More than five million Americans require admission to intensive care units (ICU) annually due to life-threatening illnesses, (Angus et al., 2000; Joint. Commission. Resources, 2004; SCCM, 2005) and this number is expected to rise in the coming years with the increasing age of the US population (Needham et al., 2005). This expected increase in the number of ICU admissions coupled with recent advances in critical care medicine has led to a significant increase in the number of patients surviving their critical illness (Angus, Carlet, & Brussels Roundtable, 2003; Spragg et al., 2010). Having a critical illness along with life-sustaining treatments that are common in the ICU such as central venous and arterial catheters, endotracheal tubes, and mechanical ventilation, expose patients to stressors intrinsic to the ICU environment. Consequently, ICU survivors suffer from unique cognitive, physical and psychological morbidity that negatively impact their overall quality of life (Desai, Law, & Needham, 2011). Evidence shows that ICU survivors suffer from symptoms that have detrimental effects on activities of daily living after discharge. For example, 50% of ICU survivors have neuromyopathy; (Stevens et al., 2007) 28% have clinically significant depression; (Davydow, Gifford, Desai, Bienvenu, & Needham, 2009); 24% have anxiety (Davydow, Gifford, Desai, Needham, & Bienvenu, 2008); 22% have post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD); (Davydow et al., 2008); and 79% have cognitive impairment (Girard et al., 2010). During a recent multi-disciplinary stakeholders’ conference of the Society of Critical Care Medicine, the attendees recognized that these symptoms frequently occur together and thus have grouped them under the unifying term of “Postintensive Care Syndrome (PICS).” Giving this group of symptoms a name was an attempt to raise awareness for needed education regarding the syndrome (Needham et al., 2012). ICU survivors do not necessarily experience all of the symptoms included in the syndrome. Singly or in unique combinations, PICS symptoms can affect multiple aspects of an ICU survivor’s life. For example, weakness due to neuromyopathy and disuse can cause physical challenges to the extent that it is difficult for survivors to engage in functional or social activities that were previously effortless. Physical weakness coupled with cognitive impairment can result in delays in returning to work or in managing finances or medications. Survivors that experience depression, PTSD, or anxiety may have problems with insomnia or nightmares. Regardless of the combination of symptoms, the outcome is a diminished quality of life that might persist for one to five years or longer (SCCM, 2012).

A number of very different approaches to follow-up care have been implemented (Egerod et al., 2013). However at present, there are no existing established clinical models to manage long-term complications associated with critical illness. Innovative and novel inter-disciplinary care models that can be rapidly translated into clinical practice are urgently needed.

The institute of Medicine (IOM) projects an average time-frame of 17 years for only 14% of new scientific discoveries to become part of routine clinical practice (Balas EA, 2000). At this pace, the health care community will be faced with an epidemic of ICU survivors who return home with severe morbidity and little treatment or support for their ongoing symptoms. If support is not provided, ICU survivors resort to inappropriate and unnecessary use of emergency departments and hospital admissions that could further strain the health care system.

We used the geriatrics medicine program, “Healthy Aging Brain Center (HABC)” (Boustani et al., 2011) at Indiana University, as a model and implementation science (Rubenstein & Pugh, 2006) theory as the method to develop and implement a collaborative Critical Care Recovery Center. The HABC care model was loosely based on the results of two randomized controlled trials demonstrating the effectiveness of a collaborative care model delivering biopsychosocial interventions for dementia patients and their caregivers (Callahan et al., 2006; Vickrey et al., 2006). The HABC was able to demonstrate a positive impact on the quality of dementia care locally within the first year of its inception (Boustani et al., 2011). We felt that this model could prove to be beneficial in improving the quality of care and recovery of ICU survivors by providing care that focuses on specific needs of the survivors and by overcoming the fragmented nature of our present health care system. These models may provide the ability to integrate and connect the various recovery resources available to enhance the recovery potential of the vulnerable ICU survivor with PICS. A comprehensive search of literature revealed that no such collaborative care models exist in the United States that provide care specific to the physical, cognitive, and psychological needs of patients surviving an ICU stay.

In late 2010, Drs. Khan and Boustani conducted a natural history study of 1,149 patients who were admitted to the medical or surgical ICU of our county safety-net hospital and who survived their life threatening illness for at least 30 days. Results indicated that 37% of the ICU survivors suffered from acute lung injury (ALI) or delirium during their ICU stay and that 58% of them were discharged home. Among the 420 ICU survivors of ALI or delirium, 4% to 13% died within the subsequent 11 months and 36% to 48% were hospitalized for at least a second time during the same follow-up period.

In response to the high mortality rate, high functional disability, and high acute care utilization of these vulnerable ICU survivors, hospital administrators and stakeholders supported the creation of the Critical Care Recovery Center. An interdisciplinary team of experts in cognitive, physical, and psychological rehabilitation who used the collaborative care models for dementia, depression, and other geriatric syndromes developed a set of protocols and tools to meet the complex recovery needs of ICU survivors in the CCRC.

Identifying the need for the development and implementation of new care coordination programs per IOM (Committee on the Future Health Care Workforce for Older Americans, 2008), the Pulmonary/Critical Care Division and the Geriatrics Division at the Indiana University School of Medicine in 2011 developed the Critical Care Recovery Center (CCRC) to enhance the delivery of comprehensive patient centered, interdisciplinary care. The underlying purpose of the CCRC is to maximize the cognitive, physical, and psychological recovery of patients who survived an acute episode of critical illness by utilizing the expertise of an interdisciplinary team of a nurse, social worker, pulmonary /critical care physician, neuropsychologist, and psychometrician. In this article, we share our experience of implementing the collaborative critical care model and its patient characteristics.

Methods

Setting and Participants

We recruited patients for the CCRC from the ICU of Wishard Memorial Hospital (WMH), a 450-bed, university-affiliated, urban public hospital that serves a population of approximately 750,000 in Greater Indianapolis, and is staffed by Indiana University School of Medicine faculty and house staff. It has a 22 bed ICU with an average of 335 ICU admissions per month. Patients admitted to the ICU are cared for by medical or surgical critical care teams with specialty services such as cardiology, nephrology, and geriatrics available for consultation. The average age of patients admitted to the ICU at WMH is 53.7 years, 45% are African Americans, 47% are female, and 16% have Medicaid insurance. The ICUs are staffed with critical care registered nurses at a nurse-to-patient ratio of 1:2 and 1:1 depending on patient acuity. Among patients who were admitted to the ICU in 2009–2010, 14% died at discharge, 28% were discharged to a skilled nursing facility, 56% went home, and 17% died within 30 days of discharge.

Complex Adaptive System and the Reflective Adaptive Process

A complex adaptive system is a net-work of semiautonomous, competing and collaborating individuals who interact and co-evolve with their surrounding environment in nonlinear ways (Holden, 2005; Lansing, 2003; Matthews & Thomas, 2007; Plesk, 1997). Constant modification of relationships among its members results in emergent self-organized behaviors (Holden, 2005; Lansing, 2003; Plesk, 1997). Contrary to the usual acceptance of health care systems as machine-like systems with predictable behaviors that can be changed based on past performance (Matthews & Thomas, 2007), we believe that they should be thought of as complex systems with local non-linear relationships that are critical to producing varying behavior dynamics (Anderson, Crabtree, Steele, & McDaniel, 2005; Boustani et al., 2010; Matthews & Thomas, 2007; McDaniel, Jordan, & Fleeman, 2003; Plesk, 1997). Although the system is more complex with variable dynamics, we believed that when combined, this professional mix would enhance positive patient outcomes.

A constant challenge faced by health care delivery organizations is to adapt to a changing environment using the skills and behaviors of individual employees, the relationships and interactions between the employees, and communication among organizations (Anderson et al., 2005; Holden, 2005; Lansing, 2003; Plesk, 1997).

To achieve the desired results of implementing an intervention in a complex adaptive system and to facilitate development of local strategies, an alternative approach, the Reflective Adaptive Process (RAP), was adopted (Cohen et al., 2004; Crabtree, Miller, & Stange, 2001; Group, 2001; Stroebel et al., 2005). Reflective Adaptive Process uses principles of complexity science (Stroebel et al., 2005) to select, develop, and implement changes in health delivery systems that facilitate development of new strategies at the local level. A RAP is governed by the five guiding principles as shown in the side bar.

Side Bar.

| Post-Intensive Care Syndrome Symptoms (prevalence in our population) (Desai et al., 2011, Stevens et al., 2007, Davydow et al., 2009, Davydow et al., 2008, Girard et al., 2010) |

| Critical Illness Neuromyopathy (50%) - Combined neural damage and muscle degeneration in patients requiring prolonged critical care. |

| Depression (28%) – sadness, loss of interest and energy, irritability, sleep appetite extremes, difficulty concentrating, trouble working |

| General Anxiety (24%) – uncontrolled worry or anxiousness without an identified source. |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (22%) Re-experiencing a traumatic event, hyper-arousal and sleep disturbance, avoidance of related stimuli |

| Cognitive Impairment (79%) – Decreased memory, executive, language, attention, and visuospatial function |

| Risk Factors for PICS (Desai et al., 2011, Stevens et al., 2007, Davydow et al., 2009, Davydow et al., 2008, Girard et al., 2010) |

| Intensive Care for ≥ 48 hours |

| One or more instances of delirium |

| Advanced age |

| Anticholinergic or benzodiazepine medications (sedation) |

| Mechanical ventilation |

Similar principles were employed to implement the Critical Care Recovery Center as described in the following results section.

Results

Implementation of our local critical care collaborative model – the CCRC

Brain-storming and deliberations over the structure and functioning of CCRC started well over a year in advance of the center becoming operational in 2011. Quarterly meetings were organized from 2010–2011 to discuss strategy involving all the necessary stakeholders (leadership from pulmonary/critical care and geriatrics divisions, IUCAR, WMH, critical care nursing, care coordination, physical rehabilitation, and neuropsychology). During these meetings, utilizing the reflective adaptive process, the vision and mission of improving the physical, cognitive and psychological morbidity among the ICU survivors was recognized. These meetings also provided the time and space for the stakeholders to develop a relationship and to reflect, that ultimately led to structuring the CCRC as the local collaborative critical care model for ICU survivors. These interactions proved to be the source for identifying the minimal care specifications for CCRC (Table 1). Potential members were identified for the smaller operational teams that would meet weekly to problem solve and improve function for the process after launch of the CCRC in July 2011. These weekly meetings served as a venue to monitor the progress of CCRC and to make timely modifications based on incoming data.

Table 1.

Standardized Minimum Care Components of the Critical Care Recovery Center

|

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

During the meetings described above, the following inclusion criteria, which are also risk factors for PICS, were identified for patients to be eligible for referral to the CCRC: 1) ≥ 18 years of age, 2) admitted to WMH ICU, and either 3) spent ≥ 48 hours on mechanical ventilation or 4) had delirium for ≥ 48 hours. Patients would also be eligible if their critical care physicians determine that a patient might benefit from a comprehensive physical, cognitive and psychological assessment, and protocol guided therapy. Mechanical ventilation and delirium were selected because of their negative impact on memory, physical function, and psychological outcomes (Desai et al., 2011) and their potential to cause symptoms of PICS. Patients enrolled in hospice or under palliative care services were generally excluded because these patients receive care at home for conditions that prevent comfortable travel to the clinic. The inclusion criteria were ultimately expanded to include referrals from ICUs outside the Wishard Health System on a case-by-case basis.

Outcomes

Below are the four primary outcomes in regards to patient care that our delivery team identified for the CCRC:

Maximize full cognitive, physical and psychological recovery following hospitalization for a critical illness.

Enhance patient and caregiver satisfaction.

Improve the quality of transitional and rehabilitation care.

Reduce inappropriate rehospitalizations and emergency room visits.

Physical Characteristics of CCRC

CCRC is primarily a clinical program with a secondary research focus that is physically located at Wishard Health Services (WHS), a safety net, tax-supported, urban healthcare system in Indianapolis, IN (Boustani et al., 2011). The clinic is in operation one afternoon per week. Within the clinic, there are three patient examination rooms; one family conference room for team discussions about the tailored treatment plan with the patient and their designated caregiver; a work room for interdisciplinary interaction between team-members; a blood collection room, and a work space for documenting the clinical care plans for the patients. The collaborative care team at the CCRC consists of a registered nurse (RN), a critical care physician, a social worker, a medical assistant licensed practical nurse (LPN), and a psychometrician, with support services from physical therapy, neuropsychology, and psychiatry. Both the RN and social worker at CCRC function as care coordinators. Clinic nurses also manage the flow of the clinic, lead family conferences, oversee medication reconciliation, conduct scheduling and follow-up phone calls, and partner with caregivers for stress reduction. A pharmacist is available for consultation about drug reconciliation if needed. Consistent with the mission of WHS who provides funding for the clinic, the CCRC follows a patient-centered care philosophy and a clinical mission of intensifying the recovery of ICU survivors. Although the CCRC has no research funding at this time, standardized manual and electronic assessment plus management and performance data are utilized and readily available for research endeavors.

Operative Characteristics of CCRC

Patient Recruitment

Most patients who come to the CCRC for specialized healthcare are recruited from WMH ICUs. We have used grand rounds, focused provider meetings, physician and patient brochures to enhance patient recruitment and to promote local awareness of the CCRC services. In addition, the CCRCRN and social work care coordinators attended weekly transitional case manager meetings to discuss potential candidates for CCRC referral at the time of their transfer to hospital units outside of the ICU. An ICU nurse practitioner maintains a list of patients that meet CCRC inclusion criteria and refers them to the coordinators promptly. Utilizing our computerized data entry system at WMH, (McDonald et al., 1999) a specific consult order for CCRC was created whereby putting such an order automatically prints out a referral at the center.

Patient Assessment

CCRC has two main patient assessment phases: a) initial assessment and b) follow-up. The CCRC team summarizes patient relevant data during the initial assessment and formulates an individualized care plan for the patient and the care-giver. The follow-up phase is utilized to monitor and modify the implementation of the CCRC individualized care plan based on patients’ and caregivers’ progress.

Phase A. Initial comprehensive assessment and institution of care plan

The process involves the following three steps:

Pre-CCRC visit: A structured patient/caregiver needs assessment via phone or in person at the CCRC if no phone access is available.

CCRC Initial visit: A complete diagnostic work-up including a detailed history, structured physical and neurological examination, a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment (cognitive and psychological), a physical function battery, medication reconciliation, blood tests, and imaging as necessary.

CCRC Follow-up visit: A follow-up family conference involving the nurse, social worker, physician, patient, and caregiver to outline and initiate a personalized, patient centered care plan takes place two weeks after the initial assessment. The discussion entails disclosure of diagnosis and prognosis, clarifying patient/caregiver queries, dispensing self-management training manuals, pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic prescriptions, and proactive referrals to community resources, neuropsychologists and physical rehabilitative services.

Phase B. Follow-Up with Longitudinal Patient Monitoring and Re-Assessment

Frequency of four follow-up visits to CCRC varies depending upon individual patient needs and response to therapy. During these visits, the CCRC team assesses the patient’s cognitive, functional, behavioral and psychological symptoms and their caregiver’s stress and burden through a valid, reliable, clinically practical, multi-dimensional symptom monitoring instrument-the Healthy Aging Brain Center Monitor (HABC-M) (Monahan et al., 2012). The HABC-M is a self or caregiver-reported questionnaire encompassing the last two weeks of a patient’s life, and consisting of 27 items. The items cover three clinical domains associated with cognitive, functional, and behavioral-psychological symptoms with each of the 27 items having four response choices. The choices are not at all (0–1), several days (2–6 days), more than half the days (7–11 days), and almost daily (12–14 days). The four choices are scored from 0 to 3 points, and the total score can range from 0 to 81 with higher scores representing severe symptoms. The individualized care plan is thus modified based on patients’ symptoms and progress.

Patient Characteristics and Performance of CCRC

From July 2011 to May 2012, the CCRC delivered care to 53 new patients during the half-day clinic session per week. Table 2 describes the base-line characteristics of these ICU survivors. The average time of follow-up was at 3 months post hospital discharge. The average age of the patients was 56.6 years (SD 16.3), and females and African Americans represented half of the total number of patients. A significant majority of patients evaluated in the CCRC suffered from cognitive and psychological morbidity with only 6 (11.5%) of the 52 survivors having normal cognition on a standardized comprehensive Cognitive Status Profile, (Unverzagt et al., 1999) which is an expanded and slightly modified version of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s disease (CERAD) neuropsychological battery (Morris, Mohs, Rogers, Fillenbaum, & Heyman, 1988). The domains of cognition tested as part of the CERAD neuropsychological battery were memory, constructional praxis, language, and executive function. If one of the domains was affected, it was classified as a single domain dysfunction, >1 domain as a multi-domain dysfunction; if the affected domains included memory then the diagnoses were classified as amnestic. So for example, if two domains were affected with memory as one of the domains, the disorder would be termed multi-domain amnestic cognitive impairment (CI). On the other hand if memory was not affected, then the disorder would be multi-domain non-amnestic CI. Among patients with CI, 21 (45.6%) had multi-domain amnestic CI; 11 (23.9%) had multi-domain non-amnestic CI; 7 (15.2%) had single domain amnestic CI; 6 (13%) had single domain non-amnestic CI; and one had dementia. Table 3 describes the median scores in the individual neuropsychological tests that constituted the cognitive status profile with lower scores representing cognitive impairment. Up to 58.8% (30/51) of patients exhibited signs of depression on the Geriatric Depression Scale (Yesavage et al., 1982) and 80% of these depressed patients had moderate to severe depression. The median depression scores are presented in Table 3 with higher scores denoting various degrees of depression.

Table 2.

In-hospital Characteristics of Patients evaluated at the Critical Care Recovery Center

| Patients’ Characteristics* (n:53) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 56.6 (16.3) |

| African Americans % | 49.1 |

| Females % | 50.9 |

| Mechanical Ventilation % | 52.8 |

| Mechanical Ventilation duration (days) | 7.0 (6.9) |

| Education | 11.1 (1.7) |

| Charlson’s Chronic Comorbidity Index | 2.3 (2.4) |

| APACHE IIa score | 17.2 (8.3) |

| IQCODEb score | 3.1 (0.3) |

| Activity of Daily Living (Katz scale) | 5.7 (0.7) |

| Instrumental Activity of Daily Living (Lawson scale) | 6.6 (2.3) |

| ICU Location | |

| Medical Intensive Care unit (MICU) % | 77.4 |

| Surgical Intensive Care Unit (SICU) % | 17 |

| Progressive/step-down Intensive Care Unit (PICU) % | 5.6 |

| Delirium durationc (days) | 3.4 (4.4) |

| Coma durationd (days) | 2.9 (4.2) |

| Duration of coma/delirium (days) | 5.8 (7.1) |

| Intensive Care Unit (ICU) length of stay (days) | 17.4 (12.8) |

| Hospital length of stay (days) | 22.8 (14.3) |

| Discharged to home % | 47.2 |

| Discharge diagnoses# n (%) | |

| Acute Respiratory Failure | 17 (32) |

| Sepsis | 10 (18.8) |

| Altered Mental Status | 9 (17) |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease/Asthma | 8 (15) |

| Congestive Heart Failure/Acute Myocardial Infarction | 6 (11.3) |

| Trauma | 3 (5.6) |

| Subdural Hematoma | 2 (3.7) |

| Small Bowel Obstruction | 2 (3.7) |

| Small Bowel Perforation | 2 (3.7) |

| Angioedema | 1 (1.8) |

| Gastrointestinal Bleed | 1 (1.8) |

| Seizures | 1 (1.8) |

| Subarachnoid Hemorrhage | 1 (1.8) |

| Traumatic Brain Injury | 1 (1.8) |

| Meningitis | 1 (1.8) |

| Ventral Hernia Repair | 1 (1.8) |

Variables are presented as mean (standard deviation) unless otherwise specified

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation;

Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly;

as determined by the number of positive CAM-ICU days;

as determined by the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scores (RASS) of −4 and −5

Some of the diagnoses are not mutually exclusive

Table 3.

Scores for Neurocognitive Function constituting the Cognitive Status Profilea,b of Intensive Care Unit Survivors (n: 52)

| Individual Tests | Scores* | Range of Scores† |

|---|---|---|

| Global Mental Status | ||

| • MMSE# | 26(24–28) | 0–30 |

| Language | ||

| • Animal Fluency Test | 15(10–19) | 0–18 |

| • Boston Naming Test | 13(11.75–15) | 0–15 |

| Constructional Praxis | 8(8–10.25) | 0–11 |

| Constructional Praxis Delayed | 7(4–8) | 0–14 |

| Memory | ||

| • Word List Learning Test | ||

| Trial 1 | 3.5(2.75–4.25) | 0–10 |

| Trial 2 | 5(4–7) | 0–10 |

| Trial 3 | 6.5(5–7.25) | 0–10 |

| Delayed Recall | 5(3–6) | 0–10 |

| Recognition Yes | 10(8–10) | 0–10 |

| Recognition No | 10(10–10) | 0–10 |

| Executive Function | ||

| • Trail Making Test A | 39.5(31.75–46.25) | 4–100 |

| • Trail Making Test B | 35(20–45.5) | 4–100 |

| Indiana University Token Test | 23(20–24) | 0–24 |

| Geriatric Depression Scalec | 14(7–21)** | 0–30 |

Scores are presented as median (interquartile range),

The lowest or highest score a patient can achieve on a test. Scores lower than 1 standard deviation represent cognitive impairment. For Geriatric depression scale, scores higher than 1 standard deviation represent depression.

Mini-Mental State Examination

51 values

Adapted from Unverzagt et al., 1999 and Morris, Mohs, Rogers, Fillenbaum, & Heyman, 1988

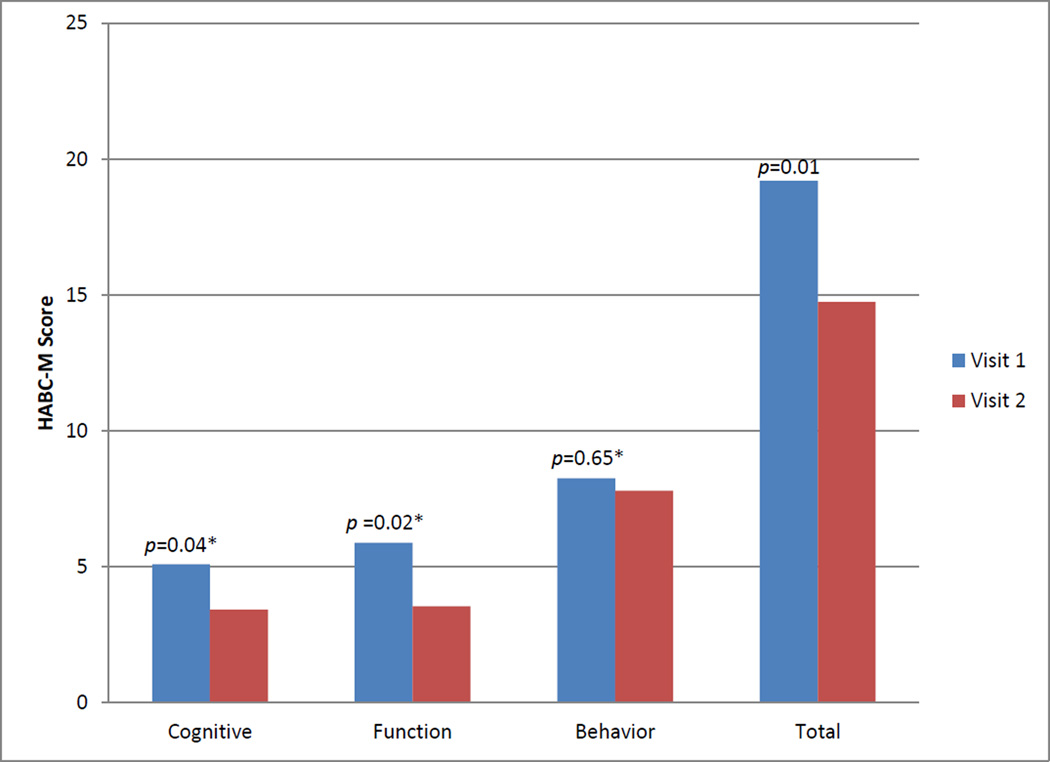

Twenty-four patients in the CCRC had at least two HABC-M scores (Monahan et al., 2012) to compare their functional, cognitive, and psychological symptoms longitudinally. Figure 1 shows the improvement in overall HABC-M scores as reported by patients, as well as the breakdown of patients’ symptoms score into cognitive, functional, and behavioral domains.

Figure 1.

Longitudinal monitoring of patients’ symptoms (n: 24) utilizing the healthy aging brain center monitor (HABC-M)a,b

a Monahan et al., 2012. Total score ranges from 0 to 81points with higher scores representing severe symptoms.

b The average time-period between visit 1 and visit 2 was two and a half months.

Representative CCRC Case Vignette

A 37 year old African American male without prior comorbidities was admitted to WMH ICU for acute respiratory distress syndrome, secondary to E. Coli pneumonia and sepsis. After prolonged mechanical ventilation and ICU stay of 2 weeks, the patient recovered and was discharged to home. He was evaluated in the CCRC three months later where he complained of dyspnea, forgetfulness, and energy deprivation, recurrent episodes of anxiety and out bursts of anger. The patient’s caregiver expressed feelings of depression and helplessness. He received a neuropsychological battery, physical performance battery, and screening for depression and anxiety disorders. Based on the results of these testing, diagnoses of multi-domain amnestic acquired cognitive impairment, major depression and PTSD were made. He was offered cognitive training, problem solving therapy, and a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. In addition, high level of caregiver stress was identified and she was provided a stress self-management manual to learn and practice how to cope with her negative emotions of care giving and was counseled regarding taking time off from care giving. Both the patient and the caregiver were offered regular access to care coordinators.

Discussion

This paper describes the implementation of a novel and innovative collaborative model of care tailored to the emerging needs of patients and caregivers who are suffering from post-intensive care syndrome. Our experience with the CCRC and related preliminary data suggest that there is a role for the interdisciplinary care models to enhance the psychological, cognitive, and physical recovery of ICU survivors. Based on our literature review, the CCRC represents a prototype in United States for providing post ICU care for patients presenting with PICS; the complications acquired secondary to their acute illness. There have been other models of care for ICU survivors including home-based rehabilitation (McWilliams et al., 2009) and nurse-led ICU clinics in United Kingdom, (Cuthbertson et al., 2009) however, prior to our clinic, a collaborative model in the form of a centralized clinic to meet the recovery needs of ICU survivors in United States has not been implemented. The CCRC not only achieves that but it also expands the care to encompass the family caregiver along with the patient. It provides and coordinates care both inside and outside the clinic, going beyond the traditional primary care encounter and thereby offers a distinct solution to decrease the burden associated with critical illness.

Critical illness results in significant long-term complications with a profound impact on the survivor’s quality of life (Davydow et al., 2009; Davydow et al., 2008; Desai et al., 2011; Girard et al., 2010; Herridge, 2009; Needham et al., 2012; Stevens et al., 2007). Intensive care nurses should become aware of the risk factors for PICS and begin to educate family members and others who will provide support after discharge from the hospital. The optimum point for initiating PICS education with those who will assume the caregiver role is when the ICU survivor is nearing discharge from the ICU to acute care. Acute care nurses should continue PICS education during the entire hospital stay so that the caregivers can learn to recognize symptoms, provide support, know when to ask for help, and know when to access the healthcare system (SCCM, 2013).

Although no individual intervention has been demonstrated to be effective in preventing PICS (Melhorn et al., 2014), there are effective nursing interventions for nightmares and sleep disturbance (Cuthbertson et al., 2007). These interventions can be initiated by acute care nurses or by primary care nurses after the survivor is discharged to home. Assisting ICU survivors in keeping a diary of their hospital experiences and returning to the intensive care unit room so the survivor can reframe the sometimes unreal experience into an understanding of what really happened during the ICU stay have been shown to have a positive impact on quality sleep (Cuthbertson et al.). Additionally, recognition of symptoms and seeking care from a provider who is knowledgeable and experienced in PICS should result in better outcomes.

The current demographics of an aging population and improved ICU survival may soon overwhelm the existing health delivery system. The current pace at which new discoveries are translated into clinical practice will not be able to sustain the projected overflow of the system by these ICU survivors; and ultimately the burden will have to be shared by all the stakeholders and the society. To overcome such a scenario, re-engineering of the clinical research enterprise (America, March 2001; Committee on the Future Health Care Workforce for Older Americans, 2008; NIH, 2007) with early translations of innovative research models from discovery to delivery is urgently needed. The implementation of the CCRC at WHS represents one such endeavor where the clinical mission of providing recovery to the ICU survivors in a standardized manner serves to facilitate easy and timely access for research projects. CCRC could serve to be one of the efficient ways to modify the complications post critical illness that in turn could decrease resource utilization. Platforms such as the CCRC could also provide an ideal site for continued investigative efforts to modify and understand the mechanisms responsible for the complications seen in ICU survivors.

Even though we were able to successfully implement the CCRC at Wishard Health Services, we believe that the generalizability of our CCRC may be somewhat limited at other health delivery systems. WHS is a county supported health care system that provides care to underserved and minority populations. This may reduce generalizability to systems and populations different from WHS. With repeated interactions as part of ongoing research projects, our team has developed a strong relationship with the ancillary staff at the ICU which has helped tremendously in patient recruitment for the CCRC. That may not be the case at other institutions, although similar strategies can be initiated at centers involved in conducting research studies in the ICU. WHS has a locally developed comprehensive electronic medical record system (Dexter et al., 2001) that allows direct referrals to the CCRC and captures the data required to evaluate CCRC performance. This may impair the ability of health care systems that do not have the electronic medical record database to provide continuous feedback data to assess the financial and health care impact of similar clinics. The CCRC currently receives financial support from our community partner, the WHS that subsidizes the services rendered to the patients. WHS utilizes the local electronic database to evaluate CCRC performance based on the re-hospitalization rates among ICU survivors. It uses this information to make decisions regarding resource allocation, future planning and the impact of CCRC on the entire system. This may differ from the way other institutions will envision supporting their local ICU survivor clinics and may rely on third party payments.

We believe that in tackling the significant burden of post critical illness physical, psychological, and cognitive morbidity, the CCRC presents a bold and innovative step to modify these PICS symptoms and to improve the ICU survivors’ quality of life. In doing so, it may reduce unnecessary emergency room visits, recurrent hospitalizations, and help to control inflating health care costs. The CCRC prototype serves as a true ahead-of-the-curve example for other health care systems in the US who are interested in instituting similar post-ICU clinics. However, such implementation processes need to be tailored based on the culture of the specific health care system by utilizing the principles of complex adaptive system and the reflective adaptive process.

Side Bar.

| A Complex Adaptive System (Plesk, 1997) |

|

| Reflective Adaptive Process (Stroebel et al., 2005) |

|

References

- I. o. Medicine, editor. American America, I. o. M. C. o. Q. o. H. C. i. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2001. Mar, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RA, Crabtree BF, Steele DJ, McDaniel RR., Jr Case study research: the view from complexity science. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(5):669–685. doi: 10.1177/1049732305275208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angus DC, Carlet J, Brussels Roundtable P. Surviving intensive care: a report from the 2002 Brussels Roundtable. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(3):368–377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1624-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angus DC, Kelley MA, Schmitz RJ, White A, Popovich J, Jr Committee on Manpower for, P., & Critical Care, S. Caring for the critically ill patient. Current and projected workforce requirements for care of the critically ill and patients with pulmonary disease: can we meet the requirements of an aging population? JAMA. 2000;284(21):2762–2770. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.21.2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balas EA, B S. In: Yearbook of Medical Informatics 2000. Bemmel JM, A T, editors. Schattauer GmbH: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Boustani MA, Campbell NL, Khan BA, Abernathy G, Zawahiri M, Campbell T, Callahan CM. Enhancing care for hospitalized older adults with cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(5):561–567. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-1994-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boustani MA, Munger S, Gulati R, Vogel M, Beck RA, Callahan CM. Selecting a change and evaluating its impact on the performance of a complex adaptive health care delivery system. Clin Interv Aging. 2010;5:141–148. doi: 10.2147/cia.s9922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boustani MA, Sachs GA, Alder CA, Munger S, Schubert CC, Guerriero Austrom M, Callahan CM. Implementing innovative models of dementia care: The Healthy Aging Brain Center. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(1):13–22. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.496445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Unverzagt FW, Austrom MG, Damush TM, Perkins AJ, Hendrie HC. Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer disease in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(18):2148–2157. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.18.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Weiner M, Beck RA, Livin LR, Kellams JJ, Hendrie HC. Implementing dementia care models in primary care settings: The Aging Brain Care Medical Home. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(1):5–12. doi: 10.1080/13607861003801052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell NL, Khan BA, Farber M, Campbell T, Perkins AJ, Hui SL, Boustani MA. Improving delirium care in the intensive care unit: the design of a pragmatic study. Trials. 2011;12:139. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D, McDaniel RR, Jr, Crabtree BF, Ruhe MC, Weyer SM, Tallia A, Stange KC. A practice change model for quality improvement in primary care practice. J Healthc Manag. 2004;49(3):155–168. discussion 169–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on the Future Health Care Workforce for Older Americans, I. o. M. o. t. N. A. Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Stange KC. Understanding practice from the ground up. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(10):881–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbertson BH, Rattray J, Campbell MK, Gager M, Roughton S, Smith A group, P. R. s. The PRaCTICaL study of nurse led, intensive care follow-up programmes for improving long term outcomes from critical illness: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;339:b3723. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davydow DS, Gifford JM, Desai SV, Bienvenu OJ, Needham DM. Depression in general intensive care unit survivors: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(5):796–809. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1396-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davydow DS, Gifford JM, Desai SV, Needham DM, Bienvenu OJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder in general intensive care unit survivors: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(5):421–434. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai SV, Law TJ, Needham DM. Long-term complications of critical care. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(2):371–379. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181fd66e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dexter PR, Perkins S, Overhage JM, Maharry K, Kohler RB, McDonald CJ. A computerized reminder system to increase the use of preventive care for hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(13):965–970. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa010181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egerod I, Risom SS, Thompsen T, Storli SL, Eskerud RS, Holme AN, Samuelson KAM. ICU-recovery in Scandinavia: A comparative study of intensive care follow-up in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Intensive and critical care nursing. 2013;29:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard TD, Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Pun BT, Thompson JL, Shintani AK, Ely EW. Delirium as a predictor of long-term cognitive impairment in survivors of critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(7):1513–1520. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e47be1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Group DW. Conducting the Direct Observation of Primary Care Study. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(4):345–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herridge MS. Legacy of intensive care unit-acquired weakness. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(10 Suppl):S457–S461. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b6f35c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden LM. Complex adaptive systems: concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(6):651–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint. Commission. Resources. Improving Care in the ICU. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lansing S. Complex adaptive systems. Annu Rev Anthropol. 2003;32:183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews JI, Thomas PT. Managing clinical failure: a complex adaptive system perspective. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2007;20(2–3):184–194. doi: 10.1108/09526860710743336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel RR, Jr, Jordan ME, Fleeman BF. Surprise, Surprise, Surprise! A complexity science view of the unexpected. Health Care Manage Rev. 2003;28(3):266–278. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200307000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald CJ, Overhage JM, Tierney WM, Dexter PR, Martin DK, Suico JG, Wodniak C. The Regenstrief Medical Record System: a quarter century experience. Int J Med Inform. 1999;54(3):225–253. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(99)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams DJ, Atkinson D, Carter A, Foex BA, Benington S, Conway DH. Feasibility and impact of a structured, exercise-based rehabilitation programme for intensive care survivors. Physiother Theory Pract. 2009;25(8):566–571. doi: 10.3109/09593980802668076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlhorn J, Freytag A, Schmidt K, Brunkhorst FM, Graf J, et al. Rehabilitation Interventions for Postintensive Care Syndrome: A Systematic Review, Critical Care Medicine. 2014;42(5):1263–1271. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan PO, Boustani MA, Alder C, Galvin JE, Perkins AJ, Healey P, Callahan C. Practical clinical tool to monitor dementia symptoms: the HABC-Monitor. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:143–157. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S30663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC, Mohs RC, Rogers H, Fillenbaum G, Heyman A. Consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer's disease (CERAD) clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24(4):641–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needham DM, Bronskill SE, Calinawan JR, Sibbald WJ, Pronovost PJ, Laupacis A. Projected incidence of mechanical ventilation in Ontario to 2026: Preparing for the aging baby boomers. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(3):574–579. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000155992.21174.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, Hopkins RO, Weinert C, Wunsch H, Harvey MA. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders' conference. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2):502–509. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIH. NIH Roadmap for Clinical Research: Clinical Research Network and NECTAR 2007. 2007 from http://nihroadmap.nih.gov.

- Plesk. Working Paper: Some Emerging Principles for Managing in Complex Adaptive Systems; 1997. [Retrieved November 5, 1997]. from http://www.directedcreativity.com/pages/ComplexityWP.html#CAS. [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein LV, Pugh J. Strategies for promoting organizational and practice change by advancing implementation research. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 2):S58–S64. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00364.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCCM. Critial Care Units: A Descriptive Analysis. 1st ed. Des Plaines, IL: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- SCCM. Post Intensive Care Syndrome. [Retrieved 17 April 2014];2013 from http://www.myicucare.org/Adult-Support/Pages/Post-intensive-Care-Syndrome.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Spragg RG, Bernard GR, Checkley W, Curtis JR, Gajic O, Guyatt G, Harabin AL. Beyond mortality: future clinical research in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(10):1121–1127. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0024WS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens RD, Dowdy DW, Michaels RK, Mendez-Tellez PA, Pronovost PJ, Needham DM. Neuromuscular dysfunction acquired in critical illness: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(11):1876–1891. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0772-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebel CK, McDaniel RR, Jr, Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Nutting PA, Stange KC. How complexity science can inform a reflective process for improvement in primary care practices. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2005;31(8):438–446. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(05)31057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unverzagt FW, Morgan OS, Thesiger CH, Eldemire DA, Luseko J, Pokuri S, Hendrie HC. Clinical utility of CERAD neuropsychological battery in elderly Jamaicans. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1999;5(3):255–259. doi: 10.1017/s1355617799003082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickrey BG, Mittman BS, Connor KI, Pearson ML, Della Penna RD, Ganiats TG, Lee M. The effect of a disease management intervention on quality and outcomes of dementia care: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(10):713–726. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, Leirer VO. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]