Abstract

BACKGROUND

Students are the heart of the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) model. Students are the recipients of programs and services to ensure that they are healthy, safe, engaged, supported, and challenged and also serve as partners in the implementation and dissemination of the WSCC model.

METHODS

A review of the number of students nationwide enjoying the 5 Whole Child tenets reveals severe deficiencies while a review of student-centered approaches, including student engagement and student voice, appears to be one way to remedy these deficiencies.

RESULTS

Research in both education and health reveals that giving students a voice and engaging students as partners benefits them by fostering development of skills, improvement in competence, and exertion of control over their lives while simultaneously improving outcomes for their peers and the entire school/organization.

CONCLUSIONS

Creating meaningful roles for students as allies, decision makers, planners, and consumers shows a commitment to prepare them for the challenges of today and the possibilities of tomorrow.

Keywords: student-centered; educational outcomes; health outcomes; youth-adult partnerships; youth empowerment; youth engagement; Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) model

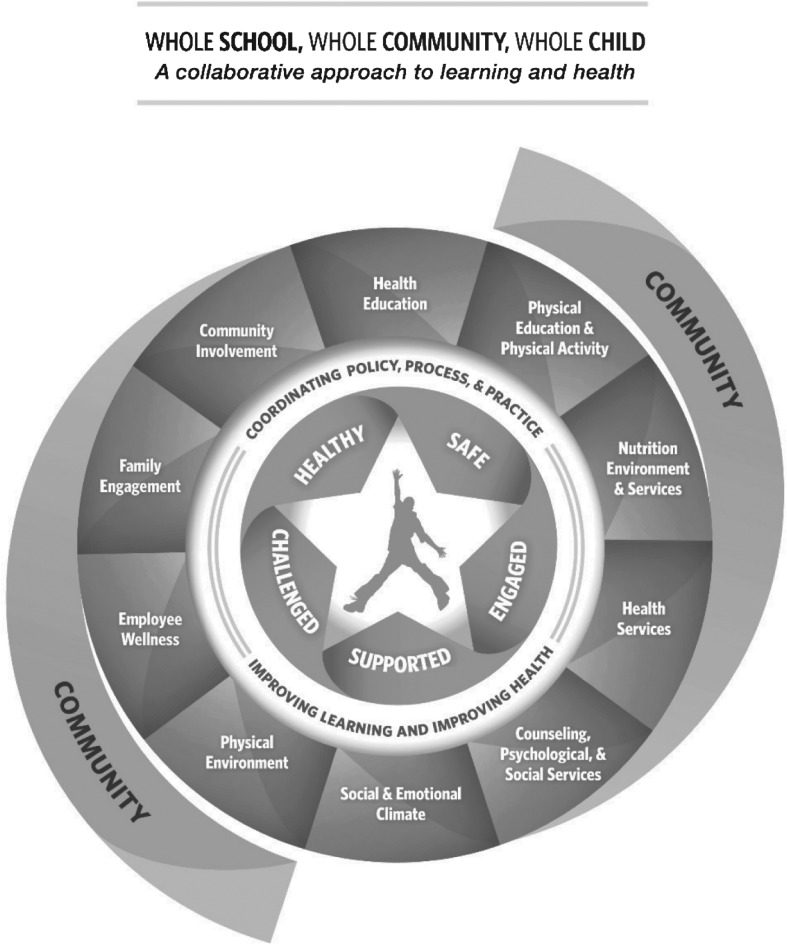

Most education reform efforts focus on curriculum, instruction, and assessment. This emphasis places responsibility for student success on school administrators and teachers. Little attention has been paid to the student—the consumer most impacted by educational policy and practice. The dissemination of the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) model,1 which combines and builds on elements of the traditional coordinated school health approach2 and the Whole Child Framework,3 provides the opportunity for emphasizing and promoting a student-centered approach in schools. The WSCC model places the 10 components of the coordinated school health model around the 5 Whole Child Tenets. The Whole Child Tenets are the intermediary, desired outcomes for every K-12 student. They contribute to academic achievement and ultimately a high-quality, healthy, productive life. The community envelopes the entire WSCC model, indicating that schools cannot accomplish these goals without community support. Peeling back these layers, students are at the very core of the model. The purpose of this article is to underscore that a student-centered model implies that students should be both recipients of services to ensure that they become healthy, safe, engaged, supported, and challenged and empowered as full partners in the implementation of the WSCC model.

Launched in 2007, the ASCD (formerly known as the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development) Whole Child Initiative helped move the educational conversation from a singular focus on academic achievement to one that promotes the long-term development and success of children by ensuring that all students have the fundamental resources they need to succeed. The updated WSCC approach combines a 10-component coordinated school health model with the original Whole Child Tenets, embedded in the WSCC model:

Each student enters school healthy and learns about and practices a healthy lifestyle.

Each student learns in an environment that is physically and emotionally safe for students and adults.

Each student is actively engaged in learning and is connected to the school and broader community.

Each student has access to personalized learning and is supported by qualified, caring adults.

Each student is challenged academically and prepared for success in college or further study and for employment and participation in a global environment.1

The WSCC model aims to change the way health and education intersect and support student health and achievement. By its very design, the model places the student at the core of this change. Rogers'4 research identified the variables needed for change to occur. This includes having individuals with authority and respect who articulate the needed changes (heterophily) as well as individuals that are similar (peers) voicing the need for a particular change (homophily). We believe that students can do so much more than just voice adult recommendations for change. Student-centered schools acknowledge the critical contributions students can and should make to their own learning and well-being. Students can become agents for change and allies for school improvement if schools create and nurture authentic relationships where students are perceived as essential, legitimate contributors to achieving their own health and academic success. Students can be the catalyst for change.

DISCUSSION

Educational reform leader Michael Fullan5( p170) observed that: “When adults do think of students, they think of them as the potential beneficiaries of change…they rarely think of students as participants in a process of school change and organizational life.” Fullan5 says that engaging the hearts and minds of students is the key to success in school but many schools see students only as sources of interesting and usable data. Students soon tire of invitations that address matters they do not think are important, use language they find restrictive, alienating, or patronizing and that rarely result in action or dialog that affects their lives. Despite demonstrated valuable and realistic ideas, student voice is not widespread and students are vastly underutilized resources. “Student engagement strategies must reach all students, those doing okay but bored by the irrelevance of school, and those who are disadvantaged and find schools increasingly alienating as they move through the grades.”5(p187)

The research on empowering students validates the wisdom of engaging youth in education, health, and social issues. Efficacy studies on youth peer mediation programs in which students are empowered to share responsibility for creating a safe and secure school environment demonstrated the value of turning to students as partners6,7 Students learned peer mediation skills, reduced suspensions and discipline referrals in schools, and improved the school climate.7 Research has also demonstrated that student peer educators achieve similar or better results than adult educators.8 A review article on the effects of giving students voice in the school decision-making process found evidence of moderate positive effects of student participation on life skills, democratic skills and citizenship, student-adult relationships, and school ethos while finding low evidence of negative effects.9 Wallerstein,10 who has supported the use of youth empowerment strategies in all aspects of health promotion, noted that student participation enhances self-awareness and social achievement, improves mental health and academic performance, and reduces rates of dropping out of school, delinquency, and substance abuse. A 2014 review of 26 articles11 to identify the effects of student participation in designing, planning, implementing, and/or evaluating school health promotion measures found conclusive evidence showing (1) enhanced personal effects on students (enhanced motivation, improved attitudes, skills, competencies, and knowledge); (2) improved school climate; and (3) improved interactions and social relationships in schools both among peers and between students and adults.

Both educational12,13 and health experts,10 as well as youth development experts,14 have advocated engaging students as partners to improve the health of peers, family, and community as well as improve the very process of school reform.5,12,13 Pittman et al noted that

Change happens fastest when youth and community development are seen as two sides of the same coin and young people are afforded the tools, training and trust to apply their creativity and energy to affect meaningful change in their own lives and in the future of their neighborhoods and communities.15(p6)

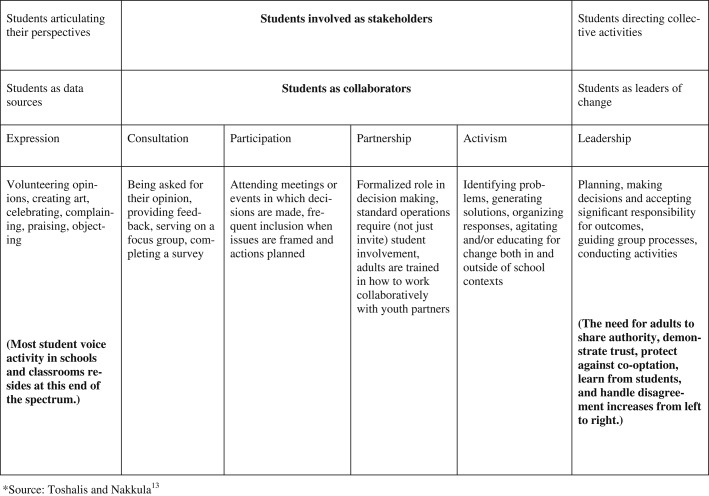

Toshalis and Nakkula13 support the effectiveness of students as partners in promoting change within the school. They noted that student voice most often is only at the far left of the spectrum, using students as data sources (Figure 1). However, in those schools that have tried involving students as leaders of change, remarkable success has occurred. Various forms of youth engagement such as peer education, peer mentoring, youth action, student voice, community service, service-learning, youth organizing, civic engagement, and youth-adult partnerships provide students with a sense of safety, belonging, and efficacy; gains in their sociopolitical awareness and civic competence; strengthened community connections;16 and improved achievement.14

Figure 1.

Spectrum of Student Voice in Schools and Community

Given the opportunity to discover their true passion, students will accept the challenge and deliver. High school student Zak Malamed17 and a few friends decided it was time for students to speak up. They held their first Twitter chat for students who were feeling frustrated about how little say they had in the school reform discussions going on around them. The question to students became “What can we do to improve this school?” from the impetus of several frustrated students to the organization known as Student Voice (http://www.studentvoice.org), the conversation has grown to a movement dedicated to revolutionizing education through the voices and actions of students. Supporters promise to advocate for students to be authentic partners in education and ensure that they have a genuine influence on decisions that affect their lives.

The Student Voice Collaboration18 was started by the New York City Department of Education to help students improve themselves and their schools. Participating students learned how the educational system works, interviewed school leaders about decision-making, and created a 1-page map showing how decisions were made in their school. Students conducted research on a challenge in their schools and then developed a student-led campaign to address the challenge. Finally, they set a city-wide agenda—identifying something that would benefit all New York City students. As a result of this work, one student group developed 6 recommendations that were shared with the New York City Chancellor of Education. The program's goal was to show students that they can bring about change by working within the system.

The Student-Centered Schools: Closing the Opportunity Gap evaluation study, conducted by the Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education,19 described how 4 student-centered high schools in California supported student success. Student-centered practices focused on the needs of students through a rigorous, rich, and relevant curriculum that connected to the world beyond school. Students engaged in activities that deepened learning and addressed their needs. Personalization was critical and students were provided with instructional supports that enabled success. Each of the 4 schools supported students' leadership capacities and autonomy through inquiry-based, student-directed, and collaborative learning within the classroom and in the community. Advisory programs, a culture of celebration, student voice, leadership opportunities, and connections to parents and community were embedded in each school. The study revealed that creating high schools designed around student rather than adult needs requires a shift in beliefs that must be translated into action.

The Stanford study19 also showed that teachers and administrators need to be prepared to address students' academic, social, and emotional needs in ways that empower students to take control of their own learning. This has significant implications for teacher and administrator preparation programs, teacher induction, and professional development. A culture of collaboration and partnership must go beyond traditional educator networks to include students as partners and consumers of educational programs and services. Meaningful student involvement requires educators to provide learning experiences that enhance students' skill development. Effective teachers guide students to discovery, help students make meaning of what they learn, and include students as essential and legitimate contributors to achieving their own health and success. Schools must continuously acknowledge the diversity of students by validating and authorizing them to represent their own ideas, opinions, knowledge, and experiences and truly become partners in every facet of school change but certainly in those programs and services that directly impact their health and well-being.

Student empowerment can and should begin in the elementary grades. Serriere et al20 described a youth-adult partnership in one elementary school in which mixed grade level K-5 students participated in Small School Gatherings described as social, civic, and academic networks designed to create a sense of community and encourage student voice. Group projects focused on “making a difference,” defined by the students as helping the poor, writing letters to military personnel, or aiding a local animal shelter. These authentic activities incorporated critical thinking, decision-making, collaboration, and planning skills and demonstrated that given the right circumstances, even the youngest students can have a voice in their work.

Similarly, the National Health Education Standards21 emphasize effective communication, goal setting, decision-making, and advocacy—all skills that enable students to take a more active role in their school and community. Ultimately, the goal is to prepare all students for college, career, and life, educating and empowering them to become informed, responsible, and active citizens.

The WSCC model provides a vehicle for students to create meaningful learning experiences in education and health that help create a safe and supportive school. Students can best articulate their own needs, thus maximizing the provision of health and counseling services. However, schools cannot simply ask a select few for their opinions or blessings; rather, schools must make concerted and genuine efforts to move from the contrived student voice of a few students to the meaningful student involvement of all students. “At the heart of meaningful student involvement are students whose voices have long been silenced.”12(p4)

Students' Perceptions of Achieving the 5 Whole Child Tenets

Every student deserves to be healthy, safe, engaged, supported, and challenged but evidence suggests that most students do not receive the supports they need to achieve these outcomes. While the Five Promises articulated by the America's Promise Alliance22 do not use the same terms as the WSCC model, they are quite similar in describing the fundamental needs of students: Healthy Start, Safe Places, Caring Adults (Supported), Opportunities to Help Others (Engaged), and, Effective Education (Challenged). A survey completed in 2006 by America's Promise revealed that 7 in 10 young people ages 12 to 17 (69%) received only 3 or less of the 5 fundamental resources needed to flourish. Only 31% (or 15·3 million students out of 49·4 million students) in grades 6-12 received 4 to 5 of these fundamental resources.

The 2014 Quaglia Institute for Student Aspirations' My Voice survey23 also confirmed the need for more resources. The survey, completed by a racially and socioeconomically diverse sample of 66,314 students in grades 6-12 representing 234 schools across the nation, was designed to measure variables affecting student academic motivation and concentrated on the following student constructs: self-worth, engagement, purpose/motivation along with peer support, and teacher support. The authors of the survey noted that the results of the 2014 survey demonstrated little change with the annual results since 2009. Students with a sense of self-worth were 5 times more likely to be academically motivated, yet 45% of students did not have a sense of self-worth. Those who described themselves as engaged were 16 times more likely to be academically motivated but 40% reported that they were not engaged. Students with a sense of purpose were 18 times more likely to be academically motivated but 15% reported no purpose. Teacher support increased academic motivation 8 times over while peer support increased academic motivation 4 times over. However, 39% of the students reported no teacher support and 56% reported no peer support.23

Clearly, there is a need for a more coordinated and collaborative approach to meeting students' basic needs—one involving families, schools, communities, and peers. The WSCC model could be one mechanism schools and communities use to improve students' feelings and experiences of self-worth, engagement, purpose, peer support, and teacher support as students become partners in the dissemination of the model.

How Schools Can Empower and Engage Students

Meaningful youth involvement in promoting the WSCC model needs to be promoted. Learning opportunities to empower youth can be divided into individual empowerment, organizational empowerment, and community empowerment.24 Individual empowerment occurs when youth develop the self-management skills, improve competence and exert control over their life, while organizational empowerment refers to schools and community organizations that provide opportunities for engaging in student empowerment as well as benefit from student empowerment. Community empowerment refers to the provision of opportunities for citizen participation at the local, state, and national level and the ensuing efforts to improve lives, organizations, and the community.25 Successful youth-adult partnerships happen when the relationships between youth and adults are characterized by mutuality in teaching, learning, and action. While these relationships usually occur within youth organizations or in democratic schools, they could become one mechanism for disseminating the WSCC model.

Fletcher asks adults to:

Imagine a school where democracy is more than a buzzword, and involvement is more than attendance. It is a place where all adults and students interact as co-learners and leaders, and where students are encouraged to speak out about their schools. Picture all adults actively valuing student engagement and empowerment, and all students actively striving to become more engaged and empowered. Envision school classrooms where teachers place the experiences of students at the center of learning, and education boardrooms where everyone can learn from students as partners in school change… [to improve not only education outcomes but also health outcomes].12(p4)

What can schools do to empower students and support student voice? The authors suggest adapting 4 goals identified by Fletcher,25 to include a health focus as well as a school improvement focus:

Engage all students at all grade levels and in all subjects as contributing stakeholders in teaching, learning, and leading in school [to ensure that student needs are being met].

Expand the common expectation of every student to become an active and equal partner in school change [that includes health-promoting student support programs and services as cornerstones of school improvement].

Provide students and educators with sustainable, responsive, and systemic approaches to engaging all students [in school improvement and health promotion] and

Validate the experience, perspectives, and knowledge of all students through sustainable, powerful, and purposeful school-oriented and school-community roles.25(pp7–8)

Table 1, an adaptation of a chart by Fletcher,12 provides examples of empowerment roles students can assume as partners in promoting achievement and health through the implementation of the WSCC model. While the table identifies opportunities at 3 grade clusters (E = elementary/K-5, M = middle grades/6-8, HS = high school/9-12), these suggestions can be easily adapted for any grade level.

Table 1.

Potential Roles for Students in the Implementation of the WSCC*

| Potential roles | Illustrious Student Skill-Building Areas | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Planners/Consultants | • Cooperative leadership skills • Project planning • Identifying issues in education and health • Communication skills • Time management • Setting priorities • Delegation | • Planning the school day calendar (E, M, HS) • Designing classroom seating and work areas (E, M, HS) • Co-designing lessons and/or curriculum (E, M, HS) • Membership on school health team (E, M, HS) • Membership on school improvement team (E, M, HS) • Student-created district budget (HS) • Serving on community boards (M, HS) • Serving on planning team for a student health center (M, HS) • Advising the local Board of Education on health-related policies (M, HS) • Planning school-wide health activities such as a health fair, fun run, or activity night (E, M, HS) |

| Educators | • Learning styles • Teaching skills • Evaluation methods • Classroom planning • Topic understanding • Facilitation and presentation skills • Evaluation skills • Content expertise • Adapting for differences • Using background knowledge • Assessing skills and knowledge | • Co-designing, delivering, and evaluating lesson plans (E, M) • Providing peer education on 6 health risk behaviors related to premature death and disease (E, M, HS) • Participating in student/adult co-teaching (M, HS) • Teaching lessons on local health and education issues (HS) • Presenting health-related issues to community leaders (E, M, HS) • Conducting workshops for parents on health and education issues (E, M, HS) • Creating and sharing online lessons for students in another school or country (E, M, HS) • Providing instructional information over social media and other school and community media opportunities such as black boards, white boards, bulletin boards, table tents, public address system, school and community newspapers (E, M, HS) |

| Researchers | • Research methods • Identifying issues in health and education • Assessing research results • Designing action projects • Communicating findings in various formats • Applications to real world • Cause and effect • Cost-benefit analysis • Representing data in meaningful ways for various audiences | • Conducting school psychological climate evaluations (E, M, HS) • Conducting classroom and school physical environment assessments (M, HS) • Conducting surveys of student health and safety behaviors (E, M, HS) • Conducting student-designed action research (M, HS) • Identifying local issues (eg, disparities, diversity, youth issues, and community needs) (HS) • Studying access to health care issues for adolescents and making recommendations to school and public health officials (M, HS) • Analyzing the student/adult relationships within the school (E, M, HS) • Analyzing data about new programs (eg, new health education program, school-based clinic services, absentee reduction programs, and new student orientation programs) (E, M, HS) • Identifying access to community services for various age groups and make recommendations (E, M, HS) |

| Organizers | • Creating petitions • Understanding school governance • Understanding democratic process • Group process skills • Collaboration skills • Relationship skills • Issues in governance • Public speaking • Using social media in positive ways to reach various audiences • Conducting needs assessments | • Establishing student-led signature-collecting campaigns promoting their interests (E, M, HS) • Promoting student-designed school improvement agenda (M, HS) • Organizing student-led education/health conferences (HS) • Organizing capstone projects targeting various groups (eg, fitness activities for senior citizens and early childhood nutrition projects) (E, M, HS) • Implementing an advocacy campaign using social media or convening a public meeting on an issue (M, HS) • Developing materials on a health issue to influence policy makers at the local, state, and national levels (E, M, HS) • Organizing community-based programs to reduce tobacco and alcohol access to underage youth (M, HS) |

| Evaluators | • Self-awareness • Critical thinking • Small group facilitation • Event planning • Cost-benefit analysis • Understanding quality vs. quantity • Writing summary reports | • Conducting evaluation of student-led parent-teacher conferences (E, M, HS) • Evaluating student-created school programs on local health and education issues (M, HS) • Conducting surveys and focus groups to determine if current health care services meet student and staff needs (E, M, HS) • Conducting evaluations of student-run activities (E, M, HS) • Evaluating school meal programs for nutrition, food waste, and/or using the cafeteria as a nutrition learning laboratory (E, M, HS) • Surveying students about access to safe places to play and making recommendations to local authorities (E, M, HS) • Conducting focus groups with students, parents, and school staff (M, HS) |

| Decision Makers/Leaders | • Creating consensus • Teambuilding • Conflict resolution • Community building • Issues in education and health • Triage and prioritizing • Cause and effect • Adapting for differences | • Establishing student-led classroom governance (E, M, HS) • Implementing school wide promotion of health behavior issues (E, M, HS) • Promoting school wide student initiatives to improve school climate (E, M, HS) • Serving on teacher and principal hiring committees (HS) • Developing and participating in a student-teacher team leadership training (M, HS) • Developing and participating in student advisory, peer mediation, service learning, or community service (M, HS) |

| Advocates/Activists | • Active listening • Problem solving • Communication skills • Issues in education and health • Group decision-making • Diversity awareness • Facilitation skills • Event planning • Public speaking • Writing for different audiences | • Organizing health and/or safety advocates to promote health, environment, and educational classroom/school changes (E, M, HS), as well as community change (M, HS) • Utilizing students to promote community service learning issues (M, HS) • Promoting community-linked health services or school-based health center (M, HS) • Implementing an advocacy campaign using social media (M, HS) • Convening a public meeting on education, health, or social issues (M, HS) • Creating and running special interest clubs that address health issues (E, M, HS) • Petitioning policy makers about school health issues (eg, start time, school foods, and access to recess) (E, M, HS) |

E, elementary school; M, middle school; HS, high school; WSCC, Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child.

Adapted from Fletcher.12

A number of researchers14–16 have provided guidelines and recommendations for schools and communities on how to begin this process by:

developing a local database of resources for youth development;14

asking community-based organizations (CBOs) to document and share with schools what they specifically accomplish related to learning outcomes14 to coordinate a scope and sequence of learning;14

developing curricula that integrates community resources for learning and teaching;14

providing youth with a supportive “home base” in which youth can work with dedicated and nurturing adults;15

creating youth-adult teams that are intentional about the long-term social changes to be achieved;15

balancing the need for short-term individual supports for youth with long-term goal of community change;15

recognizing and rewarding youth for their participation in youth organizations;14

providing professional development for educators to learn about the power of youth organizations to assist in providing youth with skills;14

advocating for a line item in the community budget to support youth as partners in improving the community and schools;14

providing multiple options for youth participation ensuring that youth receive the support to progressively take on more responsibility as they gain experience and skills;16

providing coaching and ongoing feedback to both youth and adults;14,15

establishing strategies to recruit and retain a diverse core of youth;15,16

providing organizational resources such as budget, staff training, and physical space aligned to support quality youth-adult partnership;16 and

providing adults and youth with opportunities to reflect and learn with same-age peers.16

In addition, Kania and Kramer26 identified 5 conditions needed for achieving collective impact on any issue (but particularly educational reform) that could be instructive for school-community partnerships that support youth engagement and empowerment. These include a common agenda, shared measurement systems, mutually reinforcing activities, continuous communication, and backbone support functions (such as convening partners, conducting needs assessments, developing a shared strategic plan for aligning efforts, selecting success metrics, and designing an evaluation). Hung et al27 in a review of the factors that facilitated the implementation of health-promoting schools which also engaged community agencies as partners in the process, identified the following effective and somewhat similar strategies: following a framework/guideline; obtaining committed support from the school staff, school board, management, health agencies, and other stakeholders; adopting a multidisciplinary, collaborative approach; establishing professional networks and relationships; and continuing training and education. Hung et al also noted that coordination was the key to promoting school-community partnerships and encouraged a 2-pronged approach: a top-down approach, a more effective initiating force to introduce and support the coordination role; and a bottom-up commitment, including the participation of parents and students, critical for sustaining an initiative.

Ten years of research,14 assessing the contributions of 120 community youth-based organizations in 34 cities across the nation, revealed that students working with CBOs, when compared to youth in general, were 26% more likely to report having received recognition for good grades. Almost 20% were more likely to rate their chances of graduating from high school as “very high,” 20% were more likely to rate the prospect of their going to college as “very high,” and more than 2-1/2 times were more likely to think it is “very important” to do community service or to volunteer and give back to their community.14

Students can also play an important role within their own school or district. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention28 recommends that schools and communities establish school health coordinating councils at the community level to facilitate the communication and common goals recommended by Kania and Kramer as well as the professional networks and relationships identified by Hung et al as drivers of quality school health programs. District school health councils collaborate and coordinate with school-level teams. Members of both the district level and school councils/teams include representatives from education, public health, health and social service agencies, community leadership, and families. Some schools and districts have found that including students as critical contributors to the work of the councils/teams is vital.

The Center Consolidated School District (Colorado),29 recognizing the importance of a collaborative approach to student health and learning, has a Health Advisory Committee that represents the WSCC components and includes community professionals, school staff, parents, and students. The district believes that, with support, students can achieve academically and be successful in life. Health and wellness efforts are integrated into the work of the Center School District as reflected by a health and wellness goal for the district's Unified Improvement Plan. “The district sees wellness as the foundation for learning… sustained by creating and maintaining environments, comprehensive health, policies, practices, access to services and resources, and attitudes that develop and support the inter-related dimensions of physical, mental, emotional, and social health.”29 Persons at the district's Skoglund Middle School believe that “Educating students about leading a healthy lifestyle is important—and because students educate others about a healthy lifestyle and its impact, sustainability is enhanced. As administrators, staff, parents and students understand the importance of coordinated school health efforts, they become the school's strongest advocates.”30(p2) Skoglund has discovered that when parents and students demand something, it continues.30(p2) Clearly, student voice and involvement is valued in the district which uses the WSCC model to guide its work. Table 2 provides examples of resources to assist school and community agency staff members to empower students as partners, enable student voice, and develop students as partners for change.

Table 2.

Sample Resources for Student Empowerment and Voice

| Source | Description | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Act for Youth Center of Excellence | Publications, e-news, and presentations on youth-adult partnerships and youth development | http://www.actforyouth.net/youth_development/engagement/partnerships.cfm |

| Education Commission of the States | Articles and materials for student voice in service learning | http://www.ecs.org/html/projectspartners/nclc/SOS/nclc_SOSresources-studentvoice.htm |

| The Freechild Project | The Freechild Project, an international effort to foster social change led by and with young people connects young people and adults to the tools, training, and technical assistance they need to create new roles for youth | http://freechild.org/ |

| 4-H Clubs | • Youth-Adult Partnerships in Community Decision-Making publication, http://4h.ucanr.edu/files/2427.pdf • Youth development programs focused on leadership development and community action • Health and safety initiatives | http://www.4-h.org/ |

| The Forum for Youth Investment | • Workshops and trainings • Publications and guides • Focused on whole child, whole community approach to collective impact and continuous improvement • Research on youth services, youth development and community change | http://forumfyi.org |

| Student Voice | • Student Voice in a Box toolkit • Podcasts, videos, blogs, and classroom demonstrations | http://www.stuvoice.org |

| Soundout: Promoting Student Voice | SoundOut works with K-12 schools, districts, state and provincial education agencies, and non-profit education to promote Student Voice and student involvement in education. Provides research, resource, and leadership guides for youth alliances, service learning and student voice projects | http://www.soundout.org/ |

| Southern Poverty Law Center | • Provides an inventory to help teachers reflect on how student voice and input are integrated into schools and classrooms • Blog posts on student voice • Lesson plans on social justice, activism, and respect • Students as teachers | http://www.tolerance.org/magazine/number-46-spring-2014/feature/i-start-year-nothing |

| Youth Empowered Solutions | • Provides customized training and consulting to help adults, youth and organizations further their mission of engaging youth • Using a 3-pronged approach, their model engages youth in work that challenges them to develop skills, gain critical awareness, and participate in opportunities necessary for creating community change | http://www.youthempoweredsolutions.org/ |

IMPLICATIONS FOR SCHOOL HEALTH

The WSCC model places students in the center for a reason: students are the consumers of the programs and services we, the adults, provide. A student-centered school considers the thoughts and opinions of the students it serves. That means schools must seek out the opinions and ideas of every student, not just those elected to student government or acknowledged as school leaders. This dialogue must begin in elementary grades as students learn how to develop and present a convincing argument and advocate for their own health, safety, engagement, support for learning and academic challenges as well as these supports for their peers. These skills can be developed, refined, and supported by the implementation of a comprehensive, sequential PreK-12 health education program aligned with the National Health Education Standards.

School administrators must regularly engage all students through social media, surveys, town hall meetings, and focus groups. Creating a continuous feedback loop, where comments are welcomed and expected, is critical to supporting student voice. Whereas having student representatives on the school health committee/team is important, asking all students to participate in developing and implementing school health policies is necessary in order to create a safe environment for discussion. It is critical that students become involved in the conversation at the outset and not after decisions have already been made. Building trust in the “system” is crucial to the success of the WSCC model. As schools implement the WSCC approach, they must create an ongoing dialog about school health policies, programs and services and ensure that the student body is well-represented in those conversations. Three simple questions are critical to that process: What do students think about the planned policy, program or service? How will the policies, programs, and services impact all students in the school? What would the students do differently if given the opportunity to do so?

Ensuring that all students have the skills needed to become effective communicators is but a first step toward creating an environment where students feel safe and supported. Empowering students as partners in the dissemination of the WSCC model will help generate trust and acceptance and ensure that students' needs are being met. ASCD's The Learning Compact Redefined: A Call to Action set the stage for the development of the WSCC model with this statement: “We are calling for a simple change that will have radical implications: put the child at the center of decision-making and allocate resources—time, space, and human—to ensure each child's success.”3(p19) Creating meaningful roles for students as allies, decision makers, planners, and foremost, as consumers, ensures that our focus is truly student-centered. Placing students in the center of the WSCC model makes visible the commitment of education and health to collaboratively prepare today's students for the challenges of today and the possibilities of tomorrow. We can accomplish this by engaging and empowering students and acknowledging them as capable and valuable partners in the process (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) Framework. Source: ASCD1

Human Subjects Approval Statement

The preparation of this paper involved no original research with human subjects.

REFERENCES

- 1.ASCD; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child: A Collaborative Approach to Learning and Health. ASCD: Alexandria, VA; 2014. Available at: http://www.ascd.org/ASCD/pdf/siteASCD/publications/wholechild/wscc-a-collaborative-approach.pdf. Accessed December 10, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Components of coordinated school health. 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/cshp/components.htm. Accessed January 25, 2015.

- 3.ASCD. The Learning Compact Redefined: A Call to Action. A Report of the Commission on the Whole Child. Alexandria, VA: ASCD; 2007. p. 19. Available at: http://www.ascd.org/ASCD/pdf/Whole%20Child/WCC%20Learning%20Compact.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 4th ed. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fullan M. The New Meaning of Educational Change. 4th ed. New York, NY: Teachers College Press; 2007. pp. 170–187. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayorga MG. The effectiveness of peer mediation on student to student conflict. Perspect Peer Progr. 2010;22(2):3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris RD. Unlocking the learning potential in peer mediation: an evaluation of peer mediator modeling and disputant learning. Conflict Resol Q. 2005;23(2):141–146. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mellanby AR, Rees JB, Tripp JH. Peer-led and adult-led school health education: a critical review of available comparative research. Health Educ Res. 2000;15(5):533–545. doi: 10.1093/her/15.5.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mager U, Nowak P. Effects of student participation in decision making at school. A systematic review and synthesis of empirical research. Educ Res Rev. 2012;7(1):38–61. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wallerstein N. What is the Evidence on Effectiveness of Empowerment to Improve Health? Health Evidence Network Report. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe, Health Evidence Network; 2006. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/Document/E88086.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griebler U, Rojatz D, Simovska V, Forster R. Effects of student participation in school health promotion: a systematic review. Health Promotion Int. 2014 doi: 10.1093/heapro/dat090. [E-pub ahead of print]. Available at: http://heapro.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2014/01/05/heapro.dat090.full.pdf. Accessed January 6, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fletcher A. Meaningful Student Involvement: Guide to Students as Partners in School Change. 2nd ed. Olympia, WA: The Freechild Project; 2005. p. 4. Available at: http://www.soundout.org/MSIGuide.pdf. Accessed January 5, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toshalis E, Nakkula MJ. Motivation, Engagement, and Student Voice. The Students at the Center Series. Washington DC: Jobs for the Future; 2012. Available at: http://www.studentsatthecenter.org/topics/motivation-engagement-and-student-voice. Accessed January 25, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLaughlin MW. Community Counts: How Youth Organizations Matter for Youth Development. Washington, DC: Public Education Network; 2000. Available at: http://www.issuelab.org/resource/community_counts_how_youth_organizations_matter_for_youth_development. Accessed January 10, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pittman K, Martin S, Williams A. Core Principles for Engaging Young People in Community Change. Washington, DC: The Forum for Youth Investment, Impact Strategies, Inc; 2007. p. 15. Available at: http://forumfyi.org/files/FINALYouth_Engagment_8.15pdf.pdf. Accessed January 25, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeldin S, Petrokubi J, Camino L. Youth-Adult Partnerships in Public Action: Principles, Organizational Culture and Outcomes. Washington, DC: The Forum for Youth Investment; 2008. Available at: http://forumfyi.org/files/YouthAdultPartnerships.pdf. Accessed January 25, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korbey H. How can students have more say in school decisions. Available at: http://blogs.kqed.org/mindshift/2014/10/how-can-students-have-more-say-in-school-decisions/. Accessed December 15, 2014.

- 18. Student Voice Collaborative (SVC). About us. 2013. Available at: http://www.studentvoicecollaborative.com/about-us.html. Accessed January 20, 2015.

- 19.Daring-Hammond L, Friedlaender D, Snyder J. Student-Centered Schools: Policy Supports for Closing the Opportunity Gap. Stanford, CA: Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education; 2014. Available at: https://edpolicy.stanford.edu/projects/633. Accessed December 15, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Serriere SC, Mitra D, Reed K. Student voice in the elementary years: fostering youth-adult partnerships in elementary service-learning. Theor Res Soc Educ. 2011;39(4):541–575. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joint Committee on National Health Education Standards. National Health Education Standards: Achieving Excellence. 2nd ed. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2007. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/Healthyyouth/SHER/standards/index.htm. Accessed January 10, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22.America's Promise Alliance. Every Child, Every Promise: Turning Failure Into Action. Washington DC: America's Promise Alliance; 2006. Available at: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED505358.pdf. Accessed January 25, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quaglia Institute for Student Aspirations. My Voice National Student Report (Grades 6-12) 2014. Portland, ME: Quaglia Institute for Student Aspirations; 2014. Available at: http://www.qisa.org/dmsStage/My_Voice_2013-2014_National_Report_8_25. Accessed January 5, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ledford MK, Lucas B, Dairaghi J, Ravelli P. Youth Empowerment: The Theory and Its Implementation. Youth Empowered Solutions: Raleigh, NC; 2013. Available at: http://www.youthempoweredsolutions.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Youth_Empowerment_The_Theory_and_Its_Implementation_YES-11-13-13.pdf. Accessed January 20, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fletcher A. Stories of Meaningful Student Involvement. Olympia, WA: The Freechild Project; 2004. pp. 7–8. Available at: http://soundout.org/MSIStories.pdf. Accessed January 7, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kania J, Kramer M. Collective impact. Stanford Social Innov Rev. 2011;97:36–41. Available at http://www.ssireview.org/articles/entry/collective_impact. Accessed January 15, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hung TTM, Chiang VCL, Dawson A, Lee RLT. Understanding of factors that enable health promoters in implementing health-promoting schools: a systematic review and narrative synthesis of qualitative evidence. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e108284. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108284. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108284. Available at: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0108284#pone.0108284-Kolbe1. Accessed January 21, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). How schools can implement coordinated school health. 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/cshp/schools.htm. Accessed January 25, 2015.

- 29. Center Consolidated School District 26JT. Why school health? Available at: http://centerschoolshealthandwellness.weebly.com/why-school-health.html. Accessed January 25, 2015.

- 30. Healthy Schools Champions Magazine. 2014. Available at: http://www.coloradoedinitiative.org/resources/2014-healthy-school-champions/. Accessed January 25, 2015.