Abstract

Objective

Identifying positive psychological factors that reduce health care use may lead to innovative efforts that help build a more sustainable and high quality health care system. Prospective studies indicate that life satisfaction is associated with good health behaviors, enhanced health, and longer life, but little information is available about the association between life satisfaction and health care use. We tested whether higher life satisfaction was prospectively associated with fewer doctor visits. We also examined potential interactions between life satisfaction and health behaviors.

Methods

Participants were 6,379 adults from the Health and Retirement Study, a prospective and nationally representative panel study of American adults over the age of 50. Participants were tracked for four years. We analyzed the data using a generalized linear model with a gamma distribution and log link.

Results

Higher life satisfaction was associated with fewer doctor visits. On a six-point life satisfaction scale, each unit increase in life satisfaction was associated with an 11% decrease in doctor visits—after adjusting for sociodemographic factors (RR = 0.89, 95% CI = 0.86 to 0.93). The most satisfied respondents (N=1,121; 17.58%) made 44% fewer doctor visits than the least satisfied (N=182; 2.85%). The association between higher life satisfaction and reduced doctor visits remained even after adjusting for baseline health and a wide range of sociodemographic, psychosocial, and health-related covariates (RR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.93 to 0.99).

Conclusions

Higher life satisfaction is associated with fewer doctor visits, which may have important implications for reducing health care costs.

Keywords: life satisfaction, successful aging, health care utilization, doctor visit, psychological well-being, positive psychology

Sustaining high quality health care is a growing concern for all and an issue prominently featured in national and international debates. In the United States, health care costs are approximately 16% of the country's gross domestic product and expected to almost double in the next decade, reaching 4.6 trillion dollars by 2020 (1). Despite spending more on health care than any other nation, people in the United States have inferior life expectancies and disease profiles, when compared against people in other developed nations (2,3). This disadvantage is not exclusively attributable to disadvantaged and poor Americans, because even very wealthy and educated Americans are in worse health than their counterparts in comparable countries (2,3).

A related issue is the increasing utilization of health care services. The aging population, which uses a continuously increasing number of doctor visits, puts a significant strain on the health care system. High use of health care services by certain segments of the population will not only lead to increased costs but also reduce the quality and timeliness of care for all. Health care use and associated costs have numerous contributors. Among these contributors, researchers have attempted to identify the factors that can be changed without sacrificing quality of care. Of interest have been administrative costs, medical technologies, prescription drugs, hospital care, and addressing physical illnesses and conditions that increase the use and costs of health care in an aging population (4). Psychological problems such as depression have also been examined (5,6). The common focus has been on factors associated with increased health care use, which translates into increased costs.

An alternative strategy is to identify factors associated with decreased health care use and costs. Possible candidates include positive psychological factors such as optimism, positive affect, purpose in life, and life satisfaction, each of which is strongly associated with better health (7-22). However, the link between such positive psychological factors and health care use is unknown. Given that the absence of psychological problems does not indicate the presence of psychological well-being (23), identifying positive psychological factors that reduce health care use may lead to innovative efforts that help build a sustainable and high quality health care system.

Using longitudinal data from the Health and Retirement Study (24,25), the present research examined the link between life satisfaction (sometimes called happiness) and health care use, measured by the number of doctor visits made among older US adults over a four-year period. Life satisfaction is an individual's overall judgment of how well his or her life has been lived. Life satisfaction foreshadows good health, including reduced risk of heart disease and increased longevity (18-20). We hypothesized that higher life satisfaction would predict fewer doctor visits, even when possible confounds such as age, gender, ethnicity, wealth, baseline number of chronic illnesses, frequency of past doctor visits, functional status, and an array of other factors were taken into account. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the association between life satisfaction and healthcare use.

Method

Study Design and Sample

The Health and Retirement Study is an ongoing nationally representative panel study of US adults aged 50 and older, surveying over 22,000 Americans every two years since 1992. The HRS is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) and is conducted by the University of Michigan (24,25). Because this study used de-identified, publicly available data, the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan exempted it from review.

Starting in 2006, HRS began collecting psychosocial measures. That year, approximately 50% of HRS respondents were visited for an enhanced face-to-face interview. These respondents were also asked to complete a self-reported psychosocial questionnaire. The response rate was 90%. During the four-year follow-up, 789 out of 7,168 respondents passed away and were dropped from the analyses. The final sample consisted of 6,379 respondents. Sensitivity analyses were run to examine the impact of dropping deceased respondents. Whether the deceased were included or excluded, the relationship between life satisfaction and doctor visits remained significant. Therefore, data that excluded deceased respondents was used.

Life Satisfaction

In 2006, life satisfaction was assessed using the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) (26). Respondents were asked to rate each of five items on a 6-point Likert scale, indicating the degree to which they endorsed statements such as “In most ways my life is close to ideal” (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree). All five items were averaged for a final score. The Satisfaction with Life Scale has excellent psychometric properties (26). The original SWLS uses a 7-point Likert scale, but several psychosocial scales in HRS were converted into 6-point scales to standardize and streamline measures. The average life satisfaction among respondents in the present study was 4.41 (SD = 1.19), and the reliability of the scale was excellent (α = 0.90).

Doctor Visits Measurement

In 2004, 2006, 2008, and 2010, respondents were asked: “Aside from any hospital stays or outpatient surgery, how many times have you seen or talked to a medical doctor about your health, including emergency room or clinic visits in the last two years?” The same HRS item has been used to measure the frequency of doctor visits in other studies (27). The validity of using self-report as an accurate estimate of doctor visits has been shown. Self-reported doctor visits shows substantial agreement with both administrative claims and medical records (28-31).

Doctor visit reports from the 2004 and 2006 waves were summed to cover a four-year period spanning from 2002 to 2006 (X = 18.15, SD = 23.29). Doctor visit reports from the 2008 and 2010 waves were summed to cover a four-year period spanning from 2006 to 2010 (X = 20.42, SD = 24.10). The 2006-2010 composite was the dependent measure in the present study, and the 2002-2006 composite was used as a baseline covariate.

Baseline Covariates

Baseline covariates were assessed in 2006. Potential confounds of the association between life satisfaction and frequency of doctor visits included relevant sociodemographic, psychosocial, and health-related risk factors.

Sociodemographic covariates included age, gender, race/ethnicity (European-American, African-American, Hispanic, other), marital status (married/not married), educational attainment (no degree, GED or high school diploma, college degree or higher), and total wealth (<25,000; 25,000-124,999; 125,000-299,999; 300,000-649,999; >650,000—based on quintiles of the score distribution in this sample).

Psychosocial covariates included both negative (anxiety and depression) and positive (optimism and social integration) psychosocial factors. Further information about these psychosocial measures can be found in the HRS Psychosocial Manual: http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/userg/HRS2006-2010SAQdoc.pdf.

Health-related covariates included smoking status (never, former, current), frequency of moderate (e.g., gardening, dancing, walking at a moderate pace) and vigorous exercise (e.g., running, swimming, aerobics) (never, 1-4 times per month, more than once a week), frequency of alcohol consumption (abstinent, less than 1 or 2 days per month, 1 to 2 days per week, and more than 3 days per week), number of previous doctor visits between 2002 and 2006 (as just explained), health insurance status (yes/no), functional status (number of activities of daily living performed with difficulty: bathing, eating, dressing), and an index of major chronic illnesses.

For the chronic illness index, self-report of a doctor's diagnosis of eight major medical conditions were recorded at baseline: (1) high blood pressure, (2) diabetes, (3) cancer or malignant tumor of any kind, (4) lung disease, (5) heart attack, coronary heart disease, angina, congestive heart failure, or other heart problems, (6) emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems, (7) arthritis or rheumatism, and 8) stroke. Respondents reported an average of 1.96 (SD=1.37) conditions. Self-reported health measures used in HRS have been rigorously assessed for their validity and reliability (24, 25).

Statistical Analyses

Because the number of doctor visits had a skewed distribution, we analyzed the data using a generalized linear model with a gamma distribution and log link, rather than using an ordinary least squares regression (32). The Box Cox, Modified Park, Pregibon's Link, and Hosmer-Lemeshow tests were used as diagnostic and goodness of fit measures. Due to the non-linear nature of the model, the estimated β coefficients were not directly interpretable. In order to obtain more easily interpretable results, the gamma coefficients created by the model were exponentiated into rate ratio (RR) estimates using the eform command in Stata (StataCorp. 2011. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). The model was weighted in Stata using HRS sampling weights to account for the complex multistage probability survey design (e.g., non-response, sample clustering, stratification, further post-stratification).

In order to simultaneously address the large number of covariates and avoid over-fitting the models, we examined the impact of the risk factors by creating a core model (Model 1) and then considered the impact of related covariates in turn. A total of four models were created. Model 1, the core model, adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, education level, and total wealth; Model 2 – core model + psychosocial factors (depression, anxiety, optimism, and social integration); and Model 3 – core model + health related factors (smoking, exercise, alcohol use, number of previous doctor visits, insurance, index of major chronic illnesses, and functional status). Although doing so could overfit the model and raise multicollinearity issues, we also created a Model 4, which included all 17 covariates.

Prior research suggests that the association between life satisfaction and doctor visits varies by degree of engagement in various health behaviors, a potential effect modification. Therefore, we tested for potential interactions by creating interaction terms between life satisfaction and three health behaviors: smoking status, frequency of alcohol use, and frequency of exercise. All three health behaviors were dummy coded with abstention from an activity (e.g., no smoking, no alcohol intake, no exercise) as the reference group. The appropriate variables were mean centered in order to reduce multicollinearity problems. We also tested for a threshold effect. Life satisfaction scores were categorized into low (life satisfaction scores ranging from 1-3) and high (life satisfaction scores ranging from 4-6) based on the graph displaying the number of doctor visits as function of life satisfaction scores.

Finally, we examined if the association between life satisfaction and frequency of doctor visits differed if people suffered from a low versus high number of chronic diseases. Based on cutoff scores set by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Strategic Framework on Multiple Chronic Conditions, people were grouped into either a low chronic disease subgroup (zero or one chronic illness) or high chronic disease subgroup (two or more chronic illnesses).

Missing Data and Sensitivity Analyses

For all study variables, the overall item non-response rate was 1.71%. However, the missing data were scattered throughout the variables and resulted in a 25.69% loss of respondents when analyses with list-wise deletion was attempted. Therefore, to obtain less biased estimates, multiple imputation procedures were used to impute missing data. Sensitivity analyses showed that the results were significant before and after the implementation of multiple imputations. We therefore used the dataset with multiple imputation for all analyses reported here because this technique provides a more accurate estimate of association than other methods of handling missing data. Age, gender, race, index of chronic illnesses, marital status, total wealth, and functional status were used for the multiple imputation procedure. Further sensitivity analyses were conducted by excluding respondents at the two extremes of doctor visits—those who visited doctors the most (top 5%) and the least (bottom 5%). Again, results were significant whether the extreme respondents were included or excluded. Therefore, the imputed data without the exclusion of extremes was used.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The average age of respondents at baseline was 68 years (SD = 9.39). Respondents tended to be female (59%), European-American (78%), and married (66%). Most had a high school degree (55%) or attended some college (27%). Wealth varied, as would be expected. More than 95% had health insurance. About 43% of respondents had never smoked, and 42% were former smokers. Only 24% reported that they exercised at least weekly, whereas 61% reported that they never exercised. About 47% never consumed alcohol, and 18% did so no more than one day per week. Table 1 shows all of the descriptive statistics.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics (n= 6,379).

| % or Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Age | 67.99 (9.39) |

| Female | 59.07% |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 77.69% |

| African-American | 13.12% |

| Hispanic | 7.61% |

| Other | 1.58% |

| Married Status | 66.19% |

| Education | |

| < High School | 17.70% |

| High School | 55.09% |

| ≥ College | 27.21% |

| Total Wealth | |

| 1st Quintile | 15.55% |

| 2nd Quintile | 18.04% |

| 3rd Quintile | 21.67% |

| 4th Quintile | 21.89% |

| 5th Quintile | 22.84% |

| Depression | 1.34 (1.88) |

| Anxiety | 1.55 (0.56) |

| Optimism | 4.56 (1.14) |

| Social Integration | 2.74 (1.71) |

| Smoking Status | |

| Never | 43.35% |

| Former Smoker | 42.38% |

| Current Smoker | 12.26% |

| Exercise | |

| Never | 60.54% |

| 1-4 times per month | 15.11% |

| More than 1x per week | 24.36% |

| Alcohol Frequency (days/week) | |

| Never | 47.32% |

| <1 | 18.44% |

| 1-2 | 16.51% |

| 3+ | 17.73% |

| # of Previous Doctor Visits | 18.15 (23.29) |

| Insured | 95.27% |

| Index of Chronic Illnesses | 1.96 (1.37) |

| Functional Status | 3.88 (0.43) |

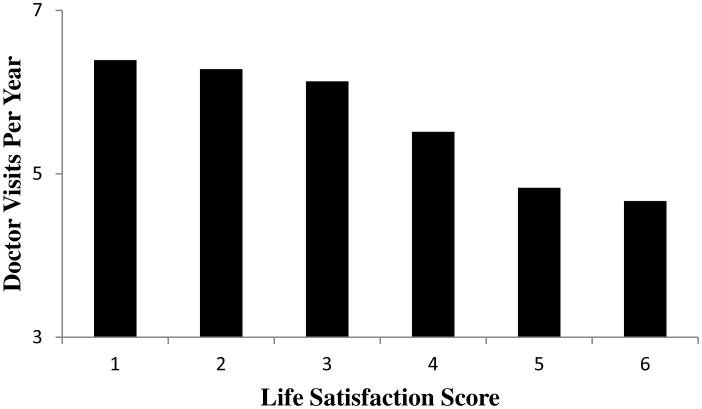

On a scale ranging from 1 to 6, the average life satisfaction score was 4.41 (SD = 1.19). Life satisfaction scores were distributed in the following manner: “1” (2.85%, n=182), “2” (6.37%, n=406), “3” (11.44%, n=730), “4” (23.05%, n=1,471), “5” (38.71%, n=2,469), and “6” (17.58%, n=1,121). Furthermore, Supplemental Table 1 shows the correlations among the continuous factors in the study and Supplemental Table 2 shows the distribution of life satisfaction scores among the categorical factors. Finally, in unadjusted analyses, the average number of doctor visits (per year) among people who reported the highest life satisfaction was 4.64 compared to an average 6.39 visits among people who reported the lowest life satisfaction (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Number of doctor visits from 2006 to 2010 as a function of the 2006 life satisfaction score (N = 6,379), unadjusted for covariates.

Life Satisfaction and the Number of Doctor Visits

People with higher life satisfaction made fewer doctor visits than those with lower life satisfaction (RR = 0.89, 95% CI = 0.86 to 0.93; p < .001) in the core model (Model 1, Table 2). Each unit increase in life satisfaction was associated with a 10.57% reduction in the number of reported doctor visits over the four-year follow-up. In this model, respondents reporting the highest life satisfaction made 44.16% fewer doctor visits than those reporting the lowest life satisfaction.

Table 2. Association Between Life Satisfaction and Doctor Visitsa (n= 6,379).

| Model | Covariates | Adjusted RR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Core sociodemographic factors* | 0.894 (0.864-0.925) | < 0.001 |

| 2 | Demographic* + psychosocial factors† | 0.932 (0.898-0.967) | < 0.001 |

| 3 | Demographic* + health related factors‡ | 0.961 (0.931-0.993) | 0.018 |

| 4 | All covariates§ | 0.964 (0.930-0.994) | 0.043 |

Core sociodemographic factors: age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, education level, total wealth

Psychosocial factors: depression, anxiety, optimism, social integration

Health related factors: smoking, exercise, alcohol use, number of previous doctor visits, insurance, index of major chronic illnesses, functional status

All covariates: age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, education level, total wealth, depression, anxiety, optimism, social integration, smoking, exercise, alcohol use, number of previous doctor visits, insurance, index of major chronic illnesses, functional status

These are results from generalized linear models that used a gamma distribution and log link

Even after adjusting for all 17 covariates (Model 4, Table 2), each unit increase in life satisfaction was associated with a 3.6% reduction in the number of reported doctor visits. In this fully-adjusted model, people reporting the highest life satisfaction made 18.46% fewer doctor visits than those reporting the lowest life satisfaction. As expected, older individuals made more visits (RR = 1.01, 95% CI = 1.00 to 1.01; p=.003), as did those with more chronic illnesses (RR = 1.12, 95% CI = 1.09 to 1.15; p < .001), those with higher depression (RR = 1.02, 95% CI = 1.00 to 1.04; p=.047), and those who visited doctors more frequently in the past (RR = 1.02, 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.02; p < .001). Also, African-American respondents (RR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.80 to 0.95; p=.003) made fewer visits. None of the other covariates predicted doctor visit frequency, which does not mean that they are unimportant in and of themselves but that their independent effects were not apparent when other predictors were controlled in the model.

Interactions Between Life Satisfaction and Health Behaviors

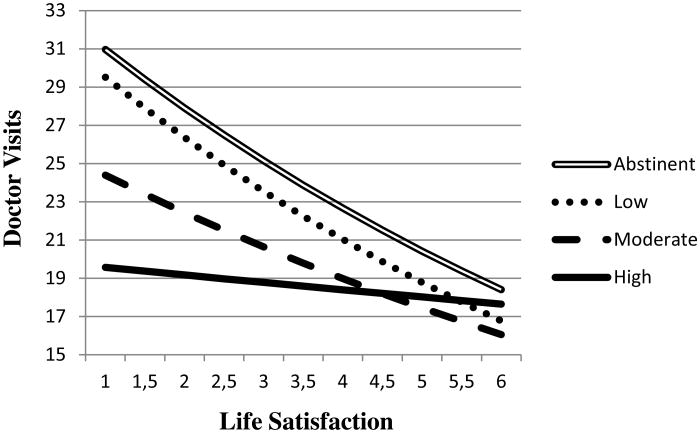

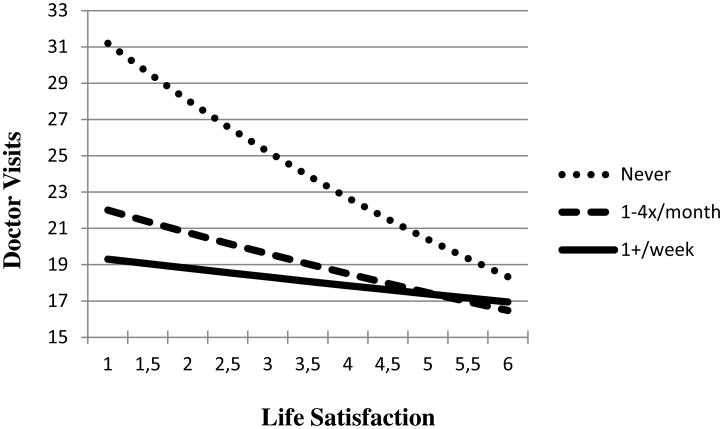

To examine if the effects of life satisfaction on the number of doctor visits varied by degree of engagement in various health behaviors, we examined the interaction between life satisfaction and three behaviors: smoking status, frequency of alcohol use, and frequency of exercise. While the interaction term was not significant for smoking, the interaction term was significant for frequency of alcohol use and frequency of exercise.

The interaction term between life satisfaction and drinking frequency showed that among people who drank the most alcohol, the magnitude of the effect life satisfaction had on doctor visits was almost non-existent (p=.035). However, all other subgroups of drinkers (including those who abstain from drinking) showed a strong and clear relationship between higher life satisfaction and fewer doctor visits (Figure 2). Furthermore, higher life satisfaction was associated with fewer doctor visits only among the subgroup of adults who did not exercise (Figure 3). For people who performed any amount of exercise, life satisfaction did not appear to be linked with frequency of doctor visits.

Figure 2. Number of doctor visits from 2006 to 2010 as a function of the interaction between life satisfaction and alcohol frequency (N = 6,379).

Figure 3. Number of doctor visits from 2006 to 2010 as a function of the interaction between life satisfaction and exercise (N = 6,379).

Subgroup Analyses by Level of Life Satisfaction

We tested for a possible threshold effect. Life satisfaction scores were categorized into low (scores ranging from 1-3) and high (scores ranging from 4-6) based on the graph displaying the number of doctor visits as function of life satisfaction scores (Figure 1). Subgroup analyses showed that life satisfaction was associated with frequency of doctor visits only in the high life satisfaction group (scores ranging from 4-6; RR = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.87 to 0.95; p < .001 – Model 1, Supplemental Table 3). In contrast, life satisfaction was not associated with frequency of doctor visits in the low life satisfaction group (scores ranging from 1-3; RR = 1.03, 95% CI = 0.91 to 1.17; p = .62 – Model 1, Supplemental Table 3). Supplemental Table 3 shows results from all of the models for both subgroups.

Subgroup Analyses by High Versus Low Chronic Disease Status

Based on cutoff scores set by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, people were grouped into either a low (less than two chronic illnesses) or high chronic disease subgroup (two or more chronic illnesses). The same four covariate models that were used in our main analyses were used in these analyses. However, the index of chronic illnesses was removed from the list of covariates because it was the variable we were dividing the sample by.

While the association between life satisfaction and doctor visits remained significant in all models for the low chronic disease subgroup, the association was insignificant in the fully adjusted model for the high chronic disease subgroup (RR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.94 to 1.00; p = 0.079, Supplemental Model 4, Table 4). Furthermore, in every model, the magnitude of the association between life satisfaction and doctor visits was larger in the low chronic disease subgroup when compared against the high chronic disease subgroup. Supplemental Table 4 shows results from all of the models for both subgroups. In an exploratory manner, we attempted different cutoff points and found that as we increased the number of chronic diseases required to place into the high chronic disease subgroup, the association between life satisfaction and doctor visits decreased in a monotonic fashion (data not shown).

Discussion

The current study investigated the prospective association between life satisfaction and frequency of doctor visits in a nationally representative sample of older U.S. adults. People with higher life satisfaction made fewer doctor visits than their less satisfied counterparts, even after controlling for likely confounds, including baseline number of chronic illnesses, frequency of past doctor visits, functional status, and an array of other possible factors. The association between life satisfaction and doctor visits held regardless of how healthy or ill respondents were at baseline. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the association between life satisfaction and health care use.

Why is life satisfaction linked with fewer doctor visits among older US adults? Satisfied adults may visit doctors less frequently because they are healthier, the result of being more socially engaged and supported, having more realistic goals, possessing a greater sense of meaning and purpose, having better health-promoting habits, and managing their existing health problems more effectively (33,34). For example, at baseline in 2006, satisfied respondents were more likely to report psychological, behavioral, and social resources associated with well-being, such as higher optimism (r = .34, p < .001), lower depression (r = -.37, p < .001), greater social integration (r = .12, p < .001, better functional status (r = .13, p < .001), more wealth (r = .24, p < .001), and intact marriages (r = .17, p < .001); they were also more likely to exercise (r = .13, p < .001) and less likely to smoke (r = -.09, p < .001). We controlled for these covariates in predicting subsequent doctor visits from baseline life satisfaction, meaning that they did not fully explain why those who are satisfied visit doctors less frequently. However, the pattern of cross-sectional correlations at baseline underscores the variety of assets to which life satisfaction might be linked. Also, dissatisfied adults may visit doctors more frequently not only because they are less healthy, but also because they are inappropriately worried about their health status, leading to overtreatment and wasteful care (35). For example, in 2006, less satisfied respondents reported higher levels of general anxiety (r = -.31, p < .001).

To examine if the association between life satisfaction and frequency of doctor visits varied by degree of engagement in various health behaviors, we examined the interaction between life satisfaction and three health behaviors: smoking status, frequency of alcohol use, and frequency of exercise. While the interaction term was not significant for smoking, the interaction term was significant for frequency of alcohol use and frequency of exercise.

Interaction analyses revealed that the relationship between life satisfaction and doctor visits was weaker in certain subgroups. For example, the association between life satisfaction and doctor visits was almost non-existent among people who drank alcohol excessively. A possible reason for this finding is that older adults who drink frequently tend to ignore symptoms of disease, visiting doctors only when the disease moves onto advanced stages (36). However, besides the subgroup of people who drank alcohol excessively, a strong and clear relationship existed between higher life satisfaction and fewer doctor visits. Furthermore, in line with past research, people who abstained from drinking visited doctors the most frequently and people who drank the most alcohol visited doctors the least frequently (37,38). Another subgroup where the relationship between life satisfaction and doctor visits did not exist was in people who performed any type of exercise. On the other hand, higher life satisfaction was associated with fewer doctor visits among adults that did not exercise. This observation should be further examined in future research.

Another set of analyses revealed that life satisfaction was associated with frequency of doctor visits only in the high life satisfaction group (scores ranging from 4-6) and not in the low life satisfaction group (scores ranging from 1-3). This result was initially counter-intuitive because past research shows that psychological problems, such as depression, are linked with increased health care use (5,6). Therefore, we expected that the association between increased life satisfaction and reduced doctor visits would be particularly strong in the low life satisfaction group because we hypothesized that each unit increase in life satisfaction would be more beneficial for people who have lower levels of life satisfaction.

The absence of psychological problems, however, does not indicate the presence of psychological well-being (23). In this sample, the correlation between life satisfaction and depression was moderate (r = -.37, p < .001). Furthermore, positive psychological factors and psychological problems show distinct biological correlates (23). Recent research has also shown that positive psychological factors (e.g., optimism, positive affect, and life satisfaction) show strong and unique relationships with enhanced health, even after adjusting for an array of risk factors and psychological problems (7-22). These findings help explain why life satisfaction was associated with frequency of doctor visits only in the high life satisfaction group and not in the low life satisfaction group. Currently, researchers suggest that alleviating psychological problems will reduce health care use. This particular finding suggests that above and beyond alleviating psychological problems, boosting psychological well-being will also reduce health care use.

Further subgroup analyses were conducted. Based on cutoff scores set by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, people were grouped into either a low or high chronic disease subgroup. Analyses revealed that in every model, the magnitude of the association between life satisfaction and doctor visits was larger in the low chronic disease subgroup when compared against people in the high chronic disease subgroup. In an exploratory manner, we also tried different cutoff points and found that as we increased the number of chronic illnesses required to place into the high chronic disease subgroup, the association between life satisfaction and doctor visits decreased. These preliminary findings suggest that sicker patients will continue seeking appropriate medical care irrespective of their level of life satisfaction. Therefore, it does not appear like people skip necessary doctor visits simply because they have high life satisfaction. However, these are preliminary results and more research is needed in this area. Future research should pinpoint the subgroups of people who do and do not show an association between life satisfaction and doctor visits.

Two sets of analyses in this study may appear contradictory, but they are not. In one set of analyses, the results showed that the association between life satisfaction and doctor visits was significant even after adjusting for the baseline number of chronic illnesses. In a later set of subgroup analyses, the association between life satisfaction and doctor visits was stronger among people with zero or one chronic illness (when compared against people with two or more chronic illnesses). Though these two analyses can be perceived as contradictory, showing that an association remains significant even after controlling for a covariate, does not preclude the possibility of an interaction effect (which the subgroup analyses revealed).

This study has limitations. Due to the structure of HRS data, we were unable to examine the types of doctor visits nor the possibility that individuals with higher life satisfaction made fewer but more expensive doctor visits. This possibility seems unlikely, given that higher life satisfaction has been linked with an array of health promoting habits and better health outcomes (18-20,33). Further studies examining the types of doctor visits as a function of life satisfaction are needed. Also, doctor visits were assessed using self-reported data. The validity of self-reported doctor visits has been supported in past research—the data show high agreement between self-reported doctor visits and medical records/administrative claims (28-31). Still, further research that uses objective measures of doctor visits would fine-tune the present findings.

Furthermore, each unit increase in life satisfaction was associated with a 10.57% decrease in doctor visits in the core model; in the fully adjusted model, which controlled for all 17 covariates, the decrease was 3.6%. Despite the seemingly small effect size, these findings should not be overlooked for three reasons. First, the analyses showed that life satisfaction was associated with fewer doctor visits even after controlling for an extensive array of covariates. Given the large number of covariates, the results most likely underestimate the true association between life satisfaction and doctor visits because several of the covariates may serve as mechanisms by which life satisfaction is associated with doctor visits. For example, people with higher life satisfaction may visit the doctor less frequently, because they engage in better health behaviors (e.g., people with higher satisfaction smoke less, exercise more, drink alcohol in moderation), yet we controlled for these variables (33).

Second, there are many cases where small effect sizes translate into meaningful outcomes. Therefore, it is important to interpret findings based on how constructs operate in the real world and also examine if these effects are cumulative across a person's lifespan (39,40). The effects of life satisfaction on doctor visits is cumulative when we consider how life satisfaction can potentially reduce the number of doctor visits over an individual's lifetime, and when the number of doctor visits is aggregated at the population level.

Third, the medical literature provides numerous examples of interventions that show only a modest association with improved health, but save many lives at the population level—which lead to significant changes in the standard of care. For example, although the association between aspirin consumption and the risk of myocardial infarction is only -.03 (smaller than the associations found in this study), one representative study found that aspirin consumption resulted in 85 fewer myocardial infarctions among the patients of 10,845 physicians (41). Aspirin is now routinely recommended for people at high risk for heart attacks. Similarly, even small increases in life satisfaction may yield substantial population-level decreases in healthcare use and free up doctors so that they can care for those most in need of immediate medical attention.

Life satisfaction can and does change (42,43), and several small-scale interventions have been shown to reliably and meaningfully raise it (e.g. 44-46). More research, however, needs to examine if interventions that raise life satisfaction can be feasibly disseminated widely at the population level. Based on the mounting observational evidence linking different facets of psychological well-being with enhanced physical health, researchers have conducted randomized controlled trials that aimed to induce positive affect (a distinct but overlapping factor). Results from these studies show that inducing positive affect can successfully change crucial health behaviors, such as increased medication adherence and physical activity, in chronic disease patients (47-49). However, these studies did not assess if these enhanced health behaviors led to decreased doctor visits.

Successfully addressing the problem of rising medical costs will likely require a multi-faceted approach. We hope the preliminary findings in this study, combined with past studies linking life satisfaction with enhanced health behaviors, improved health, and longer life, will spark new conversations about the possible links between psychological well-being and healthcare use. Further investigation in this line of research may reveal innovative ways of containing healthcare costs.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1: Correlation Table of All Continuous Variables

Supplementary Table 2. Distribution of Life Satisfaction Scores Among All Categorical Variables

Supplementary Table 3: Association Between Life Satisfaction and Doctor Visits By Subgroup

Supplementary Table 4: Association Between Life Satisfaction and Doctor Visits By Chronic Disease Status

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Brady T. West and Richard Gonzalez for their advice on statistical analyses. We also thank Susanne Wurm, Clemens Tesch-Romer, and members of the German Centre of Gerontology for their helpful comments and suggestions. We also acknowledge the Health and Retirement Study, which is conducted by the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan, with grants from the National Institute on Aging (U01AG09740) and the Social Security Administration. Finally, we would like to thank the editor, associate editor, and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Sources of Funding: Support for this publication is provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's Pioneer Portfolio, which supports innovative ideas that may lead to breakthroughs in the future of health and health care. The Pioneer Portfolio funding was administered through a Positive Health grant to the Positive Psychology Center of the University of Pennsylvania, Martin Seligman, director.

Role of the Sponsor: The funding sources had no influence on the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Eric S. Kim had full access to all data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors contributed to the design of the study and interpretation of the findings, and have read, commented on, and approved the manuscript.

Glossary

- HRS

Health and Retirement Study

Footnotes

Disclosures: There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Keehan SP, Sisko AM, Truffer CJ, Poisal JA, Cuckler GA, Madison AJ, Lizonitz JM, Smith SD. National health spending projections through 2020: economic recovery and reform drive faster spending growth. Health Aff (Milwood) 2011;30:1594–605. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woolf SH, Aron L. US health in international perspective: shorter lives, poorer health. Washington D.C.: National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banks J, Marmot M, Oldfield Z, Smith JP. Disease and disadvantage in the United States and England. JAMA. 2006;295:2037–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beamesderfer A, Ranji U. U S health care costs. Menlo Park: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luppa M, Heinrich S, Angermeyer MC, König HH, Riedel-Heller SG. Cost-of-illness studies of depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2007;98:29–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katon WJ. Clinical and health services relationships between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:216–26. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seligman MEP. Positive health. Appl Psychol-Int Rev. 2008;57:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chida Y, Steptoe A. Positive psychological well-being and mortality: a quantitative review of prospective observational studies. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:741–56. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31818105ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rasmussen HN, Scheier MF, Greenhouse JB. Optimism and physical health: a meta-analytic review. Ann Behav Med. 2009;37:239–56. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9111-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boehm JK, Williams DR, Rimm EB, Ryff EB, Kubzansky LD. Association between optimism and serum antioxidants in the Midlife in the United States Study. Psychosom Med. 2013;75:2–10. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31827c08a9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peterson C, Park N, Kim ES. Can optimism decrease the risk of illness and disease among the elderly? Aging Health. 2012;8:5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rozanski A, Kubansky LD. Psychologic functioning and physical health: a paradigm of flexibility. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(Suppl 1):S47–53. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000164253.69550.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen S, Alper CM, Doyle WJ, Treanor JJ, Turner RB. Positive emotional style predicts resistance to illness after experimental exposure to rhinovirus or influenza a virus. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:809–15. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000245867.92364.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyle PA, Barnes LL, Buchman AS, Bennett DA. Purpose in life is associated with mortality among community-dwelling older persons. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:574–9. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181a5a7c0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim ES, Sun JK, Park N, Peterson C. Purpose in life and reduced incidence of stroke in older adults: the Health and Retirement Study. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74:427–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobau R, Seligman ME, Peterson C, Diener E, Zack MM, Chapman D, Thompson W. Mental health promotion in public health: perspectives and strategies from positive psychology. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:e1–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen S, Pressman SD. Does positive affect influence health? Psychol Bull. 2006;131:925–71. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boehm JK, Peterson C, Kivimaki M, Kubzansky LD. Heart health when life is satisfying: evidence from the Whitehall II Cohort Study. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2672–7. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diener E, Chan MY. Happy people live longer: subjective well-being contributes to health and longevity. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2011;3:1–43. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koivumaa-Honkanen H, Honkanen R, Viinamäki H, Heikkilä K, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M. Self-reported life satisfaction and 20-year mortality in healthy Finnish adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:983–91. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.10.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steptoe A, Wardle J. Positive affect measured using ecological momentary assessment and survival in older men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;8:18244–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110892108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howell RT, Kern ML, Lyubormirsky S. Health benefits: meta-analytically determining the impact of well-being on objective health outcomes. Health Psychol Rev. 2007;1:83–136. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryff CD, Dienberg Love G, Urry HL, Muller D, Rosenkranz MA, Friedman EM, Davidson RJ, Singer B. Psychological well-being and ill-being: do they have distinct or mirrored biological correlates? Psychother Psychosom. 2006;75:85–95. doi: 10.1159/000090892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wallace RB, Herzog AR. Overview of the health measures in the Health and Retirement Study. J Hum Resour. 1995;30:S84–S107. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ann Arbor, MI: 2013. Health and Retirement Study, (HRS Data Files; 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010) public use dataset. Produced and distributed by the University of Michigan with funding from the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49:71–5. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McWilliams JM, Meara E, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Use of health services by previously uninsured medicare beneficiaries. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:143–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa067712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cleary PD, Jette AM. The validity of self-reported physician utilization measures. Med Care. 1984;l22:796–803. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198409000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ritter PL, Stewart AL, Kaymaz H, Sobel DS, Block DA, Lorig KR. Self-reports of health care utilization compared to provider records. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:136–41. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00261-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reijneveld SA, Stronks K. The validity of self-reported use of health care across socioeconomic strata: a comparison of survey and registration data. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:1407–14. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.6.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weissman JS, Levin K, Chasan-Taber S, Massagli MP, Seage GR, 3rd, Scampini L. The validity of self-reported health-care utilization by AIDS patients. AIDS. 1996;10:775–83. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199606001-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCulloch CE, Searle SR, Neuhaus JM. Generalized, linear, and mixed models. Hoboken: Wiley; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strine TW, Chapman DP, Balluz LS, Moriarty DG, Mokdad AH. The associations between life satisfaction and health-related quality of life, chronic illness, and health behaviors among U.S. community-dwelling adults. J Community Health. 2008;33:40–50. doi: 10.1007/s10900-007-9066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rasmussen HN, Wrosch C, Scheier MF, Carver CS. Self-regulation processes and health: the importance of optimism and goal adjustment. J Pers. 2006;74:1721–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barsky AJ. Worried sick: our troubled quest for wellness. New York: Little, Brown and Co.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hunkeler EM, Hung YY, Rice DP, Weisner C, Hu T. Alcohol consumption patterns and health care costs in an HMO. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;64:181–90. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baumeister SE, Schumann A, Nakazono TT, Alte D, Friedrich N, John U, Völzke H. Alcohol consumption and out-patient services utilization by abstainers and drinkers. Addiction. 2006;101:1285–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jenkins KR, Zucker RA. The prospective relationship between binge drinking and physician visits among older adults. J Aging Health. 2010;22:1099–113. doi: 10.1177/0898264310376539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abelson RP. A variance explanation paradox: when a little is a lot. Psychol Bull. 1985;97:129–33. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roberts B, Kuncel NR, Shiner R, Caspi A, Goldberg LR. The power of personality: the comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2007;2:313–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00047.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenthal R. Effect sizes in behavioral and biomedical research In: Bickman L, editor Validity and social experimentation: Don Campbell's legacy. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2000. pp. 121–39. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lucas RE, Donnellan MB. How stable is happiness? Using the STARTS model to estimate the stability of life satisfaction. J Res Pers. 2007;41:1091–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Diener E, Lucas RE, Scollon CN. Beyond the hedonic treadmill: revising the adaptation theory of well-being. Am Psychol. 2006;61:305–314. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peterson JC, Charlson ME, Hoffman Z, Wells MT, Wong SC, Hollenberg JP, Jobe JB, Boschert KA, Isen AM, Allegrante JP. A randomized controlled trial of positive-affect induction to promote physical activity after percutaneous coronary intervention. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:329–336. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ogedegbe GO, Boutin-Foster C, Wells MT, Allegrante JP, Isen AM, Jobe JB, Charlson ME. A randomized controlled trial of positive-affect intervention and medication adherence in hypertensive African Americans. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:322–326. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mancuso CA, Choi TN, Westermann H, Wenderoth S, Hollenberg JP, Wells MT, Isen AM, Jobe JB, Allegrante JP, Charlson ME. Increasing physical activity in patients with asthma through positive affect and self-affirmation: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:337–343. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fredrickson BL, Cohn MA, Coffey KA, Pek J, Finkel SM. Open hearts build lives: positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95:1045–62. doi: 10.1037/a0013262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seligman MEP, Steen TA, Park N, Peterson C. Positive psychology progress: empirical validation of interventions. Am Psychol. 2005;60:410–21. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boehm J, Vie L, Kubzansky LD. The promise of well-being interventions for improving health risk behaviors. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2012;6:511–519. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1: Correlation Table of All Continuous Variables

Supplementary Table 2. Distribution of Life Satisfaction Scores Among All Categorical Variables

Supplementary Table 3: Association Between Life Satisfaction and Doctor Visits By Subgroup

Supplementary Table 4: Association Between Life Satisfaction and Doctor Visits By Chronic Disease Status