Abstract

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are among the most frequent causes of idiosyncratic, drug-induced liver injury (IDILI). Mechanisms of IDILI are unknown, but immune responses are suspected to underlie them. In animal models of IDILI, the cytokines tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) and interferon-gamma (IFNγ) are essential to the pathogenesis. Some drugs associated with IDILI interact with cytokines to kill hepatocytes in vitro, and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) might play a role. We tested the hypothesis that caspases and MAPKs are involved in NSAID/cytokine-induced cytotoxicity. NSAIDs that are acetic acid (AA) derivatives and associated with IDILI synergized with TNFα in causing cytotoxicity in HepG2 cells, and IFNγ enhanced this interaction. NSAIDs that are propionic acid (PA) derivatives and cause IDILI that is of less clinical concern also synergized with TNFα, but IFNγ was without effect. Caspase inhibition prevented cytotoxicity from AA and PA derivative/cytokine treatment. Treatment with a representative AA or PA derivative induced activation of the MAPKs c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and p38. Inhibition of either JNK or ERK reduced cytotoxicity from cytokine interactions with AA derivatives. In contrast, an ERK inhibitor potentiated cytotoxicity from cytokine interactions with PA derivatives. An AA derivative but not a PA derivative enhanced IFNγ-mediated activation of STAT-1, and this enhancement was ERK-dependent. These findings raise the possibility that some IDILI reactions result from drug/cytokine synergy involving caspases and MAPKs and suggest that, even for drugs within the same pharmacologic class, synergy with cytokines occurs by different kinase signaling mechanisms.

Keywords: NSAID, cytokine, idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury, JNK, ERK

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is the leading cause of acute liver failure in the USA and remains the most common adverse effect associated with failure to obtain U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for new drugs (Aithal et al., 2011). Idiosyncratic DILI (IDILI), a subset of DILI, occurs in a small fraction of patients taking a drug and can result in severe liver injury or death. These reactions have resulted in removal of many drugs from the market that are efficacious and safe in the majority of patients.

Mechanisms underlying IDILI remain unproven, and the reactions are not predicted by typical preclinical toxicity testing. The infrequency of most IDILI responses suggests that individual susceptibility as well as characteristics of the offending drug are needed to elicit a response. A longstanding hypothesis is that IDILI-associated drugs activate a damaging adaptive immune response (Uetrecht, 1999). Specific human leukocyte antigen polymorphisms are associated with liver injury induced by some drugs, suggesting an important role for adaptive immune responses in the pathogenesis of IDILI (Tujios and Fontana, 2011). Another hypothesis suggests that activation of the innate immune system during drug therapy can render an individual susceptible to injury from an otherwise nontoxic dose of the drug (Roth and Ganey, 2011). Importantly, inflammatory cytokines are expressed and mediate critical events in both adaptive and innate immune responses. Indeed, in several rodent models of IDILI based on interaction of drugs with an immune response, the cytokines tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) and interferon-gamma (IFNγ) proved to be critical to the pathogenesis of hepatocellular injury (Dugan et al., 2011; Shaw et al., 2009a, b; Zou et al., 2009).

Recently published studies suggest that toxic cytokine/drug synergy can be recapitulated in vitro. For example, some drugs associated with IDILI synergize with TNFα to kill hepatocytes in vitro, and a role for aberrant mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling has been implicated in this response (Beggs et al., 2014; Cosgrove et al., 2009, 2010; Fredriksson et al., 2011). TNFα is known to activate the MAPKs c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 transiently (Wullaert et al., 2007). MAPKs are commonly activated in response to cellular stress, and if their activation is prolonged cell death can ensue (Anderson, 1997). IFNγ activates the Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) pathway, which can also mediate cell death (Stephanou and Latchman, 2003). Exactly how drugs associated with IDILI synergize with cytokines to cause hepatocellular damage remains incompletely understood, although it is likely that activation of caspases and MAPKs plays a role (Beggs et al., 2014; Fredriksson et al., 2011).

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and antibiotics are the most frequent causes of IDILI. The observation that rheumatoid arthritis increases the risk of NSAID-induced liver injury more than 10-fold in human patients suggests that immune mediators contribute to IDILI pathogenesis from drugs in this pharmacologic class (Garcia Rodriguez et al., 1994). This suggestion is supported by results in animal models. In one such model, rodents treated with diclofenac (DCLF) in combination with lipopolysaccharide (LPS), an activator of the innate immune system, developed hepatocellular injury which did not occur after treatment with either DCLF or LPS alone (Deng et al., 2006). In addition, DCLF potentiated LPS-mediated expression of TNFα and IFNγ genes in rats (Ramm and Mally, 2013). Similarly, sulindac (SLD), another NSAID associated with IDILI, produced TNFα-dependent liver injury in rats cotreated with LPS (Zou et al., 2009).

Nearly all NSAIDs have been implicated in causing IDILI; however, the severity and lesion morphology of NSAID-induced hepatotoxicity varies substantially, likely due at least in part to the diversity of chemical structures within this drug class (O’Connor et al., 2003; Teoh and Farrell., 2003). In this study, we tested the hypothesis that NSAIDs with idiosyncrasy liability synergize with TNFα and IFNγ to cause hepatocellular toxicity in vitro. To gain insight into the mechanism of the NSAID/cytokine-induced cytotoxic interaction, the involvement of caspases and MAPKs was examined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

NSAIDs and MAPK inhibitors were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri). Z-VAD-FMK and recombinant human TNFα and IFNγ were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, Minnesota). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles Medium (DMEM), Williams’ Medium E, l-glutamine, fetal bovine serum (FBS), Antibiotic-Antimycotic (ABAM), and 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA were purchased from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, California). All antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, Massachusetts).

Animals

Male C57Bl/6 J mice purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine) were allowed to acclimate for at least 1 week upon arrival. They were housed in a 12-hour light/dark cycle, were fed a standard chow (8640 Teklad 22/5 Rodent Diet, Harlan Laboratories, Madison, WI, USA), and had continual access to bottled spring water. All procedures were conducted with the approval of the Michigan State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cell culture

Human hepatoma HepG2 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Virginia) were chosen because they are insensitive to the harmful effects of cytokines yet express both TNFα and IFNγ receptors (Hershey and Schreiber, 1989; Stonāns et al., 1999). Moreover, HepG2 cells respond similarly to primary mouse hepatocytes and primary human hepatocytes with regard to the cytotoxic interaction between IDILI-associated drugs and cytokines (Beggs et al., 2014; Cosgrove et al., 2009). It is known that HepG2 cells have low expression of phase 1 drug metabolizing enzymes compared with primary human hepatocytes. However, compared with primary human hepatocytes, they have similar expression of phase 2 drug metabolizing enzymes (Westerink and Schoonen, 2007a, b). The only NSAID used in this study for which it is suspected that phase 1 metabolism is required for liver injury is SLD. In this study, the active metabolite of SLD, SLD sulfide, was used. We previously demonstrated that SLD sulfide, but not the parent compound, synergized with cytokines to cause cytotoxicity in HepG2 cells and primary rat hepatocytes (Zou et al., 2009). With regard to the remaining NSAIDs used in this study, there is not convincing evidence that bioactivation is required for liver injury in humans. Cells were grown in 25-cm2 tissue culture-treated flasks and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% ABAM. They were cultured at 37°C in 95% air and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. They were passaged when they reached ∼80% confluence.

Primary murine hepatocytes were isolated as described previously by Klaunig et al. (1981). Hepatocytes were isolated using a 2-step collagenase perfusion method. Viability of isolated hepatocytes was assessed by trypan blue exclusion. Only cells with >85% viability were used for experiments. Hepatocytes were plated with Williams’ Medium E supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% ABAM, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 100 nM insulin. After plating, they were cultured at 37°C in 95% air and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator and allowed 3 h to attach prior to treatment.

IDILI classification

NSAIDs were classified according to their ability to cause IDILI (Table 1). The criteria used to classify the drugs in this study was established by Xu et al. (2008) and takes into consideration postmarketing label information as well as numbers of published clinical case reports.

Table 1.

NSAID Subclass and Maximal Plasma Concentration (Cmax) From Therapeutic Doses in Human Patients

| NSAID | Structural Sub-class | IDILI Potential | Cmax (μg/ml) | Molecular Weight (g/mol) | Cmax Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCLF | AA derivative | Yes | 2.4 | 296.15 | Xu et al. (2008) |

| SLD sulfide | AA derivative | Yes | 1.6 | 340.41 | Reid et al. (2008) |

| BRM | AA derivative | Yes | 4.8 | 356.15 | Gumbhir-Shah et al. (1997) |

| IBU | PA derivative | Yes | 32.9 | 206.29 | Bramlage and Goldis (2008) |

| NAP | PA derivative | Yes | 75.9 | 252.23 | Setiawati et al. (2009) |

| Aspirin | Salicylic acid derivative | No | 7.6 | 180.16 | Brandon et al. (1986) |

Cytotoxicity assessment

HepG2 cells were plated at a density of 4 × 104 cells per well in black-walled, 96-well tissue culture plates and were allowed to attach overnight before treatment with compounds. DCLF, bromfenac (BRM), ibuprofen (IBU), and naproxen (NAP) were reconstituted in sterile water. SLD sulfide and aspirin were reconstituted in DMSO. Cells were treated with various concentrations of each NSAID or its vehicle, and simultaneously with TNFα (10 ng/ml) and/or IFNγ (10 ng/ml) or their vehicles (PBS). Cells were treated with NSAID concentrations ranging from 0 to 100 times the maximal plasma concentration (Cmax) observed in human patients. The Cmax value for each NSAID is presented in Table 1. One hundred times the Cmax was considered a pharmacologically relevant dosing limit for this in vitro study based on scaling factors described in Xu et al. (2008). Preliminary concentration-response studies were conducted with each cytokine to find a concentration that produced a robust cytotoxic interaction in the presence of DCLF (Supplementary Figs. 1A and 1B). The cytokine concentrations chosen for this study are within 10-fold of the concentrations found in serum of human patients undergoing an inflammatory response (Pinsky et al., 1993; Taudorf et al., 2007). Cells were exposed to drug/cytokine combinations for 24 h, and cytotoxicity was evaluated by measuring lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release from the cells into culture medium using the Homogeneous Membrane Integrity Assay kit from Promega (Madison, Wisconsin). For drugs that interfered with the fluorescence-based assay (IBU and NAP), a spectrophotometric method was used to measure LDH release (Vanderlinde, 1985).

To investigate the roles of caspases and the MAPKs, pharmacological inhibitors of these pathways were used (40 µM Z-VAD-FMK for caspases, 20 µM SP600125 for JNK, 20 µM U0126 for extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and 20 μM SB203580 for p38). Inhibitors were reconstituted in DMSO, resulting in a maximal final concentration of 0.4% DMSO in experiments involving SLD sulfide/Z-VAD-FMK or 0.2% DMSO in all other experiments. In brief, cells were treated with an inhibitor alone or simultaneously in combination with TNFα and/or IFNγ and with one concentration of NSAID that produced strong cytotoxic synergy in the presence of cytokines. LDH release was measured 24 h after treatment.

Primary mouse hepatocytes were plated at a density of 1.25 × 105 cells per well in collagen-coated 24-well tissue culture-treated plates. Cells were allowed 3 h to attach followed by 2 washes with warm PBS then were treated with BRM alone or in combination with TNFα and/or IFNγ prepared in serum-free Williams’ Medium E supplemented with 1% ABAM and 2 mM l-glutamine. After 24 h of exposure to drugs and/or cytokines, cell supernatant was collected, and attached cells were lysed with 1% triton-X. The supernatant and lysate were transferred to 96-well plates and analyzed for alanine aminotransferase activity as described by Luyendyk et al. (2005).

Caspase-3 activity

Caspase-3 activity was measured using the Caspase-3 Fluorometric Assay Kit purchased from R&D Systems. HepG2 cells were plated at 1.2 × 106 cells per well in 6-well tissue culture plates. Cells were treated with a NSAID alone or in combination with TNFα and/or IFNγ. Cells were lysed and centrifuged after 24 h of exposure. 50 μl of lysate were added to black-walled, 96-well plates and incubated with assay reaction buffer and fluorogenic substrate for 1 h. The plate was then read on a fluorescent plate reader at an excitation wavelength of 400 nm and an emission wavelength of 505 nm.

Protein isolation

Cells (1.2 × 106 per well) were plated in 6-well tissue culture plates and allowed to adhere overnight. They were exposed to one concentration of NSAID and its vehicle alone or in combination with TNFα and/or IFNγ for 12 or 18 h. Cells were rinsed with cold PBS followed by an addition of 150 µl of radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing HALT protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, Illinois). Cells were scraped, collected, placed in microcentrifuge tubes, and incubated on ice for 10 min. During the 10-min incubation, the tubes were vortexed intermittently. Lysates were centrifuged for 25 min at 20 000× g. The supernatants containing whole cell extracts were collected, placed in fresh, chilled tubes, and stored at −80°C until use. Protein concentrations were quantified using the bicinchoninic acid assay (Thermo Scientific).

Western analysis

For detection of MAPKs and phosphorylated STAT-1 (pSTAT-1) in whole cell lysates, protein (30 µg for JNK and 15 µg for ERK, p38 and STAT-1) was loaded onto precast NuPAGE 12% Bis–Tris gels (Life Technologies) and subjected to electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts). Membranes were blocked for 1 h with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) reconstituted in 1% tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% tween-20 (TBSt) for detection of JNK, p38 and STAT-1 or blocked with TBS-based LI-COR blocking buffer (Lincoln, Nebraska) for detection of ERK. Membranes were probed with antibodies directed against phosphorylated JNK (pJNK), total JNK, phosphorylated ERK (pERK), total ERK, phosphorylated p38 (pp38), pSTAT-1 (Tyrosine 701), pSTAT-1 (Serine 727), and α-Tubulin. Primary antibodies were diluted in appropriate buffers to 1:1000. Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, after which they were washed with TBSt followed by an addition of secondary antibodies. Goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody was diluted in 5% BSA in TBSt at a concentration of 1:2500 for pJNK, 1:5000 for total JNK, 1:5000 for pp38, 1:5000 for total p38, 1:5000 for pSTAT-1 (Tyrosine 701), 1:5000 for pSTAT-1 (Serine 727), and 1:5000 for α-Tubulin. Clarity Western ECL substrate (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California) was used to visualize HRP and the substrate was developed on HyBlot CL film (Denville Scientific, Metuchen, New Jersey). For the detection of ERK, donkey anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit infrared (IR) dye-conjugated secondary antibodies were diluted in LI-COR blocking buffer to 1:3000, and IR fluorescence was detected using the LI-COR Odyssey IR Imaging System. All images were quantified by performing densitometry using image J software.

Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Data were subjected to log transformation as necessary to achieve normality and equal variance. Data were analyzed via a 1-way or 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Tukey’s post-hoc test was used to perform multiple, pairwise comparisons between treatment groups. The criterion for significance was set at α = 0.05.

RESULTS

NSAID/Cytokine-Induced Cytotoxicity: Concentration–Response

The NSAIDs chosen for this study are DCLF, BRM, SLD sulfide (the active metabolite of SLD), NAP, IBU, and aspirin. Aspirin is the only one of these drugs that has not been associated with IDILI. Within the NSAID class of pharmaceuticals, there are a variety of subclasses based on chemical structure. There are 3 NSAID subclasses represented among the drugs used in our study. DCLF, BRM, and SLD sulfide are acetic acid (AA) derivatives, IBU and NAP are propionic acid (PA) derivatives, and aspirin is a salicylic acid derivative. It is worth noting that AA derivatives and PA derivatives are among the most hepatotoxic NSAIDs (Teoh and Farrell, 2003). Moreover, among the IDILI-associated drugs used in this study, the AA derivatives are of greater clinical concern than the PA derivatives (Unzueta and Vargas 2013).

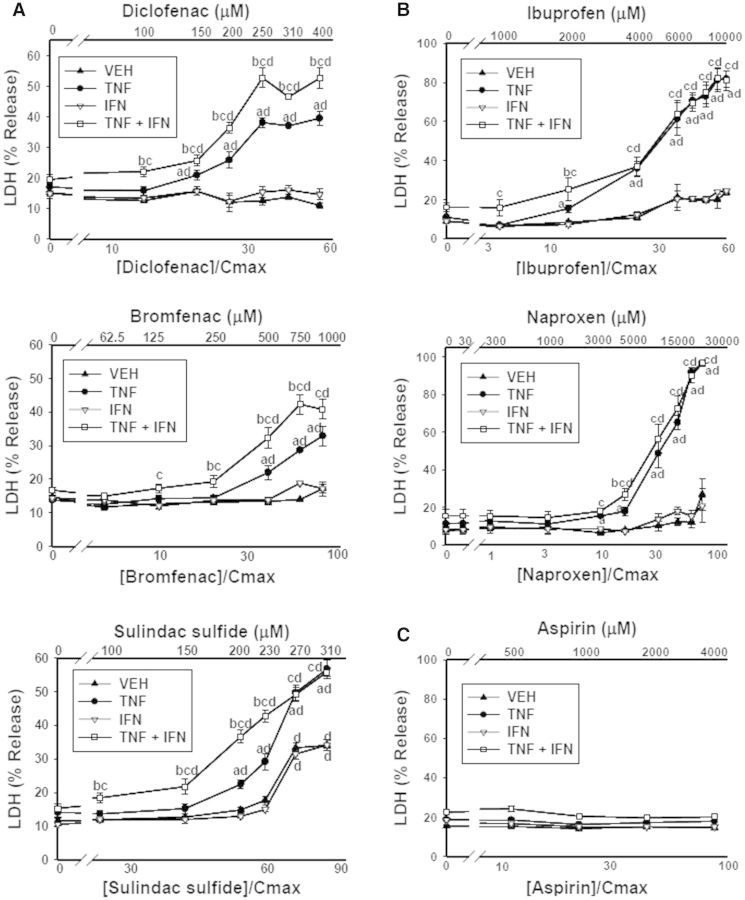

As expected, treatment of cells with TNFα and/or IFNγ in the absence of drug did not result in release of LDH (Fig. 1). With the exception of SLD sulfide, treatment with NSAID alone did not result in cytotoxicity. All 5 IDILI-associated NSAIDs synergized with TNFα in a concentration-dependent manner to cause cytotoxicity (Figs. 1A and 1B). IFNγ by itself did not influence drug-induced cytotoxicity; however, in the presence of TNFα it enhanced the cytotoxicity mediated by DCLF, BRM, and SLD sulfide (Fig. 1A) but had no effect on the toxicity of IBU and NAP (Fig. 1B). Aspirin did not synergize with TNFα or IFNγ alone or in combination to kill HepG2 cells (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

Interaction of NSAIDs with cytokines leads to synergistic cytotoxicity. HepG2 cells were treated with NSAIDs that have (A, B) or do not have (C) IDILI liability alone or in combination with TNFα (10 ng/ml) and/or IFNγ (10 ng/ml). The NSAIDs that have IDILI liability are grouped according to structural subclass: (A) AA derivatives; (B) PA derivatives; (C) salicylic acid derivative. a, significantly different from VEH (no cytokine) within an NSAID concentration; b, significantly different from TNFα within an NSAID concentration; c, significantly different from IFNγ within an NSAID concentration; d, significantly different from 0 μM NSAID within a cytokine group. Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M of at least 5 separate experiments. VEH, vehicle; TNF, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; IFN, interferon-gamma; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

Some of the NSAIDs used in this study, in addition to dozens of other IDILI-associated drugs, synergize with cytokines to cause death of primary human hepatocytes (Cosgrove et al., 2009). Drug/cytokine-induced cytotoxic synergy observed in primary human hepatocytes was recapitulated in HepG2 cells in spite of the low phase 1 metabolism observed in this cell line (Cosgrove et al., 2009). The cytotoxic interaction observed here in HepG2 cells between BRM and TNFα, as well as the IFNγ-mediated enhancement of BRM/TNFα-induced cytotoxicity (Fig. 1A), was observed in primary mouse hepatocytes as well (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Cytotoxic Synergy Between Cytokines and NSAIDs Requires Caspases

Fredriksson et al. (2011) reported that DCLF/TNFα-mediated cytotoxicity in HepG2 cells depends on caspases. In addition, Zou et al. (2009) demonstrated that SLD sulfide synergizes with TNFα to cause caspase activation that led to cell death. We tested the hypothesis that this holds true for other NSAIDs and for the IFNγ-mediated enhancement of NSAID/TNFα-induced cytotoxicity.

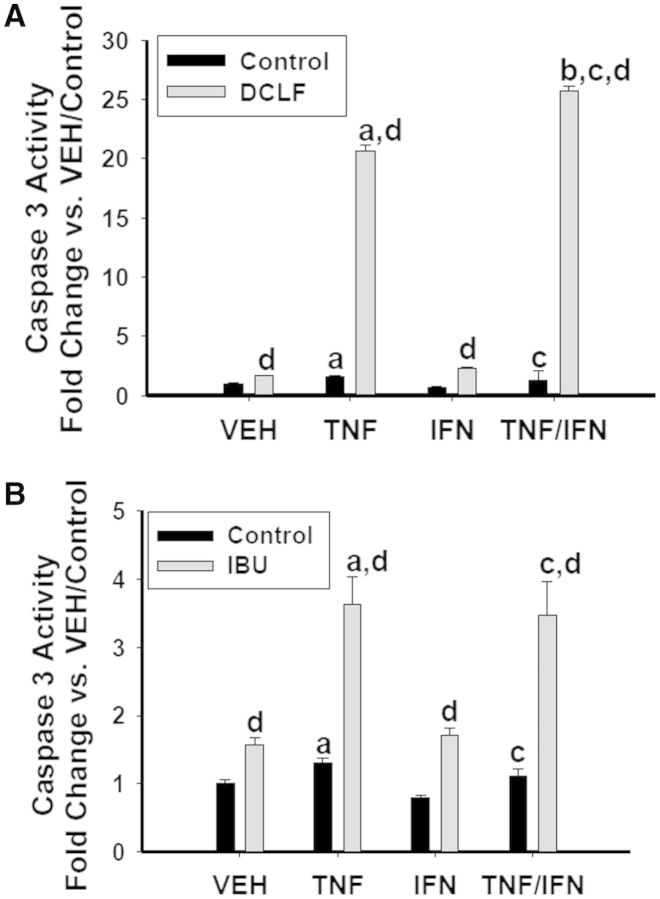

Of the 3 NSAID subclasses used in this study, 2 of them (the AA derivatives and PA derivatives) interacted with cytokines to kill cells. Although these 2 subclasses differed in the manner in which they synergized with the cytokines, within subclass they responded similarly to each other. Consequently, we selected a representative AA derivative (DCLF) and PA derivative (IBU) to evaluate caspase involvement in the NSAID/cytokine-induced cytotoxic interaction. For this experiment and all subsequent ones, we selected an NSAID concentration that resulted in strong cytotoxic synergy with TNFα and/or IFNγ. Both DCLF and IBU induced caspase 3 activation within 24 h of treatment (Fig. 2). Addition of TNFα potentiated caspase 3 activation by the drugs. Consistent with the cytotoxicity data presented in Figure 1, IFNγ enhanced caspase 3 activation induced by DCLF/TNFα but not by IBU/TNFα (Fig. 2). Treatment with the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK completely protected cells from NSAID/TNFα-induced cytotoxicity (Fig. 3). In addition, the IFNγ-mediated enhancement of cytotoxicity in cells treated with AA derivatives/TNFα was eliminated by Z-VAD-FMK treatment.

FIG. 2.

Caspase activation in response to DCLF/cytokine and IBU/cytokine treatment. HepG2 cells were treated with (A) a representative AA derivative (DCLF: 250 μM) or (B) a representative PA derivative (IBU: 6 mM) alone or in combination with TNFα and/or IFNγ, and cell lysates were collected 24 h after treatment for measurement of caspase 3 activity. a, significantly different from VEH; b, significantly different from TNFα; c, significantly different from IFNγ; d, significantly different from control. Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M of at least 3 separate experiments.VEH, vehicle; TNF, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; IFN, interferon-gamma; DCLF, diclofenac; IBU, ibuprofen.

FIG. 3.

Caspases are involved in the NSAID/cytokine-induced cytotoxic interaction. HepG2 cells were treated with (A) AA derivatives (DCLF: 250 µM, BRM: 750 µM or SLD sulfide: 200 μM), or (B) PA derivatives (IBU: 6 mM or NAP: 10 mM) alone or in combination with TNFα and/or IFNγ. Cells were also incubated in the presence and absence of the pan-caspase inhibitor ZVAD-FMK (40 μM). Cytotoxicity was measured 24 h later. a, significantly different from VEH within NSAID/inhibitor treatment; b, significantly different from TNFα within NSAID/inhibitor treatment; c, significantly different from Control within a cytokine group; d, significantly different from NSAID without inhibitor within a cytokine group. Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M of at least 5 separate experiments. VEH, vehicle; TNF, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; IFN, interferon-gamma; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; DCLF, diclofenac; BRM, bromfenac; SLD, sulindac; IBU, ibuprofen; NAP, naproxen.

Cytotoxic Synergy Between Cytokines and NSAIDs Involves Activation of JNK

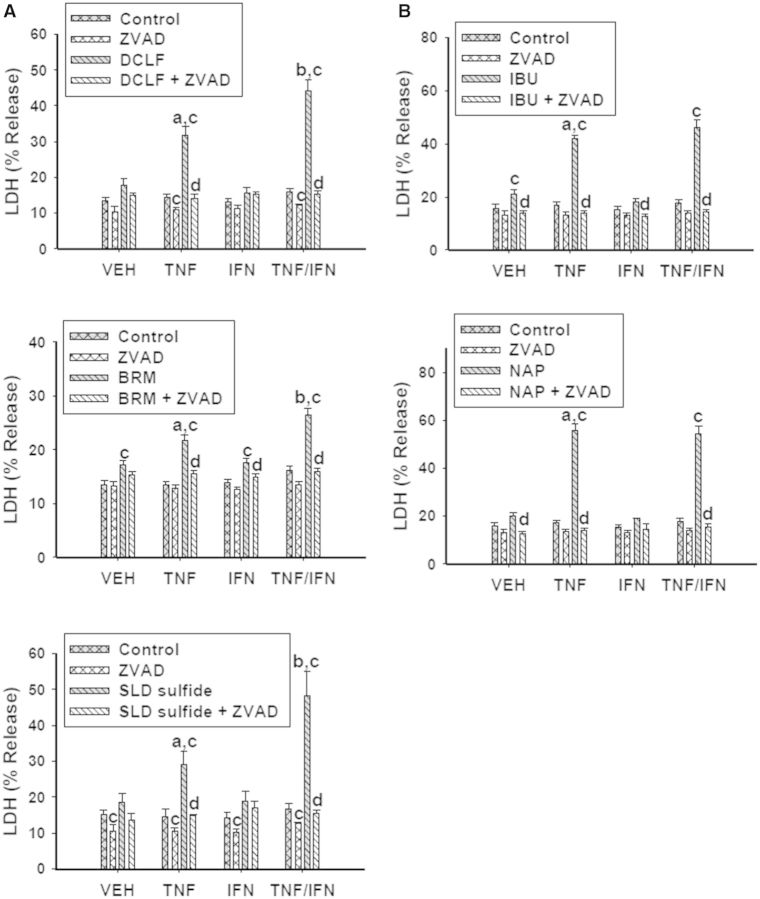

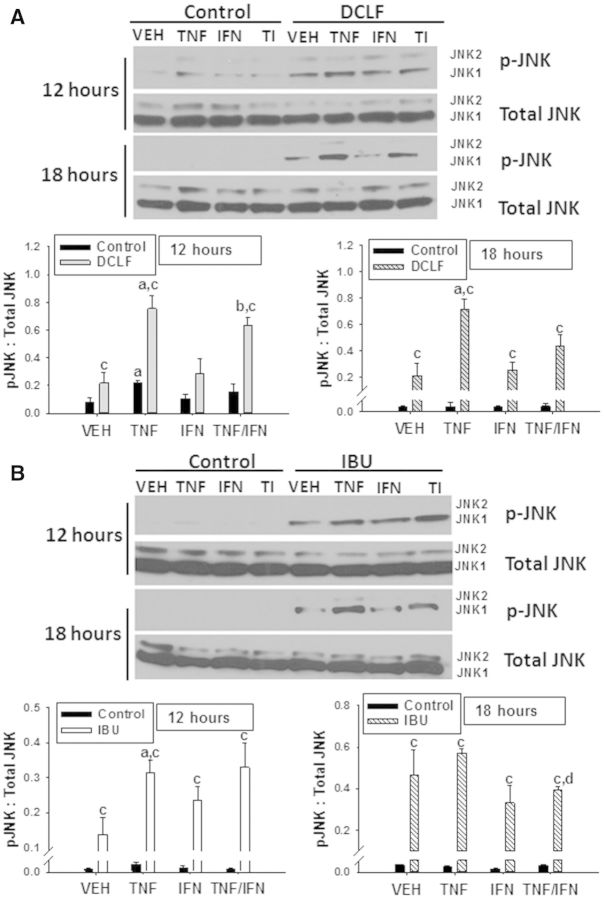

As described earlier, a representative AA derivative (DCLF) and PA derivative (IBU) were selected to examine the expression of phosphorylated (activated) JNK (pJNK). Based on the time-course of cytotoxicity after treatment with DCLF and cytokines (Supplementary Fig. 3), 2 times were selected: a time at which there was no cytotoxicity (12 h) and a time at which cytotoxicity was observed (18 h). Treatment with TNFα in the absence of drug (Control) caused expression of pJNK at 12 h (Fig. 4A). In the absence of drug, expression of pJNK was unchanged by treatment with TNFα, IFNγ, or TNFα/IFNγ at 18 h (Figs. 4A and 4B). At 12 h, treatment with DCLF caused phosphorylation of JNK which was enhanced in the presence of TNFα. Treatment with IFNγ did not alter DCLF/TNFα-induced JNK phosphorylation. By 18 h, DCLF caused JNK activation in the absence of TNFα. TNFα increased this response, but IFNγ did not alter JNK activation either alone or in the presence of DCLF/TNFα. In contrast, IBU significantly activated JNK by itself at both 12 and 18 h (Fig. 4B). IBU-mediated JNK activation was enhanced in the presence of TNFα at 12 h, whereas IFNγ was without effect.

FIG. 4.

HepG2 cells were treated with (A) a representative AA derivative (DCLF: 250 µM) or (B) a representative PA derivative (IBU: 6 mM) alone or in combination with TNFα and/or IFNγ, and protein extracts were collected 12 or 18 hours after treatment. p-JNK and total JNK protein were detected via western analysis. Representive blots are shown. Densitometry was performed using image J software. a, significantly different from VEH within an NSAID treatment. b, significantly different from IFNγ within an NSAID treatment. c, significantly different from Control within a cytokine treatment. d, significantly different from TNFα within an NSAID treatment. Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M of 3 separate experiments. Abbreviations: VEH, vehicle; TNF, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; IFN, interferon gamma; TI, tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma; DCLF, diclofenac; IBU, ibuprofen.

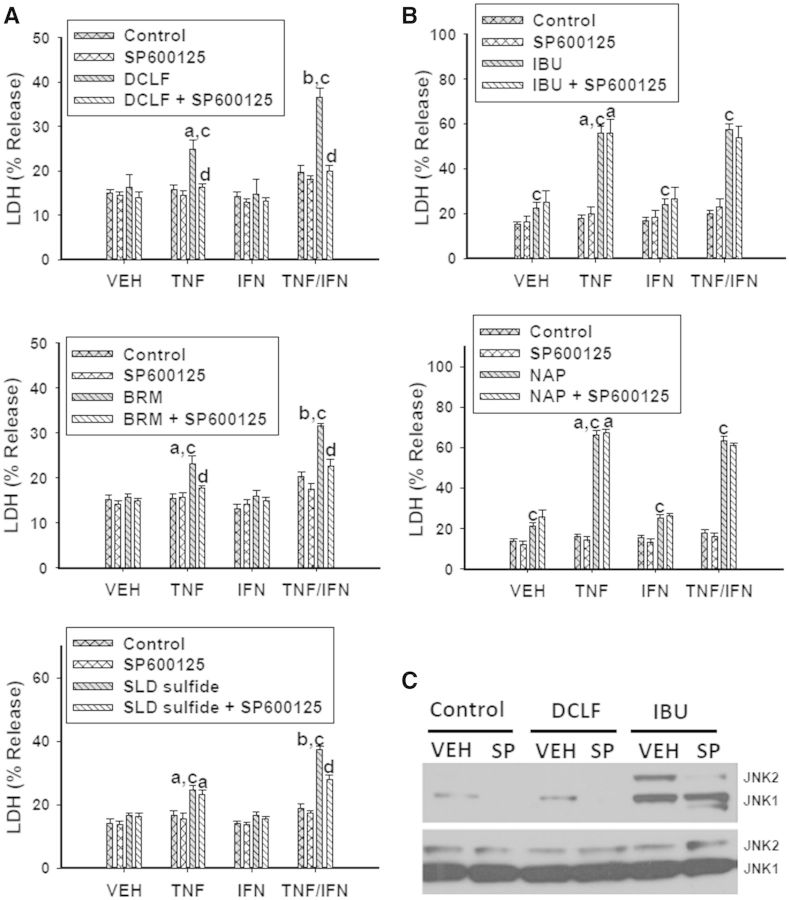

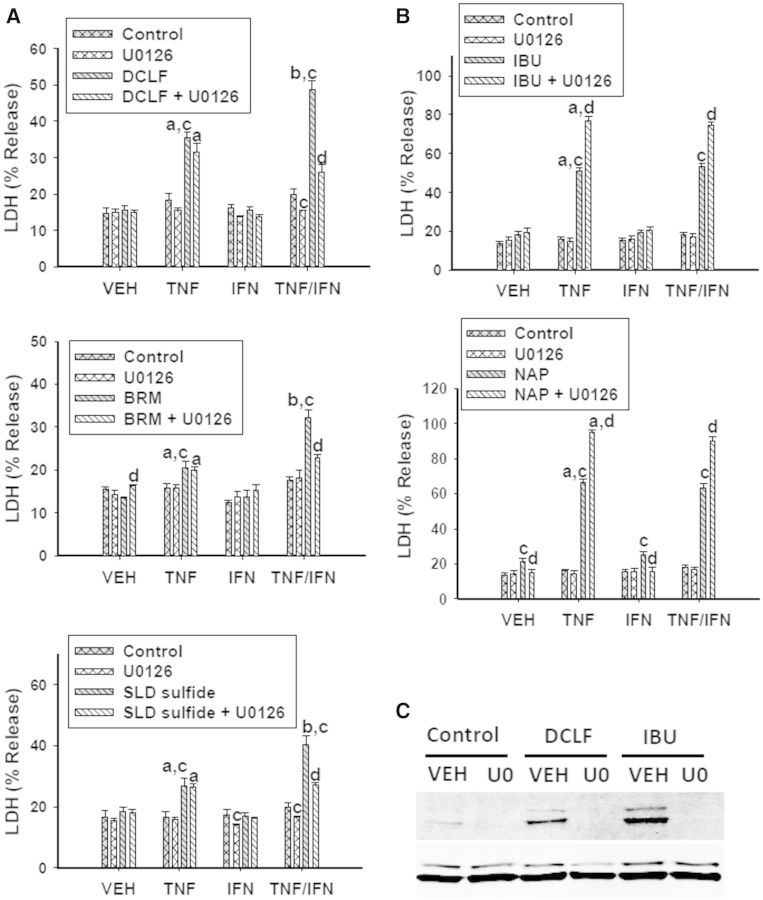

We next examined the involvement of JNK in NSAID/cytokine-induced cytotoxicity. Treatment with SP600125, an inhibitor of JNK activation, significantly reduced cytotoxicity mediated by cytokines in combination with NSAIDs containing an AA moiety (Fig. 5A). In contrast, SP600125 treatment did not alter the cytotoxic interaction for NSAIDs containing a PA moiety (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, treatment with SP600125 eliminated VEH- and DCLF-induced JNK activation but was ineffective at eliminating IBU-mediated JNK activation (Fig. 5C, Supplementary Fig. 4A).

FIG. 5.

JNK is involved in the NSAID/cytokine-induced cytotoxic interaction. HepG2 cells were treated with (A) AA derivatives (DCLF: 250 µM, BRM: 750 µM or SLD sulfide: 200 μM), or (B) PA derivatives (IBU: 6 mM or NAP: 10 mM) alone or in combination with TNFα and/or IFNγ. Cells were also incubated in the presence and absence of the JNK inhibitor SP600125 (20 µM). Cytotoxicity was measured 24 h later. (C) Cells were treated with a representative AA derivative (DCLF: 250 µM) or a representative PA derivative (IBU: 6 mM) in the presence or absence of SP600125 for 12 h, and p-JNK and total JNK protein were detected via western analysis. a, significantly different from VEH within NSAID/inhibitor treatment; b, significantly different from TNFα within NSAID/inhibitor treatment; c, significantly different from Control within a cytokine group; d, significantly different from NSAID without inhibitor within a cytokine group. Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M of at least 5 separate experiments. VEH, vehicle; TNF, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; IFN, interferon-gamma; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; DCLF, diclofenac; BRM, bromfenac; SLD, sulindac; IBU, ibuprofen; NAP, naproxen; SP, SP600125.

Cytotoxic Synergy Between Cytokines and NSAIDs Involves Activation of ERK

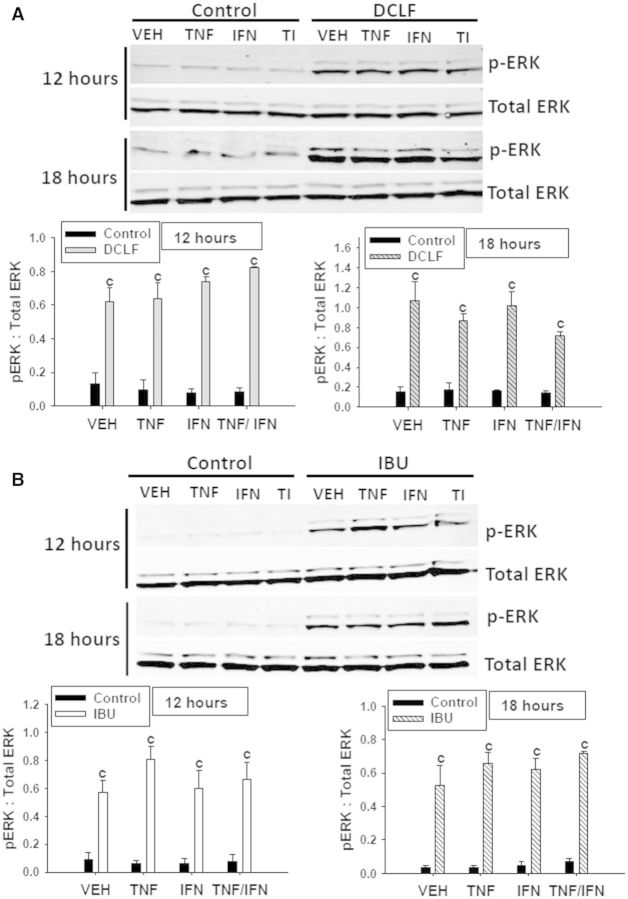

Treatment with cytokines in the absence of drug (Control) did not result in ERK activation (Fig. 6). Treatment with DCLF caused activation of ERK at 12 h that was still evident at 18 h (Fig. 6A). Neither TNFα nor IFNγ alone or in combination affected DCLF-mediated activation of ERK. Similarly, treatment with IBU caused persistent ERK activation that was unaltered by the presence of cytokines (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

DCLF and IBU treatment induce prolonged activation of ERK. HepG2 cells were treated with (A) a representative AA derivative (DCLF: 250 μM) or (B) a representative PA derivative (IBU: 6 mM) alone or in combination with TNFα and/or IFNγ, and protein extracts were collected 12 or 18 h after treatment. p-ERK and total ERK protein were detected via western analysis. Representative blots are shown. Densitometry was performed using image J software. c, significantly different from Control within a cytokine treatment. Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M of 3 separate experiments. VEH, vehicle; TNF, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, IFN, interferon-gamma; TI, tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma; DCLF, diclofenac; IBU, ibuprofen.

U0126 prevents ERK phosphorylation by inhibiting the MAPK kinase (MEK) that directly phosphorylates ERK. Treatment with U0126 did not affect cytotoxicity mediated by AA derivatives in combination with TNFα; however, it significantly reduced the IFNγ-mediated enhancement of AA derivative/TNFα-mediated cytotoxicity (Fig. 7A). In contrast, treatment with U0126 potentiated cytotoxicity caused by PA derivatives in combination with cytokines (Fig. 7B). The MEK inhibitor U0126 was effective at eliminating ERK activation induced by DCLF and IBU (Fig. 7C, Supplementary Fig. 4B).

FIG. 7.

ERK is involved in the NSAID/cytokine-induced cytotoxic interaction. HepG2 cells were treated with (A) AA derivatives (DCLF: 250 µM, BRM: 750 µM or SLD sulfide: 200 μM), or (B) PA derivatives (IBU: 6 mM or NAP: 10 mM) alone or in combination with TNFα and/or IFNγ. NSAID/cytokine combinations were also incubated in the presence and absence of the ERK inhibitor U0126 (20 μM). Cytotoxicity was measured 24 h later. (C) Cells were treated with a representative AA derivative (DCLF: 250 µM) or a representative PA derivative (IBU: 6 mM) in the presence or absence of U0126 for 12 h and p-ERK and total ERK protein was detected via western analysis. a, significantly different from VEH within NSAID/inhibitor treatment; b, significantly different from TNFα within NSAID/inhibitor treatment; c, significantly different from Control within a cytokine group; d, significantly different from NSAID without inhibitor within a cytokine group. Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M of at least 5 separate experiments. VEH, vehicle; TNF, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; IFN, interferon-gamma; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; DCLF, diclofenac; BRM, bromfenac; SLD, sulindac; IBU, ibuprofen; NAP, naproxen; U0, U0126.

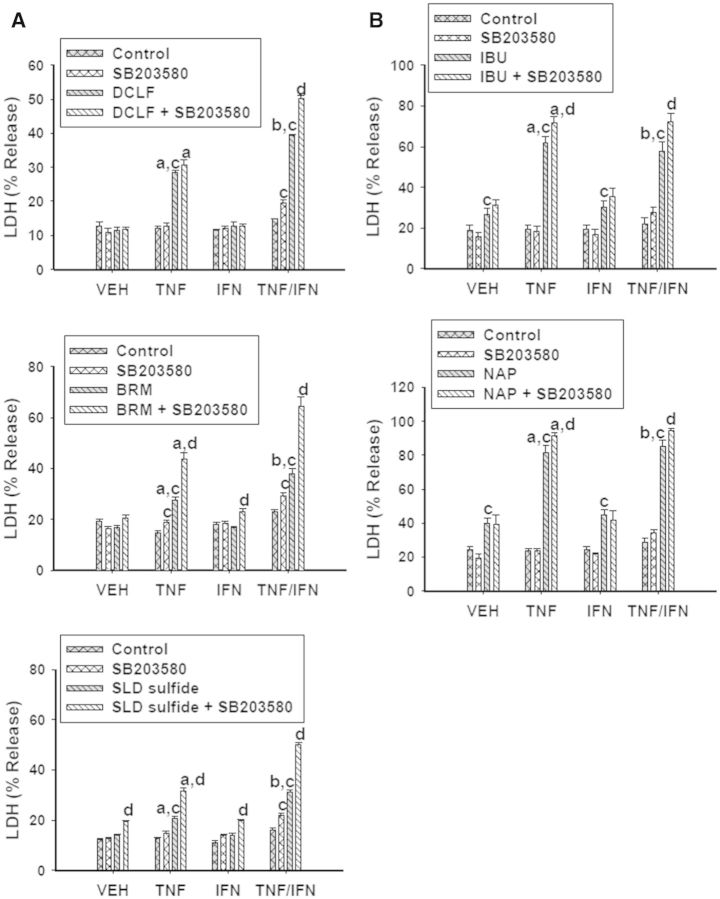

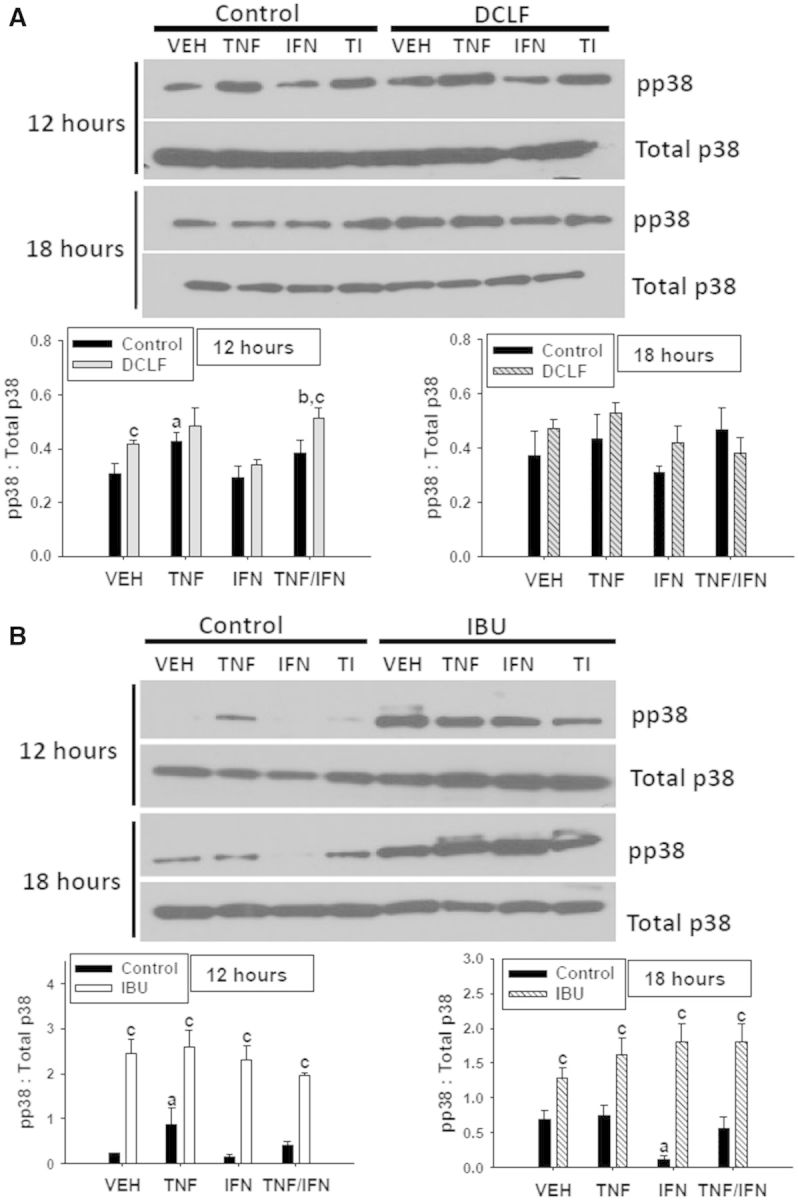

p38 Attenuates NSAID/Cytokine-Induced Cytotoxic Synergy

Treatment with either TNFα alone or DCLF alone induced phosphorylation of p38 at 12 h but not at 18 h (Fig. 8A). There was no change in DCLF-induced p38 activation in the presence of TNFα at 12 h, and treatment with DCLF/TNFα/IFNγ increased p38 phosphorylation relative to DCLF/IFNγ or TNFα/IFNγ treatment (Fig. 8A). IBU strongly induced p38 activation relative to VEH at 12 and 18 h (Fig. 8B). Cytokine treatment did not significantly alter IBU-mediated p38 activation (Fig. 8B).

FIG. 8.

Treatment with TNFα, DCLF or IBU induces activation of p38. HepG2 cells were treated with (A) a representative AA derivative (DCLF: 250 μM) or (B) a representative PA derivative (IBU: 6 mM) alone or in combination with TNFα and/or IFNγ, and protein extracts were collected 12 or 18 h after treatment. pp38 and total p38 protein were detected via western analysis. Representative blots are shown. Densitometry was performed using image J software. a, significantly different from VEH; b, significantly different from IFNγ; c, significantly different from Control. Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M of 3 separate experiments. VEH, vehicle; TNF, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, IFN, interferon-gamma; TI, tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma; DCLF, diclofenac; IBU, ibuprofen.

Activation of p38 is typically associated with activation of pathways leading to cell death. Surprisingly, with the exception of DCLF/TNFα exposure, treatment with the p38 inhibitor SB203580 enhanced cytotoxicity mediated by AA derivative/TNFα exposure in the presence and absence of IFNγ (Fig. 9A). Treatment with SB203580 potentiated cytotoxicity from PA derivative/TNFα exposure as well, irrespective of IFNγ exposure (Fig. 9B). These data suggest that p38 plays a protective role in NSAID/cytokine-induced cytotoxicity.

FIG. 9.

P38 plays a protective role in NSAID/cytokine-induced cytotoxicity. HepG2 cells were treated with (A) AA derivatives (DCLF: 250 µM, BRM: 750 µM or SLD sulfide: 200 μM), or (B) PA derivatives (IBU: 6 mM or NAP: 10 mM) alone or in combination with TNFα and/or IFNγ. NSAID/cytokine combinations were also incubated in the presence and absence of the p38 inhibitor SB203580 (20 μM). Cytotoxicity was measured 24 h later. a, significantly different from VEH within NSAID/inhibitor treatment; b, significantly different from TNFα within NSAID/inhibitor treatment; c, significantly different from Control within a cytokine group; d, significantly different from NSAID without inhibitor within a cytokine group. Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M of at least 4 separate experiments. VEH, vehicle; TNF, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; IFN, interferon-gamma; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; DCLF, diclofenac; BRM, bromfenac; SLD, sulindac; IBU, ibuprofen; NAP, naproxen.

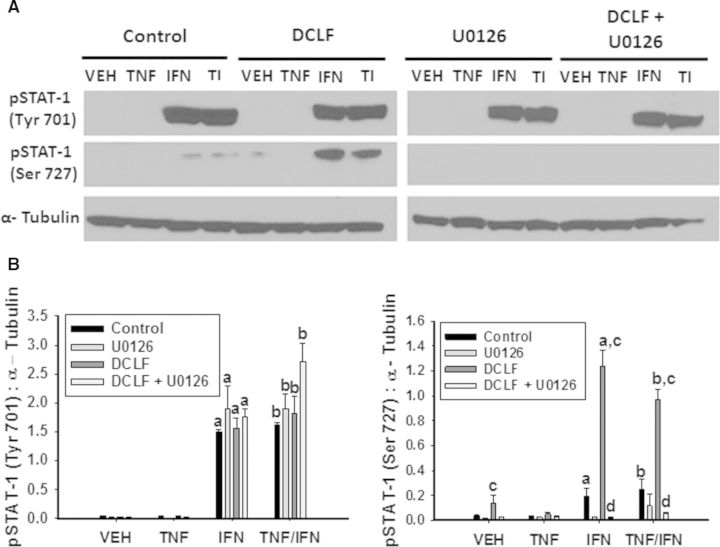

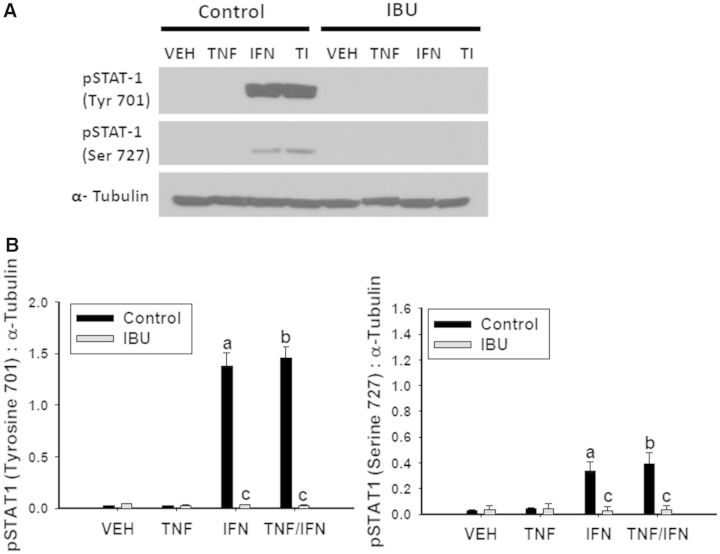

DCLF But Not IBU Promotes Dual Phosphorylation of STAT-1 in an ERK-Dependent Manner

Upon binding to its receptor, IFNγ is well known to activate the JAK-STAT pathway. As expected, treatment with IFNγ resulted in phosphorylation of STAT-1 at tyrosine (Tyr) 701, irrespective of TNFα exposure (Fig. 10). DCLF treatment did not influence Tyr 701 phosphorylation. It has been reported that phosphorylation of STAT-1 at serine (Ser) 727 in addition to Tyr 701 is required for maximal activation (Varinou et al., 2003). There was a modest increase in phosphorylation of STAT-1 at Ser 727 in response to IFNγ treatment, irrespective of TNFα treatment. Interestingly, treatment with DCLF markedly enhanced the IFNγ-mediated phosphorylation at Ser 727 (Fig. 10). JAK is responsible for phosphorylating Tyr 701 on STAT-1. It is unclear which specific kinases are responsible for phosphorylating Ser 727, but it has been suggested that MAPKs, specifically ERK, can perform this phosphorylation (Zhang et al., 2004). Treatment with the ERK inhibitor U0126 did not alter phosphorylation of Tyr 701 but completely prevented phosphorylation of Ser 727 (Fig. 10). Treatment with IBU prevented IFNγ-mediated phosphorylation of STAT-1 at both Tyr 701 and Ser 727 (Fig. 11).

FIG. 10.

DCLF promotes ERK-dependent phosphorylation of STAT-1 in the presence of IFNγ. HepG2 cells were treated with (A) a representative AA derivative (DCLF: 250 μM) alone or in combination with TNFα and/or IFNγ and incubated in the presence or absence of U0126. Protein extracts were collected 18 h after treatment. pSTAT-1 (Tyrosine 701), pSTAT-1 (Serine 727) and α-Tubulin protein levels were detected via western analysis. Representative blots are shown. (B) Densitometry was performed using image J software. a, significantly different from VEH; b, significantly different from TNFα; c, significantly different from Control; d, significantly different from DCLF (without inhibitor). Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M of 3 separate experiments. VEH, vehicle; TNF, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, IFN, interferon-gamma; TI, tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma; DCLF, diclofenac; Tyr, tyrosine; Ser, serine.

FIG. 11.

IBU treatment prevents IFNγ-mediated phosphorylation of STAT-1. HepG2 cells were treated with (A) a representative PA derivative (IBU: 6 mM) alone or in combination with TNFα and/or IFNγ. Protein extracts were collected 18 h after treatment. pSTAT 1 (Tyrosine 701), pSTAT-1 (Serine 727), and α-Tubulin protein levels, were detected via western analysis. Representative blots are shown. (B) Densitometry was performed using image J software. a, significantly different from VEH; b, significantly different from TNFα; c, significantly different from Control. Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M of 3 separate experiments. VEH, vehicle; TNF, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, IFN, interferon-gamma; TI, tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma; IBU, ibuprofen; Tyr, tyrosine; Ser, serine.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that NSAIDs associated with IDILI synergize with TNFα to kill HepG2 cells in vitro and that treatment with an additional cytokine, IFNγ, enhanced the NSAID/TNFα-induced cytotoxic interaction. These results are consistent with what has been reported previously in studies involving animal models of drug/inflammatory stress-induced liver injury (Dugan et al., 2011; Shaw et al., 2009a, b; Zou et al., 2009). The IFNγ-mediated enhancement of NSAID/TNFα-induced cytotoxicity was observed with the AA derivatives (DCLF, BRM, and SLD sulfide) but not with the PA derivatives (IBU or NAP), suggesting that this is a phenomenon related to chemical structure.

To gain insight into the mechanism underlying NSAID/cytokine-induced cytotoxic synergy, the roles of caspases and MAPKs were examined. Caspase enzymes are crucial to the initiation of apoptosis (Porter and Jänicke, 1999), and results of previous studies suggested a role for caspases in drug/cytokine-induced cytotoxic synergy (Beggs et al., 2014; Fredriksson et al., 2011; Zou et al., 2009). Treatment with a representative AA derivative or PA derivative resulted in activation of caspase 3, which was increased further in the presence of TNFα (Fig. 2). Treatment with IFNγ enhanced caspase 3 activation in the presence of DCLF/TNFα but not IBU/TNFα (Fig. 2), consistent with its effect on cytotoxicity (Fig. 1). Treatment with the caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK eliminated the NSAID/TNFα-mediated cytotoxic interaction and also eliminated the IFNγ-mediated enhancement of NSAID/TNFα cytotoxicity (Fig. 3). These results suggest that caspase-mediated apoptosis is the mode of cell death in NSAID/cytokine cytotoxic synergy.

Prolonged activation of JNK is associated with signaling through pathways leading to cell death (Wullaert et al., 2007), and JNK activation contributes to cytotoxicity mediated by TNFα in combination with trovafloxacin, another IDILI-associated drug, and, as mentioned previously, also by DCLF/TNFα (Beggs et al., 2014; Fredriksson et al., 2011). In this study, DCLF and IBU caused similar patterns of JNK activation (Fig. 4). That is, both drugs caused persistent JNK activation that was enhanced in the presence of TNFα but unaffected by IFNγ exposure. A JNK inhibitor eliminated the activation of JNK and completely prevented the cytotoxic synergy caused by DCLF/TNFα in the absence and presence of IFNγ (Fig. 5). This is consistent with IFNγ interacting somehow with the cell death pathway initiated by TNFα. Inhibition of JNK similarly prevented cytotoxicity from other AA derivative NSAID/cytokine combinations (Fig. 5A).

In contrast to the AA derivatives, JNK inhibition did not affect cytotoxicity mediated by PA derivative/cytokine combinations (Fig. 5B). At first glance, these results suggest that JNK plays a role in cytotoxic synergy mediated by AA derivatives but not PA derivatives. However, treatment with the JNK inhibitor did not eliminate phosphorylation of JNK induced by IBU treatment, which might explain the lack of effect on cytotoxicity (Fig. 5C). Moreover, since SP600125 acts as a reversible, ATP-competitive inhibitor (Bennett et al., 2001), it is possible that IBU physically interacts with SP600125 or with JNK, thereby preventing SP600125 from completely inhibiting ATP binding to JNK. Treatments with larger concentrations of SP600125 were attempted but were unsuccessful due to solubility limitations at concentrations >30 μM.

ERK phosphorylation is typically associated with activating cell survival signaling pathways; however, it has become clear that under some conditions, ERK activates cell death pathways (Cagnol and Chambard, 2010). The duration of ERK activation can be an important factor in determining cellular fate. It has been suggested that prolonged ERK signaling can lead to cell death (Cagnol and Chambard, 2010). The involvement of ERK in the cytotoxic synergy mediated by IDILI-associated drugs in combination with cytokines has not been reported previously. The representative AA and PA derivatives induced very similar patterns of ERK activation (Fig. 6), and these were not affected by cytokine treatment. U0126 treatment effectively inhibited both DCLF- and IBU-mediated ERK activation (Fig. 7C) but had opposite effects on the synergistic cytotoxicity caused by AA and PA derivatives. U0126 eliminated the IFNγ-mediated enhancement of AA derivative/TNFα-induced cytotoxicity, suggesting that the cytotoxic effect of IFNγ required ERK activity. In contrast, U0126 treatment potentiated cytotoxicity mediated by the PA derivative/cytokine combinations (Fig. 7B). These results suggest that ERK signaling plays a protective role in this case. Together, the findings indicate that persistent ERK activation can promote either cell survival or cell death, depending on the particular NSAID involved in its activation.

The involvement of p38 in drug/cytokine-induced cytotoxic synergy has not been reported. TNFα transiently activates p38 in a variety of cell types (Anderson, 1997), as was seen here in HepG2 cells (Fig. 8). DCLF also caused a transient activation of p38 that was modestly affected by the addition of cytokines (Fig. 8A). In contrast, IBU caused activation of p38 that was longer lived but unaffected by cytokine treatment (Fig. 8B). The observation that inhibition of p38 enhanced the NSAID/cytokine-induced cytotoxic interaction (Fig. 9) suggests that p38 dampens this toxic response. Although activation of p38 is commonly associated with activation of cell death pathways (Anderson, 1997), it can promote cell survival under certain conditions. For example, transient activation of p38 by TNFα is essential to mediating signals that protect cells from apoptosis (Roulston et al. 1998).

As mentioned earlier, AA and PA derivatives responded differently in terms of their interaction with cytokines to kill cells. Although both subclasses interacted with TNFα to cause cytotoxicity, IFNγ enhanced the synergy from TNFα and AA derivatives but not PA derivatives. This observation raises the questions of how AA derivatives sensitize cells to the harmful effects of IFNγ and why are cells treated with PA derivatives not sensitive to IFNγ. To answer these questions, we evaluated the phosphorylation status of STAT-1, a critical component of the IFNγ signaling pathway. The IFNγ receptor is a heterodimer-associated intracellularly with JAK. When bound to IFNγ, the receptor becomes activated, leading to activation of JAK which phosphorylates STAT-1 at Tyr 701. Upon phosphorylation, STAT-1 dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus, where it binds to specific DNA sequences (Farrar and Schreiber, 1993). Phosphorylation at Ser 727 is required for maximal STAT-1 activation (Varinou et al., 2003). The kinases responsible for phosphorylation at Ser 727 include MAPKs, specifically ERK (Li et al., 2010). IFNγ caused pronounced phosphorylation of STAT-1 at Tyr 701 but had only a modest effect at Ser 727 (Figs. 10 and 11). Conversely, DCLF was without effect on Tyr 701 phosphorylation but in the presence of IFNγ caused a pronounced increase in phosphorylation at Ser 727 which depended on ERK (Fig. 10). These findings might explain why inhibition of ERK prevented the IFNγ-mediated enhancement of DCLF/TNFα-induced cytotoxicity. Interestingly, phosphorylation of STAT-1 at Tyr 701 in response to IFNγ treatment was necessary for robust DCLF-induced phosphorylation of Ser 727. Consistent with this observation, in several cell types phosphorylation at Tyr 701 by JAK was required for Ser 727 phosphorylation (Sadzak et al., 2008).

In stark contrast to DCLF, treatment with IBU prevented IFNγ-mediated phosphorylation of STAT-1 at both Tyr 701 and Ser 727 (Fig. 11). These results are consistent with the observation that IFNγ failed to enhance cytotoxicity mediated by PA derivatives in combination with TNFα. Given that phosphorylation of Ser 727 was dependent on ERK, it is puzzling that both DCLF and IBU treatment induced the same pattern of ERK activation, yet only DCLF led to phosphorylation of Ser 727. Our findings suggest that treatment with DCLF and IFNγ unmasks a substrate for ERK at Ser 727 of STAT-1, which is not available in cells treated with IBU. In addition, the observation that inhibition of ERK increased cytotoxicity from PA derivatives/TNFα treatment suggests that ERK activated by IBU treatment interacts with a cytoprotective substrate rather than one that leads to enhanced cytotoxicity.

In summary, NSAIDs associated with IDILI synergize with TNFα to cause death of HepG2 cells. IFNγ treatment enhances the cytotoxicity mediated by some NSAIDs in the presence of TNFα. Aspirin, an NSAID that is not associated with IDILI, did not synergize with any combination of cytokines to kill cells. These findings raise the possibility that drug/cytokine cytotoxic synergy contributes to human IDILI from NSAIDs.

With regard to mechanism, NSAID/cytokine-induced cytotoxicity requires caspases, suggesting an apoptotic mode of cell death. Persistent JNK activation plays an important role in the cytotoxic synergy. Prolonged ERK activation plays either a cytotoxic or a protective role, depending on NSAID chemical structure, whereas p38 is cytoprotective. Cosgrove et al. (2010) evaluated the signaling pathways involved in drug/cytokine-induced cytotoxic synergy in primary human hepatocytes. They found that various drugs associated with IDILI (including NSAIDs) synergized with cytokines to cause MAPK signaling dysregulation and consequently death of primary human hepatocytes, which lends support to our findings concerning involvement of MAPKs in NSAID/cytokine-induced cytotoxic synergy in HepG2 cells. NSAIDs from different structural classes differentially modify the phosphorylation status of STAT-1, and this appears to explain why IFNγ potentiates the cytotoxic interaction with TNF for some NSAIDs but not others.

These findings suggest that cytotoxic synergy of drugs with cytokines occurs through different kinase signaling mechanisms, even for drugs within the same pharmacologic class, and that these differences are related to chemical structure and IDILI liability. Knowledge generated from this study could be useful in developing an in vitro approach to classify drugs according to their potential to cause IDILI in humans.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at http://toxsci.oxfordjournals.org/.

FUNDING

National Institutes of Health (Grant R01 DK087886) and a Colgate Palmolive Award for Research in Alternative Methods.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jonathan Turkus for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- Aithal G., Watkins P., Andrade R., Larrey D., Molokhia M., Takikawa H., Hunt C., Wilke R., Avigan M., Kaplowitz N., et al. (2011). Case definition and phenotype standardization in drug-induced liver injury. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 89, 806–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P. (1997). Kinase cascades regulating entry into apoptosis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61, 22–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beggs K., Fullerton A., Miyakawa K., Ganey P., Roth R. (2014). Molecular mechanisms of hepatocellular apoptosis induced by trovafloxacin-tumor necrosis factor-alpha interaction. Toxicol. Sci. 137, 91–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett B., Sasaki D., Murray B., O'Leary E., Sakata S., Xu W., Leisten J., Motiwala A., Pierce S., Satoh Y., et al. (2001). SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98, 13681–13686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramlage P., Goldis A. (2008). Bioequivalence study of three ibuprofen formulations after single dose administration in healthy volunteers. BMC Pharmacol. 8, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon R., Eadie M., Curran A., Nolan P., Presneill J. (1986). A new formulation of aspirin: bioavailability and analgesic efficacy in migraine attacks. Cephalalgia 6, 19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagnol S., Chambard J. (2010). ERK and cell death: mechanisms of ERK-induced cell death—apoptosis, autophagy and senescence. FEBS J. 277, 2–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove B., Alexopoulos L., Hang T., Hendriks B., Sorger P., Griffith L., Lauffenburger D. (2010). Cytokine-associated drug toxicity in human hepatocytes is associated with signaling network dysregulation. Mol. Biosyst. 6, 1195–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove B., King B., Hasan M., Alexopoulos L., Farazi P., Hendriks B., Griffith L., Sorger P., Tidor B., Xu J., et al. (2009). Synergistic drug-cytokine induction of hepatocellular death as an in vitro approach for the study of inflammation-associated idiosyncratic drug hepatotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 237, 317–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X., Stachlewitz R., Liguori M., Blomme E., Waring J., Luyendyk J., Maddox J., Ganey P., Roth R. (2006). Modest inflammation enhances diclofenac hepatotoxicity in rats: role of neutrophils and bacterial translocation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 319, 1191–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugan C., Fullerton A., Roth R., Ganey P. (2011). Natural killer cells mediate severe liver injury in a murine model of halothane hepatitis . Toxicol. Sci. 120, 507–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrar M., Schreiber R. (1993). The molecular cell biology of interferon-γ and its receptor. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 11, 571–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksson L., Herpers B., Benedetti G., Matadin Q., Puigvert J., de Bont H., Dragovic S., Vermeulen N., Commandeur J., Danen E., et al. (2011). Diclofenac inhibits tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced nuclear factor-kappaB activation causing synergistic hepatocyte apoptosis. Hepatology 53, 2027–2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Rodriguez L., Williams R., Derby L., Dean A., Jick H. (1994). Acute liver injury associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the role of risk factors. Arch. Intern. Med. 154, 311–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumbhir-Shah K., Cevallos W., DeCleene S., Halstenson C., Korth-Bradley J. (1997). Absolute bioavailability of bromfenac in humans. Ann. Pharmacother. 31, 395–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershey G., Schreiber R. (1989). Biosynthetic analysis of the human interferon-gamma receptor. Identification of N-linked glycosylation intermediates. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 11981–11988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaunig J., Goldblatt P., Hinton D., Lipsky M., Chacko J., Trump B. (1981). Mouse liver cell culture. I. Hepatocyte isolation. In Vitro. 17, 913–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luyendyk James P., Shaw Patrick J., Green Christopher D., Maddox Jane F., Ganey Patricia E., Roth Robert A. (2005). Coagulation-mediated hypoxia and neutrophil-dependent hepatic injury in rats given lipopolysaccharide and ranitidine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. The. 314, 1023–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor N., Dargan P., Jones A. (2003). Hepatocellular damage from non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. QJM 96, 787–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky M., Vincent J., Alegre M., Dupont E. (1993). Serum cytokine levels in human septic shock. Chest 103, 565–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter A., Jänicke R. (1999). Emerging roles of caspase-3 in apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 6, 99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramm S., Mally A. (2013). Role of drug-independent stress factors in liver injury associated with diclofenac intake. Toxicology 312, 83–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid J., Mandrekar S., Carlson E., Harmsen W., Green E., McGovern R., Szabo E., Ames M., Boring D., Limburg P. (2008). Comparative bioavailability of sulindac in capsule and tablet formulations. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 17, 674–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth R., Ganey P. (2011). Animal models of idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury—current status. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 41, 723–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roulston A., Reinhard C., Amiri P., Williams L. (1998). Early activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase and p38 kinase regulate cell survival in response to tumor necrosis factor alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 10232–10239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadzak I., Schiff M., Gattermeier I., Glinitzer R., Sauer I., Saalmüller A., Yang E., Schaljo B., Kovarik P. (2008). Recruitment of Stat1 to chromatin is required for interferon-induced serine phosphorylation of Stat1 transactivation domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 8944–8949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setiawati E., Deniati S., Yunaidi D., Handayani L., Harinanto G., Santosos I., Purnomo, Sari A., Rimainar A. (2009). Bioequivalence study with two naproxen sodium tablet formulations in healthy subjects. J. Bioequiv. Bioavailab. 1, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P., Ganey P., Roth R. (2009a). Tumor necrosis factor alpha is a proximal mediator of synergistic hepatotoxicity from trovafloxacin/lipopolysaccharide coexposure. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 328, 62–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P., Ditewig A., Waring J., Liguori M., Blomme E., Ganey P., Roth R. (2009b). Coexposure of mice to trovafloxacin and lipopolysaccharide, a model of idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity, results in a unique gene expression profile and interferon gamma-dependent liver injury. Toxicol. Sci. 107, 270–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephanou A., Latchman D. (2003). STAT-1: a novel regulator of apoptosis. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 84, 239–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stonāns I., Stonāne E., Russwurm S., Deigner H., Böhm K., Wiederhold M., Jäger L., Reinhart K. (1999). HepG2 human hepatoma cells express multiple cytokine genes. Cytokine 11, 151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taudorf S., Krabbe K., Berg R., Pedersen B., Møller K. (2007). Human models of low-grade inflammation: bolus versus continuous infusion of endotoxin. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 14, 250–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teoh N., Farrell G. (2003). Hepatotoxicity associated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Clin. Liver Dis. 7, 401–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuijos S., Fontana R. (2011). Mechanisms of drug-induced liver injury: from bedside to bench. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 8, 202–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uetrecht J. (1999). New concepts in immunology relevant to idiosyncratic drug reactions: the ‘danger hypothesis’ and innate immune system. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 12, 387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unzueta A., Vargas H. (2013). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced hepatotoxicity . Clin. Liver Dis. 17, 643–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderlinde R. (1985). Measurement of total lactate dehydrogenase activity. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 15, 13–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varinou L., Ramsauer K., Karaghiosoff M., Kolbe T., Müller M., Decker T. (2003). Phosphorylation of the Stat1 transactivation domain is required for full-fledged IFN-gamma-dependent innate immunity. Immunity. 19, 793–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerink W., Schoonen W. (2007a). Cytochrome p450 enzyme levels in HepG2 cells and cryopreserved primary human hepatocytes and their induction in HepG2 cells. Toxicol. In Vitro 21, 1581–1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerink W., Schoonen W. (2007b). Phase II enzyme levels in HepG2 cells and cryopreserved primary human hepatocytes and their induction in HepG2 cells. Toxicol. In Vitro 21, 1592–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wullaert A., Van L., Heyninck K., Beyaert R. (2007). Hepatic tumor necrosis factor signaling and nuclear factor-kappaB: effects on liver homeostasis and beyond. Endocr. Rev. 28, 365–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Henstock P., Dunn M., Smith A., Chabot J., Graff D. (2008). Cellular imaging predictions of clinical drug-induced liver injury. Toxicol. Sci. 105, 97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Cho Y., Peterson B., Zhu F., Dong Z. (2004). Evidence of STAT1 phosphorylation modulated by MAPKs, MEK1 and MSK1. Carcinogenesis 25, 1165–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou W., Beggs K., Sparkenbaugh E., Jones A., Younis H., Roth R., Ganey P. (2009). Sulindac metabolism and synergy with tumor necrosis factor-alpha in a drug-inflammation interaction model of idiosyncratic liver injury. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 331, 114–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.