Abstract

Extensive structure activity relationship (SAR) studies focused on the desferrithiocin [DFT, (S)-4,5-dihydro-2-(3-hydroxy-2-pyridinyl)-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic acid] pharmacophore have led to three different DFT analogues being evaluated clinically for the treatment of iron overload diseases, e.g., thalassemia. The SAR work revealed that the lipophilicity of a ligand, as determined by its partition between octanol and water, log Papp, could have a profound effect on the drug’s iron clearing efficiency (ICE), organ distribution, and toxicity profile. While within a given structural family the more lipophilic a chelator the better the ICE, unfortunately, the more lipophilic ligands are often more toxic. Thus, a balance between lipophilicity, ICE, and toxicity must be achieved. In the current study, we introduce the concept of “metabolically programmed” iron chelators, i.e., highly lipophilic, orally absorbable, effective deferration agents which, once absorbed, are quickly converted to their nontoxic, hydrophilic counterparts.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Nearly all life forms require iron as a nutrient [1]. However, the low solubility of Fe(III) hydroxide, the predominant form of the metal in the biosphere [2], necessitated the development of sophisticated iron storage and transport systems by both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Microorganisms utilize low molecular weight, ferric iron-specific ligands, siderophores [3–7]; eukaryotes tend to employ proteins to transport and store iron [8,9]. Humans have developed a highly efficient iron management system [10] in which we absorb and excrete only about 1 mg of the metal daily; there is no mechanism for the excretion of excess iron [11]. Disruption of this homeostasis can lead to severe consequences, even lethal events.

Whether derived from transfused red blood cells [12,13], required in the treatment of hemolytic anemias, or from increased absorption of dietary iron [14], without effective treatment, iron deposition occurs in the liver, heart, pancreas, and elsewhere [15]. This can lead to liver disease [16], diabetes [17], increased risk of cancer [18], and heart disease, often the cause of death in these patients [19]. The nontransferrin-bound plasma iron (NTBIa) [20–22] pool, a still somewhat ill defined pool of the metal, is the origin of the organ damage that develops with iron overload.

The toxicity associated with excess iron derives from its interaction with reactive oxygen species, for instance, endogenous hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [23–25]. In the presence of Fe(II), H2O2 is reduced to the hydroxyl radical (HO•) and HO−, a process known as the Fenton reaction. The hydroxyl radical reacts very quickly with a variety of cellular constituents and can initiate radical-mediated chain processes that damage DNA and membranes, as well as produce carcinogens [26]. The cyclic nature of the Fenton reaction adds to the potential danger. The Fe(III) liberated in this reaction is converted back to Fe(II) via a variety of biological reductants, e.g., ascorbate or glutathione.

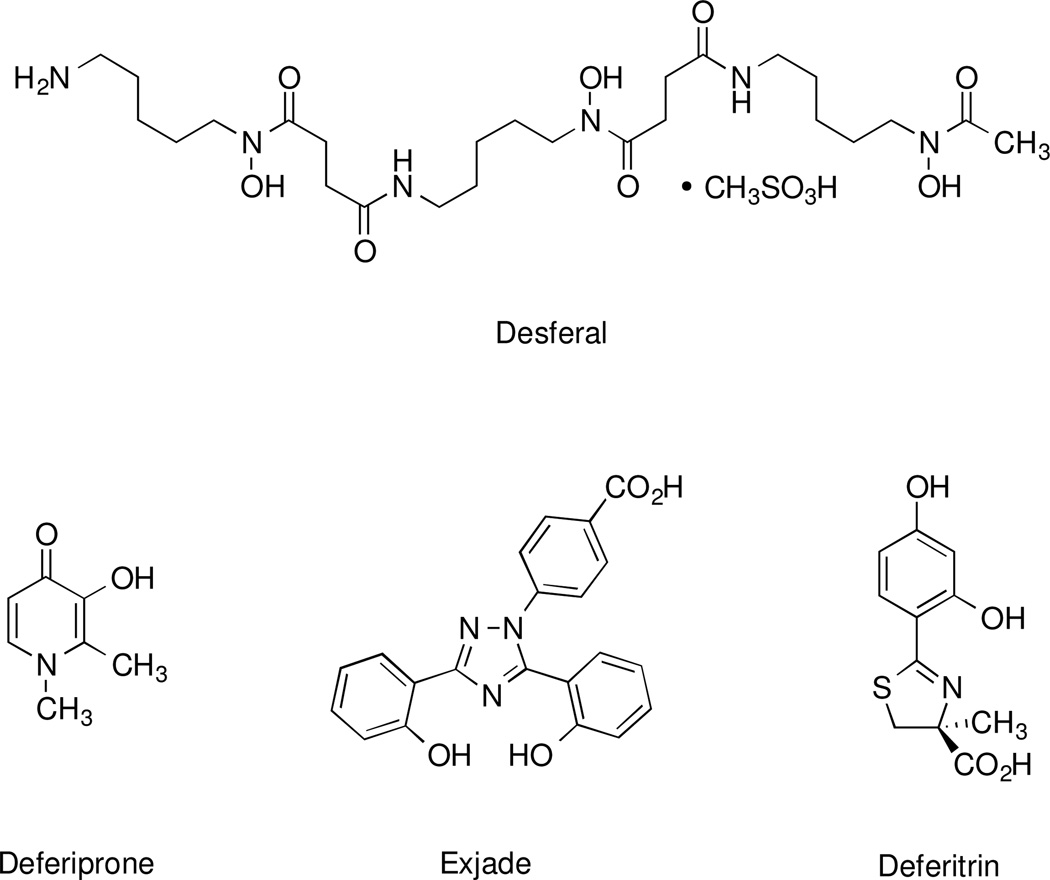

In the majority of patients with thalassemia major or other transfusion-dependent refractory anemias, treatment with a chelating agent capable of sequestering iron and permitting its excretion from the body is the only therapeutic option available. Current choices (Figure 1) include Desferal, the mesylate salt [27] of desferrioxamine B (DFO), 1,2-dimethyl-3-hydroxypyridin-4-one (deferiprone, L1) [28,29], and 4-[3,5-bis(2-hydroxyphenyl)-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl]benzoic acid (deferasirox, ICL670A) [30,31]. Each presents with palpable shortcomings [32] and in some cases, serious toxicity issues. DFO, a hexacoordinate hydroxamate iron chelator produced by Streptomyces pilosus [33], a siderophore, is not orally active and is best administered subcutaneously (sc) by continuous infusion over long periods of time [34], a patient compliance issue. Deferiprone, while orally active, does not remove enough iron to keep patients in a negative iron balance and has been associated with agranulocytosis [35]. The Novartis drug deferasirox did not show noninferiority to DFO, is associated with a number of serious side effects, and, unfortunately, has a narrow therapeutic window [31,36].

Figure 1.

Structures of some of the iron chelators evaluated clinically in humans.

Our pursuit of an efficient orally active iron chelator with an acceptable toxicity profile began with desferrithiocin, (S)-4,5-dihydro-2-(3-hydroxy-2-pyridinyl)-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic acid (DFT, 1, Table 1). DFT is a tridentate siderophore [37,38] excreted by Streptomyces antibioticus [37] that forms a stable 2:1 complex with Fe(III); the cumulative formation constant is 4 × 1029 [38]. Initial animal trials with DFT in rodents [39] and primates [40–42] revealed it to be orally active and highly efficient at removing iron. Its iron clearing efficiency (ICE) was 5.5 ± 3.2% in rodents [39], and 16.1 ± 8.5% in primates [41] (Table 1). ICE is calculated as (ligand-induced iron excretion/theoretical iron excretion) × 100, expressed as a percent. However, DFT presented with unacceptable renal toxicity in rats [43,44]. Nevertheless, the ligand’s remarkable oral bioavailability and ICE drove a very successful structure-activity study aimed at ameliorating DFT-induced nephrotoxicity [40,45–48]. The outcome revealed that removal of the desferrithiocin aromatic nitrogen, providing (S)-4,5-dihydro-2-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic acid (desazadesferrithiocin, DADFT), and introduction of a hydroxyl at either the 4'-aromatic to yield (S)-2-(2,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydro-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic acid [40] [(S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT, deferitrin, 2] or the 3'-aromatic to afford (S)-2-(2,3-dihydroxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydro-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic acid [40] [(S)-3'-(HO)-DADFT, 3] led to chelators with good ICE values (Table 1) and a remarkable reduction in toxicity. Deferitrin (2, Figure 1), was taken into human clinical trials by Genzyme. Ligand 2 was well tolerated in patients at doses of 5, 10, or 15 mg/kg/day once daily (s.i.d) for up to 12 weeks [49], and iron clearance levels were approaching the requisite 450 µg/kg/d [50]. However, when the drug was given twice daily (b.i.d) at a dose of 12.5 mg/kg (25 mg/kg/d), unacceptable renal toxicity, i.e., increases in blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine (SCr), were observed in three patients after only 4–5 weeks of treatment and the study was terminated [51]. Nevertheless, the results were attractive enough to compel us to reengineer deferitrin in an attempt to ameliorate the b.i.d. toxicity.

Table 1.

Iron Clearing Efficiency of Iron Chelators given to Rats and Cebus apella Primates, and the Log Papp of the Compounds

| Compound | Route |

aLog Papp |

bRodent ICE (%) |

dPrimate ICE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

sc | < −3.2 | 2.5 ± 0.7 [74/26] |

5.5 ± 0.9 [45/55] |

|

po | −1.77 | 5.5 ± 3.2 [93/7] |

16.1 ± 8.5 [78/22] |

|

po | −1.05 | 1.1 ± 0.8 [100/0] |

16.8 ± 7.2 [88/12] |

|

po | −1.17 | 4.6 ± 0.9 [98/2] |

23.1 ± 5.9 [83/17] |

|

po | −0.70 | 6.6 ± 2.8 [98/2] |

24.4 ± 10.8 [91/9] |

|

po | −1.10 | 5.5 ± 1.9 [90/10] |

25.4 ± 7.4 [96/4] |

|

po | −1.22 | 10.6 ± 4.4c [95/5] |

23.0 ± 4.1 [95/5] |

|

po | −0.89 | 26.7 ± 4.7c [97/3] |

26.3 ± 9.9e [93/7] |

| 28.7 ± 12.4f [83/17] |

||||

Data are expressed as the log of the fraction of the chelator seen in the octanol layer (log Papp); measurements were done in TRIS buffer, pH 7.4, using a “shake flask” direct method.

In the rodents n= 3 (7), 4 (3–6), 5 (1), 6 (DFO) or 8 (2). The drugs were given orally (po) or subcutaneously (sc) as indicated in the table at a dose of 150 (DFO and 1) or 300 µmol/kg (2–7) The drugs were solubilized in 40% Cremophor RH-40/water (DFO and 1), distilled water (5), administered in capsules (7), or were given as their monosodium salts, prepared by the addition of 1 equiv of NaOH to a suspension of the free acid in distilled water (2–4, 6). The efficiency of each compound was calculated by subtracting the iron excretion of control animals from the iron excretion of the treated animals. The number was then divided by the theoretical output; the result is expressed as a percent.

ICE is based on a 48 h sample collection period. The relative percentages of the iron excreted in the bile and urine are in brackets.

In the primates n= 3 (6), 4 (1, 3–5, 7 in capsulesd), 5 (DFO), or 7 (2, 7 as its monosodium salte). The chelators were given po or sc at a dose of 75 (7) or 150 µmol/kg (DFO, 1–6). The ligands were solubilized in 40% Cremophor RH-40/water (1, 3, 4), distilled water (DFO, 5), administered in capsules (7d), or were given as their monosodium salts, prepared by the addition of 1 equiv of NaOH to a suspension of the free acid in distilled water (2, 6, 7 f). The ICE was calculated by averaging the iron output for 4 days before the drug, subtracting these numbers from the 2-day iron clearance after the administration of the drug, and then dividing by the theoretical output; the result is expressed as a percent. The relative percentages of the iron excreted in the feces and urine are in brackets.

The redesign of 2 was predicated on the observation that both ligands 2 and 3 were orally active iron chelators in rodents and primates (Table 1), and that when the 4'-(OH) of 2 was methylated, providing (S)-4,5-dihydro-2-(2-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic acid [46] [(S)-4'-(CH3O)-DADFT, 4], there was a remarkable enhancement in both ICE and lipophilicity (log Papp). The log Papp data are expressed as the log of the fraction of the chelator seen in the octanol layer; measurements were done in TRIS buffer, pH 7.4, using a “shake flask” direct method [52]. The more negative the log Papp, the less chelator is in the octanol phase, the less lipophilic. Unfortunately, the increase in ICE of 4 came with a concomitant increase in toxicity [53]. Thus, the delicate balance between the increase in ICE and toxicity with enhanced lipophilicity needed to be understood and exploited. Ultimately, it was determined that introducing polyether fragments at the 4'-(OH) of 2 to produce (S)-4,5-dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(3,6,9-trioxadecyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic acid [53] [(S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT-PE, 5] or the 3'-(OH) of 3, yielding (S)-4,5-dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-3-(3,6,9-trioxadecyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic acid [54] [(S)-3'-(HO)-DADFT-PE, 6] led to less lipophilic, i.e., lower log Papp, remarkably efficient iron chelators (Table 1). Unlike deferitrin, there was no renal toxicity seen with either 5 or 6, even when the molecules were administered b.i.d. [53–55].

A magnesium salt of ligand 6 (SPD602, deferitazole magnesium, CAS # 1173092-59-5) was evaluated in clinical trials by Shire [56,57]. Since 6 is an oil, and its sodium salt is hygroscopic, dosage form issues may have driven their choice of a magnesium salt. It is interesting to speculate as to whether or not the gastrointestinal (GI) and other side effects observed with the magnesium salt of 6 [56,57] derive from the magnesium itself [58–60]. All of our studies with 6 were conducted with the monosodium salt [54,55,61]. It remains to be seen how well the magnesium salt will perform in patients.

There were, in fact, two properties of the (S)-3'-(HO)-DADFT-PE (6) that needed attention. The parent drug was an oil, and the dose response curve in rats plateaued very quickly. For example, when 6 was given po to bile duct-cannulated rats at a dose of 150 µmol/kg, the drug decorporated 0.782 ± 0.121 mg/kg of iron; the ICE was 18.7 ± 2.9% [48,61]. However, when the dose of the chelator was further increased to 300 µmol/kg, the quantity of iron excreted, 0.887 ± 0.367 mg/kg, was within error of that induced by the drug at 150 µmol/kg (p > 0.05), and the ICE was 10.6 ± 4.4% [48,61]. Thus, the deferration induced by 6 was saturable over a fairly narrow dose range. Additional SAR studies were carried out to search for a chelator that had better physiochemical properties, i.e., a solid that retained its ICE over a wider range of doses. The answer would come with a simple structural modification of (S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT-PE (5): the 3,6,9-trioxadecyloxy polyether moiety was replaced with a 3,6-dioxaheptyloxy function, providing (S)-4,5-dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(3,6-dioxaheptyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic acid [61,62] [(S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT-norPE, 7]. Both acid 7 (Table 1) and its ester precursor [62] were crystalline solids and could be given very effectively in capsules to both rodents and primates. Ligand 7 has excellent ICE properties (~26%) in rodents and primates. It also has a much better dose response in rodents than 6 [61].

Because of the problems with b.i.d. deferitrin, the toxicity issue of most concern with 7, was, of course, related to renal proximal tubule damage. A series of tolerability studies focusing on (S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT-norPE’s impact on renal function were carried out in rodents [61]. The drug was given po to rats s.i.d. for 28 d (56.9, 113.8, or 170.7 µmol/kg/day); s.i.d. for 10 d (384 µmol/kg/d), and b.i.d. at 237 µmol/kg/dose (474 µmol/kg/d) × 7 d [61]. Blood was collected immediately prior to sacrifice and was submitted for a complete blood count (CBC) and serum chemistries, including the determination of the animals’ blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine (SCr). No drug-related abnormalities were found, and the rats’ BUN and SCr levels were within the normal range [62]. In addition, an assessment of the drug’s effect on urinary kidney injury molecule-1 (Kim-1) [63,64] excretion was determined. Kim-1 is a type 1 transmembrane protein located in the epithelial cells of proximal tubules [63,64]. The ectodomain of the Kim-1 proximal tubule protein is released into the urine very early after exposure to a nephrotoxic agent or ischemia; it appears far sooner than increases in BUN or SCr are detected in the serum [65,66]. Administration of 7 to rats for up to 28 d did not elicit any increases in urinary Kim-1 excretion [61]. Extensive tissues were submitted for histopathology; no drug-related abnormalities were identified. Chelator 7 was recently licensed by Sideris Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and is moving forward in clinical trials. This SAR success set the stage for a closer look at how best to further exploit the relationship between lipophilicity, ICE, and ligand toxicity. The design strategies would weigh heavily on how a chelator’s substituents are metabolized.

2. Results And Discussion

2.1 Design Concept

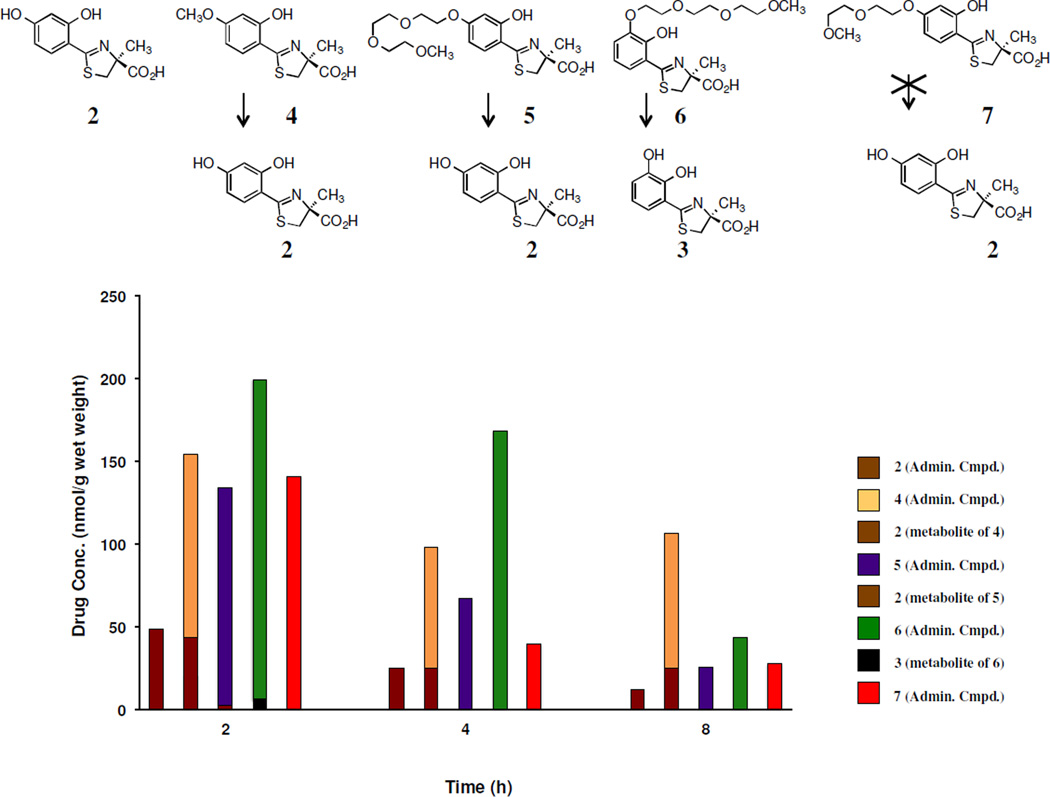

The concept is fairly simple: fix a lipophilic fragment to a chelator that will promote its GI absorption. Once absorbed, it should be quickly converted to its hydrophilic, nontoxic counterpart. The metabolic profiles of the current chelators will thus set the structural boundary conditions for the future design strategies. Early metabolic studies with (S)-4'-(CH3O)-DADFT (4), in which the ligand was given sc to rats at a dose of 300 µmol/kg, revealed that it was demethylated in the liver [67], producing (S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT (2, Figure 2) [45]. At 2 h post drug exposure, about 30% of the (S)-4'-(CH3O)-DADFT (4) is demethylated to 2, and the metabolite remains at fairly high levels through the 8-h time point (Figure 2). This observation encouraged a similar assessment of the polyethers (S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT-PE (5) and (S)-3'-(HO)-DADFT-PE (6). If, for example, 5 were converted to 2 to any great extent, this would preclude it being given b.i.d. as renal toxicity might be expected over a long-term exposure. The lack of toxicity of 5 and 6, even when given b.i.d., suggests that cleavage to 2 was either absent or very modest. Accordingly, chelators 5 and 6 were given to rats sc at a dose of 300 µmol/kg. The tissues that were evaluated included the plasma, liver, kidney, heart, and pancreas. The only organ that presented with any 4'- or 3'- polyether cleavage was the liver (Figure 2). At 2 h, 2% of 5 was converted to 2, and 2.6% of 6 was metabolized to the corresponding 3. The metabolites were not detected at the 4 and 8 h time points [48]. This was not surprising. When 7 was given sc to rats under the same experimental protocol as described for 5 and 6, there was no cleavage to 2 (Figure 2). However, based on studies with other drugs, e.g., glycodiazine, in which polyether fragments were appended [68–72], we were compelled to determine whether or not the terminal methyl of 7 was being cleaved.

Figure 2.

Tissue metabolism/distribution of DADFT analogues 2 and 4–7 in rat liver. The rats (n=3 per group) were given the drugs sc at a dose of 300 µmol/kg. The chelator concentration data (y-axis) are expressed as nmol/g wet weight.

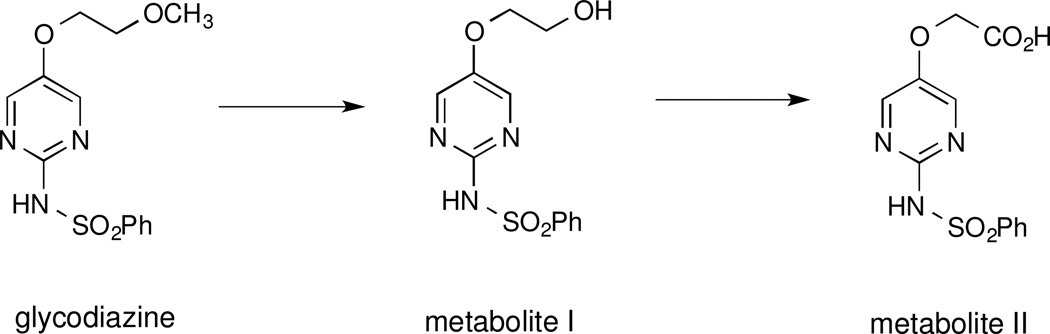

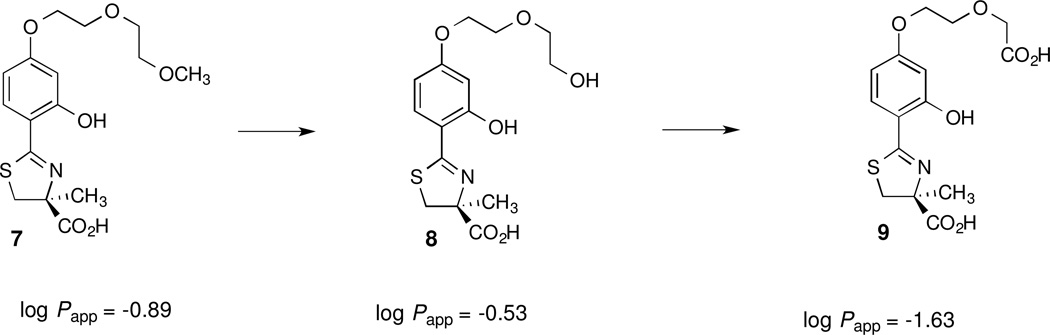

With glycodiazine (Figure 3) the methyl ether was dealkylated to an alcohol (metabolite I), which was oxidized to a carboxylic acid (metabolite II) [70]. If this were the case with 7, for example, this would lead first to the corresponding alcohol (S)-4,5-dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(5-hydroxy-3-oxapentyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic acid [(S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT-PEA, 8] and then to the acid (S)-4,5-dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(4-carboxy-3-oxabutyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic acid [(S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT-PEAA, 9], Figure 4. Both of these metabolic products would be expected to be very hydrophilic. This increase in hydrophilicity, based on previous studies, would further be expected to minimize ligand toxicity [40,46,48]. If indeed such a demethylation-oxidation scenario is occurring with 7, it could support an innovative approach to “metabolically programmed” iron chelators, i.e., highly lipophilic, orally absorbable ligands that are quickly converted to hydrophilic, likely nontoxic metabolites.

Figure 3.

Dealkylation of the methyl ether of glycodiazine, first to an alcohol (metabolite I), which is then oxidized to a carboxylic acid (metabolite II).

Figure 4.

The structures of the putative metabolites of 7, 8 and 9, and the lipophilicity (log Papp) of the ligands.

The two putative metabolites of (S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT-norPE (7), the alcohol (S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT-PEA (8) and the carboxylic acid (S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT-PEAA (9), were assembled. These two synthetic chelators allowed us to develop an analytical high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) method to follow the potential conversion of 7 to its metabolites in the organs of animals treated with the parent chelator 7. Furthermore, it provided an opportunity to evaluate the lipophilicity (log Papp), and the ICE values of 8 and 9 when the chelators were given to the rats and primates po and/or sc.

2.2 Synthesis of 8 and 9

Assembly of alcohol 8 and the carboxylic acid 9 (Scheme 1) began with alkylation of deferitrin ethyl ester (15) at the 4'-hydroxyl [55]. Specifically, reaction of 15 with 2-(2-chloroethoxy)ethanol (16), K2CO3 and KI in DMF at 100 °C provided the alcohol ester 17 in 62% yield. Treatment of 17 with 50% NaOH in CH3OH led to the alcohol 8 in 97% yield. Alkylating 15 with ethyl 2-chloroethoxyacetate (18) [73] under the above conditions gave the diester 19 in 35% yield. Saponification of 19 furnished the diacid 9 as its monosodium salt in 98% yield.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of (S)-4,5-Dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(5-hydroxy-3-oxapentyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic Acid (8) and (S)-4,5-Dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(4-carboxy-3-oxabutyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic Acid (9)a

aReagents and conditions: (a) K2CO3 (2.0 equiv), KI, DMF, 100 °C, 1 d, 62%; (b) K2CO3 (2.1 equiv), NaI, DMF, 95 °C, 22 h, 35%; (c) 50% NaOH (aq), CH3OH, 97% (8), 98% (9 as its monosodium salt).

2.3 Tissue Distribution/Metabolism of (S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT-norPE (7)

As described above, when 7 was given sc to rats at a dose of 300 µmol/kg, there was no cleavage to 2 (Figure 2). When the tissues were subjected to further analysis via HPLC for the presence of 8 or 9, cleavage of the terminal methyl of 7 to the corresponding alcohol 8 did occur (Figure 5). However, carboxylic acid 9 was not detected, probably because the extent of the metabolism of the parent 7 to 8 was so minor. However, when synthetic alcohol 8 was given sc to rats, it was very efficiently converted to acid 9.

Figure 5.

Tissue metabolism/distribution of DADFT analogues 7 and synthetic 8 in rat plasma, liver, kidney, heart and pancreas. The rats (n=3 per group) were given the drugs sc at a dose of 300 µmol/kg. The chelator concentration data (y-axis) are expressed as nmol/g wet weight, or µM (plasma).

Rodents were administered synthetic alcohol 8 sc at a dose of 300 µmol/kg. The rats were euthanized 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 h post drug. The animals’ plasma, liver, kidney, heart and pancreas were removed and assessed for the presence of 8 and its putative metabolite 9. The extent and rapidity of oxidation of 8 to 9 that unfolded was surprising (Figure 5). In the plasma at 0.5 h post drug, nearly 60% of 8 had been converted to 9. At 2 h post dosing, 88% of the drug is in the form of the metabolite. Neither the parent 8 nor the metabolite 9 was found at the 8 h time point. A similar story unfolds in the liver (Figure 5). At 0.5 h post drug, only 53% of the drug (parent + metabolite) is in the form of the parent 8. At 1 h, the metabolite 9 comprises 59% of the total. The parent vs metabolite ratio is similar at the 2 and 4 h time points. At 8 h, very little parent alcohol 8 and no metabolite 9 remains. The kidney, heart and pancreas also demonstrated a similar and significant conversion of 8 to 9 (Figure 5). These findings set the stage for an innovative approach to metabolically programmed ligands. The question, then, became would such alcohols and acids represent useful chelators, with good ICEs and no toxicity issues?

2.4 Chelator-Induced Iron Clearance of 2 and 7–9 in Non-Iron-Overloaded, Bile Duct-Cannulated Rodents

The ICE values for compounds 2 and 7 (Table 2) are historical and included for comparative purposes. The chelators were given to the rats po at a dose of 300 µmol/kg; 9 was also given sc at the same dose. Compound 2 (log Papp = −1.05) was the least effective ligand, with an ICE of 1.1 ± 0.8% [53]. Analogue 7 (log Papp = −0.89) was the most effective, with an ICE of 26.7 ± 4.7% [62]. Ligands 8 (log Papp = −0.53) and 9 (log Papp = −1.63), the two putative metabolites of 7, were significantly less active than the parent drug 7 when given po. The ICE of 8 was 15.4 ± 5.6% (p < 0.02), while the ICE of 9 was and 6.2 ± 1.7% (p < 0.005). As ligand 9 is very hydrophilic (log Papp = −1.63) the lack of activity on po administration was likely due to its poor oral absorption. Indeed, when 9 was given to the rats sc at a dose of 300 µmol/kg, its ICE, 11.3 ± 3.4%, was nearly twice that when the drug was dosed po (p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Iron Clearing Efficiency of Iron Chelators given to Rats and Cebus apella Primates, and the Log Papp of the Compounds

| Compound | Log Papp |

bRat ICE (%) [bile/urine] |

Rat n= |

dCebus ICE (%) [bile/urine] |

Primate n= |

gPerformance Ratio (PR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

−1.05 | 1.1 ± 0.8 [100/0] |

8 | 16.8 ± 7.2 [88/12] |

7 | 15.3 |

|

−0.89 | 26.7 ± 4.7c [97/3] |

3 | 26.3 ± 9.9e [93/7] |

4 | 1.0 |

| 28.7 ±12.4f [83/17] |

6 | 1.1 | ||||

|

−0.53 | 15.4 ± 5.6 [98/2] |

8 | 9.8 ± 3.4 [54/46] |

4 | 0.6 |

|

−1.63 | 6.2 ± 1.7 (po) [100/0] |

3 | 1.7 ± 1.4 (po) [51/49] |

4 | 0.3 |

| 11.3 ± 3.4 (sc) [99/1] |

3 | 17.4 ± 9.7 (sc) [84/16] |

4 | 1.5 | ||

|

0.95 | 15.8 ± 3.7 (po) [99/1] |

4 | Toxic in Rats | ||

|

0.21 | 9.9 ± 0.8 (po) [96/4] |

4 | 21.9 ± 3.6 (po) [90/10] |

3 | 2.2 |

|

−1.90 | 8.8 ± 1.8 (po) [94/6] |

5 | 10.6 ± 4.0 (po) [82/18] |

4 | 1.2 |

| 6.5 ± 1.5 (sc) [96/4] |

4 | 18.8 ± 8.7 (sc) [69/31] |

4 | 4.4 | ||

|

−2.21 | 3.7 ± 1.7 (po) [89/11] |

5 | 5.4 ± 1.5 (po) [97/3] |

4 | 1.5 |

| 4.3 ± 1.1 (sc) [95/5] |

4 | 18.1 ± 7.5 (sc) [78/22] |

4 | 4.2 | ||

|

−1.98 | 2.6 ± 1.6 (po) [89/11] |

3 | 3.0 ± 2.7 (po) [60/40] |

4 | 1.2 |

| 6.0 ± 1.9 (sc) [94/6] |

3 | 15.9 ± 4.3 (sc) [53/47] |

4 | 2.7 | ||

Data are expressed as the log of the fraction of the chelator seen in the octanol layer (log Papp); measurements were done in TRIS buffer, pH 7.4, using a “shake flask” direct method.

In the rodents the drugs were given po or sc at a dose of 300 µmol/kg. The drugs were administered in capsules (7), or were given as their monosodium salts, prepared by the addition of 1 equiv of NaOH to a suspension of the free acid in distilled water (2, 8–14). The efficiency of each compound was calculated by subtracting the iron excretion of control animals from the iron excretion of the treated animals. The number was then divided by the theoretical output; the result is expressed as a percent.

ICE is based on a 48 h sample collection period. The relative percentages of the iron excreted in the bile and urine are in brackets.

In the primates the chelators were given po or sc at a dose of 75 µmol/kg (7–9, 11–14) or 150 µmol/kg (2). The drugs were administered in capsules (7 e), or were given as their monosodium salts, prepared by the addition of 1 equiv of NaOH to a suspension of the free acid in distilled water (2, 7 f–9, 11–14). The efficiency was calculated by averaging the iron output for 4 days before the drug, subtracting these numbers from the 2-day iron clearance after the administration of the drug, and then dividing by the theoretical output; the result is expressed as a percent. The relative percentages of the iron excreted in the feces and urine are in brackets.

Performance ratio (PR) is defined as the mean ICEprimates/ICErodents.

2.5 Chelator-Induced Iron Clearance of 2 and 7–9 in Iron-Overloaded Primates

The primate iron clearance data are provided in Table 2. The ICE values for compounds 2 and 7 are historical and included for comparative purposes. The chelators were given to the monkeys po at a dose of 75 (7–9) or 150 µmol/kg (2); 9 was also given to the primates sc at a dose of 75 µmol/kg. The ICE of ligand 2 was 16.8 ± 7.2% [53]. As with the rats, compound 7 was the most effective iron decorporation agent, with an ICE of 26.3 ± 9.9% when it was given po in capsules, and an ICE of 28.7 ± 12.4% when it was administered po as its monosodium salt [62]. Although 8, the putative metabolite of 7, is more lipophilic than 7, log Papp = −0.53 vs −0.89, its ICE was lower, 9.8 ± 3.4% (p < 0.003, Table 2). The ICE of 9 given po was even lower, only 1.7 ± 1.4%. When 9 was administered sc to the same group of monkeys that had been given the drug po, the ICE increased by more than 10-fold, to 17.4 ± 9.7% (p < 0.03). This is in keeping with the idea that highly charged ligands like 9 (log Papp = −1.63) do not make it across the intestinal mucosa, but hydrophilic metabolic precursors do.

2.6 Metabolically Programmed Iron Chelators

The design of metabolically programmed iron chelators is thus derived from the observation that alcohol 8 is very efficiently oxidized to carboxylic acid 9 (Figure 4 and 5). The corollary to all of this is that the replacement of the 3,6-dioxaheptyl group of the parent polyether (S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT-norPE (7) with a long chain alcohol should provide a highly lipophilic chelator with good po absorption. Once absorbed, the ligand is likely to be metabolized to its less lipophilic, less toxic acid counterparts. This metabolic programming may offer an innovative way to exploit the delicate balance seen between enhanced chelator lipophilicity and ICE, and ameliorate the concomitant increase in toxicity usually associated with increases in lipophilicity.

Accordingly, five different ligands predicated on the (S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT platform were assembled (Schemes 2 and 3): 1) the hexamethylene analogue of 7, (S)-4,5-dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(6-methoxyhexyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic acid [(S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT-HXME, 10]; 2) the corresponding alcohol of 10, (S)-4,5-dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(6-hydroxyhexyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic acid [(S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT-HXA, 11]; 3) the putative first metabolite of 11, (S)-4,5-dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(5-carboxypentyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic acid [(S)-4'-(5-carboxypentyloxy)-DADFT, 12]; 4) the β-oxidation product of 11, (S)-4,5-dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(3-carboxypropyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic acid [(S)-4'-(3-carboxypropyloxy)-DADFT, 13], and 5) the second β-oxidation product of 11, (S)-4,5-dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(carboxymethoxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic acid [(S)-4'-(carboxymethoxy)-DADFT, 14]. The conversion of the parent alcohol 11 to its putative metabolites 12–14 (Figure 6) was assessed in rats given 11 sc at a dose of 300 µmol/kg. In addition, the ligands were evaluated for their log Papp, and their ICE in rats and primates (Table 2).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of (S)-4,5-Dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(6-methoxyhexyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic Acid (10) and (S)-4,5-Dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(6-hydroxyhexyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic Acid (11)a

aReagents and conditions: (a) 25% NaOCH3 (1.0 equiv), DMF, 63 °C, 17 h, 28%; (b) K2CO3 (2.0 equiv), DMF, 62 °C, 22 h, 59%; (22); K2CO3 (1.9 equiv), DMF, 70 °C, 18 h, 53% (24); (c) 50% NaOH (aq), CH3OH, 97% (10) 91% (11).

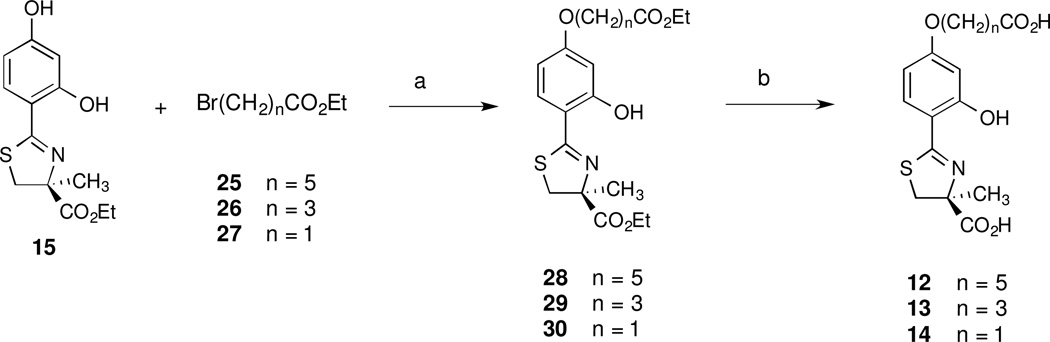

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of (S)-4,5-Dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(5-carboxypentyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic Acid (12), (S)-4,5-Dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(3-carboxypropyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic Acid (13), and (S)-4,5-Dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(carboxymethoxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic Acid (14)a

aReagents and conditions: (a) K2CO3 (1.3 equiv), NaI, DMF, 65 °C, 5 d, 61% (28); K2CO3 (1.3 equiv), NaI, DMF, 100 °C, 2 d, 72% (29); K2CO3 (2.1 equiv), NaI, DMF, 70 °C, 20 h, 66% (30); (b) 50% NaOH (aq), CH3OH, 99% (12), 90% (13), 98% (14).

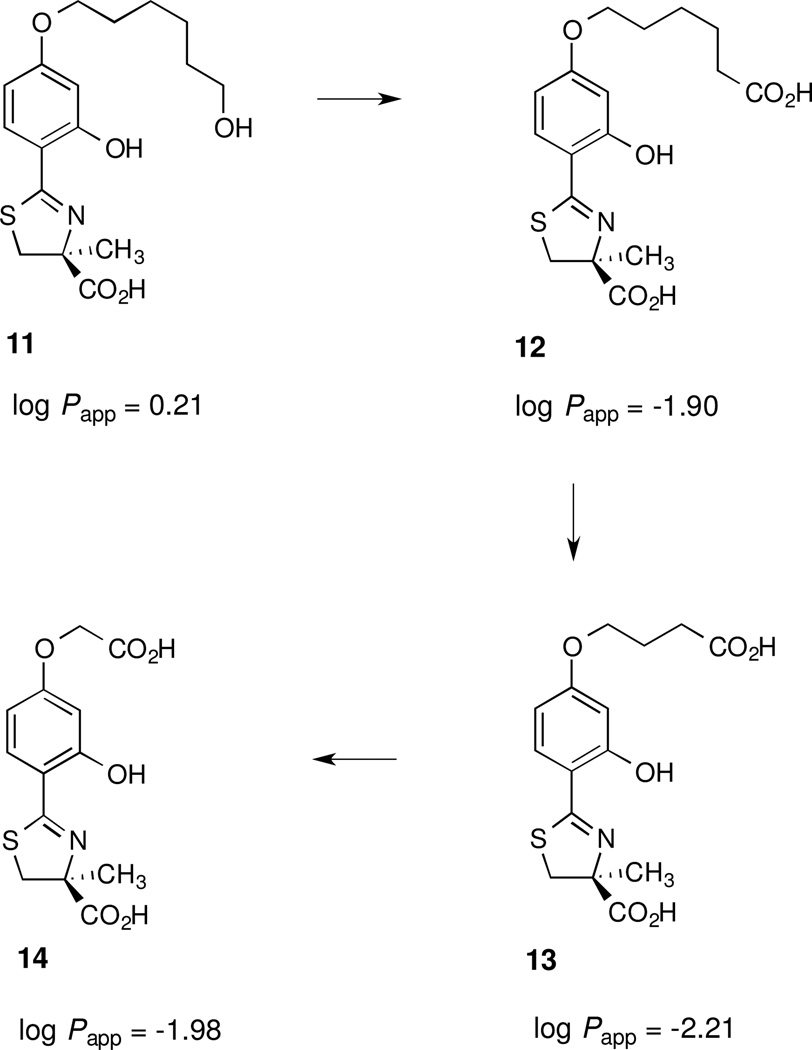

Figure 6.

The structures of the putative metabolites of 11, 12–14, and the lipophilicity (log Papp) of the ligands.

2.7 Synthesis of Deferitrin Hexamethylene Methyl Ether, (S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT-HXME (10), the Corresponding Alcohol Analogue, (S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT-HXA (11), and its Putative Metabolites 12, 13, and 14

Synthesis of the methyl ether-containing chelator 10 required first generating 6-iodo-1-methoxyhexane (21) [74] from 1,6-diiodohexane (20) in 28% yield by employing 25% NaOCH3 (1 equivalent) in DMF at 63 °C (Scheme 2). Alkylation of deferitrin ethyl ester (15) with 21 using K2CO3 in DMF at 62 °C, generated intermediate 22 in 59% yield. Alkaline cleavage of ester 22 provided (S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT-HXME (10) in 97% yield. The synthesis of alcohol 11 involved first alkylating the ester of deferitrin (15) with 6-iodohexyl acetate (23) [75] utilizing K2CO3 in DMF at 70 °C, giving diester 24 in 53% yield (Scheme 2). Alkaline hydrolysis of 24 provided the final product 11 in 91% recrystallized yield.

Synthesis of the anticipated metabolites of alcohol 11 (12–14) followed methodology similar to that of polyether acid 9 (Scheme 3). The DADFT ester 15 was selectively alkylated with one of three ethyl ω-bromoalkanoates (25, 26, or 27) in DMF in the presence of K2CO3 and catalytic iodide salt. The corresponding diesters 28, 29, and 30 were obtained in 61, 72, and 66% yields. Once again, these diesters were cleaved in 50% NaOH in CH3OH, giving the required acids 12, 13, and 14 in 99, 90, and 98% yields, respectively.

2.8 Tissue Distribution/Metabolism of (S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT-HXA (11): A Metabolically Programmed Ligand

In order to verify that conversion of the alcohol 11 to its putative metabolites 12–14 (Figure 6) was occurring in vivo, rats were given the parent alcohol 11 sc at a dose of 300 µmol/kg. The rats were euthanized 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 h post drug. The conversion of 11→ 12–14 was assessed in the animals’ plasma, liver, kidney, heart and pancreas. Significant conversion of 11→ 12–14 was found in all of the tissues examined (Figure 7). The extent and rapidity of metabolism of 11→12–14 that unfolded was surprising. Chelator 11 and its metabolites achieve a concentration of 400 µM in the plasma at 0.5 h post drug. This tissue concentration is very similar to that seen with the 4-norpolyether 7 itself (Figure 5). However, again with 7, the parent represented 95% of the total drug concentration, while its metabolite (8) only accounted for 5% of the total drug. In the case of 11 in the plasma at 0.5 h, only 22% of the total (parent + metabolites) was in the form of the parent 11 (Figure 7). The first β-oxidation product 13 comprised 62% of the total, while the second β-oxidation product 14 represented 16% of the total. The ratio of the parent 11 to its metabolites 13 and 14 was similar at the 1 and 2 h time points. By 4 h post dosing, the parent 11 was no longer detectable, and metabolites 13 and 14 each accounted for 50% of the total. At 8 h post dosing, the total plasma drug concentration had decreased to 23 µM. Metabolite 13 accounted for 65% of this quantity, while the remainder was in the form of metabolite 14. None of the first oxidation product of alcohol 11, the dicarboxylic acid 12, was detected in the plasma.

Figure 7.

Tissue metabolism/distribution of metabolically programmed DADFT analogue 11 in rat plasma, liver, kidney, heart and pancreas. The rats (n=3 per group) were given the drug sc at a dose of 300 µmol/kg. The chelator concentration data (y-axis) are expressed as nmol/g wet weight, or µM (plasma).

Significant conversion of 11→12–14 also occurred in the liver (Figure 7). Interestingly, the parent 11 was not found in the liver at any of the time points. However, unlike the plasma, small quantities of first oxidation product of alcohol 11, the dicarboxylic acid 12, were found in the liver 0.5 and 1 h post drug. At 0.5 h, 12 represented 11% of the total drug (parent + metabolites); the first β-oxidation product 13 comprised 71% of the total, while the second β-oxidation product 14 represented 18% of the total. At 1 h post dosing, the concentration of metabolites 12 and 13 in the liver had decreased to 2% and 73% of the total, respectively, while the proportion of 14 had increased to 25% (Figure 7). Ligand 12 was not detected in the liver 2, 4, or 8 h post dosing. Metabolite 13 accounted for 66% of the total drug (parent + metabolites) at 2 h, and 70% of the total at 4 h. By 8 h post dosing, no 13 remained in the liver, and only trace amounts of 14 were detected.

The parent drug 11 was found in the kidney in trace amounts 0.5 h post drug, and the carboxylic acid 12 was found at 0.5 and 1 h post drug. Metabolite 13, the first β-oxidation product, achieves very high levels in the kidney, ~300 nmol/g wet weight at 0.5 and 1 h, but is not detectable 8 h post dosing. Metabolite 14, the second β-oxidation product, also reached high levels in the kidney at 0.5, 1, and 2 h, 156, 201, and 161 nmol/g wet weight, respectively, but had decreased to only 5 nmol/g wet weight at 8 h.

The parent drug 11 was found in the heart at 0.5 h post drug, 26 nmol/g wet weight. The dicarboxylic acid 12 was not found in the cardiac tissue at any of the time points. The concentration of metabolite 13 in the heart was ~ 46 nmol/g wet weight 0.5 and 1 h post drug, but was not found in the later time points. Metabolite 14 was found in the heart 0.5 and 1 h post dosing, 17 and 23 nmol/g wet weight, respectively, but was not found in the 2–8 h time points (Figure 7).

In the pancreas, the parent 11 was only found 0.5 h post drug, < 5 nmol/g wet weight. Metabolite 12 was not found at any of the time points. Ligand 13 was present in the 0.5 and 1 h samples, 19 and 23 nmol/g wet weight, respectively (Figure 7). Trace amounts of 14 were found at 0.5, 1, and 2 h post dosing. Ligands 11–14 were not detected in the pancreas at 4 or 8 h post drug.

2.9 Chelator-Induced Iron Clearance of 10–14 in Non-Iron-Overloaded, Bile Duct-Cannulated Rodents

Ligands 10–14 were administered to the rats po at a dose of 300 µmol/kg; 12–14 were given to the animals sc at the same dose. The first chelator evaluated in the rats was 10, the non-metabolizable methyl ether analogue of 11. Ligand 10 is very lipophilic (log Papp = 0.95), and is also profoundly toxic. When it was given po to bile duct-cannulated rats, one of animals died ~ 22 h post drug. The remaining rodents were euthanized 24 h post dosing due to their rapidly deteriorating condition. We had seen this same scenario with (S)-2-(4-butoxy-2-hydroxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydro-4-thiazolecarboxylic acid, the 4'-butoxy analogue of 2 (log Papp = 1.02), with deaths occurring within 24 h [76]. Nonetheless, 10 was a very active decorporation agent. The baseline iron output for rats treated with 10 was 5 µg/kg of iron. The drug-induced iron excretion peaked 6 h post drug, 300 µg/kg of iron, and was still 80 µg/kg of iron when the rodents were euthanized 24 h post dosing. The ICE of the drug was 15.8 ± 3.7% (Table 2), and clearly would have been higher had the animals survived. The ICE of 10 was not assessed in the primates due to the overt toxicity seen with the rodents. The ICE and toxicity of 10 is in keeping with the molecule’s lipophilicity. Next, 11, the O-demethylated, metabolically labile analog of 10 was evaluated.

An alkanol, e.g., a 6-(HO) hexyl fragment, was fixed to the 4'-(HO) position of 15 leading to 11 (Scheme 2). This resulted in a less lipophilic, log Papp = 0.21, less toxic ligand than 10. Chelator 11 was given to the rats po at a dose of 300 µmol/kg. The drug was well absorbed, had an ICE of 9.9 ± 0.8%, and did not present with any overt toxicity. As described above, when ligand 11 was given to rats sc, it was quickly converted to the corresponding hydrophilic metabolites, carboxylic acid (12, log Papp = −1.90) [68,70], with β-oxidations [77] to acids 13 log Papp = −2.21 and acid 14 log Papp = −1.98 (Figure 6). The ICEs of 12–14 were determined in rodents given the drugs po and sc at a dose of 300 µmol/kg. The po ICE of the putative first metabolite, 12, was similar to that of 11, 8.8 ± 1.8% (p > 0.05). However, the po ICEs of 13 and 14 were significantly less than 11, 3.7 ± 1.7% (p < 0.001) and 2.6 ± 1.6% (p < 0.005), respectively. When 12 and 13 were given to the rats sc, their ICEs were within error of when the drugs were dosed po (Table 2). In contrast, the ICE of 14 given sc (6.0 ± 1.9%) was more than twice that of when the drug was given po (2.6 ± 1.6%, p < 0.05).

2.10 Chelator-Induced Iron Clearance of 11–14 in Iron-Overloaded Primates

Ligand 11 was administered to the primates po at a dose of 75 µmol/kg; 12–14 were given po and sc at the same dose. Ligand 11, in which a 6-(HO)-hexyl fragment was fixed to the 4'-(HO) position of 2, was very lipophilic (log Papp = 0.21). The ICE of this compound given to the monkeys po was 21.9 ± 3.6% (Table 2). The ICEs of the much more hydrophilic metabolites of 11, 12–14, given po to the monkeys, were all significantly less than the parent. The first oxidation product of alcohol 11, the dicarboxylic acid 12 (log Papp = −1.90), had an ICE of 10.6 ± 4.0% in primates when it was given po (p < 0.01). The first and second β-oxidation products, 13 (log Papp = −2.21) and 14 (log Papp = −1.98), were also significantly less effective than 11 when they were administered po, 5.4 ± 1.5% (p < 0.005) and 3.0 ± 2.7% (p < 0.002), respectively. Again, the reason for the substantial reduction in the efficacy of 12–14 dosed po was likely due to the poor GI absorption of the dicarboxylic acids because of their charge: they are dianions at physiological pH. In order to confirm this, ligands 12–14 were given to the primates sc. In each case, the same animals that had been given the drugs po were also given the chelators sc.

The po ICE of 12 in the monkeys was 10.6 ± 4.0%; the ICE increased to 18.8 ± 8.7% when the ligand was given sc, but the increase was not significant (p = 0.06). The ICE of 13 increased significantly in the primates, from 5.4 ± 1.5% when it was dosed po to 18.1 ± 7.5% when it was administered sc (p < 0.03). Finally, the ICE of the second β-oxidation product 14 in the primates was 3.0 ± 2.7% when it was given po. The ICE increased significantly, to 15.9 ± 4.3%, when it was given to the same animals sc (p < 0.001). Thus, the importance of ligand charge, log Papp, takes on a much more significant role in the primate model.

2.11 ICE Observations

Several generalizations can be derived from Table 2. The performance ratio (PR), ICEprimate /ICErodent, shows that although 8 and 9 (po) were more effective at iron decorporation in the rats than in primates, the remaining ligands 11–14 are either as effective or better at iron clearance in the primates. In the rodents, 9 and 14 were approximately twice as effective sc as when they were dosed po. There was also a dramatic difference in the sc vs po ICEs of 9, 13, and 14 in the primates: their sc ICEs were 10.2, 3.4, and 5.3 times higher, respectively. The ICE of 12 was also increased upon sc dosing, but the increase was not significant (p = 0.06).

2.12 Toxicology Profile of (S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT-HXA (11), A Metabolically Programmed Chelator

The concept behind the development of metabolically programmed iron chelators is predicated on the administration of highly lipophilic drugs that will be well absorbed orally, present with excellent ICE properties, and, to minimize potential toxicity, must be quickly metabolized to less lipophilic but still active deferration agents. For example, deferitrin analog 10 (Table 2), with a non-metabolizable terminal methyl ether, was highly lipophilic and was an effective iron clearing agent in the bile duct-cannulated rats. Unfortunately, the chelator was profoundly toxic. Conversely, the corresponding demethylated compound, alcohol 11, which is also lipophilic, had excellent ICE properties in rodents and primates and did not display any overt toxicity. As described above, ligand 11 was well absorbed, and, in a tissue distribution/metabolism study, was shown to be quickly converted to the corresponding very hydrophilic acids 12, 13, and 14 (Figure 6). However, the real litmus test for the success of the metabolically programmed chelators, e.g., 11, is dependent upon their toxicity profile.

Accordingly, a ten-day toxicity trial of 11 was carried out in male Sprague-Dawley rats. The animals were housed in individual metabolic cages. Ligand 11 was given po by gavage once daily for ten days at a dose of 384 µmol/kg/day. Note that this dose is equivalent to 100 mg/kg/day of DFT (1) as its sodium salt. Urine was collected from the metabolic cages at 24-h intervals and assessed for its Kim-1 content. The studies were performed on rats with normal iron stores; each animal served as its own control. Additional age-matched rats served as untreated controls for the CBC and serum chemistry assessments and histopathology.

All of the rats treated with 11 survived the exposure to the drug. The animals were bright, alert and responsive at the beginning of the study and remained that way throughout the course of the experiment. The rodents’ baseline urinary Kim-1 excretion was < 20 ng/kg/24 h and did not exceed this level at any time during the 10-day exposure to the chelator. The rats were sacrificed 24 h post drug. Blood was submitted for routine CBC and serum chemistry analysis. The BUN of the treated rats, 20 ± 4 mg/dl, was within error of that of the untreated controls, 21 ± 2 mg/dl (p > 0.05). In addition, the SCr for both groups was 0.5 ± 0.1 mg/dl (p > 0.05). Note that these values are well within the normal range for this species: 9–30 mg/dl for BUN, and 0.4–1.0 mg/dl for SCr [78]. Extensive tissues (25/rat) were submitted to an outside lab for assessment of histopathology. The pathologist could not identify any drug-related abnormalities: “There are no definitive differences in the organs of the two groups of rats.”

Taken together, these results unequivocally demonstrate that metabolically programmed ligands that are highly effective deferration agents can be successfully designed. As predicted, the parent in this case, a lipophilic alcohol, 11, was well absorbed and was quickly metabolized to hydrophilic ligands that, collectively, have excellent ICEs with little to no discernable toxicity. Thus, the concept of developing “metabolically programmed” chelators, i.e., highly lipophilic, orally absorbable ligands that are quickly converted to hydrophilic, nontoxic metabolites (e.g., Figure 8), is indeed a credible approach.

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of the oral absorption of the highly lipophilic ligand 11, and its rapid conversion to hydrophilic metabolites 12–14.

3. Conclusion

A number of notable outcomes were derived from the metabolic studies of (S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT-norPE (7). First, ligand 7 does not sustain metabolic cleavage at the 4'-(HO) to yield 2 (Figure 2). However, what remained unclear is whether or not the terminal methyl on the polyether fragment of 7 is metabolically labile. If this were the case, it would likely be converted first to the corresponding alcohol, 8, and then to the carboxylic acid, 9, Figure 4. Both of these metabolic products would be expected to be very hydrophilic. This increase in hydrophilicity, based on previous studies, could further be expected to minimize ligand toxicity [40,46,48]. If indeed such a demethylation-oxidation scenario is occurring with 7, it could support a novel approach to “metabolically programmed” iron chelators, i.e., highly lipophilic chelators that would be absorbed well orally, but would then be quickly metabolized to hydrophilic, nontoxic ligands.

The putative metabolites of 7, 8 and 9, were assembled. The alcohol 8 has a 3-oxa-5-hydroxypentyl fragment fixed to the 4'-(HO); the acid 9 has a 3-oxa-4-carboxybutyl group on the 4'-(HO). These two synthetic chelators allowed us to develop an analytical HPLC method to follow the potential metabolism of 7. When the tissues of rats treated with 7 sc were subjected to further analysis via HPLC for the presence of 8 or 9, cleavage of the terminal methyl of 7 to the corresponding alcohol 8 did occur (Figure 5). However, carboxylic acid 9 was not detected, probably because the extent of the metabolism of the parent 7 to 8 was so minor. In order to verify that conversion of the alcohol 8 to the acid 9 could occur efficiently, rodents were given the synthetic alcohol 8 sc at a dose of 300 µmol/kg. Indeed, alcohol 8 was very quickly oxidized to 9 (Figure 5).

When given po to rodents and primates, neither of the synthetic metabolites of 7, alcohol 8 nor the acid 9, had ICE values as high as the parent ligand. The acid 9, given po, was particularly ineffective. However, when given sc, the ICE of 9 doubled in rodents, and was 10 times higher in primates than when it was given to the same monkeys po (Table 2). This is in keeping with the idea that highly charged ligands do not make it across the intestinal mucosa. Taken collectively, the data suggested that fixing a lipophilic alcohol fragment to the 4'-(HO) of 2 would provide a chelator that should be lipophilic, orally absorbed, and quickly converted to hydrophilic acid metabolites.

Initially a non-metabolizable 6-methoxyhexyl group was appended to the 4'-(HO) of 2, providing methyl ether 10. This ligand was very lipophilic (log Papp = 0.95), had an ICE of 15.8 ± 3.7% in the rats, and was very toxic. We had seen this scenario before with a 4'-butoxy analogue of 2 (log Papp = 1.02), with deaths occurring within 24 h [76]. Nevertheless, this ligand did serve to identify the upper boundary of the lipophilicity/toxicity relationship for this structural family.

Subsequently, a metabolizable 6-hydroxyhexyl group was fixed to the 4'-(HO) of 2, providing alcohol 11 (Table 2). Ligand 11 is still very lipophilic, log Papp = 0.21, but it did not elicit any signs of overt toxicity. As predicted, each of the metabolites of 11 (12, 13, and 14) are very hydrophilic, moving from a log Papp = 0.21 for the parent to −1.90 for acid 12, −2.21 for acid 13, and −1.98 for acid 14 (Figure 6). When given to rats sc, 11 is very quickly converted to the corresponding acid (12), and by β-oxidation to acid 13 and finally to acid 14 (Figure 7).

The po ICE of ligand 11 in the rats is 9.9 ± 0.8%. The po ICE of 12 was similar, while the po ICEs of 13 and 14 were significantly less. In the primates, the po ICE of the parent 11 was 21.9 ± 3.6%. The po ICEs of the hydrophilic metabolites, 12–14, were all significantly less in the monkeys than the parent alcohol 11 (Table 2). Again, this is in keeping with the idea that highly charged ligands do not make it across the intestinal mucosa. To confirm this, ligands 12–14 were given sc to the rodents and primates. In the rats, the sc ICEs of 12 and 13 were within error of their po values, while that of 14 sc was significantly greater than when the drug was given po. In the monkeys, the sc ICE of 12 did increase vs po dosing, but the increase was not significant. In contrast, the sc ICEs of 13 and 14 were 3.4 and 5.3 times greater, respectively, than when the drugs were given to the same animals po (Table 2). The most notable finding was the complete lack of toxicity with ligand 11 when given to rodents once daily for 10 days at a dose of 384 µmol/kg/day. The toxicity difference between 10 and 11 was profound. This substantiates the idea that the lipophilic parent chelator is quickly converted to hydrophilic, nontoxic deferration metabolites. Thus, the concept of developing “metabolically programmed” chelators, i.e., highly lipophilic, orally absorbable and effective molecules that are quickly converted to their hydrophilic counterparts, is indeed a credible approach in the design of highly effective iron chelators. Figure 8 probably best illustrates the concept established in this preliminary study.

4. Experimental Section

4.1 Biology

4.1.1 Materials

Male Cebus apella monkeys were obtained from World Wide Primates (Miami, FL). Male Sprague-Dawley rats were procured from Harlan Sprague-Dawley (Indianapolis, IN). Ultra-pure salts were obtained from Johnson Matthey Electronics (Royston, UK). All hematological and biochemical studies were performed by Antech Diagnostics (Tampa, FL). Histopathological analysis was carried out by Florida Vet Path (Bushnell, FL). Atomic absorption (AA) measurements were made on a Perkin-Elmer model 5100 PC (Norwalk, CT).

4.1.2 Biological Methods

All animal experimental treatment protocols were reviewed and approved by the University of Florida's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

4.1.3 Cannulation of Bile Duct in Non Iron-Overloaded Rats

The cannulation has been described previously [41,43]. Bile samples were collected from male Sprague-Dawley rats (400–450 g) at 3 h intervals for up to 48 h. The urine sample(s) was taken at 24 h intervals. Sample collection and handling are as previously described [41,43].

4.1.4 Iron Loading of Cebus apella Monkeys

The monkeys (3.5–6.5 kg) were iron overloaded with intravenous iron dextran as specified in earlier publications to provide about 500 mg of iron per kg of body weight; the serum transferrin iron saturation rose to between 70 and 80% [41,43]. At least 20 half-lives, 60 days, elapsed before any of the animals were used in experiments evaluating iron-chelating agents.

4.1.5 Primate Fecal and Urine Samples

Fecal and urine samples were collected at 24 h intervals and processed as described previously [41,43,79]. Briefly, the collections began 4 days prior to the administration of the test drug and continued for an additional 5 days after the drug was given. Iron concentrations were determined by flame absorption spectroscopy as presented in other publications [41,43].

4.1.6 Drug Preparation and Administration

In the iron clearing experiments, the rats were given 8–14 orally at a dose of 300 µmol/kg. Ligand 9 and 12–14 were also given sc at the same dose. The primates were given 8–9 and 11–14 orally at a dose of 75 µmol/kg. Ligand 9 and 12–14 were also given sc at the same dose. The chelators were administered as their monosodium salts (prepared by the addition of 1 equiv of NaOH to a suspension of the free acid in distilled water).

4.1.7 Calculation of Chelator Iron Clearing Efficiency (ICE)

The term “ICE” is used as a measure of the amount of iron excretion induced by a chelator. The ICE, expressed as a percent, is calculated as (ligand- induced iron excretion/theoretical iron excretion) × 100. To illustrate, the theoretical iron excretion after administration of 1 mmol of DFO, a hexadentate chelator that forms a 1:1 complex with Fe(III), is 1 milli-g-atom of iron. The theoretical iron outputs of the chelators were generated on the basis of a 2:1 ligand:iron complex. The efficiencies in the rats and monkeys were calculated as set forth elsewhere [40]. Data are presented as the mean ± the standard error of the mean; p-values were generated via a one-tailed Student’s t-test in which the inequality of variances was assumed, and a p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. The p-values for the monkeys that were given 9 and 12–14 po and sc were generated via a one-tailed, paired Student’s t-test; a p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

4.1.8 Collection of Chelator Tissue Distribution Samples from Rodents

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (250–350 g) were given a single sc injection of the monosodium salts of 8 and 11 prepared as described above at a dose of 300 µmol/kg. At times 0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 8 h after dosing (n=3 rats per time point), the animals were euthanized by exposure to CO2 gas. Blood was obtained via cardiac puncture into vacutainers containing sodium citrate. The blood was centrifuged, and the plasma was separated for analysis. The liver, kidney, heart, and pancreas were removed from the animals and frozen.

4.1.9 Tissue Analytical Methods

Tissue samples of animals treated with 8 were prepared for HPLC analysis by homogenizing them in H2O at a ratio of 1:1 (w/v). Then, as a rinse, CH3 OH at a ratio of 1:3 (w/v) was added, and the mixture was stored at −20°C for 30 min. This homogenate was centrifuged. The supernatant was diluted with H2O, vortexed, and filtered with a 0.2 µm membrane. Analytical separation was performed on a Supelco Discovery RP Amide C16 HPLC system with UV detection at 310 nm as described previously [47,80]. Mobile phase and chromatographic conditions were as follows: solvent A, 5% CH3 CN/95% buffer (25 mM KH2 PO4 + 2.5 mM 1-octanesulfonic acid, pH 3.0); solvent B, 60% CH3 CN/40% buffer.

Tissue samples of animals treated with 11 were prepared for HPLC analysis by homogenizing them in 0.5 N HClO4 at a ratio of 1:3 (w/v). Then, as a rinse, CH3 OH at a ratio of 1:3 (w/v) was added, and the mixture was stored at −20°C for 30 min. This homogenate was centrifuged. The supernatant was diluted with 95% buffer (25 mM KH2 PO4, pH 3.0)/5% CH3 CN, vortexed, and filtered with a 0.2 µm membrane. Analytical separation was performed on a Supelco Ascentis Express RP-Amide HPLC system with UV detection at 310 nm as described previously [47,80]. Mobile phase and chromatographic conditions were as for 8.

Ligand concentrations were calculated from the peak area fitted to calibration curves by nonweighted least-squares linear regression with Shimadzu Class-VP 7.4 software. The method had a detection limit of 0.25 µM and was reproducible and linear over a range of 1–1000 µM. Tissue distribution data are presented as the mean; p-values were generated via a one-tailed student’s t-test, in which the inequality of variances was assumed; a p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

4.1.10 Toxicity Assessment of (S)-4'-(HO)-DADFT-HXA (11) in Rats

A 10-day toxicity trial on ligand 11 was performed in rodents. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (n=5, 375–400 g) were given the drug, administered as its monosodium salt, po once daily for 10 days at a dose of 384 µmol/kg/day. Note that this dose is equivalent to 100 mg/kg/day of DFT (1) as its sodium salt. The rats were housed in individual metabolic cages and were weighed each day. A baseline (day 0) urine sample was collected and assessed for its Kim-1 content [48,61]; each animal served as its own control. Chilled urine was collected from the metabolic cages at 24-h intervals as previously described [61] to allow for the determination of Kim-1 levels.

The rats were fasted overnight and were given the chelator first thing in the morning. The rodents were fed •3 h post-drug and had access to food for ~5 h before being fasted overnight. The animals were euthanized one day post drug (day 11). Blood was collected for the performance of a routine CBC and serum chemistries [81]. Extensive tissues [40] were collected and submitted to an outside laboratory for histopathological analysis. Additional age-matched rats served as untreated controls for the CBC and serum chemistries and histopathology. No urine was collected from these animals. The studies were performed on rats with normal iron stores.

4.2. Chemistry

Reagents were purchased from Aldrich Chemical Co. (Milwaukee, WI). Fisher Optima grade solvents were routinely used. DMF was dried over 4 Å molecular sieves. Potassium carbonate was flame activated and cooled in a desiccator over Drierite. Reactions were run under a nitrogen atmosphere, and organic extracts were dried with sodium sulfate and filtered. Silica gel 40–63 from SiliCycle, Inc. (Quebec City, Quebec, Canada) was used for column chromatography. Glassware that was presoaked in 3 N HCl for 15 min, washed with distilled water and distilled EtOH, and oven-dried was used during the isolation of 8–14. Melting points are uncorrected. Optical rotations were run at 589 nm (sodium D line) and 20 °C on a Perkin-Elmer 341 polarimeter, with c being concentration in grams of compound per 100 mL of solution (CHCl3 not indicated). NMR spectra were obtained at 400 MHz (1H) or 100 MHz (13C). Chemical shifts (δ) for 1H spectra are given in parts per million downfield from tetramethylsilane for organic solvents (CDCl3 not indicated) or sodium 3-(trimethylsilyl)propionate-2,2,3,3-d4 for D2O. Chemical shifts (δ) for 13C spectra are given in parts per million referenced to CH3OH (δ 49.50) in D2O or to the residual solvent resonance in CDCl3 (δ 77.16) (not indicated) or DMSO-d6 (δ 39.52). The base peaks are reported for the ESI-FTICR mass spectra. Elemental analyses were performed by Atlantic Microlabs (Norcross, GA) and were within ± 0.4% of the calculated values. The purity of all compounds was confirmed by elemental analysis. Furthermore, the purity of 8–14 was ≥ 95% by HPLC analysis.

4.2.1. (S)-4,5-Dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(5-hydroxy-3-oxapentyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic Acid (8)

A solution of 50% (w/w) NaOH (3.0 mL, 57 mmol) in CH3OH (25 mL) was added slowly to a solution of 17 (2.0 g, 5.4 mmol) in CH3OH (50 mL) at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 16 h, and the bulk of the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in dilute NaCl (50 mL) and was extracted with Et2O (2 × 30 mL). The aqueous layer was cooled in ice, acidified with cold 6 M HCl to pH = 2, and extracted with EtOAc (8 × 30 mL). The combined EtOAc layers were concentrated in vacuo to furnish 1.78 g of 8 (97%) as a yellow oil: [ ] +25.3° (c 0.88). 1H NMR δ 7.9 (br s, 1H), 7.21 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 6.50 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.47 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 4.15–4.19 (m, 2H), 3.74–3.92 (m, 5H), 3.65–3.70 (m, 2H), 3.20 (d, J = 10.8 Hz, 1H), 1.68 (s, 3H). 13C NMR δ 176.29, 171.96, 163.02, 161.32, 131.97, 109.79, 107.69, 101.49, 82.68, 72.57, 69.19, 67.56, 61.78, 39.78, 24.61. HRMS m/z calcd for C15H20NO6S, 342.1006 (M + H), C15H19NNaO6S, 364.0825 (M + Na); found, 342.1014, 364.0826. Anal. Calcd for C15H19NO6S: C, 52.78; H, 5.61; N, 4.10. Found: C, 52.93; H, 5.83; N, 4.02.

4.2.2. (S)-4,5-Dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(4-carboxy-3-oxabutyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic Acid (9)

A solution of 50% (w/w) NaOH (2.88 mL, 55.1 mmol) in CH3OH (30 mL) was added to a mixture of 19 (2.27 g, 5.52 mmol) in CH3OH (62 mL) over 5 min at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 17 h, and the bulk of the solvent was removed by rotary evaporation. The residue was dissolve in 3 M NaCl (70 mL) and was extracted with Et2O (3 × 40 mL). The aqueous layer was cooled in ice, treated with cold 2 M HCl (30 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (100 mL, 4 × 50 mL). Organic layers were combined, washed with 6 M NaCl (80 mL) and concentrated by rotary evaporation. The residue was combined with H2O (43 mL) and 0.1050 M NaOH (52.76 mL, 5.540 mmol), heated on a steam bath and hot suction filtered, washing with H2O (18 mL). The filtrate was diluted with H2O (34 mL) and lyophilized. Solid was dried under high vacuum at 72 °C, furnishing 2.05 g of 9 as its sodium salt (98%) as an amorphous yellow solid: [ ] +124.3° (c 0.73, H2O). 1H NMR (D2O) δ 7.57 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 6.61 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.52 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 4.26–4.30 (m, 2H), 4.06 (s, 2H), 3.90–3.95 (m, 3H), 3.53 (d, J = 11.7 Hz, 1H), 1.74 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (D2O) δ 178.94, 177.92, 177.62, 166.41, 162.21, 134.11, 109.15, 107.12, 102.09, 78.41, 70.23, 69.43, 68.45, 39.67, 23.98. HRMS m/z calcd for C15H15NNaO7S, 376.0472 (M - H), C15H16NO7S, 354.0653 (M - Na); found, 376.0479, 354.0663. A sample (1.00 g) was recrystallized from EtOH (aq) to give 0.631 g of 9 (Na salt). Anal. Calcd for C15H16NNaO7S: C, 47.75; H, 4.27; N, 3.71. Found: C, 47.82; H, 4.43; N, 3.75.

4.2.3. (S)-4,5-Dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(6-methoxyhexyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic Acid (10)

A solution of 50% (w/w) NaOH (1.87 mL, 35.8 mmol) in CH3OH (40 mL) was added over 4 min to a solution of 22 (1.41 g, 3.56 mmol) in CH3OH (80 mL) at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 h, and the bulk of the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was diluted in 2 M NaCl (120 mL) and was extracted with Et2O (3 × 50 mL). The aqueous layer was cooled in ice, acidified with cold 2 M HCl (30 mL), and extracted with EtOAc (100 mL, 3 × 50 mL). The combined EtOAc extracts were washed with 6 M NaCl (60 mL) and concentrated in vacuo to generate 1.275 g of 10 (97%) as a waxy, light tan solid: mp 68–68.5 °C, [ ] +48.8° (c 0.80, DMF). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 13.17 (s, 1H), 12.74 (s, 1H), 7.31 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.52 (dd, J = 8.6, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.50 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 4.00 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 3.79 (d, J = 11.3 Hz, 1H), 3.36 (d, J = 11.3 Hz, 1H), 3.30 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.21 (s, 3H), 1.66–1.74 (m, 2H), 1.58 (s, 3H), 1.47–1.54 (m, 2H), 1.29–1.45 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 173.73, 170.03, 162.96, 160.49, 131.57, 108.97, 107.27, 101.13, 82.45, 71.82, 67.80, 57.79, 28.97, 28.47, 25.42, 25.28, 24.11. HRMS m/z calcd for C18H26NO5S, 368.1526 (M + H); found, 368.1540. Anal. Calcd for C18H25NO5S: C, 58.84; H, 6.86; N, 3.81. Found: C, 58.55; H, 6.81; N, 3.80.

4.2.4. (S)-4,5-Dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(6-hydroxyhexyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic Acid (11)

A solution of 50% (w/w) NaOH (3.12 mL, 59.7 mmol) in CH3OH (95 mL) was added to a mixture of 24 (2.53 g, 5.97 mmol) in CH3OH (100 mL) over 32 min at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 d, and the bulk of the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was treated with 2 M NaCl (150 mL) and was extracted with Et2O (3 × 50 mL). The aqueous layer was cooled in ice, treated with cold 2 M HCl (50 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (2 × 100 mL, 50 mL). Organic layers were combined, washed 6 M NaCl (65 mL) and concentrated by rotary evaporation. The residue was recrystallized from EtOAc/hexanes. Solid was collected and dried under high vacuum at 58 °C, providing 1.917 g of 11 (91%) as pale yellow crystals: mp 116–116.5 °C, [ ] +50.1° (c 0.83, DMF). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 13.20 (s, 1H), 12.73 (s, 1H), 7.32 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 6.52 (dd, J = 8.6, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.50 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 4.35 (br s, 1H), 4.00 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.79 (d, J = 11.3 Hz, 1H), 3.36–3.42 (m, 2H), 3.36 (d, J = 11.3 Hz, 1H), 1.66–1.75 (m, 2H), 1.58 (s, 3H), 1.29–1.48 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 173.76, 170.04, 162.97, 160.50, 131.59, 108.97, 107.28, 101.13, 82.45, 67.85, 60.64, 32.48, 28.56, 25.35, 25.27, 24.12. HRMS m/z calcd for C17H24NO5S, 354.1370 (M + H); found, 354.1384. Anal. Calcd for C17H23NO5S: C, 57.77; H, 6.56; N, 3.96. Found: C, 57.94; H, 6.50; N, 3.93.

4.2.5. (S)-4,5-Dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(5-carboxypentyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic Acid (12)

A solution of 50% (w/w) NaOH (5.00 mL, 95.6 mmol) in CH3OH (50 mL) was added to a mixture of 28 (4.434 g, 10.47 mmol) in CH3OH (120 mL) over 7 min at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 d, and the bulk of the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in 3 M NaCl (110 mL) and was extracted with Et2O (2 × 100 mL). The aqueous layer was cooled in ice, treated with cold 2 M HCl (54 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (150 mL, 2 × 60 mL). Organic layers were combined, washed with 6 M NaCl (100 mL), and concentrated by rotary evaporation. The residue was dried under high vacuum at 57 °C for 16 h to afford 3.80 g of 12 (99%) as light colored crystals: mp 153.5–155 °C, [ ] +47.5° (c 0.76, DMF). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 12.72 (s, 2H), 7.31 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.52 (dd, J = 8.6, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.49 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 4.00 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.79 (d, J = 11.3 Hz, 1H), 3.36 (d, J = 11.3 Hz, 1H), 2.23 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.66–1.75 (m, 2H), 1.58 (s, 3H), 1.51–1.60 (m, 2H), 1.36–1.45 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 174.46, 173.76, 170.05, 162.96, 160.50, 131.60, 108.98, 107.29, 101.16, 82.46, 67.76, 33.61, 28.26, 25.08, 24.25, 24.12. HRMS m/z calcd for C17H22NO6S, 368.1162 (M + H); found, 368.1169. Anal. Calcd for C17H21NO6S: C, 55.57; H, 5.76; N, 3.81. Found: C, 55.58; H, 5.79; N, 3.78.

4.2.6. (S)-4,5-Dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(3-carboxypropyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic Acid (13)

A solution of 50% (w/w) NaOH (6.34 mL, 0.121 mol) in CH3OH (100 mL) was added dropwise to a solution of 29 (6.56 g, 16.6 mmol) in CH3OH (50 mL) at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 36 h, and the bulk of the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in dilute NaCl (150 mL) and was washed with Et2O (2 × 100 mL). The aqueous layer was cooled at 0 °C, acidified with 6 M HCl to pH = 2. Solid was filtered and washed with cold water. Crystallization in hot CH3OH and EtOAc afforded 5.06 g of 13 (90%) as a white solid: mp 202–204 °C, [ ] +22.1° (c 0.086, CH3OH). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 7.32 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.53 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 6.50 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 4.03 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.79 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1H), 3.35 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1H), 2.38 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.93 (quintet, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.57 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 177.42, 177.11, 173.34, 166.13, 163.85, 135.00, 112.48, 110.60, 104.58, 85.86, 70.38, 33.42, 27.51, 27.43. HRMS m/z calcd for C15H18NO6S, 340.0849 (M + H); found, 340.0849. Anal. Calcd for C15H17NO6S: C, 53.09; H, 5.05; N, 4.13. Found: C, 52.81; H, 5.17; N, 4.09.

4.2.7. (S)-4,5-Dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(carboxymethoxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylic Acid (14)

A solution of 50% (w/w) NaOH (5.60 mL, 0.107 mol) in CH3OH (75 mL) was added to a solution of 30 (4.32 g, 11.76 mmol) in CH3OH (120 mL) over 10 min at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 d, and the bulk of the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in H2O (120 mL) and was extracted with Et2O (2 × 100 mL). The aqueous layer was cooled in ice, treated with 2 M HCl (60 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (150 mL, 2 × 100 mL). Organic layers were combined, washed with 6 M NaCl (100 mL), and concentrated by rotary evaporation. The residue was dried under high vacuum to afford 3.589 g of 14 (98%) as a pale yellow solid: mp 206–206.5 °C (dec), [ ] +56.3° (c 0.76, DMF). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 13.14 (s, 2H), 12.75 (s, 1H), 7.34 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.53 (dd, J = 8.6, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.47 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 4.75 (s, 2H), 3.79 (d, J = 11.3 Hz, 1H), 3.37 (d, J = 11.3 Hz, 1H), 1.58 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 173.71, 170.04, 169.72, 161.94, 160.33, 131.62, 109.52, 107.17, 101.46, 82.47, 64.57, 39.34, 24.09. HRMS m/z calcd for C13H14NO6S, 312.0536 (M + H); found, 312.0546. Anal. Calcd for C13H13NO6S: C, 50.16; H, 4.21; N, 4.50. Found: C, 50.06; H, 4.38; N, 4.41.

4.2.8. Ethyl (S)-4,5-Dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(5-hydroxy-3-oxapentyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylate (17)

Potassium carbonate (2.76 g, 20.0 mmol) and KI (200 mg, 1.2 mmol) were added to a mixture of 15 [82] (2.81 g, 10 mmol) in DMF (100 mL). A solution of 16 (1.24 g, 10 mmol) in DMF (10 mL) was added to the reaction mixture, which was heated at 100 °C for 24 h. After cooling to room temperature, H2O (100 mL) was added followed by extraction with EtOAc (2 × 100 mL). Organic layers were combined, washed with H2O (100 mL) and 6 M NaCl (100 mL), and solvent was removed in vacuo. Column chromatography using 30% EtOAc/CH2Cl2 furnished 2.30 g of 17 (62%) as a viscous oil: [ ] +48.0° (c 0.15). 1H NMR δ 12.70 (br s, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 6.50 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.47 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 4.24 (dq, J = 7.6, 1.6 Hz, 2H), 4.15–4.17 (m, 2H), 3.83–3.88 (m, 3H), 3.76–3.79 (m, 2H), 3.66–3.69 (m, 2H), 3.20 (d, J = 10.8 Hz, 1H), 1.66 (s, 3H), 1.3 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR δ 172.96, 170.92, 162.95, 161.32, 131.87, 110.14, 107.39, 101.51, 83.25, 72.73, 69.54, 67.61, 62.05, 61.89, 39.98, 24.61, 14.23. HRMS m/z calcd for C17H24NO6S, 370.1319 (M + H); found, 370.1323. Anal. Calcd for C17H23NO6S: C, 55.27; H, 6.28; N, 3.79. Found: C, 54.99; H, 6.24; N, 3.75.

4.2.9. Ethyl (S)-4,5-Dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-[(4-ethoxycarbonyl)-3-oxabutyloxy]phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylate (19)

Sodium iodide (0.553 g, 3.69 mmol) and K2CO3 (5.13 g, 37.1 mmol) were added to 15 (5.08 g, 18.1 mmol) and 18 [73] (3.31 g, 19.9 mmol) in DMF (46 mL), and the reaction mixture was heated at 95 °C for 22 h. The mixture was cooled, filtered, washing the solids with acetone (100 mL, 2 × 50 mL). Solvents were removed in vacuo, and the concentrate was treated with 1:1 0.5 N HCl/6 M NaCl (120 mL) followed by extraction with EtOAc (100 mL, 2 × 50 mL). Organic layers were combined, washed with 1% NaHSO3 (75 mL), H2O (75 mL) and 6 M NaCl (55 mL), and solvent was removed by rotary evaporation. Flash column chromatography using 8.4:25:66.5 EtOAc/petroleum ether/CH2Cl2 gave 2.574 g of 19 (35%) as a yellow oil: [ ] +41.0° (c 0.68). 1H NMR δ 12.70 (s, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.50 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.47 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 4.17–4.28 (m + s, 8H), 3.92–3.97 (m, 2H), 3.84 (d, J = 11.3 Hz, 1H), 3.20 (d, J = 11.3 Hz, 1H), 1.66 (s, 3H), 1.298 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.290 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR δ 172.96, 170.92, 170.42, 162.88, 161.29, 131.84, 110.13, 107.34, 101.52, 83.25, 69.94, 69.02, 67.71, 62.05, 61.10, 39.97, 24.60, 14.33, 14.22. HRMS m/z calcd for C19H26NO7S, 412.1424 (M + H); found, 412.1440. Anal. Calcd for C19H25NO7S: C, 55.46; H, 6.12; N, 3.40. Found: C, 55.66; H, 6.21; N, 3.44.

4.2.10. 1-Iodo-6-methoxyhexane (21)

Sodium methoxide (25 weight %, 5.5 mL, 24.1 mmol) was added by syringe to 20 (4.0 mL, 24.3 mmol) in DMF (10 mL) over 20 min. The reaction solution was heated at 63 °C for 17 h. After cooling to 0 °C, the reaction solution was treated with 3:1 cold 0.5 M HCl/6 M NaCl (200 mL) and was extracted with EtOAc (2 × 150 mL, 50 mL). The organic extracts were washed with 1% NaHSO3 (150 mL), H2O (2 × 150 mL) and 6 M NaCl (100 mL), and solvent was removed by rotary evaporation. Flash column chromatography using 4% then 6% EtOAc/petroleum ether furnished 1.61 g of 21 [74] (28%) as a liquid: 1H NMR δ 3.37 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.33 (s, 3H), 3.19 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 1.83 (quintet, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 1.54–1.62 (m, 2H), 1.33–1.46 (m, 4H). 13C NMR δ 72.78, 58.72, 33.58, 30.46, 29.57, 25.26, 7.25. HRMS m/z calcd for C7H19INO, 260.0506 (M + NH4); found, 260.0515. Anal. Calcd for C7H15IO: C, 34.73; H, 6.25. Found: C, 34.44; H, 6.19.

4.2.11. Ethyl (S)-4,5-Dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(6-methoxyhexyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylate (22)

Potassium carbonate (1.81 g, 13.1 mmol) was added to 15 (1.77 g, 6.29 mmol) and 21 (1.56 g, 6.44 mmol) in DMF (32 mL), and the reaction mixture was heated at 62 °C for 22 h. After cooling in an ice bath, cold 0.5 M HCl (100 mL) was added followed by extraction with EtOAc (120 mL, 2 × 50 mL). Organic layers were combined and washed with 1% NaHSO3 (100 mL), H2O (3 × 100 mL) and 6 M NaCl (80 mL), and solvent was removed by rotary evaporation. Flash column chromatography using 10% EtOAc/petroleum ether then 1:3:6 EtOAc/petroleum ether/CH2Cl2 gave 1.47 g of 22 (59%) as a viscous yellow oil: [ ] +43.3° (c 0.72). 1H NMR δ 12.68 (s, 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.47 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.43 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 4.18–4.29 (m, 2H), 3.97 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 3.83 (d, J = 11.3 Hz, 1H), 3.38 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.34 (s, 3H), 3.19 (d, J = 11.3 Hz, 1H), 1.75–1.83 (m, 2H), 1.65 (s, 3H), 1.56–1.64 (m, 2H), 1.37–1.53 (m, 4H), 1.30 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR δ 173.02, 170.92, 163.50, 161.34, 131.77, 109.71, 107.40, 101.36, 83.23, 72.86, 68.19, 62.02, 58.70, 39.96, 29.69, 29.14, 26.03, 25.99, 24.61, 14.22. HRMS m/z calcd for C20H30NO5S, 396.1839 (M + H); found, 396.1858. Anal. Calcd for C20H29NO5S: C, 60.74; H, 7.39; N, 3.54. Found: C, 60.59; H, 7.29; N, 3.60.

4.2.12. Ethyl (S)-4,5-Dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(6-acetoxyhexyloxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylate (24)

Potassium carbonate (3.42 g, 24.8 mmol) was added to 15 (3.255 g, 11.57 mmol) and 23 [75] (3.44 g, 12.7 mmol) in DMF (60 mL), and the mixture was heated at 70 °C for 21 h. After cooling to 0 °C, cold 0.5 M HCl (150 mL) was added followed by extraction with EtOAc (150 mL, 2 × 80 mL). Organic layers were combined, washed with 1% NaHSO3 (150 mL), H2O (3 × 150 mL) and 6 M NaCl (100 mL), and solvent was removed by rotary evaporation. Flash column chromatography using 1:3:6 EtOAc/petroleum ether/CH2Cl2 gave 2.60 g of 24 (53%) as a white solid: mp 58.5–60 °C, [ ] +40.1° (c 0.98). 1H NMR δ 12.69 (s, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 6.47 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.43 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 4.20–4.28 (m, 2H), 4.07 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 3.97 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.84 (d, J = 11.3 Hz, 1H), 3.19 (d, J = 11.3 Hz, 1H), 2.05 (s, 3H), 1.76–1.84 (m, 2H), 1.62–1.70 (m, 2H), 1.66 (s, 3H), 1.38–1.54 (m, 4H), 1.30 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR δ 173.01, 171.39, 170.93, 163.45, 161.36, 131.79, 109.76, 107.40, 101.35, 83.23, 68.10, 64.58, 62.03, 39.98, 29.07, 28.66, 25.84, 25.83, 24.62, 21.16, 14.23. HRMS m/z calcd for C21H30NO6S, 424.1788 (M + H); found, 424.1798. Anal. Calcd for C21H29NO6S: C, 59.56; H, 6.90; N, 3.31. Found: C, 59.71; H, 6.81; N, 3.33.

4.2.13. Ethyl (S)-4,5-Dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-[5-(ethoxycarbonyl)pentyloxy]phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylate (28)

Potassium carbonate (3.19 g, 23.1 mmol), NaI (0.351 g, 2.34 mmol), and a solution of 25 (4.46 g, 20.0 mmol) in DMF (25 mL) were added to a solution of 15 (5.0 g, 17.8 mmol) in DMF (100 mL). The reaction mixture was heated at 65 °C for 5 d. After cooling to room temperature, the solvent was removed by rotary evaporation. The residue was treated with cold 0.5 M HCl (200 mL) and was extracted with EtOAc (150 mL, 2 × 50 mL). The organic extracts were washed with 1% NaHSO3 (100 mL), H2O (100 mL), 6 M NaCl (50 mL), and solvent was removed in vacuo. Column chromatography using 30% EtOAc/petroleum ether furnished 4.586 g of 28 (61%) as an off-white solid: mp 61–62 °C, [ ] +40.94° (c 0.171). 1H NMR δ 12.68 (s, 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.47 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.42 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 4.24 (dq, J = 7.2, 2.0 Hz, 2H), 4.13 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.97 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.84 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1H), 3.19 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1H), 2.33 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.77–1.84 (m, 2H), 1.67–1.73 (m, 2H), 1.66 (s, 3H), 1.46–1.54 (m, 2H), 1.30 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.26 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR δ 173.70, 172.96, 170.88, 163.38, 161.31, 131.75, 109.73, 107.32, 101.33, 83.20, 67.93, 61.99, 60.37, 39.93, 34.31, 28.85, 25.68, 24.78, 24.58, 14.36, 14.20. HRMS m/z calcd for C21H30NO6S, 424.1788 (M + H); found, 424.1784. Anal. Calcd for C21H29NO6S: C, 59.56; H, 6.90; N, 3.31. Found: C, 59.69; H, 6.78; N, 3.24.

4.2.14. Ethyl (S)-4,5-Dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-[3-(ethoxycarbonyl)propyloxy]phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylate (29)

Potassium carbonate (4.41 g, 32.0 mmol) and NaI (182 mg, 1.2 mmol) were added to a mixture of 15 (6.90 g, 24.5 mmol) and 26 (5.27 g, 27.0 mmol) in DMF (150 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 6 h and then heated at 100 °C for 48 h. After cooling to room temperature, the solvent was removed by rotary evaporation under high vacuum, and the residue was treated with 0.2 M HCl/6 M NaCl (50 mL) followed by extraction with EtOAc (4 × 30 mL). The organic extracts were washed with 1% NaHSO3 (150 ml), H2O (150 mL) and 6 M NaCl (150 mL), and solvent was removed in vacuo. Column chromatography using 30% EtOAc/CH2Cl2 gave 6.94 g of 29 (72%) as a light yellow viscous oil: [ ] +44.35° (c 0.372). 1H NMR δ 12.65 (s, 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.47 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.42 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 4.24 (dq, J = 7.2, 1.6 Hz, 2H), 4.15 (q, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 4.03 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.84 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1H), 3.19 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1H), 2.51 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 2.11 (quintet, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 1.66 (s, 3H), 1.30 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 3H), 1.26 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR δ 173.21, 172.98, 170.90, 163.15, 161.32, 131.81, 109.91, 107.24, 101.44, 83.23, 67.02, 62.02, 60.63, 39.96, 30.84, 24.60, 24.55, 14.35, 14.22. HRMS m/z calcd for C19H26NO6S, 396.1475 (M + H); found, 396.1475. Anal. Calcd for C19H25NO6S: C, 57.71; H, 6.37; N, 3.54. Found: C, 57.72; H, 6.23; N, 3.52.

4.2.15. Ethyl (S)-4,5-Dihydro-2-[2-hydroxy-4-(ethoxycarbonylmethoxy)phenyl]-4-methyl-4-thiazolecarboxylate (30)