Abstract

Treatment with a mandibular advancement device (MAD) is recommended for mild obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), primary snoring and as a secondary option for Continuous Positive Airway Pressure, because it has better adherence and acceptance. However, edentulous patients do not have supports to hold the MAD. This study aimed to present a possible to OSA treatment with MAD in over complete upper and partial lower dentures. The patient, a 38-year-old female with mild OSA, was treated with a MAD. The respiratory parameter, such as apnea–hypopnea index, arousal index and oxyhemoglobin saturation was improved after treatment.

Keywords: Mandibular advancement device, Prothesis

1. Introduction

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) is a respiratory sleep disorder characterized by partial and/or complete obstruction of the upper airway [1]. OSA is highly prevalent, affecting up to 32.8% of the adult population in the São Paulo city [2].

The most common treatments for OSA include Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) and oral appliances (OA). CPAP is used as the first option in severe OSA because it normalizes respiratory parameters [3]. However, oral appliances are recommended for milder cases, such as primary snoring and mild OSA, or as a secondary treatment for CPAP or alternative treatment in CPAP failures [4].

OAs can be divided into two groups: mandibular advancement devices (MADs), which are attached to the teeth and move the mandible anteriorly, and tongue retaining devices, which use suction to position the tongue anteriorly inside a bulb [5]. MADs have higher success and compliance rates than tongue retaining devices [5] and have more scientific support for their use [6].

MADs are anchored to the teeth; therefore, their efficacy is directly related to the retention of the device to the dental arches [7]. Contraindications for treatment with these appliances include oral conditions with less than 10 teeth per arch [4], because this condition leads to lower retention and consequently failure of the treatment.

Importantly, Brazil has a large number of lost teeth and edentulous people [8,9], and this population is contraindicated for MAD use due to total and/or partial tooth loss. This case report contains an alternative treatment using a MAD constructed on a complete upper and partial lower prosthesis in a patient with mild OSA.

2. Case report

Patient NPDSD, a 38-year-old female, was referred to the AFIP Dental Sleep Clinic with a diagnosis of mild OSA (AHI=12.5). During anamnesis, the patient reported gagging and interrupted breathing during sleep. She complained of agitated sleep, tiredness after waking, and excessive daytime sleepiness and the Epwoth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) score was 8. Her main complaint was loud snoring.

The full night polysommnography was performed using a digital system (EMBLA (R) S7000, Embla System, Inc., Broomfield, CO., USA) and according to Academy American Manual (2007) [10]. The scoring of hypopnea events was made according to the alternative rules [10].

During a clinical examination, the patient showed a body mass index (BMI) of 29.8 kg/m2 and neck circumference of 38 cm. The oral examination showed complete upper denture, and a partial lower prosthesis constructed eight months before. The seven remaining teeth were a good periodontal condition and did not have caries. The alveolar ridge was good bone support and had a healthy aspect. The anchoring and stability of the prosthesis were evaluated and was satisfactory to do anchoring and stability of the MAD.

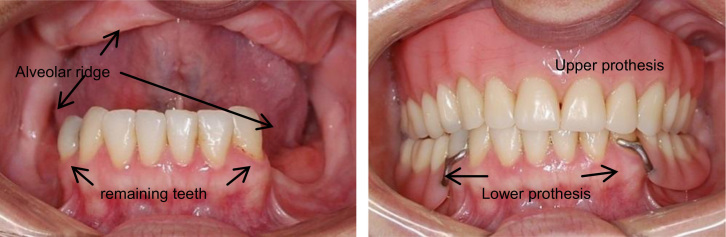

The patient was informed that the treatment would be a therapeutic trial, and there was a possibility that the treatment would fail. As the amount of force that the device would apply to the prosthesis was unknown we did not have sure if the MAD would move these prothesis. Fig. 1 shows the oral condition of the patient with and without the prosthesis installed.

Fig. 1.

The intraoral condition with and without the prothesis.

We planned to confection the PM positioner appliance that it is a custom-made titratable MAD and does not have laterality, which could produce less rocking force on the prosthesis, leading to better stability.

Her prior dental history was requested, including photographs, panoramic x-rays, and lateral teleradiography. Next, molds were taken with the prosthesis in the mouth, and register the protrusion measured using a George Gauge. The maximum protrusion (from the maximum posterior contact to the maximum tolerable protrusion) was 7 mm. The appliance was set to 50% when it was installed and advanced by 1 mm per by week until the snoring complaint was over. The advanced was finish at 100% of maximum tolerable protrusion, at 7 mm. She was submitted to a polysomnography after 5 months with a maximum tolerable protrusion position. Fig. 2 shows the patient with the MAD appliance installed.

Fig. 2.

Patient with dentures and MAD installed.

The treatment resulted in improvement on subjective sleepiness, ESS score was 4, on fatigue report and subjective and objective quality of sleep. On the polysomnogrpy parameters, the treatment decrease a sleep latency, REM latency, arousal index, AHI and increased of percentage of REM and N3 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive data.

| Variables | Pre-treatment | Post-treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Sleep latency (min) | 31.5 | 8.9 |

| REM latency (min) | 226.2 | 143.5 |

| Sleep efficiency (%) | 82.9 | 86.2 |

| N1 (%) | 4.9 | 5.1 |

| N2 (%) | 58.8 | 44.4 |

| N3 (%) | 15.1 | 25.8 |

| REM (%) | 20.7 | 24.7 |

| Arousal index | 14.4 | 1.7 |

| AHI | 12.5 | 0.0 |

| AI | 0.6 | 0.0 |

| HI | 11.9 | 0.0 |

| Minimum oxyhemoglobin saturation | 92 | 93 |

AHI=apnea–hypopnea index, AI=apnea index and HI=hypopnea index.

3. Discussion

The present study reports a successful treatment using a MAD constructed on a complete upper and partial lower prosthesis. This report is important because it broadens the potential uses of MAD appliances.

Treatment of edentulous patients with mild OSA is normally limited to CPAP or tongue retainers, which have low compliance [5,11]. The prevalence of OSA increases with age [2], and the prevalence of edentulous individuals is also high in the elderly population [8]. Using a MAD on a prosthesis is an alternative, as it is a low-cost treatment and does not require a power source [4].

Even though a tongue retainer does not require dental support and is normally recommended for edentulous individuals, it has low compliance and produces several side effects, including irritation of the soft tissues and excess drooling [5]. In a randomized crossover study by Deane et al. [5], 91% of the patients preferred a MAD over a tongue retaining device and were more satisfied with MAD use. In this study, tongue retainer had a compliance rate of 27.3% for use more than six hours per night, while MAD showed a compliance rate of 81.8%, [5].

There are few studies in the literature that address the treatment of edentulous individuals using a MAD, and those that do exist are limited to case reports. The majority of the studies support the device on the alveolar ridge [12–14] or on the tongue retainer flange [15]. Others build the device over a complete upper prosthesis [16] or on complete upper and lower prostheses [17]. Unlike previous studies, the present study was performed on a complete upper and partial lower prosthesis.

The ideal MAD treatment in patients with few or no teeth is to construct this device on previously installed implants, thus eliminating side effects related to occlusal changes and discomfort on the alveolar ridge. However, for the majority of the population, this treatment is impractical due to its high cost and because it is a surgical procedure.

A MAD installation on prosthesis should include frequent follow-up appointments to verify absorption of the edge and consequent loss of stability of the prosthesis. Periodic analyses are necessary, as the force exerted by the MAD may increase bone reabsorption, causing the OSA treatment to fail. When there are few teeth, dental side effects should be evaluated closely, because the force may be improve more dental side-effect. As there are few articles that address MAD use over a prosthesis, with none discussing long-term results. It becomes necessary.

4. Conclusion

Treatment with mandibular advancement device over prostheses may be possible. However it is necessary broad oral assessment, including mucosa, teeth and stability of prosthesis. Monitoring of possible side effects it is necessary to treatment at long time.

Acknowledgments

AFIP

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Brazilian Association of Sleep.

References

- 1.AAMS. Medicine A-AAoS. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders: diagnostic and coding manual. Westchester: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005.

- 2.Tufik S., Santos-Silva R., Taddei J.A., Bittencourt L.R. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in the Sao Paulo Epidemiologic Sleep Study. Sleep Med. 2010;11:441–446. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.C.A. Kushida, M.R Littner, M. Hirshkowitz, T.I. Morgenthaler, C.A. Alessi, D. Bailey. Practice parameters for the use of continuous and bilevel positive airway pressure devices to treat adult patients with sleep-related breathing disorders. Sleep. 2006;29:375–380. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.C.A. Kushida, T.I. Morgenthaler, M.R. Littner, C.A. Alessi, D. Bailey, J. Coleman. Practice parameters for the treatment of snoring and Obstructive Sleep Apnea with oral appliances: an update for 2005. Sleep. 2006;29:240–243. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.2.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.S.A. Deane, P.A. Cistulli, A.T. Ng, B. Zeng, P. Petocz, M.A. Darendeliler. Comparison of mandibular advancement splint and tongue stabilizing device in obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep. 2009;32:648–653. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.5.648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.A. Anandam, M. Patil, M. Akinnusi, P. Jaoude, A.A El-Solh. Cardiovascular mortality in obstructive sleep apnoea treated with continuous positive airway pressure or oral appliance: an observational study. Respirology. 2013;19:1184–1190. doi: 10.1111/resp.12140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vanderveken O.M., Van de Heyning P., Braem M.J. Retention of mandibular advancement devices in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: an in vitro pilot study. Sleep Breath. 2014;18:313–318. doi: 10.1007/s11325-013-0886-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piuvezam G., de Lima K.C. Self-perceived oral health status in institutionalized elderly in Brazil. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55:5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2011.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rihs L.B., da Silva D.D., de Sousa M.a.L. Dental caries and tooth loss in adults in a Brazilian southeastern state. J Appl Oral Sci. 2009;17:392–396. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572009000500008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iber C A-IS, Chesson A.L., Jr., Quan S.F. American Academy of Sleep Medicine; Westchester, IL: 2007. The AAM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: rules, terminology and technical specifications. [Google Scholar]

- 11.C.L. Phillips, R.R Grunstein, M.A. Darendeliler, A.S. Mihailidou, V.K. Srinivasan, B.J. Yee. Health outcomes of continuous positive airway pressure versus oral appliance treatment for obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:879–887. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201212-2223OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.B. Piskin, F. Sentut, H. Sevketbeyoglu, H. Avsever, K. Gunduz, M. Kose. Efficacy of a modified mandibular advancement device for a totally edentulous patient with severe obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2010;14:81–85. doi: 10.1007/s11325-009-0273-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.T. Ogawa, T. Ito, M.V. Cardoso, T. Kawata, K. Sasaki. Oral appliance treatment for obstructive sleep apnoea patients with severe dental condition. J Oral Rehabil. 2011;38:202–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2010.02138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keyf F., Ciftci B., Fırat Güven S. Management of obstructive sleep apnea in an edentulous lower jaw patient with a mandibular advancement device. Case Rep Dent. 2014:1–4. doi: 10.1155/2014/436904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurtulmus H., Cotert H.S. Management of obstructive sleep apnea in an edentulous patient with a combination of mandibular advancement splint and tongue-retaining device: a clinical report. Sleep Breath. 2009;13:97–102. doi: 10.1007/s11325-008-0201-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giannasi L.C., Magini M., de Oliveira C.S., de Oliveira L.V. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea using an adjustable mandibular repositioning appliance fitted to a total prosthesis in a maxillary edentulous patient. Sleep Breath. 2008;12:91–95. doi: 10.1007/s11325-007-0134-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelogi S., Porwal A., Naveen H. Modified mandibular advancement appliance for an edentulous obstructive sleep apnea patient: a clinical report. J Prosthodont Res. 2011;55:179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jpor.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]