and MBRRACE-UK reports. Anaesthesia. 2015;70:375–9. doi: 10.1111/anae.13034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McKeating K, Bali IM, Dundee JW. The effects of thiopentone and propofol on upper airway integrity. Anaesthesia. 1988;43:638–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1988.tb04146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pandit JJ, Andrade J, Bogod DG, et al. 5th National Audit Project (NAP5) on accidental awareness during general anaesthesia: summary of main findings and risk factors. Anaesthesia. 2014;69:1089–101. doi: 10.1111/anae.12826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Farmery AD. Simulating hypoxia and modelling the airway. Anaesthesia. 2011;66 S2:11–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Benumof JL, Dagg R, Benumof R. Critical hemoglobin desaturation will occur before return to an unparalyzed state following 1 mg/kg intravenous succinylcholine. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:979–82. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199710000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tang L, Li S, Huang S, Ma H, Wang Z. Desaturation following rapid sequence induction using succinylcholine vs. rocuronium in overweight patients. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2011;55:203–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2010.02365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Abu-Halaweh SA, Massad IM, Abu-Ali HM, Badran IZ, Barazangi BA, Ramsay MA. Rapid sequence induction and intubation with 1 mg/kg rocuronium bromide in cesarean section, comparison with suxamethonium. Saudi Medical Journal. 2007;28:1393–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sorensen MK, Bretlau C, Gatke MR, Sorensen AM, Rasmussen LS. Rapid sequence induction and intubation with rocuronium-sugammadex compared with succinylcholine: a randomized trial. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2012;108:682–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fuchs-Buder T, Schmartz D. The never ending story or the search for a nondepolarising alternative to succinylcholine. European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 2013;30:583–4. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32836315c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Girard T. Pro: rocuronium should replace succinylcholine for rapid sequence induction. European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 2013;30:585–9. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e328363159a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Naguib M. Sugammadex: another milestone in clinical neuromuscular pharmacology. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2007;104:575–81. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000244594.63318.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Brown JP, Werrett GC. Bag-mask ventilation in rapid sequence induction. A survey of current practice among members of the UK Difficult Airway Society. European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 2015;32:446–8. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lawes EG, Campbell I, Mercer D. Inflation pressure, gastric insufflation and rapid sequence induction. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1987;59:315–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/59.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Petito SP, Russell WJ. The prevention of gastric inflation – a neglected benefit of cricoid pressure. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. 1988;16:139–43. doi: 10.1177/0310057X8801600202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Maharaj CH, Costello JF, Harte BH, Laffey JG. Evaluation of the Airtraq® and Macintosh laryngoscopes in patients at increased risk for difficult tracheal intubation. Anaesthesia. 2008;63:182–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Malin E, Montblanc J, Ynineb Y, Marret E, Bonnet F. Performance of the Airtraq™ laryngoscope after failed conventional tracheal intubation: a case series. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2009;53:858–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sun DA, Warriner CB, Parsons DG, Klein R, Umedaly HS, Moult M. The GlideScope® Video Laryngoscope: randomized clinical trial in 200 patients. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2005;94:381–4. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ndoko SK, Amathieu R, Tual L, et al. Tracheal intubation of morbidly obese patients: a randomized trial comparing performance of Macintosh and Airtraq™ laryngoscopes. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2008;100:263–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jungbauer A, Schumann M, Brunkhorst V, Borgers A, Groeben H. Expected difficult tracheal intubation: a prospective comparison of direct laryngoscopy and video laryngoscopy in 200 patients. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2009;102:546–50. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bathory I, Frascarolo P, Kern C, Schoettker P. Evaluation of the GlideScope® for tracheal intubation in patients with cervical spine immobilisation by a semi-rigid collar. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:1337–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.06075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Suzuki A, Toyama Y, Katsumi N, et al. The Pentax-AWS® rigid indirect videolaryngoscope: clinical assessment of performance in 320 cases. Anaesthesia. 2008;63:641–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Maharaj CH, Costello JF, McDonnell JG, Harte BH, Laffey JG. The Airtraq® as a rescue airway device following failed direct laryngoscopy: a case series. Anaesthesia. 2007;62:598–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zaouter C, Calderon J, Hemmerling TM. Videolaryngoscopy as a new standard of care. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2015;114:181–3. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Dhonneur G, Ndoko S, Amathieu R, el Housseini L, Poncelet C, Tual L. Tracheal intubation using the Airtraq® in morbid obese patients undergoing emergency cesarean delivery. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:629–30. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200703000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Riad W, Ansari T. Effect of cricoid pressure on the laryngoscopic view by Airtraq in elective caesarean section: a pilot study. European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 2009;26:981–2. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32832e9a32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Turkstra TP, Armstrong PM, Jones PM, Quach T. GlideScope® use in the obstetric patient. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 2010;19:123–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Shonfeld A, Gray K, Lucas N, et al. Video laryngoscopy in obstetric anesthesia. Journal of Obstetric Anaesthesia and Critical Care. 2012;2:53. [Google Scholar]