Abstract

Background

Emerging research suggests that some bariatric surgery patients are at a heightened risk for developing substance use problems, especially alcohol use problems.

Methods

An exhaustive literature review was conducted in January 2015 to investigate all articles published that included data on post-operative alcohol use, alcohol use disorders, and illicit drug use among bariatric surgery patients.

Results

Twenty-three studies reported on alcohol and/or substance use among bariatric patients. Six studies longitudinally assessed alcohol use behaviors; three of these studies found an increase in alcohol use following surgery. Six studies were cross-sectional, and two studies assessed medical records. Five studies investigated the prevalence of admissions to substance abuse treatment, and three studies combined alcohol and drug use data in a single index. Six studies reported on illicit drug use and reported low-post-operative use. The studies' samples were primarily non-Hispanic white females in their upper 40s, and only 11 of the 23 studies utilized validated assessment instruments.

Conclusions

Studies employing longitudinal designs and large sample sizes indicate that bariatric patients who had the gastric bypass procedure are at an elevated risk for alcohol use problems post-operatively. Research also indicates that bariatric surgery patients might be over-represented in substance abuse treatment facilities. Risk factors for problematic post-operative alcohol use include regular or problematic alcohol use pre-surgery, male gender, younger age, tobacco use, and symptoms of attention deficient and hyperactivity disorder. As a whole, however, studies indicate bariatric surgery patients demonstrate a low prevalence of problematic alcohol use, and studies about gastric bypass patients are not entirely conclusive. Prospective, longitudinal studies are needed, utilizing standardized and validated alcohol assessment instruments that follow post-operative bariatric patients well beyond 2 years, and account for types of bariatric procedure. Finally, study samples with greater racial/ethnic diversity and wider age ranges are needed.

Keywords: Bariatric surgery, alcohol, substance use, drug use, addiction

Background

The high prevalence of obesity and severe obesity poses both public health and clinical challenges in the United States (Flegal et al., 2012). As a result of this epidemic, a burgeoning number of patients are undergoing bariatric, or weight loss (WLS), surgery (Buchwald et al., 2004; Nguyen et al., 2011). Despite the potential health benefits of WLS, including the reversal of type 2 diabetes and other cardiometabolic disease risk factors (Abbatini et al., 2013; Buchwald et al., 2004; De La Cruz-Munoz, et al., 2013; Heneghan, et al., 2013) reports of post-surgical substance use problems, and alcohol use problems in particular (Conason, et al., 2012; King et al., 2012; Svennson et al., 2013) have recently emerged.

Current alcohol or illicit drug use disorder is among the exclusion criterion for undergoing WLS in the United States (Mechanick et al., 2013). Furthermore, many WLS facilities recommend that all patients avoid alcohol for several months after surgery to promote post-surgical healing and prevent macronutrient deficiencies (Mechanick et al., 2013). Recent studies suggest that certain subsets of WLS patients may be vulnerable to developing post-surgical substance use disorders, specifically alcohol use disorders (AUD; King et al., 2012, Suzuki et al., 2012; Svensson et al., 2013).

The two most common types of WLS procedures in the United States are the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and the laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB) procedure. The RYGB procedure involves the creation of a small stomach pouch and re-routing of the digestive tract with food bypassing most of the stomach and part of the small intestine, resulting in the malabsorption and restriction of calories. The adjustable band procedure (AGB) on the other hand, is much less invasive, and involves an adjustable band placed around the upper stomach, restricting the amount of food the patient can consume (de la Cruz-Muñoz et al., 2011).

Psychological and physiological factors have been suggested to explain the heightened vulnerability for post-operative problematic alcohol use. The nervous system has a remarkably similar response to the consumption of (1) drugs of abuse and (2) overeating (Kenny, 2011 Volkow et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2003). As such, an “addiction transfer” model has been suggested, meaning that one may trade an “addiction” for food to an “addiction” to drugs or alcohol post-surgery (McFadden, 2010). Second, as will be discussed further, certain WLS procedures (i.e. the RYGB procedure) can cause a heightened sensitivity to alcohol post-operatively (Hagerdorn, Encarnacion, Brat, & Morton, 2007; Klockhoff, Näslund, & Jones, 2002; Woodard, Downey, Hernandez-Boussard, & Morton, 2011).

To date, there has not been a review of the literature to assess: (a) types and rates of alcohol and illicit drug use in post-WLS populations; (b) correlates of post-surgical alcohol and illicit drug use disorders; and (c) implications for future research. The current paper is the first systematic, comprehensive, and critical review of the literature; we examine published articles reporting on alcohol use, problematic alcohol use, and illicit drug use among post-operative WLS patients, and provide recommendations for future research.

Method

A systematic review of the literature was conducted in January 2015 using the following electronic databases: Medline, Psych INFO, and Social Work Abstracts. Keyword searches were conducted using Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” to specify or broaden the search. The term “bariatric surgery,” was included with all keywords. Separate searches were conducted using specific keywords including: “alcohol*,” “psychosocial,” and “substance,” The wildcard character “*” was used to truncate words to include all forms of the root word.

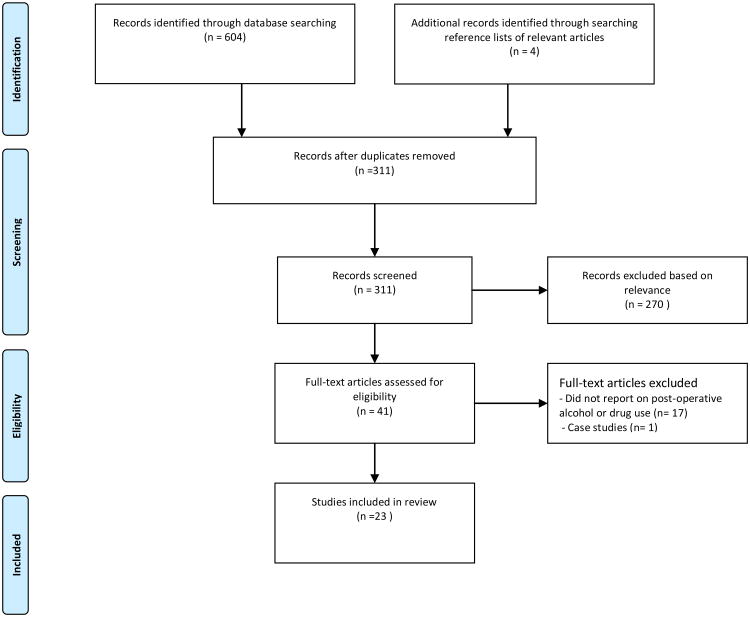

Articles were included in the review if they were published in a peer-reviewed journal (online and/or print format) and addressed: (a) alcohol use and/or (b) illicit drug use among people who had WLS. There was no restriction on publication date or language. Case studies were not included in the review as they are not generalizable to a broader population. Data were abstracted independently by two of the authors to ensure reliability. Figure 1 details the study selection process.

Figure 1.

Review

A total of 23 studies met the search criteria. Nineteen studies reported on alcohol use, and six on illicit drug use (five of these studies also reported on alcohol use). Three studies combined alcohol and drug use into one variable. Overall, study samples were comprised of mainly non-Hispanic white females with mean ages ranging from 40 to 57. Data, including sample demographics and findings regarding alcohol and illicit drug use, were extracted (see Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1. Characteristics of published studies examining alcohol and illicit drug use in post-bariatric populations.

| Study | Research Design

|

Sample

|

Methods

|

Substance Use Outcomes Measured |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Svensson et al., 2013 |

|

|

|

|

| King et al., 2012 |

|

|

|

|

| Conason et al., 2012 |

|

|

|

|

| Wee et al., 2014 |

|

|

|

|

| Lent et al., 2013 |

|

|

|

|

| Alfonsson et al., 2014 |

|

|

|

|

| Buffington, 2007 |

|

|

|

|

| Ertelt et al., 2008 |

|

|

|

|

| Mitchell et al., 2001 |

|

|

|

|

| Macias & Leal, 2003 |

|

|

|

|

| Suzuki et al., 2012 |

|

|

|

|

| Odom et al., 2010 |

|

|

|

|

| Adams et al., 2012 |

|

|

|

|

| Tedesco et al., 2013 |

|

|

|

|

| Saules et al., 2010 |

|

|

|

|

| Wiedemann et al., 2013 |

|

|

|

|

| Cuellar-Barboza et al., 2014 |

|

|

|

|

| Ostlund et al., 2013 |

|

|

|

|

| Omalu et al., 2007 |

|

|

|

|

| Reslan, Saules, Greenwald, & Schuh, 2014 |

|

|

|

|

| Ivezaj, Saules, & Schuh, 2014 |

|

|

|

|

| Fowler et al., 2014 |

|

|

|

|

| Fogger et al., 2012 |

|

|

|

|

Key: N.D. = no data; N/A= not applicable; RYGB = Roux en y gastric bypass; ASG = sleeve gastrectomy; AGB= Adjustable Gastric Band; VBG = vertical banded gastroplasty (stomach stapling); SD=standard deviation

Table 2. Summary of results among studies examining alcohol and illicit drug use in post-bariatric populations.

| Outcome Measured | Reference | Results |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

Post-surgical problematic alcohol use/alcohol use disorders (AUDs)

|

Svensson et al., 2013 |

|

| King et al., 2012 |

|

|

| Wee et al., 2014 |

|

|

| Alfonsson et al., 2014 |

|

|

| Suzuki et al., 2012 |

|

|

| Ertelt et al., 2008 |

|

|

| Buffington, 2007 |

|

|

| Saules et al., 2010 |

|

|

| Wiedemann et al., 2013 |

|

|

| Cuellar-Barboza, et al., 2014 |

|

|

| Ostlund et al., 2013 |

|

|

| Adams et al., 2012 |

|

|

| Mitchell et al., 2001 |

|

|

| Macias & Leal, 2003 |

|

|

| Odom et al., 2010 |

|

|

| Tedesco et al., 2013 |

|

|

| Fogger et al., 2012 |

|

|

|

| ||

Post-surgical alcohol use/frequency of alcohol use

|

Conason et al., 2012 |

|

| Lent et al., 2013 |

|

|

| Odom et al., 2010 |

|

|

|

| ||

Post-surgical change in sensitivity to alcohol (subjective account)

|

Ertelt et al., 2008 |

|

| Buffington, 2007 |

|

|

|

| ||

| Post-surgical illicit drug use | Conason et al., 2012 |

|

| Mitchell et al., 2001 |

|

|

| Suzuki et al., 2012 |

|

|

| Adams et al., 2012 |

|

|

| Tedesco et al., 2013 |

|

|

| Omalu et al., 2007 |

|

|

|

| ||

Post-surgical “substance” abuse (combined alcohol and illicit drug use)

|

Reslan et al., 2014 |

|

| Ivezaj et al., 2014 |

|

|

| Fowler et al., 2014 |

|

|

Key: N.D. = no data; RYGB = Roux en y gastric bypass; ASG = sleeve gastrectomy; AGB= Adjustable Gastric Band; VBG = vertical banded gastroplasty (stomach stapling);

Alcohol

Nineteen studies reported on alcohol use in post-operative WLS patients (Table 1 and 2). Six of these studies used a longitudinal design and assessed patient alcohol use both pre- and post-operatively. Six studies were cross-sectional; pre-surgical alcohol use data (if applicable) was determined through retrospective report or medical charts. Two studies reviewed medical records for alcohol use data. Finally, five studies investigated the prevalence of WLS patients admitted to in-patient treatment for problematic alcohol use.

Longitudinal Studies

Svensson and colleagues (2013) and King and colleagues (2012) conducted the two most rigorous studies to date, using large sample sizes and prospective, longitudinal designs. Svensson and colleagues (2013) conducted the largest investigation of alcohol use among WLS patients and utilized a non-surgical control group. The authors examined long-term changes in alcohol use risk behaviors and alcohol use disorders at baseline, six months and then 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 15, and 20 years post-WLS, among Swedish women (2,010 WLS patients and 2,037 non-surgical control patients; see Table 1). Overall, the vast majority of respondents (93.1% of the WLS group and 96% of the non-surgical group) demonstrated a low prevalence of problematic alcohol use behaviors at all assessment time points.

However, compared to the non-surgical control group, patients who underwent the RYGB procedure were nearly three times as likely to report alcohol use at the medium risk level (defined by the World Health Organization as over 1.5 drinks per day for women), almost five times more likely to have an alcohol abuse diagnosis (as obtained from medical records), and almost six times more likely to report “problems with alcohol” (Table 2; Svensson et al., 2013). Patients who underwent the less-invasive AGB procedure did not demonstrate higher alcohol risk behaviors when compared to the control group. Data concerning alcohol use frequency was collected using a dietary questionnaire. Data concerning problems with alcohol was determined from the question “Do you think you have alcohol problems?” The prevalence of alcohol abuse diagnoses were obtained from medical records (Table 1).

King and colleagues (2012) investigated alcohol use frequency and AUDs at one and two years post-WLS among 1,945 WLS patients; this is the largest investigation of AUDs among WLS patients conducted in the United States. Self-report data collected with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), an empirically validated and widely used assessment (Allen et al., 1997), revealed no increase in alcohol use frequency or AUD symptoms within one post-surgical year (Table 2). However, there was a significant increase in AUDs in the second post-surgical year from 7.6% to 9.6% [p ≤ 0.01])(King et al., 2012). Equally important, RYGB patients were most at risk for AUDs two years post-WLS compared to respondents who underwent the AGB or other surgical procedures (Table 2). Participants were predominantly non-Hispanic white females with a median age of 47.

Conason and colleagues (2012) collected alcohol use frequency data among 155 patients using a questionnaire developed by the study authors (Table 1). While the study had a high attrition rate (i.e., 75% loss to follow up by 24 months) which may have led to biased findings due to differential dropout, RYGB patients demonstrated a significant increase in alcohol use from pre-WLS to 24 months post-WLS (p = 0.011). When examining both RYGB and AGB patients, no significant increase in the frequency of alcohol use was found from pre-WLS to 24 months post-WLS; however, significant increases in alcohol use were found from one month post-WLS to 24 months post-WLS (p < 0.001; Conason et al., 2012). Thus, these data could potentially account for patients adhering to instructions to avoid alcohol use for several months following WLS, suggesting increased alcohol use over time.

Conversely, other studies have reported post-surgical decreases in high-risk alcohol use and overall alcohol consumption, (Table 2; Wee et al., 2014; Lent et al., 2013). Specifically, Wee and colleagues (2014) collected alcohol use data for 541 WLS patients using a shorter, modified version of the AUDIT (AUDIT-C; Dawson et al., 2005; Reinert & Allen, 2007) (Table 1). Half of RYGB patients and 57% of AGB patients who reported high-risk alcohol use at baseline no longer reported high-risk alcohol use at one and two years post-WLS (Table 2). However, it is also important to note that a subset of respondents who did not report high-risk alcohol use before surgery did report high-risk alcohol use at follow-up, representing “new” post-surgical cases of high-risk alcohol use. This sample was predominantly female (76%) and non-Hispanic white (69%) with a mean age of 44 (Wee et al., 2014).

Similarly, Lent and colleagues (2013) prospectively examined alcohol use frequency among 155 RYGB patients and found a significant decrease in frequency of alcohol use post-surgery; 72.3% (n=112) of participants endorsed any alcohol use during the year prior to surgery, which shrank to 63.2% post-surgery (p=.026). Alcohol use data were collected using a non-validated, mailed questionnaire developed by the study authors that was not anonymous. Alcohol use questions are detailed in Table 1, and included: “how often did you have a drink containing alcohol in the past year?” While this study presents important findings regarding a reduction in alcohol use frequency after WLS, due to a lack of methodological rigor (i.e. use of non-validated, identifiable, mailed assessments), and the fact that problematic alcohol use was not assessed, implications are limited. The sample was a mean age of 50.1 years (SD=11.3), and primarily white (98.1%), and female (80.6%).

Alfonsson and colleagues (2014) examined pre- and post-operative problematic alcohol use (as determined by an AUDIT score >8 for men and >6 for women) among 129 Swedish RYGB patients (Table 1). Compared to pre-WLS, post-operative patients had a lower prevalence of alcohol problems (14% vs. 5.4%)(Table 2). Interestingly, however, after surgery three patients met criteria for “alcohol disturbance” (as determined by an AUDIT score over 16), representing new-onset cases. Symptoms of adult ADHD were a risk factor for post-surgical problematic alcohol use. Respondents were an average of 43 years old and 78% female.

Cross-Sectional Studies

Six cross-sectional studies assessed problematic alcohol use, alcohol use disorders, alcohol sensitivity and/or alcohol use frequency in post-operative WLS patients (Table 1). Overall, while the studies report a low prevalence of problematic alcohol use post-surgery, patients with a history of pre-operative AUDs and those who undergo the RYGB bariatric procedure might be at risk for problematic alcohol use post-WLS. However, many of the cross-sectional studies relied on retrospective report of pre-surgical alcohol use and failed to use validated alcohol use assessment instruments; thus findings must be interpreted within these limitations.

Buffington (2007) conducted an online survey of 318 post-WLS patients (predominantly RYGB) using non-standardized assessments; nearly 30% reported difficulty controlling their alcohol intake post-surgery compared to only 4.5% who (retrospectively) reported difficulty pre-surgery (Table 2). Furthermore, 84% of respondents who drank one or more alcoholic beverages weekly indicated that they were more sensitive to alcohol after surgery than before surgery. Nearly half of the sample was between the ages of 36 and 50, and sample was mostly female (93.7%). Race/ethnicity was not reported, but the sample included respondents of various nationalities.

Ertelt and colleagues (2008) investigated alcohol abuse and dependence diagnoses among 70 RYGB patients via a mailed, non-standardized survey based on DSM-IV-TR criteria (Table 1). Prior to surgery, 6 patients (8.6%) retrospectively met criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence. Post-surgery, the prevalence rate was the same, however 2 patients (2.9%) newly met the alcohol use disorders criteria post-surgery (Table 2). Moreover, 54.3% of patients reported responding differently to alcohol post-operatively; 34.3% (n=24) reported quicker intoxication and 20% (n=13) reported feeling intoxicated after drinking lower quantities of alcohol. The sample predominantly consisted of non-Hispanic white females and had a mean age of 49 (SD=9.2) (Table 1).

Mitchell and colleagues (2001) examined AUDs among a sample of 78 RYGB patients via a telephone interview using sections of the SCID (Table 1). Overall, only six patients (7.7%) met criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence post-surgery, which was assessed 13-15 years after surgery (Mitchell et al., 2001). This sample was predominantly female (83%), with a mean age of 57 (range 31-77; SD not reported). Race/ethnicity data were not reported.

Macias and Leal (2003) interviewed 140 WLS patients (post-WLS) and analyzed psychosocial differences among patients meeting DSM-IV criteria for Binge Eating Disorder (BED) prior to surgery. The pre-operative BED group (n=25) was more likely to have symptoms of alcohol dependence post-operatively, based on the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory-II (39.28, SD=22.7 vs. 12.46, SD=18.71; p=.001; Table 2). The sample was primarily female, with the BED group mean age 36.46 (SD=11.72), and non BED group 44.61 (SD=9.92). Race/ethnicity data was not reported, but the study was conducted in Spain.

In a sample of 51 WLS patients, Suzuki and colleagues (2012) collected pre-operative data via medical chart reviews of psychiatric assessments, and post-operative data through telephone interviews using the SCID (Table 1). Thirty-five percent had a history of a lifetime, pre-surgical AUD, and 12% met criteria for current AUD post-WLS. No patients met criteria for an AUD at time of surgery. Post-surgical AUDs were associated with the RYGB procedure (compared to other surgical procedures) and having a lifetime history of a pre-surgical AUD (Table 2). This sample was predominantly female (86.3%) with a mean age of 51 (SD=8.7). Race/ethnicity data were not reported.

Finally, Odom and colleagues (2010) investigated alcohol use frequency and “concern” with alcohol use through mailed, non-standardized surveys to 203 RYGB patients who had WLS over one year ago. Nearly 42% reported never using alcohol before or after WLS, 20.1% identified a decrease in post-surgical alcohol use, and 9.1% reported increased alcohol use post-WLS. Approximately 10% of respondents reported that someone expressed concern about their alcohol or drug use post-operatively, suggesting problematic alcohol use. Of note, only 24.8% of the surveys were returned, making the representativeness of the study questionable. In addition, it is not completely clear if the respondents who reported never using alcohol were referring to lifetime use as the response choice was simply “I never drank alcohol before or after [surgery]” (Odom et al., 2010). The sample was mainly non-Hispanic white (71.9%) and female (85%), with a mean age of 50.6 (SD=9.8).

Medical Record Reviews

Through a review of medical records two studies investigated AUDs among military veterans who had WLS; both studies found a low prevalence of post-operative AUDs. Adams and colleagues (2012) conducted a chart review of 61 predominantly AGB patients (Table 1) and found that 5 patients (8.2%) had a pre-surgical history of alcohol abuse. No patients demonstrated post-surgical AUDs as determined by the AUDIT-C. Tedesco and colleagues (2013) revealed a high prevalence of a pre-surgical DSM-IV-TR-defined alcohol abuse (21.5%) among a sample of 205 veterans. More than half of this sample was RYGB patients. Six patients demonstrated problematic alcohol use at their follow-up assessment. While patients with a history of alcohol abuse seemed more likely to develop an AUD post-surgery, this did not reach statistical significance. Males in their upper 40s to lower 50s were predominantly represented in both studies. Adams et al. (2012) reported a 70% non-Hispanic white sample, and Tedesco and colleagues (2013) did not report race/ethnicity data.

The Prevalence of Bariatric Surgery among Patients in Substance Abuse Treatment

Five studies examined medical records of patients in substance abuse treatment facilities to determine the prevalence of WLS. Because all of these studies reported on treatment admissions for problematic alcohol use, they are reported here. Saules and colleagues (2010) reviewed 7,199 electronic medical records (EMRs) and hard copies of medical charts from admissions to a substance abuse treatment facility in Michigan over the course of 3 years. Based on EMR data, 2% were WLS patients; based on hand searching medical charts, 6% were WLS patients. Well over half (62.3%) of the WLS patients were seeking treatment for alcohol use, and 9.4% were seeking treatment for alcohol as well as an illicit drug. Findings revealed that 43.4% of patients did not engage in heavy alcohol or illicit drug use until after surgery, representing new onset cases. Admission to substance abuse treatment occurred an average of 5.4 (S.D.=3.2) years post-surgery.

Wiedemann and colleagues (2013) conducted a follow up to Saules et al. (2010), and reviewed EMRs of inpatient substance abuse admissions from July 2009 to April 2011 (Table 1). Nearly 3% of 4,658 patients were determined to be WLS patients; the WLS subset was older and more likely to be female and have an alcohol (vs. drug) diagnosis (Table 2). Of this sample, 56 patients participated in a qualitative interview, and the majority of the qualitative interview participants (60%) developed a “new onset” AUD/SUD post-surgery (Wiedemann et al., 2013; Table 2). Respondents who participated in the qualitative interview portion of the study were on average 44.8 years old, primarily non-Hispanic white, and predominantly female (Table 2).

Cuellar-Barboza and colleagues (2014) reported that 4.9% (n=41) of 823 patients in a treatment program for alcohol use problems had undergone the RYGB WLS procedure. Self-reported alcohol consumption patterns as well as clinical impressions and diagnoses, based on DSM-5 criteria, were extracted from EMRs. Nearly 40% (n=16) of the 41 RYGB patients also met criteria for an AUD prior to WLS, and 17% (n=7) did not consume any alcohol prior to WLS. Study authors were contacted to elucidate about the remaining 18 patients; this subset reported drinking alcohol prior to WLS, but did not report a prior AUD diagnosis. Thus, 73% (n= 25) of this sample represents “new onset” cases of AUDs that first appeared after WLS. Patients met criteria for an AUD approximately three years post-WLS, and sought treatment an average of 5.4 years post WLS (Table 2). WLS patients were admitted to treatment had a mean age of 46, and were primarily non-Hispanic white and female (Table 2).

Ostlund and colleagues (2013) conducted largest medical record review to date about the putative association between WLS and substance abuse treatment, using a nationwide patient registry in Sweden from 1980 to 2006. Findings reveal that 11,115 patients underwent WLS, and patients who had the RYGB procedure were more likely to be hospitalized for an AUD than WLS patients who had the AGB or VGB procedures (hazard ratio, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.7-3.2). The prevalence of treatment admissions for alcohol use was not provided. Participants were on average 40 years old and predominantly female (Table 2). No race/ethnicity data were provided.

Finally, Fogger and colleagues (2012) present a sub-analysis of nurses participating in a monitoring program for nurses with problematic alcohol or illicit drug use. Of 173 respondents, 25 (14%) were WLS patients. The majority of participants (68%) indicated that their problem with substances began after they underwent WLS (Fogger, 2012). While frequency statistics of substances used were not reported, the nurses who had WLS were more likely to report problems with alcohol versus illicit drugs (24% versus 19%).

Illicit Drug Use

Six studies that met review criteria reported on illicit drug use data among post-operative WLS populations (Table 1 and 2). Five of these studies also reported on alcohol use among WLS patients; findings regarding alcohol use were previously described.

Longitudinal Studies

Conason and colleagues (2012) represent the only prospective assessment of pre- and post-surgical illicit drug use among post-WLS populations to date. There were no statistically significant differences in illicit drug use before and after WLS (Table 2). However, as described earlier, implications of this study are limited due to high-attrition experienced at follow-up (Table 2).

Cross-Sectional Studies

Two cross-sectional studies also reported a low prevalence of post-operative substance use disorders (SUDs) in post-operative WLS patients. These findings are summarized in Table 2.

Medical Record Reviews

Adams and colleagues (Adams et al., 2012) extracted illicit drug use information from medical charts that was prospectively collected pre- and post-WLS at a U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facility. Three of 61 patients had a lifetime, pre-surgical history of cocaine abuse. Post-WLS, one of those 3 patients was using cocaine again, as revealed by urine toxicology screen. Tedesco and colleagues (Tedesco et al., 2013) also reviewed medical records at a VA facility and found that 48 of 205 patients had a history of a pre-operative SUD. Post-WLS, two patients had a SUD, specifically methamphetamine use.

Finally, Omalu and colleagues (2007) reported on death rates and causes of death after WLS in the state of Pennsylvania over nine years. Among the 440 deaths, 14 (3%) were listed as being attributed to a non-suicidal drug-overdose, most of which occurred at least one year after surgery. While no other details are provided, this suggests an elevated rate of drug overdose deaths compared to the general population (Omalu, et al., 2007).

Substance use (alcohol and illicit drug use combined)

Three studies investigated post-surgical substance use disorders. Because the types of substances were never distinguished (i.e., alcohol, illicit drug, and/or tobacco use), alcohol use and illicit drug use were not separable. Reslan and colleagues (2014) examined 141 RYGB patients (Table 1) for pre- and post-operative “probable substance misuse.” It is important to note that the authors included tobacco, in addition to alcohol and illicit drugs, in their substance use index. The majority of the sample (80%) reported no substance misuse both before and after WLS. However, of the twenty patients (14%) who indicated post-surgical substance misuse, 70 % (n=14) did not report pre-operative substance misuse, representing new-onset post-WLS cases. Tobacco, alcohol, and sedatives were the most commonly reported “misused” substances (Reslan et al., 2014). Frequency statistics for each separate substance (i.e., tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs) were not indicated.

Ivezaj and colleagues (2014) reported on a similar patient sample, and found nearly identical rates of probable substance use disorders. The authors used the MAST-AD to assess for SUDs and never differentiated between alcohol and illicit drug use (Table 2). Correlates of post-operative SUDs included more years since WLS, more stressful events post-WLS, and more family members with SUD histories (Table 2; Ivezaj et al., 2014). Fowler and colleagues (2014) performed a secondary data analysis on Ivezaj et al.'s (2014) data (Table 1), and found that patients who reported having pre-surgical problems with foods that were a combination of high in sugar and low in fat, as well as high glycemic index foods (i.e., refined carbohydrates) were at greater risk for developing a “new” onset SUD after surgery (Table 2).

Conclusions

The most rigorous studies—those that were prospective, were longitudinal, and involved large samples of WLS patients—reveal that WLS patients who undergo the RYGB procedure are at a heightened risk for post-operative problematic alcohol use compared to (a) non-surgical controls (Svensson et al., 2013), and (b) patients undergoing other WLS procedures (King et al., 2012). In addition, a large-scale medical chart review of 11,115 WLS patients found that RYGB patients were more likely to seek in-patient treatment for AUDs than WLS patients who underwent other types of procedures (hazard ratio, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.7-3.2; Ostlund et al. 2013). Findings from two cross-sectional studies (Conason et al., 2012; Suzuki et al., 2012) also found elevated rates of alcohol use problems among RYGB patients. However, the existing literature is far from unequivocal. For example, Wee and colleagues (2014) found that over 70% of RYGB patients reported amelioration in high risk drinking behaviors one year after surgery, compared to only 48% of AGB patients.

As discussed earlier, physiologic changes that result from the RYGB procedure may offer a putative explanation for an increased vulnerability for post-surgical AUDs (Hagerdorn, et al., 2007; Klockhoff et al., 2002;Woodard et al., 2011). Common theories about the causes of these changes reflect anatomy after the gastric bypass, which allows for rapid absorption of alcohol into the blood stream. In fact, RYGB patients have demonstrated blood alcohol content over .08% after only one drink (Steffen et al., 2013). To date, this has not been found to be true for AGB patients.

Patient reports of increased alcohol sensitivity following the RYGB procedure are also documented in two of the studies reviewed here (Buffington, 2007; Ertelt et al., 2008). Increased alcohol sensitivity could potentially increase vulnerability for addiction or problematic use (Woodard et al., 2011). Pre-clinical research has also documented increased alcohol consumption in rats that underwent the RYGB procedure (Davis et al., 2012; Hajnal et al., 2012; Thanos et al., 2012).

For WLS patients overall, and not just RYGB patients, risk factors for post-surgical problematic alcohol use (i.e. high-risk drinking and/or AUDs) include a history of preoperative AUDs (Suzuki et al., 2012; King et al., 2012), male gender (King et al., 2012 & Svensson et al., 2013) younger age, (King et al. 2012), any pre-operative alcohol use (Svensson et al. 2013), regular (≥ 2 drinks per week) pre-operative alcohol use, (King et al. 2012), pre-operative tobacco use (King et al., 2012; Svensson, et al. 2013), pre-operative illicit drug use (King et al., 2012), and symptoms of ADHD (Alfonsson et al., 2014). Three studies also documented that WLS patients might be over-represented in substance use treatment facilities (Saules et al., 2010; Wiedemann et al., 2013; Cuellar-Barboza), with WLS patients more likely to seek treatment for alcohol use as opposed to illicit drug use (Saules et al., 2010; Wiedemann et al., 2013).

New onset cases of problematic alcohol use

Perhaps some of the most compelling findings from the previously cited studies include the documentation of “new” post-operative AUDs, meaning that WLS patients did not develop symptoms of AUDs until after surgery (Buffington, 2007; Cuellar-Barboza et al., 2014; Ertelt et al., 2008; Fowler et al., 2014; Mitchell et al. 2001; Reslan et al., 2014; Saules et al., 2010; Wee, et al. 2014; Wiedemann et al., 2013). While intriguing, the aforementioned finding comes from studies limited by small sample sizes, failure to use validated assessment instruments, and absence of a control comparison group. Also notable is that females over the age of 45 represent the prototypic participant across these studies, a demographic not commonly associated with problematic alcohol or drug use. The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) found that less than 2% of women from ages 45-60 met criteria for an AUD (Grant et al., 2004), and less than 1.6% of adults aged 45-59 met criteria for an AUD in the past 12 months according to the National Comorbidity Study (NCS-R; Kessler et al., 2005). Thus, It appears that the pro-typical post-WLS patient is remarkably at-risk for AOD problems during a remarkably low risk period in the lifespan.

Alcohol and Illicit Drug Use Disorder Trajectories

Several studies found that post-WLS patients who will have problems with alcohol/substances start experiencing problems a year or more post-surgery. Cuellar-Barboza et al., 2014; Saules et al., 2010; and Wiedemann et al., 2013 documented the significance of one-year post-WLS for symptoms of AUDs/SUDs; while, King and colleagues (2012) found the same two years post-WLS (Table 2).

Research Implications

The literature would benefit from the inclusion of younger and racially/ethnically diverse WLS patients in relation to substance use outcomes. While currently, non-Hispanic white females in their mid forties represent the majority of WLS patients (Sudan et al., 2014), younger and racially/ethnically diverse and male bariatric patients warrant inclusion in future research. Improved health outcomes and weight loss have been documented in younger populations (Messiah et al., 2013) and increases in weight loss have been associated with having WLS at a younger age (Contreras et al. 2013). Equally important, in the general population, younger adults (ages 18 to 35) are at an increased risk for demonstrating problematic alcohol use (Brown et al., 2008), and thus may be at elevated post-surgery risk for substance use problems. Thus, WLS patients in this age range could represent both an emerging population undergoing WLS, and an especially at-risk population for post-surgical alcohol use disorders.

Studies including ethnic/racial minority populations are also warranted. Non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics, and Native Americans/American Indians are disproportionately affected by obesity in the United States (Flegal et al., 2012; Schiller et al. 2012). These ethnic/racial populations have an over-representation of candidates for WLS and will likely represent an increasing demographic (Pickett-Blakely et al., 2012). Other than Conason et al. (2012), none of the studies attended to minority populations (Table 1). Furthermore, almost 40% of the studies reviewed did not include race/ethnicity information (Alfonsson et al., 2014; Buffington, 2007; Fogger et al., 2012; Macias & Leal, 2003; Mitchell et al., 2001; Ostlund et al., 2013; Svensson et al., 2013; Suzuki et al., 2012; Tedesco et al., 2013).

The literature also would benefit from longitudinal investigations of post-operative alcohol and illicit drug using reliable and validated measures. Moreover, many studies relied on retrospective report, which is only so accurate. Prospective studies assessing alcohol and illicit drug use at multiple points post-surgery also would make important contributions to the literature; such studies would help elucidate which and when WLS patients may be at highest risk for AUDs.

It would also be helpful for researchers to routinely obtain specific and separate alcohol and drug use data. Too many studies to date have collected and reported alcohol and drug use data in a single, combined variable. Physiological and psychological responses to alcohol and illicit drugs certainly vary, as do implications of using alcohol compared to illicit drugs. In addition, with the increasing legalization and decriminalization of medical marijuana, the implications of post-operative marijuana use should also be explored (Rummel & Heinberg, 2014).

The use of validated alcohol use disorder assessments is also warranted. Of the studies reviewed here, only 11 employed validated assessments, most commonly the AUDIT (Table 1). Illicit drug and alcohol use information should also be collected separately from clinical practices and not by treating clinicians to limit responses driven by social desirability (Ambwani et al., 2013). As a final note, many of the studies reviewed here relied on now outdated diagnostic criterion to assess alcohol abuse and dependence.

In conclusion, most of the research reviewed in this systematic review, including the best designed studies, suggests patients undergoing the RYGB procedure are at risk for post-operative AUDs. Additional research involving longitudinal designs, validated assessment instruments, investigation of large and diverse samples, and follow up after the two-year post-operative point, is warranted. Comparisons of post-operative AUDs across surgery groups is also needed to further elucidate the relationship between type of WLS and post-operative AUDs.

Acknowledgments

The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P20MD002288 and the Micah Batchelor Award for Excellence in Child Health Research supported the composition of this manuscript through their funding support of the authors. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Micah Batchelor Foundation.

References

- Abbatini F, Capoccia D, Casella G, Soricelli E, Leonetti F, Basso N. Long-Term Remission Of Type 2 Diabetes In Morbidly Obese Patients After Sleeve Gastrectomy. Surgery For Obesity And Related Diseases. 2013;9:498–502. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams CE, Gabriele JM, Baillie LE, Dubbert PM. Tobacco Use And Substance Use Disorders As Predictors Of Postoperative Weight Loss 2 Years After Bariatric Surgery. The Journal Of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2012;39:462–71. doi: 10.1007/s11414-012-9277-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Litten RZ, Fertig JB, Babor T. A Review Of Research On The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Audit) Alcoholism: Clinical And Experimental Research. 1997;21:613–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambwani S, Boeka AG, Brown JD, Byrne TK, Budak AR, Sarwer DB, Fabricatore AN, Morey LC, O'Neil PM. Socially Desirable Responding By Bariatric Surgery Candidates During Psychological Assessment. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9(2):300–5. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Mcgue M, Maggs J, Schulenberg J, Hingson R, Swartzwelder S, Martin C, Chung T, Tapert SF, Sher K, Winters KE, Lowman C, Murphy S. A Developmental Perspective On Alcohol And Youths 16 To 20 Years Of Age. Pediatrics. 2008;121:S290–S310. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, Jensen Md, Pories W, Fahrbach K, Schoelles K. Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review And Meta-Analysis. JAMA, The Journal Of The American Medical Association. 2004;292:1724. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffington C. Alcohol Use And Health Risks: Survey Results. Bariatric Times. 2007;4:21. [Google Scholar]

- Centers For Disease Control And Prevention, U.S. Department Of Health And Human Services. Vital Signs: Binge Drinking Among Women And High School Girls-United States. Morbidity And Mortality Weekly Report. 2013;62:1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitwood DD, Sanchez J, Comerford M, Mccoy CB. Primary Preventative Health Care Among Injection Drug Users, Other Sustained Drug Users, And Non-Users. Substance Use & Misuse. 2001;36:807–824. doi: 10.1081/ja-100104092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conason A, Teixeira J, Hsu CH, Puma L, Kanfo D, Geliebeter A. Substance Use Following Bariatric Weight Loss Surgery. Archives Of Surgery. 2012;148:145–50. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamasurg.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras JE, Santander C, Court I, Bravo J. Correlation Between Age And Weight Loss After Bariatric Surgery. Obesity Surg. 2013;23:1286. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-0905-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Zhou Y. Effectiveness of the Derived Alcohol Use Disorders Indentification Test (AUDIT-C) in Screening for Alcohol Use Disorders and Risk Drinking in the US General Population. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29(5):844–854. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000164374.32229.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JF, Schurdak JD, Magriss IJ, Mul JD, Grayson BE, Pfluger PT, Tschöp MH, Seeley RJ, Benoit SC. Gastric Bypass Surgery Attenuates Ethanol Consumption In Ethanol-Preferring Rats. Biological Psychiatry. 2012;72:354–360. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Cruz-Munoz N, Lopez-Mitnik G, Arheart KL, Miller TL, Lipshultz SE, Messiah SE. Effectiveness Of Bariatric Surgery In Reducing Weight And Body Mass Index Among Hispanic Adolescents. Obesity Surgery. 2013;23(2):150–156. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0730-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertelt TW, Mitchell JE, Lancaster K, Crosby RD, Steffen KJ, Marino JM. Alcohol Abuse And Dependence Before And After Bariatric Surgery: A Review Of The Literature And Report Of A New Data Set. Surg for Obesity And Related Disease. 2008;4(5):647–650. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogger SA. The Relationship Between Addictions And Bariatric Surgery For Nurses In Recovery. Perspectives In Psychiatric Care. 2012;48:10–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2010.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence Of Obesity And Trends In The Distribution Of Body Mass Index Among Us Adults, 1999-2010(Report) JAMA The Journal Of The American Medical Association. 2012;307(5):491. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerdorn JC, Encarnacion B, Brat GA, Morton JM. Does Gastric Bypass Alter Alcohol Metabolism? Surgery For Obesity And Related Diseases. 2007;3:543. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajnal A, Zharikov A, Polston JE, Fields MR, Tomasko J, Rogers AM, Volkow ND, Thanos PK. Alcohol Reward Is Increased After Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass In Dietary Obese Rats With Differential Effects Following Ghrelin Antagonism. Plos One. 2012;7(11):E49121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneghan HM, Cetin D, Navaneethan SD, Orzech N, Brethauer SA, Schauer PR. Effects Of Bariatric Surgery On Diabetic Nephropathy After 5 Years Of Follow-Up. Surgery For Obesity And Related Diseases. 2013;9(1):7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny PJ. Common cellular and molecular mechanisms in obesity and drug addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12(11):638–51. doi: 10.1038/nrn3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of general psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King WC, Chen J, Mitchell JE, Kalarchian MA, Steffen KJ, Engel SG, Courcoulas AP, Pories WJ, Yanovski SZ. Prevalence Of Alcohol Use Disorders Before And After Bariatric Surgery. JAMA : The Journal Of The American Medical Association. 2012;307(23):2516–2525. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klockhoff H, Näslund I, Jones AW. Faster Absorption Of Ethanol And Higher Peak Concentration In Women After Gastric Bypass Surgery. British Journal Of Clinical Pharmacology. 2002;54(6):587–591. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.01698.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lent MR, Hayes SM, Wood GC, Napolitano MA, Argyropoulos G, Gerhard GS, Foster GD, Still CD. Smoking And Alcohol Use In Gastric Bypass Patients. Eating Behaviors. 2013;14(4):460–463. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanick JI, Kushner RF, Sugerman HJ, Gonzalez-Campoy JM, Collazo-Clavell ML, Spitz AF, Apovian CM, Livingston EH, Brolin R, Sarwer DB, Anderson WA, Dixon J. American Association Of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, And American Society For Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery Medical Guidelines For Clinical Practice For The Perioperative Nutritional, Metabolic, And Nonsurgical Support Of The Bariatric Surgery Patient. Obesity. 2009;17(S1):S3–S72. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messiah SE, Lopez-Mitnik G, Winegar D, Sherif B, Arheart KL, Reichard KW, Michalsky MP, Lipshultz SE, Miller TL, Livingstone AS, De La Cruz Muñoz N. Changes In Weight And Co-Morbidities Among Adolescents Undergoing Bariatric Surgery: 1-Year Results From The Bariatric Outcomes Longitudinal Database. Surgery For Obesity And Related Diseases. 2013;9(4):503–513. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JE, Lancaster KL, Burgard MA, Howell M, Krahn DD, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Gosnell BA. Long-Term Follow-Up Of Patients' Status After Gastric Bypass. Obesity Surg. 2001;11(4):464. doi: 10.1381/096089201321209341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen NT, Masoomi H, Magno CP, Nguyen XT, Laugenour K, Lane J. Trends In Use Of Bariatric Surgery, 2003–2008. Journal Of The American College Of Surgeons. 2011;213(2):261–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odom J, Zalesin KC, Washington TL, Miller WW, Hakmeh B, Zaremba DL, Altattan M, Balasubramaniam M, Gibbs DS, Krause KR, Chengelis DL, Franklin BA, Mccullough PA. Behavioral Predictors Of Weight Regain After Bariatric Surgery. Obesity Surgery. 2010;20(3):349–356. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9895-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omalu BI, Ives DG, Buhar AM, Lindner JL, Schauer PR, Wecht CH, Kuller LH. Death Rates And Causes Of Death After Bariatric Surgery For Pennsylvania Residents, 1995 To 2004. Archives Of Surgery. 2007;142(10):923. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.10.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostlund MP, Backman O, Marsk R, Stockeld D, Lagergren J, Rasmussen F, Näslund E. Increased Admission For Alcohol Dependence After Gastric Bypass Surgery Compared With Restrictive Bariatric Surgery. JAMA Surgery. 2013;148(4):374–377. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickett-Blakely OE, Huizinga MM, Clark JM. Sociodemographic Trends In Bariatric Surgery Utilization In The USA. Obesity Surgery. 2012;22:838. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0629-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raebel MA, Newcomer SR, Reifler LM, Bourdreau D, Elliott TE, Debar L, Ahmed A, Pawloski PA, Fisher D, Donahoo WT, Bayliss EA. Chronic Use Of Opioid Medications Before And After Bariatric Surgery. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1369. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reslan S, Saules KK, Greenwald MK, Scuh LM. Substance Misuse Following Roux-En-Y-Gastric Bypass Surgery Substance Use And Misuse. 2014;49:405–417. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.841249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rummel CM, Heinberg LJ. Assessing Marijuana Use In Bariatric Surgery Candidates: Should It Be A Contradiction? Obesity Surgery. 2014;10:1764–70. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1315-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saules KK, Wiedemann A, Ivezah V, Hopper JA, Foster-Hartsfield J, Schwartz D. Bariatric Surgery History among Substance Abuse Treatment Patients: Prevalence and Associated Features. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2010;6:615–621. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. NSDUH Series H-48. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4863. [Google Scholar]

- Sudan R, Winegar D, Thomas S, Morton J. Influence of ethnicity on the efficacy and utilization of bariatric surgery in the USA. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2014;18(1):130–136. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2368-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller J, Lucas J, Peregoy J. Summary Of Health Statistics Of U.S. Adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2011. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2012;10:256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen KJ, Engel SG, Pollert GA, Li C, Mitchell JE. Blood Alcohol Concentrations Rise Rapidly And Dramatically After Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass. Surgery For Obesity And Related Diseases. 9:470–473. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki J, Haimovici F, Chang G. Alcohol Use Disorders After Bariatric Surgery. Obesity Surgery. 2012;22(2):201–207. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0346-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson P, Anveden Å, Romeo S, Peltonen M, Ahlin S, Burza MA, Carlsson B, Jacobson P, Lindroos A, Lönroth H, Maglio C, Näslund I, Sjöholm K, Wedel H, Söderpalm B, Sjöström L, Carlsson LMS. Alcohol Consumption And Alcohol Problems After Bariatric Surgery In The Swedish Obese Subjects Study. Obesity. 2013;21(12):2444–2451. doi: 10.1002/oby.20397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedesco M, Hua WQ, Lohnberg JA, Bellatorre N, Eisenberg D. A Prior History Of Substance Abuse In Veterans Undergoing Bariatric Surgery. Journal Of Obesity. 2013;2013:740312. doi: 10.1155/2013/740312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanos PK, Subrize M, Delis F, Cooney RN, Culnan D, Sun M, Wang G, Volkow ND, Hajnal A. Gastric Bypass Increases Ethanol And Water Consumption In Diet-Induced Obese Rats. Obesity Surgery. 2012;22(12):1884–1892. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0749-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wee CC, Mukamal KJ, Huskey KW, Davis RB, Colten ME, Bolcic-Jankovic D, Apovian CM, Jones DB, Blackburn GL. High Risk Alcohol Use After Weight Loss Surgery. Surg Obes and Relat Dis. 2014;10(3):508–13. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodard GA, Downey J, Hernandez-Boussard T, Morton JM. Impaired Alcohol Metabolism After Gastric Bypass Surgery: A Case-Crossover Trial. Journal Of The American College Of Surgeons. 2011;212(2):209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]