Abstract

Sorafenib is the first-line treatment of choice for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, the benefits of sorafenib in HCC patients with portal vein tumour thrombosis (PVTT) remain uncertain. Until now, a total of eight comparative studies have been identified for this systematic review. Four retrospective studies showed that hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy, hepatic resection, and three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy might be superior to sorafenib in improving the overall survival. Two ongoing randomised controlled trials (RCTs) will compare the outcomes of transarterial chemoembolisation or radioembolisation with those of sorafenib for the treatment of HCC with PVTT. In addition, two completed RCTs found that additional use of cryotherapy or radiofrequency ablation could prolong the survival of patients receiving sorafenib. In conclusion, the clinical efficacy of sorafenib in HCC patients with PVTT has been widely challenged by other interventions. However, further well-designed RCTs are necessary to confirm the findings of retrospective analyses. Cryotherapy or radiofrequency ablation may be considered as an adjunctive therapy in such patients, if sorafenib is prescribed.

Keywords: sorafenib, hepatocellular carcinoma, portal vein tumour thrombosis, radiofrequency ablation, cryotherapy, transarterial chemoembolization, radioembolisation, radiotherapy

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third most common cause of cancer-related death [1]. The presence of portal vein tumour thrombosis (PVTT) is regarded as one of the most important prognostic factors in HCC patients [2]. However, there is no consensus about the treatment of HCC with PVTT. According to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system [3], HCC patients with PVTT should be at the advanced stage, and in whom sorafenib should be recommended as the first-line treatment modality. This recommendation is primarily based on the results of two randomised, double-blinded, controlled trials, which showed that the use of sorafenib can achieve a significant survival benefit in patients with advanced HCC [4, 5]. Notably, in the two randomised controlled trials (RCTs), only 30–40% of patients had macroscopic vascular invasion, and the site of vascular invasion was unclear. In the SHARP trial by Llovet et al., 36% and 41% of patients receiving sorafenib and placebo had macroscopic vascular invasion, respectively. In the ORIENTAL trial by Cheng et al., 36% and 34.2% of patients receiving sorafenib and placebo had macroscopic vascular invasion, respectively. In addition, scatter case reports suggested that complete portal vein recanalisation could develop after sorafenib in HCC patients with PVTT [6–9]. However, the benefits of sorafenib in HCC patients with PVTT have been questioned because the presence of PVTT significantly decreases the survival of HCC patients receiving sorafenib [10–13]. On the other hand, until now, the role of other alternative treatment modalities versus sorafenib in such patients remains unclear. Considering that the knowledge is needed to guide the clinical decisions, we have conducted a systematic review of available studies comparing the efficacy of sorafenib versus other interventions in HCC patients with PVTT.

Literature search and identification

The PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane library databases were searched for the retrieval of all relevant papers. In addition, the official website www.ClinicalTrials.gov was searched for the retrieval of all ongoing trials. The search items used were: “sorafenib” and “hepatocellular carcinoma” and “portal vein thrombosis”. No limitations were specified for the publication language or status. Comparative studies were included if they performed a head-to-head comparison between sorafenib monotherapy and other interventions or a comparison between sorafenib alone versus combined with other interventions for the treatment of HCC with PVTT. Considering the heterogeneity of the study population and treatment modalities, we did not perform any meta-analyses.

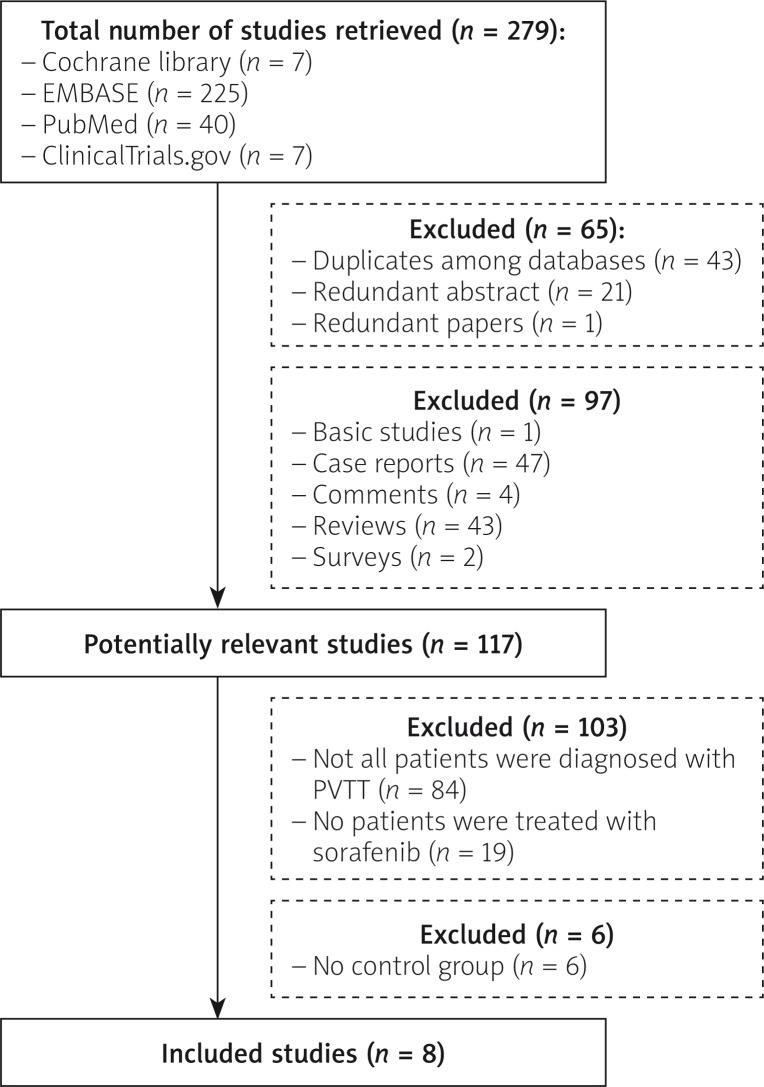

A total of 272 papers and six trials were identified. Finally, eight comparative studies were eligible for systematic review (Figure 1) [14–21]. Characteristics and eligibility criteria of these included studies are described in Tables I and II, respectively.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study inclusion

Table I.

Characteristics of included studies: an overview of comparative studies

| First author (year) | Enrolment period | Countries | Study design | Patients | Comparison groups | No. total patients | End-point |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giorgio (2011) | NA | Italy | RCT (abstract) | HCC, liver cirrhosis, Child-Pugh A, PVTT | Sorafenib alone vs. sorafenib + RFA | 79 | 3-year survival rate |

| Kasai (2013) | NA | Japan | Retrospective study (abstract) | HCC, PVTT | Sorafenib alone vs. HAIC of 5-fluorouracil + systemic pegylated interferon α2b | 40 | Early response rate; cumulative survival rate |

| Lee (2014) | 01.2000–12.2012 | South Korea | Retrospective study (abstract) | HCC, PVTT | Sorafenib alone vs. hepatic resection vs. TACE | 173 | Survival time; 1-, 2-, and 3-year overall survival rate |

| Nakazawa (2014) | 07.2009–11.2011 | Japan | Retrospective propensity score analysis (full text) | Unresectable HCC, PVTT in the main trunk or the first branch | Sorafenib alone vs. radiotherapy | 97 | The primary end point was all-cause mortality |

| Sinclair (2014) | Ongoing | Multi-national | Phase III, two-arm, open-label, RCT (abstract) | Unresectable HCC, PVTT | Sorafenib alone vs. yttrium-90 glass microspheres | 328 | Primary endpoint: overall survival from the time of randomisation until time of event (death). Secondary endpoint: time to progression/symptomatic progression, time to worsening of PVT, tumour response, patient-reported outcome assessments, and adverse events |

| Song (2014) | 02.2008–05.2013 | South Korea | Retrospective study (full text) | Advanced HCC, PVTT | Sorafenib alone vs. HAIC | 110 | Disease control rate; objective response rate; overall survival; time to progression |

| Yang (2012) | 07.2008–07.2010 | China | RCT (full text) | HCC, Child-Pugh A or B, PVTT | Sorafenib alone vs. sorafenib + cryotherapy | 104 | Primary end-point: overall survival. Secondary end-point: time to progression, tolerability |

| Yoon (2013) | Ongoing | South Korea | Phase II RCT (abstract) | HCC, major branch of portal vein invasion, Child-Pugh score ≤ 7 | Sorafenib alone vs. TACE | 40 | Primary end-point: time to progression. Secondary end-point: overall survival, objective tumour response/control rate, progression-free survival, change of perfusion parameter, α fetoprotein responsiveness |

HAIC – Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy, HCC – hepatocellular carcinoma, PVTT – portal vein tumour thrombus, RCT – randomised controlled trial, RFA – radiofrequency ablation, TACE – transarterial chemoembolisation.

Table II.

Eligibility criteria: an overview of published comparative studies

| First author (year) | Eligibility criteria |

|---|---|

| Giorgio (2011) | Inclusion criteria: single HCC (≤ 6.5 cm) and PVTT; or 3 HCC nodules ≤ 5 cm with PVTT |

| Kasai (2013) | Inclusion criteria: advanced HCC patients with PVTT |

| Lee (2014) | Inclusion criteria: advanced HCC patients with PVTT |

| Exclusion criteria: main portal vein tumour thrombosis, superior mesenteric vein tumour thrombosis, or Child-Pugh C | |

| Nakazawa (2014) | Inclusion criteria for sorafenib: (1) unresectable advanced HCC without HCC rupture; (2) no effect of TACE; (3) no previous sorafenib therapy for the liver tumour; (4) Child-Pugh A or B (≤ 7); (5) ECOG performance status of 0–2; and (6) neutrophil count > 1500/µl, PLT > 7.5 × 104 mm3, and Hb > 8.5 g/dl |

| Inclusion criteria for radiotherapy: (1) unresectable HCC with macroscopic hepatic vascular invasion; (2) Child-Pugh A or B; (3) ECOG performance status of 0–2; (4) no refractory ascites; and (5) no previous radiation therapy of the liver | |

| Sinclair (2014) | Inclusion criteria: PVT associated with unresectable HCC, who are not eligible for any curative procedure |

| Song (2014) | Eligibility criteria: (1) age 18–75 years; (2) radiologically confirmed PVTT in the main, first, or second branch of the portal vein; (3) ECOG performance status of 0 or 1; (4) Child-Pugh score B7; (5) WBC ≥ 3 × 109/l or absolute neutrophil count ≥ 1.0 × 109/l; and (6) PLT ≥ 50 × 109/l |

| Exclusion criteria: another primary tumour and other serious medical conditions, such as renal or cardiopulmonary insufficiency. Patients who were treated with sorafenib in the HAIC group and those who were treated with HAIC in the sorafenib group were also excluded | |

| Yang (2012) | Inclusion criteria: (1) advanced HCC without distant metastasis; (2) presence of PVT; (3) ECOG performance status of 0, 1, or 2; (4) Child-Pugh A or B; (5) life expectancy of at least 12 weeks; (6) total bilirubin concentration of ≤ 51.3 µmol/l; (7) HBV DNA positivity |

| Yoon (2013) | Inclusion criteria: (1) 18–80 years; (2) Child-Pugh class A or B (≤ 7); (3) HCC with major branch of portal vein invasion; (4) WBC ≥ 2,000/µl, absolute neutrophil count > 1,200/µl, Hb ≥ 8.0 g/dl, PLT > 50,000/µl, Cr < 1.7 mg/dl, TBIL ≤ 3.0 mg/dl, PT-INR ≤ 2.3 or PT ≤ 6 s; (5) ECOG performance status of 0–2 |

| Exclusion criteria: (1) Child-Pugh score ≥ 8; (2) age < 18 or ≥ 80 years; (3) ECOG performance status ≥ 3; (4) recipient of living donor or deceased donor liver transplantation |

ECOG – Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, HAIC – hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy, Hb – haemoglobin, HCC – hepatocellular carcinoma, PLT – platelets count, PVTT – portal vein tumour thrombus, TACE – transarterial chemoembolisation, TBIL – total bilirubin, WBC – white blood cell.

Sorafenib monotherapy versus other interventions

Sorafenib versus hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC)

Two retrospective studies compared the outcomes of sorafenib versus HAIC in HCC patients with PVTT [17, 18]. The first one was a single-centre study conducted in Japan with 40 cases [17]. In the HAIC group, 5-fluorouracil was employed as a chemotherapeutic agent, and pegylated interferon α2b was also subcutaneously administered. The investigators found that the objective early response rate was higher in the HAIC group than in the sorafenib group (71.4% vs. 10.5%, p < 0.01). More importantly, the survival rate was higher in the HAIC group than in the sorafenib group (6-month survival rate: 83.8% vs. 68.4%; 12-month survival rate: 77.8% vs. 37.7%; 18-month survival rate: 55.6% vs. 16.2%, p = 0.03). However, because the study was published in the abstract form, we could not evaluate the comparability of baseline characteristics between the two groups.

The second one was a multi-centre study conducted in South Korea with 110 cases [18]. In the HAIC group, the chemotherapeutic agents included cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil with or without epirubicin. The baseline Child-Pugh class and location of PVTT were comparable between the two groups, but the HAIC group enrolled a higher proportion of patients who underwent the combined loco-regional treatment than the sorafenib group. Compared with the sorafenib group, the HAIC group achieved more significant clinical efficacies, including a higher treatment response rate (complete response + partial response: 24% vs. 13.3%, p = 0.214), a higher disease control rate (90% vs. 45%, p < 0.001), a longer overall survival time (median: 7.1 months vs. 5.5 months, p = 0.011), and a longer time to progression (median: 3.3 months vs. 2.1 months, p = 0.034). However, the multivariate analysis did not identify HAIC as a significant prognostic factor. Therefore, well-designed RCTs are warranted to compare the advantages of HAIC with those of sorafenib in such patients.

Sorafenib versus transarterial chemoembolization (TACE)

High-level evidence from randomised controlled trials and meta-analysis has shown that TACE can significantly improve the survival of HCC patients [22]. According to the BCLC staging system, TACE is recommended as the first-line treatment option for the intermediate stage of HCC [3, 23]. Traditionally, the presence of PVTT is a relative contraindication for TACE, because the simultaneous blockage of hepatic artery and portal vein may lead to the liver failure. However, recent studies have confirmed the safety and feasibility of TACE in such patients [24]. At present, a phase II RCT conducted in South Korea is exploring the efficacy of sorafenib and TACE in advanced HCC patients with major branch of portal vein invasion (www.ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01480817) [21]. But this trial has two potential limitations, as follows: 1) the sample size needed is only 40; and 2) the primary endpoint is the time to progression, but not the overall survival.

Sorafenib alone versus radioembolisation

Transarterial radioembolisation with Yttrium-90 glass microspheres (TheraSphere® registry marker) is a promising treatment option for advanced HCC with PVTT [25–27]. A head-to-head multi-centre RCT is ongoing to compare the outcomes of sorafenib with those of radioembolisation in unresectable HCC patients with PVTT and Child-Pugh class A (www.ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01887717) [20, 28]. This study, which is sponsored by BTG International Inc., will recruit 328 cases in four Western countries (the USA, Italy, Spain, and the UK) during a period of about 4 years. In addition, an earlier French multi-centre RCT is comparing the outcomes between the HCC patients receiving sorafenib and radioembolisation (www.ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01482442) [29]. However, it should be noted that the HCC patients with and without PVTT will be considered as the target population.

Sorafenib alone versus radiotherapy

A Japanese retrospective study compared the outcomes of sorafenib with those of three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy in 97 HCC patients with PVTT [14]. In the entire cohort analysis, the overall survival time was comparable between patients receiving sorafenib and radiotherapy (median: 4.4 months vs. 5.9 months, p = 0.115). But the risk of bias was obvious. First, the enrolment periods were different. The patients in the sorafenib group were enrolled after 2009; by comparison, those in the radiotherapy group were enrolled after 2001. Considering that the management of advanced HCC has gradually improved over time, the selection of treatment modalities in the sorafenib group might be more appropriate. Second, the baseline characteristics were different. The sorafenib group had a significantly lower proportion of Child-Pugh class B (10% vs. 31%) and tumour thrombus within the main portal vein trunk (18% vs. 43%) than the radiation group. To minimise the selection bias, a propensity analysis was further performed in 56 HCC patients with PVTT and Child-Pugh class A. The overall survival time was significantly shorter in the sorafenib group than in the radiation therapy group (median: 4.8 months vs. 10.9 months, p = 0.002). This finding was also supported by the results of multivariate Cox regression analyses, which showed that radiation therapy should be identified as the independent predictor of survival (hazard ratio = 0.43, 95% confidence interval: 0.235–0.779, p = 0.007). These impressive findings indicated the superiority of radiation therapy over sorafenib in HCC patients with PVTT.

Sorafenib versus hepatic resection

A Korean retrospective study compared the results of sorafenib with hepatic resection in HCC patients with PVTT within the segmental branches and/or right and left portal vein [16]. In the total analysis of all cases enrolled between January 2000 and December 2011, the survival rate was higher in the hepatic resection group than in the sorafenib group (1-year rate: 63.6% vs. 32.3%; 2-year rate: 31.3% vs. 5.6%). Similarly, in the subgroup analysis of the cases who were enrolled in the era of sorafenib (since January 2008), the survival time remained longer in the hepatic resection group than in the sorafenib group (median: 24.6 months vs. 4.1 months). This finding suggested that hepatic resection should be superior to sorafenib in the improvement of survival in HCC patients with PVTT. However, their generalisation might be limited due to the absence of detailed information regarding baseline characteristics and retrospective nature.

Sorafenib alone versus sorafenib combined with other interventions

Sorafenib alone versus sorafenib + cryotherapy

Preliminary studies explored the efficacy and safety of cryoablation for the treatment of unresectable HCC [30–33]. Recently, a Chinese RCT has evaluated the clinical benefit of cryotherapy as an adjunctive treatment modality in HCC patients with PVTT receiving sorafenib [15]. Besides the response rate, the combination of sorafenib with cryotherapy provided a significantly longer overall survival time (median: 12.5 months vs. 8.6 months), a longer time to progression (median: 9.5 months vs. 5.3 months), a higher clinical efficacy rate (23% vs. 7.6%), and a higher disease control rate (65.4% vs. 44.2%). Multivariate Cox regression analysis also identified combined use of sorafenib and cryotherapy as the independent predictor of survival and time to progression. Thus, cryotherapy might be considered as an additional treatment option for HCC with PVTT, if sorafenib was employed.

Sorafenib alone versus sorafenib + percutaneous radiofrequency ablation (RFA)

An Italian RCT also explored whether or not the addition of RFA could improve the outcomes of sorafenib in HCC patients with PVTT and Child-Pugh class A [19]. The investigators reported a significantly higher survival rate in the combination group than in the sorafenib alone group (1-year rate: 60% vs. 37%; 2-year rate: 35% vs. 0%). On the basis of this finding, RFA should be an auxiliary choice of therapy in patients with HCC with PVTT receiving sorafenib.

Conclusions

Although sorafenib is regarded as the standard treatment option for advanced HCC, its clinical efficacy in HCC patients with PVTT has been frequently challenged by other interventions, such as HAIC, TACE, radioembolisation, radiotherapy, and hepatic resection. However, the relevant evidence is of relatively low quality. Thus, further RCTs with head-to-head comparisons of sorafenib with other interventions should be conducted. In addition, the evidence from RCTs suggested that cryoablation or radiofrequency ablation provide an additional survival benefit to HCC patients with PVTT receiving sorafenib.

Acknowledgments

Xingshun Qi and Xiaozhong Guo are joint senior authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tandon P, Garcia-Tsao G. Prognostic indicators in hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of 72 studies. Liver Int. 2009;29:502–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01957.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Association for the Study of the Liver. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novi M, Lauritano EC, Piscaglia AC, et al. Portal vein tumor thrombosis revascularization during sorafenib treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1852–4. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irtan S, Chopin-Laly X, Ronot M, et al. Complete regression of locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma induced by sorafenib allowing curative resection. Liver Int. 2011;31:740–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moroni M, Zanlorenzi L. Complete regression following sorafenib in unresectable, locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Future Oncol. 2013;9:1231–7. doi: 10.2217/fon.13.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kermiche-Rahali S, Di Fiore A, Drieux F, et al. Complete pathological regression of hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein thrombosis treated with sorafenib. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:171. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-11-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho JY, Paik YH, Lim HY, et al. Clinical parameters predictive of outcomes in sorafenib-treated patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2013;33:950–7. doi: 10.1111/liv.12168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou L, Li J, Ai DL, et al. Enhanced therapeutic efficacy of combined use of sorafenib and transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(Suppl):e1512. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyu068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marinelli S, Granito A, Terzi E, et al. Clinical predictors of response to sorafenib in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(Suppl):e15149. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho JY, Paik YH, Lim HY, et al. Analysis of clinical parameters as predictor of outcome in sorafenib-treated patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2012;56:462A. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakazawa T, Hidaka H, Shibuya A, et al. Overall survival in response to sorafenib versus radiotherapy in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma with major portal vein tumor thrombosis: propensity score analysis. BMC Gastroenterology. 2014;14:84. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-14-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Y, Lu Y, Wang C, et al. Cryotherapy is associated with improved clinical outcomes of sorafenib for the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Exp Therap Med. 2012;3:171–80. doi: 10.3892/etm.2011.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JM, Jang BK, Chung WJ, et al. The survival outcomes of hepatic resection compared with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus. Hepatol Int. 2014;8:S22–3. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasai K, Sawara K, Suzuki K. Combination therapy of intra-arterial 5-fluorouracil and systemic pegylated interferon alpha-2b for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(Suppl 4):A216. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song DS, Song MJ, Bae SH, et al. A comparative study between sorafenib and hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombosis. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:445–54. doi: 10.1007/s00535-014-0978-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giorgio A, Farella N, Di Sarno A, et al. Western trial comparing percutaneous radiofrequency of both hepatocellular carcinoma and the portal venous tumor thrombus plus sorafenib with sorafenib alone. J Hepatol. 2011;54:S542. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinclair P. A prospective randomized clinical trial on 90yttruim transarterial radioembolization (therasphere(registered trademark)) vs standard of care (sorafenib) for the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein thrombosis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25:817.e20. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lauro RM, Reggiani P, Caccamo L, et al. Laparoscopic thermal-ablation of HCC with microwave: preliminary experience and results. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23:853.e27–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Llovet JM, Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology. 2003;37:429–42. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005;42:1208–36. doi: 10.1002/hep.20933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung GE, Lee JH, Kim HY, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization can be safely performed in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma invading the main portal vein and may improve the overall survival. Radiology. 2011;258:627–34. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10101058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sangro B, Inarrairaegui M, Bilbao JI. Radioembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:464–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazzaferro V, Sposito C, Bhoori S, et al. Yttrium-90 radioembolization for intermediate-advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase 2 study. Hepatology. 2013;57:1826–37. doi: 10.1002/hep.26014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salem R, Mazzaferro V, Sangro B. Yttrium 90 radioembolization for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: biological lessons, current challenges, and clinical perspectives. Hepatology. 2013;58:2188–97. doi: 10.1002/hep.26382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LaPointe Rudow D, Brown RS, Jr, Emond JC, et al. One-year morbidity after donor right hepatectomy. Liver Transplantation. 2004;10:1428–31. doi: 10.1002/lt.20280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lauro RM, Maggi U, Paone G, et al. Contrast enhanced ultrasound (CEUS): a new low-cost imaging procedure for hepatic artery and portal vein early complications after liver transplantation. Liver Transplantation. 2009;15:S223. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang Y, Wang C, Lu Y, et al. Outcomes of ultrasound-guided percutaneous argon-helium cryoablation of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:674–84. doi: 10.1007/s00534-011-0490-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu B, Xiao YY, Zhang X, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-guided percutaneous cryoablation of hepatocellular carcinoma in special regions. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2010;9:384–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimizu T, Sakuhara Y, Abo D, et al. Outcome of MR-guided percutaneous cryoablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:816–23. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orlacchio A, Bazzocchi G, Pastorelli D, et al. Percutaneous cryoablation of small hepatocellular carcinoma with US guidance and CT monitoring: initial experience. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008;31:587–94. doi: 10.1007/s00270-008-9293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]