Abstract

Background

Obesity, defined as pathologically increased body mass index (BMI), is strongly related to an increased risk for numerous common cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. It is particularly associated with insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, and systemic oxidative stress and represents the most important risk factor for type 2 diabetes (T2D). However, the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying these associations are still not completely understood. Therefore, in order to identify potentially disease-relevant BMI-associated gene expression signatures, a transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS) on BMI was performed.

Methods

Whole-blood mRNA levels determined by array-based transcriptional profiling were correlated with BMI in two large independent population-based cohort studies (KORA F4 and SHIP-TREND) comprising a total of 1977 individuals.

Results

Extensive alterations of the whole-blood transcriptome were associated with BMI: More than 3500 transcripts exhibited significant positive or negative BMI-correlation. Three major whole-blood gene expression signatures associated with increased BMI were identified. The three signatures suggested: i) a ratio shift from mature erythrocytes towards reticulocytes, ii) decreased expression of several genes essentially involved in the transmission and amplification of the insulin signal, and iii) reduced expression of several key genes involved in the defence against reactive oxygen species (ROS).

Conclusions

Whereas the first signature confirms published results, the other two provide possible mechanistic explanations for well-known epidemiological findings under conditions of increased BMI, namely attenuated insulin signaling and increased oxidative stress. The putatively causative BMI-dependent down-regulation of the expression of numerous genes on the mRNA level represents a novel finding. BMI-associated negative transcriptional regulation of insulin signaling and oxidative stress management provide new insights into the pathogenesis of metabolic syndrome and T2D.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12920-015-0141-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Transcriptomics, Transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS), BMI, Obesity, Insulin resistance, Type 2 diabetes, Oxidative stress, Insulin signaling

Background

The past two decades saw obesity surpass malnutrition and infectious diseases as the greatest contributors to morbidity and mortality. This obesity epidemic is also driving the world-wide endemic development of type 2 diabetes (T2D) [1]. Body mass index, the most commonly used anthropometric measure in the context of health risks related to obesity, is correlated with metabolic disorders, cardiovascular and all-cause mortality [2].

Regulation of body weight is complex and affected by genetic as well as environmental factors. Heritability of anthropometric measures such as BMI is as high as 40 to 70 % [3]. This prompted intense research for underlying genetic factors to unravel the metabolic networks controlling body mass [4]. Monogenic mutations such as those described for LEP, LEPR, POMC, and MC4R cause only a minority of obesity cases whereas in most individuals obesity is based on a polygenic predisposition amplified by an obesogenic Western lifestyle [4].

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have detected a large number of genes modulating levels of and susceptibility to adiposity. However, the effect sizes of these common variants are small, with a limited predictive value for obesity risk [5]. Gene expression studies have emerged as a promising approach for the analysis of gene regulatory networks and might allow the identification of pathways linked to body mass regulation [6]. Previous studies on obese subjects demonstrated that blood cells represent a robust model to study the maintenance of energy homeostasis and its interaction with body weight [7].

In order to identify potentially disease-relevant BMI-related gene expression signatures, we determined whole-blood mRNA levels of 1977 individuals from two large independent population-based cohort studies (Kooperative Gesundheitsforschung in der Region Augsburg (KORA) and Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP-TREND)) within the frame of the DZHK MetaXpress consortium by array-based transcriptional profiling and subsequently correlated mRNA abundances and BMI in the current study. In addition to the demonstration of extensive BMI-associated alterations of the whole-blood transcriptome, three distinct gene expression signatures associated with increased BMI were detected. The observation of BMI-associated decreased expression of genes involved in insulin signaling and protection against oxidative stress provides new insight into the pathomechanisms underlying obesity-mediated insulin resistance and systemic oxidative stress contributing to the development of type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Methods

Study populations

All subjects were of European ancestry. Written, informed consent has been obtained from participants and the studies were approved by the Ethics Committees of the University of Greifswald and the Bavarian Medical Association for SHIP and KORA, respectively.

KORA F4

The KORA (Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg) F4 survey has been described before [8]. Briefly, 1653 individuals aged 55 to 74 years from the city Augsburg in the southeast of Germany and two adjacent counties participated in the population-based KORA survey S4 that was conducted between 1999 and 2001 [8]. This cohort was reinvestigated in the KORA survey F4 in 2006–2008. Study design, sampling method and data collection have been described in detail elsewhere [9, 10]. The study presented here is based on a KORA F4 subsample of 988 individuals aged 62 to 81 years.

SHIP-TREND

The Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP) is a longitudinal population-based cohort study in West Pomerania, a region in the northeast of Germany, assessing the prevalence and incidence of common population-relevant diseases and their risk factors. Baseline examinations for SHIP-TREND were carried out between 2008 and 2012, comprising 4,420 participants. Study design and sampling methods were previously described [11]. The present project is based on a subset of 989 individuals aged 20 to 81 years of the SHIP-TREND study population.

Anthropometric measurements

Weight and height were measured using standard protocols as described elsewhere [8]. For the anthropometric measurements, calibrated, digital scales (Seca 862, Seca Germany) and a measuring stick (Seca 220, Seca, Germany) were used. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in square meters.

Preparation and quality control of whole-blood RNA and transcriptome analysis

Blood sample collection as well as RNA preparation were described in detail elsewhere [12]. Briefly, whole-blood samples were collected from participants of both studies between 8:00 a.m. and noon after overnight fasting and stored in PAXgene Blood RNA Tubes (BD). Subsequently, RNA was prepared using the PAXgene™ Blood miRNA Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Purity and concentration of RNA were determined using a NanoDrop ND-1000 UV–vis Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). To ensure a constantly high quality of the RNA preparations, all samples were analyzed using RNA 6000 Nano LabChips (Agilent Technologies, Germany) on a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples exhibiting an RNA integrity number (RIN) less than seven were excluded from further analysis. The Illumina TotalPrep-96 RNA Amplification Kit (Ambion, Darmstadt, Germany) was used for reverse transcription of 500 ng RNA into double-stranded (ds) cDNA and subsequent synthesis of biotin-UTP-labeled antisense-cRNA using this cDNA as the template. Finally, in total 3,000 ng of cRNA were hybridized with a single array on the Illumina HumanHT-12 v3 BeadChips, followed by washing and detection steps in accordance with the Illumina protocol. BeadChips were scanned using the Illumina Bead Array Reader.

The Illumina software GenomeStudio V 2010.1 was used to read the generated raw data, for imputation of missing values and sample quality control. Subsequently, raw gene expression data were exported to the statistical environment R, version 2.14.2 (R Development Core Team 2011). Data were normalized using quantile normalization and log2-transformation using the lumi 2.8.0 package from the Bioconductor open source software (http://www.bioconductor.org/).

Gene expression data analysis

Individuals with missing BMI values or at least one of the covariates values (KORA F4: n = 5, SHIP-TREND: n = 0) were excluded from the analysis. In linear regression models, gene expression levels were regressed on BMI with adjustment for age, sex, red blood cell count (RBC), white blood cell count (WBC), hematocrit, platelet count, RNA quality (RIN), plate layout after RNA amplification (96 well plates), and sample storage time (time between blood donation and RNA preparation) [12]. It has been demonstrated earlier that KORA F4 and SHIP-TREND are comparable and can be meta-analyzed, even if the two cohorts differ in some minor aspects [12]. A sample size-weighted z-score based meta-analysis was used to combine the gene expression data from both cohorts (n = 1977) using the metafor meta-analysis package for R, version 1.4-0 (http://www.jstatsoft.org/v36/i03/). In order to test if any detected associations between BMI and whole-blood mRNA levels were mediated by BMI-dependent shifts in the proportions of different blood cell sub-types, an additional analysis with adjustment for relative lymphocyte, neutrophil, basophil, eosinophil and monocyte count was performed in SHIP-TREND, where these parameters were available for all individuals. Adjusting for these parameters did not substantially change the obtained results. The corresponding R2-values for effect size (beta), standard error, and -log10 p-value of the meta-analysis were 94, 99, and 91 %, respectively. The effect of an additional adjustment for homeostasis model assessment – insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) on the results was negligible. The corresponding R2-values for effect size (beta), standard error, and -log10 p-value of the meta-analysis were 99.56, 99.98, and 99.39 %, respectively. Only the 12,778 transcripts with a detection rate (defined as the proportion of observations with detection p-value < 0.05) above 50 % in both cohorts were considered. The Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) was used to correct for multiple testing. Associations with an FDR < 0.01 were considered statistically significant. Pathway analyses were performed based on all significant gene-specific probes using the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software tool (IPA build version: 338830 M, content version: 23814503, release date: 2015-03-22; analysis Date: 2015-06-19; http://www.ingenuity.com/). The database underlying IPA is referred to as the Ingenuity Knowledge Base. Based on the Illumina ProbeIDs, the IPA software allocates probes to annotated genes and to corresponding objects in the Ingenuity Knowledge Base. The reference set was restricted to genes represented on the IlluminaHT-12 v3 BeadChip, and only human annotations were considered. In case multiple probes mapped to one gene, the probe exhibiting the smallest p-value was considered for downstream analyses. Pathway analyses were performed with IPA’s Core Analysis module. Overrepresentations of BMI-associated genes in functional categories and canonical pathways were calculated using a right-tailed Fisher’s exact test with a significance level of 0.05 after Benjamini and Hochberg correction. The resulting p-value identifies over-representation of input genes in a given process. Gene enrichment in canonical pathways is described by the ratio of the number of input genes that map to the pathway divided by the total number of genes in this pathway. Permutation analysis, which is described in detail in Additional file 1: Supplemental Materials, was performed for evaluating robustness of Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) and identifying potentially false positive over-representations.

For an overview of the number of significant and annotated probes as well as genes, see Additional file 2: Figure S1–S34. The detailed workflow for the analysis of Illumina gene expression microarray data was described recently within the MetaXpress consortium [12].

Results and discussion

General results

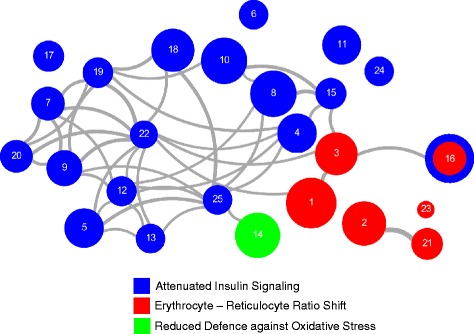

Within the MetaXpress Consortium of the German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK), whole-blood mRNA levels of 1977 participants of the two independent population-based studies SHIP-TREND and KORA F4 (Table 1) were determined by array-based transcriptional profiling. Subsequently, whole-blood mRNA levels were associated with the phenotype BMI. Meta-analysis of the whole-blood gene expression data resulted in the identification of 3762 annotated genes whose transcript levels were significantly associated with BMI after adjusting for multiple testing [Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.01] (Additional file 2: Table S1). Recently, the Data-driven Expression Prioritized Integration for Complex Traits (DEPICT) method was used to prioritize BMI-related genes [5]. Of the 989 genes prioritized by DEPICT as BMI-related, 388 exhibited significant mRNA levels in our analysis. For 151 of these transcripts, we could confirm association of the their expression levels with BMI (Additional file 2: Table S33). Of the 3762 genes described above, the correlation between mRNA abundance and BMI was positive for 1269 genes (33.7 %) and negative for 2411 genes (64.1 %), while 82 genes (2.2 %) exhibited inconsistent effect directions on the probe level. In the latter case, the different probes target different exons of the corresponding genes, indicating that individual mRNA isoforms specified by the same genes were inversely associated with BMI. Adjustment for HOMA-IR resulted in the detection of 1836 and 2602 transcripts exhibiting positive and negative BMI-correlations, respectively, with an overlap of 90.2 % and 94.1 % to the non-HOMA-IR-adjusted analysis, demonstrating that associations of BMI with transcript levels were largely independent of HOMA-IR (Additional file 2: Table S34). Using Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA) software, we identified 128 and 63 canonical pathways exhibiting significant association with BMI after controlling the FDR at 0.05 and 0.01, respectively (Additional file 2: Table S5). In order to validate robustness across platforms, the pathway over-representation analysis was repeated using the web-based toolkit WebGestalt (bioinfo.vanderbilt.edu/webgestalt/) and the online database resources KEGG (genome.jp/kegg/) and WikiPathways (wikipathways.org). The significantly enriched pathways were essentially concordant with those detected using IPA (Additional files 3 and 4). Subsequent closer inspection of the assigned gene-specific transcripts revealed a strong overlap between the gene/protein content of numerous of the canonical IPA-pathways. The extensive connectivity of the nodes displayed in Fig. 1 represents this strong overlap among the pathways, particularly for the attenuated insulin signaling. We therefore restricted the interpretation of the pathway analysis to the top 25 IPA-pathways exhibiting the most significant associations and defined three prominent whole-blood gene expression signatures (see below) as the major outcome of the analysis.

Table 1.

Cohort characteristics

| Variables | SHIP-TREND | KORA F4 |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age [years] | 50.1 ± 13.7 | 70.4 ± 5.4 |

| Females | 555 (56.0 %) | 493 (49.6 %) |

| Active smokers | 214 (21.2 %) | 66 (6.7 %) |

| Mean body height [cm] | 169.8 ± 9.0 | 165.3 ± 8.8 |

| Body weight [kg] | 79.0 ± 15.1 | 78.9 ± 13.7 |

| Body mass index (BMI) [kg/m2] | 27.3 ± 4.6 | 28.9 ± 4.5 |

| Waist circumference [cm] | 88.0 ± 12.9 | 98.6 ± 12.1 |

| Waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) | 0.87 ± 0.09 | 0.91 ± 0.08 |

| Fasting glucose [mg/dL] | 97.9 ± 11.2 | 104.8 ± 22.8 |

| 2-hour glucose OGTT [mg/dL] | 117.3 ± 36.7 | 128.7 ± 42.4 |

| Fasting insulin [mU/L] | 6.7 ± 8.3 | 10.4 ± 33.5 |

| Homeostasis model assessment insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) | 1.15 ± 1.72 | 2.82 ± 8.95 |

| HbA1c [%] | 5.19 ± 0.57 | 5.77 ± 0.69 |

| Leptin [ng/mL] | 15.6 ± 14.5 | 22.4 ± 24.3 |

| Red blood cell count [Tpt/L] | 4.63 ± 0.39 | 4.50 ± 0.40 |

| White blood cell count [pt/nl] | 5.72 ± 1.48 | 6.00 ± 1.81 |

| Platelet count [pt/nl] | 225.7 ± 50.3 | 244.7 ± 65.1 |

| Hematocrit [l/l] | 0.42 ± 0.03 | 0.41 ± 0.03 |

| Systolic blood pressure (SBP) [mmHg] | 124.4 ± 16.9 | 128.7 ± 20.0 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (DBP) [mmHg] | 76.6 ± 9.8 | 74.0 ± 10.1 |

Data are given as mean ± standard deviation or as number and percent (in parentheses). OGTT oral glucose tolerance test, Tpt/L 1012 cells/L

Fig. 1.

Overlap graph of the top 25 enriched IPA-pathways. Each node represents one pathway significantly enriched with BMI-associated gene-specific transcripts. The node size is proportional to the number of BMI-associated transcripts within each respective pathway. Edge shade and width refer to the overlap between pathways in terms of shared transcripts and were calculated based on the Jaccard similarity coefficient, which is defined as the size of the intersection divided by the size of the union of two sample sets. Edges between nodes are shown if transcripts are shared between pathways and if the Jaccard coefficient ≥ 90th percentile. Nodes, i.e., pathways are colored according to the three defined gene expression signatures. The extensive connectivity, particularly for the attenuated insulin signaling, represents the strong overlap among the pathways. Pathways are numbered according to their enrichment p-values. 1: EIF2 Signaling, 2: Mitochondrial Dysfunction, 3: Regulation of eIF4 and p70S6K Signaling, 4: PI3K/AKT Signaling, 5: Insulin Receptor Signaling, 6: Hypoxia Signaling in the Cardiovascular System, 7: Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Signaling, 8: Production of Nitric Oxide and Reactive Oxygen Species in Macrophages, 9: Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Signaling, 10: ILK Signaling, 11: AMPK Signaling, 12: JAK/Stat Signaling, 13: Renal Cell Carcinoma Signaling, 14: NRF2-mediated Oxidative Stress Response, 15: Ceramide Signaling, 16: mTOR Signaling, 17: CTLA4 Signaling in Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes, 18: B Cell Receptor Signaling, 19: Prostate Cancer Signaling, 20: Glioma Signaling, 21: Oxidative Phosphorylation, 22: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Signaling, 23: Heme Biosynthesis II, 24: Cyclins and Cell Cycle Regulation, 25: PDGF Signaling

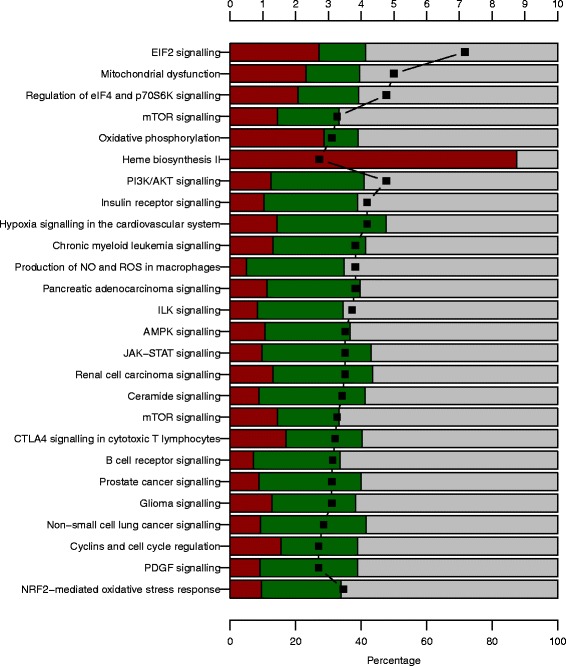

The 25 pathways included EIF2 Signaling, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Regulation of eIF4 and p70S6K Signaling, PI3K/AKT Signaling, Insulin Receptor Signaling, Hypoxia Signaling in the Cardiovascular System, Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Signaling, Production of Nitric Oxide and Reactive Oxygen Species in Macrophages, Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Signaling, ILK Signaling, AMPK Signaling, JAK/Stat Signaling, Renal Cell Carcinoma Signaling, NRF2-mediated Oxidative Stress Response, Ceramide Signaling, mTOR Signaling, CTLA4 Signaling in Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes, B Cell Receptor Signaling, Prostate Cancer Signaling, Glioma Signaling, Oxidative Phosphorylation, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Signaling, Heme Biosynthesis II, Cyclins and Cell Cycle Regulation, and PDGF Signaling (Fig. 2 and Table 2). These 25 pathways comprised 396 genes whose transcript abundance in whole-blood was significantly associated with BMI (Additional file 2: Tables S4–S30). Overall, the correlations were positive for 171 genes (43.2 %) and negative for 225 genes (56.8 %). Permutation analysis confirmed over-representation of genes in all pathways but PDGF Signaling (for details see Additional file 1: Supplementary Materials).

Fig. 2.

Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) results. The results are shown for the 25 most significantly enriched BMI-associated canonical IPA pathways. The percentage of transcripts that are positively, negatively or not significantly associated with BMI in the meta-analysis is provided as red, green and grey bars, respectively. Black squares display the –log10 p-value

Table 2.

The 25 IPA-pathways most significantly enriched for BMI-associated gene-specific transcripts in the SHIP-TREND/KORA F4 meta-analysis

| Defined gene expression signatures with assigned canonical IPA-pathways | FDR for genes with BMI-associated mRNA levels (all genes/ positively associated/ negatively associated) | Number of genes with BMI-associated mRNA levels (all genes/ positively associated/ negatively associated) | FDR from permutation analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erythrocyte-Reticulocyte Ratio Shift | |||

| EIF2 signaling | 6.8 × 10 -8/ 6.3 × 10 -14/ 5.8 × 10-1 | 70/ 46/ 24 | 0.0002 |

| Mitochondrial dysfunction | 1.0 × 10 -5/ 3.6 × 10 -8/ 3.2 × 10-1 | 58/ 34/ 24 | 0.0002 |

| Regulation of eIF4 and p70S6K signaling | 1.7 × 10 -5/ 4.5 × 10 -6/ 1.3 × 10-1 | 55/ 29/ 26 | 0.0002 |

| mTOR signaling | 5.4 × 10 -4/ 1.1 × 10-2/ 6.9 × 10-2 | 60/ 26/ 34 | 0.0059 |

| Oxidative phosphorylation | 7.9 × 10 -4/ 4.9 × 10 -8/ N. A. | 34/ 25/ 9 | 0.0002 |

| Heme biosynthesis II | 1.9 × 10 -3/ 4.5 × 10 -6/ N. A. | 7/ 7/ 0 | 0.0002 |

| Attenuated Insulin Signaling | |||

| PI3K/AKT signaling | 1.7 × 10 -5/ 3.6 × 10-1/ 6.9 × 10 -4 | 49/ 15/ 34 | 0.0002 |

| Insulin receptor signaling | 6.5 × 10 -5/ 8.6 × 10-1/ 5.8 × 10 -4 | 49/ 13/ 36 | 0.0002 |

| Hypoxia signaling in the cardiovascular system | 6.5 × 10 -5/ 4.5 × 10-1/ 6.9 × 10 -4 | 30/ 9/ 21 | 0.0002 |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia signaling | 1.5 × 10 -4/ 4.5 × 10-1/ 1.7 × 10 -3 | 38/ 12/ 26 | 0.0002 |

| Production of NO and ROS in macrophages | 1.5 × 10 -4/ N. A./ 4.3 × 10 -6 | 62/ 9/ 53 | 0.0002 |

| Pancreatic adenocarcinoma signaling | 1.5 × 10 -4/ 7.6 × 10-1/ 7.4 × 10 -4 | 42/ 12/ 30 | 0.0134 |

| ILK signaling | 1.9 × 10 -4/ 8.8 × 10-1/ 5.8 × 10 -4 | 62/ 15/ 47 | 0.0002 |

| AMPK signaling | 3.1 × 10 -4/ 7.7 × 10-1/ 1.6 × 10 -3 | 48/ 14/ 34 | 0.0026 |

| JAK-STAT signaling | 3.1 × 10 -4/ 8.8 × 10-1/ 6.9 × 10 -4 | 31/ 7/ 24 | 0.0154 |

| Renal cell carcinoma signaling | 3.1 × 10 -4/ 6.8 × 10-1/ 2.1 × 10 -3 | 30/ 9/ 21 | 0.0170 |

| Ceramide signaling | 3.8 × 10 -4/ 9.2 × 10-1/ 6.9 × 10 -4 | 33/ 7/ 26 | 0.0026 |

| mTOR signaling | 5.4 × 10 -4/ 1.1 × 10-2/ 6.9 × 10-2 | 60/ 26/ 34 | 0.0059 |

| CTLA4 signaling in cytotoxic T lymphocytes | 6.2 × 10 -4/ 5.0 × 10-2/ 3.8 × 10-2 | 33/ 14/ 19 | 0.0002 |

| B cell receptor signaling | 7.4 × 10 -4/ 9.2 × 10-1/ 5.8 × 10 -4 | 56/ 12/ 44 | 0.0002 |

| Prostate cancer signaling | 7.9 × 10 -4/ 9.2 × 10-1 / 8.5 × 10 -4 | 32/ 7/ 25 | 0.0002 |

| Glioma signaling | 7.9 × 10 -4/ 4.5 × 10-1/ 7.6 × 10 -3 | 36/ 12/ 24 | 0.0085 |

| Non-small cell lung cancer signaling | 1.4 × 10 -3/ 9.2 × 10-1/ 1.5 × 10 -3 | 27/ 6/ 21 | 0.0002 |

| Cyclins and cell cycle regulation | 2.0 × 10 -3/ 1.9 × 10-1/ 4.1 × 10-2 | 30/ 12/ 18 | 0.0002 |

| PDGF signaling | 2.0 × 10 -3/ 9.0 × 10-1/ 1.7 × 10 -3 | 30/ 7/ 23 | 0.1620 |

| Reduced Protection against Oxidative Stress | |||

| NRF2-mediated oxidative stress response | 3.5 × 10 -5/ 8.7 × 10-1/ 8.5 × 10 -4 | 60/ 17/ 43 | 0.0489 |

The pathway “mTOR Signaling” is assigned to two signatures: “Erythrocyte-Reticulocyte Ratio Shift” (positively associated transcripts) and “Attenuated Insulin Signaling” (negatively associated transcripts). Benjamini-Hochberg-FDR-values < 0.01 are provided in bold. Permutation analysis was performed to evaluate robustness of the pathway enrichment. The single Benjamini- Hochberg corrected p-value > 0.05 possibly indicating a false positive result (PDGF signaling) is underlined

A gene expression signature indicating a ratio shift from mature erythrocytes towards reticulocytes

A large part of the 171 positively correlated gene-specific transcripts in the top 25 IPA-pathways specified components of the cellular protein synthesis apparatus (ribosomal proteins and translation factors) and mitochondrial proteins, in particular of the respiratory chain and the F0/F1 ATP synthase complex. This was mainly the case for the pathways EIF2 signaling, Mitochondrial dysfunction, Oxidative phosphorylation, Regulation of eIF4 and p70S6K signaling, and mTOR signaling (Fig. 2 and Table 2). Expression of these genes is strongly induced by pro-proliferative signals and mainly driven by the transcription factor MYC [13, 14]. The BMI-associated increase in the abundance of these transcripts most probably reflected a ratio shift from mature erythrocytes that contain only mRNA remnants [15] towards reticulocytes with substantial mRNA content. The number of bone marrow-residing adipocytes increases with BMI and adipocyte-secreted leptin promotes hematopoiesis and lymphopoiesis [16–18]. Thus, positive correlations were described between both red and white blood cell counts on the one hand and BMI/obesity as well as pre-diabetes/T2D [19, 20] on the other hand. In line with these findings, we observed significant positive correlations of serum leptin, fasting glucose, and 2 h-OGTT glucose with BMI in our study (p = 4.27 × 10−245, 1.23 × 10−27, and 3.25 × 10−27, respectively). Concurrently, erythrocyte survival decreases with increasing BMI and higher blood glucose concentration [21, 22], most probably due to pronounced oxidative stress [23]. Thus, the positive correlations between BMI and mRNA abundances of MYC-regulated genes of the EIF2 signaling, Mitochondrial dysfunction, Oxidative phosphorylation, Regulation of eIF4 and p70S6K signaling, and mTOR signaling are rather attributable to a shift in the erythrocyte/reticulocyte ratio than being a consequence of altered gene regulation, which might also be the case for many other positively correlated transcripts. This interpretation is strengthened by our observation that mRNA abundances of all seven genes of the Heme biosynthesis II pathway, which are highly expressed in reticulocytes, were also positively correlated with BMI (Additional file 2: Table S28).

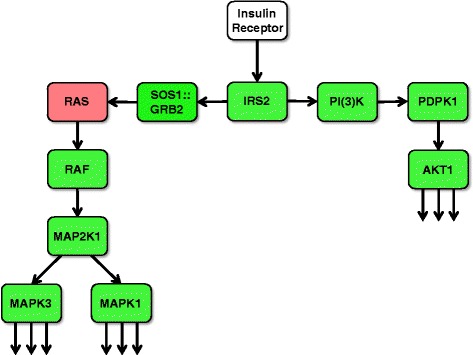

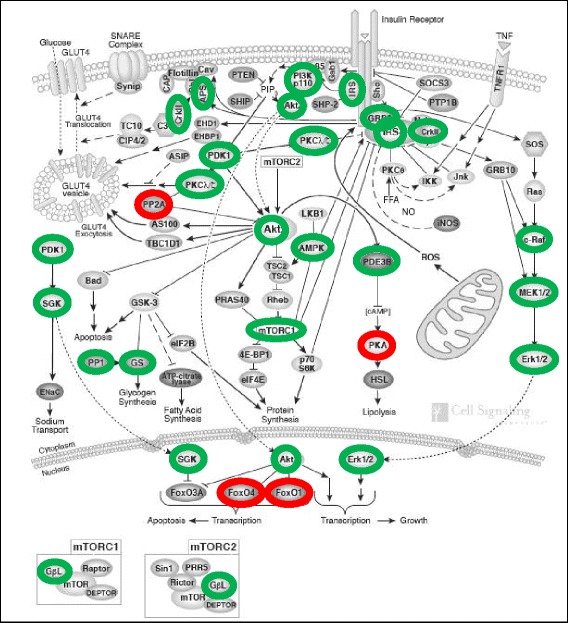

A gene expression signature indicating decreased expression of genes essentially involved in transmission and amplification of the insulin signal

The majority of gene-specific transcripts of the other 20 pathways which share a large number of genes (Fig. 1) were negatively correlated with BMI. Strikingly, five genes (IRS2, PIK3CD, PIK3R4, PDPK1, AKT1) encoding key proteins involved in AKT-dependent transduction of the insulin signal exhibited decreased mRNA abundances with increasing BMI (Fig. 3; for details see Additional file 1: Supplementary Materials S1). Besides the AKT-linked signal transduction cascade, the insulin signal is also transmitted by the SOS1::GRB2-RAS-RAF-MEK axis. This pathway primarily mediates the initiation of mRNA translation as well as of transcriptional responses (Fig. 3; for details see see Additional file 1: Supplementary Materials S1). Five genes (GRB2, RAF1, MAP2K1, MAPK3, MAPK1) encoding key proteins of this latter signaling axis showed decreased mRNA levels with increasing BMI. Regulation of the genes of these two main insulin signaling pathways is particularly important as strong amplification of the primary insulin signal occurs during these initial transmission steps. Furthermore, 26 additional genes involved in insulin signaling downstream of the main axes exhibited reduced mRNA abundances with increasing BMI. These expression changes could also contribute to or at least indicate attenuated signaling. In contrast, BMI-transcript correlations indicating improved signaling could only be detected for five additional genes (for details see Fig. 4 and Additional file 1: Supplementary Materials S1).

Fig. 3.

BMI-associated net down-regulation of the two main signal transduction axes propagating and amplifying the initial insulin signal. Ligand-activated insulin receptor mediates activating tyrosine phosphorylation of IRS (insulin receptor substrate) proteins. Downstream of IRS, there are two major signal transduction branches: The PI(3)K → PDPK1 → AKT (right) and the SOS1::GRB2 → RAS → RAF → AP2K1 (MEK family) → MAPK3/MAPK1 (ERK family) kinase cascades (left). Tyrosine-phosphorylated IRS proteins bind PI(3)K and the SOS1::GRB2 complex. The activated SOS1::GRB2 complex promotes GDP-GTP exchange on p21ras (RAS), thereby activating the RAS → RAF → MAP2K1 (MEK family) → MAPK3/MAPK1 (ERK family) branch. Activation of PI(3)K (phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphosphate 3–kinase) by IRS causes the production of PI3,4P2 (phosphatidylinositol-3, 4-bisphosphate) and PI3,4,5P3 (phosphatidylinositol-3, 4,5-triphosphate) which recruit PDPK1 (3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1) and AKT proteins to the membrane. Subsequently, AKT is activated by PDPK1-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation. Finally, AKT and the ERK family kinases phosphorylate numerous cellular substrate proteins, resulting in their activation or inactivation (for details see Additional file 1: Supplementary Materials S1). Green and red coloring indicates signal transduction modules with corresponding mRNA levels that are negatively and positively correlated, respectively, with BMI in the present study

Fig. 4.

Attenuation of insulin signaling under conditions of increased BMI as derived from the mRNA abundances as determined in the present study. Green and red coloring indicates negative and positive correlation of the gene-specific transcripts specifying the corresponding proteins/protein complexes shown here with BMI. Labeled are those insulin signaling modules whose decrease or increase on the protein level is predicted to contribute to or to be indicative of attenuated transduction of the insulin signal. Illustration adopted and modified by courtesy of Cell Signaling Technology/New England Biolabs

We further observed positive correlations between FOXO3 or FOXO4 mRNA abundances and BMI. Both genes encode prominent transcription factors involved in glucose homoeostasis. As a consequence of decreased AKT-dependent phosphorylation, increased amounts of FOXO proteins translocate to the nucleus where they drive the expression of their own genes in a positive feedback loop. This mechanism may explain the positive correlation of FOXO3 or FOXO4 transcript levels with BMI.

The mRNA signature of attenuated insulin signaling suggests that high BMI may cause lower amounts of key proteins involved in transduction and amplification of the insulin signal, pointing to a plausible mechanism contributing to the well-established association between obesity and insulin resistance. In line with these findings, we also found positive correlations between BMI and fasting glucose (p = 1.23 × 10−27), 2 h-OGTT glucose (p = 3.25 × 10−27), blood insulin (p = 1.11 × 10−14) as well as HOMA-IR (p = 3.95 × 10−18), confirming the link between increased BMI/obesity and insulin resistance or (pre)diabetes, respectively. The demonstration of attenuated insulin signaling processes in easily accessible whole-blood samples was surprising as blood cells do not belong to the classical insulin-sensitive tissues primarily involved in glucose homoeostasis, such as liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue.

A gene expression signature indicating reduced expression of key genes involved in the defence against reactive oxygen species (ROS)

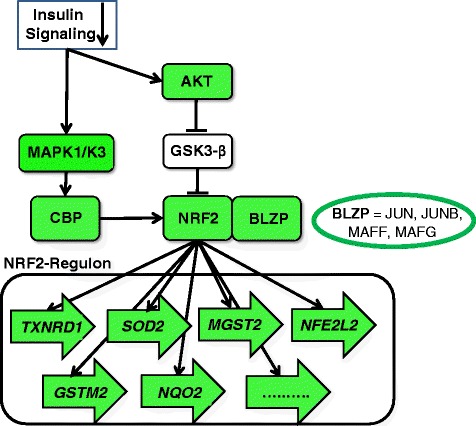

The pathomechanisms underlying vascular and non-vascular complications related to insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and T2D have not been completely resolved yet. Recent epidemiological evidence suggests a central role of oxidative stress [24, 25]. In our analyses, the transcript levels of multiple prominent target genes of NRF2, the key regulatory transcription factor of the major cellular defense system against oxidative stress, were negatively correlated with BMI (Fig. 5; for details see Additional file 1: Supplementary Materials S3). Consistent with this finding, mRNA levels of four genes encoding direct NRF2 dimerization partners and of CREBBP encoding a nuclear trans-activator of NRF2 were also negatively correlated with BMI (Fig. 5). Furthermore, full activation of NRF2 requires insulin signaling via the AKT- and ERK-mediated phosphorylation cascades, which are predicted to be attenuated with increasing BMI. Together these results indicate that the most important cellular defense system against oxidative stress becomes progressively impaired with increasing BMI, which is in agreement with the aforementioned epidemiological associations.

Fig. 5.

BMI-associated down-regulation of the NRF2 regulon. The transcription factor NRF2, after translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, binds to the cis-acting enhancer sequence ARE (Antioxidant Response Element) located in promoters upstream of several genes encoding proteins necessary for glutathione synthesis and electrophile detoxification (for details see Additional file 1: Supplementary Materials S3). Transcriptional activation of ARE-mediated genes requires hetero-dimerization of NRF2 with other basic leucine zipper proteins (BLZP), namely JUN (c-JUN, JUN-D and JUN-B) and the small musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma (MAF) proteins (MAFG, MAFK and MAFF). In addition, the CREBBP encoded CBP protein [cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB) binding protein], a histone acetyl transferase, represents a nuclear co-activator directly trans-activating NRF2. Among the prominent ARE-mediated NRF2 targets genes are GSTM2 and MGST2 encoding the glutathione S-transferases μ2 and microsomal glutathione S-transferase 2, respectively, the NQO2-encoded NAD(P)H:quinone acceptor oxidoreductase 2, the SOD2-encoded manganese-containing superoxide dismutase 2 (MnSOD), and the TXNRD1-encoded thioredoxin reductase 1. In addition, the NRF2 encoding gene NFE2L2 contains two ARE-like sequences in its promoter and is therefore auto-regulated by NRF2 in a positive feedback-loop. Green coloring indicates that the corresponding mRNA abundances were negatively correlated with BMI in the present study. Arrows indicate ARE-regulated genes

Conclusions

Here, we demonstrate extensive BMI-associated alterations of the whole-blood transcriptome with more than 3,500 transcripts exhibiting positive or negative BMI-correlation. Of particular interest, we report the identification of three distinct gene expression signatures associated with increased BMI in a meta-analysis of array-based whole-blood transcriptome profiling data of 1977 individuals from two large population-based cohorts. These signatures reflect (1) a ratio shift from mature erythrocytes towards reticulocytes, (2) impaired insulin signaling, and (3) impaired defense against oxidative stress. The latter two signatures corroborate and augment epidemiological findings and emphasize the value of whole-blood gene expression profiling for the analysis of molecular mechanisms underlying complex traits and diseases. Comparing the correlations between detected transcripts and BMI with the correlations between transcripts and five further phenotypes of relevance in the context BMI/ insulin resistance revealed pronounced overlaps in the order of decreasing similarity: BMI > serum leptin > 2 h-OGTT glucose > fasting glucose > blood insulin > HOMA-IR. This was consistent for all three expression signatures found in our analyses (Additional file 5: Figure S1). As circadian rhythms in whole-blood gene expression patterns have been described [26], it has to be emphasized that in SHIP-TREND as well in KORA F4 all blood samples were collected between 8 a.m. and noon from fasting individuals. Considerable bias of our results due to circadian blood cell gene expression variation is thus unlikely.

The mechanisms underlying the extensive BMI-associated down-regulation of several key genes involved in insulin signaling and defense against oxidative stress on the mRNA level are currently unclear. Interestingly, several micro-RNAs (miRNAs) have been found to be differentially expressed in tissues relevant for insulin signaling and resistance (liver, skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, and pancreatic beta cells) during obesity, hyperglycemia, and diabetes (for details see see Additional file 1: Supplementary Materials S4). It is conceivable that the BMI-associated down-regulation of many genes may be mediated by specific miRNAs.

One limitation of this study is the fact that it is exclusively based on gene expression profiles obtained from whole-blood cell analyses in a cross-sectional design. The data indicating attenuated insulin signaling and decreased resistance against oxidative stress might not directly translate to other tissues more relevant for insulin signaling such as liver, skeletal muscle and adipose tissue. Although our results already have gained some support by observations in animal models [27, 28], appropriate functional analyses are needed to reveal the details of the molecular mechanisms involved. A further limitation consists in the fact that the observed BMI-associated mRNA level alterations represent two co-occurring phenomena, specific gene expression changes on the one hand but also the described erythrocyte-reticulocyte shift on the other hand. Due to the fact that reticulocyte counts were determined neither in SHIP nor in KORA, an appropriate adjustment was not possible. Therefore, the interference of both BMI-dependent effects, namely the decreased amounts of specific mRNAs due to reduced gene expression and the increased amounts of other mRNAs due to a higher reticulocyte number, may explain seemingly contradictory observations, which can be illustrated using NRF2-regulated genes as an example. Although nearly all genes encoding NRF2 key regulators (including the structural gene of the transcription factor itself, NFE2L2) as well as some of the most prominent NRF2 targets exhibited a negative mRNA correlation with BMI, some other target gene transcripts were positively correlated. These latter genes might be particularly strongly expressed in reticulocytes, overriding their down-regulation in leukocytes. A generalization of this assumption would imply that the effect strengths of other observed negative correlations between BMI and transcripts, as those observed for the genes encoding insulin signaling key proteins, might be even more pronounced in isolated leukocytes, in particular neutrophil granulocytes, as these represent the predominant white cell fraction in whole-blood. Therefore, while a transcriptome analysis of isolated granulocyte fractions would be most desirable in future studies addressing associations between BMI and gene expression, whole-blood expression patterns are also of value but likely underestimate the true expression changes occurring in different white blood cell populations, including granulocytes. It also has to be mentioned that with a mean age of 50 and 70 years in KORA and SHIP, respectively, these cohorts are relatively old and thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that at least partially differing results would be obtained with clearly younger individuals. As the relationship between obesity and mortality changes with increasing age, the identified gene expression signatures, in particular those related to insulin signaling and oxidative stress defense, might also be affected in a younger cohort. Finally, we would like to emphasize the fact that the three extracted signatures are based on a subset of around 400 from the more than 3700 BMI-associated gene-specific transcripts annotated in IPA. This demonstrates that for most of the BMI-associated whole-blood transcriptome, adequate physiological interpretation is still not available. Further hypotheses about the mechanisms underlying the observed associations might be generated by using more sophisticated bioinformatical approaches in future analyses.

Availability of supporting data

The KORA F4 whole-blood transcriptome raw data are deposited in the ArrayExpress Archive of Functional Genomics Data (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/) with the accession number E-MTAB-1708. The SHIP-TREND whole-blood transcriptome raw data are deposited in the GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus) public functional genomics data repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) with the GEO series accession number GSE36382.

Additional files

Supplementary Materials: Supplementary Text: Supplementary information about relevant pathways and genes. Supplementary References. Legend for supplementary Figure. (DOC 315 kb)

Results of the SHIP-TREND/KORA F4 meta-analysis with p (BH) < 0.01 (z-score based p-value). Table S2. Number of probes indicating significantly BMI-associated expression in the SHIP-TREND/KORA F4 meta-analysis. Table S3. Number of genes exhibiting significantly BMI-associated expression in the SHIP-TREND/KORA F4 meta-analysis. Table S4. Genes exhibiting BMI-associated mRNA abundances and are assigned to the 25 most significantly BMI-associated canonical IPA-pathways detected in this study. Table S5. BMI-associated pathways with p (BH) < 0.05. Tables S6-S30. Genes exhibiting BMI-associated mRNA abundances and are assigned to the canonical IPA-pathways listed in Table 2. Table S31. Annotation of all 48,803 Illumina HumanHT-12 v3 probes and respective detection rates (Illumina’s detection p-value < 0.05) in SHIP-TREND and KORA F4. Table S32. Meta-analysis results for the main model with and without adjustment for HOMA-IR for all 12,778 Illumina probes indicating significant transcript levels in SHIP-TREND and KORA F4. Table S33. Association results for the detected genes priorized using the DEPICT method and described in Locke et al. [5]. Table S34. Results of sensitivity analyses in KORA F4 - additional adjustment for HOMA-IR or type 2 diabetes status. (XLSX 18052 kb)

Supplementary Table KEGG_pathways_WebGestalt: Results of the pathway over-representation analysis using the web-based toolkit WebGestalt ( bioinfo.vanderbilt.edu/webgestalt/ ) and the online database resource KEGG ( genome.jp/kegg/ ). (XLS 46 kb)

Supplementary Table WikiPathways_pathways_WebGestalt: Results of the pathway over-representation analysis using the web-based toolkit WebGestalt ( bioinfo.vanderbilt.edu/webgestalt/ ) and the online database resource WikiPathways ( wikipathways.org ). (XLS 39 kb)

Correlation of Signature Transcripts with BMI-related Traits. (PDF 39 kb)

Acknowledgments

SHIP-TREND: SHIP is supported by the BMBF (German Ministry of Education and Research) and by the DZHK (Deutsches Zentrum für Herz-Kreislauf-Forschung – German Centre for Cardiovascular Research). SHIP is part of the Community Medicine Research net of the University of Greifswald, Germany, which is funded by BMBF (grants no. 01ZZ9603, 01ZZ0103, and 01ZZ0403), the Ministry of Cultural Affairs as well as the Social Ministry of the Federal State of Mecklenburg-West Pomerania, and the network ‘Greifswald Approach to Individualized Medicine (GANI_MED)’ funded by the BMBF (grant 03IS2061A). Generation of genome-wide data has been supported by the BMBF (grant no. 03ZIK012) and phenotypic analysis was supported by the BMBF Competence Network Obesity. The body map data was kindly provided by the Gene Expression Applications research group at Illumina.

KORA F4: The KORA authors acknowledge the contributions of Peter Lichtner, Gertrud Eckstein, Guido Fischer, Norman Klopp, Nicole Spada, and all members of the Helmholtz Zentrum München genotyping staff for generating the SNP data and Katja Junghans and Anne Löschner (Helmholtz Zentrum München) for generating gene expression data from both KORA and SHIP-TREND samples. The KORA study was initiated and financed by the Helmholtz Zentrum München – German Research Center for Environmental Health, which is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and by the State of Bavaria. Furthermore, KORA research was supported within the Munich Center of Health Sciences (MC-Health), Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, as part of LMUinnovativ. We thank the field staff in Augsburg who was involved in the studies. This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Research of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia (MIWF NRW) and the German Federal Ministry of Health (BMG). The Diabetes Cohort Study was funded by a German Research Foundation project grant to WR (DFG; RA 459/2-1). This study was supported in part by a grant from the BMBF to the German Center for Diabetes Research (DZD e.V.), by the DZHK (Deutsches Zentrum für Herz-Kreislauf-Forschung – German Centre for Cardiovascular Research) and by the BMBF-funded Systems Biology of Metabotypes grant SysMBo#0315494A). Additional support was given by the BMBF (National Genome Research Network NGFNplus 01GS0834 and 01GS0823) and the Leibniz Association (WGL Pakt für Forschung und Innovation). We thank Gabi Gornitzka and Astrid Hoffmann (German Diabetes Center) for excellent technical assistance.

We thank all study participants, volunteers and study personnel that made this work possible.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- FDR

Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate

- GWAS

Genome-wide association study

- HOMA-IR

Homeostasis model assessment – insulin resistance

- KORA

Kooperative Gesundheitsforschung in der Region Augsburg (Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg)

- RBC

Red blood cell count

- RIN

RNA integrity number

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SHIP

Study of Health in Pomerania

- T2D

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TWAS

Transcriptome-wide association study

- WBC

White blood cell count

Footnotes

Georg Homuth, Simone Wahl, Christian Müller, Claudia Schurmann, Uwe Völker, Holger Prokisch and Tanja Zeller contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SB, SBF, GH, TM, HP, UV, and TZ initiated and designed the study. MC, CE, HG, CH, TI, AM, CSM, MN, AP, HP, ER, MR, WR, KS, LS, HV, HW, PSW, and TZ were involved in data acquisition. MD, KE, CG, GH, JK, CM, UM, RR, AS, CS, AT, SW, AZ, and TZ performed the data analysis and interpretation. CH, GH, CM, JM, RR, CS, UV, HW, and SW wrote the manuscript. The manuscript has been revised and approved by all other authors.

Contributor Information

Georg Homuth, Email: georg.homuth@uni-greifswald.de.

Simone Wahl, Email: simone.wahl@helmholtz-muenchen.de.

Christian Müller, Email: christian_m@gmx.net.

Claudia Schurmann, Email: claudia.schurmann@mssm.edu.

Ulrike Mäder, Email: ulrike.maeder@uni-greifswald.de.

Stefan Blankenberg, Email: s.blankenberg@uke.de.

Maren Carstensen, Email: maren.carstensen@ddz.uni-duesseldorf.de.

Marcus Dörr, Email: mdoerr@uni-greifswald.de.

Karlhans Endlich, Email: karlhans.endlich@uni-greifswald.de.

Christian Englbrecht, Email: che74@gmx.de.

Stephan B. Felix, Email: felix@uni-greifswald.de

Christian Gieger, Email: christian.gieger@helmholtz-muenchen.de.

Harald Grallert, Email: harald.grallert@helmholtz-muenchen.de.

Christian Herder, Email: Christian.Herder@ddz.uni-duesseldorf.de.

Thomas Illig, Email: Illig.Thomas@mh-hannover.de.

Jochen Kruppa, Email: Jochen.Kruppa@med.uni-goettingen.de.

Carola S. Marzi, Email: carola.marzi@helmholtz-muenchen.de

Julia Mayerle, Email: mayerle@uni-greifswald.de.

Thomas Meitinger, Email: Meitinger@helmholtz-muenchen.de.

Andres Metspalu, Email: andres.metspalu@ut.ee.

Matthias Nauck, Email: matthias.nauck@uni-greifswald.de.

Annette Peters, Email: peters@helmholtz-muenchen.de.

Wolfgang Rathmann, Email: rathmann@ddz.uni-duesseldorf.de.

Eva Reinmaa, Email: eva.reinmaa@ut.ee.

Rainer Rettig, Email: rettig@uni-greifswald.de.

Michael Roden, Email: Michael.Roden@ddz.uni-duesseldorf.de.

Arne Schillert, Email: arne.schillert@imbs.uni-luebeck.de.

Katharina Schramm, Email: katharina.schramm@helmholtz-muenchen.de.

Leif Steil, Email: steil@uni-greifswald.de.

Konstantin Strauch, Email: strauch@helmholtz-muenchen.de.

Alexander Teumer, Email: ateumer@uni-greifswald.de.

Henry Völzke, Email: voelzke@uni-greifswald.de.

Henri Wallaschofski, Email: henri.wallaschofski@hotmail.com.

Philipp S. Wild, Email: philipp.wild@unimedizin-mainz.de

Andreas Ziegler, Email: ziegler@imbs.uni-luebeck.de.

Uwe Völker, Email: voelker@uni-greifswald.de.

Holger Prokisch, Email: Prokisch@helmholtz-muenchen.de.

Tanja Zeller, Email: t.zeller@uke.de.

References

- 1.Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, Dietz WH, Vinicor F, Bales VS, Marks JS. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA. 2003;289(1):76–79. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pischon T, Boeing H, Hoffmann K, Bergmann M, Schulze MB, Overvad K, van der Schouw YT, Spencer E, Moons KG, Tjonneland A, et al. General and abdominal adiposity and risk of death in Europe. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(20):2105–2120. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vimaleswaran KS, Loos RJ. Progress in the genetics of common obesity and type 2 diabetes. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2010;12 doi: 10.1017/S1462399410001389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walley AJ, Asher JE, Froguel P. The genetic contribution to non-syndromic human obesity. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(7):431–442. doi: 10.1038/nrg2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI, Justice AE, Pers TH, Day FR, Powell C, Vedantam S, Buchkovich ML, Yang J, et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature. 2015;518(7538):197–206. doi: 10.1038/nature14177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dermitzakis ET. From gene expression to disease risk. Nat Genet. 2008;40(5):492–493. doi: 10.1038/ng0508-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghosh S, Dent R, Harper ME, Gorman SA, Stuart JS, McPherson R. Gene expression profiling in whole blood identifies distinct biological pathways associated with obesity. BMC Med Genomics. 2010;3:56. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-3-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rathmann W, Haastert B, Icks A, Lowel H, Meisinger C, Holle R, Giani G. High prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes mellitus in Southern Germany: target populations for efficient screening. The KORA survey. Diabetologia 2003. 2000;46(2):182–189. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-1025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holle R, Happich M, Lowel H, Wichmann HE, Group MKS. KORA--a research platform for population based health research. Gesundheitswesen. 2005;67(Suppl 1):S19–S25. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-858235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rathmann W, Strassburger K, Heier M, Holle R, Thorand B, Giani G, Meisinger C. Incidence of Type 2 diabetes in the elderly German population and the effect of clinical and lifestyle risk factors: KORA S4/F4 cohort study. Diabetic medicine : a journal of the British Diabetic Association. 2009;26(12):1212–1219. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Volzke H, Alte D, Schmidt CO, Radke D, Lorbeer R, Friedrich N, Aumann N, Lau K, Piontek M, Born G, et al. Cohort profile: the study of health in Pomerania. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(2):294–307. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schurmann C, Heim K, Schillert A, Blankenberg S, Carstensen M, Dorr M, Endlich K, Felix SB, Gieger C, Grallert H, et al. Analyzing illumina gene expression microarray data from different tissues: methodological aspects of data analysis in the metaxpress consortium. PLoS One. 2012;7(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Riggelen J, Yetil A, Felsher DW. MYC as a regulator of ribosome biogenesis and protein synthesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(4):301–309. doi: 10.1038/nrc2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li F, Wang Y, Zeller KI, Potter JJ, Wonsey DR, O’Donnell KA, Kim JW, Yustein JT, Lee LA, Dang CV. Myc stimulates nuclearly encoded mitochondrial genes and mitochondrial biogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(14):6225–6234. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.6225-6234.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goh SH, Josleyn M, Lee YT, Danner RL, Gherman RB, Cam MC, Miller JL. The human reticulocyte transcriptome. Physiol Genomics. 2007;30(2):172–178. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00247.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trottier MD, Naaz A, Li Y, Fraker PJ. Enhancement of hematopoiesis and lymphopoiesis in diet-induced obese mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(20):7622–7629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205129109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mikhail AA, Beck EX, Shafer A, Barut B, Gbur JS, Zupancic TJ, Schweitzer AC, Cioffi JA, Lacaud G, Ouyang B, et al. Leptin stimulates fetal and adult erythroid and myeloid development. Blood. 1997;89(5):1507–1512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Umemoto Y, Tsuji K, Yang FC, Ebihara Y, Kaneko A, Furukawa S, Nakahata T. Leptin stimulates the proliferation of murine myelocytic and primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 1997;90(9):3438–3443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanley AJ, Retnakaran R, Qi Y, Gerstein HC, Perkins B, Raboud J, Harris SB, Zinman B. Association of hematological parameters with insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction in nondiabetic subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(10):3824–3832. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simmons D. Increased red cell count in diabetes and pre-diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;90(3):e50–e53. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peterson CM, Jones RL, Koenig RJ, Melvin ET, Lehrman ML. Reversible hematologic sequelae of diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 1977;86(4):425–429. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-86-4-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Virtue MA, Furne JK, Nuttall FQ, Levitt MD. Relationship between GHb concentration and erythrocyte survival determined from breath carbon monoxide concentration. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(4):931–935. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.4.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jain SK, McVie R, Duett J, Herbst JJ. Erythrocyte membrane lipid peroxidation and glycosylated hemoglobin in diabetes. Diabetes. 1989;38(12):1539–1543. doi: 10.2337/diab.38.12.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keaney JF, Jr, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Wilson PW, Lipinska I, Corey D, Massaro JM, Sutherland P, Vita JA, Benjamin EJ, et al. Obesity and systemic oxidative stress: clinical correlates of oxidative stress in the Framingham Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(3):434–439. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000058402.34138.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forbes JM, Coughlan MT, Cooper ME. Oxidative stress as a major culprit in kidney disease in diabetes. Diabetes. 2008;57(6):1446–1454. doi: 10.2337/db08-0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moller-Levet CS, Archer SN, Bucca G, Laing EE, Slak A, Kabiljo R, Lo JC, Santhi N, von Schantz M, Smith CP, et al. Effects of insufficient sleep on circadian rhythmicity and expression amplitude of the human blood transcriptome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(12):E1132–E1141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217154110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morrison CD, Pistell PJ, Ingram DK, Johnson WD, Liu Y, Fernandez-Kim SO, White CL, Purpera MN, Uranga RM, Bruce-Keller AJ, et al. High fat diet increases hippocampal oxidative stress and cognitive impairment in aged mice: implications for decreased Nrf2 signaling. J Neurochem. 2010;114(6):1581–1589. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06865.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuzefovych LV, Musiyenko SI, Wilson GL, Rachek LI. Mitochondrial DNA damage and dysfunction, and oxidative stress are associated with endoplasmic reticulum stress, protein degradation and apoptosis in high fat diet-induced insulin resistance mice. PLoS One. 2013;8(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials: Supplementary Text: Supplementary information about relevant pathways and genes. Supplementary References. Legend for supplementary Figure. (DOC 315 kb)

Results of the SHIP-TREND/KORA F4 meta-analysis with p (BH) < 0.01 (z-score based p-value). Table S2. Number of probes indicating significantly BMI-associated expression in the SHIP-TREND/KORA F4 meta-analysis. Table S3. Number of genes exhibiting significantly BMI-associated expression in the SHIP-TREND/KORA F4 meta-analysis. Table S4. Genes exhibiting BMI-associated mRNA abundances and are assigned to the 25 most significantly BMI-associated canonical IPA-pathways detected in this study. Table S5. BMI-associated pathways with p (BH) < 0.05. Tables S6-S30. Genes exhibiting BMI-associated mRNA abundances and are assigned to the canonical IPA-pathways listed in Table 2. Table S31. Annotation of all 48,803 Illumina HumanHT-12 v3 probes and respective detection rates (Illumina’s detection p-value < 0.05) in SHIP-TREND and KORA F4. Table S32. Meta-analysis results for the main model with and without adjustment for HOMA-IR for all 12,778 Illumina probes indicating significant transcript levels in SHIP-TREND and KORA F4. Table S33. Association results for the detected genes priorized using the DEPICT method and described in Locke et al. [5]. Table S34. Results of sensitivity analyses in KORA F4 - additional adjustment for HOMA-IR or type 2 diabetes status. (XLSX 18052 kb)

Supplementary Table KEGG_pathways_WebGestalt: Results of the pathway over-representation analysis using the web-based toolkit WebGestalt ( bioinfo.vanderbilt.edu/webgestalt/ ) and the online database resource KEGG ( genome.jp/kegg/ ). (XLS 46 kb)

Supplementary Table WikiPathways_pathways_WebGestalt: Results of the pathway over-representation analysis using the web-based toolkit WebGestalt ( bioinfo.vanderbilt.edu/webgestalt/ ) and the online database resource WikiPathways ( wikipathways.org ). (XLS 39 kb)

Correlation of Signature Transcripts with BMI-related Traits. (PDF 39 kb)