Abstract

Shared latent dimensions may account for the co-occurrence of multiple forms of psychological dysfunction. However, this conceptualization has rarely been integrated into the smoking literature, despite high levels of psychological symptoms in smokers. In this study, we used confirmatory factor analysis to compare three models (1-factor, 2-factor [internalizing-externalizing], and 3-factor [low positive affect-negative affect-disinhibition]) of relations among nine measures of affective and behavioral symptoms implicated in smoking spanning depression, anxiety, happiness, anhedonia, ADHD, aggression, and alcohol use disorder symptoms. We then examined associations of scores from each of the manifest scales and the latent factors from the best-fitting model to several smoking characteristics (i.e., experimentation, lifetime established smoking [≥100 cigarettes lifetime], age of smoking onset, cigarettes/day, nicotine dependence, and past nicotine withdrawal). We used two samples: (1) College Students (N =288; mean age =20; 75 % female) and (2) Adult Daily Smokers (N=338; mean age=44; 32 % female). In both samples, the 3-factor model separating latent dimensions of deficient positive affect, negative affect, and disinhibition fit best. In the college students, the disinhibition factor and its respective indicators significantly associated with lifetime smoking. In the daily smokers, low positive and high negative affect factors and their respective indicators positively associated with cigarettes/day and nicotine withdrawal symptom severity. These findings suggest that shared features of psychological symptoms may be parsimonious explanations of how multiple manifestations of psychological dysfunction play a role in smoking. Implications for research and treatment of co-occurring psychological symptoms and smoking are discussed.

Keywords: Negative affect, Positive affect, Disinhibition, Smoking

The link between many different types of psychological and behavioral symptoms (e.g., low positive affect, negative affect, attentional control, impulsivity, aggression, alcohol misuse) and various stages of smoking (e.g., initiation, progression to heavy smoking, nicotine dependence, and difficulties quitting) is well-documented (Audrain-McGovern, Rodriguez, Tercyak, Neuner, and Moss 2006; Breslau, Novak, and Kessler 2004; Doran, Spring, McChargue, Pergadia, and Richmond 2004; Gehricke et al. 2007; Kollins, McClernon, and Fuemmeler 2005; Lasser et al. 2000; Leventhal et al. 2012; Leventhal, Ramsey, Brown, LaChance, and Kahler 2008; Rohde, Lewinsohn, Brown, Gau, and Kahler 2003). However, much of this research has examined different types of psychological symptoms in isolation from one another. This may pose a barrier to pinpointing the most prominent psychological sources of smoking due to widespread co-occurrence across many types of psychological dysfunction (Clark, Watson, and Reynolds 1995). Specifically, without accounting for psychological comorbidity, it is unclear whether relations documented between various manifestations of psychological symptoms and smoking are: (1) unique from one another and due to features specific to certain types of psychological symptoms; or (2) common to one another and explained by features shared among many different types of psychological symptoms.

Psychological comorbidity may best be understood in terms of broad higher-order dimensions, such that individual manifest disorders reflect different expressions of a smaller set of common underlying liabilities (Brown and Barlow 2009; Krueger and Markon 2006). One possibility is that a single latent dimension of general maladjustment represents a broad propensity for nearly any type of psychological dysfunction (Krueger, Caspi, Moffitt, Silva, and McGee 1996). A second hypothesis is that most psychiatric disorders are best modeled by two underlying, correlated dimensions: internalizing (psychological maladjustment is primarily expressed inward; unipolar mood and anxiety disorders) and externalizing (maladjustment is primarily expressed outward; disruptive behavior and substance use disorders) (Krueger and Markon 2006; Krueger 1999). A third hypothesis by Clark (2005) is that all forms of personality and psychopathology develop from three underlying dimensions: two affective systems - positive affectivity, which mainly associates inversely with depression, and negative affectivity, which underlies a broad range of psychopathology (Clark and Watson 1991) - and one regulatory system – disinhibition, a reduced ability to control behavioral impulses, which associates with a range of externalizing disorders (Lynam, Leukefeld, and Clayton 2003). It is also possible that the hypothesized latent factors (e.g., internalizing, externalizing) load onto a single second-order factor of general maladjustment. These two levels of factors may reflect: (1) broadband-specific features, which distinguish related groups of disorders from each other (e.g., internalizing vs. externalizing) and (2) common features shared across nearly all forms of psychological dysfunction (Ingram and Kendall 1987).

The aforementioned structural models of psychological dysfunction have largely not been incorporated into the smoking literature, which is an important gap for several reasons. First, this approach may help clarify mechanisms underlying the link between psychological symptoms and smoking. For example, it has been hypothesized the individuals with psychological symptoms smoke for self-medication purposes (e.g., to regulate emotions; Gehricke et al. 2007). However, without accounting for psychological comorbidity, it is unclear whether these individuals are smoking to self-medicate unique aspects of a certain psychological dysfunction (e.g., somatic symptoms of anxiety) or features shared across many different types of psychological dysfunction (e.g., proneness to negative moods). Second, this approach will shed light on whether there may be underlying liabilities (e.g., maladaptive temperaments) to developing manifest disorders that directly influence smoking, which will help provide insight into etiologic processes between psychological symptoms and smoking. Third, this technique provides a parsimonious way to account for the association of smoking with many different manifest forms of psychological dysfunction and may organize a literature that is often fragmented into specific lines of research focusing on a particular diagnostic category (e.g., major depression, panic disorder).

In this study, confirmatory factor analysis was used to test 1-factor, 2-factor, and 3-factor structural models to establish a parsimonious and meaningful latent factor model of a set of manifest psychological and behavioral symptom scales. These scales include: happiness, low positive affect, anhedonia, depression, anxiety, anxious arousal, ADHD symptoms, physical aggression, and alcohol use disorder symptoms. We investigated these scales because they are components of more prevalent types of disorders (i.e., mood, anxiety, disruptive behavior, antisocial, and alcohol use; Babor, Biddle-Higgins, Saunders, and Monteiro 2001; Brown, Chorpita, and Barlow 1998; Fossati et al. 2007; Gehricke and Shapiro 2000; Kessler et al. 2005a; Kessler et al. 2005b; Mineka, Watson, and Clark 1998), they have received significant attention in the smoking literature (e.g., Audrain-McGovern et al. 2006; Kollins et al. 2005; Lasser et al. 2000; Lepper 1998; Leventhal et al. 2008; Nabi et al. 2010), and they provide adequate representation of constructs that could map onto any one of the three tested models. These scales were also selected because they are overlapping to a certain extent, both conceptually and empirically, and this overlap may tap into shared latent constructs that are unidentifiable using the individual manifest indicators.

Furthermore, these scales integrate symptom-specific (e.g., anhedonia), syndrome-specific (e.g., ADHD), and cross-cutting (e.g., aggression) constructs, which has several benefits. Unlike measures which assume homogeneity across syndromes (e.g., presence vs. absence of major depression), using multiple levels of indicators addresses heterogeneity of symptoms within syndromes (e.g., anhedonia versus negative affect in depression; Watson et al. 1995b) by not combining different symptom types into one scale. This is important for latent structural modeling because it permits interpretation of how putatively distinct symptom components differentially load onto latent factors, thereby providing more precise information about the composition of latent factors. Also, examining psychological constructs from a continuous (versus categorical) perspective and in non-patient (versus psychiatric patient) samples is important given associations demonstrated between smoking and continuous measures of psychological symptoms at low levels (e.g., >1 ADHD symptom, Elkins, McGue, and Iacono 2007; >2 depressive symptoms, Niaura et al. 2001) and in individuals that do not have the respective current psychiatric disorder (Heffner, Johnson, Blom, and Anthenelli 2010; Leventhal et al. 2008).

This study also investigated associations of smoking characteristics to: (1) scores on each of the psychological and behavioral symptom scales and (2) factor scores derived from the latent factors in the best-fitting model. The goal was to elucidate whether shared features of psychological symptoms meaningfully associate with smoking. Because psychological symptoms may vary across demographic characteristics (Kessler et al. 2005a), we examined model fit of the 1-factor, 2-factor, and 3-factor models in two diverse samples - college students and adult smokers - to shed light on the generalizability of the structural models across different populations. Including these two samples also allowed for the ability to examine relations with several smoking variables – smoking experimentation (i.e., ever smoke a cigarette) and established smoking (smoked 100+ cigarettes) in the college students and age of smoking onset, cigarettes per day, nicotine dependence, and retrospective nicotine withdrawal symptoms in the adult smokers. Furthermore, although the two samples were demographically unique and applied distinct measures of smoking which limited direct comparisons, including both samples allowed for the ability to see whether the results replicate across the different samples, which decreases the likelihood that the findings are dependent on the specific sample or measures being used.

We hypothesized that a 2-factor internalizing (happiness, anhedonia, depression, anxiety, anxious arousal) and externalizing (physical aggression, ADHD symptoms, alcohol use) model would provide the best fit for the data, based on the high consistency of support found for the 2-factor model (Cosgrove et al. 2011; Krueger and Markon 2006; Krueger 1999; Slade and Watson 2006). Furthermore, because the psychological symptom scales included in the model are significantly associated with disorders that loaded onto the internalizing and externalizing factors in these prior studies (i.e., happiness (low), anhedonia, and depressive symptoms with depressive disorders, Brown et al. 1998; Gehricke and Shapiro 2000, anxious symptoms and anxious arousal with anxiety disorders, Brown et al. 1998; Mineka et al. 1998, physical aggression with antisocial disorder, Fossati et al. 2007, ADHD symptoms with ADHD, Kessler et al. 2005a, and alcohol use disorder symptoms with alcohol use disorders, Babor et al. 2001), we speculated that these symtpom scales would demonstrate a similar 2-factor structure. We also hypothesized that the latent factor scores would associate with the smoking variables in a similar manner to the manifest scales because we speculate that the shared features that account for psychological comorbidity may underlie many relations between psychological symptoms and smoking.

Method

This study is a secondary analysis consisting of two samples from two separate larger studies. For the first sample (study sample 1), data is from a correlational survey study of health behaviors and their relations with mental health, personality, and health behaviors in college students. For the second sample (study sample 2), data were obtained from a study of the influence of individual differences in psychological symptoms on sensitivity to the effects of tobacco deprivation in adult daily smokers (Masked for Review, 2014). Both studies were approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board.

Participants and Procedures

Study Sample 1: College Students

Participants were 288 undergraduate and graduate students enrolled at the University of Southern California. Fliers, class announcements, electronic postings, and human subject participation pools were used to recruit students. Inclusion criteria were: 1) ≥18 years of age, 2) fluent in English, 3) able to provide informed consent, and 4) currently enrolled at the University of Southern California. Participation involved attending one in-person data collection session, conducted by trained research staff, in which participants completed several questionnaires.

Study Sample 2: Adult Daily Smokers

Participants were adult current smokers recruited through community advertisements (e.g., newspaper, online) and referrals. Inclusion criteria were:1) ≥18 years of age, 2) regular cigarette smoker for ≥2 years, 3) currently smoke ≥10 cigarettes per day, 4) normal or corrected-to-normal vision with no color blindness and 5) fluent in English. Exclusion criteria were: 1) active DSM-IV non-nicotine substance dependence, 2) current DSM-IV mood disorder or psychotic symptoms (to minimize cognition-impairing effects of acute and severe psychiatric dysfunction) based on results from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP; First et al. 2002), 3) breath carbon monoxide (CO) levels <10 ppm at intake, 4) use of non-cigarette forms of tobacco or nicotine products, 5) plans to quit smoking within 30 days, 6) use of psychiatric medications, or 7) pregnant. Participants were compensated between $204 and $212 for completing the entire study (range due to performance on tasks not included in this paper). Following an initial phone screen, participants attended an in-person baseline session involving informed consent, breath CO analysis, psychiatric screening interview by a trained research assistant to assess eligibility, and measures of psychological symptoms and smoking. Of the 515 adult smokers recruited for the study, 165 were ineligible (main reasons were low baseline CO (N= 103) and current psychiatric disorder (N=39)), 7 declined to participate, and 5 had unclear responses on some of the main smoking variables, leaving a final sample of 338 included in the analyses.

Measures

Participants completed the following self-report scales to assess psychological symptoms.

The Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS; Lyubomirsky and Lepper 1999) is a 4-item measure of global subjective happiness. Items are rated on a 7-point scale, and an overall mean score was computed.

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: Anhedonia Subscale (CESD:ANH; Radloff 1977) is a sub-scale on the 20-item CESD and contains four reverse-scored items relating to feelings of happiness and hopefulness, which were averaged to create a mean score. Participants rate how often they have felt a certain way “during the past week” on a 4-point scale. Confirmatory factor analyses have supported the CESD:ANH subscale (Shafer 2006) and prior studies have shown this subscale associates with smoking characteristics (Leventhal et al. 2008; Pomerleau, Zucker, and Stewart 2003).

The Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire-Short Form (MASQ-SF; Watson et al. 1995a, b) is a 62-item measure of affective symptoms. Participants rate how much they experienced each symptom “during the past week, including today” (1=Not at all to 5=Extremely). The MASQ contains four subscales: 1) Anxious Arousal (MASQ:AA), a measure of somatic tension and hyperarousal, 2) Anhedonic Depression (MASQ:AD), a measure of loss of interest in life, with reverse-keyed items measuring positive affect, 3) General Distress-Depression (MASQ:GDD), a measure of non-specific depressed mood experienced in both depression and anxiety, and 4) General Distress-Anxiety (MASQ:GDA), a measure of non-specific anxious mood experienced in both anxiety and depression. Sum scores were calculated for each of the scales.

The Aggression Questionnaire-Revised: Physical Aggression (AQR:PA; Bryant and Smith 2001) is a 3-item subscale on the 12-item Aggression Questionnaire-Revised that assesses disposition to physical aggression. Confirmatory factor analysis has supported the empirical uniqueness of this subscale (Bryant and Smith 2001). Participants rate how characteristic the statements are of them on a 6-point scale. A mean score across the items was computed.

The Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS; Kessler et al. 2005a) is measure of ADHD symptoms in adults and includes 9 inattentive items and 9 hyperactive-impulsive items. Participants rate each item based on how often they have felt and conducted themselves over the past 6 months (1=Never to 5=Very often). Following prior work (Kessler et al. 2005a), a total mean score was calculated across the 18 items.

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor et al. 2001) is a 10-item measure of hazardous alcohol use, alcohol dependence symptoms, and harmful alcohol use. Response options range from 0 to 4, with higher scores reflecting more problematic alcohol use. Participants received a sum score for the scale.

The dependent variables in the regression models encompass several smoking behaviors and characteristics. Different questionnaires were used across the two samples to collect this information. In the college students, the Tobacco and Alcohol Use History Survey (Pierucci-Lagha et al. 2005) was administered to assess two self-report items: 1) ever smoke a cigarette (yes/no), and 2) smoked 100+ cigarettes in lifetime (yes/no). In the adult smokers, the Smoking History Questionnaire measured self-report information on: 1) age of onset of regular smoking, 2) average number of cigarettes smoked per day, and 3) severity of retrospective withdrawal symptoms. For withdrawal symptoms, participants rated how severe (1=Not at all to 5=Very severe) they experienced seven withdrawal symptoms (i.e., cLravings, irritability, nervousness, difficulty concentrating, physical symptoms, difficulty sleeping, loss of interest or pleasure) in their most recent attempt to quit smoking, which were averaged to create a reliable construct (α=.88). Additionally, the Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence (FTND; Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, and Fagerstrom 1991), a well-validated, 6-item self-report measure of nicotine dependence severity, was given to evaluate nicotine dependence severity in the adult smokers.

Data Analysis

Preliminary Analyses

To examine psychological severity of the samples, the proportions of individuals who scored above established cut-off points on relevant scales (i.e., MASQ scales, Schulte-van Maaren et al. 2012; ASRS, Kessler et al. 2005a AUDIT, Babor et al. 2001) were calculated. Because certain psychological measures were added throughout the studies, participants in the early months of the studies were not administered some of the measures. Hence, there is a range of missing data on these measures in both samples. Complete N′s for the scales in the college students are (out of 288): SHS (265), CESD (288), MASQ (287), AQR (283), ASRS (287), AUDIT (285); and in the adult smokers are (out of 338): SHS (324), CESD (338), MASQ (324), AQR (278), ASRS (252), AUDIT (202). All preliminary analyses were conducted in SAS v9.2 (SAS Institute Incorportated 2009) and based on complete, non-missing data. Procedures for handling missing data for primary analyses are discussed in the next section.

Primary Analyses

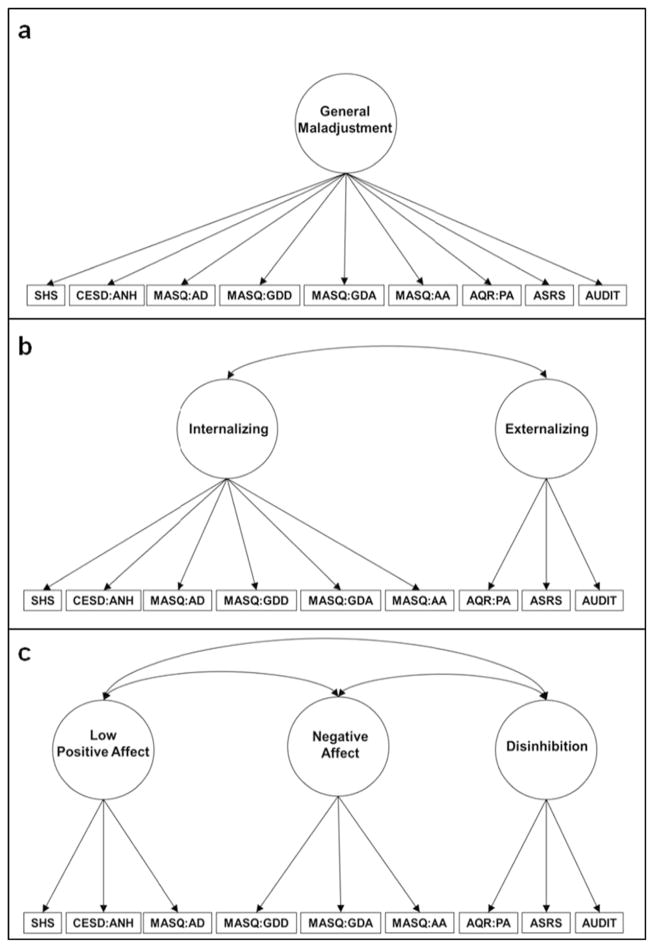

Confirmatory factor analytical models (CFA) were developed to investigate the relations of the set of psychological symptoms scales within each sample: (1) a 1-factor model in which all scales loaded onto 1-factor of general psychological maladjustment, (2) a 2-factor model in which the SHS, CESD:ANH, MASQ:AD, MASQ:GDD, MASQ:GDA, and MASQ:AA loaded onto an internalizing factor and the AQR:PA, ASRS, and AUDIT loaded onto an externalizing factor, and, (3) a 3-factor model in which the SHS, CESD:ANH, and MASQ:AD loaded onto a low positive affect factor, the MASQ:GDD, MASQ:GDA, MASQ:AA loaded onto a negative affect factor, and the AQR:PA, ASRS, and AUDIT loaded onto a disinhibition factor (see Fig. 1). For the best-fitting model, we also developed a model with a higher order factor of general psychological maladjustment to account for the possibility that there may be different levels of shared features (Ingram and Kendall 1987; Weiss, Susser, and Catron 1998). All CFA were conducted in Mplus v6 (Muthen and Muthen 1998–2010), based on the analysis of covariance, and used maximum likelihood estimation (ML), which is recommended to handle missing data in SEM (Allison 2003). Therefore, full samples (Study Sample 1: College Students, N=288; Study Sample 2: Adult Daily Smokers, N=338) were used for primary analyses. ML estimation with robust standard errors (MLR) was used to account for potential multivariate non-normality.

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized 1-factor model of psychological scales. b. Hypothesized 2-factor model of psychological scales. c. Hypothesized 3-factor model of psychological scales. SHS Subjective Happiness Scale, CESD:ANH Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression-Anhedonia Scale, MASQ Mood and Anxiety Symptom Scale AD Anhedonic Depression Scale, GDD General Distress Depression Scale, GDA General Distress Anxious Scale, AA Anxious Arousal Scale, AQR:PA Aggression Questionnaire Revised-Physical Aggression Scale, ASRS Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale, AUDIT Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Error terms associated with each psychological scale are not shown

Model fit evaluation was based on: 1) a non-significant Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square statistic (S-B χ2; Satorra and Bentler 1994), which is considered more appropriate when data are not normally distributed (Chou, Bentler, and Satorra 1991), 2) a comparative fit index (CFI)>.95, and 3) a root mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA)<.06 (Hu and Bentler 1999). Within each sample, the Satorra-Bentler scaled difference chi-square statistic (Satorra and Bentler 2001) was used to compare each of the nested competing models (1-factor vs. 2-factor, 2-factor vs. 3-factor) to determine which model fit the data best in that particular sample. Meaningful empirical modifications to improve model fit were considered using the modification indices option. Once the best-fitting model was established, factor scores for each of the latent factors were computed in Mplus, which uses the modal posterior estimate regression method.

Subsequently, several regression models were tested for each smoking characteristic. These included: (a) separate regression models with scores on each of the manifest psychological scales as predictors and; (b) separate regression models with factor scores on each of the latent factors from the best-fitting model as predictors. In the college students, multiple logistic regression was used for the two dichotomous smoking variables (ever smoke and smoke 100+ cigarettes). In the adult smokers, multiple linear regression was used for the four continuous smoking variables (age of onset, cigarettes per day, FTND, retrospective withdrawal symptom severity). Due to significant associations between age, gender, and race/ethnicity with some of the psychological scales and some of the smoking variables in both samples, these variables were included as covariates in all models. Because of low cell counts, race/ethnicity was reduced into fewer categories: Asian, White, and Other in the college students; Black/African American, White, and Other in the adult smokers. Results are reported as standardized odds ratios (ORs) in the college students and standardized beta weights (βs) in the adult smokers. For all analyses, conclusions were based on a significance level of p<.05 without adjustment for multiple tests because the main purpose of this study was to provide insight into the influence of shared latent psychological dimensions on smoking. However, regression analysis results are presented before and after applying the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995) to illustrate which results did not pass this test and should be interpreted with caution.

Results

Preliminary Results

Illustrated in Table 1, the college students were mainly female, late adolescence/young adult, White or Asian, and non-Hispanic. A little less than half had ever smoked a cigarette and only a small portion had smoked 100+ cigarettes in their lifetime. The adult smokers were primarily male, middle-aged, Black or White, and non-Hispanic. They began smoking regularly around late adolescence/young adulthood, smoked approximately 17 cigarettes per day, had moderate levels of nicotine dependence, and experienced mild to moderate withdrawal symptoms on their most recent quit attempt. In both samples, scores on most of the psychological scales reflected low severity of psychological symptoms and were comparable to other similar study samples of college students and community residents/adult smokers (Borders, Earleywine, and Jajodia 2010 [AQR:PA]; Gerevich, Bacskai, and Czobor 2007 [AQR:PA]; Leventhal et al. 2008 [CESD:ANH]; Lyubomirsky and Lepper 1999 [SHS]; Watson et al. 1995a [MASQ]). Table 2 shows the percent of participants who were above clinically relevant cut-off points on scales. Correlations among the psychological scales showed a wide degree of intercorrelation magnitudes across variables in both samples (see Table 3).

Table 1.

Selected demographic and smoking characteristics

| Variable | Study Sample 1: College Students N=288 |

Study Sample 2: Adult Daily Smokers N=338 |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | M (SD) / % | M (SD) / % |

| Gender (female) | 74.7 % | 32.3 % |

| Race | ||

| Black | 4.5 % | 51.9 % |

| White | 37.7 % | 34.7 % |

| Asian | 36.3 % | 0.9 % |

| Multi-Racial | 11.4 % | 4.2 % |

| Other | 10.1 % | 8.3 % |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | 14.4 % | 14.8 % |

| Age | 19.8 (1.7) | 43.8 (10.8) |

| Smoking Characteristics | ||

| Ever Smoke a Cigarette (yes) | 39.5 % | —— |

| Ever Smoke 100 Cigarettes (yes) | 10.5 % | —— |

| Age Onset | —— | 19.2 (5.5) |

| Cigs/Day | —— | 16.8 (6.8) |

| FTND | —— | 5.3 (1.9) |

| Withdrawal Symptoms | —— | 2.5 (0.9) |

M (SD) =Mean (Standard Deviation). Ever Smoke =ever smoked a cigarette (yes/no). Smoke 100 =Smoked 100 cigarettes in lifetime (yes/ no). Age Onset =age first started smoking regularly. Cigs/Day =average number of cigarettes smoked per day. FTND =Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence. Withdrawal Symptoms =severity of withdrawal symptoms in most recent quit attempt (1=Not at all to 5=Very severe)

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of manifest psychological scales in the structural models

| Scales | Range | Study sample 1: College students

|

Study sample 2: Adult daily smokers

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | Alpha | %>Cut-off | M (SD) | Alpha | %>Cut-off | ||

| SHS | 1–7 | 5.05 (1.20) | .85 | – | 5.28 (1.07) | .76 | – |

| CESD:ANH | 0–3 | 0.88 (0.70) | .83 | – | 0.72 (0.65) | .67 | – |

| MASQ:AD | 22–110 | 55.56 (15.60) | .93 | 58.2 % | 52.58 (14.11) | .89 | 54.9 % |

| MASQ:GDD | 12–60 | 21.82 (9.52) | .94 | 33.8 % | 17.60 (7.02) | .92 | 19.4 % |

| MASQ:GDA | 11–55 | 18.59 (6.40) | .83 | 30.3 % | 15.17 (5.52) | .87 | 13.3 % |

| MASQ:AA | 17–85 | 22.89 (7.37) | .88 | 9.0 % | 21.66 (6.79) | .89 | 8.0 % |

| AQR:PA | 1–6 | 1.80 (0.94) | .68 | – | 1.82 (1.06) | .77 | – |

| ASRS | 0–18 | 2.60 (0.49) | .85 | 18.8 % | 2.18 (0.64) | .92 | 8.7 % |

| AUDIT | 0–40 | 5.56 (5.16) | .84 | 28.7 % | 3.50 (4.86) | .88 | 9.9 % |

N=288 in Study Sample 1: College Students. N=338 in Study Sample 2: Adult Daily Smokers. M (SD) =Mean (Standard Deviation). Alpha =Cronbach’s alpha. % >Cut-off =percent of participants who were above established clinically relevant cut-off points on questionnaires. SHS Subjective Happiness Scale, CESD:ANH Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression-Anhedonia Scale, MASQ Mood and Anxiety Symptom Scale:, AD Anhedonic Depression Scale, GDD General Distress Depression Scale, GDA General Distress Anxious Scale, AA Anxious Arousal Scale, AQR:PA Aggression Questionnaire Revised-Physical Aggression Scale, ASRS Adult ADHD Self-Report Scalem, AUDIT Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

Table 3.

Correlations between manifest psychological scales in the structural models

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SHS | – | −.58† | −.59† | −.45† | −.21† | −.16** | −.16** | −.10 | .08 |

| 2. CESD:ANH | −.44† | – | .76† | .61† | .37† | .29† | .13* | .26** | −.01 |

| 3. MASQ:AD | −.59† | .56† | – | .74† | .47† | .40† | .18** | .28† | −.01 |

| 4. MASQ:GDD | −.34† | .30† | .43† | – | .71† | .59† | .14* | .38† | .04 |

| 5. MASQ:GDA | −.27† | .22† | .31† | .81† | – | .75† | .17** | .40† | .03 |

| 6. MASQ:AA | −.24† | .19† | .28† | .67† | .83† | – | .19** | .43† | .06 |

| 7. AQR:PA | −.16** | .15* | .12* | .26† | .31† | .34† | – | .24† | .20† |

| 8. ASRS | −.22† | .24† | .33† | .45† | .53† | .49† | .36† | – | .24† |

| 9. AUDIT | −.06 | .14* | .01 | .07 | .04 | .08 | .24† | .18** | - |

Correlations on the upper right diagonal refer to Study Sample 1: College Students (N=288). Correlations on the lower left diagonal refer to Study Sample 2: Adult Daily Smokers (N =338). SHS Subjective Happiness Scale, CESD:ANH Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression-Anhedonia Scale, MASQ Mood and Anxiety Symptom Scale, AD Anhedonic Depression Scale, GDD General Distress Depression Scale, GDA General Distress Anxious Scale, AA Anxious Arousal Scale, AQR:PA Aggression Questionnaire Revised-Physical Aggression Scale, ASRS Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale, AUDIT Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Primary Results

Confirmatory Factor Analyses

Within each sample, the fit indices improved and the Satorra-Bentler scaled difference chi-square statistic was significant for each subsequent model (Table 4). The 3-factor model provided the best fit for the data within both samples; however, fit indices still largely did not meet recommended criteria. In both samples, the modification indices output suggested that loading non-specific depressed mood (MASQ:GDD) additionally onto the low positive affect factor would significantly improve model fit. Indeed, applying this modification significantly improved model fit within both samples. In these models, all indicators significantly loaded onto their respective factors (see Fig. 2; standardized loadings presented). Additionally, in each sample, the three latent factors demonstrated moderate correlations with one another indicating they may be subfactors on a second-order factor. When we ran this model, each first-order factor significantly loaded onto a second-order factor in each sample (see Fig. 3; standardized loadings presented). Accordingly, factor scores were computed for this second-order factor and subject to regression analyses with smoking characteristics.

Table 4.

Fit indices for comparative models of the set of manifest psychological scales

| Fit Index

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | S-B χ2 | P | Df | CFI | RMSEA | S-B χ2 Diff |

| Study Sample 1: College Students (N =288) | ||||||

| 1 | 331.60 | .0000 | 27 | .672 | .198 | – |

| 2 | 307.81 | .0000 | 26 | .696 | .194 | 20.54† |

| 3 | 167.12 | .0000 | 24 | .846 | .144 | 146.58† |

| 3-Refined | 39.45 | .0177 | 23 | .982 | .050 | 48.39† |

| Study Sample 2: Adult Daily Smokers (N =338) | ||||||

| 1 | 244.21 | .0000 | 27 | .741 | .154 | – |

| 2 | 233.68 | .0000 | 26 | .753 | .154 | 10.45** |

| 3 | 53.13 | .0006 | 24 | .965 | .060 | 176.21† |

| 3-Refined | 28.50 | .1975 | 23 | .993 | .027 | 20.05† |

1 Factor Model = ‘Maladjustment’ Factor; 2 Factor Model = ‘Internalizing’ and ‘Externalizing’ Factors; 3 Factor Model = ‘Low Positive Affect,’ ‘Negative Affect,’ and ‘Disinhibition’ Factors; 3-Refined =3 Factor Model with empirical modifications based on modification indices output (MASQ:GDD loads onto both ‘Positive Affect’ and ‘Negative Affect’ factors). S-B χ2 Satorra-Bentler model Chi-square goodness-of-fit statistic, P Satorra-Bentler model Chi-square p-value; df =model degrees of freedom; CFI comparative fit index, RMSEA root mean square error of approximation; S-B χ2 Diff=Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square difference test

p < .05,

p < .01,

p< .001

Fig. 2.

a. Best-fitting model of psychological symptom scales, factor loadings, and factor correlations in Study Sample 1: College Students (N=288). b. Best-fitting model of psychological symptom scales, factor loadings, and factor correlations in Study Sample 2: Adult Daily Smokers (N=338). SHS Subjective Happiness Scale, CESD:ANH Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression-Anhedonia Scale. MASQ Mood and Anxiety Symptom Scale, AD Anhedonic Depression Scale, GDD General Distress Depression Scale, GDA General Distress Anxious Scale, AA Anxious Arousal Scale, AQR:PA Aggression Questionnaire Revised-Physical Aggression Scale, ASRS Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale, AUDIT Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. All factor loadings and factor correlations are standardized. Error terms associated with each psychological scale are not shown *p<.05, **p<.01, †p<.001

Fig. 3.

a. Second-order factor model of psychological scales, factor loadings, and factor correlations in Study Sample 1: College Students (N=288). b. Second-order factor model of psychological scales, factor loadings, and factor correlations in Study Sample 2: Adult Daily Smokers (N=338). SHS Subjective Happiness Scale, CESD:ANH Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression-Anhedonia Scale, MASQ Mood and Anxiety Symptom Scale, AD Anhedonic Depression Scale, GDD General Distress Depression Scale, GDA General Distress Anxious Scale, AA Anxious Arousal Scale, AQR:PA Aggression Questionnaire Revised-Physical Aggression Scale, ASRS Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale, AUDIT Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. All factor loadings and factor correlations are standardized. Error terms associated with each psychological scale are not shown*<.05, **<.01, †<.001

Relations between Psychological Symptoms and Smoking Characteristics

Shown in Table 5, in the college students, the AUDIT significantly associated with ever smoke a cigarette and the ASRS, AUDIT, and disinhibition factor each significantly associated with smoke 100+ cigarettes in lifetime. The low positive and negative affect factors, their respective indicators, and the second-order general maladjustment factor did not associate with these smoking variables. All relations maintained significance after applying the Benjamini-Hochberg test.

Table 5.

Associations between manifest Psychological Scales, Latent Factor Scores, and Smoking Variables

| Psychological Predictors | Study sample 1: College students

|

Study sample 2: Adult daily smokers

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ever Smoke | Smoke 100 | Age Onset | Cigs/Day | FTND | Withdrawal | |

| Psychological Scales | OR | OR | β | β | β | B |

| SHS | 0.88 | 1.14 | .03 | −.12* | −.03 | −.06 |

| CESD:ANH | 0.97 | 0.88 | −.03 | .11* | .10 | .09 |

| MASQ:AD | 1.06 | 1.00 | .07 | .13* | .01 | .12* |

| MASQ:GDD | 0.91 | 0.94 | .10 | .12* | −.01 | .21†a |

| MASQ:GDA | 0.91 | 1.02 | .13* | .12* | −.00 | .30†a |

| MASQ:AA | 1.00 | 1.20 | .08 | .13* | .06 | . 28†a |

| AQR:PA | 1.08 | 1.38 | −.01 | .05 | .03 | .04 |

| ASRS | 1.15 | 1.65**a | .03 | −.07 | −.10 | .15* |

| AUDIT | 2.23†a | 2.72†a | −.07 | −.18* | −.08 | −.03 |

| Factor Scores | ||||||

| Low Positive Affect | −1.03 | −0.96 | .04 | .14** | .03 | .12*a |

| Negative Affect | 0.93 | 1.08 | .12* | .12* | −.00 | . 29†a |

| Disinhibition | 1.17 | 1.70**a | .06 | .05 | −.04 | . 23†a |

| General Maladjustment | 0.97 | 1.13 | .08 | .09 | −.02 | . 26†a |

N=288 in Study Sample 1: College Students; N=338 in Study Sample 2: Adult Daily Smokers. SHS Subjective Happiness Scale, CESD:ANH Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression-Anhedonia Scale, MASQ Mood and Anxiety Symptom Scale: AD Anhedonic Depression Scale, GDA General Distress Anxious Scale, AA Anxious Arousal Scale, AQR:PA Aggression Questionnaire Revised-Physical Aggression Scale, ASRS Adult ADHD Self-report Scale, AUDIT Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Ever Smoke =ever smoked a cigarette (yes/no); Smoke 100 =Smoked 100 cigarettes in lifetime (yes/no); Age Onset =age first started smoking; Cigs/Day =average number of cigarettes per day; FTND Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence; Withdrawal =composite withdrawal symptom severity in most recent quit attempt. β =standardized betas. OR =standardized odds ratios. All models are adjusted for age, gender, and race. Significant findings at p <.05 are in bold

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Remained significant after applying the Benjamini-Hochberg test

In the adult smokers, cigarettes per day positively associated with the CESD:ANH, all MASQ subscales, the low positive affect and negative affect factors, and inversely with the SHS and AUDIT. Past withdrawal symptom severity associated with all MASQ subscales, the ASRS, all three first-order factors, and the second-order factor of general maladjustment. Age of regular smoking onset associated (positively) with the MASQ:GDA and the negative affect factor. Nicotine dependence severity did not associate with any of the manifest scales or latent factors. After adjusting for multiple tests, most of the relations with past withdrawal symptom severity maintained significance; however, all relations with cigarettes per day and age of smoking onset reduced below significance.

Discussion

Identifying a Structural Model of Psychological Symptoms

Of the structural models tested, the 3-factor model reflecting deficient positive affectivity, negative affectivity, and disinhibition, provided the best fit for the data in both samples. The replication of this model across two diverse samples suggests that it is less likely that these results were dependent on a specific sample. This is in contrast to our hypothesis that a 2-factor internalizing-externalizing model would be supported. This 3-factor model does not directly cohere with DSM-based syndrome conceptualizations as two distinct symptom manifestations of the same DSM-based syndrome (i.e., unipolar depression) loaded onto separate factors of [low] positive and negative affect. The make-up of this 3-factor model highlights the significance of within-disorder heterogeneity and supports approaches that do not solely rely on nosologically-based syndrome measures, which combine heterogeneous manifestations of psychological symptoms.

This model is largely consistent with Clark’s (2005) proposed 3-factor model of personality and psychopathology, which suggests that three latent factors representing innate biobehavioral temperament systems account for variation across diverse combinations of personality and psychopathology. In this model, positive affectivity refers to a person’s tendency to experience a wide range of positive emotions, reflects the strength of a behavioral approach system aimed at obtaining reward, and inversely associates with depression (Clark 2005). The positive affect factor yielded in this study is consistent with this conceptualization as it had loadings from several measures of happiness and anhedonia. However, the general depressive symptom scale (MASQ:GDD) also cross-loaded onto this factor, although with relatively lower loadings compared to the other indicators. This suggests that the low positive affect factor primarily reflected diminished appetitive drive but may also encompass certain aspects of distress. Indeed, studies have found that the behavioral approach system may be linked to certain low-arousal distress items that are found on this general depressive symptom scale (e.g., sadness, feelings of failure, and discouragement; Carver 2004; Higgins, Shah, and Friedman 1997). The second factor, negative affect, reflects the tendency to experience a diverse range of aversive emotional states, reflects the strength of a behavioral avoidance system aimed at avoiding threat, and underlies a broad range of psychopathology (Clark 2005). Negative affect has been proposed as a shared component of anxiety and depression (Clark and Watson 1991). Consistent with this, the scales that loaded onto this factor were measures of depressive and anxious symptoms. The third factor, disinhibition, is defined as a person’s lack of restraint in response to incoming stimuli (Clark 2005) and underlies the externalizing disorders (e.g., disruptive behavior and substance use disorders; Krueger 1999; Lynam et al. 2003; Vollebergh et al. 2001). Unsurprisingly, measures of hyperactivity-impulsivity, alcohol misuse, and physical aggression loaded onto this factor, each of which may characterize expressions of poor behavioral control.

Results also demonstrated that these three latent first-order factors significantly loaded on a second-order factor representing their shared variance. The second-order factor, referred to as general maladjustment, likely represents broad constructs such as overall severity of psychological symptoms. This second-order model coheres with the hypothesis that three levels of features best describe the generality and specificity of different types of psychological dysfunction: 1) narrowband-specific features, which differentiate each of the manifest scales from each other, 2) broadband-specific features (low positive affect, negative affect, and disinhibition in the current models), which distinguish broadband clusters from each other but that are shared among the manifest scales within each cluster, and 3) common features (second-order general maladjustment factor in the current model), which are found in nearly all types of psychological dysfunction (Ingram and Kendall 1987; Weiss et al. 1998). In line with this finding, recent genetic and confirmatory factor analytic studies have found evidence for a general maladjustment-like factor, in addition to internalizing and externalizing factors, across several different forms of psychopathology (Lahey et al. 2013; Lahey, Van Hulle, Singh, Waldman, and Rathouz 2011).

Relations between Psychological Symptoms and Smoking Characteristics

In support of our hypothesis, there were similar patterns of associations with smoking variables across manifest scales and latent factors of psychological symptoms. In the college students, only alcohol use disorder symptoms associated with ever smoking whereas a broader range of psychological symptoms, including ADHD symptoms, alcohol use disorder symptoms, and latent disinhibition, associated with established smoking (100+ cigs). Many studies have found a strong link between smoking and drinking in college students (Nichter, Nichter, Carkoglu, Lloyd-Richardson, and Tern 2010; Weitzman and Chen 2005), which could be accounted for by associating with substance using peers (Lynskey, Fergusson, and Horwood 1998) and being in substance use situations (Nichter et al. 2010). Prior research has also shown associations between a number of different disruptive behavior and substance use disorders and markers of established smoking (Burt, Dinh, Peterson, and Sarason 2000; Kollins et al. 2005; McMahon 1999; Rohde et al. 2003). Thus, while many college students may experiment with cigarette smoking, particularly in combination with alcohol use, these results illustrate that a smaller portion reported established smoking and indicate that impulse control features shared across a broad range of disinhibitory dysfunction may increase risk for this more established pattern of smoking.

In the adult daily smoker sample, each of the manifest scales on the low positive affect and negative affect factors significantly associated with cigarettes per day. Potentially, this finding indicates that individuals smoke at heavier levels to offset their affective disturbances (Carmody 1992; Pomerleau and Pomerleau 1984) or that continued, heavy tobacco smoking may lead to exacerbations in low positive affect and negative affect (Breslau, Peterson, Schultz, Chilcoat, and Andreski 1998). Generally, these results suggest that shared features of low positive affect and negative affect may largely account for many of the associations found between different manifestations of psychological dysfunction and heavier smoking (Greenberg et al. 2012; Johnson, Stewart, Zvolensky, and Steeves 2009; Kenney and Holahan 2008; Kollins et al. 2005; Lasser et al. 2000). However, because these relations dropped below significance after adjusting for multiple tests, future research is needed to confirm these results. Also in this sample, most of the scales on the low positive affect and negative affect factors, the ADHD symptom scale, each of the first-order latent factors (low positive affect, negative affect, disinhibition), and the second-order general maladjustment factor robustly associated with more severe retrospective withdrawal symptoms. Hence, this pattern of findings may suggest that variation in overall severity of psychological symptoms, rather than individual differences in type or quality of psychological symptoms, primarily explains relations found across many different types of manifest psychological dysfunction and nicotine withdrawal (Ameringer and Leventhal 2010; McClernon et al. 2011; Pomerleau, Marks, and Pomerleau 2000; Weinberger, Desai, and McKee 2010).

The results also revealed several unexpected findings in the adult smokers. First, alcohol use disorder symptoms inversely associated with cigarettes per day. This is surprising given the strong association documented between smoking and alcohol use (Dani and Harris 2005). Potentially, this finding captures heavy drinking, social smokers, who smoke mainly when drinking but have lighter patterns of daily smoking (King and Epstein 2005) compared to heavy smokers who likely smoke more evenly day-by-day (Krukowski, Solomon, and Naud 2005). However, because this sample had low alcohol use, it is unknown how these results will generalize to heavier levels of alcohol use. Second, the general anxiety symptom scale and latent negative affect factor associated with a later age of smoking onset. Similarly, a prior study found that children with anxiety disorders, controlling for comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders (e.g., ADHD, depression), had a later age of smoking onset (Costello, Erkanli, Federman, and Angold 1999). Because individuals with anxiety-spectrum pathology are more likely to have higher levels of trait harm avoidance (Starcevic, Uhlenhuth, Fallon, and Pathak 1996), this may reduce risk for early age of smoking onset. However, due to the retrospective nature of this measure, longitudinal research is needed to better examine this relation. Third, none of the psychological scales or latent factors associated with nicotine dependence severity. Potentially, this is because only individuals who smoked ten or more cigarettes per day were included in this study. Past research has found that risk for nicotine dependence increases most significantly from less than one to ten cigarettes per day and is minimal at levels higher than ten cigarettes per day (Kandel and Chen 2000). Thus, lower levels of smoking may be needed to show relations between psychological symptoms and variation in nicotine dependence.

In both samples, these results illustrated that the latent factors of low positive affect, negative affect, and disinhibition associated with smoking characteristics in a similar manner as their respective individual manifest psychological symptom indicators. Hence, accounting for shared psychological features in smoking relations may provide a more parsimonious model of the relation between diverse forms of psychological dysfunction and smoking. These results also provide insight into etiological processes underlying the link between psychological symptoms and smoking. That is, common factors that could be reflective of biobehavioral temperament systems (e.g., genetic risk factors or disrupted emotional processes; Watson, Gamez, and Simms 2005), which increase vulnerability to different forms of manifest psychological symptoms (Clark 2005), may directly relate to smoking. Therefore, integrating transdiagnostic treatment approaches that focus on core, underlying processes in conjunction with traditional smoking prevention and cessation programs may be effective and efficient for individuals with underlying psychological deficiencies. For example, cessation interventions for adult smokers that focus on increasing the ability to tolerate negative affect states and reducing avoidance or escape of aversive internal states (e.g., acceptance and commitment therapy; Brown et al. 2008, Hayes et al. 1999) or that focus on increasing pleasant non-smoking activities and enhancing pleasurable reward from non-smoking reinforcers (e.g., behavioral activation therapy; Jacobson et al. 1996; MacPherson et al. 2010) may be useful for different manifest syndromes comprised of low positive and high negative affect. Or, prevention interventions that focus on increasing behavioral inhibition through practice and training on inhibitory control tasks (Berkman, Graham, and Fisher 2012; Dowsett and Livesey 2000) may help to address the association found between established smoking and different manifest externalizing syndromes in young adults.

Limitations and Conclusions

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting these results. First, the psychological symptoms scales were chosen because they reflect expressions of common psychiatric disorders or their underlying traits (Babor, Biddle-Higgins, Saunders, and Monteiro 2001; Brown, Chorpita, and Barlow 1998; Fossati et al. 2007; Gehricke and Shapiro 2000; Kessler et al. 2005a; Kessler et al. 2005b; Mineka, Watson, and Clark 1998) and have shown relations with smoking (Audrain-McGovern et al. 2006; Kollins et al. 2005; Lasser et al. 2000; Lepper 1998; Leventhal et al. 2008; Nabi et al. 2010). However, many different types (e.g., cognitive, personality, and psychotic disorders), levels, and measures of psychological symptoms could have been included, which may have changed the structure of the model and subsequent results. Importantly, the scales used do not reflect psychiatric disorder status; rather, they reflect variation on the continuum of psychological functioning. Furthermore, the severity of psychological symptoms was relatively low in both samples and individuals who were currently on psychiatric medications or who met criteria for current mood disorder or substance dependence were excluded in the adult daily smoker sample, which could have influenced the magnitude and pattern of relations. Therefore, based on the measurement approach and sample characteristics, conclusions based on the current data are most relevant to low to moderate levels of psychological symptoms. However, past research shows relations between psychological symptoms and smoking at very low levels (e.g., >1 ADHD symptom, Elkins et al. 2007; >2 depressive symptoms, Niaura et al. 2001) and in individuals that do not have the respective current psychiatric disorder (Heffner, Johnson, Blom, and Anthenelli 2010; Leventhal et al. 2008); therefore, these results may generalize to a restricted but clinically important range of the spectrum of psychological functioning.

Second, important differences in demographics, clinical characteristics, and smoking measures (construct assessed and psychometric properties) between the two samples suggest that caution is warranted in making direct comparisons of results across the two samples. Although both samples were included to examine generalizability of the model, replicability of results, and relations across different smoking variables, future longitudinal research on the same sample is important to examine whether different psychological symptoms uniquely influence different stages of the tobacco dependence process. Third, because structural models of psychological symptoms have largely not been incorporated into the smoking literature, conclusions were based on a significance level of p<.05 to provide a broad picture of the patterns of relations between shared latent psychological dimensions, manifest psychological scales, and smoking using this type of analysis. Therefore, findings are subject to Type I error due to the multiple outcomes assessed. In particular, results that did not maintain significance after applying a Benjamini-Hochberg test should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, the effect sizes of many of these results were small, indicating that other, unmeasured factors accounted for much of the variance in the outcomes. Fourth, all measures in this study were self-report and therefore subject to several biases (e.g., recall, social desirability, self-awareness). Fifth, the cross-sectional design of this study does not allow for causal or temporal conclusions of relations between the psychological measures and smoking characteristics. Last, sample sizes for both studies were relatively small, particularly for structural equation modeling, therefore research incorporating larger sample sizes is needed to validate these results.

Despite these limitations, this study is one of the first to examine how a structural model of psychological dysfunction may address the issues psychological comorbidity creates for interpreting relations between psychological symptoms and smoking. Furthermore, this study is unique by incorporating a range of symptom- and syndrome-specific scales and by including two diverse samples. These results further support the notion that core, underlying dimensions likely account for psychological comorbidity, demonstrate that these dimensions may be present across demographically diverse samples, and suggest that latent, shared features of psychological symptoms may play an important role in relations across different manifestations of psychological dysfunction and smoking.

Acknowledgments

Funding This research was supported by National Institute of Health grants T32-CA009492 and R01-DA026831

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Experiment Participants All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committe and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- Allison PD. Missing data techniques for structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112(4):545–557. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameringer KJ, Leventhal AM. Symptom dimensions of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and nicotine withdrawal symptoms. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2010 doi: 10.1080/10550887.2012.735568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Tercyak KP, Neuner G, Moss HB. The impact of self-control indices on peer smoking and adolescent smoking progression. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2006;31(2):139–151. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Biddle-Higgins JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Health Care. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological) 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman ET, Graham AM, Fisher PA. Training self-control: a domain-general translational neuroscience approach. Child Development Perspectives. 2012;6(4):374–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borders A, Earleywine M, Jajodia A. Could mindfulness decrease anger, hostility, and aggression by decreasing rumination? Aggressive Behavior. 2010;36(1):28–44. doi: 10.1002/Ab.20327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Novak SP, Kessler RC. Psychiatric disorders and stages of smoking. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;55(1):69–76. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00317-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Peterson EL, Schultz LR, Chilcoat HD, Andreski P. Major depression and stages of smokingA longitudinal investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(2):161–166. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Palm KM, Strong DR, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Zvolensky MJ, Gifford EV. Distress tolerance treatment for early-lapse smokers: rationale, program description, and preliminary findings. Behavior Modification. 2008;32(3):302–332. doi: 10.1177/0145445507309024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Barlow DH. A proposal for a dimensional classification system based on the shared features of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: implications for assessment and treatment. Psychologicalal Assessment. 2009;21(3):256–271. doi: 10.1037/A0016608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. Structural relationships among dimensions of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders and dimensions of negative affect, positive affect, and autonomic arousal. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107(2):179–192. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.107.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant FB, Smith BD. Refining the architecture of aggression: a measurement model for the buss-perry aggression questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality. 2001;35(2):138–167. doi: 10.1006/jrpe.2000.2302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burt RD, Dinh KT, Peterson AV, Sarason IG. Predicting adolescent smoking: a prospective study of personality variables. Preventive Medicine. 2000;30(2):115–125. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmody TP. Affect regulation, nicotine addiction, and smoking cessation. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 1992;24(2):111–122. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1992.10471632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS. Negative affects deriving from the behavioral approach system. Emotion. 2004;4(1):3–22. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.4.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou CP, Bentler PM, Satorra A. Scaled test statistics and robust standard errors for non-normal data in covariance structure analysis: a Monte Carlo study. The British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 1991;44(Pt 2):347–357. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8317.1991.tb00966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA. Temperament as a unifying basis for personality and psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114(4):505–521. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.114.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100(3):316–336. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D, Reynolds S. Diagnosis and classification of psychopathology - challenges to the current system and future-directions. Annual Review of Psychology. 1995;46:121–153. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.46.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove VE, Rhee SH, Gelhorn HL, Boeldt D, Corley RC, Ehringer MA, Hewitt JK. Structure and etiology of co-occurring internalizing and externalizing disorders in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39(1):109–123. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9444-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Federman E, Angold A. Development of psychiatric comorbidity with substance abuse in adolescents: effects of timing and sex. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28(3):298–311. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani JA, Harris RA. Nicotine addiction and comorbidity with alcohol abuse and mental illness. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8(11):1465–1470. doi: 10.1038/nn1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran N, Spring B, McChargue D, Pergadia M, Richmond M. Impulsivity and smoking relapse. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6(4):641–647. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001727939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowsett SM, Livesey DJ. The development of inhibitory control in preschool children: effects of “executive skills” training. Developmental Psychobiology. 2000;36(2):161–174. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2302(200003)36:2<161::aid-dev7>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins IJ, McGue M, Iacono WG. Prospective effects of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, and sex on adolescent substance use and abuse. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1145–1152. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders, research version, non-patient edition (SCID-I/NP) New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fossati A, Barratt ES, Borroni S, Villa D, Grazioli F, Maffei C. Impulsivity, aggressiveness, and DSM-IV personality disorders. Psychiatry Research. 2007;149(1–3):157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehricke JG, Loughlin SE, Whalen CK, Potkin SG, Fallon JH, Jamner LD, Leslie FM. Smoking to self-medicate attentional and emotional dysfunctions. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9(Suppl 4):S523–S536. doi: 10.1080/14622200701685039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehricke J, Shapiro D. Reduced facial expression and social context in major depression: discrepancies between facial muscle activity and self-reported emotion. Psychiatry Research. 2000;95(2):157–167. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(00)00168-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerevich J, Bacskai E, Czobor P. The generalizability of the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2007;16(3):124–136. doi: 10.1002/Mpr.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JB, Ameringer KJ, Trujillo MA, Sun P, Sussman S, Brightman M, Leventhal AM. Associations between posttraumatic stress disorder symptom clusters and cigarette smoking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(1):89–98. doi: 10.1037/A0024328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: an experiential approach to behavior change. New York: The Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom tolerance questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner JL, Johnson CS, Blom TJ, Anthenelli RM. Relationship between cigarette smoking and childhood symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity in alcohol-dependent adults without attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12(3):243–250. doi: 10.1093/Ntr/Ntp200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET, Shah J, Friedman R. Emotional responses to goal attainment: strength of regulatory focus as moderator. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72(3):515–525. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.3.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling-a Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram RE, Kendall PC. The Cognitive Side of Anxiety. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1987;11(5):523–536. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Dobson KS, Truax PA, Addis ME, Koerner K, Gollan JK, Prince SE. A component analysis of cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(2):295–304. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KA, Stewart SH, Zvolensky MJ, Steeves D. Evaluating the mediating role of coping-based smoking motives among treatment-seeking adult smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11(11):1296–1303. doi: 10.1093/Ntr/Ntp134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Chen K. Extent of smoking and nicotine dependence in the United States: 1991–1993. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2000;2(3):263–274. doi: 10.1080/14622200050147538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney BA, Holahan CJ. Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking in a college sample. Journal of American College Health. 2008;56(4):409–414. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.44.409-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M, Demler O, Faraone S, Hiripi E, Walters EE. The world health organization adult ADHD self-report scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychological Medicine. 2005a;35(2):245–256. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. (vol 62, pg 617, 2005) Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005b;62(7):709–709. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Epstein AM. Alcohol dose-dependent increases in smoking urge in light smokers. Alcoholism-Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29(4):547–552. doi: 10.1097/01.Alc.0000158839.65251.Fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollins SH, McClernon FJ, Fuemmeler BF. Association between smoking and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in a population-based sample of young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(10):1142–1147. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RE, Markon KE. Reinterpreting comorbidity: A model-based approach to understanding and classifying psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2006;2:111–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF. The structure of common mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56(10):921–926. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R. Personality traits are differentially linked to mental disorders: a multitrait-multidiagnosis study of an adolescent birth cohort. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105(3):299–312. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.105.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krukowski RA, Solomon LJ, Naud S. Triggers of heavier and lighter cigarette smoking in college students. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;28(4):335–345. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Applegate B, Hakes JK, Zald DH, Hariri AR, Rathouz RJ. Is there a general factor of prevalent psychopathlogy during adulthood? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;121(4):971–977. doi: 10.1037/a0028355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Van Hulle CA, Singh AL, Waldman ID, Rathouz PJ. Higher-order genetic and environmental structure of prevalent forms of child and adolescent psychopathology. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68(2):181–189. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: a population-based prevalence study. JAMA. 2000;284(20):2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepper HS. Use of other reports to validate subjective wellbeing measures. Social Indicators Research. 1998;44:367–369. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Japuntich SJ, Piper ME, Jorenby DE, Schlam TR, Baker TB. Isolating the role of psychologicalal dysfunction in smoking cessation: relations of personality and psy-chopathology to attaining cessation milestones. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(4):838–849. doi: 10.1037/a0028449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Ramsey SE, Brown RA, LaChance HR, Kahler CW. Dimensions of depressive symptoms and smoking cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10(3):507–517. doi: 10.1080/14622200801901971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Leukefeld C, Clayton RR. The contribution of personality to the overlap between antisocial behavior and substance use/misuse. Aggressive Behavior. 2003;29(4):316–331. doi: 10.1002/Ab.10073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lynskey MT, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. The origins of the correlations between tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis use during adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 1998;39(7):995–1005. doi: 10.1017/S0021963098002960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Lepper HS. A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validiation. Social Indicators Research. 1999;46:137–155g. [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson L, Tull MT, Matusiewicz AK, Rodman S, Strong DR, Kahler CW, Lejuez CW. Randomized controlled trial of behavioral activation smoking cessation treatment for smokers with elevated depressive symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78(1):55–61. doi: 10.1037/a0017939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClernon FJ, Van Voorhees EE, English J, Hallyburton M, Holdaway A, Kollins SH. Smoking withdrawal symptoms are more severe among smokers with ADHD and independent of ADHD symptom change: results from a 12-day contingency-managed abstinence trial. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2011;13(9):784–792. doi: 10.1093/Ntr/Ntr073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon RJ. Child and adolescent psychopathology as risk factors for smoking initiation: an overview. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1(Suppl):45–50. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineka S, Watson D, Clark LA. Comorbidity of anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Annual Review of Psychology. 1998;49:377–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 6. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nabi H, Hall M, Koskenvuo M, Singh-Manoux A, Oksanen T, Suominen S, Vahtera J. Psychologicalal and somatic symptoms of anxiety and risk of coronary heart disease: the health and social support prospective cohort study. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67(4):378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niaura R, Britt DM, Shadel WG, Goldstein M, Abrams D, Brown R. Symptoms of depression and survival experience among three samples of smokers trying to quit. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15(1):13–17. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichter M, Nichter M, Carkoglu A, Lloyd-Richardson E, Tern Smoking and drinking among college students: “It’s a package deal”. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;106(1):16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierucci-Lagha A, Gelernter J, Feinn R, Cubells JF, Pearson D, Pollastri A, Kranzler HR. Diagnostic reliability of the semi-structured assessment for drug dependence and alcoholism (SSADDA) Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;80(3):303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau CS, Marks JL, Pomerleau OF. Who gets what symptom? Effects of psychiatric cofactors and nicotine dependence on patterns of smoking withdrawal symptomatology. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2000;2(3):275–280. doi: 10.1080/14622200050147547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau CS, Zucker AN, Stewart AJ. Patterns of depressive symptomatology in women smokers, ex-smokers, and never-smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28(3):575–582. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00257-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau OF, Pomerleau CS. Neuroregulators and the reinforcement of smoking: towards a biobehavioral explanation. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 1984;8(4):503–513. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(84)90007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychologicalal Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Brown RA, Gau JM, Kahler CW. Psychiatric disorders, familial factors and cigarette smoking: IAssociations with smoking initiation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2003;5(1):85–98. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000070507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Incorporated. The SAS System for Windows (Version 9.2) Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. Corrects to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika. 2001;66(4):507–514. doi: 10.1007/Bf02296192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte-van Maaren YWM, Carlier IVE, Zitman FG, van Hemert AM, de Waal MWM, van Noorden MS, Giltay EJ. Reference values for generic instruments used in routine outcome monitoring: the leiden routine outcome monitoring study. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12 doi: 10.1186/1471-244x-12-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer AB. Meta-analysis of the factor structures of four depression questionnaires: Beck, CES-D, Hamilton, and Zung. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62(1):123–146. doi: 10.1002/Jclp.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade T, Watson D. The structure of common DSM-IV and ICD-10 mental disorders in the Australian general population. Psychol Med. 2006;36(11):1593–1600. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008452. doi:0.1017/S0033291706008452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starcevic V, Uhlenhuth EH, Fallon S, Pathak D. Personality dimensions in panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1996;37(2–3):75–79. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollebergh WA, Iedema J, Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Smit F, Ormel J. The structure and stability of common mental disorders: the NEMESIS study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(6):597–603. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Weber K, Assenheimer JS, Strauss ME, McCormick RA. Testing a tripartite model: II. Exploring the symptom structure of anxiety and depression in student, adult, and patient samples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995a;104(1):15–25. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Weber K, Assenheimer JS, Clark LA, Strauss ME, McCormick RA. Testing a tripartite model: I. Evaluating the convergent and discriminant validity of anxiety and depression symptom scales. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995b;104(1):3–14. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Gamez W, Simms LJ. Basic dimensions of temperament and their relation to anxiety and depression: a symptom-based perspective. Journal of Research in Personality. 2005;39(1):46–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2004.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Desai RA, McKee SA. Nicotine withdrawal in U.S. smokers with current mood, anxiety, alcohol use, and substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;108(1–2):7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B, Susser K, Catron T. Common and specific features of childhood psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107(1):118–127. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman ER, Chen YY. The co-occurrence of smoking and drinking among young adults in college: national survey results from the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;80(3):377–386. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]