Abstract

BACKGROUND

The Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) model calls for greater collaboration across the community, school, and health sectors to meet the needs and support the full potential of each child. This article reports on how 3 states and 2 local school districts have implemented aspects of the WSCC model through collaboration, leadership and policy creation, alignment, and implementation.

METHODS

We searched state health and education department websites, local school district websites, state legislative databases, and sources of peer-reviewed and gray literature to identify materials demonstrating adoption and implementation of coordinated school health, the WSCC model, and associated policies and practices in identified states and districts. We conducted informal interviews in each state and district to reinforce the document review.

RESULTS

States and local school districts have been able to strategically increase collaboration, integration, and alignment of health and education through the adoption and implementation of policy and practice supporting the WSCC model. Successful utilization of the WSCC model has led to substantial positive changes in school health environments, policies, and practices.

CONCLUSIONS

Collaboration among health and education sectors to integrate and align services may lead to improved efficiencies and better health and education outcomes for students.

Keywords: school health; school education policy; school health policy; Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child Model; integrating health and education

A small body of research has demonstrated the critical links that exist between health and education, highlighting the importance of health to educational outcomes, and the importance of educational attainment to health.1–6 Despite these strong connections however, the health and education sectors have, for the most part, grown, developed, and established their influence independent of each other. Yet, they are often serving the same child, in the same location, often attending separately to similar issues.

The alignment, integration, and collaboration across health and education sectors hold the potential for greater efficiency, reduced resource consumption, and improved outcomes for both sectors. However, alignment, collaboration, and integration between 2 of the sectors that are of primary importance to children—education and health—can be a challenge. Local school districts often do not have a working relationship with their local health districts, rarely share information and data, and develop interventions without cross-sector collaboration and partnerships. At the state level, health and education departments can struggle to reach beyond their respective agencies, successfully manipulate funding streams and navigate authority structures to actively collaborate and align initiatives. Policymakers also miss opportunities to integrate health into state and local education policy and practice, and vice versa, as health and education have distinct accountability measures, and pressures to achieve short-term gains can make it challenging to take a more integrated, long-term approach.7

Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child Model

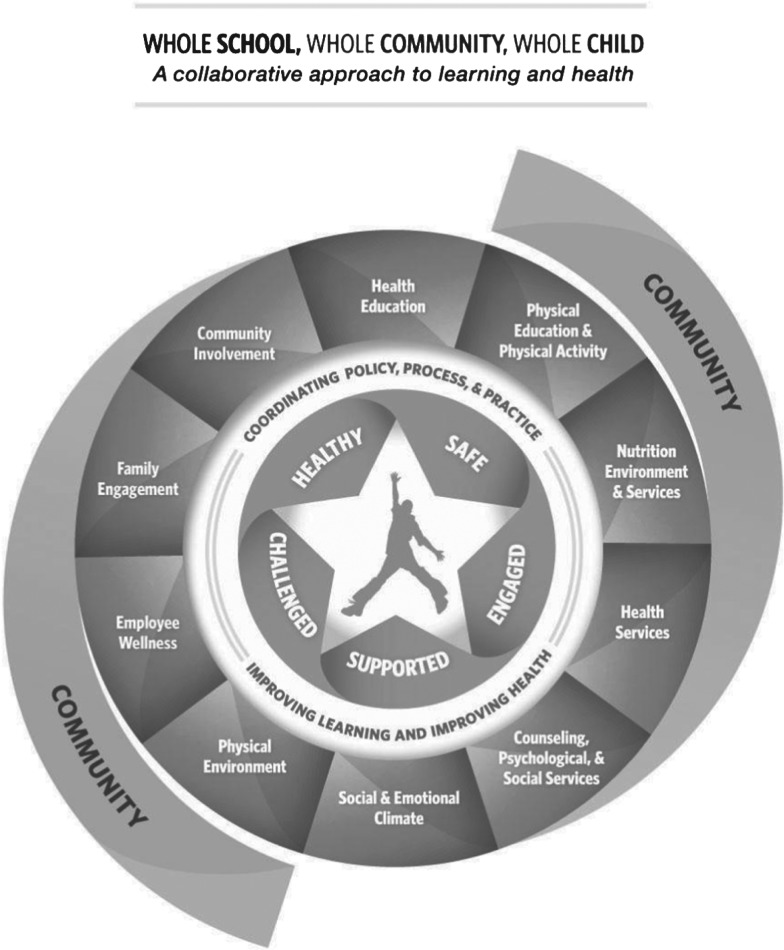

The Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) model (Figure 1), developed by ASCD (formerly the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development) and the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC), provides a framework and a call for the health and education sectors to work toward greater alignment and coordination of policy, process, and practice. The WSCC model, released in 2014, was developed to ensure that school-community and education-health sector alignments are front and center. The model expands the traditional 8-component coordinated school health (CSH) approach and deliberately places it inside the larger community in order to emphasize this connection and role. This includes not only an increase in the number of school health components from 8 to 10 but also the alignment of an education focus with a health focus. The new model calls for a greater collaboration across the community, school, and health and education sectors to meet the needs and support the full potential of each child.8

Figure 1.

Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) Model.

The benefits of collaboration, alignment, and integration between health and education can best be viewed in 3 key areas: leveraging resources, utilizing resources efficiently, and improving both health and education outcomes. A 2010 report from the Coalition of Community Schools cited 5 key ways that schools can efficiently leverage resources.9 This includes collaborative efforts to strengthen the core instructional mission of schools, leveraging community-wide financial resources, developing collaborative leadership structures and ownership, enhancing public/private partnerships, and providing coordination between and across systems. In terms of more efficient utilization, increased integration of health and education can improve usage of facilities and resources. Leveraging resources from across the community, as illustrated in the WSCC model, can aid both the establishment of school-community connections and health and educational outcomes. Examples include shared use agreements that can lead to improved community access to facilities for physical activity10,11 and school-based health centers that have been shown to reduce a community's inappropriate emergency room use, increase use of primary care, and result in fewer hospitalizations among regular users.12–14 Finally, strengthening the integration and collaboration between health and education benefits both sectors because research suggests that educational attainment is important to achieving better health outcomes,15,16 and health is key to better educational outcomes.2,3

Operationalizing WSCC requires moving from theoretical model to practical implementation through the development of state and local school policies and practices. Although the model is new, a number of states and local school districts have made significant strides over the last few years in their efforts to better align health and education by building a collaborative, integrated approach. Arkansas, Kentucky, Colorado, Maine Regional School Unit #22, and Denver Public Schools (DPS) all provide valuable examples of states and local districts that embraced WSCC's core vision of aligning health and education through the adoption of integrated policies and initiatives. Their trailblazing efforts demonstrate both the feasibility of implementing the WSCC model and the visionary leadership required to do so.

METHODS

We conducted a search of the health and education department's websites in Arkansas, Colorado, and Kentucky, and the school districts' websites in Maine Regional School Unit #22, and DPS for materials demonstrating adoption and implementation of CSH and its respective components or the WSCC model. We also conducted a search of the respective state legislative databases, state health and education department websites, and local school district websites for adopted policy relevant to CSH and the WSCC model. We searched PubMed, Web of Science, and Academic Search Premier and for relevant peer-reviewed articles around the implementation of aspects of CSH or WSCC in the 4 states and 2 local school districts. In addition, we searched online for news articles and gray literature highlighting the implementation of CSH or the WSCC model, or aspects of them, in each state and local school district.

Secondarily, we conducted informal reinforcing interviews via phone with 1 person in a key school health leadership role related to the promotion and implementation of the WSCC model in each district and state: Arkansas, Kentucky, and Colorado, Maine Regional School Unit #22 and DPS. The interviews were conducted between September and December 2014. The interviews were recorded and transcribed.

RESULTS

Applying the WSCC Model at the State Level

Arkansas

In Arkansas, the state health and education departments have a long history of working collaboratively and with partners to improve the health of students. The 2 agencies have jointly operated the Coordinated School Health Program (CSHP) for over 2 decades, working together to expand CSH in school districts across the state. They have been supported by a series of state laws that have created a strong and long-lasting foundation for their actions.

In 2003, the Arkansas legislature adopted Act 1220, landmark legislation addressing multiple areas of a healthy school environment.17 The legislation included requirements for body mass index (BMI) screening in schools; the establishment of a state-level Child Health Advisory Committee (CHAC) to develop rules and regulations for school nutrition, physical education (PE), and physical activity, and to make recommendations to the Arkansas State Board of Education and Board of Health; and the establishment of a wellness committee in each local school district. Act 1220 also created positions for regional community health promotion specialists (CHPS) specifically to assist schools and led to new standards for competitive foods and physical activity in schools, created by the Arkansas CHAC. Act 201 followed in 2007 to make modifications to the BMI screening and grade level requirements, provide a parental opt-out clause, and require the Department of Health to assign regional community health nurse specialists (CHNS) to work with schools to ensure appropriate protocols and follow up. Act 317 (2007) later strengthened the CHAC recommended physical activity requirements and required a half credit of PE for high school graduation.18

In 2009, Act 180 (Tobacco Excise Tax) made possible a state-level Joint Use Agreement Grant program collaboratively run by the Arkansas Department of Education (ADE), the Arkansas Department of Health (ADH), and the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement.19 The program assists schools in the adoption and implementation of shared use policies and the formation of collaborative community partnerships to increase opportunities for physical activity. Act 180 also provided funding for an annual School-Based Health Center Grant, a collaboration among ADE, ADH, the Arkansas Department of Human Services, and Medicaid in the Schools. This funding led to the establishment of 22 school-based health centers across the state, providing on-site clinical services for students and connecting them with community partners in an effort to meet their needs better.

Together, the impact of these laws has been considerable. To date, post-implementation data indicate that Act 1220 and the related policies have resulted in substantial positive changes in school health environments, policies, and practices, with widespread parental support and no increase in negative consequences such as weight-based teasing.20–22 Among the changes are improved nutrition environments in school districts across the state, including reduced access to less healthy competitive foods and beverages and increased access to healthier options, and stronger policies to promote physical activity and recess.20,21,23–27 The CHPS, employed by the State Health Department but housed in regional educational cooperatives, have worked together with CHNS to support local school districts, including assisting with the creation of wellness committees and policies, administering the School Health Index, and developing strategies to improve nutrition, physical activity, and health environment policies and programs. The state health and education departments have worked collaboratively, with initiatives guided by a School Health Services Team comprised of staff from various areas in each agency, including school health services, human immunodeficiency virus infection/acquired immune deficiency syndrome, mental health, Arkansas Medicaid in the Schools, the state school nurse consultant, Act 1220, and CSH. Team members provide ongoing support, training, and professional development to school districts throughout the state and to the CHPS and CHNS on topics such as wellness policies and administration of the School Health Index.

Kentucky

Kentucky provides another valuable example of a state that has worked to integrate health and education through the alignment of policy at the state level. Kentucky's state health and education departments have enjoyed a strong, collaborative relationship in recent years. Together, staff from each agency have worked together to increase awareness of CSH among education leaders across the state, including superintendents, principals, and school board members. They have collaborated with state associations including the Kentucky Association of School Councils, Kentucky School Nutrition Association, Kentucky Family Resource Youth Service Centers, and Kentucky Association of Health, Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance to promote understanding, adoption, and implementation of CSH at the local level. The state agencies have focused on helping education leaders make the connection between the CSH components and educational outcomes of academic achievement, discipline, and attendance. This foundation, along with strong relationships with state-level organizations including the Kentucky School Boards Association and the Kentucky Superintendents Association, has facilitated the adoption of education policies that support healthier schools and students.

An example of this can be seen in Kentucky's Program Review process. In 2009, the Kentucky legislature adopted Senate Bill 1, which established Program Review as a part of a new assessment and accountability model.28 In addition to ensuring district and school accountability for student achievement, the annual program reviews are designed to both audit and provide feedback and recommendations focused on improving the quality of educational experiences available to students. The Program Review includes a Practical Living/Career Studies component, encompassing health education and PE. The state health and education departments worked collaboratively to draft the Program Review rubric for the Practical Living/Career Studies component, setting a high baseline to support and strengthen the integration of health into school-level policies and practices.

Schools receive one of 4 designations during the Program Review process: No Implementation, Needs Improvement, Proficient, and Distinguished. To achieve the Proficient level for health education in the Practical Living/Career Studies Program Review, a school must have a CSH committee that is used as a support and resource for collaboration and integration of Health Education instruction in the school environment (Table 1). Similarly, to achieve Proficient in the Practical Living/Administrative Leadership/Support and Monitoring component, a school must convene its CSH committee at least twice a year, implement the district-level wellness policy via a school-level wellness policy reviewed annually, and include goals for school wellness in the Comprehensive School Improvement Plan (CSIP). For PE, the CSH committee of a Proficient school must utilize a Comprehensive School Physical Activity program (CSPAP) to increase quality PE and physical activity opportunities, and integrate the PE curriculum, providing opportunities for cross-disciplinary connections (Table 1). Whereas schools may go beyond these standards to achieve the Distinguished level, setting high requirements for the Proficient level has greatly incentivized the establishment of Coordinated School Health Committees in schools across the state, creation of school-level wellness policies, integration of wellness goals into the school improvement plans, and expansion of CSPAP. Using a common sense approach, Kentucky has intentionally and thoughtfully woven health into education measures, and in doing so, has taken a major step toward ensuring better integration of health and education at the local level.

Table 1.

Examples From Kentucky Practical Living/Career Studies (PLCS) Program Review Rubric*

| No Implementation | Needs Improvement | Proficient | Distinguished |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curriculum and Instruction Demonstrator 1. Health Education Students Have Equitable Access to High Quality, Rigorous Health Education Curriculum | |||

| To what extent does the school ensure a Coordinated School Heath Committee is used as a support and resource for collaboration and integration of health education instruction throughout the school environment? | |||

| There is no Coordinated School Health Committee. | A Coordinated School Health committee is in place but is not used to inform instructional practices. | A Coordinated School Heath Committee is used as a support and resource for collaboration and integration of health education instruction throughout the school environment. | A Coordinated School Health committee annually collects and analyzes data to create/review the school wellness policy and utilizes the policy to guide collaboration and integration of health education instruction throughout the school environment. |

| Curriculum and Instruction Demonstrator 2. Physical Education Students Have Equitable Access to High Quality, Rigorous Physical Education Curriculum | |||

| To what extent does the school ensure a Coordinated School Heath Committee is used as a support and resource for collaboration and integration of health education instruction throughout the school environment? | |||

| There is no Coordinated School Health Committee. | A Coordinated School Health committee is in place but is not used to inform instructional practices and/or increase physical activity opportunities within the school environment. | A Coordinated School Health committee utilizes a Comprehensive School Physical Activity Program (CSPAP) to increase the quality of the physical education instruction as well as increase physical activity opportunities throughout the school environment. | A Coordinated School Health committee annually collects and analyzes data to create/review the school wellness policy, including all components of CSPAP in the policy, to increase the quality of the physical education instruction as well as specific time allocated daily for physical activity opportunities throughout the school environment. |

| To what extent does the school ensure the physical education curriculum is integrated and includes regular opportunities for cross-disciplinary connections to meet the physical activity needs of all students? | |||

| There is no integration of the physical education curriculum. | School has limited integration opportunities of the physical education curriculum. | School ensures the physical education curriculum is integrated and includes regular opportunities for cross-disciplinary connections to meet the physical activity needs of all students. | School ensures the physical education curriculum is frequently integrated into all content areas to meet the physical activity needs of all students |

| Administrative/Leadership Support and Monitoring Demonstrator 1: Policies and Monitoring School Leadership Establishes and Monitors Implementation of Policies, Provides Adequate Resources, Facilities, Space, and Instructional Time to Support Highly Effective PLCS Instructional Programs | |||

| To what extent does school leadership ensure that Committees (Coordinated School Health committees, Career and Technical Education [CTE] program advisory committees) meet a minimum of twice per school year to ensure quality PLCS programming policies? | |||

| Advisory Committees do not exist. | Advisory Committees are implemented but do not collaborate to ensure quality PLCS programming policies. | Committees (Coordinated School Health, CTE program advisory committees) meet a minimum of twice per school year to ensure quality PLCS programming policies. | Advisory Committees (Coordinated School Health, CTE program advisory committees) meet at least quarterly throughout the school year to ensure quality PLCS programming policies. |

| To what extent does school leadership ensure that the school is implementing the district-level wellness policy via a school-level wellness policy that is reviewed annually; and goals for school wellness are included in the Comprehensive School Improvement Plan (CSIP)? | |||

| Only a district-level wellness policy is in place. | A school-level wellness policy is developed but not reviewed annually. | School is implementing the district-level wellness policy via a school-level wellness policy that is reviewed annually; and goals for school wellness are included in the CSIP. | School is implementing the district-level wellness policy via a school-level wellness policy that is reviewed annually; the school utilizes collection of body mass index percentile data in their annual wellness policy review process; and goals for school wellness are included in the CSIP and Comprehensive District Improvement Plan. |

Adapted from the Kentucky Department of Education. Practical Living/Career Studies Program Review. Frankfort, KY: Kentucky Department of Education; 2014. Available at: http://education.ky.gov/curriculum/pgmrev/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed January 15, 2015.

Colorado

In Colorado, strong collaboration and leadership between health and education partners, both public and private, have been instrumental in advancing the integration of health and education across the state. Cooperative relationships have been created by aligning the priorities of local foundations with state-level initiatives rather than passing policy. In addition to a solid working partnership between the state health and education agencies, the state has benefitted from the strategic support of local foundations and organizations including: The Colorado Education Initiative, RMC Health, the Colorado Health Foundation, and Kaiser Permanente. In 2010, these partners came together to develop and disseminate the Healthy School Champion Score Card, a voluntary online school-level assessment tool and associated statewide recognition program that provides financial incentives for creating healthy schools (Tables 2 and 3). The Score Card's design incorporated input from nearly 500 Colorado leaders. It includes 80 questions structured around the 8 components of CSH. Whereas the design is based on the School Health Index, it also takes into consideration Colorado legislation and policies. The use of the Score Card grew significantly from its initiation in 2010, when 100 schools participated. In the 2013–2014 school year, 216 schools, covering over 100,000 students, participated.29,30

Table 2.

Colorado Healthy School Champions Score Card Sections*

| 1 | Description of coordinated school health efforts |

| 2 | Assessment of community, family, and student involvement |

| 3 | Assessment of health education |

| 4 | Assessment of health services |

| 5 | Assessment of nutrition |

| 6 | Assessment of physical education/physical activity |

| 7 | Assessment of staff wellness |

| 8 | Assessment of school counseling, psychological and social work services |

| 9 | Assessment of school environment |

Colorado Coalition for Healthy Schools. Score Card Overview. Available at: http://www.healthyschoolchampions.org/score-card/overview. Accessed January 23, 2015.

Table 3.

Examples From Colorado Healthy School Champions Score Card*

| Description of Coordinated School Health Efforts | ||

|---|---|---|

| Fully in Place | Partially in Place | Not in Place |

| Does your school have an individual who coordinates school health and wellness activities and programs? | ||

| Schools that answer “fully in place” have designated a staff member who has been formally designated as part of his/her job description to coordinate school health and wellness activities and programs. | In schools that answer “partially in place” have a staff member(s) coordinating school health and wellness activities and programs, but it is NOT a part of their job description. | Schools that answer “not in place” do not have a staff member(s) whose formal responsibilities include coordinating school health and wellness activities and programs. |

| Does your school have a team that focuses on improving school health and wellness? | ||

| Schools that answer “fully in place” have a designated team whose members have assumed responsibility for coordinating school health and wellness activities and programs. | In schools that answer “partially in place:” existing teams informally assume these responsibilities. | Schools that answer “not in place” do not have a designated team whose formal responsibilities include coordinating school health and wellness activities and programs. |

| If your school has a school health team, are members representative of all School Health component areas? | ||

| Schools that answer “fully in place” have a designated team whose members include representatives from each of the 8 Coordinated School Health component areas. | In schools that answer “partially in place,” the team has representation from some but not all of the 8 Coordinated School Health component areas. | Schools that answer “not in place” do not have a designated team who coordinate school health and wellness activities and programs. |

| To what extent does the principal of your school support the school health and wellness activities that are under way? | ||

| In schools that answer “fully in place,” the principal demonstrates support for the school health and wellness activities by encouraging staff involvement, giving priority to health activities, promoting wellness, modeling healthy behavior, and providing resource support. | In schools that answer “partially in place,” the principal has taken some actions to support the school health and wellness activities that are under way. | In schools that answer “not in place,” the principal has not taken any actions to support the school health and wellness activities that are under way. |

| To what extent does your school collect, utilize and present data and other information to identify the populations and health issues to be addressed in your school health efforts? | ||

| In schools that answer “fully In place,” data are actively used to prioritize the populations and health issues addressed in school health efforts. | In schools that answer “partially in place,” data actions are limited because information is not updated or complete, or not all priorities are set using data. | In schools that answer “not in place,” no actions are under way to collect, utilize, and/or present data and other information to identify the populations and health issues to be addressed in your school health efforts. |

Colorado Coalition for Healthy Schools. Healthy School Champions Score Card. Available at: http://www.healthyschoolchampions.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/Healthy-School-Champions-Score-Card-9.3.14.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2015.

Colorado is working to build on the success of the Score Card by developing the next phase of a district- and school-level assessment and implementation tool for health policies and practices, called Healthy Schools Smart Source. This effort is funded by Kaiser Permanente, in partnership with the Colorado Department of Education, the Colorado Department of Public Health and the Environment, The Colorado Education Initiative, and the Colorado Coalition for Healthy Schools. The goal of Smart Source is to create a single assessment tool that will incorporate questions from the Score Card and other statewide school health assessments, streamlining data collection and submission for schools.31 To create the assessment, partners conducted an extensive literature review and convened over 200 stakeholders in order to determine the correct data points. A pilot of Smart Source was launched in the 2014–2015 school year with 90 schools. By the 2016–2017 school year, Smart Source will collect and synthesize data about school and district health policies and practices into a statewide system. Smart Source will provide schools with school-level reports that offer objective, meaningful comparisons to the aggregated results from all respondents statewide. These reports are designed to provide useful, actionable data as well as recommendations for implementing best practices related to health and wellness (Table 4). Reports will provide school- and district-level leaders with a more robust picture of the effect their school health efforts have on student performance and classroom behavior, informing the school improvement planning process.31,32

Table 4.

Overview of Colorado Healthy Schools Smart Source*

| Smart Source will decrease duplicative data collection by streamlining multiple survey efforts and recognize exemplar schools and districts in order to replicate best practices. It will also provide a far more robust picture of the effects of their school health efforts through tailored technical assistance and school-level reports. | |

| For statewide funders, organizations, and agencies, it will help assess whether they are “moving the needle” on health and wellness in schools, allocate resources, and inform statewide decisions and legislation. | |

| What smart source is | What smart source is not |

| A school- and district-level tool that collects data about health policies and practices. | A student-level tool that collects data on student attitudes and behaviors. Student-level data are collected via the Healthy Kids Colorado Survey. |

| A system that allows schools and districts to assess their own policy and practices in order to improve school health. | A monitoring system holding schools accountable for implementing school health policies and practices. |

| A tool that reduces the burden on schools by streamlining multiple school health policy and practice data collections into one system. | One of many school-level tools that assess school health policy and practice. |

| A vehicle to help secure funding and resources to improve school health. | A vehicle to highlights schools and districts that are not engaged in health and wellness efforts. |

| An opportunity to recognize schools for the great work they do in health and wellness and replicate best practices. | An opportunity for schools and districts to be penalized for not emphasizing health and wellness efforts. |

| A way to provide reports to schools and districts with meaningful and actionable data. | A system that provides little to no usable data. |

Colorado Education Initiative. Colorado Healthy Schools Smart Source. Available at: http://www.coloradoedinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Smart-Source-Info-Sheet.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2015.

In addition to the Smart Source initiative, collaborating partners have also launched the Colorado Healthy Schools Collective Impact (HSCI), a purposeful and strategic effort to define healthy schools, prioritize school health-related work in the state, minimize duplication of initiatives, and better leverage resources and funding for healthy schools. Healthy Schools Collective Impact members include 20 foundations and nearly 100 community organizations, state agencies, school districts and schools, and nonprofits that are all interested in strengthening the school health environment. The 4 focus areas, each represented by a work group that meets monthly, are PE and physical activity, nutrition, behavioral health (social, emotional, and mental), and student health services. Healthy Schools Collective Impact's objectives are to (1) coordinate efforts and ensure resources are allocated based on identified needs; (2) engage those impacted by the work, including districts and schools, parents, students, funders, and organizations that champion healthy schools; (3) gather consistent data by coordinating surveys and systems to collect data from schools; (4) use consistent communication by creating a shared definition of a healthy school, possibly producing a one-stop shop for data and resources related to priority school health strategies; (5) support core capacity for schools and districts; and (6) develop shared policy priorities.33

Applying the WSCC Model at the Local Level

At the local level, many school districts nationally have embraced the importance of addressing the whole child through better alignment and integration of health and education. Two districts that provide strong examples of application and implementation of Coordinated School Health and/or the WSCC model include Maine Regional School Unit (RSU) #22 and Denver Public Schools in Colorado. Both have benefited from the leadership of superintendents and local school boards that have embraced the importance of educating the whole child.

Maine Regional School Unit #22

Maine Regional School Unit #22, located in the Hampden area, began to intentionally focus on the health and wellness of students and staff in 1991. The vision to strengthen school health and wellness has been driven by Rick Lyons, district superintendent since 1992. The district began by forming a Wellness Team long before the concept had gained widespread popularity. The Wellness Team, comprised administrators, faculty, support staff, and community members, has been a key factor behind the district's school health achievements since its establishment. In 2001, the district also founded a School Health Advisory Council (SHAC) comprised of administrators, healthcare professionals, and community members. The SHAC oversees the CSHP, which is headed by a School Health Coordinator employed by the district. Given RSU #22's small size (approximately 2,200 students and 375 employees), the financial commitment to support a full-time school health coordinator speaks to the high priority that school health has in this district.

Over the last 20 years, RSU #22 has taken many proactive steps toward strengthening school health in each of its 6 schools. The district adopted a tobacco policy in 1994, followed by a nutrition policy. It increased the number of positions and staffing time for health education teachers, nurses, and guidance counselors and forged partnerships with behavioral health providers. The district promotes active transport to school with a “walking school bus,” works with the Hampden Town Council to repair bike lanes and install street lights, and partners with the Hampden Recreation Department to provide before- and after-school programming. Regional School Unit #22 implemented a comprehensive K–12 Health/PE curriculum focusing on lifelong activities (such as weight training, aerobics, bicycling, and running) along with activities such as skiing, tennis, snowshoeing, and swimming and uses Recess Rocks® in K–2 classrooms. In 2002, the Wellness Coordinator and Nutrition Director worked with students and suppliers to change the content of all food offered in vending machines to healthy choices. Regional School Unit #22's schools offer salad bars at lunch, and the food service director strives to use locally sourced foods as much as possible. In 2010, parents, students, the district's food service director, wellness coordinator, and community partners collaborated to plant apple orchards and a vegetable garden.

Leadership from school board members and the superintendent has been key in RSU #22's transformation into a district where health and wellness is a top priority and a value embraced by the school employees and the community. The SHAC, Wellness Team, and school health coordinator have also been integral to the process. They have worked together to facilitate the integration of health and education in numerous areas, including the district's strategic plan and the interview process for prospective employees, which includes questions about their thoughts on the district's wellness priorities. The district has focused on improving student and staff health and dedicated significant financial resources to both. The local school board allocates approximately $40,000 per year for employee wellness incentives for those who did not use more than 3 sick days the previous year, and 60% of staff members have qualified for this reward. Regional School Unit #22 promotes periodic wellness challenges for staff and a 7-week “total health” track through Adult Education. In 2012, it opened a new high school that includes a fitness center, track, and tennis courts open to students, staff, and the community. As a result of these efforts, the Wellness Council of America awarded the district their Gold Level Workplace Wellness award.

Denver Public Schools

Superintendent leadership also has been critical to the success of DPS' strategic inclusion of student health in the district's overall priorities and plan. Since being appointed to the position by the Board of Education in 2009, Superintendent Tom Boasberg has managed the district's 183 schools, which serve a diverse population of over 90,000 children. Seventy-two percent of students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, and 41% speak a language other than English at home.34 The district has also committed significant resources to student health, and made it a part of the district's strategic planning process.

In 2010, Boasberg oversaw the Denver School Health Advisory Council's creation of the DPS Health Agenda 2015, which outlines the districts' health priorities.35 The district has since invested over $22 million toward its health goals, including the addition of 6 full-time district-funded employees. Some of the significant accomplishments include dramatically increasing the number of schools that serve breakfast after the bell; adding PE teachers to elementary schools, which has led to an additional 22 minutes per week of PE classes; and increasing the number of school counselors, which has corresponded with a decrease in expulsion and suspension rates. Denver Public School has also added a school-based health center every year since 2010, with a fifth scheduled to open in 2015.

In August 2014, DPS released the current version of its 5-year strategic plan, Denver Plan 2020. This version, which was developed with the input of nearly 3,000 educators, parents, students, community partners, and city leaders, includes “Support for the Whole Child” as one of 5 goals. Using the WSCC model as a backbone, an advisory committee is assessing DPS' activities, and will present recommendations for creating a metric to determine future progress in early 2015.36 Denver Public School is also working on the development of the next generation of their health agenda, DPS Health Agenda 2020. The district has solicited input from students, parents, and community members through a widely disseminated survey about health issues that most impact students. Survey topics include asthma, vision, oral health, nutrition, physical activity, social/emotional health, substance abuse, teen pregnancy, and school culture. Denver Public School plans to use the results of this survey to improve student health and wellness going forward.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SCHOOL HEALTH

The WSCC model provides a framework for the health and education sectors at the state and local levels to work toward stronger alignment, integration, and collaboration. As Lloyd Kolbe stated, the WSCC model provides a new opportunity, impetus, and sense of purpose for both sectors: “If we prudently could unite the expertise, perspectives, resources, communication, visibility, and political support of national education, health, and related organizations to help schools and colleges implement a WSCC approach, we synergistically could increase the impact of each sector, each organization involved; we could build a lasting national base for new means to improve both education and health; we could accomplish that which we otherwise cannot.”37

Whereas the WSCC model is new, having been launched in March 2014, many states and local school districts are already in the process of adapting and adjusting practices and processes to suit the expanded version of CSH. The 3 states and 2 school districts highlighted all provide strong examples of implementation of various aspects of the WSCC model. They demonstrate that it is possible to prioritize student health within the education system, for the purpose of better addressing the needs of the whole child. They also demonstrate the importance of strategic leadership at the state and local level, including support from policymakers, superintendents, local school boards, and community organizations that recognize and seize opportunities to integrate and better align the health and education sectors.

Moving forward, state and local health and education agencies should focus greater attention toward ensuring the adoption and implementation of policies that serve both sectors and students, and promote the formation of collaborative partnerships. Policymakers need to focus on adoption and implementation of policies and practices that build on the connection between the school health components and educational outcomes, both academic and behavioral. When those in decision-making roles understand and embrace the WSCC model, they are able to create programs and policies that lead to collaboration and more effective use of resources, creating healthier school environments that address the needs of the whole child.

Human Subjects Approval Statement

Information contained in this article was not deemed to involve human subjects, and therefore, was considered exempt from institutional review board examination.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fedewa AL, Ahn S. The effects of physical activity and physical fitness on children's achievement and cognitive outcomes: a meta-analysis. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2011;82(3):521–535. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2011.10599785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health and academic achievement. 2014. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/health_and_academics/pdf/health-academic-achievement.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2015.

- 3.Basch C. Healthier Students Are Better Learners: A Missing Link in Efforts to Close the Achievement Gap. New York, NY: Columbia University; 2010. Available at: http://www.equitycampaign.org/i/a/document/12557_ EquityMattersVol6_Web03082010.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2015.

- 4.Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA., Jr Food insufficiency and American school-aged children's cognitive, academic, and psychosocial development. Pediatrics. 2001;108(1):44–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradley BJ, Greene AC. Do health and education agencies in the United States share responsibility for academic achievement and health? A review of 25 years of evidence about the relationship of adolescents' academic achievement and health behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(5):523–532. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldman D, Smith JP. The increasing value of education to health. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(10):1728–1737. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute of Medicine. Exploring Opportunities for Collaboration between Health and Education to Improve Population Health: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ASCD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child: A Collaborative Approach to Learning and Health. Alexandria, VA: ASCD; 2014. Available at: http://www.ascd.org/ASCD/pdf/siteASCD/publications/wholechild/wscc-a-collaborative-approach.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blank M, Jacobson R, Melaville A, Pearson S. Financing Community Schools: Leveraging Resources to Support Student Success. Washington, DC: Coalition for Community Schools, Institute for Educational Leadership; 2010. Available at: http://www.communityschools.org/assets/1/AssetManager/finance-paper.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durant N, Harris SK, Doyle S, et al. Relation of school environment and policy to adolescent physical activity. J Sch Health. 2009;79(4):153–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00384.x. quiz 205–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maddock J, Choy LB, Nett B, McGurk MD, Tamashiro R. Increasing access to places for physical activity through a joint use agreement: a case study in urban Honolulu. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(3):A91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo JJ, Jang R, Keller KN, McCracken AL, Pan W, Cluxton RJ. Impact of school-based health centers on children with asthma. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37(4):266–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaplan DW, Calonge BN, Guernsey BP, Hanrahan MB. Managed care and school-based health centers. Use of health services. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152(1):25–33. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santelli J, Kouzis A, Newcomer S. School-based health centers and adolescent use of primary care and hospital care. J Adolesc Health. 1996;19(4):267–275. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(96)00088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olshansky SJ, Antonucci T, Berkman L, et al. Differences in life expectancy due to race and educational differences are widening, and many may not catch up. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(8):1803–1813. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schiller JS, Lucas JW, Peregoy JA. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: national health interview survey, 2011. Vital Health Stat. 2012;10(256):1–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. An act to create a child health advisory committee. 2003; Act 1220 (Arkansas 84th General Assembly)

- 18. An act to increase academic instruction time in public schools; to limit physical activity requirements for public school students; and for other purposes. 2007; Act 317(Arkansas 86th General Assembly)

- 19. An act to increase the tax on cigarettes and other tobacco products; to authorize the department of finance and administration to pay the commission to the stamp deputies for certain cigarette taxes; and for other purposes. 2009; Act 180 (Arkansas 87th General Session)

- 20.Phillips M, Raczynski J, Walker J Act 1220 Evaluation Team. Year Seven Evaluation: Act 1220 of 2003 of Arkansas to Combat Childhood Obesity. Little Rock, AR: Fay W. Boozman College of Public Health, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences; 2011. Available at: http://publichealth.uams.edu/files/2012/06/COPH-Year-7-Report-Sept-2011.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raczynski JM, Thompson JW, Phillips MM, Ryan KW, Cleveland HW. Arkansas act 1220 of 2003 to reduce childhood obesity: its implementation and impact on child and adolescent body mass index. J Public Health Policy. 2009;30(Suppl 1):S124–S140. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2008.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krukowski RA, West DS, Siddiqui NJ, Bursac Z, Phillips MM, Raczynski JM. No change in weight-based teasing when school-based obesity policies are implemented. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(10):936–942. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.10.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Philips M, Raczyinski J, Walker J Act 1220 Evaluation Team. Year Six Evaluation: Act 1220 of 2003 of Arkansas to Combat Childhood Obesity. Little Rock, AR: Fay W. Boozman College of Public Health, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences; 2010. Available at: http://www.uams.edu/coph/reports/Year%206%202009/Y6_ExSum_2009.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phillips M, Raczynski J, Walker J Act 1220 Evaluation Team. Establishing a Baseline to Evaluate Act 1220 of 2003: An Act of the Arkansas General Assembly to Combat Childhood Obesity. Little Rock, AR: Fay W Boozman College of Public Health, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences; 2005. Available at http://www.uams.edu/coph/reports/2004Act12202003Y1Eval.pdf. Accessed Jaunary 15, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phillips M, Raczynski J, Walker J Act 1220 Evaluation Team. Year Two Evaluation: Arkansas Act 1220 of 2003 to Combat Childhood Obesity. Little Rock, AR: Fay W. Boozman College of Public Health, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences; 2006. Available at: http://www.uams.edu/coph/reports/2004Act1220Eval.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phillips M, Raczynski J, Walker J Act 1220 Evaluation Team. Year Three Evaluation: Arkansas Act 1220 of 2003 to Combat Childhood Obesity. Little Rock, AR: Fay W. Boozman College of Public Health, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences; 2007. Available at http://www.uams.edu/coph/reports/2006Act1220_Year3.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phillips MM, Raczynski JM, West DS, Pulley L, Bursac Z, Leviton LC. The evaluation of Arkansas Act 1220 of 2003 to reduce childhood obesity: conceptualization, design, and special challenges. Am J Community Psychol. 2013;51(1–2):289–298. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9538-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. An act relating to student assessment. 2009; Senate Bill 1 (Kentucky 09 Regular Session)

- 29. Colorado Education Initiative, Colorado Department of Education. Healthy school champions score card. No date. Available at http://www.healthyschoolchampions.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/Healthy-School-Champions-Score-Card-9.3.14.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2015.

- 30. Colorado Education Initiative, Colorado Department of Education. 2014 healthy school champions: recognizing the health of Colorado schools. Available at: http://www.healthyschoolchampions.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/HSC2014MagazineF.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2015.

- 31. Colorado Department of Education, Colorado Education Initiative. Colorado healthy schools smart source frequently asked questions. 2014. Available at: http://www.cde.state.co.us/nutrition/schoolwellnesssmartsourcefaq. Accessed January 15, 2015.

- 32. Colorado Department of Education, Education Data Advisory Committee. Scheduled data review meeting October 3, 2014. 2014. Available at: http://www.cde.state.co.us/cdereval/october3rdedacminutes. Accessed January 15, 2015.

- 33. Colorado Education Initiative. Colorado healthy schools collective impact. Available at: http://www.coloradoedinitiative.org/our-work/health-wellness/healthy-schools-collective-impact/. Updated 2014. Accessed January 15, 2015.

- 34. Denver Public Schools. Denver plan 2020: Every child succeeds. No date. Available at: http://www.boarddocs.com/co/dpsk12/Board.nsf/files/9RSQ277A4AD9/$file/Whole%20Child%20at%20BoE%20Work%20Session%20v3.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2015.

- 35. Denver Public Schools. DPS Health Agenda 2015: Healthy Kids Learn Better. 2010; Available at: http://staticdpsk12org/gems/healthyschools/DPSHealthAgendaFINALOct2010Webpdf. Accessed January 5, 2015.

- 36. Denver Public Schools. Denver Plan 2020: Every Child Succeeds. Available at: http://www.boarddocs.com/co/dpsk12/Board.nsf/files/9RSQ277A4AD9/$file/Whole%20Child%20at%20BoE%20Work%20Session%20v3.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2015.

- 37.Kolbe LJ. On national strategies to improve both education and health – an open letter. J Sch Health. 2015;85(1):1–7. doi: 10.1111/josh.12223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]