Abstract

Background

Hyperthyroidism increases heart rate, contractility and cardiac output, as well as metabolic rate. It is also accompanied by alterations in the regulation of cardiac substrate utilisation. Specifically, hyperthyroidism increases the ex vivo activity of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK), thereby inhibiting glucose oxidation via pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH). Cardiac hypertrophy is another effect of hyperthyroidism, with an increase in the abundance of mitochondria. Although the hypertrophy is initially beneficial, it can eventually lead to heart failure. The aim of this study was to use hyperpolarized magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) to investigate the rate and regulation of in vivo pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) flux in the hyperthyroid heart, and to establish whether modulation of flux through PDH would alter cardiac hypertrophy.

Methods & Results

Hyperthyroidism was induced in 18 male Wistar rats with 7 daily intraperitoneal injections of freshly prepared triiodothyronine (T3; 0.2 mg/kg/day). In vivo PDH flux, assessed using hyperpolarized MRS, was reduced by 59% in hyperthyroid animals (0.0022 ± 0.0002 s−1 vs 0.0055 ± 0.0005 s−1, P = 0.0003) and this reduction was completely reversed by both acute and chronic delivery of the PDK inhibitor, dichloroacetic acid (DCA). Hyperpolarized [2-13C]pyruvate was also used to evaluate Krebs cycle metabolism and demonstrated a unique marker of anaplerosis, the level of which was significantly increased in the hyperthyroid heart. Cine MRI showed that chronic DCA treatment significantly reduced the hypertrophy observed in hyperthyroid animals (100 ± 20 mg vs 200 ± 30 mg; P = 0.04) despite no change to the increase observed in cardiac output.

Conclusions

This work has demonstrated that inhibition of glucose oxidation in the hyperthyroid heart in vivo is PDK mediated. Relieving this inhibition can increase the metabolic flexibility of the hyperthyroid heart and reduce the level of hypertrophy that develops whilst maintaining the increased cardiac output required to meet the higher systemic metabolic demand.

Keywords: Hyperthyroidism, Hyperpolarized Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy, Pyruvate Dehydrogenase

Introduction

Thyroid hormones regulate many aspects of growth, development and energy metabolism, and are critical for normal cell function in multiple organs 1-3. The heart is particularly sensitive to the action of thyroid hormones, with thyroid dysfunction having detrimental effects on the cardiovascular system. Minimal alterations in circulating thyroid hormone concentrations significantly alter many cardiac parameters. For instance, an increase in circulating thyroid hormone markedly increases heart rate, contractility and cardiac output 4-7. Further, hyperthyroid patients often develop hypertrophy, tachycardia, palpitations, fatigue and atrial arrhythmias 8.

Hyperthyroidism is accompanied by alterations in the regulation of cardiac substrate utilisation. Specifically, hyperthyroidism increases the ex vivo activity of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK) 9, 10, thereby inhibiting glucose oxidation via pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH). PDH catalyses the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA, which can be used to generate ATP via the Krebs cycle 11, 12. To date it has not been possible to evaluate in vivo whether hyperthyroidism is associated with alterations in PDH flux and/or the mechanisms controlling in vivo PDH activity and regulation.

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), in conjunction with 13C-labelled substrates, has been used to study cardiac metabolism since the early 1980’s, however the inherently low sensitivity of this technique has largely limited its application to the study of steady state metabolism in perfused hearts. The recent development of hyperpolarized MRS has addressed this problem by improving signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) more than 10,000-fold 13. The increase in SNR has made it possible to visualise the uptake of 13C-labelled metabolites in vivo, as well as their metabolic conversion through specific enzymes in real time 13, 14.

The primary aim of this study was to use hyperpolarized 13C MRS to investigate the effects of hyperthyroidism on in vivo PDH flux following 7 days of chronically increased circulating thyroid hormone (triiodothyronine; T3) concentrations. Metabolic perturbations were further defined using hyperpolarized [2-13C]pyruvate to assess Krebs cycle metabolism 15 and ex vivo metabolomics to evaluate differences in glycolytic substrate/product concentrations 16, 17.

A secondary aim was to use hyperpolarized 13C MRS to better characterise the mechanism of in vivo PDH regulation in the hyperthyroid heart. Two distinct mechanisms exist by which PDH flux can be regulated. The end products of fatty acid oxidation, acetyl-CoA and NADH, can directly inhibit PDH reducing PDH flux18, 19. Alternatively, acetyl-CoA and NADH can allosterically activate PDK or, in the longer term, transcriptional effectors may increase the specific activity and/or expression of PDK, thus increasing PDH phosphorylation and reducing PDH flux 20-22. To confirm whether any PDH inhibition observed in the hyperthyroid heart was PDK mediated, the PDK inhibitor dichloroacetic acid (DCA) was infused prior to MRS analysis. DCA prevents PDK mediated inhibition of PDH without affecting direct regulatory contributions from end product inhibition on the PDH complex 23. Therefore, by assessing the effect of DCA on PDH flux, the involvement of PDK in the in vivo regulation of PDH could be confirmed.

Finally, to investigate the functional and metabolic consequences of PDH inhibition in the hyperthyroid heart, hyperpolarized MRS and cine MRI were used to assess hyperthyroid animals with and without DCA treatment throughout the 7 day T3 administration period. In this way, the effects specifically resulting from PDH inhibition could be defined and the functional and metabolic consequences of alleviating PDH inhibition in the hyperthyroid heart could be evaluated.

Methods

Animal Preparation

The study conformed to Home Office Guidance on the Operation of the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act (HMSO) of 1986 and to University of Oxford institutional guidelines. Eighteen male Wistar rats (~250 g) were housed on a 12:12-h light–dark cycle (lights on 7 am, off 7 pm) in facilities at the University of Oxford. All animal studies were performed between 8 am and 1 pm. Hyperthyroidism was induced with 7 daily intraperitoneal injections of freshly prepared triiodothyronine beginning on day 2 of the study (T3; 0.2 mg/kg/day).

At day 0 (prior to first T3 injection to enable use as control data) and day 8, PDH flux was determined using hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate 24. Krebs cycle metabolism was assessed on day 1 (also prior to first T3 injection) and day 9 using hyperpolarized [2-13C]pyruvate 15. One millilitre of the hyperpolarized tracer was injected i.v. over 10 s into the anesthetized rat and 60 individual cardiac spectra were acquired over 1 min. Cardiac 13C MR spectra were analysed using the AMARES algorithm as implemented in the jMRUI software package. The rate of exchange of the 13C label from the hyperpolarized pyruvate to each of its downstream metabolites was assessed using a kinetic model specifically designed for the assessment of hyperpolarized pyruvate metabolism 24, 25. The model accounts for many of the variables in the hyperpolarized experiment, including the rate of injection, the initial polarization level of the hyperpolarized pyruvate and the rate of decay of each of the hyperpolarized compounds. The MRS acquisition and analysis protocol is described fully in the Supplemental Material.

Acute Dichloroacetic Acid (DCA) Administration

One group of rats (n=6) received a 1 mL bolus of DCA via the tail vein (30 mg/mL in PBS, neutralised to pH 7.2 with concentrated NaOH), followed by a 0.5 mL infusion over 15 min immediately prior to infusion of hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate on day 8.

Dichloroacetic Acid (DCA) Treatment

One group of rats (n=5) were treated with DCA throughout the 7 day T3 administration period. Drinking water was replaced on day 2 (immediately post the first T3 injection) with water containing DCA (0.75 g/L, neutralised to pH 7.2 with NaOH). Water intake was monitored daily.

MRI Measurements of Cardiac Function

On day 1 and 8, post hyperpolarized MRS analysis, cardiac function in animals without DCA infusion/treatment (n=7), and animals treated with DCA for 7 days (n=5), was assessed using MRI, as described in the Supplemental Material. Briefly, cine-MR images, consisting of 28–35 frames per heart cycle, were acquired in ~7 contiguous slices in the short-axis orientation covering the entire heart (FOV = 51.2×51.2 mm, matrix size = 256×256, slice thickness = 1.5 mm, giving a voxel size of 0.015 mm3, TE/TR= 1.43 / 4.6 ms, 0.5 ms / 17.5° Gaussian RF excitation pulse and 4 averages. End-diastolic (ED) and end-systolic (ES) frames were selected as those with the largest and smallest cavity volumes, respectively. Epicardial and endocardial borders were outlined using the freehand drawing function of ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, USA). Measurements from all slices were summed to calculate ED volume (EDV), ES volume (ESV), stroke volume (SV = EDV-ESV), ejection fraction (EF= SV/EDV) and cardiac output (CO= SV×heart rate). LV mass was calculated as myocardial area × slice thickness × myocardial specific gravity (1.05) 26.

Plasma metabolite measurements

Immediately prior to examination with hyperpolarized pyruvate on days 0 and 8, ~500 μL of saphenous vein blood was sampled from anaesthetised rats. All blood samples were immediately centrifuged (3400 rpm; 10 min; 4°C) and plasma removed. A 50 μL aliquot of plasma was separated and 1 μL tetrahydrolipstatin THL (30 μg/mL) was added for non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA) analysis. All plasma samples were immediately frozen and stored at −80°C. An ABX Pentra 400 (Horiba ABX Diagnostics, USA) was used to perform plasma assays for glucose, NEFAs, triglycerides, lactate, cholesterol and β-hydroxybutyrate. Rats were euthanized by exsanguination following an overdose of isofluorane ~50 mins post MR analysis on day 9. Hearts were immediately excised, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for analysis of PDH activity and PDK4 protein expression.

Metabolomic analysis of cardiac metabolites

Another group of rats were administered 7 daily T3 injections as described above (n=6) or received 7 daily intraperitoneal injections of saline water (0.2 mL) to serve as controls (n=6). On day 7, rats were euthanized by exsanguination following an overdose of isoflurane and hearts were immediately excised, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. From control hearts, a section of tissue was taken for assessment of PDH activity and PDK4 protein expression. Metabolites were extracted from remaining heart tissue using methanol/chloroform/water and analysed using 1H-NMR spectroscopy as previously described 16. NMR spectra were processed using ACD SpecManager 1D NMR processor (version 8; ACD, Toronto, Canada; see Supplemental Material).

Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Activity Assay

The activity of the active and total fractions of PDH (PDHa and PDHt) were determined spectrophotometrically by the method of Seymour and Chatham27. Briefly, the assay required the preparation of cardiac tissue with one of two homogenisation buffers for either PDHa or PDHt measurement. PDHa was assessed when PDH was extracted under conditions where both PDP and PDK were inhibited by KH2PO4, KF, DCA and ADP. PDHt was assessed under conditions where PDH phosphatase (PDP) was stimulated by Mg2+ and PDK inhibited by DCA and ADP. The rate of NADH production over the first 30 s was used to determine activity in units of μmol/min/g wet weight.

Western Blotting

Protein levels of PDK4 were measured in total left ventricular homogenates using SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. All samples were run in duplicate on separate gels to confirm results. Protein levels were related to internal standards to ensure homogeneity between samples and gels.

Statistical Analysis

Values are reported as mean ± S.E.M. Statistical significance between the ‘Control’, ‘T3’, ‘T3 + Acute DCA Administration’ and ‘T3 + DCA Treatment’ groups for the in vivo hyperpolarized data, the in vitro metabolomics, the PDH activity assay, the plasma metabolite analysis and the Western blotting was assessed using a Kruskal-Wallis test followed by a Mann-Whitney test with a post-hoc Bonferroni correction28. For the CINE MRI data, interaction between the effects of T3 and DCA was assessed using repeated measures ANOVA. Statistical significance between parameters measured on day 0 and day 8 was assessed using a paired t-test. Statistical significance between ‘T3’ and ‘T3 + DCA Treatment’ groups was assessed using a two-sample t-test assuming equal variances. Statistical significance was considered at the P<0.05 level.

Results

Cardiac Metabolism in the Hyperthyroid Heart

Cardiac Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Flux

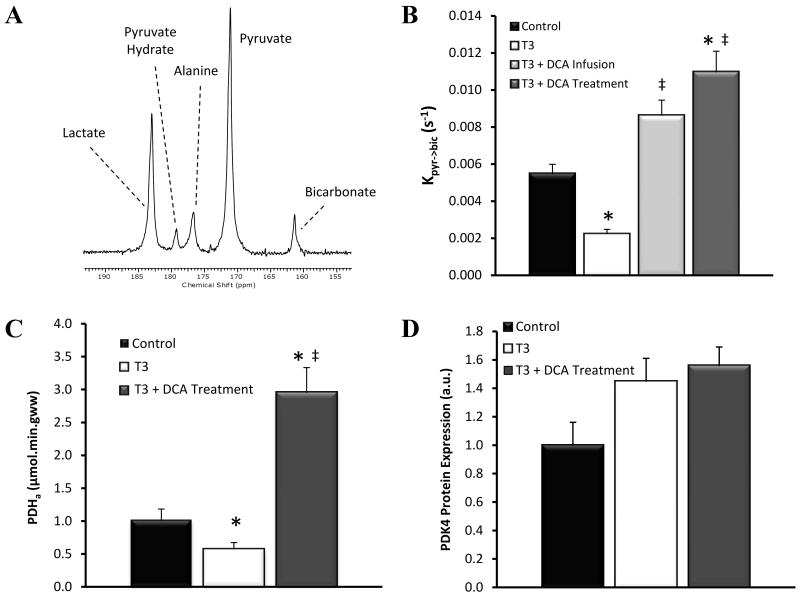

Using hyperpolarized 13C MRS, we measured [1-13C]pyruvate conversion into the metabolic product bicarbonate in real time (Fig. 1A). The exchange of 13C label from [1-13C]pyruvate into 13C-bicarbonate gave a direct assessment of metabolic flux through PDH 24. All data from day 0 were combined to form a single control dataset. Prior to any T3 administration, the rate of label exchange from [1-13C]pyruvate into 13C-bicarbonate in these animals was calculated to be 0.0055 ± 0.0005 s−1. After 7 days T3 administration (T3 group) PDH flux was significantly reduced by 59% to 0.0022 ± 0.0002 s−1 (P=0.0003; Fig. 1B). The reduction in PDH activity (PDHa) versus control PDHa, was confirmed using an ex vivo spectrophotometric approach which detected a 46% decrease versus control values (P=0.0084; Fig.1C).

Figure 1.

(A) Single representative MR cardiac spectrum of a control rat at day 0 following infusion of [1-13C]pyruvate, recorded at t = 10 s. Pyruvate (and its equilibrium product pyruvate hydrate), as well as lactate, alanine and bicarbonate, metabolic products of pyruvate, are annotated. (B) The rate of exchange of 13C label from [1-13C]pyruvate in to [1-13C]bicarbonate in each group assessed using hyperpolarized 13C-MRS. (C) The activity of the active PDH fraction (PDHa) assessed ex vivo using a spectrophotometric approach. (D) Relative expression of PDK4 as assessed by Western blotting. (Key: ‘Control’ - combined day 0 data (n=18); ‘T3’ - hyperthyroid rats (n=7); ‘T3 + DCA Infusion’ - received an acute infusion of DCA immediately prior to MRS analysis (n=6), ‘T3 + DCA Treatment’ received DCA treatment throughout the 7 day T3 administration period (n=5); * P < 0.05 vs. control, ‡ P < 0.05 vs. T3.).

Other Metabolic Abnormalities in the Hyperthyroid Heart

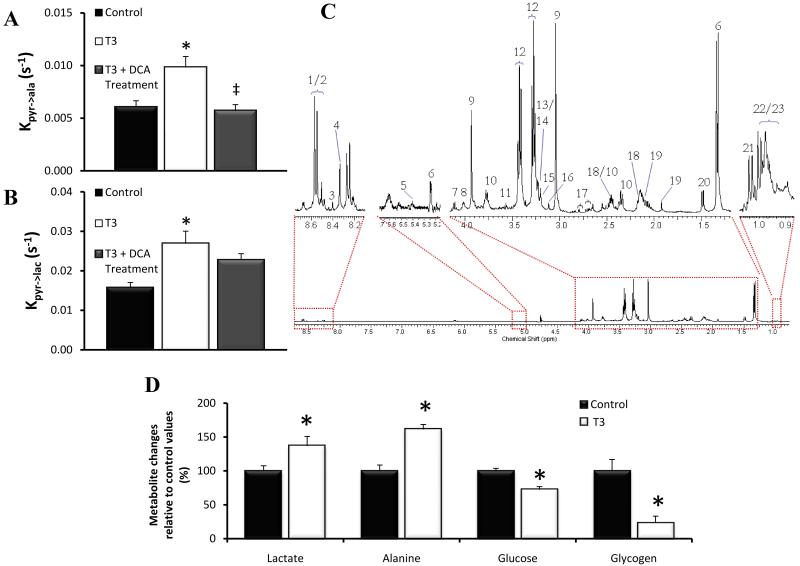

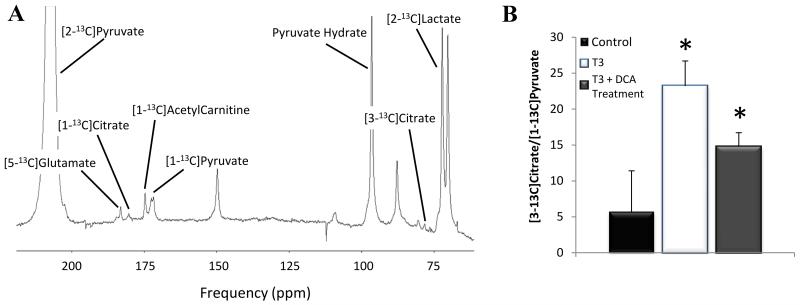

[1-13C]alanine and [1-13C]lactate appeared due to alanine aminotransferase (AAT) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) mediated 13C-label exchange, respectively. The measured exchange rate of 13C label from [1-13C]pyruvate into [1-13C]alanine, demonstrated a significant 62% increase in the T3 group relative to control animals (P=0.0048; Fig.2A). The rate of exchange of 13C label into [1-13C]lactate signal was also increased by 72% in hyperthyroid animals (P=0.0049; Fig.2B). Ex vivo 1H-NMR spectroscopy analysis of the cardiac tissue for hyperthyroid hearts revealed that myocardial concentrations of glucose and glycogen were decreased to 73 ± 7% (P=0.0043) and 24 ± 13% (P=0.0087) of control values, respectively. The concentration of the glycolytic products lactate and alanine were elevated to 137 ± 14% (P=0.026) and 162 ± 21% (P=0.0022) of the control values, respectively (Fig.2C). Hyperpolarized [2-13C]pyruvate, in conjunction with MRS, enabled Krebs cycle metabolism to be investigated. Exchange of 13C label into [1-13C]citrate, [5-13C]glutamate and [1-13C]acetylcarnitine was significantly reduced in the hyperthyroid hearts relative to controls (P<0.05, Table 1). This probably reflected a reduction in label reaching the Krebs cycle due to the decrease in PDH flux. To try and account for this, values were further normalised against PDH flux values. Following normalization, no significant difference was seen between the rates of 13C label incorporation into citrate, glutamate or acetylcarnitine between the control and hyperthyroid animals. Further evaluation of the data revealed a previously unobserved peak at ~ 78.1 ppm, which was evident in the hyperthyroid heart spectra but barely quantifiable in the control spectra (Fig.3A). Further work enabled identification of this peak as [3-13C]citrate, which would be formed through anaplerotic processing of [2-13C]pyruvate via oxaloacetate. Due to the relatively low amplitude of the [3-13C]citrate peak, summing 10 s of data (from t = 4 s) was necessary for quantification, but revealed levels to be increased more than 4-fold in the T3 group relative to controls (P = 0.004; Fig 3B).

Figure 2.

(A) The maximum [1-13C]alanine / maximum [1-13C]pyruvate ratio and (B) The maximum [1-13C]lactate / maximum [1-13C]pyruvate ratio in each group. (*P<0.05 vs. control, ‡P<0.05 vs. T3) (C) An example high-resolution 500 MHz 1H NMR spectrum of an extract of cardiac tissue. Peak 1: valine/leucine/isoleucine, peak 2: β-hydroxybutyrate, peak 3: lactate, peak 4: alanine, peak 5: acetate, peak 6: glutamate, peak 7: glutamate and glutamine, peak 8: glutamine, peak 9: succinate, peak 10: malate, peak 11: citrate, peak 12: aspartate, peak 13: creatine, peak 14: choline, peak 15: phosphocholine / glycerophosphocholine, peak 16: taurine, peak 17: glycine, peak 18: glucose, peak 19: glycerol backbone. (D) Metabolic perturbations in the hyperthyroid heart measured using ex vivo 1H-NMR spectroscopy. Changes are expressed as percentages of the measured control values and were all significant at the P<0.05 level.

Table 1. Rate of exchange of 13C label from [2-13C]pyruvate into [5-13C]Glutamate, [1-13C]Citrate and [1-13C]Acetylcarnitine following [2-13C]pyruvate infusion into control animals (n = 12), hyperthyroid animals (T3, n = 7) and hyperthyroid animals plus DCA treatment (T3 + DCA Treatment; n=5).

| Group | [5-13C]Glutamate (s−1) | [1-13C]Citrate (s−1) | [1-13C]Acetylcarnitine (s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.0017 ± 0.0002 | 0.0008 ± 0.0001 | 0.0060 ± 0.0008 |

| T3 | 0.0009 ± 0.0001 * | 0.00017 ± 0.00005 * | 0.0018 ± 0.0004 * |

| T3 + DCA Treatment | 0.0036 ± 0.0003 * ‡ | 0.0021 ± 0.0004 ‡ | 0.0093 ± 0.0008 ‡ |

| Normalised to [13C]bicarbonate/[1-13C]pyruvate (measure of PDH flux): | |||

| Control | 0.40 ± 0.06 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

| T3 | 0.42 ± 0.03 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.79 ± 0.08 |

| T3 + DCA Treatment | 0.34 ± 0.05 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 0.87 ± 0.09 |

P<0.05 vs. control,

P<0.05 vs. T3.

Figure 3.

(A) MR cardiac spectrum of a T3 rat at day 8 following infusion of [2-13C]pyruvate. Ten individual spectra were summed to generate this spectrum (t = 4-13 s). [2-13C]pyruvate and its metabolic products are annotated (unlabelled peaks are impurities in the [2-13C]pyruvate preparation). (B) The [3-13C]citrate/[2-13C]pyruvate ratio in each group assessed using hyperpolarized 13C-MRS. (Key: Control- combined day 0 data (n=12); T3-hyperthyroid rats (n=7); ‘T3 + DCA Treatment’ received DCA treatment throughout the 7 day T3 administration period (n=5); * P<0.05 vs. control).

Plasma metabolites

After 7 days of T3 administration there was a ~3-fold increase in the concentration of circulating free fatty acids with levels of ~ 2.1 mM (P=0.0008). The concentration of the ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate was significantly increased more than 4-fold in the hyperthyroid rats (P=0.0003). No significant differences in plasma concentrations of cholesterol, lactate or glucose were detected (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of plasma metabolite concentrations in control rats (n = 12), hyperthyroid rats (T3; n = 7), and hyperthyroid rats treated with DCA for 7 days (T3 + DCA Treatment; n=5).

| Metabolite | Control | T3 | T3 + DCA Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Free fatty acids (mmol L−1) | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.3 * | 1.3 ± 0.2 |

| Glucose (mmol L−1) | 10.0 ± 0.4 | 8.9 ± 0.4 | 8.2 ± 0.2 * |

| Lactate (mmol L−1) | 1.33 ± 0.09 | 1.29 ± 0.06 | 0.64 ± 0.04 *‡ |

| β-hydroxybutyrate (mmol L−1) | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.49 ± 0.08 * | 1.0 ± 0.2 * |

| Cholesterol (mmol L−1) | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 * |

| Triacylglycerides (mmol L−1) | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.11 ± 0.09 | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

P < 0.05 vs. control,

P < 0.05 vs. T3.

PDH Regulation in the Hyperthyroid Heart

To study the predominant mechanism of PDH regulation in the hyperthyroid heart, hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate metabolism was analysed in hyperthyroid rats following the administration of DCA immediately prior to hyperpolarized MRS analysis. Infusion of DCA caused a 3.9-fold increase in PDH flux relative to flux in hyperthyroid hearts (P=0.0012) (Fig.1B) and a 1.6-fold increase in PDH flux over control values (P=0.0084). Figure 1D shows the expression of PDK4 protein as assessed by Western blotting, (Control = 1.0±0.3, T3 = 1.5±0.3, p=0.06).

DCA Treatment

To establish whether relieving the PDK mediated inhibition of PDH would have any effect on the hyperthyroid heart, the functional and metabolic effects of DCA treatment throughout the 7 day T3 administration period were assessed. A combined hyperpolarized MRS and cine MRI approach was used. The results of this study are summarised in Figures 1-4 and Tables 1-3. DCA treatment increased PDH flux by 4.9-fold relative to levels in hyperthyroid animals (P=0.0025) and by 2.0-fold relative to controls (P=0.0017), which is similar in magnitude with the 1.6-fold increase observed in animals following an acute DCA infusion. To verify these findings, a spectrophotometric assay was used to measure PDH activity (PDHa) ex vivo. This confirmed that PDHa was increased 4.4-fold in DCA treated animals relative to T3 animals without DCA treatment (P=0.0027; Fig.1C). Figure 1D shows the expression of PDK4 protein as assessed by Western blotting, (T3 + DCA vs Control = 1.6±0.3 vs 1.0±0.3, P=0.06, T3 + DCA vs T3 = 1.6±0.3 vs 1.5±0.3, P=0.69).

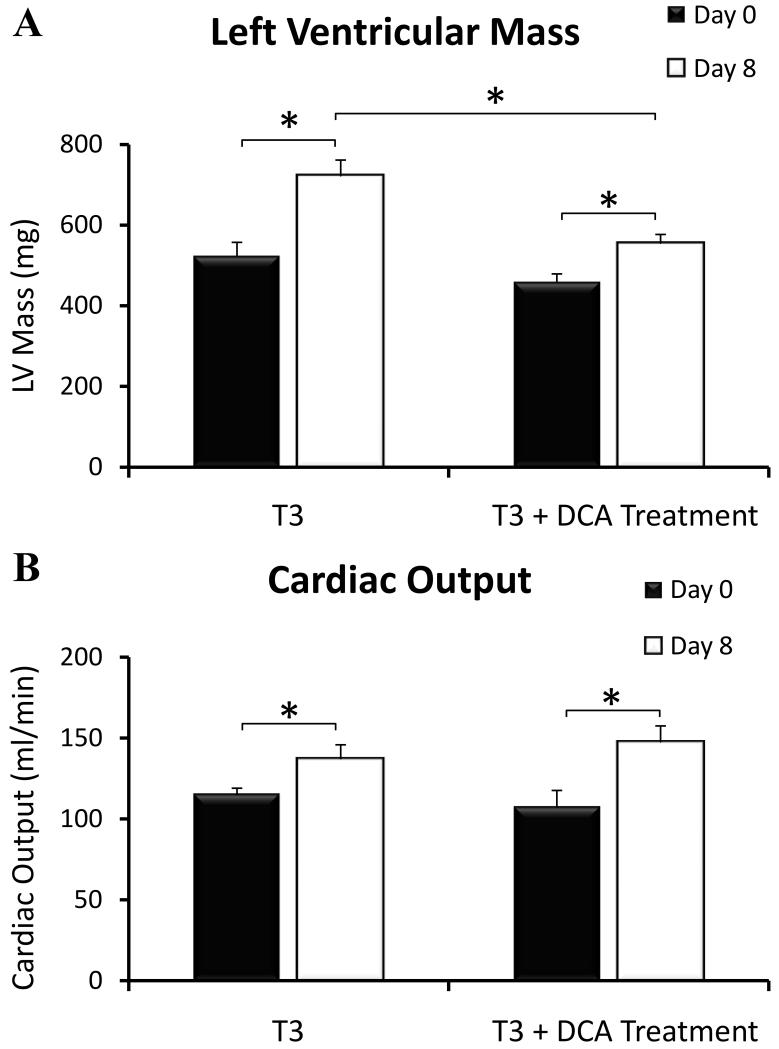

Figure 4.

Cardiac mass and cardiac function (cardiac output) assessed using MRI, in the hyperthyroid rat heart with and without DCA treatment at Day 0 (Black) and Day 8 (White) (*P<0.05).

Table 3. Cine MRI measurements of cardiac morphology and function in hyperthyroid rats (T3, n=7), and hyperthyroid rats treated with DCA for 7 days (T3 + DCA Treatment; n=5). Day 0 control data was collected prior to the first injection of T3. The interaction between T3 and DCA was assessed using a repeated measures ANOVA. Statistical significance between day 0 and day 8 data was assessed using a paired Student’s t-test. Statistical significance between T3 and T3 + DCA Treatment groups was assessed using an unpaired t-test.

| Group | T3 | T3 + DCA Treatment | Interaction Between T3 & DCA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Day 0 | Day 8 | Day 0 | Day 8 | ||

| Average LVmass (mg) | 520 ± 30 | 720 ± 40 † | 460 ± 20 | 560 ± 20 †‡ | p = 0.042 |

| End Diastolic Lumen Volume (μl) | 350 ± 20 | 300 ± 20 † | 280 ± 20 | 290 ± 20 | p = 0.048 |

| End Systolic Lumen Volume (μl) | 58 ± 6 | 46 ± 7 | 42 ± 7 | 26 ± 3 †‡ | p = n.s. |

| Stroke Volume (μl) | 290 ± 20 | 260 ± 20 † | 240 ± 20 | 260 ± 20 | p = 0.019 |

| Ejection Fraction (%) | 84 ± 1 | 85 ± 2 | 85 ± 2 | 91 ± 1 † ‡ | p = n.s. |

| Heart Rate (bpm) | 400 ± 30 | 530 ± 20 † | 450 ± 10 | 562 ± 7 † | p = n.s. |

| Cardiac Output (ml/min) | 115 ± 4 | 137 ± 9 † | 110 ± 10 | 150 ± 10 † | p = n.s. |

| HW:BW (*10−3) | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.1 † | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.1 †‡ | p = n.s. |

P<0.05 vs. day 0,

P<0.05 vs. T3.

The rate of 13C label incorporation into [1-13C]alanine was 42% lower than levels measured in hyperthyroid animals without DCA treatment (P = 0.0056) and the same as control values (Fig.2A). Incorporation of 13C label into [1-13C]lactate was not statistically different from control levels or levels in untreated hyperthyroid animals (Fig. 2B). Label incorporation into [1-13C]citrate, [5-13C]glutamate and [1-13C]acetylcarnitine at day 7 was significantly faster than in untreated hyperthyroid animals (P<0.01), however, when values were normalised to PDH flux to account for the increase in 13C-label entering the Krebs cycle, no significant differences were seen (Table 1). The amount of [3-13C]citrate in treated animals at day 7 was more than 3-fold higher than control levels (P=0.01; Fig.3B). Analysis of circulating metabolite concentrations in plasma revealed increased β-hydroxybutyrate relative to control animals, whilst lactate, glucose and cholesterol levels were decreased relative to controls (P<0.05). DCA treatment also reduced circulating free fatty acid levels back to control levels (Table 2).

The LV mass and the heart weight:body weight (HW:BW) were significantly higher in all animals, relative to day 0 (P<0.05, Table 3), indicating the development of hypertrophy in both untreated and DCA treated animals. However, the average increase in LV mass was significantly lower in the treated hyperthyroid animals (100 ± 20 mg) versus the untreated hyperthyroid animals (200 ± 30 mg; P = 0.04, Fig.4). Cardiac output was increased in all animals versus control (P<0.05), but no significant difference was detected between treated and untreated animals (Table 3 and Fig.4).

Discussion

In this study, we used hyperpolarized MRS to non-invasively measure the real time conversion of [1-13C]pyruvate into [13C]bicarbonate in order to assess in vivo PDH flux in the hyperthyroid rat heart. We have, for the first time, demonstrated that cardiac PDH flux was decreased by 59% in vivo following 1 week of chronically elevated T3 levels. Reduced PDH flux would severely diminish the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA thereby reducing the contribution of glucose oxidation to energy generation. The exact mechanism by which T3 reduces PDH flux is yet to be fully elucidated. There is evidence to suggest that T3 directly stimulates PDK4 gene expression via two thyroid response elements (TREs) in the PDK4 promoter 29. Conversely, other studies have shown that the reduction in PDH flux occurs subsequent to an increase in fatty acid oxidation 30, 31. In support of the latter hypothesis, analysis of circulating plasma metabolite levels from rats administered T3 revealed an increase in the concentration of fatty acids and β-hydroxybutyrate relative to control levels. Our results are also consistent with the findings of Sugden et al. who observed a decrease in the ratio of cardiac free to acylated carnitines, indicating increased myocardial fatty acid oxidation 32 and many other studies that have demonstrated an increase in the circulating levels of fatty acids and their subsequent oxidation in hyperthyroidism33-35. The increase in circulating fatty acids is likely to be secondary to an increase in lipolysis in the white adipose tissue which is known to be, in part, regulated by thyroid hormone36.

We also found evidence of upregulation of several important energy generating metabolic pathways. The ex vivo metabolomic experiments provided evidence of increased cardiac glucose utilisation in rats treated with T3, despite the reduction in PDH flux. In line with this, increased [1-13C]lactate and [1-13C]alanine were detected in hyperthyroid hearts. In a previous study, non-oxidative glucose metabolism and glycogenolysis were observed to increase with hyperthyroidism 37. The authors suggest that this was caused by a perturbation in energy metabolism, leading to increased levels of inorganic phosphate, which would stimulate glycogen metabolism.

We also found evidence of increased anaplerotic processing of pyruvate, a mechanism by which carbon flux into the Krebs cycle can be maintained under conditions of reduced PDH flux. We have been able to identify and quantify a MRS resonance corresponding to [3-13C]citrate, the formation of which has not previously been observed in vivo, in real time. Previous studies investigating substrate utilisation in the hypertrophied heart have shown that reduced PDH flux is compensated for by an increase in pyruvate carboxylation via malic enzyme 38. The expression of pyruvate carboxylase is also known to be increased by T3 39. Therefore, it is plausible that in the hyperthyroid heart, pyruvate generated by increased glucose metabolism is metabolised anaplerotically to increase carbon flux into the Krebs cycle and maintain energy generation under conditions of low PDH flux. The ability to quantify in vivo [3-13C]citrate in this study, provided the first example of how hyperpolarized MRS can be used for the non-invasive assessment of anaplerosis, which will undoubtedly prove useful in future studies of cardiac disease.

PDH Regulation

One interesting and potentially useful application of hyperpolarized MRS is the ability to probe mechanisms of metabolic regulation in vivo. For a number of reasons, existing in vitro and ex vivo analyses used for studying metabolic regulation are flawed, making translation of the acquired results into in vivo models problematic. For example, many assays fail to consider how metabolite composition in vivo may affect enzyme activity through processes such as substrate or end product inhibition. These are of particular importance when studying the effects of disorders known to perturb metabolism in vivo such as hyperthyroidism. By selectively modulating a known regulatory pathway and using hyperpolarized MRS to assess subsequent changes in metabolic flux, novel information regarding metabolic regulation in disease can be obtained. In this study, hyperthyroid rats were infused with the PDK inhibitor DCA immediately prior to analysis by hyperpolarized MRS. In these rats, the T3-mediated decrease in PDH flux was completely reversed. As previous work has shown that DCA inhibits PDH in the presence of inhibitory concentrations of acetyl-CoA and NADH 40, this result confirms that the observed reduction in PDH flux is mediated by PDK, and that there is no discernable contribution from end product inhibition. This supports the findings of Sugden et al and Holness et al who both observed an increase in PDK4 expression in hyperthyroid hearts 41, 42. Although in our study the increase in PDK4 protein levels just failed to reach significance, this could be explained by the lower daily doses of T3 administered (0.2 mg/kg/day versus 1.0 mg/kg/day) or by the fact the hearts in our study were collected over 24 hours after the final T3 injection.

Effects of DCA Treatment on the Hyperthyroid Heart

The hyperthyroid heart undergoes well characterised functional and morphological changes, in that heart rate, contractility and cardiac output all increase, and cardiac hypertrophy is frequently observed. To determine whether the inhibition of PDH, which results in the inability to efficiently utilise glucose as a substrate for ATP synthesis, is a contributing factor in the development of T3 mediated hypertrophy, we treated a group of hyperthyroid rats with DCA throughout the 7 day T3 administration period. Consistent with the role of DCA, we observed a significant increase in PDH flux, a reduction in circulating glucose levels, and a reduction in 13C-label exchange with alanine, suggesting the intracellular alanine pool size was reduced. Interestingly, despite the 4.9-fold increase in PDH flux with DCA treatment versus untreated levels, no difference in PDK4 protein level was observed thereby confirming that chronic DCA administration only affects the activity, and not the expression of this enzyme.

Further analysis of circulating metabolite levels revealed a normalisation of circulating fatty acid concentrations and a reduction in glucose and cholesterol levels. These findings are consistent with a reduction in fatty acid oxidation, increased glucose oxidation and decreased lipolysis in DCA treated animals. Plasma lactate concentrations were also reduced, consistent with an increased level of lactate oxidation43 following DCA administration. The levels of β-hydroxybutyrate, which were elevated in the T3 animals relative to controls, were further increased in the DCA treated animals. This may be due to increased ketogenesis in the liver due to excess acetyl-CoA being generated from the significantly increased PDH flux, demonstrating the systemic effects that DCA treatment will have had on these animals.

Perhaps the most important alteration observed in the DCA treated hearts was a 52% decrease in cardiac hypertrophy. In the hyperthyroid heart, increases in myocyte diameter and abundance of mitochondria are well established44. Such morphological changes allow increased energy generation via enhanced fatty acid oxidation, thus enabling the heart to meet the increase in workload. By allowing the hyperthyroid heart to utilise both fatty acids and carbohydrates as a fuel source, DCA treatment could increase mitochondrial flexibility, thereby reducing the requirement for increased abundance of mitochondria. Consistent with this, T3-mediated cardiac hypertrophy was reduced in animals treated with DCA. However, the hyperthyroid heart must still respond to the increase in workload and increase cardiac output to ensure efficient systemic O2 delivery. This study therefore has demonstrated that by increasing the metabolic flexibility of the hyperthyroid heart, the response to increased levels of thyroid hormone is altered and cardiac hypertrophy is reduced. The side effects associated with DCA treatment, pain, numbness, and peripheral neuropathy 45, 46, prevent DCA being a viable treatment for hyperthyroidism, however our data suggest that alternative metabolic interventions may relieve some of the more serious symptoms associated with this disease and therefore warrant further investigation.

Further Comments

The hyperpolarized [1-13C] and [2-13C]pyruvate experiments described in this work produced spectra that were localized to the heart with a surface coil placed over the chest. It is certain that a small amount of contamination from neighbouring organs, notably blood, liver and skeletal muscle, made some contribution to the measured signals, especially in the detection of [1-13C]lactate and [1-13C]alanine. However, we are confident that the observation of metabolites downstream of PDH were dominated specifically by cardiac metabolism, based both on the metabolic time course of metabolite appearance and the high metabolic turnover of the heart. The time course of metabolite production closely followed the time course of injected pyruvate in that the initial detection and accumulation of bicarbonate, citrate and acetylcarnitine occurred within 1-3 s of pyruvate arrival in the chest. It seems unlikely that metabolites produced anywhere outside the heart would appear so rapidly after cardiac pyruvate delivery. Further, the extremely high rate of PDH and Krebs cycle flux in the heart47 compared with liver 48, 49 and resting skeletal muscle 50, 51 provide further evidence that the bicarbonate measurements in this study reflected local cardiac metabolism.

The potential to study the metabolic effects of hyperthyroidism, and other cardiovascular diseases, in humans using the hyperpolarized techniques presented here is clear. The first trials in man using hyperpolarized pyruvate as a metabolic biomarker are imminent and offer many advantages over other forms of metabolic assessment, i.e. no radiation exposure, minimally invasive procedure etc. Metabolic studies using this technology can be integrated into existing MRI assessments of cardiac structure and function, as demonstrated here with a combined CINE-MRI and hyperpolarized MRS assessment.

Supplementary Material

Summary.

The ability to non-invasively visualise real time metabolism has, for the first time revealed that a significant PDK mediated reduction in PDH flux in vivo contributes to the pathology of the hyperthyroid heart. This has been shown to be accompanied by increased glycolytic metabolism and anaplerotic flux into the Krebs cycle. Increasing the number of metabolic substrates available to the hyperthyroid heart significantly reduced hypertrophy, whilst maintaining an elevated cardiac output. Future work will focus on alternative metabolic interventions, which, like DCA, may alleviate the more serious effects of hyperthyroidism and slow progression of the cardiac effects of this disease.

Acknowledgements

We thank Emma Carter for her technical assistance.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by Medical Research Council Grant G0601490, British Heart Foundation Grant PG/07/070/23365, and GE Healthcare in the form of a prototype hyperpolarizer system and initial grant support.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Harrigan GG, LaPlante RH, Cosma GN, Cockerell G, Goodacre R, Maddox JF, Luyendyk JP, Ganey PE, Roth RA. Application of high-throughput fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy in toxicology studies: Contribution to a study on the development of an animal model for idiosyncratic toxicity. Toxicol Lett. 2004;146:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sussman MA. When the thyroid speaks, the heart listens. Circulation research. 2001;89:557–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dillmann WH. Cellular action of thyroid hormone on the heart. Thyroid. 2002;12:447–452. doi: 10.1089/105072502760143809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keogh JM, Matthews PM, Seymour AM, Radda GK. A phosphorus-31 nuclear magnetic resonance study of effects of altered thyroid state on cardiac bioenergetics. Advances in myocardiology. 1985;6:299–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buccino RA, Spann JF, Jr., Pool PE, Sonnenblick EH, Braunwald E. Influence of the thyroid state on the intrinsic contractile properties and energy stores of the myocardium. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1967;46:1669–1682. doi: 10.1172/JCI105658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morkin E. Stimulation of cardiac myosin adenosine triphosphatase in thyrotoxicosis. Circulation research. 1979;44:1–7. doi: 10.1161/01.res.44.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siehl D, Chua BH, Lautensack-Belser N, Morgan HE. Faster protein and ribosome synthesis in thyroxine-induced hypertrophy of rat heart. The American journal of physiology. 1985;248:C309–319. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1985.248.3.C309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duggal J, Singh S, Barsano CP, Arora R. Cardiovascular risk with subclinical hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism: Pathophysiology and management. J Cardiometab Syndr. 2007;2:198–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-4564.2007.06583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orfali KA, Fryer LG, Holness MJ, Sugden MC. Interactive effects of insulin and triiodothyronine on pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase activity in cardiac myocytes. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 1995;27:901–908. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(95)90040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Priestman DA, Donald E, Holness MJ, Sugden MC. Different mechanisms underlie the long-term regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (pdhk) by tri-iodothyronine in heart and liver. FEBS letters. 1997;419:55–57. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Randle PJ. Fuel selection in animals. Biochemical Society transactions. 1986;14:799–806. doi: 10.1042/bst0140799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel MS, Roche TE. Molecular biology and biochemistry of pyruvate dehydrogenase complexes. Faseb J. 1990;4:3224–3233. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.4.14.2227213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Fridlund B, Gram A, Hansson G, Hansson L, Lerche MH, Servin R, Thaning M, Golman K. Increase in signal-to-noise ratio of > 10,000 times in liquid-state nmr. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10158–10163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1733835100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stowe KA, Burgess SC, Merritt M, Sherry AD, Malloy CR. Storage and oxidation of long-chain fatty acids in the c57/bl6 mouse heart as measured by nmr spectroscopy. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:4282–4287. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schroeder MA, Atherton HJ, Ball DR, Cole MA, Heather LC, Griffin JL, Clarke K, Radda GK, Tyler DJ. Real-time assessment of krebs cycle metabolism using hyperpolarized 13c magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Faseb J. 2009;23:2529–2538. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-129171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atherton HJ, Bailey NJ, Zhang W, Taylor J, Major H, Shockcor J, Clarke K, Griffin JL. A combined 1h-nmr spectroscopy- and mass spectrometry-based metabolomic study of the ppar-alpha null mutant mouse defines profound systemic changes in metabolism linked to the metabolic syndrome. Physiological genomics. 2006;27:178–186. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00060.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salek RM, Maguire ML, Bentley E, Rubtsov DV, Hough T, Cheeseman M, Nunez D, Sweatman BC, Haselden JN, Cox RD, Connor SC, Griffin JL. A metabolomic comparison of urinary changes in type 2 diabetes in mouse, rat, and human. Physiol Genomics. 2007;29:99–108. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00194.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper RH, Randle PJ, Denton RM. Stimulation of phosphorylation and inactivation of pyruvate dehydrogenase by physiological inhibitors of the pyruvate dehydrogenase reaction. Nature. 1975;257:808–809. doi: 10.1038/257808a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerbey AL, Randle PJ, Cooper RH, Whitehouse S, Pask HT, Denton RM. Regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase in rat heart. Mechanism of regulation of proportions of dephosphorylated and phosphorylated enzyme by oxidation of fatty acids and ketone bodies and of effects of diabetes: Role of coenzyme a, acetyl-coenzyme a and reduced and oxidized nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide. The Biochemical journal. 1976;154:327–348. doi: 10.1042/bj1540327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowker-Kinley MM, Davis WI, Wu P, Harris RA, Popov KM. Evidence for existence of tissue-specific regulation of the mammalian pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. The Biochemical journal. 1998;329(Pt 1):191–196. doi: 10.1042/bj3290191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugden MC, Bulmer K, Holness MJ. Fuel-sensing mechanisms integrating lipid and carbohydrate utilization. Biochemical Society transactions. 2001;29:272–278. doi: 10.1042/0300-5127:0290272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orfali KA, Fryer LG, Holness MJ, Sugden MC. Long-term regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase by high-fat feeding. Experiments in vivo and in cultured cardiomyocytes. FEBS letters. 1993;336:501–505. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80864-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whitehouse S, Randle PJ. Activation of pyruvate dehydrogenase in perfused rat heart by dichloroacetate (short communication) The Biochemical journal. 1973;134:651–653. doi: 10.1042/bj1340651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atherton HJ, Schroeder MA, Dodd MS, Heather LC, Carter EE, Cochlin LE, Nagel S, Sibson NR, Radda GK, Clarke K, Tyler DJ. Validation of the in vivo assessment of pyruvate dehydrogenase activity using hyperpolarized 13c-magnetic resonance spectroscopy. NMR Biomed. 2010 doi: 10.1002/nbm.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zierhut ML, Yen YF, Chen AP, Bok R, Albers MJ, Zhang V, Tropp J, Park I, Vigneron DB, Kurhanewicz J, Hurd RE, Nelson SJ. Kinetic modeling of hyperpolarized 13c1-pyruvate metabolism in normal rats and tramp mice. J Magn Reson. 2010;202:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tyler DJ, Lygate CA, Schneider JE, Cassidy PJ, Neubauer S, Clarke K. Cine-mr imaging of the normal and infarcted rat heart using an 11.7 t vertical bore mr system. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2006;8:327–333. doi: 10.1080/10976640500451903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seymour AM, Chatham JC. The effects of hypertrophy and diabetes on cardiac pyruvate dehydrogenase activity. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 1997;29:2771–2778. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glantz SA. Primer of biostatistics. McGraw-Hill Medical Pub.; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Attia RR, Connnaughton S, Boone LR, Wang F, Elam MB, Ness GC, Cook GA, Park EA. Regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (pdk4) by thyroid hormone: Role of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator (pgc-1 alpha) J Biol Chem. 285:2375–2385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.039081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sugden MC, Priestman DA, Orfali KA, Holness MJ. Hyperthyroidism facilitates cardiac fatty acid oxidation through altered regulation of cardiac carnitine palmitoyltransferase: Studies in vivo and with cardiac myocytes. Hormone and metabolic research. Hormon- und Stoffwechselforschung. 1999;31:300–306. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-978741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sugden MC, Liu YL, Holness MJ. Glucose utilization by skeletal muscles in vivo in experimental hyperthyroidism in the rat. The Biochemical journal. 1990;271:421–425. doi: 10.1042/bj2710421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sugden MC, Holness MJ, Liu YL, Smith DM, Fryer LG, Kruszynska YT. Mechanisms regulating cardiac fuel selection in hyperthyroidism. The Biochemical journal. 1992;286(Pt 2):513–517. doi: 10.1042/bj2860513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heather LC, Cole MA, Atherton HJ, Coumans WA, Evans RD, Tyler DJ, Glatz JF, Luiken JJ, Clarke K. Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase activation, substrate transporter translocation, and metabolism in the contracting hyperthyroid rat heart. Endocrinology. 2010;151:422–431. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mitrou P, Raptis SA, Dimitriadis G. Insulin action in hyperthyroidism: A focus on muscle and adipose tissue. Endocr Rev. 2010;31:663–679. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riis AL, Gravholt CH, Djurhuus CB, Norrelund H, Jorgensen JO, Weeke J, Moller N. Elevated regional lipolysis in hyperthyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4747–4753. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu YY, Heymann RS, Moatamed F, Schultz JJ, Sobel D, Brent GA. A mutant thyroid hormone receptor alpha antagonizes peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha signaling in vivo and impairs fatty acid oxidation. Endocrinology. 2007;148:1206–1217. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sauer MJ, Samuels TP, Howells LG, Seymour MA, Nedderman A, Houghton E, Bellworthy SJ, Anderson S, Coldham NG. Residues and metabolism of 19-nortestosterone laurate in steers. Analyst. 1998;123:2653–2660. doi: 10.1039/a805617j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pound KM, Sorokina N, Ballal K, Berkich DA, Fasano M, Lanoue KF, Taegtmeyer H, O’Donnell JM, Lewandowski ED. Substrate-enzyme competition attenuates upregulated anaplerotic flux through malic enzyme in hypertrophied rat heart and restores triacylglyceride content: Attenuating upregulated anaplerosis in hypertrophy. Circulation research. 2009;104:805–812. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.189951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weinberg MB, Utter MF. Effect of thyroid hormone on the turnover of rat liver pyruvate carboxylase and pyruvate dehydrogenase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1979;254:9492–9499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whitehouse S, Cooper RH, Randle PJ. Mechanism of activation of pyruvate dehydrogenase by dichloroacetate and other halogenated carboxylic acids. The Biochemical journal. 1974;141:761–774. doi: 10.1042/bj1410761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugden MC, Langdown ML, Harris RA, Holness MJ. Expression and regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase isoforms in the developing rat heart and in adulthood: Role of thyroid hormone status and lipid supply. The Biochemical journal. 2000;352(Pt 3):731–738. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holness MJ, Smith ND, Bulmer K, Hopkins T, Gibbons GF, Sugden MC. Evaluation of the role of peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor alpha in the regulation of cardiac pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 protein expression in response to starvation, high-fat feeding and hyperthyroidism. Biochem J. 2002;364:687–694. doi: 10.1042/BJ20011841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clark AS, Mitch WE, Goodman MN, Fagan JM, Goheer MA, Curnow RT. Dichloroacetate inhibits glycolysis and augments insulin-stimulated glycogen synthesis in rat muscle. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1987;79:588–594. doi: 10.1172/JCI112851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kubota N, Terauchi Y, Miki H, Tamemoto H, Yamauchi T, Komeda K, Satoh S, Nakano R, Ishii C, Sugiyama T, Eto K, Tsubamoto Y, Okuno A, Murakami K, Sekihara H, Hasegawa G, Naito M, Toyoshima Y, Tanaka S, Shiota K, Kitamura T, Fujita T, Ezaki O, Aizawa S, Kadowaki T, et al. Ppar gamma mediates high-fat diet-induced adipocyte hypertrophy and insulin resistance. Mol Cell. 1999;4:597–609. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Calcutt NA, Lopez VL, Bautista AD, Mizisin LM, Torres BR, Shroads AL, Mizisin AP, Stacpoole PW. Peripheral neuropathy in rats exposed to dichloroacetate. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 2009;68:985–993. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181b40217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spruijt L, Naviaux RK, McGowan KA, Nyhan WL, Sheean G, Haas RH, Barshop BA. Nerve conduction changes in patients with mitochondrial diseases treated with dichloroacetate. Muscle & nerve. 2001;24:916–924. doi: 10.1002/mus.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Merritt ME, Harrison C, Storey C, Jeffrey FM, Sherry AD, Malloy CR. Hyperpolarized 13c allows a direct measure of flux through a single enzyme-catalyzed step by nmr. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19773–19777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706235104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones JG, Solomon MA, Cole SM, Sherry AD, Malloy CR. An integrated (2)h and (13)c nmr study of gluconeogenesis and tca cycle flux in humans. American journal of physiology. 2001;281:E848–856. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.4.E848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jucker BM, Lee JY, Shulman RG. In vivo 13c nmr measurements of hepatocellular tricarboxylic acid cycle flux. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273:12187–12194. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gibala MJ, MacLean DA, Graham TE, Saltin B. Tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediate pool size and estimated cycle flux in human muscle during exercise. The American journal of physiology. 1998;275:E235–242. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.275.2.E235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jucker BM, Rennings AJ, Cline GW, Petersen KF, Shulman GI. In vivo nmr investigation of intramuscular glucose metabolism in conscious rats. The American journal of physiology. 1997;273:E139–148. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.273.1.E139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.