Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To determine the association of multiple chronic conditions with risk of incident mild cognitive impairment (MCI)/dementia.

DESIGN

Prospective cohort study

SETTING

Olmsted County, Minnesota.

PARTICIPANTS

Cognitively normal individuals (N=2,176) enrolled in the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging (MCSA).

MEASUREMENTS

Participants were randomly selected from the community and evaluated by a study coordinator, a physician, and underwent neuropsychometric testing at baseline and at 15-month intervals to assess diagnoses of MCI and dementia. We electronically captured information on International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision (ICD-9) codes for chronic conditions in the five years prior to enrollment using the Rochester Epidemiology Project medical records linkage system. We defined multimorbidity as having two or more chronic conditions and examined the association of multimorbidity with MCI/dementia using Cox proportional hazards models.

RESULTS

Among 2,176 cognitively normal participants (mean [±SD] age 78.5 [±5.2] years; 50.6% men), 1,884 (86.6%) had multimorbidity. The risk of MCI/dementia was elevated in persons with multimorbidity (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.38; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.05–1.82). The HR was stronger in persons with ≥4 conditions (HR: 1.61; 95%CI, 1.21–2.13) compared to persons with only 0 or 1 conditions, and for men (HR: 1.53, 95% CI, 1.01– 2.31) than for women (HR: 1.20, 95% CI, 0.83– 1.74).

CONCLUSION

In older adults, having multiple chronic conditions is associated with an increased risk of MCI/dementia. This is consistent with the hypothesis that multiple etiologies may contribute to MCI and late-life dementia. Preventing chronic diseases may be beneficial in delaying or preventing MCI or dementia.

Keywords: mild cognitive impairment, dementia, multimorbidity

INTRODUCTION

Multimorbidity, defined as the coexistence of 2 or more chronic conditions in an individual,1 is highly prevalent among older adults.2 Estimates of prevalence increase with age, and range from 55% to 98% in populations older than 60 years of age.1 Advances in the management of chronic conditions have resulted in slower disease progression and/or delayed mortality, resulting in an increase in the prevalence of multimorbidity.3 The risk of disability, functional decline, premature death, poor quality of life, polypharmacy, increased medical consultation, hospitalizations and length of stay, increased use of emergency care, and higher health care costs are all increased in individuals with multimorbidity.1, 4 The presence of certain chronic conditions may also enhance the development of additional chronic conditions.3

With the growing number of elderly persons ages 65 years and older in the US and worldwide, the implications of multimorbidity for risk of age-related conditions such as mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia is highly relevant for development of strategies to reduce risk. In particular, multimorbidity may contribute to increased risk of MCI, an important precursor for AD and other dementias.5–8 However, the association has not been comprehensively investigated in a population-based setting. The primary objective of this study was to determine the association between multimorbidity and incident MCI/dementia in a cohort of cognitively normal individuals enrolled in the prospective, population-based Mayo Clinic Study of Aging (MCSA).

METHODS

Study Cohort at Baseline

Details of the study design and methodology of the MCSA have previously been published.9, 10 Briefly, residents of Olmsted County, MN aged 70–89 years on the prevalence (index) date (October 1, 2004) were enumerated using the medical records linkage system of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP).11 An age and sex-stratified random sample of eligible subjects (without dementia, not terminally ill or in hospice) was invited to participate in-person or by telephone. To maintain the study sample size recruitment is ongoing. This study includes additional participants recruited from an enumeration of the County population on March 1, 2008, and on November 1, 2009, 2010 and 2011. The current study is restricted to participants who were evaluated in-person (between 2004 and 2011), were cognitively normal at the baseline evaluation, and had at least one follow-up evaluation (N=2,176).

Identification of MCI/Dementia

Participants were evaluated by a nurse or study coordinator and a physician, and underwent neuropsychometric testing administered by a trained psychometrist. The interview by the coordinator included ascertainment of demographic information, questions about memory were administered to the participant, and the Clinical Dementia Rating scale12 and the Functional Activities Questionnaire were administered to an informant.13 Demographic information was also ascertained by interview. The physician evaluation included administration of the Short Test of Mental Status,14 a medical history review, and a complete neurological examination. Neuropsychological testing was performed using nine tests to assess performance in four cognitive domains: memory, executive function, language, and visuospatial skills.9, 10,15 Apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype was assessed from a blood draw performed at baseline.

The study coordinator and physician who saw the participant and a neuropsychologist who reviewed the psychometric testing data reviewed all information collected for a participant, and a diagnosis of MCI, dementia or normal cognition was made by consensus. The diagnosis of MCI was based on previously published criteria9, 10, 16 A diagnosis of dementia was based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition criteria.17 Participants were classified as cognitively normal if they performed in the normative range and did not meet criteria for MCI or dementia.9, 10, 16

Longitudinal Follow-Up

Follow-up was performed at 15-month intervals using the same clinical protocol for evaluation and diagnosis as at baseline. To avoid potential bias, clinical and cognitive findings from previous evaluations were not considered in making a diagnosis. Subjects who participated at baseline but declined an in-person evaluation at follow-up were invited to participate in a telephone interview that included the Telephone Interview of Cognitive Status-modified (TICS-m),18 the Clinical Dementia Rating scale,12 and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire.19

Identification of Chronic Conditions

For each MCSA participant, the diagnostic indices of the REP were searched electronically to identify the International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision (ICD-9) codes associated with any health care visit within 5 years prior to enrollment (i.e., 5-year capture frame). The REP captures all persons who have resided in Olmsted County, MN residents at any time from 1966 to the present; only 2% of residents refuse to participate at all the health care providers. Approximately 90% of residents 70 years and older return for a follow-up visit within a year after their baseline visit assuring an excellent ascertainment of diagnosed medical conditions through the years.20 Specific ICD-9 codes for the 19 chronic conditions (excluding dementia) proposed by the US Department of Health and Human Services in 2010 for studying multimorbidity were identified for each individual.21 A person was considered as having a specific chronic condition if they received two ICD-9 codes for the given condition separated by more than 30 days within the 5-year capture frame.22 There were no cases of autism spectrum disorder or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), resulting in a possible maximum of 17 chronic conditions (i.e., hyperlipidemia, hypertension, depression, diabetes, arthritis, cancer, cardiac arrhythmias, asthma, coronary artery disease, substance abuse disorders (drugs and alcohol), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, osteoporosis, chronic kidney disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, schizophrenia, hepatitis).

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consent

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Mayo Clinic and of Olmsted Medical Center. Written informed consent was obtained prior to participation in the study.

Statistical Analysis

Multimorbidity was defined as the presence of two or more of the 17 conditions in the 5-year capture frame. In addition, mutually exclusive categories of comorbidity were created as having 0 or 1, 2, 3, and 4 or more of the 17 chronic conditions within the 5-year capture frame. Categories of 0 and 1 chronic conditions were combined as the reference group due to the low frequency of subjects with 0 comorbidities (n = 89).

The onset of incident MCI was assigned at the midpoint between the last assessment as cognitively normal and the first-ever assessment as MCI or dementia. Subjects who progressed to dementia without an MCI diagnosis (N=27) at an MCSA evaluation were presumed to have passed through an undetected MCI phase and included as incident events. Subjects who refused participation, could not be contacted, or died during follow-up were censored at their last evaluation. Duration of follow-up was computed from the diagnosis of cognitively normal to first onset of MCI or dementia, censoring, or date of last follow-up.

The associations between multimorbidity and first occurrence of incident MCI or dementia were examined using Cox proportional hazards models with age as the time scale, and with adjustment for sex and education. Potential confounding by the APOE ε4 allele was examined and subgroup analyses by sex were performed. To assess interaction between age and multimorbidity, we built a separate Cox proportional hazards model with follow-up time as the time scale. Although we modeled risk of MCI or dementia, for simplicity we will only refer to this outcome as risk of MCI, hereafter. We grouped persons with 2 and 3 chronic conditions together because risk estimates did not differ when compared to persons with 0 or 1 condition. To account for incident conditions during follow-up, we also categorized participants as having multimorbidity taking into consideration incident comorbid conditions during follow-up. Finally, among persons with multimorbidity, we identified the five most common dyads (any combinations of 2 of the 17 chronic conditions). All analyses were considered significant at a p value ≤ 0.05, and were performed using the SAS statistical software version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Among 2,176 cognitively normal participants (mean age 78.5 years; 50.6% men), 1884 (86.6%) had multimorbidity (≥ 2 chronic conditions; Table 1). However, there were no differences in frequency of multimorbidity, severe multimorbidity (defined here as ≥4 conditions), APOE ε4 allele or duration of follow-up by sex. Table 2 describes the baseline characteristics of participants by number of chronic conditions. Mean age, frequency of obesity and former smoking increased with increasing comorbidity. APOE ε4 genotype was not related to the number of chronic conditions.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants at Baseline

| Characteristic | All N = 2,176 |

Men N = 1101 |

Women N = 1075 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (±SD) | 78.5 (5.2) | 78.2 (4.9) | 78.9 (5.4) |

| Education (years), mean (±SD) | 14.1 (2.9) | 14.4 (3.2) | 13.7 (2.4) |

| Duration of follow-up, mean (±SD) | 4.3 (2.4) | 4.2 (2.4) | 4.4 (2.4) |

| Married, n (%) | 1431 (65.8) | 936 (85.0) | 495 (46.0) |

| APOE ε24/ε34/ε44,a n (%) | 557 (25.7) | 283 (25.8) | 274 (25.7) |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never, n (%) | 1115 (51.2) | 429 (39.0) | 686 (63.8) |

| Former, n (%) | 979 (45.0) | 633 (57.5) | 346 (32.2) |

| Current, n (%) | 82 (3.8) | 39 (3.5) | 43 (4.0) |

| Frequency of chronic conditions | |||

| 0–1 conditions, n (%) | 292 (13.4) | 147 (13.4) | 145 (13.5) |

| 2–3 conditions, n (%) | 700 (32.2) | 348 (31.6) | 352 (32.7) |

| ≥ 4 conditions, n (%) | 1184 (54.4) | 606 (55.0) | 578 (53.8) |

| ≥ 2 conditions (multimorbidity), n (%) | 1884 (86.6) | 954 (86.6) | 930 (86.5) |

Abbreviations: APOE, apolipoprotein E

Information was missing for 11 participants (4 men, 7 women).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Participants at Baseline by Number of Chronic Conditions

| Number of Chronic Conditions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | 0–1 (N=292) |

2 (N=306) |

3 (N=394) |

≥4 (N=1184) |

Total (N=2176) |

p value |

| Age, mean (±SD) | 77.3 (4.9) | 77.4 (4.8) | 78.0 (5.0) | 79.3 (5.2) | 78.5 (5.2) | <.001 |

| Sex, Male, n (%) | 147 (50.3) | 154 (50.3) | 194 (49.2) | 606 (51.2) | 1101 (50.6) | 0.93 |

| Education (years), mean (±SD) | 14.1 (3.0) | 14.5 (2.9) | 14.1 (2.9) | 13.9 (2.9) | 14.1 (2.9) | 0.013 |

| Smoking Status | ||||||

| Never, n (%) | 164 (56.2) | 170 (55.6) | 208 (52.8) | 573 (48.4) | 1115 (51.2) | 0.006 |

| Former, n (%) | 110 (37.7) | 130 (42.5) | 171 (43.4) | 568 (48.0) | 979 (45.0) | |

| Current, n (%) | 18 (6.2) | 6 (2.0) | 15 (3.8) | 43 (3.6) | 82 (3.8) | |

| Body mass Index ≥ 30 (obese),a n (%) | 43 (14.9) | 74 (24.2) | 95 (24.5) | 396 (34.1) | 608 (28.4) | <.001 |

| APOE ε24/ε34/ε44,b n (%) | 69 (23.7) | 69 (22.7) | 107 (27.3) | 312 (26.5) | 557 (25.7) | 0.40 |

Abbreviations: APOE, apolipoprotein E.

Number with missing information: 3 for 0–1 conditions, 7 for 3 conditions, 23 for ≥4 conditions.

Number with missing information: 1 for 0–1 conditions, 2 for 2 conditions, 2 for 3 conditions, 6 for ≥4 conditions.

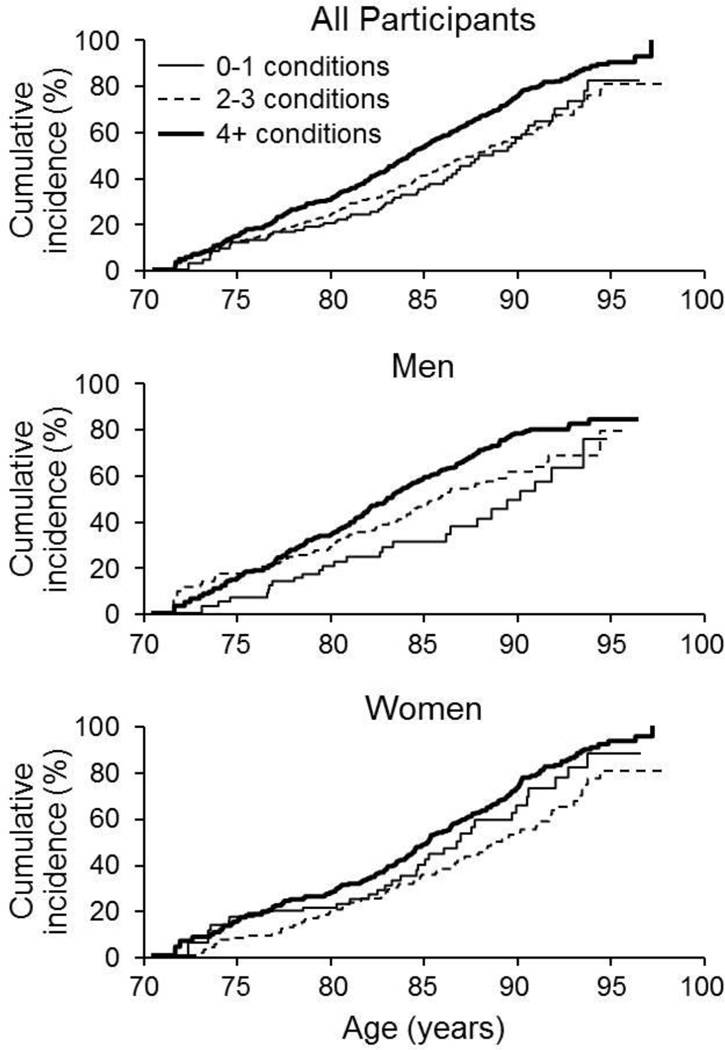

Over a median (IQR) follow-up of 4 (2.4, 6.6) years, 583 participants developed incident MCI or dementia. Multimorbidity was associated with an increased risk of MCI (hazard ratio [HR] 1.38, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.05–1.82) in men and women combined after adjusting for sex and education (Table 3). The association was above 1.0 in men (HR 1.53, 95%CI 1.01–2.31) and women (HR 1.20, 95%CI 0.83–1.74), but was statistically significant in men only. We next examined whether an increasing number of chronic conditions increased the risk of MCI and found that having four or more chronic conditions significantly increased MCI risk in both sexes combined and in men, with a borderline significant increase in risk in women (Figure 1). APOE ε4 genotype was not a confounder of the associations.

Table 3.

Association between Multimorbidity and Incident Mild Cognitive Impairment or Dementia Overall and By Sex

| Total sample | Men | Women | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | N | ||||||||||

| Characteristic | At Risk |

Events | HR (95% CI)a |

P- value |

At Risk |

Events | HR (95% CI)a | P- value |

At Risk |

Events | HR (95% CI)a |

P- value |

| 0–1 condition | 292 | 57 | 1.00 (reference) | 147 | 25 | 1.00 (reference) | 145 | 32 | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| ≥ 2 conditions | 1884 | 526 | 1.38 (1.05, 1.82) | 0.021 | 954 | 257 | 1.53 (1.01, 2.31) | 0.04 | 930 | 269 | 1.20 (0.83, 1.74) | 0.33 |

| 0–1 condition | 292 | 57 | 1.00 (reference) | 147 | 25 | 1.00 (reference) | 145 | 32 | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| 2–3 conditions | 700 | 149 | 1.03 (0.76, 1.39) | 0.86 | 348 | 73 | 1.17 (0.74, 1.85) | 0.50 | 352 | 76 | 0.87 (0.57, 1.32) | 0.51 |

| ≥ 4 conditions | 1184 | 377 | 1.61 (1.21, 2.13) | <0.001 | 606 | 184 | 1.75 (1.15, 2.66) | 0.009 | 578 | 193 | 1.43 (0.98, 2.10) | 0.06 |

| P value for trend | <0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 | |||||||||

Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) retained from Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for sex (where applicable) and years of education, with age as the time scale.

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of mild cognitive impairment or dementia in participants who were cognitively normal at baseline and log rank tests for 2 or 3 and ≥4 chronic conditions compared to 0 or 1 [reference]). All participants: men and women combined, the median age at event was as follows: 0 or 1 conditions, 88.6 years; 2 or 3 conditions, 87.8 years; ≥ 4 conditions, 84.2 years. Log-rank tests (unadjusted for sex and education) were: p=0.009 for comparison of 2 or 3 vs. 0 or 1 conditions and p<0.001 for comparison of ≥4 conditions vs. 0 or 1 conditions. Men: The median age at event was: 0 or 1 condition, 90.1 years; 2 or 3 conditions, 85.9 years; ≥ 4 conditions, 83.0 years. Log-rank tests were: p= 0.046 for comparison of 2 or 3 conditions vs. 0 or 1 conditions and p<0.001 for comparison of ≥4 conditions vs. 0 or 1 conditions. Women: The median age at event was: 0 or 1 conditions, 86.9; 2 or 3 conditions, 89.1; 4+ conditions, 85.2 years. Log-rank tests were: p=0.061 for comparison of 2 or 3 conditions vs. 0 or 1 conditions and p<0.001 for comparison of ≥4 conditions vs. 0 or 1 conditions.

We did not observe a significant interaction of multimorbidity with sex in regard to risk of MCI in any of the analyses, however, the higher estimates of risk in men vs. women suggests potential effect modification by sex. There was also no statistically significant interaction between age and multimorbidity; however, there was an elevation of risk of MCI with both increasing age and multimorbidity, and a strong joint effect of having both. Compared to 70–79 year-olds without multimorbidity estimates of risk were as follows: HR = 1.38 (95%CI 0.94–2.02) for ages 70–79 with multimorbidity; HR = 2.67, (95%CI 1.58–4.49) for ages 80+ without multimorbidity, and HR = 3.35 (95%CI 2.31–4.88) for ages 80+ with multimorbidity.

In secondary analyses, we defined multimorbidity as a time dependent variable taking into consideration chronic conditions that developed during the follow-up period and explored the association of multimorbidity with incident MCI/dementia. The HR was somewhat attenuated with a wider confidence interval (HR: 1.21, 95%CI: 0.85–1.73). This may have occurred due to loss of power since 63.4% of subjects in the reference group developed multimorbidity during follow-up.

Lastly, we identified the most frequent co-occurring chronic condition pairs (dyads) among individuals with multimorbidity. Overall, there were 131 different dyads. The top five most common dyads were: hypertension (HTN) and hyperlipidemia (LIP) (n=1096; 50.4%), HTN and arthritis (ART) (n=717; 32.9%), LIP and ART (n=667; 30.7%), coronary artery disease (CAD) and LIP (n=599; 27.5) and HTN and CAD (n=555; 25.5%). In both sexes combined, the risk of MCI was significantly elevated with the presence of each of the most common dyads regardless of the other chronic conditions that were present (Table 4). In men, risk estimates for the dyads were highest for CAD and LIP (HR, 1.75; p = 0.01) and lowest for HTN and cancer (HR, 1.47; p = 0.09). Risk estimates for women ranged between 1.26 and 1.37, but none reached statistical significance.

Table 4.

Association of Chronic Disease Dyads with Incident MCI or Dementia, Overall and by Sex

| N | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dyadsa | At Risk | Events | HR (95% CI)b | P-Value |

| Total sample | ||||

| HTN & LIP | 1388 | 385 | 1.50 (1.13, 1.99) | 0.005 |

| HTN & ART | 1009 | 284 | 1.54 (1.15, 1.07) | 0.004 |

| LIP & ART | 959 | 261 | 1.58 (1.18, 2.13) | 0.002 |

| CAD & LIP | 891 | 246 | 1.56 (1.15, 2.10) | 0.004 |

| HTN & CAD | 847 | 229 | 1.51 (1.11, 2.05) | 0.009 |

| Men | ||||

| HTN & LIP | 714 | 184 | 1.60 (1.04, 2.44) | 0.03 |

| HTN & CAN | 468 | 111 | 1.47 (0.94, 2.31) | 0.09 |

| LIP & CAN | 465 | 113 | 1.61 (1.20, 2.23) | 0.04 |

| CAD & LIP | 541 | 151 | 1.75 (1.13, 2.70) | 0.01 |

| HTN & CAD | 506 | 137 | 1.67 (1.70, 2.59) | 0.02 |

| Women | ||||

| HTN & LIP | 674 | 201 | 1.37 (0.93, 2.01) | 0.11 |

| HTN & ART | 563 | 162 | 1.28 (0.86, 1.91) | 0.22 |

| LIP & ART | 511 | 141 | 1.33 (0.89, 2.01) | 0.17 |

| HTN & OST | 408 | 122 | 1.28 (0.84, 1.95) | 0.26 |

| HTN & DIA | 401 | 107 | 1.26 (0.83, 1.92) | 0.28 |

Abbreviations: HTN, hypertension; LIP, hyperlipidemia; ART, Arthritis; CAD, coronary artery disease; CAN, cancer; DIA, diabetes; OST, osteoporosis.

Most common pairs of chronic conditions that were simultaneously present for persons with 2 or more chronic conditions.

HR (95% CI), hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) from Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for sex (where applicable) and years of education using age as the time scale. Reference group were people who had 0–1 chronic conditions.

DISCUSSION

In this population-based prospective cohort of cognitively normal elderly persons, we observed a high frequency of multimorbidity in elderly persons and a significant association between multimorbidity and increased risk of MCI or dementia. The risk was higher for persons with four or more chronic conditions. In addition, the risk estimates were elevated in both men and women, but the HR was stronger in men and statistically significant only in men. The findings emphasize the importance of preventing and effectively managing chronic diseases. They provide added insights into contributors of risk for MCI and dementia, are consistent with the hypothesis that multiple etiologies may contribute to MCI and late-life dementia, and have important implications for health care planning and for developing strategies to reduce the burden of MCI and dementia.

The majority of participants had multimorbidity (86.6%), which is in accordance with other studies1, 22 and in Olmsted County, MN in particular.22 Our initial objective was to assess the association of multimorbidity at baseline as a predictor of MCI. Our hypothesis was that longstanding chronic conditions could have subclinical and detrimental effects on brain pathology prior to diagnosis of MCI. However, subsequent comorbidity during follow-up could impact MCI risk. Our secondary analyses taking incident multimorbidity into account also resulted in an elevated risk estimate. However, the confidence interval included 1, likely due to reduced power from the smaller sample size of the reference group and shorter duration of follow-up subsequent to incident multimorbidity in that group. Regardless, our findings suggest that multimorbidity at older ages increases risk of cognitive decline, but longer duration of chronic disease may have a stronger impact on this decline.

We did not specifically investigate the mechanisms of action. However, there are several potential etiologic mechanisms that may explain the association of multimorbidity with cognitive impairment. A key potential mechanism is through cardiovascular diseases: hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and cardiac diseases, specifically coronary artery disease. A second potential mechanism is aging, an important risk factor for many chronic diseases in the elderly. Indeed, the HR was 3.35 in persons 80 years and older with multimorbidity, but only 1.38 in 70–79 year olds with multimorbidity. Aging and age-related conditions may also co-occur with true etiologic risk factors to enhance the adverse effects of those risk factors. Consistent with this, hypertension co-occurred with arthritis as one of the top most frequent dyads. The development of arthritis with ageing may impair mobility in elderly persons, reduce the frequency of exercise, physical activity, and possibly increase obesity, and thereby increase the risk of both cardiovascular disease and MCI.23–26

A third potential mechanism is the presence of two or more chronic conditions that independently or combined could synergistically promote or accelerate cognitive decline. For example, heart disease is a risk factor for both overt and subclinical cerebrovascular disease, and presence of both conditions may have worse effects on risk of cognitive impairment than presence of just one.27,28,29 A recent study suggests that cardiovascular disease is also an important risk factor for arthritis.30 Thus, the combined presence of cardiac disease and arthritis may act synergistically to increase or accelerate the risk of MCI. On the other hand, a condition may not necessarily be an established risk factor for MCI, but in combination with a risk factor, may increase the risk of MCI. For example one study reported that several conditions that are not known risk factors for MCI or dementia, contributed to a high frailty index, which in turn, was associated with an increased risk of dementia.31 This suggests that a high burden of illness may increase the risk of cognitive impairment, and improving overall health might have a beneficial effect on the burden of late-life cognitive impairment or dementia.31

Finally, use of multiple prescription medications in persons with multimorbidity may contribute to risk of MCI and dementia. Clinical guidelines typically focus on a single disease, and adherence to these guidelines could result in adverse interactions between drugs and diseases.32 Failure to optimally manage specific chronic conditions (e.g. cardiovascular diseases or diabetes mellitus), or to take into account the different medications used in treatment of these conditions in an individual, could contribute to risk of cognitive impairment.33, 34

Our findings are consistent with studies showing associations of several chronic diseases with cognitive decline and impairment. Specifically, previous research in the MCSA shows that chronic diseases such as cardiac diseases,35 type 2 diabetes,36 cerebrovascular disease,37 depression,38 and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease39 are risk factors for MCI. Several of these chronic conditions are established risk factors for dementia (e.g., hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes)40, 41 and for MCI,42 and included in multimorbidity in the present study.

Other studies have also reported similar associations of chronic conditions with cognitive impairment or dementia. Comorbidity was associated with faster cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) patients43 and was cross-sectionally associated with greater AD severity.44 In addition, persons with “cognitive impairment, no dementia” (CIND) and dementia were reported to have more serious comorbidities compared to cognitively normal individuals and the severity of comorbidity was associated with worse daily functioning and cognition.45 In another study, multimorbidity was significantly associated with accelerated decline in daily functioning in dementia cases compared to non-demented individuals.46 Effects of multimorbidity on functioning in dementia patients could result in greater disability than expected, possibly due to disturbances in normal compensatory physiologic mechanisms.47

The sex difference indicating a stronger association of multimorbidity with incident MCI/dementia in men may be due to effect modification since the frequency of multimorbidity was similar in men and women. Men may have more severe comorbidity at enrollment, longer duration of comorbidity, or the effects of comorbidity on brain pathology leading to MCI risk may differ in men vs. women. Other studies have suggested sex differences in risk factors and health outcomes, such as in cardiovascular diseases48, 49 with younger age at the time of myocardial infarction or stroke among men compared to women.

The study has certain potential limitations. One limitation is the potential misclassification due to use of ICD-9 codes to define chronic conditions. To obviate this, we required two ICD9 codes for a given condition separated by more than 30 days within the 5-year capture frame. We had limited power for subgroup analyses by sex, but a longer period of follow-up and a greater number of MCI and dementia events should increase the power and precision of our estimates. Finally, study participants were primarily Caucasian, thus caution should be used in generalizing findings to ethnicities not represented in the current study. The findings, however, suggest a hypothesis for investigation in other ethnicities.

The current study has several strengths. The MCSA is a large, prospective population-based study. Participants undergo a comprehensive evaluation by three independent evaluators to assess MCI or dementia by a consensus decision. The evaluators at follow-up are blinded to previous clinical findings; this reduces misclassification and diagnostic bias and enhances the internal validity of the study findings. The ability of the REP to capture medical information for all Olmsted County residents who receive care within the county, with >90% of persons 70 years and older returning in a 3-year period, is an important strength that results in excellent ascertainment of multimorbidity over time.20 The use of the REP medical records linkage system to identify relevant ICD-9 codes of all chronic conditions within 5 years of enrollment reduced the temporal ambiguity in diagnoses, and allowed us to prospectively examine the association between multimorbidity and MCI/dementia. In addition, data on chronic conditions were prospectively identified from ongoing medical care, and therefore potentially eliminated recall bias.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the study participants and the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging team (coordinators, psychometrists, psychologists, program management team, and physicians) for their help in conducting this study and Ms. Sondra Buehler for her administrative assistance.

The study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants U01 AG006786, K01 AG028573, P50 AG016574, K01 MH068351; by the Robert H. and Clarice Smith and Abigail van Buren Alzheimer’s Disease Research Program and was made possible by the Rochester Epidemiology Project (R01AG034676). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Michelle M. Mielke has served as a consultant for Eli Lilly and Abbvie. David S. Knopman serves as Deputy Editor for Neurology®; serves on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals and for the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment Unit. He has served on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Lilly Pharmaceuticals; served as a consultant to Tau RX; and was an investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Baxter and Elan Pharmaceuticals in the past 2 years. Ronald C. Petersen serves on data monitoring committees for Pfizer Inc. and Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy, and is a consultant for Merck Inc., Roche Inc., Genentech Inc.; and receives royalties from Mild Cognitive Impairment (Oxford University Press, 2003).

Michelle M. Mielke has served as a consultant for Eli Lilly and Abbvie. David S. Knopman serves as Deputy Editor for Neurology®; serves on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals and for the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment Unit. He has served on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Lilly Pharmaceuticals; served as a consultant to Tau RX; and was an investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Baxter and Elan Pharmaceuticals in the past 2 years. Ronald C. Petersen serves on data monitoring committees for Pfizer Inc. and Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy, and is a consultant for Merck Inc., Roche Inc., Genentech Inc.; and receives royalties from Mild Cognitive Impairment (Oxford University Press, 2003).

Sponsor’s Role: The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Maria Vassilaki, Jeremiah A. Aakre, Ruth H. Cha, Walter Kremers, Jennifer L. St. Sauver, Mary M. Machulda, Yonas E. Geda, and Rosebud O. Roberts report no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

Author Contributions: R Roberts had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. R Roberts, J St. Sauver, D Knopman, R Petersen and M Vassilaki conceived and designed the study. R Petersen, M Vassilaki, D Knopman and R Roberts acquired the data. M Vassilaki, J. Aakre, R Cha, W. Kremers and R Roberts analyzed and interpreted the data. M Vassilaki and R Roberts drafted the manuscript. M Vassilaki, R Cha, J St. Sauver, M Mielke, Y Geda, M Machulda, R Petersen and R Roberts provided critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. R Cha and R Roberts contributed to the statistical analysis. R Roberts and R Petersen obtained the funding. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript before submission and will approve the final version to be published.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, et al. Aging with multimorbidity: A systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10:430–439. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salisbury C. Multimorbidity: Redesigning health care for people who use it. Lancet. 2012;380:7–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60482-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruel G, Levesque JF, Stocks N, et al. Understanding the evolution of multimorbidity: evidences from the North West Adelaide Health Longitudinal Study (NWAHS) Plos One. 2014;9:e96291. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Violan C, Foguet-Boreu Q, Flores-Mateo G, et al. Prevalence, determinants and patterns of multimorbidity in primary care: A systematic review of observational studies. Plos One. 2014;9:e102149. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Mielke MM, et al. Higher risk of progression to dementia in mild cognitive impairment cases who revert to normal. Neurology. 2014;82:317–325. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manly JJ, Tang MX, Schupf N, et al. Frequency and course of mild cognitive impairment in a multiethnic community. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:494–506. doi: 10.1002/ana.21326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ravaglia G, Forti P, Montesi F, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: epidemiology and dementia risk in an elderly Italian population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmer K, Backman L, Winblad B, et al. Mild cognitive impairment in the general population: Occurrence and progression to Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:603–611. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181753a64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts RO, Geda YE, Knopman DS, et al. The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging: design and sampling, participation, baseline measures and sample characteristics. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;30:58–69. doi: 10.1159/000115751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petersen RC, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, et al. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment is higher in men the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Neurology. 2010;75:889–897. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f11d85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, et al. Use of a medical records linkage system to enumerate a dynamic population over time: The Rochester Epidemiology Project. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:1059–1068. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH, Jr, et al. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol. 1982;37:323–329. doi: 10.1093/geronj/37.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kokmen E, Smith GE, Petersen RC, et al. The short test of mental status. Correlations with standardized psychometric testing. Arch Neurol. 1991;48:725–728. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1991.00530190071018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ivnik RJMJ, Smith GE, et al. Mayo’s Older Americans Normative Studies: WAIS-R norms for ages 56 to 97. Clin Neuropsychol. 1992;6(suppl 001):1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256:183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Ed 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Welsh KA, Breitner JCS, Magruder-Habib KM. Detection of Dementia in the Elderly Using Telephone Screening of Cognitive Status. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 1993;6:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Ketchel P, et al. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12:233–239. doi: 10.1176/jnp.12.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, et al. Data resource profile: The Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) medical records-linkage system. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1614–1624. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodman RA, Posner SF, Huang ES, et al. Defining and measuring chronic conditions: imperatives for research, policy, program, and practice. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E66. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rocca WA, Boyd CM, Grossardt BR, et al. Prevalence of multimorbidity in a geographically defined american population: Patterns by age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:1336–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geda YE, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, et al. Physical exercise, aging, and mild cognitive impairment: A population-based study. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:80–86. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lautenschlager NT, Cox K, Cyarto EV. The influence of exercise on brain aging and dementia. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:474–481. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahlskog JE, Geda YE, Graff-Radford NR, et al. Physical exercise as a preventive or disease-modifying treatment of dementia and brain aging. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:876–884. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2011.0252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xanthakis V, Enserro DM, Murabito JM, et al. Ideal cardiovascular health: associations with biomarkers and subclinical disease, and impact on incidence of cardiovascular disease in the Framingham Offspring Study. Circulation. 2014;130:1676–1683. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts RO, Geda YE, Knopman DS, et al. Cardiac disease associated with increased risk of nonamnestic cognitive impairment: Stronger effect on women. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:374–382. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yaffe K, Laffan AM, Harrison SL, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing, hypoxia, and risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in older women. JAMA. 2011;306:613–619. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iadecola C. The overlap between neurodegenerative and vascular factors in the pathogenesis of dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120:287–296. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0718-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li C, Liu T, Sun W, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of arthritis in a middle-aged and older Chinese population: The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Rheumatology. 2015;54:697–706. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song X, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Nontraditional risk factors combine to predict Alzheimer disease and dementia. Neurology. 2011;77:227–234. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318225c6bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: Implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294:716–724. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalisch Ellett LM, Pratt NL, Ramsay EN, et al. Multiple anticholinergic medication use and risk of hospital admission for confusion or dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1916–1922. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirkpatrick AC, Vincent AS, Guthery L, et al. Cognitive impairment is associated with medication nonadherence in asymptomatic carotid stenosis. Am J Med. 2014;127:1243–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts R, Knopman DS. Classification and epidemiology of MCI. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29:753–772. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Geda YE, et al. Association of diabetes with amnestic and nonamnestic mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kornerup H, Osler M, Boysen G, et al. Major life events increase the risk of stroke but not of myocardial infarction: Results from the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010;17:113–118. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3283359c18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Geda YE, Roberts RO, Mielke MM, et al. Baseline neuropsychiatric symptoms and the risk of incident mild cognitive impairment: A population-based study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:572–581. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13060821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh B, Mielke MM, Parsaik AK, et al. A Prospective study of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the risk for mild cognitive impairment. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:581–588. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Imtiaz B, Tolppanen AM, Kivipelto M, et al. Future directions in Alzheimer's disease from risk factors to prevention. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;88:661–670. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reitz C, Mayeux R. Alzheimer disease: Epidemiology, diagnostic criteria, risk factors and biomarkers. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;88:640–651. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ganguli M, Fu B, Snitz BE, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: Incidence and vascular risk factors in a population-based cohort. Neurology. 2013;80:2112–2120. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318295d776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Solomon A, Dobranici L, Kareholt I, et al. Comorbidity and the rate of cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:1244–1251. doi: 10.1002/gps.2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doraiswamy PM, Leon J, Cummings JL, et al. Prevalence and impact of medical comorbidity in Alzheimer's disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57:M173–M177. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.3.m173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lyketsos CG, Toone L, Tschanz J, et al. Population-based study of medical comorbidity in early dementia and "cognitive impairment, no dementia (CIND)": Association with functional and cognitive impairment: The Cache County Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:656–664. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.8.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Melis RJF, Marengoni A, Rizzuto D, et al. The Influence of multimorbidity on clinical progression of dementia in a population-based cohort. Plos One. 2013;8:e84014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Colon-Emeric CS, Whitson HE, Pavon J, et al. Functional decline in older adults. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:388–394. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gerber Y, Weston SA, Killian JM, et al. Sex and classic risk factors after myocardial infarction: A community study. Am Heart J. 2006;152:461–468. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Petrea RE, Beiser AS, Seshadri S, et al. Gender differences in stroke incidence and poststroke disability in the Framingham heart study. Stroke. 2009;40:1032–1037. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.542894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]