Abstract

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) has been noted to fluctuate among children during hematopoietic stem cell transplant recovery (HSCT); however, the specific timing and associations of these changes is poorly understood. This repeated measures study aimed to describe health-related quality of life (HRQoL) changes among children and adolescents during the first six months of hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) recovery and estimate the associations of demographic factors, diagnosis, transplant information, and symptoms with HRQoL. Twenty-three children and adolescents receiving from an allogeneic HSCT were recruited from a pediatric teaching institution in the southern United States. Demographic, diagnosis, and transplant information was obtained from the medical record. The Memorial Symptom Assessment questionnaire and the Peds Quality of Life Cancer Module (PedsQL CM™) were completed at one month post HSCT then once monthly for five additional months. Mean HRQoL scores fluctuated during the study with the lowest mean HRQoL noted at one month post HSCT and the highest mean HRQoL noted at four months post HSCT. No significant differences in HRQoL scores were noted among demographic, diagnosis, or transplant factors. Presence of feeling tired, sad, worried, or having insomnia at one month post HSCT was negatively correlated to HRQoL. Nurses have opportunities to explore important issues with patients and need to be aware of fluctuations with HRQoL and factors associated with lower HRQoL during HSCT recovery.

Keywords: Quality of life, HSCT, pediatric, adolescent, symptom

Approximately 2500 children in the U.S. under 20 years of age undergo hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) each year for the treatment of malignant diseases and 65% of these children receive an allogeneic HSCT (Pasquini & Wang, 2013). Allogeneic HSCTs pose higher risks for complications due to the intensity of the conditioning regimen, graft type, and prolonged duration of immunosuppression (Munchel, Chen, & Symons, 2011). Complications from allogeneic HSCT include infection, graft-versus-host disease, and organ dysfunction or damage (Munchel, Chen, & Symons, 2011). Despite these complications, pediatric survival rates have significantly improved due to advances in therapy and supportive care (Packman, Weber, Wallace, & Bugescu, 2010). Patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT demonstrate five- and 10-year overall survival rates of 89% and 85%, respectively (Wingard et al., 2011). Given this success, HSCT research has shifted from solely survivorship to preserving the highest cure rates with the least toxicity and adverse late effects (Masera, Chesler, Zebrack, & D’Angio, 2013; Eiser & Varni, 2013). One outcome to receive increased attention has been health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Measuring HRQoL among HSCT patients provides insight into the impact of the illness and treatment on the patient’s life. HRQoL is a multidimensional concept that encompasses the physical, psychological, and social components of an individual’s life in relation to their disease and treatment (Strand & Russell, 1997).

Background and Significance

HSCT involves a toxic treatment regimen of total body irradiation and/or high dose chemotherapy followed by hematopoietic stem cell rescue (autologous) or hematopoietic stem cell transplant (allogeneic). Patients are hospitalized for approximately 20–30 days after HSCT to await hematopoietic reconstitution and receive care for complications and side effects; however, patients experience multiple symptoms and complications for months beyond the initial hospitalization. Full recovery can take six to twelve months following HSCT. During this time, patients manage numerous medications, adhere to strict infection precaution measures, and attend multiple medical appointments. The combination of these factors may affect the patient’s quality of life.

Four recent systematic reviews have reported that HRQoL is poor in children undergoing HSCT, shows no improvement for several months, and does not return to baseline until one to three years post-HSCT (Clarke, Eiser, & Skinner, 2008; Tremolada et al., 2009; Packman et al., 2010; Tanzi, 2011). Two studies among children showed poor HRQoL scores immediately following HSCT without significant improvement 3 months later (Brice et al., 2013; Rodday, et al., 2013). One study evaluated HRQoL at 3, 6, and 12 months post autologous or allogeneic HSCT among 160 pediatric patients and found the lowest HRQoL reports occurring at 3 months post HSCT (Parsons et al., 2006). Quality of life improves in children after 3 months post HSCT (Felder-Puig et al., 2006; Barrera et al., 2000); however, the specific variations of HRQoL during HSCT recovery is poorly understood because studies often allow months to elapse before re-evaluation. The variability of HRQoL during individual months post HSCT has not been evaluated.

Poor HRQoL among pediatric HSCT patients have been examined among several contexts but inconclusively linked to demographic or clinical factors. Girls have reported lower HRQoL scores than boys during HSCT recovery (Brice et al., 2013; Tremolada et al., 2009; Kanellopoulos et al, 2013), although a systematic review reported that gender’s effect on HRQoL was likely non-significant (Packman et al., 2010). African American children reported higher HRQoL scores than Hispanic, Caucasian or Asian American children during the first year post HSCT in one study (Brice et al., 2013) but no differences were noted in another study (Oberg et al., 2013). During the first year following HSCT, children receiving an unrelated HSCT reported lower HRQoL scores than children receiving a related HSCT, likely due to the increased occurrence of comorbidities associated with unrelated HSCTs (Rodday et al., 2013; Packman et al., 2010; Leung et al., 2011). Although mismatched HSCTs have an increased risk of complications such as graft-versus-host disease (Munchel, Chen, & Symons, 2011), which could affect HRQoL, no study has evaluated if matched and mismatched HSCTs affect HRQoL differentially.

Pediatric patients recovering from HSCT can experience multiple symptoms during HSCT recovery that could affect HRQoL. Physical or psychological symptoms might increase the need for medical care and negatively affect a child’s quality of life (Kanellopoulos et al., 2013; Tanzi, 2011; Tremolada et al., 2009), but no study has evaluated specific symptoms in relationship to quality of life. Although lower HRQoL scores has been associated with generalized symptom severity in this population (Forinder, Lof, & Winiarski, 2005), the experiences of specific symptoms has not been examined in relation to quality of life.

This study is the first to longitudinally describe HRQoL by month among a single cohort of children who underwent allogeneic HSCT. The primary aim of this study was to describe the HRQoL changes over time of children and adolescents by month during the first six months post allogeneic HSCT. A secondary aim was to estimate the association between mean HRQoL and demographic information (age, gender, ethnicity), diagnosis, transplant factors (stem cell source and match), and individual symptom presence reported at 1 month post allogeneic HSCT.

Methods

Design, Setting, Sample

The study employed a repeated measures design. The sample was drawn from current patients in the HSCT service of a large children’s hospital in the southern United States. Eligibility criteria included patients age 7–18 years, self-reported ability to speak and read English, and engrafted from an allogeneic HSCT. Exclusion criteria included receipt of an autologous HSCT, a developmental delay, or participation in another symptom study. Of 27 patients and their legal guardians invited to participate in the study from June 2011 to December 2012, all legal guardians provided consent, but only 23 patients provided assent and were included in the study. The four patients who did not provide assent reported not wanting to answer questionnaires or talk about their symptoms. The study was approved by the institution’s Internal Review Board.

Measurements

Health-Related Quality of Life

The dependent variable, health-related quality of life, was measured using the Peds Quality of Life Cancer Module (PedsQL CM™), which has been designed for use among patients age 5–18 years. Patients rated 27 items on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating better HRQoL. Examples of items included ratings of how much pain, nausea, procedural anxiety, and perceived physical appearance bothered the patient. The PedsQL CM™ has demonstrated reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.72) and construct validity, including both a significant difference between healthy children and children with cancer at p < 0.001 using the known-groups method and a significant inter-correlation with the Multidimensional Fatigue Scale Total Score in a medium-to-large effect size range (Varni et al., 2002).

Demographic and Transplant Factors

The primary investigator reviewed the patient’s medical record to identify demographic, diagnosis, and HSCT information, which was documented in a de-identified spreadsheet. Demographic information included patients’ gender, ethnicity, and age in years. Diagnosis included notation of the disease for which the patient was receiving the HSCT. Transplant factors included noting if the transplant was matched or mismatched and from a related or unrelated donor.

Symptoms

Symptoms were assessed with one of two versions of the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS) validated for the respondent’s age. Children ages 13–18 years completed the MSAS 10–18, a modification of the original MSAS to a reading and comprehension age of 10 years. The MSAS 10–18 assesses the frequency, severity, and distress of 30 symptoms on a 4- or 5-point Likert scale, with good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha=0.83 for psychological symptoms, 0.87 for physical symptoms, and 0.85 for a global distress index) and validity (correlations with the pediatric memorial pain assessment card and face-valid visual analog scales at p<0.01) (Collins et al., 2000). Children ages 7–12 years completed the MSAS 7–12, which assesses the frequency, severity and distress of eight physical and psychological symptoms on a 3- or 4-point Likert scale. Space is provided on the form to allow children to write in additional symptoms, if they occurred. Adequate test-retest reliability (overall alpha coefficient=0.67) and validity (correlations between the visual analog scale scores for nausea, pain, and sadness and the corresponding MSAS symptom of r = 0.74, 0.70, and 0.76 respectively, p<0.01) has been noted (Collins et al., 2002).

Procedures

Approximately 30 days post-HSCT, the primary investigator introduced patients and their parent/legal guardian to the study during a routine clinic visit or while hospitalized. If the patient did not want to participate in the study, no further discussion occurred. Otherwise, study information was provided and the consent was reviewed. After questions were answered, the consent was obtained from the parent/legal guardian and assent from the patient, or consent from the patient if 18 years of age. Data collection occurred within 7 days of their first, second, third, fourth, fifth, and sixth month post-HSCT. At the first data collection, the primary investigator collected demographic, diagnosis, and transplant information from the medical record, while the patient completed self-reported questionnaires in the clinic or hospital room. The researcher returned to the patient’s room after approximately 15 minutes to answer any questions about the questionnaires, review the questionnaires for completeness, confirm whether missing data was intentional or accidently missed, and provide the patient with $5 as appreciation for study participation. If the patient did not want to complete the questionnaire at any data collection time during the study, the primary investigator asked if she could return in 30 days to ask for participation at that time. If the patient agreed, data was counted as missed; however, if he/she declined further contact, then the patient was withdrawn from the study. Patients were also withdrawn from the study if they experienced a disease relapse requiring further treatment or if the patient died.

Statistical Analysis

To address the first objective of HRQoL changes over time, descriptive statistics were used to examine HRQoL ratings at each time point. Changes of HRQoL ratings over time were evaluated with repeated measures ANOVA. To address the second objective of the association of HRQoL with independent fixed variables of age, gender, ethnicity, diagnosis, HSCT source, and HSCT match were re-scaled as dichotomous variables and evaluated as binary classification variables with HRQoL in serial t-tests. Finally, the eight individual symptoms common to both the MSAS 7–12 and 10–18 questionnaires (tired, sad, itchy, worry, pain, difficulty eating, vomiting, and insomnia) were re-scaled as present/absent at 1 month post-HSCT and compared to HRQoL, using Pearson correlation. HRQoL was plotted separately within the present and absent symptom groups during the subsequent months 2–6 for descriptive purposes only; further statistical tests were not conducted due to the decreasing sample size over time. Significance was declared at an a priori value of 0.05. All analyses were conducted using SAS v9.3.

Results

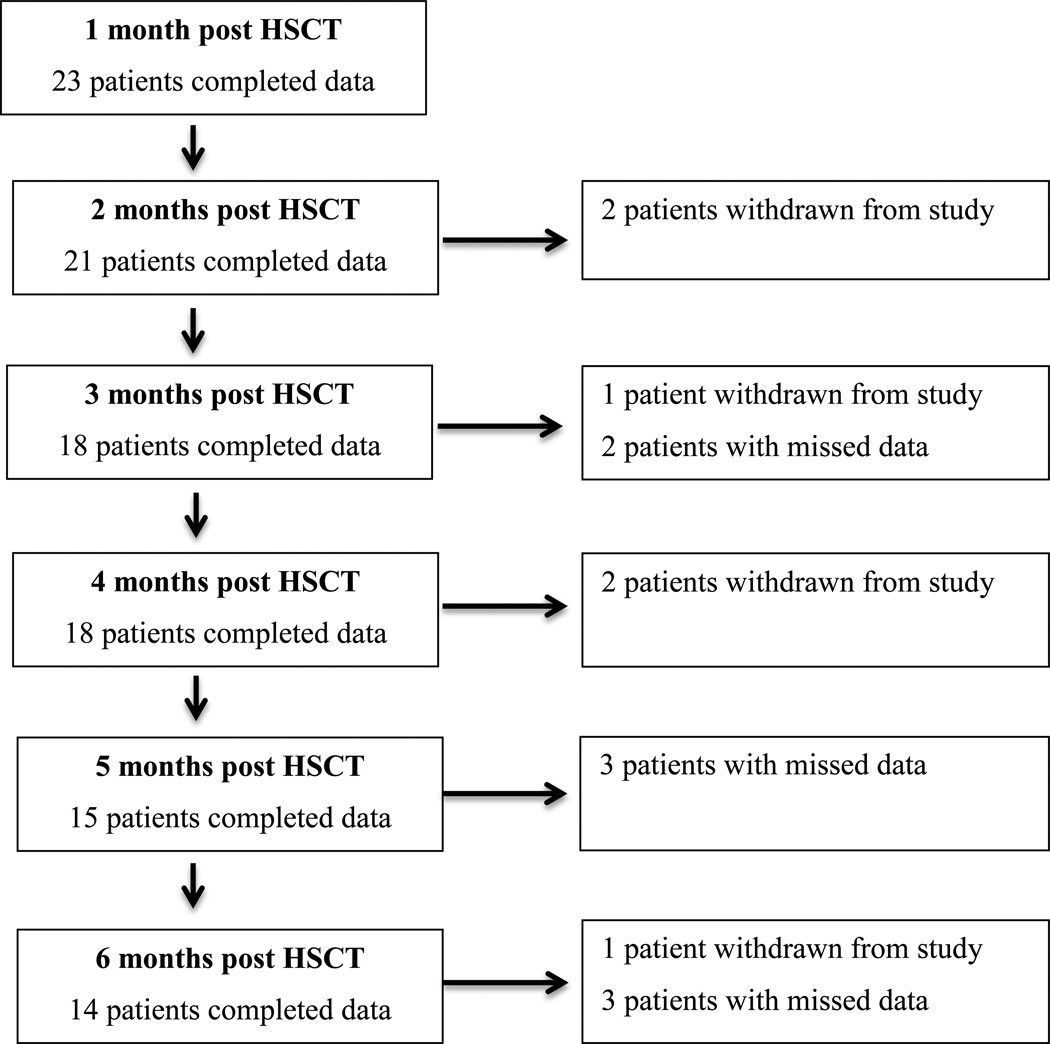

Characteristics of the sample (N=23) are presented within Table 1. A majority of the sample was male; Hispanic; between the ages of 7 to 12 years; diagnosed with a malignant disease (leukemia, lymphoma, or myelodysplastic syndrome); and recipient of a matched related or matched unrelated product. Six patients were withdrawn from the study over time; two patients died, two relapsed, and two voluntarily withdrew from the study. Incomplete data collection at other times were due to missed follow up appointments or patients not wanting to complete the questionnaires at that specific time point. See Figure 1 for a synopsis of data collection. Participants with missing data ranged in age from 7 to 18 years; were diagnosed with a variety of diseases, although the majority had a malignant disease; were primarily Hispanic; and were primarily a recipient of a matched related or matched unrelated product.

Table 1.

Mean HRQoL Scores According to Demographic/Transplant Factors (N=23)

| 1 month post HSCT |

2 months post HSCT |

3 months post HSCT |

4 months post HSCT |

5 months post HSCT |

6 months post HSCT |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGE | ||||||

| Age 7–12 years (n=14) | 79.2 | 85.9 | 86.8 | 90.9 | 90.9 | 89.9 |

| Age 13–18 years (n=9) | 67.1 | 80.1 | 77.1 | 84.4 | 80.1 | 79.2 |

| Significance | 0.13 | 0.30 | 0.11 | 0.23 | 0.12 | 0.22 |

| ETHNICITY | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic (n=13) | 77.4 | 85.6 | 83.1 | 87.9 | 87.1 | 87.5 |

| Hispanic (n=10) | 70.6 | 81.6 | 81.9 | 88.6 | 85.7 | 80.6 |

| Significance | 0.40 | 0.46 | 0.84 | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.44 |

| GENDER | ||||||

| Male (n=15) | 74.3 | 82.7 | 82.9 | 87.9 | 86.4 | 84.0 |

| Female (n=8) | 74.7 | 85.7 | 81.5 | 88.7 | 86.7 | 85.9 |

| Significance | 0.96 | 0.60 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.97 | 0.85 |

| DIAGNOSIS | ||||||

| Malignant (n=16) | 70.5 | 82.1 | 82.3 | 87.6 | 86.1 | 82.6 |

| Non-malignant (n=7) | 83.3 | 86.9 | 83.0 | 89.2 | 87.5 | 89.4 |

| Significance | 0.13 | 0.41 | 0.91 | 0.78 | 0.86 | 0.49 |

| HSCT SOURCE | ||||||

| Related (n=12) | 73.5 | 86.9 | 84.5 | 91.2 | 89.0 | 87.7 |

| Unrelated (n=11) | 75.4 | 80.7 | 81.2 | 86.1 | 84.9 | 82.2 |

| Significance | 0.81 | 0.25 | 0.60 | 0.34 | 0.57 | 0.54 |

| HSCT MATCH | ||||||

| Match (n=13) | 75.6 | 84.3 | 84.6 | 88.9 | 87.4 | 85.2 |

| Mismatch (n=10) | 72.9 | 82.7 | 78.2 | 86.6 | 84.1 | 81.9 |

| Significance | 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.32 | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.76 |

Figure 1.

Subject Retention

Health-related quality of life trajectory

Mean HRQoL scores fluctuated during the six months post HSCT (Figure 2), and no statistically significant difference was noted over time (p=0.31). Mean HRQoL was lowest at one month post-HSCT (74.43, SD 18.44) and highest at four months post-HSCT (88.19, SD 10.71). Mean HRQoL scores declined from months 2 to 3, months 4 to 5, and months 5 to 6.

Figure 2.

Overall Mean HRQoL Scores Over Time

Demographic/Transplant Factors and HRQoL

No statistically significant differences in HRQoL scores were noted between any demographic groups at any time point (Table 1). In addition, HRQoL scores were similar among participants regardless of diagnosis, transplant source, and transplant match (Table 1).

Symptoms and HRQoL

Of the eight symptoms assessed at one month post-HCST (tired, sad, itchy, pain, worry, difficulty eating, vomiting, and insomnia), ‘worry’ was the least often reported (n=7), and ‘vomiting’ was the most frequently reported (n=18) at one month post-HSCT. All symptoms except feeling itchy were inversely related to mean HRQoL scores at one month post-HSCT (Table 2), representing lower HRQoL among patients who reported a symptom of tired, sad, pain, worry, difficulty eating, vomiting, or insomnia versus patients who did not have the symptom at one month post-HSCT. Four of the negative correlations were statistically significant (feeling tired, sad, worried, and having insomnia). Furthermore, when each of the statistically significant symptoms (feeling tired, sad, worried, or having insomnia) were present at one month post HSCT, a lower HRQoL score was noted in the subsequent five months post HSCT when compared to individuals without the symptom at one month post HSCT (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Correlation of mean HRQoL scores with Symptoms at One Month post HSCT (N=23)

| Tired | Sad | Itchy | Pain | Worry | Difficulty Eating |

Vomiting | Insomnia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRQoL score | −0.6746 | −0.4921 | 0.0086 | −0.2019 | −0.5368 | −0.3060 | −0.2756 | −0.6033 |

| Significance | 0.0004 | 0.0171 | 0.9690 | 0.3557 | 0.0083 | 0.1556 | 0.2030 | 0.0023 |

Figure 3.

HRQoL Scores and Symptoms

Discussion

This study describes the trajectory of HRQoL scores as reported by children and adolescents and based on monthly assessments during the first six months post allogeneic HSCT. The current study suggests an overall moderate improvement in HRQoL scores between one and six months post-HSCT but illustrates variation of scores throughout the early HSCT recovery period. This variation is similar to findings by Brice et al. (2011) who state that although the majority of children experienced an improvement in HRQoL ratings during the first year post HSCT, there was a minority who experienced a decline in HRQoL. Felder-Puig and colleagues (2006) have also alluded to such a variable course of improvement, reporting that not all patients had a “favorable evolution” (p. 124) as some patients had setbacks during the first 6 months post HSCT. This discussion raises clinical concern as the variation in HRQoL has been alluded to in previous studies but not well described. Thus, children who are experiencing declines in quality of life may not be readily identified in the clinical setting. Findings from this study illustrate HRQoL changes over time and identify specific time points when children may be experiencing declines during HSCT recovery (2 to 3 months, 4 to 5 months, and 5 to 6 months post HSCT).

Although this study found no significant associations between HRQoL and demographic, disease or transplant factors, additional studies with a larger sample size should be conducted to further evaluate associations. Previous studies have shown mixed findings with HRQoL and demographic and disease associations (Packman et al., 2010; Oberg et al., 2013; Brice et al, 2013). Additional research should be performed to clarify the evaluation of these and additional factors that could be contributing to poor HRQoL during HSCT recovery. Body image issues are an important concern for many adolescents and have been thought to contribute to poor HRQoL post HSCT (Parsons et al., 2006). The prolonged isolation that is necessary for at least the first 100 days post HSCT while the patient has a compromised immune system may contribute to the lower HRQoL ratings (Packman et al., 2010). Reintegration to life outside of the medical center has also been noted as a factor affecting HRQoL as HSCT patients report concerns when rejoining their peer group (Packman et al., 2010). This may be reflected with the declining HRQoL ratings during months four to six post-HSCT, when patients are often returning home and back to school.

This study found that HSCT patients who report symptoms of being tired, sad, worried, or having insomnia at 1 month post-HSCT had lower HRQoL when compared to HSCT patients without those symptoms. Several systematic reviews of pediatric HSCT patients demonstrate an association between the presence of worry or depression and poor HRQoL (Tanzi, 2011; Clarke, Eiser, & Skinner, 2008; Packman et al., 2010). In addition, insomnia, fatigue, and anxiety have been linked to poor quality of life among 285 childhood leukemia and lymphoma survivors (Kanellopoulos et al., 2013). However, these studies fail to identify specific HRQoL trends among these symptomatic patients. This current study expands on symptom and HRQoL associations by identifying that when patients had symptoms of feeling tired, sad, worried, or insomnia at one month post-HSCT, their HRQoL does not recover to the level of non-symptomatic patients within six months. This trend should be evaluated with additional studies so that patients with specific symptoms can be identified early during HSCT recovery and targeted for supportive therapies.

There are several important limitations noted within this study. The small sample size from a single institution limits generalization to other pediatric HSCT patients and may have precluded finding a significant effect that actually does exist in this clinical population. Insufficiently represented in the data were patients who relapsed and/or died, who missed appointments for unknown reasons, and who did not want to complete the questionnaires, any or all of whom may have been systematically different with respect to their HRQoL and/or distressing symptoms from those who remained in the study. If their experiences were worse than those who remained, differences in scores might have more pronounced had they been included. A repeated measures study during this critical time should consider a larger sample size to take into account attrition and missing data noted in this study. In addition, a larger sample size would be needed to more robustly describe quality of life trajectories and correlations. Particularly needed are large pediatric HSCT studies to investigate potential associations between HRQoL and patient characteristics (i.e., cognitive development, gender, and disease) and external factors (social reintegration, family support, and communication style). Identification of these factors will help to identify vulnerable patients and enrich the development of strategies to assist them.

Nursing Implications

Nurses may expect that HRQoL fluctuates among children and adolescents during the first 6 months post HSCT. Nurses have unique opportunities to explore quality of life issues with their patients because of the relationship that develops during the patient’s frequent medical visits and extensive care (Zolnierek, 2014). This connection and mutual understanding allows the nurse to explore concerns and potential interventions with the patient to improve HRQoL.

Nurses require robust evidence of the specific characteristics and timing associations for patients’ HRQoL during HSCT recovery. By recognizing at-risk patients, nurses can promote methods to enhance coping. In addition, nurses can query patients during the time frame of greatest risk to determine HRQoL concerns that may be developing. Once these risk factors are better identified, targeted discussions and strategies can be employed to prevent the intermittent decreased HRQoL trends currently noted during HSCT recovery, and improve HRQoL for patients.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by an institutional training grant (K12CA090433) from the NIH-NCI.

Contributor Information

Cheryl Rodgers, Email: cheryl.rodgers@duke.edu, Duke University School of Nursing, 307 Trent Drive, Durham, NC 27710.

Patricia Wills-Bagnato, Email: pwbagnat@texaschildrens.org, Baylor College of Medicine, Director of Advance Practice Nurses, Texas Children’s Hematology and Cancer Centers, 6621 Fannin, Houston, TX 77030.

Richard Sloane, Email: richard.sloane@dm.duke.edu, Duke University, Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development, Box 3003 DUMC, Busse Building, Duke South, Durham, NC 27710.

Marilyn Hockenberry, Email: marilyn.hockenberry@duke.edu, Nursing and Professor of Pediatrics, Duke University School of Nursing, 307 Trent Drive, Durham, NC 27710.

References

- Barrera M, Boyd-Pringle LA, Sumbler K, Saunders F. Quality of life and behavioral adjustment after pediatric bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2000;26(4):427–435. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brice L, Weiss R, Wei Y, Satwani P, Bhatia M, George D, Sands SA. Health-related quality of life: The impact of medical and demographic variables upon pediatric recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2011;57:1179–1185. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke SA, Eiser C, Skinner R. Health-related quality of life in survivors of BMT for paediatric malignancy: A systematic review of the literature. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2008;42:73–82. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JJ, Byrnes ME, Dunkel IJ, Lapin J, Nadel T, Thaler HT, Portenoy RK. The measurement of symptoms in children with cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2000;19(5):363–377. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00127-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JJ, Devine TD, Dick GS, Johnson EA, Kilham HA, Pinkerton CR, Portenoy RK. The measurement of symptoms in young children with cancer: The validation of the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale in children aged 7–12. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2002;23(1):10–16. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00375-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiser C, Varni JW. Health-related quality of life and symptom reporting: Similarities and differences between children and their parents. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2013;172:1299–1304. doi: 10.1007/s00431-013-2049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felder-Puig R, di Gallo A, Waldenmair M, Norden P, Winter A, Gadner H, Topf R. Health-related quality of life of pediatric patients receiving allogeneic stem cell or bone marrow transplantation: results of a longitudinal, multi-center study. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2006;38(2):119–126. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forinder U, Lof C, Winiarski J. Quality of life and health in children following allogenic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2005;36(2):171–176. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanellopoulos A, Hamre HM, Dahl AA, Fossa SD, Ruud E. Factors associated with poor quality of life in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and lymphoma. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2013;60:849–855. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung W, Campana D, Yang J, Pei D, Coustan-Smith E, Gan K, Pui C. High success rate of hematopoietic cell transplantation regardless of donor source in children with very high-risk leukemia. Blood. 2011;118(2):223–230. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-333070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masera G, Chesler M, Zebrack B, D’Angio GJ. Cure is not enough: One slogan, two paradigms for pediatric oncology. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2013;60:1069–1070. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munchel A, Chen A, Symons H. Emergent complications in the pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant patient. Clinical Pediatric Emergency Medicine. 2011;12(3):233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.cpem.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberg JA, Bender JG, Morris E, Harrison L, Basch CE, Garvin JH, Cairo MS. Pediatric allo-SCT for malignant and non-malignant diseases: Impact on health-related quality of life outcomes. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2013;48:787–793. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packman W, Weber S, Wallace J, Bugescu N. Psychological effects of hematopoietic SCT on pediatric patients, siblings and parents: A review. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2010;45:1134–1146. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons SK, Shih MC, Duhamel KN, Ostroff J, Mayer D, Austin J, Manne S. Maternal perspectives on children’s health-related quality of life during the first year after pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2006;31(10):1100–1115. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquini MC, Wang Z. Current use and outcome of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: CIBMTR Summary Slides. 2013 Available at: http://www.cibmtr.org. [Google Scholar]

- Rodday AM, Terrin N, Parsons S the HSCT-CHESS Study. Measuring global health-related quality of life in children undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant: A longitudinal study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2013;11:26. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-11-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strand C, Russell S. WHO/ILAR taskforce on quality of life. Journal of Rheumatology. 1997;24(8):1630–1633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzi EM. Health-related quality of life of hematopoietic stem cell transplant childhood survivors: State of the science. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2011;28(4):191–202. doi: 10.1177/1043454211408100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremolada M, Bonichini S, Pillon M, Messina C, Carli M. Quality of life and psychosocial sequelae in children undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A review. Pediatric Transplantation. 2009;13:955–970. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2009.01203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingard JR, Majhail NS, Brazauskas R, Wang Z, Sobocinski KA, Jacobsohn D, Socie G. Long-term survival and late deaths after allogeneic hemoatpoietic cell transplantation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(16):2230–2239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.7212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Katz ER, Meeske K, Dickinson P. The PedsQL™ in pediatric cancer. Cancer. 2002;94(7):2090–2106. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolnierek CD. An integrative review of knowing the patient. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2014;46(1):3–10. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]