Identity

| Other names | LAM |

| Note | Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a multi-system disease, affecting predominantly pre-menopausal women, that is characterized by proliferation of abnormal smooth muscle-like cells (LAM cells) leading to the formation of lung cysts, fluid-filled cystic tumors in the axial lymphatics (e.g., lymphangioleiomyomas), and abdominal tumors, primarily in the kidneys, comprising adipose cells, vascular structures and LAM cells (e.g., angiomyolipomas). |

Clinics and Pathology

| Disease | Pulmonary disease |

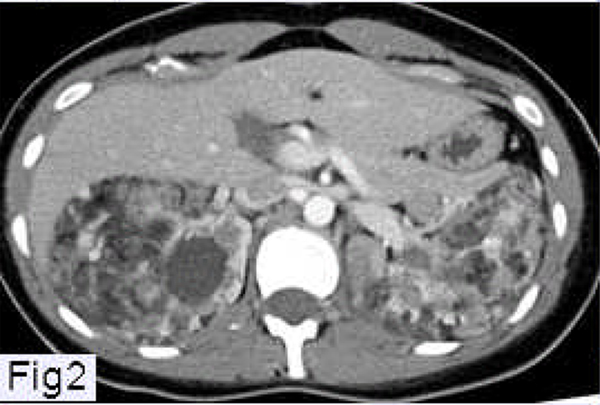

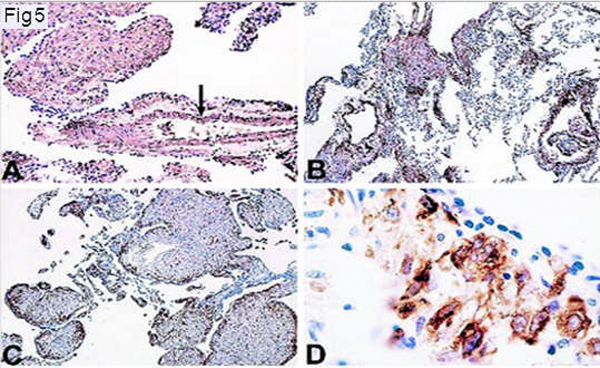

| Note | Pulmonary disease is the main cause of morbidity and mortality. LAM usually presents with progressive breathlessness or with spontaneous recurrent pneumothorax, chylous effusions (chylothorax and ascites), or hemorrhage within an angiomyolipoma. Computed tomography scans show numerous thin-walled cysts throughout the lungs (Figure 1A and 1B), renal angiomyolipomas (Figure 2), and lymphangioleiomyomas (Figure 3). Pulmonary function abnormalities include airflow obstruction and gas exchange abnormalities. Lung lesions in LAM are characterized by nodular infiltrates and clusters of LAM cells near cystic lesions and along pulmonary blood vessels, lymphatics, and bronchioles (Figure 4A and 4B). Two types of LAM cells have been described: small spindle-shaped cells and larger, epithelioid-like cells with abundant cytoplasm. Both types of cells react with antibodies against smooth muscle cell-specific antigens (e.g., smooth muscle a-actin, vimentin, desmin) (Figure 5). The epithelioid LAM cells react with HMB-45, a monoclonal antibody that recognizes gp100, a premelanosomal protein (Figures 5, 6 and 7). The spindle-shaped cells are more likely to react with anti-proliferation cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) antibodies, suggesting a more proliferative state. Receptors for estrogen, progesterone, and growth factors have been identified in LAM cells. LAM cells appear to have neoplastic properties and may be capable of metastasis. In addition to their presence in lungs, lymphatics and kidneys, LAM cells have been isolated from blood, chyle, and urine. |

| Etiology | The tumor suppressor genes TSC1 and TSC2 have been implicated in the etiology of LAM, as mutations and loss of heterozygosity in the TSC genes have been detected in LAM cells (Figure 7). TSC1 encodes hamartin, a protein that plays a role in the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton, and TSC2 encodes tuberin, a protein with roles in cell growth and proliferation. TSC1 and TSC2 may function both individually and as a cytosolic complex. |

| Epidemiology | LAM occurs in about one third of women with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by hamartoma-like tumor growths in various organs, cerebral calcifications, seizures, and mental retardation, that occurs in one of 5800 live births. Sporadic LAM is a relatively uncommon disease with a prevalence that has been estimated at 1–2.6/million women. |

| Treatment | Because LAM is predominantly a disease of pre-menopausal women and may worsen during pregnancy, or following the administration of exogenous estrogens, hormonal manipulations have been employed. However, no controlled studies have been undertaken to determine their efficacy. A retrospective study of 275 patients found no difference in disease progression between patients treated with progesterone and patients who received no progesterone. There is also no evidence that suppression of ovarian function, either by oophorectomy or use of gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogs, benefit patients with LAM. |

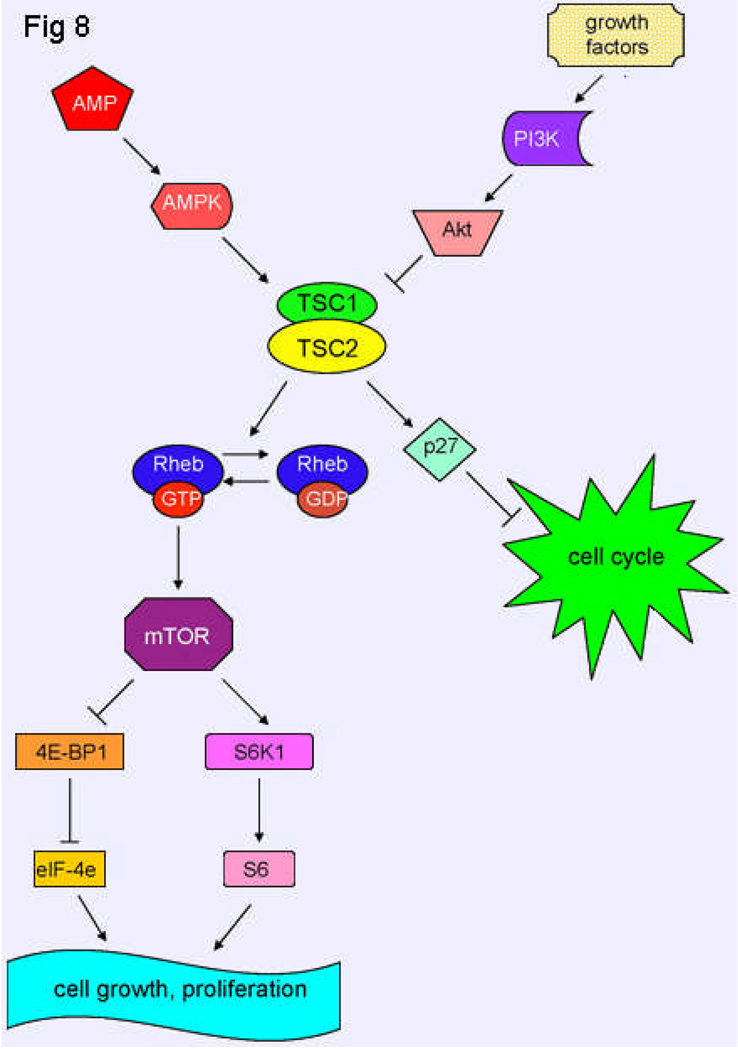

| Progress about the mechanisms regulating cell proliferation and migration, and angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis, have provided a foundation for the development of new therapies. The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) appears to play a role in regulating the growth and multiplication of LAM cells (Figure 8). An inhibitor of mTOR, sirolimus (rapamycin), an antifungal macrolide antibiotic approved for immunosuppression after solid organ transplantation, has been studied as a possible treatment for LAM. In a rat model of TSC (Eker rat) with a functionally null germline mutation of tsc2, which spontaneously develops renal cell carcinomas, treatment with sirolimus resulted in a decrease in size of kidney tumors by both a reduction in the percentage of proliferating cells, and extensive tumor cell death. An open label study with sirolimus undertaken in twenty patients with angiomyolipomas showed a reduction in tumor size to 53.2+/−26.6 % of baseline at one year. An improvement in some lung function parameters was also observed. A clinical trial [MILES trial (Multicenter International Lymphangioleiomyomatosis Efficacy of Sirolimus Trial)], to examine the effect of rapamycin on pulmonary function, is underway. | |

| Patients with severe LAM or those who show an accelerated rate of decline in lung function may be referred to a lung transplantation center. | |

| Evolution | LAM is a chronic disease, which may span decades. A retrospective analysis of 402 patients seen at NIH from 1995 to 2006 showed that 22 had died, eight of whom had undergone lung transplantation. The mortality in this large cohort was 5.5%. Of the surviving 380 patients, 38 (10%) had lung transplantation. A recent study reported a ten year survival greater than 90%. |

Figure 1.

Chest CT scan of a patient with LAM (A) showing numerous thin-walled cysts distributed throughout the lungs. (B) The lung parenchyma is almost completely replaced by very small cysts.

Figure 2.

Abdominal CT scan of a patient with LAM showing angiomyolipomas involving both kidneys.

Figure 3.

Abdominal CT scan of a patient with LAM showing a large lymphangioleiomyoma located in the retroperitoneal area and surrounding the aorta and inferior vena cava.

Figure 4.

A and B. LAM nodule comprising spindle-shaped cells and larger epithelioid cells (A). Nodules of various sizes (B) are seen in involved lung (hematoxylin-eosin; original magnification ×50).

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry of LAM cells. Immunoperoxidase method and counterstaining with hematoxylin. A and B: Immunoreactivity with a-smooth muscle actin antibodies. LAM cells show strong reactivity (A). Pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells are also strongly positive (arrow). LAM cells in the walls of the lung cysts are also strongly reactive (arrow) (B) (original magnification ×250 for each). C: Immunoreactivity with monoclonal antibody HMB-45. Immunoreactive cells are distributed in the periphery of LAM lung nodules (arrow) (original magnification ×250). D: Immunoreactivity with monoclonal antibody HMB-45. Higher-magnification view of tissue shown in C. A strong granular reaction is present in large epithelioid LAM cells adjacent to epithelial cells covering LAM lung nodules (arrow) (D) (original magnification ×1000).

Figure 6.

Left panel: close-up of LAM nodule (hematoxylin-eosin). Right panel: same nodule showing positive immunocytochemistry stain for HMB 45 (original magnification ×200).

Figure 7.

Characteristics of LAM cells (A–C). Reaction of LAM cells cultured from lung and pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASM) with monoclonal antibody against SMA (A). Reaction of cultured LAM cells and melanoma cells (MALME-3M) with monoclonal antibody HMB-45 (B). Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for TSC1 (green) and TSC2 (red) in LAM cells showing normal presence of two of each alleles as well as abnormal presence of TSC2 alleles (left) (C). FISH for TSC1 (green, arrow) and TSC2 (red, arrowhead) in LAM cell with one (right) or two TSC2 (left) alleles (C). Bar, 20 µm.

Figure 8.

Schematic model of TSC1 and TSC2 pathways. The TSC1/TSC2 complex has roles in cell cycle progression and in cell growth and proliferation. Tuberin binds p27KIP1, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, stabilizing it and resulting in inhibition of cell cycle progression. Tuberin also has Rheb GAP activity, which converts Rheb-GTP to Rheb-GDP, resulting in inactive Rheb. Rheb controls mTOR, which is a kinase that controls translation through the phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 and S6K1. Akt, when activated by growth factors, phosphorylates tuberin, leading to an inhibition of tuberin and resulting in cell growth and proliferation. However, when a state of low cellular energy exists, AMPK phosphorylates tuberin, activating it, and thereby inhibiting cell growth.

Genes involved and Proteins

| Gene Name | TSC genes |

| Note | TSC1 and TSC2 are tumor suppressor genes. TSC1 (9q34) encodes the 130kDa protein hamartin, while TSC2 (16p13.3) encodes the 200kDa protein tuberin. Hamartin and tuberin may have individual functions, but they also interact to form a cytosolic complex. Loss of heterozygosity of TSC2 has been detected in LAM lesions from lung and kidney, and mutations in TSC2 occur more frequently than those in TSC1 in patients with sporadic LAM. Hamartin may play a role in the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton, with a lack of hamartin leading to a loss of focal adhesions and detachment from substrate, resulting in cell rounding. Hamartin induces an increase in the levels of RhoGTP, an activator of ERM (ezrin-radixin-moesin) proteins, and binds to activated ERM proteins. ERM proteins bind both filamentous actin and integral membrane proteins, thereby bridging the plasma membrane and cortical actin filaments. |

| Tuberin has roles in pathways controlling cell growth and proliferation (Figure 8). It is a negative regulator of cell cycle progression, and loss of tuberin function shortens the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Tuberin binds p27KIP1, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, thereby preventing its degradation and leading to inhibition of the cell cycle. Upon mutation of tuberin, p27 becomes mislocalized in the cytoplasm, allowing the cell cycle to progress. | |

| Tuberin also integrates signals from growth factors and energy stores through its interaction with mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) (Figure 8). Tuberin has Rheb GAP (Ras homolog enriched in brain GTPase-activating protein) activity, which converts Rheb-GTP to Rheb-GDP, thereby inactivating Rheb. Rheb controls mTOR, a serine/threonine kinase that phosphorylates at least two substrates: 4E-BP1, allowing cap-dependent translation, and S6K1, leading to translation of 5' TOP (terminal oligopyrimidine tract)-containing RNAs. Phosphorylation of tuberin by Akt, which is known to be activated by growth factors, leads to inhibition of tuberin and results in cell growth and proliferation. Phosphorylation of tuberin by AMPK (AMP-activated kinase) activates tuberin and further promotes inhibition of cell growth in states of energy deprivation. Tuberin may also have roles in endocytosis through its interaction with rabaptin-5 and in transcriptional activation through interaction with members of the retinoid X receptor (RXR) family. |

Bibliography

- Berger U, Khaghani A, Pomerance A, Yacoub MH, Coombes RC. Pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis and steroid receptors. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990 May;93(5):609–614. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/93.5.609. PMID 2183584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Chromosome 16 Tuberous Sclerosis Consortium. Identification and characterization of the tuberous sclerosis gene on chromosome 16. Cell. 1993 Dec 31;75(7):1305–1315. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90618-z. PMID 8269512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucek T, Pusch O, Wienecke R, DeClue JE, Hengstschlager M. Role of the tuberous sclerosis gene-2 product in cell cycle control. Loss of the tuberous sclerosis gene-2 induces quiescent cells to enter S phase. J Biol Chem. 1997 Nov 14;272(46):29301–29308. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.29301. PMID 9361010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao G-H, Shoarinejad F, Jin F, Golemis EA, Yeung RS. The tuberous sclerosis 2 gene product, tuberin, functions as a Rab5 GTPase activating protein (GAP) in modulating endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 1997 Mar 7;272(10):6097–6100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6097. PMID 9045618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry KW, Yuan X, Koszewski NJ, Onda H, Kwiatkowski DJ, Noonan DJ. Tuberous sclerosis gene 2 product modulates transcription mediated by steroid hormone receptor family members. J Biol Chem. 1998 Aug 7;273(32):20535–20539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20535. PMID 9685410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plank TL, Yeung RS, Henske EP. Hamartin, the product of the tuberous sclerosis 1 (TSC1) gene, interacts with tuberin and appears to be localized to cytoplasmic vesicles. Cancer Res. 1998 Nov 1;58(21):4766–4770. PMID 9809973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolarek TA, Wessner LL, McCormack FX, Mylet JC, Menon AG, Henske EP. Evidence that lymphangiomyomatosis is caused by TSC2 mutations: chromosome 16p13 loss of heterozygosity in angiomyolipomas and lymph nodes from women with lymphangiomyomatosis. Am J Hum Genet. 1998 Apr;62(4):810–815. doi: 10.1086/301804. PMID 9529362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucek T, Yeung RS, Hengstschlager M. Inactivation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27 upon loss of the tuberous sclerosis complex gene-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(26):15653–15658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15653. PMID 9861025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usuki J, Horiba K, Chu SC, Moss J, Ferrans VJ. Immunohistochemical analysis of proteins of Bcl-2 family in pulmonary Lymphangioleiomyomatosis : Association of Bcl-2 expression with hormonal receptor status. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1998 Oct;122(10):895–902. PMID 9786350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Slegtenhorst M, Nellist M, Nagelkerken B, Cheadle J, Snell R, van den Ouweland A, Reuser A, Sampson J, Halley D, van der Sluijs P. Interaction between hamartin and tuberin, the TSC1 and TSC2 gene products. Hum Mol Genet. 1998 Jun;7(6):1053–1057. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.6.1053. PMID 9580671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu SC, Horiba K, Usuki J, Avila NA, Chen CC, Travis WD, Ferrans VJ, Moss J. Comprehensive evaluation of 35 patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Chest. 1999 Apr;115(4):1041–1052. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.4.1041. PMID 10208206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto Y, Horiba K, Usuki J, Chu SC, Ferrans VJ, Moss J. Markers of cell proliferation and expression of melanosomal antigen in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999 Sep;21(3):327–336. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.21.3.3693. PMID 10460750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nellist M, van Slegtenhorst MA, Goedbloed M, van den Ouweland AM, Halley DJ, van der Sluijs P. Characterization of the cytosolic tuberin-hamartin complex. J Biol Chem. 1999 Dec 10;274(50):35647–35652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.50.35647. PMID 10585443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban T, Lazor R, Lacronique J, Murris M, Labrune S, Valeyre D, Cordier JF. Pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. A study of 69 patients. Groupe d'Etudes et de Recherche sur les Maladies "Orphelines" Pulmonaires (GERM"O"P) Medicine (Baltimore) 1999 Sep;78(5):321–337. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199909000-00004. PMID 10499073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carsillo T, Astrinidis A, Henske EP. Mutations in the tuberous sclerosis complex gene TSC2 are a cause of sporadic pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000 May 23;97(11):6085–6090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.6085. PMID 10823953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello LC, Hartman TE, Ryu JH. High frequency of pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis in women with tuberous sclerosis complex. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000 Jun;75(6):591–594. doi: 10.4065/75.6.591. PMID 10852420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb RF, Roy C, Diefenbach TJ, Vinters HV, Johnson MW, Jay DG, Hall A. The TSC1 tumour suppressor hamartin regulates cell adhesion through ERM proteins and the GTPase Rho. Nat Cell Biol. 2000 May;2(5):281–287. doi: 10.1038/35010550. PMID 10806479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz DN, Brody A, Meyer C, Leonard J, Chuck G, Dabora S, Sethuraman G, Colby TV, Kwiatkowski DJ, McCormack FX. Mutational and radiographic analysis of pulmonary disease consistent with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia in women with tuberous sclerosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001 Aug 15;164(4):661–668. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.2011025. PMID 11520734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama H, Ohbayashi C, Hino O, Tsutsumi M, Konishi Y. Pathogenesis of multifocal micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia and lymphangioleiomyomatosis in tuberous sclerosis and association with tuberous sclerosis gene TSC1 and TSC2. Pathol Int. 2001 Aug;51(8):585–594. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2001.01242.x. PMID 11564212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss J, Avila NA, Barnes PM, Litzenberger RA, Bechle J, Brooks PG, Hedin CJ, Hunsberger S, Kristof AS. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001 Aug 15;164(4):669–671. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.2101154. PMID 11520735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucek T, Rosner M, Miloloza A, Kubista M, Cheadle JP, Sampson JR, Hengstschlager M. Tuberous sclerosis causing mutants of the TSC2 gene product affect proliferation and p27 expression. Oncogene. 2001 Aug 9;20(35):4904–4909. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204627. PMID 11521203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strizheva GD, Carsillo T, Kruger WD, Sullivan EJ, Ryu JH, Henske EP. The spectrum of mutations in TSC1 and TSC2 in women with tuberous sclerosis and lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001 Jan;163(1):253–258. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2005004. PMID 11208653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Zhang Y, Arrazola P, Hino O, Kobayashi T, Yeung RS, Ru B, Pan D. TSC tumour suppressor proteins antagonize amino-acid-TOR signaling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002 Sep;4(9):699–704. doi: 10.1038/ncb847. PMID 12172555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncharova EA, Goncharov DA, Eszterhas A, Hunter DS, Glassberg MK, Yeung RS, Walker CL, Noonan D, Kwiatkowski DJ, Chou MM, Panettieri RA, Jr, Krymskaya VP. Tuberin regulates p70 S6 kinase activation and ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation: a role for the TSC2 tumor suppressor gene in pulmonary lymphangioleimyomatosis (LAM) J Biol Chem. 2002 Aug 23;277(34):30958–30967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202678200. Epub 2002 Jun 3. PMID 12045200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Guan KL. TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signaling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002 Sep;4(9):648–657. doi: 10.1038/ncb839. PMID 12172553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning BD, Tee AR, Logsdon MN, Blenis J, Cantley LC. Identification of tuberous sclerosis complex-2 tumor suppressor gene product tuberin as a target of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway. Mol Cell. 2002 Jul;10(1):151–162. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00568-3. PMID 12150915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tee AR, Fingar DC, Manning BD, Kwiatkowski DJ, Cantley LC, Blenis J. Tuberous sclerosis complex-1 and -2 gene products function together to inhibit mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-mediated downstream signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002 Oct 15;99(21):13571–13576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202476899. Epub 2002 Sep 23. PMID 12271141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittmann I, Rolf B, Amann G, Lohrs U. Recurrence of lymphangioleiomyomatosis after single lung transplantation: new insights into pathogenesis. Hum Pathol. 2003 Jan;34(1):95–98. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2003.50. PMID 12605373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro AF, Rebhun JF, Clark GJ, Quilliam LA. Rheb binds tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2) and promotes S6 kinase activation in a rapamycin- and farnesylation-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2003 Aug 29;278(35):32493–32496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300226200. Epub 2003 Jul 3. PMID 12842888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K, Zhu T, Guan KL. TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell. 2003 Nov 26;115(5):577–590. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00929-2. PMID 14651849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karbowniczek M, Astrinidis A, Balsara BR, Testa JR, Lium JH, Colby TV, McCormack FX, Henske EP. Recurrent lymphangiomyomatosis after transplantation: Genetic analyses reveal a metastatic mechanism. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003 Apr 1;167(7):976–982. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200208-969OC. Epub 2002 Oct 31. PMID 12411287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karbowniczek M, Yu J, Henske EP. Renal angiomyolipomas from patients with sporadic lymphangiomyomatosis contain both neoplastic and non-neoplastic vascular structures. Am J Pathol. 2003 Feb;162(2):491–500. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63843-6. PMID 12547707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krymskaya VP. Tumour suppressors hamartin and tuberin: intracellular signaling. Cell Signal. 2003 Aug;15(8):729–739. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(03)00040-8. PMID 12781866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tee AR, Manning BD, Roux PP, Cantley LC, Blenis J. Tuberous sclerosis complex gene products, tuberin and hamartin, control mTOR signaling by acting as a GTPase-activating protein complex toward Rheb. Curr Biol. 2003 Aug 5;13(15):1259–1268. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00506-2. PMID 12906785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Gao X, Saucedo LJ, Ru B, Edgar BA, Pan D. Rheb is a direct target of the tuberous sclerosis tumour suppressor proteins. Nat Cell Biol. 2003 Jun;5(6):578–581. doi: 10.1038/ncb999. PMID 12771962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks DM, Pacheco-Rodriguez G, DeCastro RM, McCoy JP, Jr, Wang JA, Kumaki F, Darling T, Moss J. Molecular and genetic analysis of disseminated neoplastic cells in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Dec 14;101(50):17462–17467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407971101. Epub 2004 Dec 6. PMID 15583138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Corradetti MN, Inoki K, Guan KL. TSC2: filling the GAP in the mTOR signaling pathway. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004 Jan;29(1):32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.11.007. PMID 14729330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner M, Freilinger A, Hengstschlager M. Proteins interacting with the tuberous sclerosis gene products. Amino Acids. 2004 Oct;27(2):119–128. doi: 10.1007/s00726-004-0119-z. Epub 2004 Sep 7. PMID 15351877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner M, Hengstschlager M. Tuberin binds p27 and negatively regulates its interaction with the SCF component Skp2. J Biol Chem. 2004 Nov 19;279(47):48707–48715. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405528200. Epub 2004 Sep 8. PMID 15355997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K, Corradetti MN, Guan KL. Dysregulation of the TSC-mTOR pathway in human disease. Nat Genet. 2005 Jan;37(1):19–24. doi: 10.1038/ng1494. PMID 15624019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steagall WK, Taveira-DaSilva AM, Moss J. Clinical and molecular insights into lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2005 Dec;22(Suppl 1):S49–S66. (Review). PMID 16457017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SR. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Eur Respir J. 2006 May;27(5):1056–1065. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00113303. (Review). PMID 16707400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu JH, Moss J, Beck GJ, Lee JC, Brown KK, Chapman JT, Finlay GA, Olson EJ, Ruoss SJ, Maurer JR, Raffin TA, Peavy HH, McCarthy K, Taveira-Dasilva A, McCormack FX, Avila NA, Decastro RM, Jacobs SS, Stylianou M, Fanburg BL NHLBI LAM Registry Group. The NHLBI Lymphangioleiomyomatosis Registry : Characteristics of 230 Patients at Enrollment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006 Jan 1;173(1):105–111. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1298OC. Epub 2005 Oct 6. PMID 16210669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taveira-DaSilva AM, Steagall WK, Moss J. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Cancer Control. 2006 Oct;13(4):276–258. doi: 10.1177/107327480601300405. (Review) PMID 17075565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harari S, Cassandro R, Chiodini J, Taveira-DaSilva AM, Moss J. Effect of a gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogue on lung function in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Chest. 2008 Feb;133(2):448–454. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2277. Epub 2007 Dec 10. PMID 18071009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco-Rodriguez G, Steagall WK, Crooks DM, Stevens LA, Hashimoto H, Li S, Wang JA, Darling TN, Moss J. TSC2 loss in lymphangioleiomyomatosis cells correlated with expression of CD44v6, a molecular determinant of metastasis. Cancer Res. 2007 Nov 1;67(21):10573–10581. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1356. PMID 17975002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steagall WK, Glasgow CG, Hathaway OM, Avila NA, Taveira-Dasilva AM, Rabel A, Stylianou MP, Lin JP, Chen X, Moss J. Genetic and morphologic determinants of pneumothorax in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007 Sep;293(3):L800–L808. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00176.2007. Epub 2007 Jul 6. PMID 17616646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow CG, Taveira-Dasilva AM, Darling TN, Moss J. Lymphatic involvement in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1131:206–214. doi: 10.1196/annals.1413.018. (Review). PMID 18519973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack FX. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. A clinical update. Chest. 2008 Feb;133(2):507–516. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0898. (Review). PMID 18252917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner M, Hanneder M, Siegel N, Valli A, Hengstschlger M. The tuberous sclerosis gene products hamartin and tuberin are multifunctional proteins with a wide spectrum of interacting partners. Mutat Res. 2008 Mar-Apr;658(3):234–246. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.01.001. Epub 2008 Jan 12. PMID 18291711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]