Abstract

Because hearts with a temporally induced knockout of acyl-CoA synthetase 1 (Acsl1T−/−) are virtually unable to oxidize fatty acids, glucose use increases 8-fold to compensate. This metabolic switch activates mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), which initiates growth by increasing protein and RNA synthesis and fatty acid metabolism, while decreasing autophagy. Compared with controls, Acsl1T−/− hearts contained 3 times more mitochondria with abnormal structure and displayed a 35–43% lower respiratory function. To study the effects of mTORC1 activation on mitochondrial structure and function, mTORC1 was inhibited by treating Acsl1T−/− and littermate control mice with rapamycin or vehicle alone for 2 wk. Rapamycin treatment normalized mitochondrial structure, number, and the maximal respiration rate in Acsl1T−/− hearts, but did not improve ADP-stimulated oxygen consumption, which was likely caused by the 33–51% lower ATP synthase activity present in both vehicle- and rapamycin-treated Acsl1T−/− hearts. The turnover of microtubule associated protein light chain 3b in Acsl1T−/− hearts was 88% lower than controls, indicating a diminished rate of autophagy. Rapamycin treatment increased autophagy to a rate that was 3.1-fold higher than in controls, allowing the formation of autophagolysosomes and the clearance of damaged mitochondria. Thus, long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase isoform 1 (ACSL1) deficiency in the heart activated mTORC1, thereby inhibiting autophagy and increasing the number of damaged mitochondria.—Grevengoed, T. J., Cooper, D. E., Young, P. A., Ellis, J. M., Coleman, R. A. Loss of long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase isoform 1 impairs cardiac autophagy and mitochondrial structure through mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 activation.

Keywords: heart metabolism, glucose metabolism, lipid metabolism, β-oxidation, ATP synthase

The heart alters its substrate use to meet the constant high demand for energy. For example, whereas the heart normally obtains 60–90% of its energy from very LDL-derived fatty acids (1), feeding or hypoxia can increase the use of glucose, whereas fasting can increase the use of amino acids and ketone bodies (2). In diabetes, the impaired uptake of glucose increases the use of fatty acids (3, 4), and conversely, glucose use increases with both heart failure and the pathologic hypertrophy caused by pressure overload (5–8). Because it is unclear whether the switch in substrate use in each of these states is compensatory or pathologic, we asked whether predominant glucose use, in the absence of other cardiac dysfunction, would be detrimental.

Acyl-CoA synthetases (ACSLs) convert fatty acids to acyl-CoAs, which can then be oxidized in the mitochondria to produce energy, incorporated into triacylglycerol (TAG) for storage, or incorporated into phospholipids for membrane biogenesis. Of the 5 long-chain mammalian ACSL isoforms, long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase isoform 1 (ACSL1) is the major isoform in the heart, accounting for 90% of total ACSL activity. In the temporally induced mouse model deficient in ACSL isoform-1 (Acsl1T−/− mice), fatty acid oxidation is diminished by >90%, and glucose use increases 8-fold to compensate for this loss (9).

To study the consequences of the switch from fatty acid to glucose use in Acsl1T−/− hearts, we focused on the effects of the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), which is activated by high glucose flux in hearts (10, 11). Within 10 wk of inducing the knockout, hearts lacking ACSL1 develop mTORC1-dependent hypertrophy (12). mTORC1 activation has many consequences in cells, including stimulation of growth and protein synthesis (13, 14), regulation of lipid metabolism (15, 16), and inhibition of autophagy (17). Inhibition of mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) is associated with longer life span (18), but total loss of mTOR in the heart inhibits mitochondrial respiratory function and causes heart failure (16). Although short-term activation of mTOR increases mitochondrial respiration and biogenesis in cultured cells (19–21), mTORC1 inhibition of autophagy can allow damaged mitochondria to accumulate. Cardiac mitochondrial DNA and proteins have half-lives of less than 1 wk, indicating a high rate of turnover (22, 23). Rapid removal of damaged mitochondria is particularly important in cardiomyocytes that have a long life span and a high demand for energy. Impaired removal of damaged mitochondria can exacerbate damage after ischemia (24) or myocardial infarction (25) and cause heart failure (26, 27). In the present study, we examined the effects of chronic mTORC1 activation on the number and structure of mitochondria and on the function of the electron transport chain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Unless otherwise indicated, reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Radiolabeled substrates (2-Br-[1-14C]palmitate, [1-14C]palmitate, and [2-14C]pyruvate) were purchased from Perkin-Elmer (Waltham, MA, USA). Trypsin and soybean trypsin inhibitor were from Worthington Biochemical (Lakewood, NJ, USA).

Animal care and diets

All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Mice were housed under a 12 h light–dark cycle with free access to food and water. Unless otherwise specified, mice were fed a purified low-fat diet (DB12451B; Research Diets Inc., New Brunswick, NJ, USA). A multitissue knockout of ACSL1 was achieved by mating mice with LoxP sequences flanking exon 1 of the Acsl1 gene to animals expressing a tamoxifen-inducible Cre driven by a ubiquitous promoter enhancer (9). Between 6 and 8 wk of age, Acsl1T−/− and littermate Acsl1flox/flox (control) mice were injected intraperitoneally on 4 consecutive days with tamoxifen (75 μg/g body weight) dissolved in corn oil. All studies were performed with male mice 20 wk after tamoxifen administration, and tissues were collected after a 4 h food withdrawal, unless otherwise specified. The mice were deeply anesthetized with Avertin (39 ml PBS, 1 ml tert-amyl alcohol, 1 g 2,2,2-tribromoethanol) and tissues were snap frozen by immersion in liquid nitrogen. For mTORC1 inhibition studies, rapamycin (1 mg/kg in PBS, pH 7.4/2% ethanol, 2.5% Tween 20/2.5% (polyethylene glycol 400), or vehicle alone was injected intraperitoneally daily for 7 or 14 d, starting 18 or 19 wk after tamoxifen treatment. A short rapamycin treatment was chosen to lessen the impaired insulin secretion and glucose tolerance observed with chronic rapamycin treatment (12, 28, 29). For autophagic flux studies, chloroquine (60 mg/kg in PBS, pH 7.4) was injected intraperitoneally for 7 d.

ACSL activity assay

ACSL-specific activity was measured as described elsewhere (9). Briefly, homogenized tissues were centrifuged at 100,000 g for 1 h at 4°C to isolate total membrane fractions. Protein (1–6 µg) was incubated with 50 µM [1-14C]palmitate, 10 mM ATP, 250 µM CoA, 5 mM DTT, and 8 mM MgCl2 in 175 mM Tris, pH 7.4 at room temperature for 10 min to measure initial rates. The enzyme reaction was stopped with 1 ml of Dole’s solution (heptane:isopropanol:1M H2SO4; 80:20:1, v/v). Heptane (2 ml) and 0.5 ml of water were added to separate phases. Radioactivity of the acyl-CoAs in the aqueous phase was measured in a liquid scintillation counter.

Metabolic phenotyping

To quantify fatty acid uptake, 1.5 µCi 2-Br-[1-14C]palmitate complexed to bovine serum albumin was injected retro-orbitally. Tail blood was collected 5 min later, and tissues were collected 30 min after injection. Tissues were homogenized in water and radioactivity per milligram of tissue was quantified relative to radioactivity in blood. To analyze fatty acid oxidation and tricarboxylic acid cycle activity, respectively, [1-14C]palmitate and [2-14C]pyruvate oxidation were measured in isolated mitochondria in separate experiments as described elsewhere (9). Ventricle TAG was measured using a colorimetric kit (Sigma-Aldrich). Tissues for glycogen measurement were collected at 7:00 am (fed) or after 4 h of food withdrawal and were homogenized in 1 N HCl. A portion was immediately neutralized to measure free glucose. The remaining homogenate was heated to 95°C for 90 min to hydrolyze glycogen, then neutralized with 1 N NaOH and centrifuged at 14,000 g for 10 min. A colorimetric kit was used to measure glucose in the supernatant (Wako, Richmond, VA, USA).

Electron microscopy

Mice were withheld food for 4 h. Hearts were first perfused with PBS and then with freshly made 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.15 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. Left ventricular tissue was prepared for transmission electron microscopy and imaged (30). Mitochondrial area was quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) in 4 to 7 images, counting at least 1000 mitochondria per animal. Abnormal mitochondria were defined as mitochondria with vacuoles, inclusions, or disrupted cristae.

Mitochondrial function

To isolate mitochondria, hearts were minced in 0.125 mg/ml trypsin in homogenization buffer (0.25 M sucrose, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4). Soybean trypsin inhibitor (0.65 mg/ml) was added, and tissues were homogenized with 10 up-and-down strokes in a Teflon-glass homogenizing vessel (Potter-Elvehjem, Pro Scientific Inc., Oxford, CT, USA) and then centrifuged at 500 g for 5 min to remove nuclei and unbroken cells. Mitochondria were isolated by centrifuging at 10,000 g for 15 min and washed twice with homogenization buffer. The mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in mitochondrial assay buffer [70 mM sucrose, 220 mM mannitol, 10 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.2% bovine serum albumin, 25 mM BES (N,N-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid), pH 7.0]. The function of isolated mitochondria was assessed using a Seahorse XF24 Analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience, North Billerica, MA, USA) with 5 mM pyruvate and 5 mM malate as substrates. Mitochondria (15 µg of protein) were stimulated in succession with 100 µM ADP, 1 µg/ml oligomycin, 4 µM carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy)-phenylhydrazone (FCCP), and 4 µm antimycin A. To measure mitochondrial electron transport chain complex formation and complex V activity, mitochondrial proteins were prepared and separated by clear native electrophoresis. ATP hydrolysis activity of complex V was measured as described elsewhere (31).

Gene expression analysis

Total RNA and DNA were simultaneously isolated from heart ventricles (AllPrep RNA/DNA Mini kit; Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). cDNA was synthesized (iScript cDNA Synthesis kit, BioRad), and 10 ng of cDNA was added to each qPCR reaction with SYBR Green (iTaq Universal SYBR; BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) and used to detect amplicons with primers specific to the gene of interest quantified using a qPCR thermocycler (BioRad). Results were normalized to the housekeeping gene Gapdh and expressed as arbitrary units of 2−ΔΔCt relative to the control group.

Immunoblots

Total protein lysates were isolated in lysis buffer (250 mM sucrose, 20 mM Tris, 1% Triton X-100, 50 mM NaF, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM Na4P2O7, plus protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). To isolate cytosol, homogenized tissue was centrifuged for 1 h at 100,000 g at 4°C. Immunoblots were run under standard conditions. Primary antibodies were purchased from the indicated companies: phosphorylated-p70 S6 kinase (Thr389), p70 S6 kinase (S6K), phosphorylated-4E-BP1 (Thr37/46), 4E-BP1, Parkin, and ACSL1 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), GAPDH (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), microtubule-associated protein light chain 3B (LC3B) (Sigma-Aldrich), and p62 (Abnova, Taipei City, Taiwan).

Statistics

Data are presented as means ± se for each treatment group. Differences between groups were evaluated by 2-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple-comparison posttests. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 6.0; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Differences between means with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Loss of cardiac ACSL1 decreased the use of fatty acids and increased the use of glucose

Hearts lacking ACSL1 have been previously characterized at 2 and 10 wk after induction of the knockout with tamoxifen (9). To examine the long-term effects of ACSL1 deficiency, we evaluated mice at 20 wk after tamoxifen was given. To confirm that the metabolic phenotype persisted, salient points were re-examined. Similar to the previous report, ACSL1 protein and mRNA remained absent from Acsl1T−/− hearts 20 wk after tamoxifen treatment (Fig. 1A, B). In Acsl1T−/− ventricles and Acsl1T−/− hearts, Acsl3 mRNA expression was 4.5-fold higher, Acsl6 mRNA was 39% lower (Fig. 1B), and ACSL-specific activity was 86% lower (Fig. 1C), suggesting that any compensation by other ACSL isoforms had done little to increase ACSL activity. We measured mitochondrial oxidation of [1-14C]palmitate to both CO2 and acid soluble metabolites, which are measures of complete and incomplete oxidation, respectively. The diminished activation of fatty acids to acyl-CoAs resulted in 94% lower [1-14C]palmitate oxidation than in control cardiac mitochondria (Fig. 1D). In contrast to hearts deficient in carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (32), the minimal oxidation of fatty acids in Acsl1T−/− hearts did not result in cardiac TAG accumulation (Fig. 1E). This lack of TAG accumulation was likely due to diminished fatty acid uptake; as measured with the nonoxidizable fatty acid analog 2-Br-[1-14C]palmitate, uptake was 76% lower in Acsl1T−/− hearts than in controls (Fig. 1F). The addition of coenzyme A to the fatty acid permits vectorial transport by both trapping the fatty acid within the cell and lowering its effective concentration (33). Even though fatty acid oxidation was low in Acsl1T−/− hearts compared with controls, phosphorylated (activated) AMPK was reduced in Acsl1T−/− hearts, consistent with the production of adequate energy to maintain a low AMP/ATP ratio (Fig. 1G). Despite the impaired fatty acid oxidation rate, systolic function remained normal in Acsl1T−/− hearts (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Loss of cardiac ACSL1 decreased fatty acid use and increased the use of glucose. A) ACSL1 protein in ventricles 20 wk after tamoxifen-induced knockout of Acsl1. B) Gene expression in ventricles (n = 6). C) ACSL specific activity in ventricular membranes (n = 3). D) [1-14C]palmitate oxidation to CO2 or acid-soluble metabolites (ASM) in isolated cardiac mitochondria (n = 4). E) TAG content in ventricles (n = 5). F) In vivo 2-Br-[1-14C]palmitate uptake in ventricles (n = 5). G) Phosphorylated AMPK relative to total AMPK in ventricles (n = 4–5). H) [2-14C]pyruvate oxidation to CO2 in isolated cardiac mitochondria (n = 5). I) Tissues were collected from female mice 10 wk after tamoxifen at 7:00 am (fed), or at 11:00 am after 4 h of withholding food (unfed). Glucose from glycogen was measured after acid hydrolysis (n = 4). *P < 0.05.

To compensate for the low fatty acid oxidation, glucose use increased in Acsl1T−/− hearts. Compared with controls, the oxidation of [2-14C]pyruvate was 2-fold higher in Acsl1T−/− cardiac mitochondria, consistent with increased flux through the tricarboxylic acid cycle (Fig. 1H). Acsl1T−/− hearts stored 70% more glycogen than controls during feeding and used the extra glycogen during a 4 h food withdrawal. Livers in Acsl1T−/− mice, which recover ACSL1 expression (9), contained normal amounts of glycogen during feeding, but rapidly lose 35% during a 4 h food withdrawal (Fig. 1I), suggesting that the rate of glycogen use was more rapid in Acsl1T−/− mice. Together, these observations show that the metabolic changes previously detected in Acsl1T−/− hearts persist (9), and that 20 wk after loss of ACSL1, cardiac metabolism vastly favored glucose metabolism.

Two weeks of rapamycin treatment inhibited mTORC1 activation in Acsl1T−/− hearts

mTORC1 is activated in Acsl1T−/− 10 wk after tamoxifen-mediated induction of the knockout (9). We examined phosphorylation of 2 mTORC1 targets, S6K and 4E-BP1, to confirm that mTORC1 remained activated after an additional 10 wk. Treatment of in Acsl1T−/− hearts with the mTORC1 inhibitor rapamycin for 2 wk repressed mTORC1-mediated phosphorylation of both S6K and 4E-BP1 (Fig. 2A), decreased the size of both control and Acsl1T−/− hearts (Fig. 2B), and normalized Acsl1T−/− heart size. In Acsl1T−/− hearts, 2 wk of rapamycin treatment lowered the expression of fetal gene markers of pathologic hypertrophy (aSka, Bnp) and Acsl3, the fetal cardiac ACSL isoform (Fig. 2C). Ten weeks of rapamycin treatment did not alter total ACSL specific activity (12), and 2 wk of rapamycin treatment did not alter Acsl1 gene expression in either the control or Acsl1T−/− hearts (Fig. 2C). These changes confirmed that activated mTORC1 had caused the hypertrophy observed in Acsl1T−/− hearts (12).

Figure 2.

Two weeks of rapamycin treatment inhibited mTORC1 activation in Acsl1T−/− hearts. Control and Acsl1T−/− mice were treated with vehicle or 1 mg/kg rapamycin daily for 2 wk. A) Representative immunoblot of phosphorylation of mTORC1 targets, S6K and 4E-BP1, in ventricles. B) Heart weight normalized to body weight (n = 5–8). C) Gene expression in ventricles from mice treated with vehicle or rapamycin for 2 wk (n = 3–5). Rapa, rapamycin; Veh, vehicle. *P < 0.05 comparing genotype. #P < 0.05 comparing treatment.

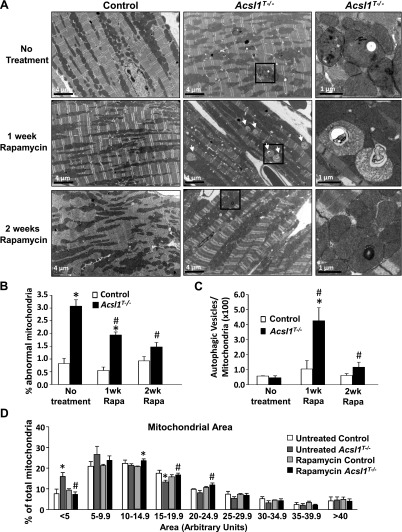

mTORC1 inhibition improved mitochondrial structure in Acsl1T−/− hearts

Ten weeks after the knockout was induced with tamoxifen, Acsl1T−/− ventricles contained an increased number of mitochondria, but no difference in mitochondrial structure was observed (9). Twenty weeks after tamoxifen, however, electron microscopy showed that 3 times more abnormal mitochondria were present in Acsl1T−/− ventricles (Fig. 3A, B). Abnormal mitochondria were defined as those containing vacuoles, inclusions, or disrupted cristae. No difference in glycogen content (as noted in Fig. 1) was observed because the hearts were collected after a 4 h food withdrawal when Acsl1T−/− heart glycogen content has normalized (Fig. 1I). Because mTORC1 inhibits autophagy (17), we questioned whether the mitochondria with abnormal structure could be cleared by relieving a block on autophagy. One week of rapamycin treatment had no observable effect on mitochondria in control hearts, but dramatically increased the number of autophagic vesicles in Acsl1T−/− hearts (Fig. 3C). After 2 wk of rapamycin treatment, most of the autophagic vacuoles had disappeared, and the Acsl1T−/− hearts contained significantly fewer abnormal mitochondria and autophagic vesicles (Fig. 3B, C). These data strongly suggest that activated mTORC1 had inhibited autophagy, thereby impairing the removal of damaged mitochondria. Quantification of mitochondrial area revealed that, compared with controls, Acsl1T−/− hearts contained twice as many very small mitochondria (area < 5 arbitrary units) and fewer large mitochondria (area of 15–19.9 and 20–24.9 arbitrary units) (Fig. 3D); these size changes were normalized by rapamycin treatment. Thus, loss of ACSL1 caused structurally abnormal mitochondria to accumulate and inhibition of mTORC1 normalized both mitochondrial size and appearance.

Figure 3.

mTORC1 inhibition improved mitochondrial structure in Acsl1T−/− hearts. A) Representative electron microscopy images of left ventricles for untreated mice and mice treated daily with rapamycin for 1 or 2 wk; ×5000 or ×20,000 magnification. White arrows indicate autophagic vesicles. B) Abnormal mitochondria in untreated mice or mice treated with rapamycin for 1 or 2 wk relative to total mitochondria (n = 3). Abnormal mitochondria were defined as those containing vacuoles, inclusions, or disrupted cristae. C) Autophagic mitochondria relative to total mitochondria after 1 or 2 wk of rapamycin treatment (n = 3). D) Mitochondrial area (n = 3). Mitochondrial area was quantified using ImageJ software for at least 1000 mitochondria per heart (4–7 images). Rapa, rapamycin. *P < 0.05 comparing genotype. #P < 0.05 comparing treatment.

Rapamycin treatment normalized the high mitochondrial number in Acsl1T−/− hearts

Compared with controls, Acsl1T−/− hearts contained more mitochondria, as demonstrated by 30% higher mitochondrial DNA content (Fig. 4A), 18% larger mitochondrial area (Fig. 4B), and 54% greater mitochondrial number (Fig. 4C). Rapamycin treatment normalized each of these measures, strongly suggesting that mTORC1 activation had caused these changes. Although mTORC1 increases mitochondrial biogenesis (34), in the current study, the expression of the mitochondrial biogenesis genes Pgc1a and Erra was not altered by either genotype or treatment (Fig. 4D), suggesting that the greater mitochondrial number in Acsl1T−/− hearts was not due to the formation of new mitochondria, but instead, to the inhibition of mitochondrial removal.

Figure 4.

Rapamycin treatment normalized high mitochondrial number in Acsl1T−/− hearts. Control and Acsl1T−/− mice were treated with vehicle or rapamycin daily for 2 wk. A) Mitochondrial DNA normalized to the nuclear gene H19 (n = 8). B) Number of mitochondria per cell area (n = 3). C) Mitochondrial area per cellular area (n = 3). Mitochondrial number and area were quantified using ImageJ software for at least 1000 mitochondria per heart (4–7 images). D) mRNA expression of genes controlling mitochondrial biogenesis (Pgc1a, Erra) (n = 4). Rapa, rapamycin; Veh, vehicle. *P < 0.05 comparing genotype. #P < 0.05 comparing treatment.

Inhibition of mTORC1 activated autophagy in Acsl1T−/− hearts

mTORC1 lowers the autophagic rate by inhibiting an early step in autophagosome formation (17). To determine whether the normalization of mitochondrial number and structure in Acsl1T−/− hearts by rapamycin treatment was due to increased clearance of damaged mitochondria, we examined the rates of autophagy in vehicle- and rapamycin-treated mice. Chloroquine raises the lysosomal pH, thereby inhibiting the degradation of the autophagolysosomes (35). Inactive microtubule-associated protein light chain 3B (LC3B-I), a protein found on the outer membrane of the autophagosome, is activated by cleavage and lipidation with phosphatidylethanolamine to form active microtubule-associated protein light chain 3B (LC3B-II), and then degraded within the autophagosome (36). Because chloroquine inhibits degradation without affecting autophagosome formation or the activation of LC3B-I, comparing the amount of activated LC3B-II in basal and chloroquine-treated hearts indicates how quickly the autophagosome is normally degraded (i.e., autophagic flux). In control hearts, chloroquine caused a 3-fold increase in the accumulation of activated LC3B-II relative to the inactive LC3B-I. The difference in these 2 ratios displays the rate of autophagy (35, 37). Although basal activation of LC3B appeared high in Acsl1T−/− hearts, treatment with chloroquine did not cause activated LC3B-II to increase, indicating that the autophagic flux was very low (Fig. 5A). Thus, the large amount of active LC3B-II in Acsl1T−/− hearts had probably resulted from impaired clearance of the autophagosome because of diminished long-term autophagic flux (35). When mice were treated with both rapamycin and chloroquine, more LC3B-II accumulated in both genotypes; however, the increase in heart LC3B-II in rapamycin- and chloroquine-treated Acsl1T−/− mice was 3 times greater than controls, indicating a very high rate of autophagy when mTORC1 was inhibited. This high rate of autophagic flux would compensate for the low clearance of damaged mitochondria and proteins in the basal state. The scaffolding protein p62 (SQSTM1) that binds to ubiquitin and LC3-II, is specifically degraded by autophagy, making it a useful marker for a low autophagic rate (38, 39). Accumulation of p62 in Acsl1T−/− hearts further confirmed impaired autophagy. Rapamycin treatment did not alter the amount of p62 in control hearts, but normalized p62 levels in Acsl1T−/− hearts (Fig. 5B), again confirming the mTORC1-mediated inhibition of autophagy. To determine whether mitochondria were specifically targeted for autophagy in Acsl1T−/− hearts, we examined the translocation of Parkin from cytosol to mitochondria. No genotype effect was found in vehicle-treated animals (Fig. 5C), indicating that targeted mitophagy had not increased despite the accumulation of damaged mitochondria. Two weeks of rapamycin treatment did not alter Parkin translocation in control animals, but lowered Parkin protein in both cytosol and mitochondria of Acsl1T−/− hearts (Fig. 5C), possibly to preserve mitochondrial number after damaged mitochondria had been cleared. Expression of Fis1, a mitochondrial fission protein, and Opa1, a mitochondrial fusion protein, was low in Acsl1T−/− but was normalized with rapamycin treatment (Fig. 5D), indicating that impaired fission and fusion may contribute to abnormal mitochondrial structure. Together with the normalization of mitochondrial number and structure, these data show that inhibiting mTORC1 in Acsl1T−/− hearts increased the autophagic rate and allowed damaged mitochondria to be cleared.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of mTORC1 activated autophagy in Acsl1T−/− hearts. A) Control and Acsl1T−/− mice were treated with vehicle or rapamycin for 14 d and vehicle or 60 mg/kg body weight chloroquine, a lysosome inhibitor, for the last 7 d (n = 4). Representative immunoblot of LC3B-I and LC3B-II (n = 4). B) p62 protein in ventricles from mice treated with vehicle or rapamycin for 2 wk (n = 4). C) Parkin localization, normalized to vehicle control (n = 3). D) Mitochondrial fission and fusion gene expression in ventricles from mice treated with vehicle or rapamycin for 2 wk (n = 4–8). Rapa, rapamycin. *P < 0.05 comparing genotype. #P < 0.05 comparing treatment.

Rapamycin treatment partially normalized mitochondrial function in Acsl1T−/− hearts

To determine whether reducing mTORC1 activation and increasing autophagy would enable mitochondrial function to recover, we examined electron transport chain function in control and Acsl1T−/− cardiac mitochondria from vehicle- and rapamycin-treated mice. No genotype or treatment difference was found in basal mitochondrial respiration (Fig. 6A). When stimulated with ADP, Acsl1T−/− mitochondria consumed 35% less oxygen than controls, and this deficit was not improved by rapamycin treatment (Fig. 6B). In response to the mitochondrial uncoupler FCCP, vehicle-treated Acsl1T−/− mitochondria consumed 43% less oxygen than controls. Rapamycin treatment normalized FCCP-stimulated respiration in Acsl1T−/− mitochondria, indicating that the mitochondria had regained their capacity for maximal respiration. To determine whether the loss of ACSL1 interfered with ATP synthesis, we examined complex V in cardiac mitochondria by measuring the activity and protein amount of ATP synthase. The ATP hydrolysis activity of complex V was lower in both vehicle- and rapamycin-treated Acsl1T−/− mitochondria, without loss of total protein (Fig. 6C). Thus, decreased ATP synthase activity had diminished ADP-stimulated oxygen consumption in Acsl1T−/− hearts, independent of mTOR activation. However, because maximal respiration measured in the presence of FCCP was independent of ATP synthase and became normal in rapamycin-treated Acsl1T−/− mitochondria, it appears that short-term rapamycin treatment partially normalized mitochondrial function.

Figure 6.

Rapamycin treatment partially normalized mitochondrial function in Acsl1T−/− hearts. Control and Acsl1T−/− mice were treated with vehicle or rapamycin daily for 2 wk. A and B) Mitochondrial function was measured in isolated mitochondria using a Seahorse XF24 Analyzer, which sequentially injected ADP, oligomycin, FCCP, and antimycin A (n = 4–5). C) Mitochondrial complexes were separated by native electrophoresis and stained for either complex V (ATP synthase) activity or total complex V (n = 4). OCR, O2 consumption rate; Rapa, rapamycin. *P < 0.05 comparing genotype. #P < 0.05 comparing treatment.

DISCUSSION

The loss of ACSL1 in highly oxidative tissues such as heart causes a severe deficit in fatty acid oxidation and a marked increase in glucose use. It has been questioned whether the substrate used by the heart for ATP production is important for heart health. An acute increase in workload causes the heart to preferentially increase carbohydrate metabolism (40), and the failing heart exhibits a low rate of fatty acid oxidation and a high glycolytic rate (8, 41, 42). An increase in glucose use becomes important for ATP production in the absence of oxygen or with inadequate mitochondrial energy provision. During pressure overload, for example, the overexpression of the glucose transporter 1 prevents the loss of mitochondrial function, presumably due to increased glucose use (43). Similarly, cardiac deficiency of malonyl-CoA decarboxylase impairs fatty acid oxidation, enhances glycolysis and glucose oxidation, and protects hearts during ischemia–reperfusion (44). Although acute changes in metabolism may protect the heart from injury, the question remains as to whether chronic glucose use itself is detrimental. When glucose transporter 1-overexpressing mice are fed a high-fat diet, their hearts exhibit oxidative stress and loss of contractile force (45). Reducing fatty acid oxidation can also be harmful if large amounts of unoxidized lipotoxic lipids accumulate, as occurs in hearts deficient in carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1b that fail in response to pressure overload (32). Thus, the lack of fatty acid uptake in Acsl1T−/− hearts, as evidenced by low uptake of 2-Br-[14C]palmitate, may have protected the hearts from further dysfunction by limiting lipid accumulation.

mTORC1 is activated by signals of high nutrient availability and is inhibited by signals of low energy status like activated AMPK (46). In Acsl1T−/− hearts, however, the enhanced glucose use effectively compensates for the lack of fatty acid oxidation. Glucose compensation apparently provides a signal of nutritional excess, because both diminished phospho-AMPK and activated mTORC1 are observed in other similar heart models (47). In isolated, perfused working hearts, mTOR is activated when the rate of glucose uptake exceeds oxidation and causes glucose-6-phosphate to accumulate (10). The metabolism of glucose to glucose-6-phosphate is also required for insulin-mediated activation of mTORC1 (11), suggesting a mechanism by which cells sense the amount of available glucose. Because Acsl1T−/− hearts take up 8-fold more 2-deoxyglucose and contain 3 times more glucose-6-phosphate than controls (9), the switch to a high rate of glucose metabolism may underlie mTORC1 activation. Rapamycin treatment does not modify fatty acid or glucose metabolism in hearts lacking ACSL1 (12), indicating that altered substrate metabolism did not contribute to rapamycin-induced normalization of mitochondrial structure and maximal respiration.

In the heart, mTORC1 activation is required for growth; both global and cardiac-specific knockouts of mTOR are embryonic lethal (14, 48). A temporal knockout of mTOR in adult heart demonstrated that mTOR is also needed for normal mitochondrial function, fatty acid oxidation, and heart contraction (16). However, the consequences of chronic mTORC1 hyperactivation in adult heart are less well understood. Overexpressing wild-type mTOR (49, 50) or constitutively active mTOR (51) in the heart activates mTORC1 signaling pathways but does not stimulate heart enlargement, suggesting that the development of hypertrophy requires an additional factor such as excess energy availability or pressure overload (52, 53). Because prolonged pressure overload itself leads to heart failure and impaired mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (54), we asked whether chronic mTORC1 activation in the absence of pressure overload would alter mitochondrial structure and function.

Treatment of Acsl1T−/− mice with rapamycin normalized mTORC1 signaling and heart size and relieved the block on autophagy. Autophagy is critical for the turnover of damaged organelles, proteins, and lipid droplets in nonadipose tissues. This quality control process is indispensable in the heart, as impaired autophagy can trigger cell death during ischemia (55, 56), cause a cardiomyopathy (57, 58), and exacerbate overload-induced heart failure (59). Conversely, autophagy protects cardiomyocytes from mitochondrial stress induced by antimycin A treatment (60). The high rate of autophagy that occurred after treating Acsl1T−/− mice with rapamycin suggests that chronically activated mTORC1 had inhibited autophagy. Although treating H9c2 cardiomyocytes with 500 µM palmitate and high-fat diet feeding can induce autophagy (61), excess fatty acids are not present in the Acsl1T−/− hearts (9). When mTORC1 activity was reduced in Acsl1T−/− hearts for 1 wk, large numbers of autophagic vacuoles were observed. After 2 wk of rapamycin treatment, the number of mitochondria had decreased to that of control animals, fewer abnormal mitochondria were observed, and the maximal respiration rate was normalized, indicating that the high rate of autophagy that occurred after rapamycin treatment had cleared the damaged mitochondria.

Although mTORC1 inhibition normalized maximal respiration in Acsl1T−/− mitochondria, the improved clearance of damaged mitochondria did not improve ADP-stimulated respiration. This impairment was likely due to the deficiency in ATP synthase activity, which produces ∼95% of cellular ATP (62). The proteins of the ATP synthase complex undergo numerous posttranslational modifications that can be altered by energy status or oxidative stress; these modifications can affect both the formation and activity of the complex (63–66). One recent example is the inhibition of ATP synthase by acetylation in the absence of the mitochondrial deacetylase sirtuin 3, which is activated by NAD+ (64), showing that alterations in redox status can influence ATP synthase activity. Despite the low ATP synthase activity in Acsl1T−/− hearts, activated AMPK is lower than in controls and ATP content is normal (9), indicating sufficient ATP production. In addition to the complete oxidation of glucose, Acsl1T−/− hearts may also partially offset the fuel deficit through both enhanced glycolysis and by an increased oxidation of amino acids.

In Acsl1T−/− hearts, high glucose use was associated with chronically activated mTORC1. The resulting inhibition of autophagy altered mitochondrial structure and diminished maximal respiration capacity, but not contractile function. Low ATP synthase activity coupled with impaired maximal respiration suggests that Acsl1T−/− hearts may have used glycolysis to augment ATP production. Surprisingly, the defect in cardiac respiratory function does not diminish longevity or systolic function in unstressed Acsl1T−/− mice (9). Under the stress of pressure overload, however, excessive reliance on glucose may harm systolic function. It will be of interest to determine if inhibiting mTORC1 can improve the response to these stresses in Acsl1T−/− hearts.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants DK59935 (to R.A.C.) and the University of North Carolina Nutrition Obesity Research Center DK056350, NIH Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Predoctoral Training Grants T32HL069768 (to T.J.G.) and T32-HL069768 (to J.M.E.), predoctoral fellowships 13PRE16910109 (to T.J.G.) and 0815054E (to J.M.E.), and 12GRNT12030144 from the American Heart Association Mid-Atlantic Division (to R.A.C.). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- ACSL

acyl-CoA synthetase

- ACSL1

long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase isoform 1

- FCCP

carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy)-phenylhydrazone

- LC3B

microtubule-associated protein light chain 3B

- LC3B-I

inactive microtubule-associated protein light chain 3B

- LC3B-II

active microtubule-associated protein light chain 3B

- mTOR

mechanistic target of rapamycin

- mTORC1

mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1

- p62/SQSTM1

sequestome 1

- TAG

triacylglycerol

REFERENCES

- 1.Duncan J. G., Bharadwaj K. G., Fong J. L., Mitra R., Sambandam N., Courtois M. R., Lavine K. J., Goldberg I. J., Kelly D. P. (2010) Rescue of cardiomyopathy in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha transgenic mice by deletion of lipoprotein lipase identifies sources of cardiac lipids and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha activators. Circulation 121, 426–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doenst T., Nguyen T. D., Abel E. D. (2013) Cardiac metabolism in heart failure: implications beyond ATP production. Circ. Res. 113, 709–724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belke D. D., Larsen T. S., Gibbs E. M., Severson D. L. (2000) Altered metabolism causes cardiac dysfunction in perfused hearts from diabetic (db/db) mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 279, E1104–E1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazumder P. K., O’Neill B. T., Roberts M. W., Buchanan J., Yun U. J., Cooksey R. C., Boudina S., Abel E. D. (2004) Impaired cardiac efficiency and increased fatty acid oxidation in insulin-resistant ob/ob mouse hearts. Diabetes 53, 2366–2374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allard M. F., Henning S. L., Wambolt R. B., Granleese S. R., English D. R., Lopaschuk G. D. (1997) Glycogen metabolism in the aerobic hypertrophied rat heart. Circulation 96, 676–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barger P. M., Kelly D. P. (1999) Fatty acid utilization in the hypertrophied and failing heart: molecular regulatory mechanisms. Am. J. Med. Sci. 318, 36–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tian R. (2003) Transcriptional regulation of energy substrate metabolism in normal and hypertrophied heart. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 5, 454–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dávila-Román V. G., Vedala G., Herrero P., de las Fuentes L., Rogers J. G., Kelly D. P., Gropler R. J. (2002) Altered myocardial fatty acid and glucose metabolism in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 40, 271–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellis J. M., Mentock S. M., Depetrillo M. A., Koves T. R., Sen S., Watkins S. M., Muoio D. M., Cline G. W., Taegtmeyer H., Shulman G. I., Willis M. S., Coleman R. A. (2011) Mouse cardiac acyl coenzyme a synthetase 1 deficiency impairs fatty acid oxidation and induces cardiac hypertrophy. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 1252–1262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sen S., Kundu B. K., Wu H. C., Hashmi S. S., Guthrie P., Locke L. W., Roy R. J., Matherne G. P., Berr S. S., Terwelp M., Scott B., Carranza S., Frazier O. H., Glover D. K., Dillmann W. H., Gambello M. J., Entman M. L., Taegtmeyer H. (2013) Glucose regulation of load-induced mTOR signaling and ER stress in mammalian heart. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2, e004796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma S., Guthrie P. H., Chan S. S., Haq S., Taegtmeyer H. (2007) Glucose phosphorylation is required for insulin-dependent mTOR signalling in the heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 76, 71–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paul D. S., Grevengoed T. J., Pascual F., Ellis J. M., Willis M. S., Coleman R. A. (2014) Deficiency of cardiac Acyl-CoA synthetase-1 induces diastolic dysfunction, but pathologic hypertrophy is reversed by rapamycin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1841, 880–887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang D., Contu R., Latronico M. V., Zhang J., Rizzi R., Catalucci D., Miyamoto S., Huang K., Ceci M., Gu Y., Dalton N. D., Peterson K. L., Guan K. L., Brown J. H., Chen J., Sonenberg N., Condorelli G. (2010) MTORC1 regulates cardiac function and myocyte survival through 4E-BP1 inhibition in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 2805–2816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu Y., Pires K. M., Whitehead K. J., Olsen C. D., Wayment B., Zhang Y. C., Bugger H., Ilkun O., Litwin S. E., Thomas G., Kozma S. C., Abel E. D. (2013) Mechanistic target of rapamycin (Mtor) is essential for murine embryonic heart development and growth. PLoS One 8, e54221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown N. F., Stefanovic-Racic M., Sipula I. J., Perdomo G. (2007) The mammalian target of rapamycin regulates lipid metabolism in primary cultures of rat hepatocytes. Metabolism 56, 1500–1507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu Y., Soto J., Anderson B., Riehle C., Zhang Y. C., Wende A. R., Jones D., McClain D. A., Abel E. D. (2013) Regulation of fatty acid metabolism by mTOR in adult murine hearts occurs independently of changes in PGC-1α. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 305, H41–H51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jung C. H., Jun C. B., Ro S. H., Kim Y. M., Otto N. M., Cao J., Kundu M., Kim D. H. (2009) ULK-Atg13-FIP200 complexes mediate mTOR signaling to the autophagy machinery. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 1992–2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu J. J., Liu J., Chen E. B., Wang J. J., Cao L., Narayan N., Fergusson M. M., Rovira I. I., Allen M., Springer D. A., Lago C. U., Zhang S., DuBois W., Ward T., deCabo R., Gavrilova O., Mock B., Finkel T. (2013) Increased mammalian lifespan and a segmental and tissue-specific slowing of aging after genetic reduction of mTOR expression. Cell Reports 4, 913–920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morita M., Gravel S. P., Chénard V., Sikström K., Zheng L., Alain T., Gandin V., Avizonis D., Arguello M., Zakaria C., McLaughlan S., Nouet Y., Pause A., Pollak M., Gottlieb E., Larsson O., St-Pierre J., Topisirovic I., Sonenberg N. (2013) mTORC1 controls mitochondrial activity and biogenesis through 4E-BP-dependent translational regulation. Cell Metab. 18, 698–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goo C. K., Lim H. Y., Ho Q. S., Too H. P., Clement M. V., Wong K. P. (2012) PTEN/Akt signaling controls mitochondrial respiratory capacity through 4E-BP1. PLoS One 7, e45806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schieke S. M., Phillips D., McCoy J. P. Jr., Aponte A. M., Shen R. F., Balaban R. S., Finkel T. (2006) The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway regulates mitochondrial oxygen consumption and oxidative capacity. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 27643–27652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aschenbrenner B., Druyan R., Albin R., Rabinowitz M. (1970) Haem a, cytochrome c and total protein turnover in mitochondria from rat heart and liver. Biochem. J. 119, 157–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gross N. J., Getz G. S., Rabinowitz M. (1969) Apparent turnover of mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid and mitochondrial phospholipids in the tissues of the rat. J. Biol. Chem. 244, 1552–1562 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoshino A., Matoba S., Iwai-Kanai E., Nakamura H., Kimata M., Nakaoka M., Katamura M., Okawa Y., Ariyoshi M., Mita Y., Ikeda K., Ueyama T., Okigaki M., Matsubara H. (2012) p53-TIGAR axis attenuates mitophagy to exacerbate cardiac damage after ischemia. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 52, 175–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kubli D. A., Zhang X., Lee Y., Hanna R. A., Quinsay M. N., Nguyen C. K., Jimenez R., Petrosyan S., Murphy A. N., Gustafsson A. B. (2013) Parkin protein deficiency exacerbates cardiac injury and reduces survival following myocardial infarction. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 915–926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas R. L., Roberts D. J., Kubli D. A., Lee Y., Quinsay M. N., Owens J. B., Fischer K. M., Sussman M. A., Miyamoto S., Gustafsson A. B. (2013) Loss of MCL-1 leads to impaired autophagy and rapid development of heart failure. Genes Dev. 27, 1365–1377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oka T., Hikoso S., Yamaguchi O., Taneike M., Takeda T., Tamai T., Oyabu J., Murakawa T., Nakayama H., Nishida K., Akira S., Yamamoto A., Komuro I., Otsu K. (2012) Mitochondrial DNA that escapes from autophagy causes inflammation and heart failure. Nature 485, 251–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamming D. W., Ye L., Katajisto P., Goncalves M. D., Saitoh M., Stevens D. M., Davis J. G., Salmon A. B., Richardson A., Ahima R. S., Guertin D. A., Sabatini D. M., Baur J. A. (2012) Rapamycin-induced insulin resistance is mediated by mTORC2 loss and uncoupled from longevity. Science 335, 1638–1643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barlow A. D., Nicholson M. L., Herbert T. P. (2013) Evidence for rapamycin toxicity in pancreatic β-cells and a review of the underlying molecular mechanisms. Diabetes 62, 2674–2682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Willis M. S., Homeister J. W., Rosson G. B., Annayev Y., Holley D., Holly S. P., Madden V. J., Godfrey V., Parise L. V., Bultman S. J. (2012) Functional redundancy of SWI/SNF catalytic subunits in maintaining vascular endothelial cells in the adult heart. Circ. Res. 111, e111–e122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wittig I., Karas M., Schägger H. (2007) High resolution clear native electrophoresis for in-gel functional assays and fluorescence studies of membrane protein complexes. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6, 1215–1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He L., Kim T., Long Q., Liu J., Wang P., Zhou Y., Ding Y., Prasain J., Wood P. A., Yang Q. (2012) Carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1b deficiency aggravates pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy caused by lipotoxicity. Circulation 126, 1705–1716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Füllekrug J., Ehehalt R., Poppelreuther M. (2012) Outlook: membrane junctions enable the metabolic trapping of fatty acids by intracellular acyl-CoA synthetases. Front. Physiol. 3, 401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cunningham J. T., Rodgers J. T., Arlow D. H., Vazquez F., Mootha V. K., Puigserver P. (2007) mTOR controls mitochondrial oxidative function through a YY1-PGC-1alpha transcriptional complex. Nature 450, 736–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mizushima N., Yoshimori T., Levine B. (2010) Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell 140, 313–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarkar S., Ravikumar B., Rubinsztein D. C. (2009) Autophagic clearance of aggregate-prone proteins associated with neurodegeneration. Methods Enzymol. 453, 83–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klionsky D. J., Abdalla F. C., Abeliovich H., Abraham R. T., Acevedo-Arozena A., Adeli K., Agholme L., Agnello M., Agostinis P., Aguirre-Ghiso J. A., Ahn H. J., Ait-Mohamed O., Ait-Si-Ali S., Akematsu T., Akira S., Al-Younes H. M., Al-Zeer M. A., Albert M. L., Albin R. L., Alegre-Abarrategui J., Aleo M. F., Alirezaei M., Almasan A., Almonte-Becerril M., Amano A., Amaravadi R., Amarnath S., Amer A. O., Andrieu-Abadie N., Anantharam V., Ann D. K., Anoopkumar-Dukie S., Aoki H., Apostolova N., Arancia G., Aris J. P., Asanuma K., Asare N. Y., Ashida H., Askanas V., Askew D. S., Auberger P., Baba M., Backues S. K., Baehrecke E. H., Bahr B. A., Bai X. Y., Bailly Y., Baiocchi R., Baldini G., Balduini W., Ballabio A., Bamber B. A., Bampton E. T., Bánhegyi G., Bartholomew C. R., Bassham D. C., Bast R. C. Jr., Batoko H., Bay B. H., Beau I., Béchet D. M., Begley T. J., Behl C., Behrends C., Bekri S., Bellaire B., Bendall L. J., Benetti L., Berliocchi L., Bernardi H., Bernassola F., Besteiro S., Bhatia-Kissova I., Bi X., Biard-Piechaczyk M., Blum J. S., Boise L. H., Bonaldo P., Boone D. L., Bornhauser B. C., Bortoluci K. R., Bossis I., Bost F., Bourquin J. P., Boya P., Boyer-Guittaut M., Bozhkov P. V., Brady N. R., Brancolini C., Brech A., Brenman J. E., Brennand A., Bresnick E. H., Brest P., Bridges D., Bristol M. L., Brookes P. S., Brown E. J., Brumell J. H., Brunetti-Pierri N., Brunk U. T., Bulman D. E., Bultman S. J., Bultynck G., Burbulla L. F., Bursch W., Butchar J. P., Buzgariu W., Bydlowski S. P., Cadwell K., Cahová M., Cai D., Cai J., Cai Q., Calabretta B., Calvo-Garrido J., Camougrand N., Campanella M., Campos-Salinas J., Candi E., Cao L., Caplan A. B., Carding S. R., Cardoso S. M., Carew J. S., Carlin C. R., Carmignac V., Carneiro L. A., Carra S., Caruso R. A., Casari G., Casas C., Castino R., Cebollero E., Cecconi F., Celli J., Chaachouay H., Chae H. J., Chai C. Y., Chan D. C., Chan E. Y., Chang R. C., Che C. M., Chen C. C., Chen G. C., Chen G. Q., Chen M., Chen Q., Chen S. S., Chen W., Chen X., Chen X., Chen X., Chen Y. G., Chen Y., Chen Y., Chen Y. J., Chen Z., Cheng A., Cheng C. H., Cheng Y., Cheong H., Cheong J. H., Cherry S., Chess-Williams R., Cheung Z. H., Chevet E., Chiang H. L., Chiarelli R., Chiba T., Chin L. S., Chiou S. H., Chisari F. V., Cho C. H., Cho D. H., Choi A. M., Choi D., Choi K. S., Choi M. E., Chouaib S., Choubey D., Choubey V., Chu C. T., Chuang T. H., Chueh S. H., Chun T., Chwae Y. J., Chye M. L., Ciarcia R., Ciriolo M. R., Clague M. J., Clark R. S., Clarke P. G., Clarke R., Codogno P., Coller H. A., Colombo M. I., Comincini S., Condello M., Condorelli F., Cookson M. R., Coombs G. H., Coppens I., Corbalan R., Cossart P., Costelli P., Costes S., Coto-Montes A., Couve E., Coxon F. P., Cregg J. M., Crespo J. L., Cronjé M. J., Cuervo A. M., Cullen J. J., Czaja M. J., D’Amelio M., Darfeuille-Michaud A., Davids L. M., Davies F. E., De Felici M., de Groot J. F., de Haan C. A., De Martino L., De Milito A., De Tata V., Debnath J., Degterev A., Dehay B., Delbridge L. M., Demarchi F., Deng Y. Z., Dengjel J., Dent P., Denton D., Deretic V., Desai S. D., Devenish R. J., Di Gioacchino M., Di Paolo G., Di Pietro C., Díaz-Araya G., Díaz-Laviada I., Diaz-Meco M. T., Diaz-Nido J., Dikic I., Dinesh-Kumar S. P., Ding W. X., Distelhorst C. W., Diwan A., Djavaheri-Mergny M., Dokudovskaya S., Dong Z., Dorsey F. C., Dosenko V., Dowling J. J., Doxsey S., Dreux M., Drew M. E., Duan Q., Duchosal M. A., Duff K., Dugail I., Durbeej M., Duszenko M., Edelstein C. L., Edinger A. L., Egea G., Eichinger L., Eissa N. T., Ekmekcioglu S., El-Deiry W. S., Elazar Z., Elgendy M., Ellerby L. M., Eng K. E., Engelbrecht A. M., Engelender S., Erenpreisa J., Escalante R., Esclatine A., Eskelinen E. L., Espert L., Espina V., Fan H., Fan J., Fan Q. W., Fan Z., Fang S., Fang Y., Fanto M., Fanzani A., Farkas T., Farré J. C., Faure M., Fechheimer M., Feng C. G., Feng J., Feng Q., Feng Y., Fésüs L., Feuer R., Figueiredo-Pereira M. E., Fimia G. M., Fingar D. C., Finkbeiner S., Finkel T., Finley K. D., Fiorito F., Fisher E. A., Fisher P. B., Flajolet M., Florez-McClure M. L., Florio S., Fon E. A., Fornai F., Fortunato F., Fotedar R., Fowler D. H., Fox H. S., Franco R., Frankel L. B., Fransen M., Fuentes J. M., Fueyo J., Fujii J., Fujisaki K., Fujita E., Fukuda M., Furukawa R. H., Gaestel M., Gailly P., Gajewska M., Galliot B., Galy V., Ganesh S., Ganetzky B., Ganley I. G., Gao F. B., Gao G. F., Gao J., Garcia L., Garcia-Manero G., Garcia-Marcos M., Garmyn M., Gartel A. L., Gatti E., Gautel M., Gawriluk T. R., Gegg M. E., Geng J., Germain M., Gestwicki J. E., Gewirtz D. A., Ghavami S., Ghosh P., Giammarioli A. M., Giatromanolaki A. N., Gibson S. B., Gilkerson R. W., Ginger M. L., Ginsberg H. N., Golab J., Goligorsky M. S., Golstein P., Gomez-Manzano C., Goncu E., Gongora C., Gonzalez C. D., Gonzalez R., González-Estévez C., González-Polo R. A., Gonzalez-Rey E., Gorbunov N. V., Gorski S., Goruppi S., Gottlieb R. A., Gozuacik D., Granato G. E., Grant G. D., Green K. N., Gregorc A., Gros F., Grose C., Grunt T. W., Gual P., Guan J. L., Guan K. L., Guichard S. M., Gukovskaya A. S., Gukovsky I., Gunst J., Gustafsson A. B., Halayko A. J., Hale A. N., Halonen S. K., Hamasaki M., Han F., Han T., Hancock M. K., Hansen M., Harada H., Harada M., Hardt S. E., Harper J. W., Harris A. L., Harris J., Harris S. D., Hashimoto M., Haspel J. A., Hayashi S., Hazelhurst L. A., He C., He Y. W., Hébert M. J., Heidenreich K. A., Helfrich M. H., Helgason G. V., Henske E. P., Herman B., Herman P. K., Hetz C., Hilfiker S., Hill J. A., Hocking L. J., Hofman P., Hofmann T. G., Höhfeld J., Holyoake T. L., Hong M. H., Hood D. A., Hotamisligil G. S., Houwerzijl E. J., Høyer-Hansen M., Hu B., Hu C. A., Hu H. M., Hua Y., Huang C., Huang J., Huang S., Huang W. P., Huber T. B., Huh W. K., Hung T. H., Hupp T. R., Hur G. M., Hurley J. B., Hussain S. N., Hussey P. J., Hwang J. J., Hwang S., Ichihara A., Ilkhanizadeh S., Inoki K., Into T., Iovane V., Iovanna J. L., Ip N. Y., Isaka Y., Ishida H., Isidoro C., Isobe K., Iwasaki A., Izquierdo M., Izumi Y., Jaakkola P. M., Jäättelä M., Jackson G. R., Jackson W. T., Janji B., Jendrach M., Jeon J. H., Jeung E. B., Jiang H., Jiang H., Jiang J. X., Jiang M., Jiang Q., Jiang X., Jiang X., Jiménez A., Jin M., Jin S., Joe C. O., Johansen T., Johnson D. E., Johnson G. V., Jones N. L., Joseph B., Joseph S. K., Joubert A. M., Juhász G., Juillerat-Jeanneret L., Jung C. H., Jung Y. K., Kaarniranta K., Kaasik A., Kabuta T., Kadowaki M., Kagedal K., Kamada Y., Kaminskyy V. O., Kampinga H. H., Kanamori H., Kang C., Kang K. B., Kang K. I., Kang R., Kang Y. A., Kanki T., Kanneganti T. D., Kanno H., Kanthasamy A. G., Kanthasamy A., Karantza V., Kaushal G. P., Kaushik S., Kawazoe Y., Ke P. Y., Kehrl J. H., Kelekar A., Kerkhoff C., Kessel D. H., Khalil H., Kiel J. A., Kiger A. A., Kihara A., Kim D. R., Kim D. H., Kim D. H., Kim E. K., Kim H. R., Kim J. S., Kim J. H., Kim J. C., Kim J. K., Kim P. K., Kim S. W., Kim Y. S., Kim Y., Kimchi A., Kimmelman A. C., King J. S., Kinsella T. J., Kirkin V., Kirshenbaum L. A., Kitamoto K., Kitazato K., Klein L., Klimecki W. T., Klucken J., Knecht E., Ko B. C., Koch J. C., Koga H., Koh J. Y., Koh Y. H., Koike M., Komatsu M., Kominami E., Kong H. J., Kong W. J., Korolchuk V. I., Kotake Y., Koukourakis M. I., Kouri Flores J. B., Kovács A. L., Kraft C., Krainc D., Krämer H., Kretz-Remy C., Krichevsky A. M., Kroemer G., Krüger R., Krut O., Ktistakis N. T., Kuan C. Y., Kucharczyk R., Kumar A., Kumar R., Kumar S., Kundu M., Kung H. J., Kurz T., Kwon H. J., La Spada A. R., Lafont F., Lamark T., Landry J., Lane J. D., Lapaquette P., Laporte J. F., László L., Lavandero S., Lavoie J. N., Layfield R., Lazo P. A., Le W., Le Cam L., Ledbetter D. J., Lee A. J., Lee B. W., Lee G. M., Lee J., Lee J. H., Lee M., Lee M. S., Lee S. H., Leeuwenburgh C., Legembre P., Legouis R., Lehmann M., Lei H. Y., Lei Q. Y., Leib D. A., Leiro J., Lemasters J. J., Lemoine A., Lesniak M. S., Lev D., Levenson V. V., Levine B., Levy E., Li F., Li J. L., Li L., Li S., Li W., Li X. J., Li Y. B., Li Y. P., Liang C., Liang Q., Liao Y. F., Liberski P. P., Lieberman A., Lim H. J., Lim K. L., Lim K., Lin C. F., Lin F. C., Lin J., Lin J. D., Lin K., Lin W. W., Lin W. C., Lin Y. L., Linden R., Lingor P., Lippincott-Schwartz J., Lisanti M. P., Liton P. B., Liu B., Liu C. F., Liu K., Liu L., Liu Q. A., Liu W., Liu Y. C., Liu Y., Lockshin R. A., Lok C. N., Lonial S., Loos B., Lopez-Berestein G., López-Otín C., Lossi L., Lotze M. T., Lőw P., Lu B., Lu B., Lu B., Lu Z., Luciano F., Lukacs N. W., Lund A. H., Lynch-Day M. A., Ma Y., Macian F., MacKeigan J. P., Macleod K. F., Madeo F., Maiuri L., Maiuri M. C., Malagoli D., Malicdan M. C., Malorni W., Man N., Mandelkow E. M., Manon S., Manov I., Mao K., Mao X., Mao Z., Marambaud P., Marazziti D., Marcel Y. L., Marchbank K., Marchetti P., Marciniak S. J., Marcondes M., Mardi M., Marfe G., Mariño G., Markaki M., Marten M. R., Martin S. J., Martinand-Mari C., Martinet W., Martinez-Vicente M., Masini M., Matarrese P., Matsuo S., Matteoni R., Mayer A., Mazure N. M., McConkey D. J., McConnell M. J., McDermott C., McDonald C., McInerney G. M., McKenna S. L., McLaughlin B., McLean P. J., McMaster C. R., McQuibban G. A., Meijer A. J., Meisler M. H., Meléndez A., Melia T. J., Melino G., Mena M. A., Menendez J. A., Menna-Barreto R. F., Menon M. B., Menzies F. M., Mercer C. A., Merighi A., Merry D. E., Meschini S., Meyer C. G., Meyer T. F., Miao C. Y., Miao J. Y., Michels P. A., Michiels C., Mijaljica D., Milojkovic A., Minucci S., Miracco C., Miranti C. K., Mitroulis I., Miyazawa K., Mizushima N., Mograbi B., Mohseni S., Molero X., Mollereau B., Mollinedo F., Momoi T., Monastyrska I., Monick M. M., Monteiro M. J., Moore M. N., Mora R., Moreau K., Moreira P. I., Moriyasu Y., Moscat J., Mostowy S., Mottram J. C., Motyl T., Moussa C. E., Müller S., Münger K., Münz C., Murphy L. O., Murphy M. E., Musarò A., Mysorekar I., Nagata E., Nagata K., Nahimana A., Nair U., Nakagawa T., Nakahira K., Nakano H., Nakatogawa H., Nanjundan M., Naqvi N. I., Narendra D. P., Narita M., Navarro M., Nawrocki S. T., Nazarko T. Y., Nemchenko A., Netea M. G., Neufeld T. P., Ney P. A., Nezis I. P., Nguyen H. P., Nie D., Nishino I., Nislow C., Nixon R. A., Noda T., Noegel A. A., Nogalska A., Noguchi S., Notterpek L., Novak I., Nozaki T., Nukina N., Nürnberger T., Nyfeler B., Obara K., Oberley T. D., Oddo S., Ogawa M., Ohashi T., Okamoto K., Oleinick N. L., Oliver F. J., Olsen L. J., Olsson S., Opota O., Osborne T. F., Ostrander G. K., Otsu K., Ou J. H., Ouimet M., Overholtzer M., Ozpolat B., Paganetti P., Pagnini U., Pallet N., Palmer G. E., Palumbo C., Pan T., Panaretakis T., Pandey U. B., Papackova Z., Papassideri I., Paris I., Park J., Park O. K., Parys J. B., Parzych K. R., Patschan S., Patterson C., Pattingre S., Pawelek J. M., Peng J., Perlmutter D. H., Perrotta I., Perry G., Pervaiz S., Peter M., Peters G. J., Petersen M., Petrovski G., Phang J. M., Piacentini M., Pierre P., Pierrefite-Carle V., Pierron G., Pinkas-Kramarski R., Piras A., Piri N., Platanias L. C., Pöggeler S., Poirot M., Poletti A., Poüs C., Pozuelo-Rubio M., Prætorius-Ibba M., Prasad A., Prescott M., Priault M., Produit-Zengaffinen N., Progulske-Fox A., Proikas-Cezanne T., Przedborski S., Przyklenk K., Puertollano R., Puyal J., Qian S. B., Qin L., Qin Z. H., Quaggin S. E., Raben N., Rabinowich H., Rabkin S. W., Rahman I., Rami A., Ramm G., Randall G., Randow F., Rao V. A., Rathmell J. C., Ravikumar B., Ray S. K., Reed B. H., Reed J. C., Reggiori F., Régnier-Vigouroux A., Reichert A. S., Reiners J. J. Jr., Reiter R. J., Ren J., Revuelta J. L., Rhodes C. J., Ritis K., Rizzo E., Robbins J., Roberge M., Roca H., Roccheri M. C., Rocchi S., Rodemann H. P., Rodríguez de Córdoba S., Rohrer B., Roninson I. B., Rosen K., Rost-Roszkowska M. M., Rouis M., Rouschop K. M., Rovetta F., Rubin B. P., Rubinsztein D. C., Ruckdeschel K., Rucker E. B. III, Rudich A., Rudolf E., Ruiz-Opazo N., Russo R., Rusten T. E., Ryan K. M., Ryter S. W., Sabatini D. M., Sadoshima J., Saha T., Saitoh T., Sakagami H., Sakai Y., Salekdeh G. H., Salomoni P., Salvaterra P. M., Salvesen G., Salvioli R., Sanchez A. M., Sánchez-Alcázar J. A., Sánchez-Prieto R., Sandri M., Sankar U., Sansanwal P., Santambrogio L., Saran S., Sarkar S., Sarwal M., Sasakawa C., Sasnauskiene A., Sass M., Sato K., Sato M., Schapira A. H., Scharl M., Schätzl H. M., Scheper W., Schiaffino S., Schneider C., Schneider M. E., Schneider-Stock R., Schoenlein P. V., Schorderet D. F., Schüller C., Schwartz G. K., Scorrano L., Sealy L., Seglen P. O., Segura-Aguilar J., Seiliez I., Seleverstov O., Sell C., Seo J. B., Separovic D., Setaluri V., Setoguchi T., Settembre C., Shacka J. J., Shanmugam M., Shapiro I. M., Shaulian E., Shaw R. J., Shelhamer J. H., Shen H. M., Shen W. C., Sheng Z. H., Shi Y., Shibuya K., Shidoji Y., Shieh J. J., Shih C. M., Shimada Y., Shimizu S., Shintani T., Shirihai O. S., Shore G. C., Sibirny A. A., Sidhu S. B., Sikorska B., Silva-Zacarin E. C., Simmons A., Simon A. K., Simon H. U., Simone C., Simonsen A., Sinclair D. A., Singh R., Sinha D., Sinicrope F. A., Sirko A., Siu P. M., Sivridis E., Skop V., Skulachev V. P., Slack R. S., Smaili S. S., Smith D. R., Soengas M. S., Soldati T., Song X., Sood A. K., Soong T. W., Sotgia F., Spector S. A., Spies C. D., Springer W., Srinivasula S. M., Stefanis L., Steffan J. S., Stendel R., Stenmark H., Stephanou A., Stern S. T., Sternberg C., Stork B., Strålfors P., Subauste C. S., Sui X., Sulzer D., Sun J., Sun S. Y., Sun Z. J., Sung J. J., Suzuki K., Suzuki T., Swanson M. S., Swanton C., Sweeney S. T., Sy L. K., Szabadkai G., Tabas I., Taegtmeyer H., Tafani M., Takács-Vellai K., Takano Y., Takegawa K., Takemura G., Takeshita F., Talbot N. J., Tan K. S., Tanaka K., Tanaka K., Tang D., Tang D., Tanida I., Tannous B. A., Tavernarakis N., Taylor G. S., Taylor G. A., Taylor J. P., Terada L. S., Terman A., Tettamanti G., Thevissen K., Thompson C. B., Thorburn A., Thumm M., Tian F., Tian Y., Tocchini-Valentini G., Tolkovsky A. M., Tomino Y., Tönges L., Tooze S. A., Tournier C., Tower J., Towns R., Trajkovic V., Travassos L. H., Tsai T. F., Tschan M. P., Tsubata T., Tsung A., Turk B., Turner L. S., Tyagi S. C., Uchiyama Y., Ueno T., Umekawa M., Umemiya-Shirafuji R., Unni V. K., Vaccaro M. I., Valente E. M., Van den Berghe G., van der Klei I. J., van Doorn W., van Dyk L. F., van Egmond M., van Grunsven L. A., Vandenabeele P., Vandenberghe W. P., Vanhorebeek I., Vaquero E. C., Velasco G., Vellai T., Vicencio J. M., Vierstra R. D., Vila M., Vindis C., Viola G., Viscomi M. T., Voitsekhovskaja O. V., von Haefen C., Votruba M., Wada K., Wade-Martins R., Walker C. L., Walsh C. M., Walter J., Wan X. B., Wang A., Wang C., Wang D., Wang F., Wang F., Wang G., Wang H., Wang H. G., Wang H. D., Wang J., Wang K., Wang M., Wang R. C., Wang X., Wang X., Wang Y. J., Wang Y., Wang Z., Wang Z. C., Wang Z., Wansink D. G., Ward D. M., Watada H., Waters S. L., Webster P., Wei L., Weihl C. C., Weiss W. A., Welford S. M., Wen L. P., Whitehouse C. A., Whitton J. L., Whitworth A. J., Wileman T., Wiley J. W., Wilkinson S., Willbold D., Williams R. L., Williamson P. R., Wouters B. G., Wu C., Wu D. C., Wu W. K., Wyttenbach A., Xavier R. J., Xi Z., Xia P., Xiao G., Xie Z., Xie Z., Xu D. Z., Xu J., Xu L., Xu X., Yamamoto A., Yamamoto A., Yamashina S., Yamashita M., Yan X., Yanagida M., Yang D. S., Yang E., Yang J. M., Yang S. Y., Yang W., Yang W. Y., Yang Z., Yao M. C., Yao T. P., Yeganeh B., Yen W. L., Yin J. J., Yin X. M., Yoo O. J., Yoon G., Yoon S. Y., Yorimitsu T., Yoshikawa Y., Yoshimori T., Yoshimoto K., You H. J., Youle R. J., Younes A., Yu L., Yu L., Yu S. W., Yu W. H., Yuan Z. M., Yue Z., Yun C. H., Yuzaki M., Zabirnyk O., Silva-Zacarin E., Zacks D., Zacksenhaus E., Zaffaroni N., Zakeri Z., Zeh H. J. III, Zeitlin S. O., Zhang H., Zhang H. L., Zhang J., Zhang J. P., Zhang L., Zhang L., Zhang M. Y., Zhang X. D., Zhao M., Zhao Y. F., Zhao Y., Zhao Z. J., Zheng X., Zhivotovsky B., Zhong Q., Zhou C. Z., Zhu C., Zhu W. G., Zhu X. F., Zhu X., Zhu Y., Zoladek T., Zong W. X., Zorzano A., Zschocke J., Zuckerbraun B. (2012) Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy 8, 445–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Komatsu M., Waguri S., Koike M., Sou Y. S., Ueno T., Hara T., Mizushima N., Iwata J., Ezaki J., Murata S., Hamazaki J., Nishito Y., Iemura S., Natsume T., Yanagawa T., Uwayama J., Warabi E., Yoshida H., Ishii T., Kobayashi A., Yamamoto M., Yue Z., Uchiyama Y., Kominami E., Tanaka K. (2007) Homeostatic levels of p62 control cytoplasmic inclusion body formation in autophagy-deficient mice. Cell 131, 1149–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pankiv S., Clausen T. H., Lamark T., Brech A., Bruun J. A., Outzen H., Øvervatn A., Bjørkøy G., Johansen T. (2007) p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 24131–24145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goodwin G. W., Taylor C. S., Taegtmeyer H. (1998) Regulation of energy metabolism of the heart during acute increase in heart work. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 29530–29539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osorio J. C., Stanley W. C., Linke A., Castellari M., Diep Q. N., Panchal A. R., Hintze T. H., Lopaschuk G. D., Recchia F. A. (2002) Impaired myocardial fatty acid oxidation and reduced protein expression of retinoid X receptor-alpha in pacing-induced heart failure. Circulation 106, 606–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bugger H., Schwarzer M., Chen D., Schrepper A., Amorim P. A., Schoepe M., Nguyen T. D., Mohr F. W., Khalimonchuk O., Weimer B. C., Doenst T. (2010) Proteomic remodelling of mitochondrial oxidative pathways in pressure overload-induced heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 85, 376–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pereira R. O., Wende A. R., Olsen C., Soto J., Rawlings T., Zhu Y., Anderson S. M., Abel E. D. (2013) Inducible overexpression of GLUT1 prevents mitochondrial dysfunction and attenuates structural remodeling in pressure overload but does not prevent left ventricular dysfunction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2, e000301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dyck J. R., Hopkins T. A., Bonnet S., Michelakis E. D., Young M. E., Watanabe M., Kawase Y., Jishage K., Lopaschuk G. D. (2006) Absence of malonyl coenzyme A decarboxylase in mice increases cardiac glucose oxidation and protects the heart from ischemic injury. Circulation 114, 1721–1728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yan J., Young M. E., Cui L., Lopaschuk G. D., Liao R., Tian R. (2009) Increased glucose uptake and oxidation in mouse hearts prevent high fatty acid oxidation but cause cardiac dysfunction in diet-induced obesity. Circulation 119, 2818–2828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laplante M., Sabatini D. M. (2012) mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell 149, 274–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sciarretta S., Volpe M., Sadoshima J. (2014) Mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in cardiac physiology and disease. Circ. Res. 114, 549–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murakami M., Ichisaka T., Maeda M., Oshiro N., Hara K., Edenhofer F., Kiyama H., Yonezawa K., Yamanaka S. (2004) mTOR is essential for growth and proliferation in early mouse embryos and embryonic stem cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 6710–6718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song X., Kusakari Y., Xiao C. Y., Kinsella S. D., Rosenberg M. A., Scherrer-Crosbie M., Hara K., Rosenzweig A., Matsui T. (2010) mTOR attenuates the inflammatory response in cardiomyocytes and prevents cardiac dysfunction in pathological hypertrophy. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 299, C1256–C1266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aoyagi T., Kusakari Y., Xiao C. Y., Inouye B. T., Takahashi M., Scherrer-Crosbie M., Rosenzweig A., Hara K., Matsui T. (2012) Cardiac mTOR protects the heart against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 303, H75–H85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shen W. H., Chen Z., Shi S., Chen H., Zhu W., Penner A., Bu G., Li W., Boyle D. W., Rubart M., Field L. J., Abraham R., Liechty E. A., Shou W. (2008) Cardiac restricted overexpression of kinase-dead mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) mutant impairs the mTOR-mediated signaling and cardiac function. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 13842–13849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McMullen J. R., Sherwood M. C., Tarnavski O., Zhang L., Dorfman A. L., Shioi T., Izumo S. (2004) Inhibition of mTOR signaling with rapamycin regresses established cardiac hypertrophy induced by pressure overload. Circulation 109, 3050–3055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shioi T., McMullen J. R., Tarnavski O., Converso K., Sherwood M. C., Manning W. J., Izumo S. (2003) Rapamycin attenuates load-induced cardiac hypertrophy in mice. Circulation 107, 1664–1670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schwarzer M., Schrepper A., Amorim P. A., Osterholt M., Doenst T. (2013) Pressure overload differentially affects respiratory capacity in interfibrillar and subsarcolemmal mitochondria. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 304, H529–H537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matsui Y., Takagi H., Qu X., Abdellatif M., Sakoda H., Asano T., Levine B., Sadoshima J. (2007) Distinct roles of autophagy in the heart during ischemia and reperfusion: roles of AMP-activated protein kinase and Beclin 1 in mediating autophagy. Circ. Res. 100, 914–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Das A., Salloum F. N., Durrant D., Ockaili R., Kukreja R. C. (2012) Rapamycin protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury through JAK2-STAT3 signaling pathway. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 53, 858–869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Choi J. C., Worman H. J. (2013) Reactivation of autophagy ameliorates LMNA cardiomyopathy. Autophagy 9, 110–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ramos F. J., Kaeberlein M., Kennedy B. K. (2013) Elevated MTORC1 signaling and impaired autophagy. Autophagy 9, 108–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu X., Hua Y., Nair S., Bucala R., Ren J. (2014) Macrophage migration inhibitory factor deletion exacerbates pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy through mitigating autophagy. Hypertension 63, 490–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dutta D., Xu J., Kim J. S., Dunn W. A. Jr., Leeuwenburgh C. (2013) Upregulated autophagy protects cardiomyocytes from oxidative stress-induced toxicity. Autophagy 9, 328–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jaishy B., Zhang Q., Chung H. S., Riehle C., Soto J., Jenkins S., Abel P., Cowart L. A., Van Eyk J. E., Abel E. D. (2015) Lipid-induced NOX2 activation inhibits autophagic flux by impairing lysosomal enzyme activity. J. Lipid Res. 56, 546–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kane L. A., Van Eyk J. E. (2009) Post-translational modifications of ATP synthase in the heart: biology and function. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 41, 145–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kane L. A., Youngman M. J., Jensen R. E., Van Eyk J. E. (2010) Phosphorylation of the F(1)F(o) ATP synthase beta subunit: functional and structural consequences assessed in a model system. Circ. Res. 106, 504–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vassilopoulos A., Pennington J. D., Andresson T., Rees D. M., Bosley A. D., Fearnley I. M., Ham A., Flynn C. R., Hill S., Rose K. L., Kim H. S., Deng C. X., Walker J. E., Gius D. (2014) SIRT3 deacetylates ATP synthase F1 complex proteins in response to nutrient- and exercise-induced stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 21, 551–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rahman M., Nirala N. K., Singh A., Zhu L. J., Taguchi K., Bamba T., Fukusaki E., Shaw L. M., Lambright D. G., Acharya J. K., Acharya U. R. (2014) Drosophila Sirt2/mammalian SIRT3 deacetylates ATP synthase β and regulates complex V activity. J. Cell Biol. 206, 289–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Taylor S. W., Fahy E., Murray J., Capaldi R. A., Ghosh S. S. (2003) Oxidative post-translational modification of tryptophan residues in cardiac mitochondrial proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 19587–19590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]