Abstract

We examined the experiences of women in treatment for substance dependence and their treatment providers about personal networks and recovery. We conducted six focus groups at three women’s intensive substance abuse treatment programs. Four coders used thematic analysis to guide the data coding and an iterative process to identify major themes. Coders identified social network characteristics that enabled and impeded recovery and a reciprocal relationship between internal states, relationship management, and recovery. Although women described adding individuals to their networks, they also described managing existing relationships through distancing from or isolating some members to diminish their negative impact on recovery. Treatment providers identified similar themes but focused more on contextual barriers than the women. The focus of interventions with this population should be on both internal barriers to personal network change such as mistrust and fear, and helping women develop skills for managing enduring network relationships.

Keywords: addiction / substance use, recovery, relationships, social support, women’s health

Substance use is situated within relationships among family members and friends, thus making the social context of addiction an important consideration for researchers and treatment providers (Curtis-Boles & Jenkins-Monroe, 2000; Davis & DiNitto, 1998; Kissin, Svikis, Morgan, & Haug, 2001). Recovery-oriented personal networks and non-using personal network ties contribute to positive treatment outcomes and the maintenance of sobriety during recovery (Gordon & Zrull, 1991; Walton, Blow, Bingham, & Chermack, 2003; Weisner, Delucchi, Matzger, & Schmidt, 2003). Treatment-related professional and peer support, and informal social support outside of treatment are significant factors in treatment retention (Dobkin, De Civita, Paraherakis, & Gill, 2002) and treatment outcome (Comfort, Sockloff, Loverro, & Kaltenbach, 2003; Joe, Broome, Rowan-Szal, & Simpson, 2002; Zywiak, Longabaugh, & Wirtz, 2002). Although pre-treatment personal networks are an important source of support (Longabaugh, Wirtz, Beattie, Noel, & Stout, 1995), abstinence-oriented personal networks following treatment might be more predictive of treatment outcomes (Broome, Simpson, & Joe, 2002).

Personal Networks and Women With Substance Use Disorders

The influential role of personal networks for women with substance use disorders has been previously examined. Researchers have characterized the networks of women in substance abuse treatment programs as small (El-Bassel, Chen, & Cooper, 1998; Manuel, McCrady, Epstein, Cook, & Tonigan, 2007), with a high proportion of substance users (Grella, 2008) unable or unwilling to provide social support during treatment and recovery (Greenfield et al., 2007; Laudet, Morgen, & White, 2006). Women are frequently introduced to substance use through partners, family members, and close friends (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2009). These substance using network members can compromise the recovery process (Warren, Stein, & Grella, 2007; Wenzel, Tucker, Golinelli, Green, & Zhou, 2010) or contribute to continuing emotional distress (Dawson, Grant, Chou, & Stinson, 2007).

In qualitative studies of personal network relationships, researchers have shed light on the interplay between personal networks and the treatment and recovery processes. Strauss and Falkin (2001) focused on women’s relationships with their mothers. They described the complexity of this relationship in which child care and other tangible support provided by mothers to their substance using daughters actually enabled continued drug use. Although the majority of women in that study identified their mothers as primary supporters within their personal networks, lack of trust and control issues were also evident. Women’s post-treatment dilemmas included learning how to reshape relationships that had previously supported substance use or sever ties with individuals who continued to use, and the issue of having burned bridges with previous supporters (Falkin & Strauss, 2003). When women “must find support during their recovery from some of the same people who previously enabled drug use,” success in recovery is harder to achieve (p. 142).

Negative or conflictual relationships can trigger relapse during recovery. Rivaux, Sohn, Armour, and Bell (2008) noted that intimate partner relationship problems and demands were prominent among triggers for relapse. Women then needed to learn new ways of coping to avoid dysfunctional repetitive patterns in relationships. Sun (2007) examined the role of network relationships in the relapse process. She found that interpersonal conflicts and negative emotions, whether related to service systems or intimate partners, often contributed to relapse. She also pointed out the difficulty women had in severing old “using” ties, especially when the user was a partner or a close family member, and furthermore, how shame and lack of trust created difficulties in establishing new non-using ties.

Gaps in Previous Research

Although researchers have documented the important role of social support and personal networks for those in recovery from substance dependence, there remain several gaps in the current understanding of personal networks for women with substance use disorders. First, we have limited knowledge about the positive and negative influences of specific personal network characteristics on women’s recovery over time. Second, we do not fully understand the barriers to making changes in personal network relationships that support recovery, particularly for women with limited socioeconomic resources. Finally, research has lacked substance abuse treatment provider perspectives on women’s personal network relationships, particularly on the personal networks of individuals with substance use disorders.

Research Aims

The aims of this study were twofold: First, to identify the qualities of personal network relationships that either enabled recovery or increased risk of relapse for women with substance dependence; second, to examine the barriers to making personal network changes for women during the recovery process. To meet these aims, we asked the following research questions.

Research Question 1: Which personal network relationships are salient for women in recovery?

Research Question 2: What are the characteristics of those relationships that help or hinder recovery?

Research Question 3: What are the barriers to making changes in personal networks that are necessary for recovery?

Research Question 4: In what ways do client and provider perspectives differ about salient relationships, relationship characteristics, and barriers to network change?

Method

Procedures

The authors employed procedures outlined by Krueger and Casey (2009) for planning focus groups, developing focus group questions, and moderating focus groups. The first three authors conducted six focus groups, three with clients and three with providers. Client and provider focus groups were held at each of the three agencies participating in a larger National Institute of Drug Abuse funded longitudinal study of personal networks and post-treatment functioning among women in treatment for substance dependence (S. Brown, Jun, Min, & Tracy, 2013; Min et al., 2013; Tracy, Kim, et al., 2012; Tracy, Laudet, et al., 2012). We conducted the groups at one residential and two intensive outpatient substance abuse treatment programs for women.

Participants in the larger study were interviewed at 1 week, 1 month, and 6 months post-treatment intake, regardless of whether or not they remained in or completed the treatment. Retention in the study was 81% at 6-month follow-up. Each participant completed a detailed personal network interview about the composition, functioning, and relationships within their networks, using Egonet, a personal network software program (McCarty, 2002; SourceForge, 2011). All three of the provider groups and two client groups were conducted at the agencies themselves; one of the client groups was conducted at the university which sponsored the research. The focus groups required between 1 and 2 hours to complete. Client focus groups lasted longer than provider groups. All group sessions were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim.

Informed by our review of the intervention literature in this field, we formulated these questions: In what ways is it difficult for women in recovery to create personal network changes? How have social networks been a positive influence on your treatment and recovery? How have social networks been a negative influence on your treatment and recovery? What kind of people are important in a social network for women in treatment for substance dependence and in recovery? Based on the criteria by Krueger and Casey (2009), we designed focus group questions to be “clear, short, open ended, and evocative of discussion” (p. 37). Facilitators asked follow-up questions to the participants and were active in keeping the participants focused on the questions. Facilitators asked these same questions at each of the six focus groups. The sponsoring university’s Institutional Review Board approved this study before we recruited participants.

Recruitment

We used random purposeful sampling to recruit participants. For the client groups, we recruited only women who had completed Time 3 interviews in the larger longitudinal study. By this criterion, eligible women were at least 6 months beyond their entry into the larger parent study and into substance abuse treatment. ID numbers for the 188 women who had completed the Time 3 interview were listed separately, based on the agency from which they had received treatment. A research assistant identified the 1st ID number in each list and every 10th ID number thereafter. In the event that researchers could not contact a woman on the list or the woman did not want to participate, we chose the next ID number on the list for inclusion. We successfully contacted 40 women by telephone and of those 40 women 34 agreed to participate in the focus groups (10–14 per group).

Eligible participants were notified about time, agency location, and travel (including bus passes) via the U.S. Postal Service. Two reminder phone calls were scheduled for each willing participant; at 1 week and again at 1 day prior to their scheduled focus group meeting. The final number participating in the client focus groups was 17, with 4, 6, and 7 members in each group. Sixteen women did not attend their focus groups. Participants were given a gift card (US$10) and gas money (US$5) as compensation for participation. Many of the women knew each other and had been in treatment programs together previously. This set an initial climate of comfort, ease, and trust, unusual for a first focus group meeting.

Recruitment flyers were sent to each agency and a date identified that was convenient for each agency to hold the provider focus groups. The provider focus groups met for 1 hour each, and researchers provided lunch. Twenty-one providers participated: 10, 6, and 5 from each agency. We used the same procedures for client and provider focus groups. However, we slightly changed the wording of the questions to reflect the provider’s focus on the client rather than the client’s focus on herself. For example, in questions 2 and 3 rather than asking, “How have social networks been a positive (or negative) influence on your treatment and recovery?” we asked, “How have social networks been a positive (or negative) influence on your clients’ treatment and recovery?”

Participants

In all, 17 women participated in the client focus groups, 4, 6, and 7 per group. All women were between 18 and 60 years of age (one of the inclusion criteria for the larger study). The groups were ethnically diverse: 2 White, 13 African American, and 2 Hispanic women. Participants ranged in age from 27 to 54, with a mean of 40. Only 1 woman was employed at the time of this study. Nine women had completed less than a high school education. In all, 21 treatment providers participated in the provider groups: 10, 6, and 5 providers per group. Providers included 2 men and 19 women, 9 African American, 4 Hispanic, and 8 White individuals. Providers were primarily clinicians and case managers, with one administrative assistant and two program managers. All providers were invited to the focus groups, and all those working in the agency on the day of the focus group participated.

Data Analysis

Researchers analyzed the data using protocol for thematic analysis outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006) and by Boyatzis (1998). Four independent coders examined the transcripts; coders created in vivo codes from transcript data using theoretically driven sensitizing concepts to identify codable pieces of text. Coders met as a group to discuss the in vivo codes, defined higher order axial codes that appeared to categorize the in vivo codes, and compiled these into a codebook. Coders re-coded the transcripts according to the codebook, and identified codes that were unclear in definition, overlapped other codes, or did not adequately capture all aspects of the in vivo codes.

The data analysis team identified data themes, ways in which the codes seemed to be related to one another at higher levels of abstraction than those presented in the axial codes. Throughout data analysis, the coding team engaged in iterative discussions about the appro-priateness and definitions of codes and themes, con-tinually refining and re-defining codes and themes throughout the analytic process. Client and provider transcripts were coded together and separately, first to identify common themes and second to identify themes that were not common across both groups.

There were three specific instances in which we modified axial codes. First, we removed the axial code of “spirituality” after determining that it did not adequately reflect the in vivo codes, which were better reflected by other axial codes. Second, we had initially created an axial code to reflect the influence of partners or spouses on recovery. However, only one in vivo code throughout the data reflected the influence of partner or spouse, and this in vivo code offered no additional information beyond that represented by the effects of family members. We subsumed this in vivo code under the axial code “Qualities and Influences of Family.” Third, although coders created initial axial codes to reflect the positive impact of social networks and network members on recovery, they observed that negative effects were also occurring and that recovery also exerted influence on social networks. Following discussion among members of the coding team, we then added axial codes to capture these phenomena.

Validity of analysis was assured in two ways. First, we used multiple coders throughout the stages of data analysis who engaged in an iterative process of coding and code development. Second, we used member checking (Padgett, 2008). Once the results were organized, we sent a summary of the findings to participating treatment providers. They examined the findings and offered suggestions regarding aspects they felt had been missed in analysis. The only item that treatment providers felt was not reflected in the findings was the importance of the public child welfare agency in creating barriers for women in treatment. This is covered in more depth in the discussion section. Outreach attempts to use member checking with the women participants themselves were unsuccessful. This was because of the many psychosocial problems that confront this population, including frequent changes of residences, episodic homelessness, lack of telephones, lack of transportation, and the women’s lack of access to computer-based technology such as email.

Findings and Discussion

During the data analysis process, coders identified the following themes outlined in Table 1: Qualities and influences of children, families, 12-step groups or sponsors, and treatment or treatment providers on recovery; managing network relationships; barriers to managing network relationships; and interactional processes. In the following sections, we list and describe each of these themes, describe axial codes that comprise them, and illustrate each with representative examples from the participants themselves.

Table 1.

Relationship Qualities, Influences, and Processes That Function as Recovery Enablers or Risks for Relapse.

| Qualities and Influences of Children |

Qualities and Influences of Family |

Qualities and Influences of 12-Step |

Qualities and Influences of Treatment |

Network Change Processes |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recovery enablers |

Children are a mirror |

Honesty | Decrease isolation | Creating linkages | Managing relationships |

| Desire for more contact with children |

Supportive of treatment |

Get recovery information | Providers educate family members |

Reciprocity | |

| Wanting children to be integrated into network |

Reciprocity | Honesty/confrontation | New interpersonal experiences |

Managing closeness and distance |

|

| “Want my kids to see my life” |

Consistence— “Always been there for me” |

Sponsor is like a mother— Provides commitment and direction |

Social support | Isolating or integrating network members |

|

| Emotional support | Exposure to healthy people |

Universalizing addiction |

Adding new network members |

||

| Relapse risks |

Children have problems |

Lack of knowledge about addiction |

Lack of fellowship | Clients still using | Barriers to network change |

| Setting limits | Lack of support for treatment/recovery |

Potential to be re- traumatized |

Staff who are “not well” |

Contextual barriers | |

| Managing self and child’s emotional states |

Family member is easy to manipulate |

Members not really working the program |

Potential to be re- traumatized |

Internal emotional and self- experiences |

|

| Consequences of past substance use to child |

Family members use substances |

Stigma about mental health issues |

Qualities and Influences of Important Relationships: Recovery Enablers and Risks for Relapse

This theme includes the qualities of important relationships that facilitate or impede recovery and the ways in which women are influenced by these relationships toward recovery or relapse. These influences were sometimes positive, in that they increased women’s motivation to remain clean and sober; we labeled these qualities “recovery enablers.” Negative qualities of important relationships influenced women to feel more vulnerable to relapse; we labeled these “risks for relapse.” The women identified salient relationships with their own children or grandchildren, relationships with family members, relationships with 12-step members including sponsors, and relationships with treatment providers or with other women in their treatment programs.

Qualities and influences of children

Women identified qualities of their relationships with their children as important influences on their recovery. Negative qualities and influences of children, or risks for relapse, included their children having problems that were difficult to deal with such as health issues, learning disabilities, or behavioral/emotional problems. This is consistent with previous research (Farkas, 1995) that identified myriad problems for children of substance abusing parents, particularly those born to mothers who abused substances during pregnancy, making parenting more stressful. Women reported difficulty setting limits with their children during recovery as a risk for relapse, particularly when combined with an awareness of the behavioral and mental health consequences of their substance abuse on their children. One woman stated,

I have an 11-year-old son and when I first came home it was about give, give, give, do, do, do, because I wanted to make up for it [substance abuse]. But I realized [that] I spent my whole life people pleasing and trying to fit in. That’s how I got to where I was, and I’m not about to do that with my kids. I’m sorry. I apologize, but I’m not about to kiss your butt. You’re not about to stay up and watch basketball until 12:00 just because I was a drunk.

This is consistent with previous research by Carlson, Smith, Matto, and Eversman (2008) who identified difficulty of mothers in addiction recovery in setting limits with children. This was exacerbated by mother’s guilt about the consequences of her addiction on her child and a belief in the need to over-compensate for the ways in which children were neglected during active substance abusing periods.

Learning to identify internal physical and emotional states and to manage those without the use of substances is a significant challenge during early recovery (Kelley, 1992). The participants presented the dilemma of both needing to learn to do this for themselves, while needing to help their children learn to manage their own internal states and impulses. One provider commented, “They struggle with their own internal signals and they struggle with managing their children’s as well.” This process of mentalization (Fonagy, Gergely, Jurist, & Target, 2002) involves the ability to identify mental states such as needs, feelings, thoughts, and desires, which underlie behaviors. The ability to mentalize is central to the skills required in early recovery, such as identifying and managing feeling states that might otherwise trigger substance use. Mentalization is also required in parenting because it contributes to secure attachment in children; its absence from parenting has been implicated in various types of developmental psycho-pathologies in children (Jurist, Slade, & Berger, 2008).

The women discussed positive qualities and influences of their relationships with their children, or recovery enablers. The desire to have more contact with their children appeared to motivate recovery behaviors. These included mothers whose visitation frequency increased with children in foster care, mothers who regained custody of their children, and one grandmother whose adult child allowed her increased access to her new grandbaby once she was in recovery. This woman stated, “I get my grandbaby now, every week. I asked my son [before getting clean] ‘why don’t you bring me the baby?’ He said, ‘you get high.’ It hurt my feelings, but it was the truth.” Relationship with children as a motivation for recovery has been well documented in previous literature (Carlson et al., 2008), including both the desire to maintain a positive parenting identity and the role of the child welfare system as encouragement to enter treatment and as a support for recovery.

The desire to have a social network in which their children were integrated and to have a network and life that they were not embarrassed to have their children see were recovery enablers for these women. As one woman put it, “My son sees these people in my cell phone, and the list isn’t just drug dealers anymore. I’m able to label them in my phone as fellowship and friends.” Another woman said,

Today I don’t go anywhere she [daughter] can’t go. Before she would ask me if she could go with me and I would always make an excuse, because I was doing things and I didn’t want her to be a part of it. But now I’m like, “come on go with mommy.” I get a really good feeling from that.

There was also a sense that children served as a mirror, reflecting similar behaviors in which the mothers had engaged. One woman stated, “My 9-year-old [is] doing everything I did, from the stealing to the lying to the manipulation, and I’m like, ‘I can’t believe this.’ It’s like looking in a mirror.”

Qualities and influences of family members

Qualities of their relationships with family members other than their children also influenced recovery as enablers or risks for relapse. Risks for relapse included the family’s lack of knowledge about addiction and lack of support for treatment from family members. One participant described her family this way:

They don’t know what I’m going through. I say “I’ve got to go to these meetings 3 times a week and talk to my sponsor.” And my cousin says, “It’s OK to take a drink every once in a while, just don’t go overboard.” But you’ve got to understand. I just can’t do that.

A treatment provider echoed this: “The family system doesn’t have the basic knowledge of addiction and codependency. They don’t have knowledge about how they play a very important part in the client’s sobriety as well as their using.” EnglandKennedy and Horton (2011) identified a similar theme in their study of family systems during recovery. Families frequently misunderstood both addiction and the role of treatment and 12-step in recovery, often believing that the “client had recovered more fully than was true” (p. 1227). These types of misunderstandings often created dissonance in the individual in recovery and within her family relationships, triggering relapse.

Family members allowing women to manipulate them and having family members who also used substances were identified as risks for relapse. One woman stated, “The manipulation with my family. I could do that all day long.” Another woman said, “Certain relationships, my mother and my sister, I have a tendency to, how can I put this, manipulate them.” When manipulation was allowed to flourish in family relationships, it both reinforced dishonesty, which triggered relapse, and allowed women to avoid responsibility, which also triggered relapse.

Recovery enablers included family members who were honest with women, reciprocity within these relationships, family members supporting women’s treatment involvement, emotional support; and the sense that some family members were loyal and committed to their relationship with the woman. One woman described her family this way:

My family is positive, they always love to see me go into treatment; love to see me get sober. They’re not alcoholics and addicted so they think when I go to treatment I’m cured, when I get out I’m still cured. [It’s] as though I don’t have any problems in the world. That’s the negative thing because they don’t know what they’re doing and they don’t understand what I’m going through. And the manipulation, with the family, I could do that all day long. I learned that. And that’s the negative part of it.

For many women, both recovery enablers and risks for relapse existed within the same relationships.

Qualities and influences of treatment and providers

Relationships with treatment providers and with other women in treatment were also recovery enablers or risks for relapse. Risks for relapse included being around other clients who were still actively using substances and being around treatment providers who were “not well.” “Not well” for these women referred to providers who they perceived as negative in their interactions with clients, disrespectful toward them, and who did not appear to employ self-care skills or work toward their own goals.

Participants identified the potential for women to be re-traumatized by betrayal or abuse that might occur between themselves and other clients or even treatment providers as another relapse risk. One treatment provider described her concern:

I had a client tell me the other day that treatment triggered her. Having a negative experience in a network like a treatment center may have a negative impact; so now they shut down and they’re not reaching out for help to anybody because “I trusted you and now you broke that trust so I’m not trusting any social network.”

Participants also described positive qualities and influences of these relationships, such as the ways in which treatment created linkages to other services for women; the way that providers educated family members; the possibility for creating new interpersonal experiences; the presence of emotional, informational, and sobriety support in treatment; and the universalizing of the addiction experience. One treatment provider addressed new interpersonal experiences when she said, “That’s what we hope to do by having a group atmosphere here is for them to start learning to trust each other here and then they can take it outside of the group.”

Qualities and influences of 12-step

Qualities of 12-step groups and sponsors also influenced recovery. The positive influences of 12-step groups and sponsors included decreased isolation for the women involved, access to more information regarding recovery and maintenance, having individuals such as sponsors who will be honest with them and appropriately confrontational when necessary, and having exposure to people who are healthy, with positive attitudes and goals. One woman described her experience of honesty and confrontation with her sponsor:

I can call my sponsor right now and say, “hey my daughter’s grandmother really pissed me off, man let me tell you what she said.” But she [sponsor] be like [says], “stop right there, what did you say to her?” My sponsor knows me in and out. … She can just step back and tell you the real, be hard on you but compassionate.

One woman stressed the importance of positive attitudes and goals in 12-step when she said, “Just being around positive people. The using lifestyle is so negative. Just changing that network, looking at life from a positive direction, [having] a more positive atti-tude, a more positive direction.” Women also described their sponsor as being “like a mother,” in that they maintained an unconditional commitment to them and provided direction.

These data are consistent with previous research that documented the positive aspects of 12-step involvement and 12-step sponsorship for individuals in recovery. These benefits included reductions in substance use (Tonigan & Rice, 2010) and increased social support for abstinence (Laudet et al., 2006). Previous researchers suggested that 12-step involvement decreased substance use through its influence on the social networks of individuals with substance dependence. They maintained that 12-step involvement increased the number of non-using individuals in the addicted person’s network. However, a more recent longitudinal study (Rynes & Tonigan, 2012) found no evidence for this over time.

In spite of the wealth of information regarding the positive impact of 12-step involvement on recovery, very little has been written about the potentially negative impact of 12-step involvement on recovery. According to these data, 12-step groups and sponsors also have the potential to negatively influence recovery. These risks for relapse occurred through 12-step groups in which “fellowship was lacking” and where members were “not really working the program.” In these cases, women were referring to situations in which sponsors or others in 12-step did not “reach out” or “show up” or “follow through” either with their own promises or with the basic premises of the program. Concretely, women described sponsors and other members of 12-step continuing to use substances, being dishonest about their substance use and offering rides or assistance to get to meetings and not showing up.

Participants commented on the potential for women to experience re-traumatization in these groups and relationships through betrayal and possibly abuse from other members. One treatment provider described the potential for re-traumatization this way:

A lot of times the quality of those [12-step] meetings are not up to par, so it’s a lot of easy distractions for our ladies. Because they’ve experienced a lot of things they find it difficult to ward off advances from guys, it’s just a lot of different things that can happen at meetings. They’re already guarded when they go. So when they go and experience these things it’s difficult for them to open up and trust the process.

Participants identified stigma for those with co-occurring mental illnesses and substance dependence as a potential negative influence of 12-step groups. One participant noted, “A lot of women deal with mental health issues and a lot of people from 12-step have no knowledge or understanding of what they’re dealing with.” Previous research (V. B. Brown, Ridgely, Peppe, Levine, & Ryglewicz, 1989) has also documented the experience of stigma in 12-step groups for individuals with dual mental health and substance use disorders.

Managing Network Relationships

Given previous research concerning the importance of non-using and recovery-oriented networks to women’s recovery (Bond, Kaskutas, & Weisner, 2003; Dobkin et al., 2002; Walton et al., 2003), treatment programs have tended to focus on helping women in recovery change the individuals within their networks. However, the participants in this study offered a much more nuanced perspective on the relationship between their personal networks and personal network members and their recovery. Although the women did describe the importance of having new recovery-oriented individuals within their networks, they also described the need to manage ongoing relationships within their networks.

Women frequently reported that the same network relationships that contributed positively to their lives and recovery also negatively influenced recovery in some way. Both adult family members and children supported women’s recovery by providing honest feedback to women, support for treatment, concrete and emotional support, and inspiring a desire in the women for greater integration of their children into their networks. These same relationships negatively affected recovery when family members abused substances or did not support recovery, and when children’s needs exceeded a mother’s capacity to meet those needs. Treatment providers and 12-step group relationships also exerted both positive and negative influences on women’s recovery.

Participants in this study identified some specific ways in which they managed ongoing relationships within their personal networks during recovery. One important method was to isolate some network members network by distancing themselves from certain individuals and by decreasing the amount of contact that individual has with other network members. In this way, women were able to both honor their commitment to an important relationship, while protecting themselves from the possible negative impact of some relationships on their recovery. One woman described this process of isolating a member of her network, while still maintaining the relationship and her commitment to this relationship:

You know like I outgrew all these clothes, I lost weight, and I was giving them to her [a good friend]. I said, “you’ve got to come downstairs and get it,” because I love her but I don’t go in her house for anything because I know that still is a wet place. Even though she says she’s trying to do better, I know that’s still a wet place. I know her house is a trigger for me. So I don’t even go there by myself when I’m dropping something off.

Another woman reinforced this concept saying,

A lot of people I was involved with got a lot of negative stuff to say but I tell them I don’t want to hear about that stuff. I don’t want you to bring it here unless it’s something positive. I’m not the kind of person that kicks you out of my life as a friend. We can be associates. If there’s something positive, we can do it together. I still talk to some on the phone. I just don’t go around them much.

The other side of this coin was to increase closeness with network members who were perceived to be healthy or supportive of the woman’s recovery and to increase contact among and between them. By integrating these individuals into their networks, women were able to build a stronger support group for sobriety by increasing contact among the healthier, more supportive network members. One woman described increasing contact and closeness in her network, saying,

My son needs to see the new people in my life and my friends today. He said something that hit me like a brick. When they asked him, “How will you know when your mother is using?” He said “by the company she keeps.” My understanding of recovery is that it is an active change, and if I’m not connecting the dots—that social part of me, then I’m not gonna grow or change.

For this woman, the “dots” were the healthier, more supportive ongoing members of her personal network.

By increasing integration among these members, women decreased their opportunities to engage in secretive substance use–related behaviors, in essence creating a network of individuals to whom they felt accountable and with whom secrecy was more difficult. As members were more connected with each other, information about the women passed more easily between network members. One woman put it this way:

One of the things that helped with my family is bridging these relationships together. It’s one thing for my family to see me go through treatment and stop using. But my son needs to see the people in my life and my friends as well.

Another woman described a simultaneous and progressive process of distancing from and isolating some network members, while moving closer to and further integrating others:

I could see how the people I use with had started moving out of the way but also one of the things I was able to see was, yeah, they had changed but I started to see a more solid foundation of the people in my life who were part of my recovery. It was totally amazing. I was able to see the progression.

Learning to create personal boundaries and set limits with ongoing network members was an important part of managing relationships. One woman described the process this way: “That’s the way I look at it. You get more and more stronger and you’re able to say no. My sister says, ‘Can you watch my daughters?’ And I say ‘not today’.” Another woman echoed this: “It’s not so much about cutting people out of our lives, but setting boundaries more, and having a plan of how you’re going to deal with it or manage it.”

Understanding and attending to reciprocity was central to the work of managing ongoing relationships. Reciprocity included two elements. First, women came to recognize the importance of giving back to others in their networks and recognized the improvement in their self-esteem that resulted. One woman said, “I missed a lot of my daughter’s life. Now today just being available and there, oh wow, it’s amazing. It’s the time and the love that you can give back.” Johansen, Brendryen, Darnell, and Wennesland (2013) framed this experience, being able to give back to others and the resultant changes in how one feels about oneself, as the “positive identity model of change.” They found that, for individuals in recovery, being able to help their own sponsors in some way had a positive impact on self-identity, and that those who helped others through Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) were significantly less likely to relapse than those who did not.

The second element of reciprocity, appraisals, is the process by which individuals perceive an action as supportive. Women acknowledged that their appraisals of support had shifted. They felt more appreciative of the support that had been given to them throughout their substance using years. About her sister, one woman remarked, “She supports me. I never thought she would ever support me because when I was using I just didn’t see it. I didn’t see that she was trying to support me.” According to Cutrona, Cohen, and Igram (1990), support recipients experience behavior intended to be supportive differently, depending on the context of this behavior and the inner state (feelings, thoughts, beliefs) of the receiver. Support that closely matches the type desired by the recipient is appraised more positively than support that does not match. Active substance use and recovery are contexts that directly affect support appraisals and inner states that affect support appraisals.

Barriers to Managing Network Relationships

Although participants acknowledged the importance of both adding new individuals to their networks and managing relationships with ongoing network members, they also cited two types of barriers to making these changes. We categorized these barriers as being either contextual or intrapersonal. Contextual barriers to network change included characteristics or circumstances in their environments that affected their ability to make personal network changes and retain recovery. These contextual barriers included stigma of being an addict, having a mental health disorder, absence of community resources, lack of personal resources such as self-esteem or cognitive abilities, and limited treatment agency networks.

One treatment provider reported, “A lot of women deal with multiple diseases, especially mental health. A regular person from a 12-step program has no knowledge of what this woman is dealing with. That right there stagnates the process of changing social networks.” Another treatment provider commented, “They don’t have an idea of networking. They don’t understand the concept. It’s constructed beyond their means. Some of them are not literate. They’re not stupid, but I have to break down words for them. That’s a stumbling block.”

Treatment providers commented on the limited networks of the treatment agencies:

It’s the lack of partnership among agencies. The women suffer from that. It gives them another set of anxieties because where do they go when they’re done in this program? Especially when DCFS [Department of Child and Family Services] is involved, and one of the objectives is safe stable housing.

These contextual barriers can be described as an absence of social capital. Focusing on the role of social capital in recovery, Granfield and Cloud (2001) noted that “opportunities to transform oneself are unevenly distributed” (p. 1552). They found that an individual’s capacity to recover from addiction was affected by the stability of their housing, employment, and social relationships among others who had concrete and emotional resources from which the individual with addiction might benefit. For the participants in this study, social and economic marginalization contributed to a lack of social capital that negatively influenced their capacity for change.

Intrapersonal barriers to personal network change are self-evaluations, feelings, thoughts, or self-identities that women or providers described as interfering with either recovery or their ability to create changes in their social networks. These included fear of change, difficulty trusting other people, “this is all I know,” loss, dealing with consequences of their past and the related guilt and shame, lack of motivation, and having a bad or negative attitude or thought process. One treatment provider said,

It’s difficult for these women to ask for help in certain areas because they have a fear of how someone might hurt them if they give them any information. They think, “I’d rather deal with this myself than open up to someone new and not know what’s going to happen afterwards.”

One woman described her sense of loss:

As far as the social network thing is, the people that you’ve seen all your life, from birth up but you have to cut them out, you know what I’m saying? I can’t be around you. It’s hard for me to change people, the people I’ve known all my life.

Another woman discussed her difficulty in coming to terms with her past behavior:

When I look at a social network it involves more than my core, it involves getting out into society and going to school. I’ve got to go to the bursar’s office and be honest. I’ve got to deal with the wreckage from my past. That is a barrier.

Others have cited similar intrapersonal barriers, such as guilt and shame associated with substance use (Carlson et al., 2008), loss and fear associated with recovery, and the impact of trauma on the capacity to trust (Sun, 2007).

Interactional Processes

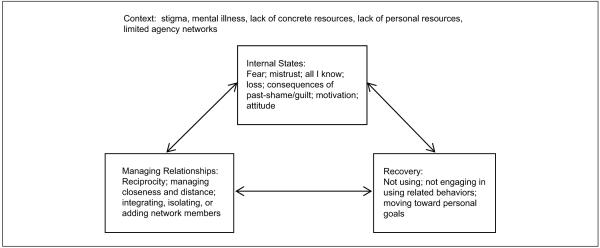

Participants described network change as a dynamic process involving the domains of internal emotional states, personal network management, and recovery, reciprocally influencing one another. Change was not described as a linear process with one domain leading to change in another, but as simultaneous changes emerging among all three domains. As illustrated in Figure 1, reciprocal change among domains involves an interactional process, characterized by reciprocal relationships between the internal emotional world of these women, personal network management, and recovery. Each of these domains appeared to influence, and to be influenced by, the other two.

Figure 1.

Interactional processes among intrapersonal, interpersonal, and situational domains for women with substance use disorders within a low resource context.

Participants’ descriptions of their change process support the theoretical concept of equifinality, which suggests that the same outcome can be arrived at through different pathways and multiple influences or multiply determined (Bateson, 1979). Systems theorists characterize the systems of individuals and their environments as open, and characterize change as a process that is either continuous or discontinuous (Smith-Acuña, 2011). Continuous change is linear and incremental, whereas discontinuous change is transformative and occurs during developmental transitions (Thelen, 2005). These women provided a picture of personal network management, addiction recovery, and changes in their internal sense of self and relationship that was discontinuous and multiply determined.

One woman described the reciprocal relationship between recovery and her social networks when she said,

During the process of me getting sober this time I weeded them out [negative people]. I have a garden now, and my garden consists of people who truly care for me. But most of all I care for myself today.

Another woman described the reciprocal relationship between her internal world of mistrust and her social network:

That was hard for me in the beginning. Just gaining the trust on my part, you know, I don’t want to tell you about me. But as I continue to be around sober people and be around them in rooms, I’ve gotten better with it. I was willing to allow you to get to know me. Instead of being that flower on the wall, it gets easier as time goes on. So I’ve got a lot of people in my life today. I’ve got a big support group.

For this woman, changes in her social network influenced changes within her internal world. One treatment provider expanded on the relationship between women’s internal realities and their social networks:

They’ve built up their self-esteem through treatment, through their relationships with other women in the program. Many of them continued to maintain the relationships outside and they feel more comfortable getting into new AA meetings or classes or work. And they can just take that positive self-esteem and say, “OK, I was able to build a relationship with Christine, now I can build one with Jill and Sue and all those other new people.” They feel good and it snowballs and keeps getting better and better.

A useful theoretical framework in which to consider these data is the previous work of Sarason, Pierce, and Sarason (1990) who conceptualized social support as an interactional process among the situational, intrapersonal, and interpersonal domains. According to their theory, the situational domain involves a simple or complex focal event. The intrapersonal domain consists of the individual’s “stable patterns of perceiving self, important others and the nature of important relationships” (p. 500). This concept was developed from the work of John Bowlby (1980). His work on attachment theory highlighted the importance of internal working models, developed from experiences with important caregivers during childhood, that influence our appraisals of ourselves and our relationships in adulthood. The interpersonal domain refers to the important qualities of the individual’s relationships and social networks, such as degree of conflict, sensitivity of network members to the individual’s feelings and needs, and the structure of personal network connections.

Drawing from this interactional frame, Figure 1 illustrates our own conceptualization of the interactional process of women’s recovery and management of personal network relationships. We consider recovery to be the situational domain or focal event. Women’s intrapsychic experiences of self and relationships as described above comprise the intrapersonal domain. The tasks of managing interpersonal relationships in recovery comprise the interpersonal domain in this model. Vaux (1990) stressed the importance of context in shaping interactions among the situation, intrapersonal, and interpersonal domains, through the presence or absence of resources at individual and community levels. Informed by Vaux’s model, we have included the environmental context in which these women attempt to regulate the self, relationships, and recovery. In these data, we see evidence for the ways in which environment might shape self-perception, network management, and recovery in the contextual barriers to network change described above.

Differences in Client and Provider Perspectives

Both agency treatment providers and the women themselves endorsed some aspect of each of the themes identified in this study. However, some of the axial codes within each theme were endorsed or developed exclusively by agency treatment providers and not the women, or by the women themselves and not by agency treatment providers. Within the theme of qualities and influences of children on recovery, only the women identified positive qualities of their children and the ways in which their children positively influenced them in recovery. Although agency treatment providers did not identify the women’s children as having positive influences on their recovery, during member checking they did comment on the important role of child protective services in motivating women to seek treatment for addiction.

Within the theme of contextual barriers to network changes, only treatment providers discussed stigma, lack of personal resources, and lack of concrete resources as barriers to network change and recovery. The women themselves did not identify any of these as barriers to change. It was also primarily agency treatment providers rather than the women who commented on the limitations of agency networks. Although substance abuse treatment provider perspectives have not been solicited in previous research, Mericle, Alvidrez, and Havassy (2007) examined mental health provider perspectives of service use among clients with co-occurring substance use and mental disorders. Their findings were consistent with ours, in that mental health providers also identified barriers to service delivery and recovery in their clients’ surrounding environment and context.

Treatment providers focused more on contextual barriers to personal network changes than did the women themselves, whereas the women focused more on internal emotional barriers to change. The women in this study were all poor, from diverse races and ethnicities and minimally educated. Their lack of focus on contextual barriers might have reflected the fact that those obstacles are a way of life for these women, the environment they have experienced since birth, and might not be perceived as specific barriers to network change or recovery. The women’s focus on internal emotional barriers supports the previous research of Sun (2007) who identified both shame and lack of trust as barriers to recovery and personal network change for women in recovery.

Whereas women focused on feelings of shame, providers identified stigma as a barrier. These might be related constructs, with women experiencing externally generated stigma as internal shame. van Olphen, Eliason, Freudenberg, and Barnes (2009) identified stigma as a barrier to recovery for women, creating limited options in housing and employment. Our findings of mixed emotions and ambivalence related to recovery and personal network changes were consistent with the work of Soyez and Broekaert (2003), who identified more nuanced experiences of women in recovery, compared with their network members.

Conclusion and Implications

The aims of this study were to identify the qualities of the salient relationships in women’s personal networks that served as either recovery enablers or risks for relapse, and to identify barriers to making changes in personal network relationships to facilitate recovery. These data reflected the ambivalent nature of relationships and network change for these women. Changes in personal networks involved fear and loss that were sometimes unaddressed by treatment providers. In addition, even substance abusing friends and family and those who enabled substance use in the past were described by participants as providing important support and maintaining some positive involvement with women.

Whereas traditional 12-step-oriented treatment models emphasize changing people and places, these data indicated that such changes might be very difficult for socioeconomically disadvantaged women to achieve. Zelvin (1999), using a relational approach to women and addiction, conceptualized women’s relationship problems as “maladaptive attempts to connect rather than the failure to separate” (p. 9) and suggested that women’s relational focus should be viewed as a strength to promote more positive relationships in recovery. Substance abuse treatment providers hear many client narratives describing negative relationships with partners, families, and friends. These narratives lead them to conclude that these network relationships are more of a liability than a potential resource in recovery. Providers might then miss opportunities to educate and coach women in ways to change and adapt network relationships toward being more supportive of recovery.

Strengths and Limitations

The use of focus groups rather than individual interviews limited participants to those who were comfortable disclosing in a group setting with other clients. Also, the use of focus groups without follow-up interviews might have limited the depth of the data. However, we conducted separate focus groups with both treatment providers and clients across three different treatment programs. This allowed us to analyze the experiences of each of these groups. Previous research of this nature has primarily examined the perspective of either treatment providers or clients, but not both. We also generated richer qualitative data than are usually generated by focus group methods. The fact that the clients knew one another from previous treatment experiences might have set the conditions for such rich description. In addition, the treatment providers themselves had been working together for at least 3 years prior to the focus groups and had some level of comfort with one another.

During the data analysis phase, we used multiple coders and an iterative coding process. We utilized member checking with the providers to verify our findings by sending a summary of the findings to three key informants and requesting their feedback and incorporated that into the findings. Although not in the original study protocol, we found support for our findings through triangulation. Findings from the larger quantitative study suggested similar network processes to those found in this study, particularly the importance of managing network relationships (Tracy, Min, Park, Jun, & Brown, 2013).

Practice Considerations

Changing the individuals within a personal network might not be a viable option for women in substance abuse treatment. This is especially true in relation to children and family members within women’s networks. Women reported that family and children were positive as well as negative influences on their recovery. In addition, for women with little social capital (Falkin & Strauss, 2003), their ability to make significant geographic or even neighborhood change is minimal, locking them into continued ongoing contact with family friends and acquaintances throughout their lives. Given that many of these relationships are here to stay, it might be more beneficial for women to learn skills for managing these relationships, rather than trying to remove individuals from their networks or attempting a complete makeover of their networks. These data support the importance of helping women isolate some members within their network by limiting and controlling the amount and type of contact, while increasing connections between and among other healthier network members. This is a more nuanced approach to typical substance abuse treatment wisdom, suggesting the importance of changing people, places, and things (Sun, 2007).

These data suggest that relationships with children and other family members might contribute more positively to women’s recovery than providers are aware. Women also appeared to be more aware of the negative effects of recovery on their personal networks than were their treatment providers. Practitioners should consider the ambivalence and loss associated with personal network change resulting from commitment to recovery, and assist women in managing emotions related to these losses. In addition, helping women in treatment to establish positive treatment relationships with peers and providers, and assisting them in generalizing these relationships to their personal (non-treatment) networks might yield positive changes across the domains of emotions, recovery, and personal networks.

Given the findings of the interactional relationships between intrapersonal states, recovery maintenance, and personal network management, interventions that target any of these domains can precipitate change in the other two. Interventions that target multiple domains can also be more effective than those that target only one, although change appears to occur almost simultaneously across the three domains. Future research should examine what types of social network interventions might be effective in enhancing recovery success for women with substance dependence.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by Research Training Development Grant from the Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences, Case Western Reserve University.

Biographies

Suzanne Brown, PhD, LICSW, is an assistant professor at the Wayne State University School of Social Work in Detroit, Michigan, United States.

Elizabeth M. Tracy, PhD, is the Grace Longwell Coyle endowed professor at the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, United States.

MinKyoung Jun, PhD, MSSA, is a research fellow in the Division of Policy Research at the Gyeonggido Family and Women’s Research Institute in Suwon, South Korea.

Hyunyong Park, MSSW, is a research assistant at the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, United States.

Meeyoung O. Min, PhD, is a research professor at the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, United States.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Bateson G. Mind and nature: A necessary unity. Ballantine Books; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bond J, Kaskutas LA, Weisner C. The persistent influence of social networks and alcoholics anonymous on abstinence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:579–588. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss, vol. 3: Loss, sadness and depression. Basic Books; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. SAGE; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Broome KM, Simpson DD, Joe GW. The role of social support following short-term inpatient treatment. The American Journal on Addictions. 2002;11:57–65. doi: 10.1080/10550490252801648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, Jun MK, Min MO, Tracy EM. Impact of dual disorders, trauma, and social support on quality of life among women in treatment for substance dependence. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2013;9:61–71. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2012.750147. doi:10.1080/15504263.2012.750147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown VB, Ridgely MS, Peppe B, Levine IS, Ryglewicz H. The dual crisis: Mental illness and substance abuse: Present and future directions. The American Psychologist. 1989;44:565–569. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.3.565. doi:10.1037/0003066X.44.3.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson B, Smith C, Matto H, Eversman M. Reunification with children in the context of maternal recovery from drug abuse. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services. 2008;89:253–263. doi:10.1606/1044-3894.3741. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment . Substance abuse treatment: Addressing the specific needs of women. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2009. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 51 (No. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 09-4426) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comfort M, Sockloff A, Loverro J, Kaltenbach K. Multiple predictors of substance-abusing women’s treatment and life outcomes. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:199–224. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00227-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis-Boles H, Jenkins-Monroe V. Substance abuse in African American women. Journal of Black Psychology. 2000;26:450–469. doi:10.1177/009579840002600-4007. [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Cohen BB, Igram S. Contextual determinants of the perceived supportiveness of helping behaviors. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1990;7:553–562. doi:10.1177/0265407590074011. [Google Scholar]

- Davis DR, DiNitto DM. Gender and drugs: Fact, fiction, and unanswered questions. In: McNeece CA, DiNitto DM, editors. Chemical dependence: A system approach. Allyn & Bacon; Boston: 1998. pp. 406–442. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Chou SP, Stinson FS. The impact of partner alcohol problems on women’s physical and mental health. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:66–75. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobkin PL, De Civita M, Paraherakis A, Gill K. The role of functional social support in treatment retention and outcomes among outpatient adult substance abusers. Addiction. 2002;97:347–356. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Chen D, Cooper D. Social support and social network profiles among women on methadone. Social Service Review. 1998;72:379–491. doi:10.1086/515764. [Google Scholar]

- EnglandKennedy ES, Horton S. “Everything that I thought that they would be, they weren’t”: Family systems as support and impediment to recovery. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;73:1222–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.07.006. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkin GP, Strauss SM. Social supporters and drug use enablers: A dilemma for women in recovery. Ad-dictive Behaviors. 2003;28:141–155. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00219-2. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603-(01)00219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas KJ. Training healthcare and human service personnel in perinatal substance abuse. In: Watson RR, editor. Substance abuse during pregnancy and childhood. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 1995. pp. 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P, Gergely G, Jurist EL, Target M. Affect regulation, mentalization, and the development of the self. Other Press; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon AJ, Zrull M. Social networks and recovery: One year after inpatient treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1991;8:143–152. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(91)90005-u. doi:10.1016/0740-5472(91)90005-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granfield R, Cloud W. Social context and “natural recovery”: The role of social capital in the resolution of drug-associated problems. Substance Use & Misuse. 2001;36:1543–1570. doi: 10.1081/ja-100106963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM, Green CA, Kropp F, McHugh RK, Miele GM. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: A review of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;86:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.012. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE. From generic to gender-responsive treatment: Changes in social policies, treatment services, and outcomes of women in substance abuse treatment. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;40:327–343. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe GW, Broome KM, Rowan-Szal GA, Simpson DD. Measuring patient attributes and engagement in treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22:183–196. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen A, Brendryen H, Darnell F, Wennesland D. Practical support aids addiction recovery: The positive identity model of change. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-201. Article 201. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-13-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurist EL, Slade A, Bergner S, editors. Mind to mind: Infant research, neuroscience and psychoanalysis. Other Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley SJ. Parenting stress and child maltreatment in drug-exposed children. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1992;16:317–328. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90042-p. doi:10.1016/0145-2134(92)90042-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissin WB, Svikis DS, Morgan GD, Haug NA. Characterizing pregnant drug-dependent women in treatment and their children. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2001;21:27–34. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. 4th SAGE; Los Angeles: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Laudet AB, Morgen K, White WL. The role of social supports, spirituality, religiousness, life meaning and affiliation with 12-step fellowships in quality of life satisfaction among individuals in recovery from alcohol and drug problems. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2006;24(1–2):33–73. doi: 10.1300/J020v24n01_04. doi:10.1300/J020v24n01_04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Wirtz PW, Beattie MC, Noel N, Stout R. Matching treatment focus to patient social investment and support: 18-month follow-up results. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:296–307. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.2.296. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.63.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuel JK, McCrady BS, Epstein EE, Cook S, Tonigan JS. The pretreatment social networks of women with alcohol dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:871–878. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty C. Measuring structure in personal networks. Journal of Social Structure. 2002;3(1) Retrieved from http://www.cmu.edu/joss/content/articles/volume3/McCarty.html. [Google Scholar]

- Mericle AA, Alvidrez J, Havassy BE. Mental health provider perspectives on co-occurring substance use among severely mentally ill clients. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2007;39:173–181. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2007.10399876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min MO, Tracy EM, Kim H, Park H, Jun M, Brown S, Laudet A. Changes in personal networks of women in residential and outpatient substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2013;45:325–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.04.006. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett D. Qualitative methods in social work research. 2nd SAGE; Los Angeles: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rivaux SL, Sohn S, Armour MP, Bell H. Women’s early recovery: Managing the dilemma of substance abuse and intimate partner relationships. Journal of Drug Issues. 2008;38:957–979. doi:10.1177/0022042608038-00402. [Google Scholar]

- Rynes KN, Tonigan JS. Do social networks explain 12-step sponsorship effects? A prospective lagged mediation analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26:432–439. doi: 10.1037/a0025377. doi:10.1037/a0025377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarason IG, Pierce GR, Sarason BR. Social support and interactional processes: A triadic hypothesis. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1990;7:495–506. doi:10.1177/0265407590074006. [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Acuña S. Systems theory in action: Applications to individual, couples, and family therapy. John Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- SourceForge EgoNet. 2011 [Open access software package]. Retrieved from http://sourceforge.net/projects/egonet/ [Google Scholar]

- Soyez V, Broekaert E. How do substance abusers and their significant others experience the re-entry phase of therapeutic community treatment: A qualitative study. International Journal of Social Welfare. 2003;12:211–220. doi:10.1111/1468-2397.00454. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss SM, Falkin GP. Social support systems of women offenders who use drugs: A focus on the mother-daughter relationship. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2001;27:65–89. doi: 10.1081/ada-100103119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun AP. Relapse among substance-abusing women: Components and processes. Substance Use & Misuse. 2007;42:1–21. doi: 10.1080/10826080601094082. doi:10.1080/10826080601094082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thelen E. Dynamic systems theory and the complexity of change. Psychoanalytic Dialogues. 2005;15:255–283. doi:10.1080/10481881509348831. [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan JS, Rice SL. Is it beneficial to have an alcoholics anonymous sponsor? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:397–403. doi: 10.1037/a0019013. doi:10.1037/a0019013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy EM, Kim H, Brown S, Min MO, Jun M, McCarty C. Substance abuse treatment stage and personal social networks among women in substance abuse treatment. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research. 2012;3(2):65–79. doi: 10.5243/jsswr.2012.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy EM, Laudet AB, Min MO, Kim H, Brown S, Jun MK, Singer L. Prospective patterns and correlates of quality of life among women in substance abuse treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;124:242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.01.010. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy EM, Min MO, Park H, Jun MK, Brown S. Personal networks and substance use at 12 month post treatment among dually diagnosed women. Paper presented at the Society for Social Work Research Conference; San Diego, CA. Jan, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- van Olphen J, Eliason M, Freudenberg N, Barnes M. Nowhere to go: How stigma limits the options of female drug users after release from jail. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2009;4(1) doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-4-10. Article 10. doi:10.1186/1747-597X-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaux A. An ecological approach to understanding and facilitating social support. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1990;7:507–518. doi:10.1177/02654075900740-07. [Google Scholar]

- Walton MA, Blow FC, Bingham CR, Chermack ST. Individual and social/environmental predictors of alcohol and drug use 2 years following substance abuse treatment. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:627–642. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00284-2. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00284-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren JI, Stein JA, Grella CE. Role of social support and self-efficacy in treatment outcomes among clients with co-occurring disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;89:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.01.009. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisner C, Delucchi K, Matzger H, Schmidt L. The role of community services and informal support on five-year drinking trajectories of alcohol dependent and problem drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:862–873. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel SL, Tucker JS, Golinelli D, Green HD, Jr., Zhou A. Personal network correlates of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use among homeless youth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;112:140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.004. doi:10.1016/j. drugalcdep.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelvin E. Applying relational theory to the treatment of women’s addictions. Affilia. 1999;14:9–23. doi:10.1177/088610999901400102. [Google Scholar]

- Zywiak WH, Longabaugh R, Wirtz PW. Decomposing the relationships between pretreatment social network characteristics and alcohol treatment outcome. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:114–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]