Abstract

Within the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus, circadian timekeeping and resetting have been shown to be largely dependent on both membrane depolarization and intracellular second-messenger signaling. In both of these processes, voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) mediate voltage-dependent calcium influx, which propagates neural impulses by stimulating vesicle fusion and instigates intracellular pathways resulting in clock gene expression. Through the cumulative actions of these processes the phase of the internal clock is modified to match the light cycle of the external environment. To parse out the distinct roles of the L-type VGCC, we analyzed mice deficient in Cav1.2 (Cacna1c) in brain tissue. We found that mice deficient in the Cav1.2 channel exhibited a significant reduction in their ability to phase-advance circadian behavior when subjected to a light pulse in the late night. Furthermore, the study revealed that the expression of Cav1.2 mRNA was rhythmic (peaking during the late night) and was regulated by the circadian clock component REV-ERBα. Finally, induction of clock genes in the early and late subjective night were each affected by the loss of Cav1.2, with reductions in Per2 and Per1 in the early and late night, respectively. In sum, these results reveal a role of the L-type VGCC Cav1.2 in mediating both clock gene expression and phase advances in response to a light pulse in the late night.

Introduction

Seated in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus, internalized rhythms of the external light-day cycle oscillate in the form of transcriptional/posttranslational autoregulatory feedback loops (Asher and Schibler, 2011). Information regarding light intensity is transduced from the intrinsically photoreceptive ganglion cells of the retina and travels along the retinohypothalamic tract, to ultimately influence clock phase in the SCN. Upon reaching the SCN, a diverse set of extracellular signals (e.g. glutamate, BDNF, VIP) are responsible for rapidly coordinating individual cellular clocks within the SCN by evoking chromatin remodeling and inducing immediate-early gene and clock gene expression. The product of these various cascades manifests in the shifting of the circadian clock to match the external phase with the internal phase (Golombek and Rosenstein, 2010). Therefore, both rapid propagation of neural activity and the combined influence of intracellular pathways are necessary to ensure prompt photic entrainment.

Integral in both of these signaling cascades, the role of calcium is ubiquitous throughout circadian and phase-shifting biology (Colwell, 2000; Pennartz et al., 2002). Extracellular calcium is required for proper clock gene expression (Lundkvist et al., 2005), while circadian calcium fluxes (independent of membrane depolarization) in the cytosol of SCN neurons have been demonstrated in vitro (Fukushima et al., 1997; Ikeda et al., 2003; Brancaccio et al., 2013) and change rapidly in response to the photic signals from the retina (Irwin and Allen, 2007). Additional work indicated that the amplitudes of these fluxes are largely influenced by membrane depolarization and, therefore, have been suggested to require a form of reinforcement or cross talk between SCN neurons in their regulation (Enoki et al., 2012). Taking the unique roles of calcium rhythmicity and dependence on membrane depolarization, voltage-gated calcium channels may play distinct roles in both processes.

In order for light to shift the molecular clock at the chromatin level, neuronal calcium influx via NMDA receptors and voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) is responsible for activating second-messenger signaling systems. Ultimately the second messengers converge in CREB-mediated transcription of the immediate early-gene c-fos and the clock genes Per1 and Per2 (West et al., 2001; Kornhauser et al., 2002). Through this mechanism, exposure to light directly affects the phase of the molecular clock. Despite the simplicity of this model, the circadian clock appears to regulate its own input pathway as shifting the phase of the molecular clock is dependent on both the time of night at which light is received and on phase-specific molecular mechanisms. Ding et al., 1998 illustrated this point by demonstrating a time-of-night specific role of the ryanodine receptors in the SCN; with ryanodine receptors releasing intracellular calcium in the early subjective night to mediate phase delays but playing no role in phase advances induced in the late subjective night. Furthermore, mice deficient for the gene coding for calbindin D-28k (a cytosolic calcium buffering and sensing protein) display increased phase delays when subjected to light in the early night, further supporting differential pathways of calcium signaling in the adaptation of the molecular clock to light (Stadler et al., 2010).

Due to the extensive requirements of calcium and membrane depolarization in both clock regulation and adaptation, L-type voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) appear as a prime candidate in supporting and mediating proper functioning of the circadian system. The impetus to study their role in circadian biology is further substantiated by their prevalent expression in the SCN, with L-type VGCCs appearing to be the most abundant (Nahm et al., 2005). Furthermore, in-vitro studies have demonstrated that voltage-gated calcium channels play an integral role in phase shifts, with L-type antagonists affecting phase advances, and T-type channel antagonists affecting phase delays (Kim et al., 2005). Finally, L-type VGCCs are particularly interesting candidates due to their slow voltage-dependent inactivation, large single channel conductance, and well-defined role in cAMP-dependent protein phosphorylation pathways (Catterall, 2011; Hofmann et al., 2014) a putative cytosolic bridge between electrical activity and the core clock (Atkinson et al., 2011). Despite these conclusions, no one (to our knowledge) has looked in vivo at the functional role of L-type VGCCs in the SCN and their influence on clock-gene regulation and adaptation.

In order to determine the role of the L-type voltage-gated calcium channel in the circadian system, the present study examined both the expression of Cav1.2 (L-type voltage-dependent calcium channel Cacna1c) and its function in circadian rhythmicity and photic entrainment. To this end, brain-specific Cav1.2 knockout mice were assessed on their ability to sustain circadian rhythmicity in constant darkness and phase shift following exposure to light pulses in the early and late subjective night. Our results suggest a time-of-night specific role of the CaV1.2 channel in circadian adaption to light pulses. Although the mechanism remains unclear, the current study suggests a differential mode of calcium signaling in circadian adaption during night.

Experimental Procedures

Animals

Animal care and handling was performed according to the Canton of Fribourg’s law for animal protection authorized by the veterinary office of the Canton of Fribourg, Switzerland and the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986, with local ethical approval. Rev-Erbα−/− mice were obtained from U. Schibler, Geneva (Preitner et al., 2002). Cav1.2 L1 (KO-Gen) and Cav1.2 L2 (conditional gene for nestin-cre) mice (Seisenberger et al., 2000) were backcrossed on a C57BL6 genetic background for 10 generations. Nestin-cre transgenic animals (Tronche et al., 1999) were backcrossed for three generations on a C57BL6 background. The CACNA1C × nestin-cre were on a C57BL6 background backcrossed for four or more generations. To rule out unspecific effects of the nestin-cre transgene, littermate controls expressing cre were used in all experiments involving genetic deletion of Cav1.2 knock-out animals (Langwieser et al., 2010). Cre recombinase is expressed in these mice in neuronal and glia cell precursors and is active only in these brain cells (Zimmerman et al., 1994; Tronche et al., 1999).

Locomotor activity monitoring and light-induced resetting

Mouse handling and housing was as described (Jud et al., 2005). For the analysis of circadian behavior, mice were entrained to a 12-h light/12-h darkness cycle (LD 12:12 h) for two weeks and then released in constant darkness (DD). Running wheel activity was recorded and evaluated using the ClockLab software (Actimetrics). For better visualization of daily rhythms, locomotor activity records were double-plotted which means that each day’s activity is plotted twice, to the right and below that of the previous day. The period length in DD was assessed on 10 consecutive days of stable free-running activity by χ2-periodogram analysis. For the analysis of light-induced resetting, we used an Aschoff type I protocol (Jud et al., 2005). Mice maintained in DD were subjected to brief light pulses (400 l×, 15 minutes) at Circadian Time (CT) 10, 14 or 22. Light seen at CT10 corresponds to light perceived during the subjective day and should not provoke a phase shift of behavioral activity. Light pulses at CT14 or CT22 fall at early or late subjective night and lead to phase delays or phase advances, respectively. Between the presentation of the different light pulses, mice were allowed to stabilize their circadian oscillator for three to four weeks. Light pulses were determined by fitting a regression line through at least 7 onsets of activity before the light pulse and a second regression line through at least 7 onsets of activity after the light pulse. The two days directly after the administration of the light pulse were not taken into account for the calculation of the phase shift. The distance between the two regression lines on the day following the light pulse determined the phase shift.

In situ hybridization

For the analysis of circadian gene expression, mice maintained in LD 12:12 h were released in DD and sacrificed on the third day in DD. Circadian times were calculated for each mouse individually by analyzing its locomotor activity in a wheel-running set-up. Mice were sacrificed at CT0, 6, 12, or 18. For light induction experiments, mice maintained in DD were subjected to a 15-min light pulse at either CT14 or CT22 and sacrificed at CT15 or CT23, respectively. Control animals were sacrificed without prior light exposure at CT15 or CT23.

Specimen preparation and in situ hybridization was performed according to standard protocols (Albrecht et al., 1997). The in situ hybridization probes for Per1, Per2, and c-fos were as described (Albrecht et al., 1997). The probe for Cav1.2 encompassed nucleotides 5202-5484 of the Cav1.2 cDNA and was cloned into a pCR-blunt II-TOPO vector (Invitrogen). The hybridization procedure was briefly as follows: dewaxed, rehydrated, and fixed 7 μm brain sections were permeabilized using proteinase K, and subjected to acetylation. Hybridization with 35S-labelled riboprobes was performed overnight at 55°C in humidified chambers. Stringency washes were carried out at 63°C and sections were incubated with ribonuclease A (Sigma) to degrade unbound radioactively labeled riboprobe. For analysis, sections were exposed to autoradiograph films and the signals were quantified by densitometric analysis (GS-800, Biorad) using the Quantity One software (Biorad). Signals from the SCN were normalized by subtracting the optical density measured in the lateral hypothalamus adjacent to the SCN. For each animal, 6 sections were analyzed and at least 3 animals per genotype were used. For circadian expression of Cav1.2, the highest wild-type average value in each experiment was set to 100% and the other values were calculated relative to this. For light-induced expression, the average value measured in control animals not treated with light in each experiment was defined as 1 and the other values were calculated relative to this to determine the fold induction.

Transactivation Assay

A 1.9kb fragment of the mouse Cav1.2 promoter (nucleotides -1996 to the transcription start site, containing ROREs at -1808, -1586, -1211 and -1029) was cloned into a pGL3 basic vector (Promega) using the following primers: GGCTAGCAGTACGGGTTAAGACAGTTGC (Forward primer; NheI site), GAGATCTCATTGTGGCTTCCAGTTGGGTACC (Reverse primer; BglII site). The potential ROREs were mutated by site directed mutagenesis using the following primers: -1818 GGAAAACACCAAATTAGAGATATCAAGCAGGGAGCTG -1781 (mRE1), -1602 CTGAGACTTTAAAGCTAGCTTTTGTACCCATCAAGTGCACGC -1564 (mRE2), -1230 CTCTGTTCTTGTAAGATCTGGCTGGATTGCCAG -1197 (mRE3), -1047 GTTTTCCAAAATGGCGGATCCAGAACCTATAGTGC -1015 (mRE4). Four consecutive rounds of site-directed mutagenesis were performed on the Cav1.2::luc clone to obtain pGL3_Cav1.2_mRE1-mRE2-mRE3-mRE4 lacking any potential ROREs left, and mutagenesis was verified by DNA sequencing. Expression vectors for Bmal1, Npas2, Rorα1, Rev-Erbα were used as previously described (Langmesser et al., 2008; Schmutz et al., 2010) using β-galactosidase expression vector as control. Transactivation assays were performed in NIH3T3 cells. Empty pGL3-vector and Bmal1::luc reporter were used as negative and positive controls, respectively.

Bioluminescence monitoring

Organotypic slices of the SCN were made as described previously (Hastings et al., 2005). Briefly, mice carrying the floxed allele and Nestin-CRE were crossed into the Per2::luciferase bioluminescent reporter line (Yoo et al., 2004) to generate pups aged between 5 and 10 days old. Brains were removed and coronal slices (300 um thickness) made with a McIlwain Tissue chopper (Mickle Laboratories, Surrey, U.K.) and placed on a Millicell filter culture insert (Millipore, Billerica, CA, USA). After 7 or more days in culture, the slices were transferred to HEPES-buffered recording medium containing luciferin and placed in a light-tight incubator at 37°C immediately below a photon counting head (Model H9319-11, Hamamatsu UK, Welwyn Garden City, Herts, UK) linked to a PC to record photon emissions in 6 minute bins. Time-courses of bioluminescence were analysed by FFT to determine period and amplitude of the oscillation using Brass software running on the BioDare platform (courtesy of Professor Andrew Millar, Centre for Synthetic and Systems Biology, University of Edinburgh, UK).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

For the ChIP experiments, the hypothalamic regions of two mice each including the SCN were homogenized in 1 × PBS supplemented with 1 % formaldehyde, incubated for 5 min at RT and nuclei and chromatin prepared according to (Hampp et al., 2008). DNA fragments precipitated with an antiREV-ERBα antibody (SIGMA SAB2101632) were detected with the following RT-PCR primers and probes: Cav1.2 regulatory region: forward 5’-GTT TTC CAA AAT GGC AGG TCA AGA ACC-3’, reverse 5’-TGT AGT TTC CTG GTA AGA CAC CCA GT-3’, and the probe 5’-FAM-AGA CAC TGA AGC CCA GCG GCA GAC ACC-TAMRA-3’; Bmal1 regulatory region: forward 5’-AGC GAG CCA CGG TGA GTG T-3’, reverse 5’-CCG GGA ACT CGC GAC CC-3’, and probe 5’-FAM-AGC CGT CTC GGG GCG TCC CG-TAMRA-3’; Dbp intron1: forward 5’-TCC ATG TGA CCC TGC GAG GC-3’, reverse 5-CCT GGA GTC CTA GGG GAA GGG-3’, and probe 5’-FAM-CCC GCC CAA GCC CGT GTC TGC-TAMRA-3’.

Results

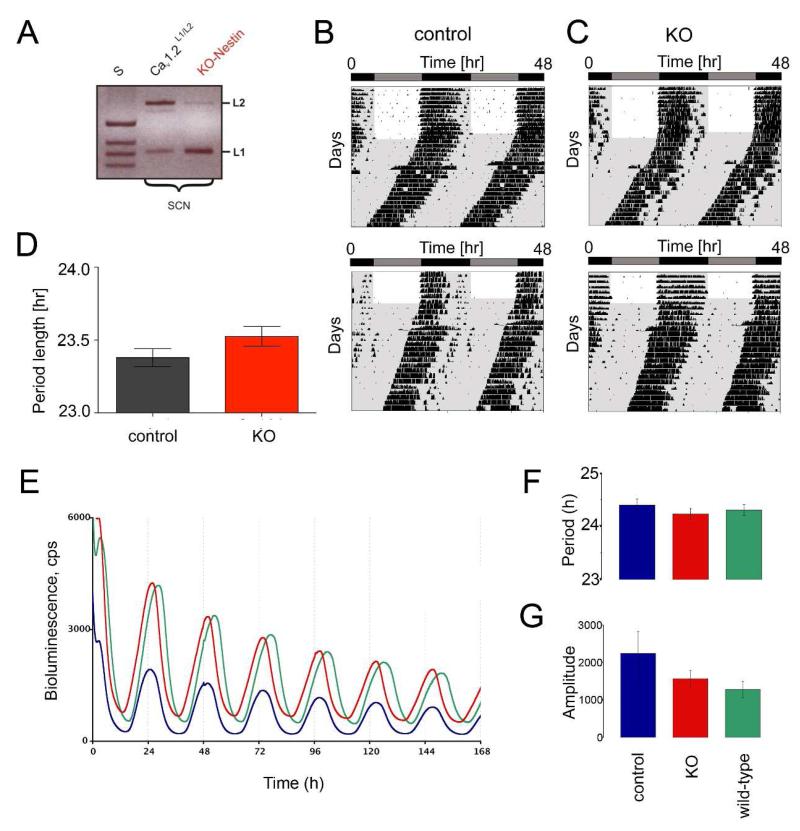

As a first step in determining whether Cav1.2 is implicated in the regulation of the circadian clock, we characterized the daily activity of brain-specific Cav1.2−/− knockout mice (Cav1.2−/− KO) that did not express Cav1.2 in the SCN (Fig. 1A). These animals were compared to wild-type control littermates and assessed on their clock parameters including period, total daily wheel-running activity, and precision of daily onset of activity. Animals were entrained to a 12-hour light/dark (LD) cycle (12:12 LD) and then released into constant darkness (DD). Under both conditions the two groups displayed stable free-running activity rhythms and did not differ in any of the aforementioned parameters (Fig. 1B-D). Cav1.2−/− knockout mice exhibited a period length of 23.38 h ± 0.06 (n=12) while control animals showed similar period lengths of 23.52 h ± 0.07 (n=12), thus revealing that the Cav1.2 channel does not play a role in circadian regulation at the behavioral level (Fig. 1D). To substantiate this claim, Cav1.2 KO and wild-type mice were crossed into a PER2:LUC reporter line to measure period and amplitude in SCN slice cultures (Fig. 1E). The results revealed no significant influence of the Cav1.2 channel in clock gene regulation, as normal rhythmicity was sustained in wild-type and Cav1.2 knockout mice (Fig. 1F), as was amplitude (Fig. 1G) in cycling of the bioluminescence signal. With the indication that the Cav1.2 channel does not regulate circadian period, we next sought to determine if the channel was involved in the adaptation of the clock to changing lighting conditions.

Figure 1. Cav1.2 is dispensable for rhythmic circadian locomotor behavior under constant conditions.

(A) Cav1.2 mRNA expression is absent in the SCN of brain-specific Cav1.2 KO mice (KO-nestin), with L1 representing the KO allele and L2 the floxed allele. Representative locomotor activity records of control animals (B) and Cav1.2 KO mice (C) maintained in a 12-h light/ 12-h darkness cycle (LD 12:12 h) or constant darkness (DD) are shown. Locomotor activity is represented as black bars and double-plotted. Grey shaded areas indicate phases of darkness. (D) Average free-running period of control and Cav1.2 KO animals maintained in DD as determined by χ2-periodogram analysis (mean ± SEM; n=12; unpaired t-test, p>0.05). (E) Bioluminescence of SCN slices in culture (F) period of bioluminescence of SCN slices (G) amplitude of bioluminescence of SCN slices. There are no significant differences between genotypes neither for period nor for amplitude. One-way ANOVA p>0.05, n=3. Data presented as mean ± SEM. Control = Cav1.2 L1/L2:: Per2luc (floxed wild-type littermates), KO = Cav1.2 KO-nestin:: Per2luc, wild-type:: Per2luc.

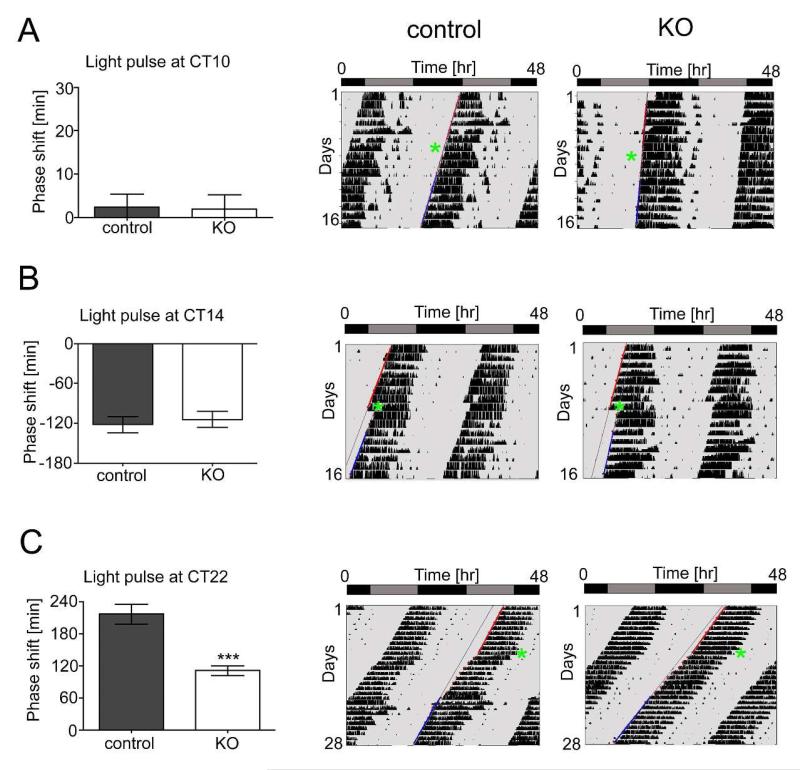

Entrainment to a changing light schedule requires both calcium-mediated second messenger signaling and neuronal excitation: therefore we expected the Cav1.2 channel to play a role in entrainment. To assess this function, animals were exposed to a 15-minute light pulse at CT10, CT14, or CT22 and their phase-shifts assessed. Since animals do not respond to light pulses during the subjective day (CT0-12), as expected, both control (2.3 ± 3.1 min, n=12) and Cav1.2−/− KO mice (2 ± 3.2 min, n=11) did not display phase-shifts when subjected to light at CT10 (p>0.05, t-test) (Fig. 2A). Exposure to a 15-minute light pulse in the early subjective night (CT14), however, evoked normal phase delays in both control (−122 ± 12 min, n=12) and Cav1.2−/− KO mice (−114 ± 12 min, n=11) (p>0.05, t-test) (Fig. 2B). Application of a 15-minute light pulse in the late subjective night (CT22) evoked in both genotypes a phase advance. Intriguingly, the phase advance was significantly reduced (to ca. 50%) in the Cav1.2−/− KO mice (110 ± 9 min, n=10) compared to wild-type control animals (216 ± 19 min, n=11), thus uncovering a specific role for the Cav1.2 channel in the late night (p<0.001, t-test) (Fig. 2C). Overall, these results reveal that the Cav1.2−/− KO mice, following a light pulse in the late subjective night, display an impaired ability to phase advance. These results suggest that the Cav1.2 L-type voltage-gated calcium channel plays a unique role in the adaptation to light during the late-subjective night.

Figure 2. Cav1.2 KO mice show smaller phase shifts after a light pulse at late subjective night.

Shown are the quantifications of the phase shifts observed after brief light pulses presented at different times of the day (left panels) and representative locomotor activity records showing the locomotor activity before and after light administration for control (middle panels) and Cav1.2 KO mice (right panels). Red lines in the activity recordings represent the onset of activity before the light pulse and blue lines represent the onset after the light pulse. Green asterisks indicate the timing of the light pulse. Light pulses were administered at CT10 (A), CT14 (B) or CT22 (C). Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n=10-12) and significant differences were determined by unpaired t-test (*** p<0.001).

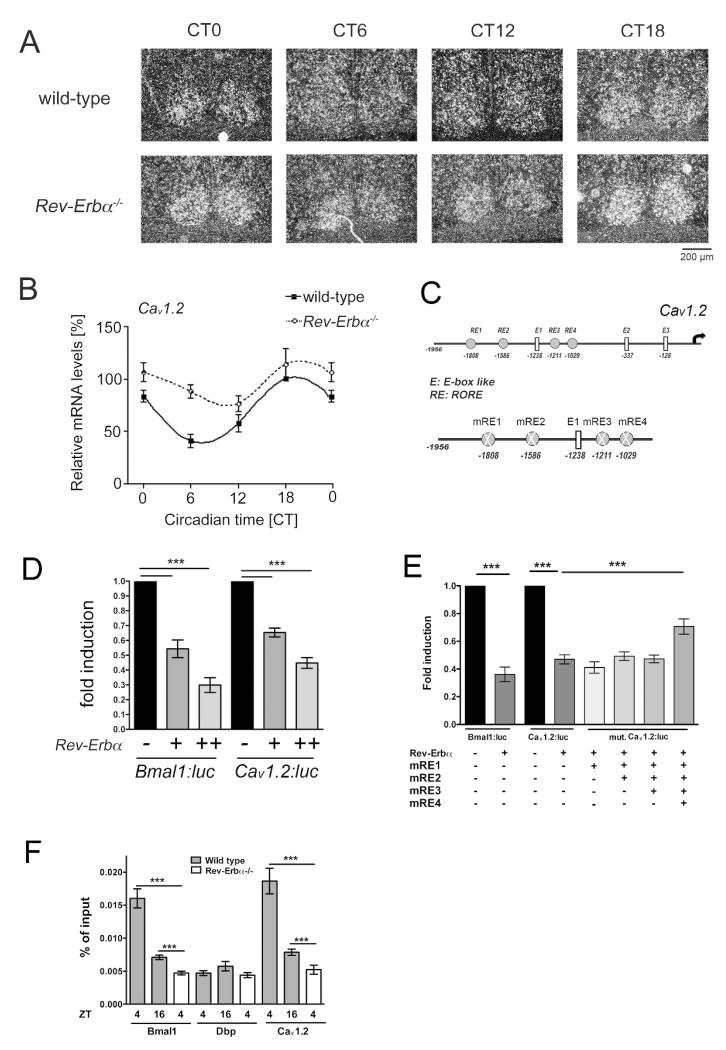

With the knowledge that Cav1.2−/− KO animals display disrupted phase-advances when subjected to light in the late subjective night, we next sought to determine whether our behavioral phenotype could be further delineated at the molecular level. Utilizing in situ hybridization, Cav1.2 mRNA transcripts were targeted in wild-type mouse SCN at hours 0, 6, 12, and 18. As hypothesized, Cav1.2 was expressed rhythmically in the SCN, with expression peaking during the late subjective night (CT18) and dropping to its lowest point during the day (CT6) (Fig. 3A top row, B solid lines). The peak of expression during the late subjective night suggests an important function of the Cav1.2 channel during this time of day. This is in line with the observed defect in the phase-advancing ability after a light pulse at CT22 of mice deficient in this channel.

Figure 3. Cav1.2 is expressed in a circadian fashion in the SCN and is regulated by REV-ERBα.

Expression of Cav1.2 in the SCN of wild-type and Rev-Erbα−/− mice maintained in constant darkness as revealed by in situ hybridization. Animals were sacrificed at Circadian times (CT) 0, 6, 12, 18. (A) Representative micrographs reveal rhythmic expression of Cav1.2 in the SCN of wild-type animals (top row) and Rev-erbα KO (bottom row). The location within the SCN was determined by Hoechst dye staining (gray). Cav1.2 expression signal is shown in white. Bar, 200 μm. (B) Quantification of the Cav1.2 expression signal by densitometric analysis of autoradiography films. Shown are the relative optical densities in the SCN of wild-type and Rev-Erbα−/− KO mice (mean ± SEM, n=3). (C) Schematic representation of the ROREs in the Cav1.2 promoter. The numbers represent the nucleotide at the end of the element. (D) Transfection experiments in NIH3T3 cells show a repression potential of REV-ERBα that is similar for both the Bmal1::luc and the Cav1.2::luc reporter constructs (n=5, ***p<0.001, mean ± SD). (E) Mutation of the ROREs 1-4 (mRE1-mRE4) in the Cav1.2 promoter (n=5, ***p<0.001, mean ± SD). (F) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) reveals time of day dependent binding of REV-ERBα on the Cav1.2 promoter in hypothalamic tissue including the SCN (n=4, ***p<0.001, mean ± SEM, one-way ANOVA).

Since the Cav1.2−/− KO mice displayed the opposite phase-shifting phenotype compared to Rev-Erbα−/− KO animals in response to a light pulse at CT22 (with Rev-Erbα−/− KO exhibiting increases in phase-advances), we were curious to see whether REV-ERB α regulates Cav1.2 expression, which may explain the Rev-Erbα−/− KO phase-advancing phenotype (Preitner et al., 2002). To this end, we employed in situ hybridization to measure the expression of Cav1.2 mRNA in Rev-Erbα−/− KO animals (Preitner et al., 2002). As hypothesized, Cav1.2 mRNA was significantly enhanced at all time points, thus proposing a repressive function of the nuclear receptor REV-ERBα in regulating Cav1.2 expression (Fig. 3A lower panels, B dashed line). Furthermore, circadian amplitudes of Cav1.2 expression were largely damped by the loss of Rev-Erbα, thus indicating that REV-ERBα actively represses Cav1.2 expression during the day while permitting its induction during the night phase. Since a slight repression of Cav1.2 can still be observed at CT12 it is likely that additional factors regulate the Cav1.2 promoter. The results reveal circadian control of the mRNA of the Cav1.2 channel with its expression being repressed during the day and then liberated during the early night, with expression peaking during the late night.

To further explore the molecular regulation of Cav1.2, we performed in vitro transactivation experiments in NIH-3T3 cells using a Cav1.2-luciferase (Cav1.2::luc) reporter plasmid. We analyzed the promoter region of Cav1.2 and predicted putative REV-ERBα binding sites (so called ROREs, Fig. 3C) and tested whether this nuclear receptor can regulate Cav1.2 promoter activity. As expected, co-transfection of increasing amounts of REV-ERBα significantly reduced the transcription of Cav1.2 similarly to the repression seen using a Bmal1-luciferase (Bmal1::luc) reporter (Figure 3D). In contrast, the activating nuclear receptor RORα1 induced the Cav1.2::luc reporter activity in a similar manner as the Bmal1::luc reporter (Fig. S1A). To verify that REV-ERBα was acting at the RORE elements in the Cav1.2 promoter, we performed site-directed mutagenesis to insert mutations into the predicted RORE elements (Fig. 3C, mRE). Absence of RORE elements 1-3 did not result in decreased repression by REV-ERBα (Fig. 3E, mRE1-3). However, by mutagenizing all four RORE elements, the expression of Cav1.2 was partially rescued as REV-ERBα was unable to perform its repressive function (Figure 3E, mRE1-4). That the rescue is only partial may be due to distant ROREs that are not included in our reporter construct. Since we also identified putative E-box elements (E1-E3) in the promoter of Cav1.2, we performed further transactivation experiments with the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors BMAL1 and NPAS2 to test whether they regulated Cav1.2::luc reporter activity but we did not observe an increase in Cav1.2 transcription (Fig. S1B).

Finally, to confirm the binding of REV-ERBα to the Cav1.2 promoter in vivo, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments in hypothalamic tissue that included the SCN. As anticipated, our controls demonstrated that REV-ERBα binds the BMAL1 promoter in wild-type but not Rev-Erbα−/− KO animals (positive control) and REV-ERBα does not bind to the Dbp promoter in wild-type nor Rev-Erbα−/− KO animals (negative control) (Figure 3F). In wild-type animals, REV-ERBα binding to the Cav1.2 promoter was significantly enhanced at ZT4 with binding dropping at ZT16. In the Rev-Erbα−/− KO animals, the signal is completely lost (Figure 3F). These results are consistent with the previous results obtained with the Cav1.2::luc reporter and in situ hybridization that demonstrate the repressive role of REV-ERBα in Cav1.2 expression (Figure 3D-E), while confirming that the peak levels of Cav1.2 mRNA induction overlaps with the lowest levels of REV-ERBα binding and vice versa (Fig. 3A, F).

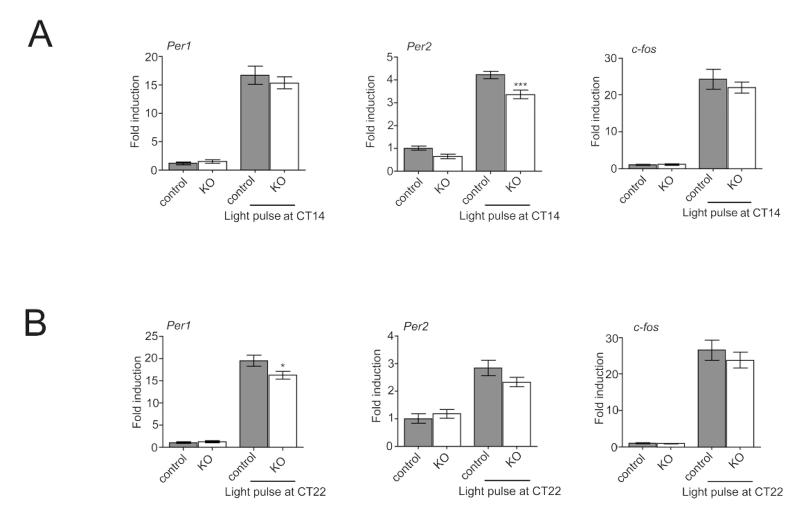

Since the circadian clock regulates Cav1.2 expression by REV-ERBα and displays attenuated phase advances, we next sought to determine whether the Cav1.2 channel plays a role in clock gene expression following a 15-minute light pulse at CT14 or CT22. As previously reviewed, following a light pulse during the subjective night, c-fos, Per1, and Per2 are induced (albeit with different kinetics) and through this mechanism, the circadian clock is directly modulated (Albrecht et al., 1997; Albrecht et al., 2001; Yan and Silver, 2002; Golombek and Rosenstein, 2010). We performed in situ hybridization targeting the clock genes Per1 and Per2 and the immediate-early gene c-fos 45 minutes after the light pulses. It appears that in Cav1.2−/− KO mice the trend is an attenuated induction of gene expression, which may be due to a general effect of the null mutation on photo-responsiveness in the SCN. However, this attenuation appears not to be equal for all genes. Following a 15-minute light pulse in the early subjective night (CT14), Cav1.2−/− KO mice unexpectedly exhibited significantly less induction of Per2 but did not show any differences in Per1 or c-fos (Fig. 4). When challenged during the late subjective night (CT22), Cav1.2−/− KO mice displayed a significant lower induction of Per1 without displaying any differences in c-fos or Per2 expression (Fig. 5). In sum, these results indicate that the Cav1.2 channel influences clock gene induction during the early and late subjective night.

Figure 4. Induction of Per1, Per2 and c-fos mRNA after a light pulse in the SCN.

(A) Induction of Per1 (left), Per2 (middle), and c-fos (right) mRNA expression in the SCN of control and Cav1.2 KO animals after a light pulse administered at CT14 as revealed by in situ hybridization. Animals treated with light at CT14 and animals not exposed to light were sacrificed at CT15. Shown is the mean ± SEM (n=3) of relative induction values as calculated by comparison of expression levels in light-treated mice with control animals not treated with light. Significant differences were determined by 1-way Anova analysis. (B) Induction of Per1 (left), Per2 (middle), and c-fos (right) expression in the SCN of control and Cav1.2 KO mice in response to a light pulse applied at CT22. Animals treated with light at CT22 and animals not exposed to light were sacrificed at CT23. Shown is the mean ± SEM of relative induction values (n=3-4). Differences were analyzed by one-way Anova (*p<0.05).

Discussion

In the present study, we report a time-of-night specific role of the L-type voltage-gated calcium channel Cav1.2 in setting the circadian clock during the late night. Although the clock appears to be self-sufficient in regulating its output and clock gene expression in the absence of the Cav1.2 channel (Figs. 1, 3B), the clock resetting mechanism is largely affected in the late night as phase advances are significantly reduced after presentation of a light pulse (Fig. 3). The finding that Cav1.2 mRNA expression is rhythmic with a peak during the late night (Fig. 3A) suggests that the Cav1.2 channel is specifically implicated in clock resetting during the late night. It appears that the gene regulation of the Cav1.2 channel is wrapped neatly into the circadian clock machinery as its expression is controlled by the repressive function of the nuclear receptor REV-ERBα (Figure 3B). This is evidenced by the deregulation of Cav1.2 mRNA expression in Rev-Erbα−/− KO animals, the ability of REV-ERBα to repress a Cav1.2 luciferase reporter in transfection experiments and ChIP experiments, which confirm that REV-ERBα binds to the Cav1.2 promoter in vivo (Figure 3D-E). Finally, Cav1.2 appears to be one of the factors that contributes to clock gene induction following a light pulse as the induction of the Period genes are attenuated in the Cav1.2−/− KO mice with Per2 affected during the early night (Fig. 4A) and Per1 during the late night (Fig. 4B).

Although the lack of the Cav1.2 channel did not affect clock period and the adaptation of the clock to light pulses during the early night it is very possible that compensatory mechanisms took over in Cav1.2 knockout mice due to the high prevalence of VGCCs in the SCN. There are four L-type calcium channels in total with two (Cav1.2 and Cav1.3) being specifically implicated in neuronal gene expression (Catterall, 2011). Furthermore, there are five distinct forms of voltage-gated calcium channels in total and their expression have all been documented in the SCN (Nahm et al., 2005). Thus the findings of this study are significant as the loss of a single L-type VGCC channel influences the phase-shifting ability of mice in the late night. What role the remaining calcium channels play has yet to be determined.

One explanation for the lack of an effect of the loss of the Cav1.2 channel on phase delays may come from the function of the intracellular ryanodine receptors. The light induced signal transduction pathway for the early night may predominantly affect the ryanodine receptors, which then release calcium from intracellular stores (Ding et al., 1998) and hence extracellular calcium influx via Cav1.2 channels induced by membrane depolarization may play a minor or no role in the response to light perceived during the early night. In contrast, during the late night ryanodine receptors are not responsive to light (Ding et al., 1998) and extracellular calcium signaling via calcium channels located in the synaptic membrane like the L-type Ca2+ channel Cav1.2 may become the driving force for phase advances. Our finding is supported by the study of Kim et al. (2005) who applied L-type Ca2+ channel blockers to hypothalamic slices and found that they affected phase advances but not phase delays. In contrast, T-type Ca2+ channel blockers modulated the phase delay response but did not affect phase advances (Kim et al., 2005). Interestingly, also extra-SCN areas that signal to the SCN appear to be involved in the clock resetting process. These extra SCN pathways appear to rely on NPQ-type Cav2.1 channels and have a direct impact on the phase of the SCN (van Oosterhout et al., 2008). Taken together it appears that Ca2+ channels play an important role in clock resetting. T-type Ca2+ channels are important for phase delays and L-type Ca2+ channels are important for phase advances. Extra SCN signals to the SCN, which elicit phase advances appear to involve N-type Cav2.1 channels. The observation that phase delays are usually larger than advances may be due to the additional assistance of ryanodine receptors in the delay response.

The current study provides a solid basis to begin to parse out the functional roles of voltage-gated calcium channels in the SCN and determine their specific function in circadian timekeeping. Nahm et al. 2005 have already demonstrated the widespread expression of VGCCs in the SCN and rhythmic expression of P/Q and T-type channels while Kim et al. 2005 have proposed a role for T-type VGCCs in mediating phase delays in the early night. Therefore, it seems very likely that many of the VGCCs are under control of the circadian clock and may play differential roles in circadian regulation and adaptation. Further in vivo studies are required to fill this gap and determine their functional roles.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Antoinette Hayoz, Stéphanie Baeriswyl-Aebischer (Fribourg) and Johanna E. Chesham (MRC-LMB) for expert technical assistance and Dr. U. Schibler for Rev-erbα KO mice. Funding by the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Velux Foundation, the State of Fribourg, the Medical Research Council, U.K. and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Albrecht U, Sun ZS, Eichele G, Lee CC. A differential response of two putative mammalian circadian regulators, mper1 and mper2, to light. Cell. 1997;91:1055–1064. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80495-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht U, Zheng B, Larkin D, Sun ZS, Lee CC. MPer1 and mper2 are essential for normal resetting of the circadian clock. Journal of biological rhythms. 2001;16:100–104. doi: 10.1177/074873001129001791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asher G, Schibler U. Crosstalk between components of circadian and metabolic cycles in mammals. Cell metabolism. 2011;13:125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson SE, Maywood ES, Chesham JE, Wozny C, Colwell CS, Hastings MH, Williams SR. Cyclic AMP signaling control of action potential firing rate and molecular circadian pacemaking in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Journal of biological rhythms. 2011;26:210–220. doi: 10.1177/0748730411402810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brancaccio M, Maywood ES, Chesham JE, Loudon AS, Hastings MH. A Gq-Ca2+ axis controls circuit-level encoding of circadian time in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neuron. 2013;78:714–728. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA. Voltage-gated calcium channels. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2011;3:a003947. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colwell CS. Circadian modulation of calcium levels in cells in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. The European journal of neuroscience. 2000;12:571–576. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00939.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding JM, Buchanan GF, Tischkau SA, Chen D, Kuriashkina L, Faiman LE, Alster JM, McPherson PS, Campbell KP, Gillette MU. A neuronal ryanodine receptor mediates light-induced phase delays of the circadian clock. Nature. 1998;394:381–384. doi: 10.1038/28639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoki R, Kuroda S, Ono D, Hasan MT, Ueda T, Honma S, Honma K. Topological specificity and hierarchical network of the circadian calcium rhythm in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:21498–21503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214415110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima T, Shimazoe T, Shibata S, Watanabe A, Ono M, Hamada T, Watanabe S. The involvement of calmodulin and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in the circadian rhythms controlled by the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neuroscience letters. 1997;227:45–48. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00297-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golombek DA, Rosenstein RE. Physiology of circadian entrainment. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:1063–1102. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00009.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampp G, Ripperger JA, Houben T, Schmutz I, Blex C, Perreau-Lenz S, Brunk I, Spanagel R, Ahnert-Hilger G, Meijer JH, Albrecht U. Regulation of monoamine oxidase A by circadian-clock components implies clock influence on mood. Current biology: CB. 2008;18:678–683. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings MH, Reddy AB, McMahon DG, Maywood ES. Analysis of circadian mechanisms in the suprachiasmatic nucleus by transgenesis and biolistic transfection. Methods in enzymology. 2005;393:579–592. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)93030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann F, Flockerzi V, Kahl S, Wegener JW. L-type CaV1.2 calcium channels: from in vitro findings to in vivo function. Physiol Rev. 2014;94:303–326. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00016.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda M, Sugiyama T, Wallace CS, Gompf HS, Yoshioka T, Miyawaki A, Allen CN. Circadian dynamics of cytosolic and nuclear Ca2+ in single suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. Neuron. 2003;38:253–263. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin RP, Allen CN. Calcium response to retinohypothalamic tract synaptic transmission in suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2007;27:11748–11757. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1840-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jud C, Schmutz I, Hampp G, Oster H, Albrecht U. A guideline for analyzing circadian wheel-running behavior in rodents under different lighting conditions. Biological procedures online. 2005;7:101–116. doi: 10.1251/bpo109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DY, Choi HJ, Kim JS, Kim YS, Jeong DU, Shin HC, Kim MJ, Han HC, Hong SK, Kim YI. Voltage-gated calcium channels play crucial roles in the glutamate-induced phase shifts of the rat suprachiasmatic circadian clock. The European journal of neuroscience. 2005;21:1215–1222. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornhauser JM, Cowan CW, Shaywitz AJ, Dolmetsch RE, Griffith EC, Hu LS, Haddad C, Xia Z, Greenberg ME. CREB transcriptional activity in neurons is regulated by multiple, calcium-specific phosphorylation events. Neuron. 2002;34:221–233. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00655-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmesser S, Tallone T, Bordon A, Rusconi S, Albrecht U. Interaction of circadian clock proteins PER2 and CRY with BMAL1 and CLOCK. BMC molecular biology. 2008;9:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-9-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langwieser N, Christel CJ, Kleppisch T, Hofmann F, Wotjak CT, Moosmang S. Homeostatic switch in hebbian plasticity and fear learning after sustained loss of Cav1.2 calcium channels. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30:8367–8375. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4164-08.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundkvist GB, Kwak Y, Davis EK, Tei H, Block GD. A calcium flux is required for circadian rhythm generation in mammalian pacemaker neurons. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2005;25:7682–7686. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2211-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahm SS, Farnell YZ, Griffith W, Earnest DJ. Circadian regulation and function of voltage-dependent calcium channels in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2005;25:9304–9308. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2733-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennartz CM, de Jeu MT, Bos NP, Schaap J, Geurtsen AM. Diurnal modulation of pacemaker potentials and calcium current in the mammalian circadian clock. Nature. 2002;416:286–290. doi: 10.1038/nature728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preitner N, Damiola F, Lopez-Molina L, Zakany J, Duboule D, Albrecht U, Schibler U. The orphan nuclear receptor REV-ERBalpha controls circadian transcription within the positive limb of the mammalian circadian oscillator. Cell. 2002;110:251–260. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00825-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmutz I, Ripperger JA, Baeriswyl-Aebischer S, Albrecht U. The mammalian clock component PERIOD2 coordinates circadian output by interaction with nuclear receptors. Genes & development. 2010;24:345–357. doi: 10.1101/gad.564110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seisenberger C, Specht V, Welling A, Platzer J, Pfeifer A, Kuhbandner S, Striessnig J, Klugbauer N, Feil R, Hofmann F. Functional embryonic cardiomyocytes after disruption of the L-type alpha1C (Cav1.2) calcium channel gene in the mouse. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275:39193–39199. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006467200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadler F, Schmutz I, Schwaller B, Albrecht U. Lack of calbindin-D28k alters response of the murine circadian clock to light. Chronobiology international. 2010;27:68–82. doi: 10.3109/07420521003648554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronche F, Kellendonk C, Kretz O, Gass P, Anlag K, Orban PC, Bock R, Klein R, Schutz G. Disruption of the glucocorticoid receptor gene in the nervous system results in reduced anxiety. Nature genetics. 1999;23:99–103. doi: 10.1038/12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Oosterhout F, Michel S, Deboer T, Houben T, van de Ven RC, Albus H, Westerhout J, Vansteensel MJ, Ferrari MD, van den Maagdenberg AM, Meijer JH. Enhanced circadian phase resetting in R192Q Cav2.1 calcium channel migraine mice. Annals of neurology. 2008;64:315–324. doi: 10.1002/ana.21418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AE, Chen WG, Dalva MB, Dolmetsch RE, Kornhauser JM, Shaywitz AJ, Takasu MA, Tao X, Greenberg ME. Calcium regulation of neuronal gene expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:11024–11031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191352298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L, Silver R. Differential induction and localization of mPer1 and mPer2 during advancing and delaying phase shifts. The European journal of neuroscience. 2002;16:1531–1540. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02224.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SH, Yamazaki S, Lowrey PL, Shimomura K, Ko CH, Buhr ED, Siepka SM, Hong HK, Oh WJ, Yoo OJ, Menaker M, Takahashi JS. PERIOD2::LUCIFERASE real-time reporting of circadian dynamics reveals persistent circadian oscillations in mouse peripheral tissues. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:5339–5346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308709101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman L, Parr B, Lendahl U, Cunningham M, McKay R, Gavin B, Mann J, Vassileva G, McMahon A. Independent regulatory elements in the nestin gene direct transgene expression to neural stem cells or muscle precursors. Neuron. 1994;12:11–24. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.