Abstract

The Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 requires commercial insurers providing group coverage for substance use disorder services to offer benefits for those services at a level equal to those for medical or surgical benefits. Unlike previous parity policies instituted for federal employees and in individual states, the law extends parity to out-of-network services. We conducted an interrupted time-series analysis using insurance claims from large self-insured employers to evaluate whether federal parity was associated with changes in out-of-network treatment for 525,620 users of substance use disorder services. Federal parity was associated with an increased probability of using out-of-network services, an increased average number of out-of-network outpatient visits, and increased average total spending on out-of-network services among users of those services. Our findings were broadly consistent with the contention of federal parity proponents that extending parity to out-of-network services would broaden access to substance use disorder care obtained outside of plan networks.

The Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008, which went into effect in 2010, requires private health insurance plans that offer coverage for mental health or substance use disorder services to cover those services on a par with medical or surgical services (the act is often referred to as “federal parity”). The act applies to employer-sponsored health insurance plans, Medicare Advantage coverage offered through a group health plan, Medicaid managed care, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and state and local government plans. In addition, all insurance products sold in the health insurance Marketplaces established by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) are now required to offer mental health and substance use disorder benefits in compliance with the requirements of the federal parity law.

Before 2010, private health plans imposed annual limits on inpatient days and outpatient visits and annual and lifetime dollar limits on mental health or substance use disorder benefits, and higher cost sharing for mental health and substance use disorder services than for medical and surgical services. These limits were imposed to address concerns that equal coverage of these services would lead to significant increases in service use and spending. As a result, insurance beneficiaries faced limits on the amount of reimbursed substance use disorder services and were subject to higher cost sharing for those services than for medical or surgical benefits.1 This finding raises concerns, given the poor rates of treatment for substance use disorders in the United States: Of the estimated 9 percent of the US population ages twelve and older with these disorders in 2009, only 19.1 percent received any treatment.2

Federal parity was preceded by other parity initiatives. These included state parity laws, many of which excluded substance use disorders or included a more restrictive benefit design for them than for mental health;3 the federal Mental Health Parity Act of 1996, which required comparable lifetime and annual dollar limits for mental health (but not substance use disorder) services and for medical or surgical coverage;4 and the Federal Employees Health Benefits (FEHB) program parity directive, which required federal employees’ health plans to offer comprehensive benefits for mental health and substance use disorders.

The directive had an effect on the passage of federal parity legislation by showing that when coupled with managed care techniques to control spending, parity could increase financial protections for users of mental health and substance use disorder services without increasing total costs. The directive also laid the groundwork for including substance use disorder benefits in federal parity.5

By removing treatment limits for those benefits, federal parity and associated regulations6,7 constituted a potentially important step toward addressing poor rates of treatment for substance use disorders in the United States.2 One area of contention during the debate over passage of federal parity was whether the law should require parity for out-of-network services.4 Before passage of the federal parity law, other parity initiatives applied only to in-network services.4 After extended debate in Congress, the final version of the 2008 federal parity law applied parity to both in-network and out-of-network services. Previous parity initiatives applied solely to in-network services, so to date no research evidence exists on the impact of extending parity to out-of-network benefits.

The Out-Of-Network Benefit Debate

In many health plans, beneficiaries can use either in-network or out-of-network providers. However, beneficiaries are subject to increased cost sharing and balance billing—that is, a larger part of the bill is not covered by the insurer and thus must be paid directly by the patient—if they choose to seek care outside the network.8

State parity laws and the FEHB parity directive applied only to in-network services.4 Under these parity initiatives, many health plans established out-of-network substance use disorder benefits with higher cost sharing and special limits on the number of inpatient days and outpatient visits for out-of-network services. For example, Colleen Barry and coauthors found that under the federal employee parity directive, all fee-for-service health plans established limited out-of-network substance use disorder benefits similar to the restricted in-network benefits offered before parity.9 As a result, enrollees benefited from parity only if they used in-network benefits. Federal parity does not require plans to offer out-of-network substance use disorder services, but if they do offer these services, they must offer them at parity.

By participating in networks, physicians gain increased access to a high volume of patients. In addition, networks allow insurers to negotiate lower reimbursement rates with providers, which can lead to lower enrollee premiums. Insurers can also use networks to manage quality and efficiency of care by excluding poor-quality or inefficient providers. A potential downside of physician networks is that they may not include adequate numbers of specialty providers to meet enrollees’ health care needs.8

Insurers have direct oversight of in-network providers and the ability to control in-network utilization with managed care techniques; they have less control over out-of-network providers. As a result, insurers have historically been concerned that requiring parity for out-of-network benefits could lead to increases in utilization and costs.10

However, in the federal parity debate, behavioral health experts, parity advocates, and some members of Congress expressed concern that applying parity solely to in-network benefits would cause health plans to establish “phantom networks”—that is, networks in which the participating providers lack the capacity to meet the demand for services.4 In addition, there was concern that if out-of-network benefits were excluded from federal parity requirements, health plans could employ restrictive limits on visits and high cost sharing for out-of-network mental health or substance use disorder services to discourage people who might want to use such services from selecting their plan.4

Previous Research On Substance Use Disorder Parity

Previous research has examined the effects of parity on the use of and spending on substance use disorder services. Vanessa Azzone and coauthors found that the FEHB parity directive led to decreases in out-of-pocket spending on the services but had minimal impact on total spending, utilization, or quality of care.11 In an evaluation of Oregon’s parity law, John McConnell and colleagues found that parity was associated with increased use of substance use disorder services and total spending, but no changes in out-of-pocket spending.12

In a study of all state substance use disorder parity laws, Hefei Wen and coauthors found that these laws increased treatment rates for the disorders by 9 percent.13 Susan Busch and colleagues examined outcomes of substance use disorder services after the first year of federal parity implementation and concluded that federal parity was associated with small increases in the use of and total spending on the services, but with no change in out-of-pocket spending on them and no changes in identification of the disorders or initiation of and engagement in their treatment.14

In a 2007 study Darrel Regier and coauthors examined out-of-network mental health or substance use disorder benefits in the FEHB program.15 The authors found that two-thirds of specialty mental health providers in the Washington, D.C., area did not participate in federal employee health plan networks, which suggests that extending parity to out-of-network mental health or substance use disorder services could improve enrollees’ ability to access needed care.

The Present Study

The goal of the present study was to examine the effect of federal parity on the use of and spending on out-of-network substance use disorder services. We assessed the effects of federal parity on the probability of such out-of-network use, the number of out-of-network services per user, and both total and out-of-pocket spending on out-of-network services.

Previous work has shown different effects of parity on mental health compared to substance use disorders. Therefore, we considered the effects of federal parity on mental health services in a separate paper.16

Study Data And Methods

STUDY DESIGN

We used an interrupted time-series design to assess changes attributable to federal parity in trends in the use of and spending on out-of-network substance use disorder services. We compared those trends in the thirty-six months prior to federal parity implementation (January 2007–December 2009) to the same trends in the thirty-six months after federal parity went into effect (January 2010–December 2012).We also compared the observed trends in the postparity period to the trends that would have been expected if federal parity had not been implemented.

To conduct the study, we analyzed insurance claims for people covered by large self-insured employers. These employers are exempt from state insurance benefit mandates under the Employment Retirement Income Security Act of 1974.17 Thus, we were able to assess the effect of federal parity on the use of and spending on out-of-network substance use disorder services in a study population not subject to previously enacted state-level substance use disorder parity laws. This study was deemed exempt from review by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

DATA SOURCE

We analyzed data for 2007–12 from the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database. This is a longitudinal database that includes insurance claims for all billable inpatient, outpatient, and pharmacy services used by employees and dependents covered by large self-insured employers across the United States. Because prescription drugs are unrelated to physician networks and by definition cannot be provided out of network, we excluded pharmacy claims from our analytic data set.

STUDY POPULATION

To identify people who used substance use disorder services, we used well-established algorithms with specific diagnoses, diagnosis-related group (DRG) codes, and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes for the services.5,14,18 An inpatient substance use disorder service was defined as an inpatient claim with a primary diagnosis of substance use disorder (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM], diagnostic code 291, 292, 303, 304, 305.0, 305.2–7, or 305.9) or a substance use disorder DRG code (894–7). An outpatient substance use disorder service was defined as an outpatient claim with a primary diagnosis of substance use disorder or a substance use disorder–specific procedure code.

People were included in the study sample for a given calendar year if they used any substance use disorder services and had continuous insurance plan enrollment for that entire year. The final analytic sample consisted of 525,620 people who used substance use disorder services at least once during the study period.

MEASURES

All measures were calculated at the month level. To measure federal parity, we created a binary variable that was coded as 0 for the thirty-six months before parity (2007–09) and 1 for the thirty-six months after parity (2010–12). To measure time, we created a continuous variable that indicated the time in months from federal parity implementation (the values ranged from –35 to 36).

The MarketScan commercial claims database included a variable that indicated whether a given service was provided in network or out of network. We used the variable to create the following four outcome measures of interest: the probability in a given month of any out-of-network substance use disorder service use among people who used substance use disorder services; and per user of out-of-network substance use disorder services per month, the average number of those services used, and both the average total spending and the average out-of-pocket spending on those services per user per month.

Total spending for substance use disorders included both insurers’ spending and enrollees’ out-of-pocket spending. Out-of-pocket spending included deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance but not balance billing. Thus, our out-of-pocket spending estimates should be interpreted as minimums.

Spending measures were adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index and are reported in 2012 dollars. All outcome measures were calculated separately for inpatient and outpatient services, with one exception: Because inpatient stays can include both in-network and out-of-network services, we did not measure the number of out-of-network inpatient stays per user.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We used an interrupted time-series modeling strategy to examine the effect of federal parity on outcomes. The month was the unit of analysis, and all outcomes were modeled as continuous variables. Specifically, for each outcome, a model was fitted that predicted monthly averages of that outcome as a function of the binary federal parity indicator, the continuous month variable, and an interaction between federal parity and month. To control for monthly trends in use and spending, the models included twelve binary month indicator variables (that is, one variable for each month). The federal parity variable indicated whether there was an immediate change in each outcome at the point of federal parity implementation. The interaction term indicated whether there was a change in slope in the outcome in the period after federal parity that was attributable to the law, relative to the slope in the period before federal parity. To account for correlation in outcomes between consecutive months, we used Yule-Walker regression models with first-order autocorrelation parameters.19

The main models included all substance use disorder services. However, previous research on the effects of the state parity law implemented in Oregon suggested that parity has differential effects on alcohol versus drug treatment.12 Thus, we also ran separate models for alcohol and drug use disorder services.

To generate expected use and spending in the absence of federal parity, we used pre-parity trends in outcomes to calculate expected values for 2010–12. These forecasted values represent a continuation of the trends in use and spending observed in 2007–09.

To assess the robustness of our results, we examined the effects of federal parity on out-of-network service use for diabetes, a general medical condition. Users of diabetes services are not a precise comparison group for people who use substance use disorder services. However, this analysis did provide some information about changes in the market for general out-of-network services.

To examine the validity of comparing out-of-network use of diabetes services to out-of-network use of substance use disorder services, we conducted a test of parallel trends in the period before federal parity. We found no significant differences in the use of or spending on the two types of services (for the results of this test, see online Appendix Exhibit A).20 Although this result is not conclusive, it bolsters our confidence that in the absence of federal parity, there would have been similar changes in the use of and spending on care for diabetes and substance use disorders. However, secular trends may have uniquely influenced use and spending for either condition in the period after federal parity.

We also tested whether there were any changes in the use of and spending on out-of-network substance use disorder services after federal parity regulations were implemented in January 2011, the date when most health plans were expected to begin complying with the interim final rules released in February 2010.7 These rules clarified that the processes, evidentiary standards, and other factors used to determine nonquantitative treatment limitations such as medical management and preauthorization can be no more stringent for mental health or substance use disorder services than for medical or surgical services.

LIMITATIONS

This study had several limitations. Importantly, it did not use a comparison group. A drawback to the interrupted time-series modeling approach is that secular changes in out-of-network substance use disorder treatment unrelated to federal parity could have driven our results.

Identifying an appropriate comparison group is challenging in the context of a national policy change implemented at a single point in time. As noted above, to address this limitation and examine the role of secular trends, we used identical methods to examine the effects of federal parity on out-of-network use of diabetes services. If our findings on out-of-network use of substance use disorder services were driven by secular trends, we would have expected to see the same trends in out-of-network use of diabetes services. The fact that we did not increased our confidence that we were identifying the effects of federal parity.

Our analysis used administrative claims data, which do not include patient interviews or medical chart reviews to confirm diagnoses or services received. Our study was designed to assess the net effect of federal parity implementation on the use of and spending on out-of-network substance use disorder services. However, we were unable to disentangle the specific mechanisms by which federal parity influenced these outcomes. In addition to changing substance use disorder benefit design, federal parity might have led to changes in supply-side constraints imposed by insurers (for example, requiring prior authorization or restricting referrals) and might have reduced the stigma of being treated for a substance use disorder. Both of these possible changes could have influenced out-of-network treatment for the disorders.

Furthermore, federal parity went into effect several months before the ACA became law, and the entire post-parity period of our analysis occurred well before most major provisions of the ACA went into effect, in January 2014. But some provisions of the ACA were implemented in 2010–13. The changing landscape of health care financing and delivery in the United States during this period could have influenced our results.

Finally, our study used a large convenience sample of privately insured people. Nonetheless, the MarketScan commercial claims database is not nationally representative, and our results may not apply to other insured populations. As noted above, our use of claims data did not allow us to capture out-of-pocket spending related to balance billing, and our study did not capture substance use disorder services paid for entirely out of pocket. These unobserved costs could have led to significant financial burden that we were unable to measure.

Study Results

Demographic characteristics of the twelvemonth continuously enrolled sample remained stable during the study period (Exhibit 1). The unadjusted probability of any out-of-network service use was higher among inpatient service users (18–23 percent per year) than among out-patient service users (12–17 percent per year). That probability increased slightly during the study period on both the inpatient and out-patient side. The average number of out-of-network outpatient visits per user increased from seven to seventeen. Average total spending on out-of-network inpatient and outpatient services more than doubled during the study period.

Exhibit 1.

Characteristics Of Substance Use Disorder (SUD) Service Users, 2007–2012

| Pre-parity

|

Post-parity

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |

| all service users | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Number | 61,188 | 86,312 | 101,474 | 115,350 | 144,092 | 171,547 |

| Female | 50.8% | 51.3% | 52.3% | 52.5% | 51.9% | 52.4% |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 18–34 | 37.9 | 37.9 | 37.2 | 36.1 | 39.6 | 39.4 |

| 35–44 | 25.9 | 25.5 | 24.9 | 24.2 | 22.2 | 21.7 |

| 45–54 | 27.0 | 26.8 | 27.1 | 27.6 | 25.9 | 25.7 |

| 55–64 | 9.2 | 9.8 | 10.8 | 12.1 | 12.3 | 13.2 |

| Census region | ||||||

| Northeast | 11.8 | 13.3 | 13.4 | 13.0 | 12.7 | 12.5 |

| Midwest | 26.5 | 24.5 | 21.6 | 20.6 | 20.4 | 20.0 |

| South | 38.9 | 39.7 | 42.5 | 43.4 | 45.6 | 46.1 |

| West | 22.8 | 22.5 | 22.4 | 23.1 | 21.3 | 21.4 |

| Urban | 85.6 | 86.5 | 86.0 | 86.2 | 86.2 | 86.2 |

|

| ||||||

| inpatient service users | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Number | 6,644 | 8,468 | 8,666 | 8,753 | 10,791 | 12,196 |

| Used any out-of-network inpatient SUD service | 19.7% | 19.5% | 18.3% | 18.5% | 20.4% | 22.5% |

| Average total out-of-network SUD spending | $5,175.8 | $5,841.7 | $6,120.2 | $7,576.6 | $10,167.9 | $11,360.6 |

| Average out-of-pocket out-of-network SUD spending | 1,271.1 | 1,643.2 | 1,546.6 | 1,582.1 | 1,856.8 | 2,008.6 |

|

| ||||||

| outpatient service users | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Number | 59,424 | 84,141 | 99,382 | 113,419 | 141,868 | 169,267 |

| Used any out-of-network outpatient SUD service | 13.1% | 12.3% | 13.2% | 13.5% | 14.9% | 16.9% |

| Average number of out-of-network SUD visits | 6.6 | 6.7 | 6.9 | 8.6 | 11.6 | 16.8 |

| Average total out-of-network SUD spending | $1,208.7 | $1,380.6 | $1,472.0 | $1,881.1 | $2,907.3 | $3,601.1 |

| Average out-of-pocket out-of-network SUD spending | 403.8 | 433.5 | 450.7 | 522.3 | 620.7 | 702.2 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2007–12 from the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database. NOTES “Parity” refers to the 2010 implementation of the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008. Percentages of characteristics were calculated for the 525,620 people who had twelve-month continuous enrollment in a given year and used any inpatient or outpatient SUD service in that year. Inpatient SUD service outcomes were calculated for the subset of people in the study population who used inpatient SUD services in a given year (during the study period, 49,071 people used these services). Outpatient SUD service outcomes were calculated for the subset of people in the study population who used outpatient SUD services in a given year (during the study period, 516,983 people used these services). Some people used both inpatient and outpatient SUD services. Spending was inflation adjusted using the Consumer Price Index and is reported in 2012 dollars.

Federal parity was associated with increases in the probability of any use of out-of-network in-patient substance use disorder services among users of the services at a rate of 0.0024 people using services per month. In 2010, the first year of federal parity implementation, this translated into an 8.7 percent increase in out-of-network service use over what would have been expected in the absence of federal parity (data not shown). Similarly, federal parity increased the rate of average total spending on out-of-network inpatient substance use disorder services by $49.81 per user per month (Exhibit 1).

Federal parity increased the probability of any use of out-of-network outpatient substance use disorder services among users of those services at a rate of 0.0016 per month (Exhibit 2). This translates into a 4.3 percent increase over what would have been expected in the absence of federal parity during the first year of the law’s implementation (data not shown).

Exhibit 2.

Use Of And Spending On Out-Of-Network Substance Use Disorder (SUD) Services Attributable To Federal Parity, 2007–12

| Coefficient | Standard error | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| inpatient service users (per month) | |||

|

| |||

| Probability of any out-of-network inpatient SUD service use | |||

| Parity | −0.0083 | 0.0077 | 0.284 |

| Time | −0.0006 | 0.0003 | 0.027 |

| Interactiona | 0.0024 | 0.0004 | <0.001 |

| Average total out-of-network inpatient SUD spending | |||

| Parity | $207.90 | $379.54 | 0.586 |

| Time | 38.69 | 12.78 | 0.004 |

| Interactiona | 49.81 | 17.61 | 0.007 |

| Average out-of-pocket out-of-network inpatient SUD spending | |||

| Parity | −$121.06 | $83.53 | 0.153 |

| Time | 7.57 | 2.82 | 0.009 |

| Interactiona | 2.55 | 3.90 | 0.515 |

|

| |||

| outpatient service users, per month | |||

|

| |||

| Probability of any out-of-network outpatient SUD service use | |||

| Parity | −0.0068 | 0.0048 | 0.165 |

| Time | −0.0004 | 0.0002 | 0.030 |

| Interactiona | 0.0016 | 0.0003 | <0.001 |

| Average number of out-of-network outpatient SUD services | |||

| Parity | −0.0210 | 0.2445 | 0.932 |

| Time | 0.0035 | 0.0104 | 0.735 |

| Interactiona | 0.1538 | 0.0162 | <0.001 |

| Average total out-of-network outpatient SUD spending | |||

| Parity | $10.91 | $53.74 | 0.840 |

| Time | 6.25 | 2.09 | 0.004 |

| Interactiona | 24.80 | 3.16 | <0.001 |

| Average out-of-pocket out-of-network outpatient SUD spending | |||

| Parity | −$4.51 | $12.60 | 0.723 |

| Time | 1.78 | 0.45 | <0.001 |

| Interactiona | 0.88 | 0.64 | 0.173 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2007–12 from the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database. NOTES “Parity” refers to the 2010 implementation of the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008. Results were estimated using Yule-Walker regression models with first-order autocorrelation parameters (see Note 19 in text). Model covariates included twelve-month indicator variables to adjust for month-specific trends in outcomes. Inpatient SUD service outcomes were calculated for the subset of people in the study population who used those inpatient SUD services in a given month (during the study period, 49,071 people used these services). Outpatient SUD service outcomes were calculated for the subset of people in the study population who used outpatient SUD services in a given month (during the study period, 516,983 people used these services). Spending was inflation adjusted using the Consumer Price Index and is reported in 2012 dollars.

Interaction is between parity and time.

In addition, federal parity increased the average number of out-of-network outpatient substance use disorder visits per user of the services at a rate of 0.15 per month. This translates into an average increase of twelve additional visits (that is, one additional visit per month) in 2010 for people who used the services every month. Federal parity increased the rate of average total out-of-network spending on these outpatient services by $24.80 per user per month but had no significant effect on out-of-pocket spending.

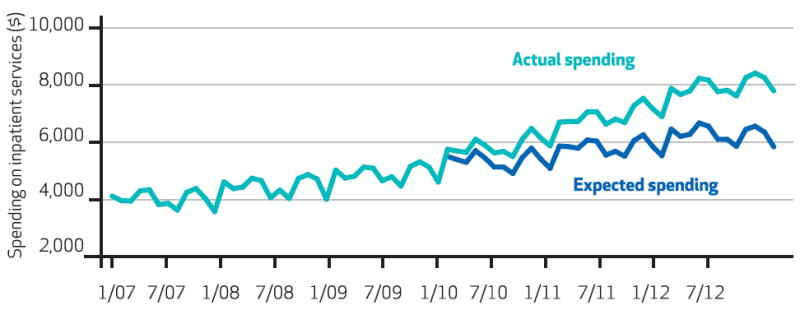

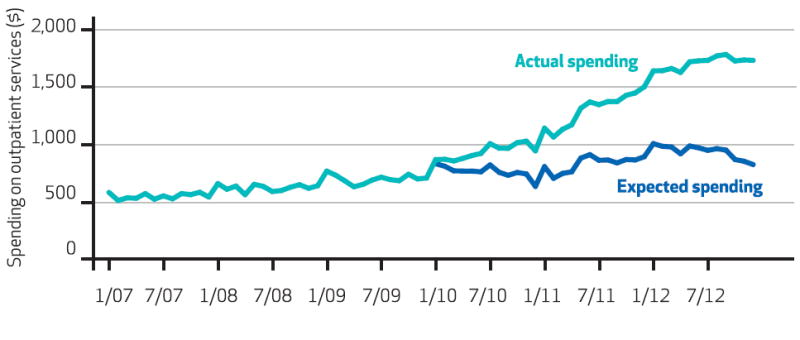

Exhibits 3 and 4 display the trends in actual out-of-network spending and in forecasted spending in the absence of federal parity on inpatient and outpatient use, respectively, of substance use disorder services. Graphical depictions of regression results for other inpatient use and spending outcomes and for outpatient outcomes are included in Appendix Exhibits B and C, respectively.20

Exhibit 3. Difference In Total Out-Of-Network Inpatient Spending On Substance Use Disorder Services Per User Of The Services, With And Without Federal Parity, 2007–12.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2007–12 from the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database. NOTES During the study period, 49,071 people in the sample used inpatient substance use disorder services. “Expected spending” is a continuation of the trends in use and spending observed in 2007–09, which represents spending that would have happened in the absence of federal parity.

Exhibit 4. Difference In Total Out-Of-Network Outpatient Spending On Substance Use Disorder Services Per User Of The Services, With And Without Federal Parity, 2007–12.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2007–12 from the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database. NOTES During the study period, 516,983 people in the sample used outpatient substance use disorder services. “Expected spending” is a continuation of the trends in use and spending observed in 2007–09, which represents spending that would have happened in the absence of federal parity.

When we looked separately at the effects of federal parity on drug and alcohol disorder services, we found that the policy increased the probability of using inpatient and outpatient drug and alcohol services (p < 0001; data not shown). Federal parity was associated with increases in total spending for out-of-network in-patient drug use disorder services and for out-of-network outpatient drug and alcohol services (p < 001). The overall model results showed no effect of the policy on out-of-pocket spending on out-of-network outpatient substance use disorder services. However, federal parity was associated with small but significant increases in this outcome for both alcohol and drugs in the stratified analysis (Appendix Exhibit D).20

Federal parity was not associated with changes in the probability of use of, or total spending on, out-of-network outpatient diabetes services (Appendix Exhibit A).20 We found no significant changes in out-of-network substance use disorder service use and spending outcomes after the 2011 implementation of the interim final rules7 that clarified the nonquantitative treatment limitations (Appendix Exhibit E).20

Discussion

This study is the first to examine the effects of extending parity to out-of-network substance use disorder care under the federal parity law. We looked at the effects of federal parity on out-of-network services for substance use disorders, given substantial concerns about under-treatment.2,21 Our findings indicated that federal parity led to an increased probability of the use of out-of-network substance use disorder services, an increased number of out-of-network out-patient visits for the disorders, and increased total spending on out-of-network substance use disorder services among users of services for the disorders but had no effect on out-of-pocket spending.

Our results suggest that inclusion of the out-of-network benefit in the federal parity law achieved its intended goal of improving access to substance use disorder services outside of health plans’ physician networks and had minimal overall impact on total spending. In 2010 the average expenditure per private health insurance enrollee in the United States was $4,506.22 Federal parity was associated with increases in total spending per user of out-of-network substance use disorder services. However, relatively few people use such services, and the rate of spending increase—$24.80 a month among the subset of people who used the out-of-network outpatient services—was minimal relative to total per enrollee expenditures.

Furthermore, substance use disorder services account for a small proportion of total health care use and spending in the United States. In 2009, the year before federal parity went into effect, the proportion was 1 percent, according to Tami Mark and coauthors, and it did not change between 2009 and 2014.23

One of the core goals of federal parity was to reduce the financial burden on consumers of substance use disorder services. However, we found no effect of federal parity on trends in out-of-pocket spending for use of out-of-network substance use disorder services. On the surface, this finding is surprising.

Previous research has shown that the FEHB program parity directive led to decreased out-of-pocket spending.5,11 And data have shown that higher cost sharing for substance use disorder services, compared to that for other medical services, was common prior to the implementation of federal parity.1 If the law had the effect of decreasing cost sharing for the use of out-of-network substance use disorder services and if consumers’ level of service use remained constant before and after federal parity—as occurred following the FEHB program parity directive—out-of-pocket spending should decrease.

However, our study showed that federal parity implementation was associated with an increase in the average number of out-of-network substance use disorder outpatient visits per user. This suggests that the lack of effect of federal parity on out-of-pocket spending was due to an increased number of visits per user, not to the failure of the law to reduce cost sharing.

Consistent with previous studies showing that out-of-network service use is more prevalent in mental health care than in general medical care,24,25 we found high rates of out-of-network use of substance use disorder services among our study population of privately insured people. In 2012, 23 percent of the users of inpatient substance use disorder services in our study used at least one out-of-network inpatient service, and 17 percent of users of outpatient services for the disorders used out-of-network outpatient care at least once (Exhibit 1). In contrast, a 2011 national survey of people who used health care services in a given year found that 7 percent went out of network for general health care.24

Our study demonstrates high rates of out-of-network use of substance use disorder services among privately insured people and shows increases in the out-of-network use of such services attributable to federal parity. However, our methodology did not allow us to assess consumers’ reasons for seeking out-of-network care.

Importantly, our study was unable to assess the adequacy of substance use disorder provider networks. Previous research has examined factors that contribute to high use of out-of-network services in mental health, but to our knowledge no comparable studies exist for substance use disorders. Studies have shown that psychiatrists are less likely than other providers to accept private insurance26 and participate in physician networks,27 which could lead consumers to seek out-of-network care. In a national survey conducted in 2011, Kelly Kyanko and coauthors found that most privately insured adults who sought out-of-network mental health care did so to obtain care from a recommended or high-quality provider or to continue a previously established relationship with a provider.24

Behavioral health advocates and policy makers are concerned that consumers may be forced out of network because availability of in-network behavioral health providers is lacking. However, fewer than 3 percent of the respondents in Kyanko and coauthors’ survey reported that the primary reason they went out of network for mental health care was because there was no in-network physician available in their area or because they were unable to schedule a timely appointment with an in-network physician.24 Some of these drivers of out-of-network mental health care may also apply to care for substance use disorders.

Conclusion

Our study identified increases in the use of and total spending on out-of-network substance use disorder services attributable to federal parity. Understanding the effects of the law on these out-of-network services is critical, given that the ACA required Marketplace plans to include these services as an essential health benefit and expanded federal parity to the individual and small-group insurance markets. Our results suggest that these expansions will improve access to out-of-network substance use disorder services with minimal overall impact on total spending. Future research should assess providers’ participation in networks and consumers’ reasons for seeking out-of-network care for the disorders.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from the NIDA (Grant No. R01DA026414 to Emma McGinty, Susan Busch, and Colleen Barry) and the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant No. R01MH093414 to all of the, authors).

Footnotes

Results from this study were presented at the annual National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) Addiction Health Services Research Conference in Boston, Massachusetts, October 16, 2014

Contributor Information

Emma E. McGinty, Email: bmcginty@jhu.edu, assistant professor of health policy and management and of mental health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, in Baltimore, Maryland.

Susan H. Busch, professor of health policy at Yale School of Public Health, in New Haven, Connecticut

Elizabeth A. Stuart, professor of mental health, biostatistics, and health policy and management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Haiden A. Huskamp, professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, in Boston, Massachusetts

Teresa B. Gibson, faculty research associate of health care policy at Harvard Medical School and a senior research scientist at the Arbor Research Collaborative for Health, in Ann Arbor, Michigan

Howard H. Goldman, professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, in Baltimore

Colleen L. Barry, associate professor of health policy and management and of mental health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

NOTES

- 1.Gabel JR, Whitmore H, Pickreign JD, Levit KR, Coffey RM, Vandivort-Warren R. Substance abuse benefits: still limited after all these years. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(4):w474–82. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.4.w474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Rockville (MD): SAMHSA; [2015 Jun 4]. Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: volume I. Summary of national findings [Internet] Available from: http://archive.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2k9NSDUH/2k9Results.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barry CL, Sindelar JL. Equity in private insurance coverage for substance abuse: a perspective on parity. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(6):w706–16. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.6.w706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barry CL, Huskamp HA, Goldman HH. A political history of federal mental health and addiction insurance parity. Milbank Q. 2010;88(3):404–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00605.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldman HH, Frank RG, Burnam MA, Huskamp HA, Ridgely MS, Normand SL, et al. Behavioral health insurance parity for federal employees. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(13):1378–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Internal Revenue Service, Department of the Treasury; Employee Benefits Security Administration, Department of Labor; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Department of Health and Human Services. Final rules under the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008; technical amendment to external review for multi-state plan program. Final rules. Fed Regist. 2013;78(219):68239–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Internal Revenue Service, Department of the Treasury; Employee Benefits Security Administration, Department of Labor; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Department of Health and Human Services. Interim final rules under the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008. Interim final rules with request for comments. Fed Regist. 2010;75(21):5409–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kyanko KA, Busch SH. The out-of-network benefit: problems and policy solutions. Inquiry. 2012;49(4):352–61. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_49.04.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barry CL, Ridgely MS. Mental health and substance abuse insurance parity for federal employees: how did health plans respond? J Policy Anal Manage. 2008;27(1):155–70. doi: 10.1002/pam.20311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barry CL, Frank RG, McGuire TG. The costs of mental health parity: still an impediment? Health Aff (Millwood) 2006;25(3):623–34. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.3.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azzone V, Frank RG, Normand SL, Burnam AM. Effect of insurance parity on substance abuse treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(2):129–34. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.2.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McConnell KJ, Ridgely MS, McCarty D. What Oregon’s parity law can tell us about the federal Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act and spending on substance abuse treatment services. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;124(3):340–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wen H, Cummings JR, Hockenberry JM, Gaydos LM, Druss BG. State parity laws and access to treatment for substance use disorder in the United States: implications for federal parity legislation. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(12):1355–62. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Busch SH, Epstein AJ, Harhay MO, Fiellin DA, Un H, Leader D, Jr, et al. The effects of federal parity on substance use disorder treatment. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(1):76–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Regier DA, Bufka LF, Whitaker T, Duffy FF, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al. Parity and the use of out-of-network mental health benefits in the FEHB program. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(1):w70–83. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.1.w70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Busch SH, McGinty EE, Stuart EA, Huskamp HA, Gibson TB, Goldman HH, et al. Was federal parity implementation associated with changes in out-of-network mental health care use and spending? Unpublished paper. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2261-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butler PA. Washington (DC): Alpha Center; 2000. Jan, [2015 May 11]. ERISA preemption manual for state health policy makers [Internet] Available from: http://www.statecoverage.org/files/ERISA%20Preemption%20Manual%20for%20State%20Health%20 Policymakers.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Busch AB, Yoon F, Barry CL, Azzone V, Normand SL, Goldman HH, et al. The effects of mental health parity on spending and utilization for bipolar, major depression, and adjustment disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(2):180–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hyndman RJ. Yule-Walker estimates for continuous-time autoregressive models. J Time Ser Anal. 1993;14(3):281–96. [Google Scholar]

- 20.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online

- 21.Capoccia VA, Grazier KL, Toal C, Ford JH, 2nd, Gustafson DH. Massachusetts’s experience suggests coverage alone is insufficient to increase addiction disorders treatment. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(5):1000–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.CMS.gov. National health expenditure data [Internet] Baltimore (MD): Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; [2015 May 12]. last modified 2014 Dec 9. Available from: http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpend-Data/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.html. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mark TL, Levit KR, Yee T, Chow CM. Spending on mental and substance use disorders projected to grow more slowly than all health spending through 2020. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(8):1407–15. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kyanko KA, Curry LA, Busch SH. Out-of-network provider use more likely in mental health than general health care among privately insured. Med Care. 2013;51(8):699–705. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31829a4f73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stein BD, Meili R, Tanielian TL, Klein DJ. Outpatient mental health utilization among commercially insured individuals: in- and out-of-network care. Med Care. 2007;45(2):183–6. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000244508.55923.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, Pincus HA. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):176–81. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Malley AS, Reschovsky JD. No exodus: physicians and managed care networks [Internet] Washington (DC): Center for Studying Health System Change; 2006. May, [2015 May 12]. (Tracking Report No. 14). Available from: http://www.hschange.com/CONTENT/838/ [Google Scholar]