Abstract

Burkholderia sp. strain WSM4176 is an aerobic, motile, Gram-negative, non-spore-forming rod that was isolated from an effective N2-fixing root nodule of Lebeckia ambigua collected in Nieuwoudtville, Western Cape of South Africa, in October 2007. This plant persists in infertile, acidic and deep sandy soils, and is therefore an ideal candidate for a perennial based agriculture system in Western Australia. Here we describe the features of Burkholderia sp. strain WSM4176, which represents a potential inoculant quality strain for L. ambigua, together with sequence and annotation. The 9,065,247 bp high-quality-draft genome is arranged in 13 scaffolds of 65 contigs, contains 8369 protein-coding genes and 128 RNA-only encoding genes, and is part of the GEBA-RNB project proposal (Project ID 882).

Keywords: Root-nodule bacteria, Nitrogen fixation, Rhizobia, Betaproteobacteria, GEBA-RNB

Introduction

Leguminous pasture species are important in Western Australian agriculture because the soils are inherently infertile. Together with changing patterns of rainfall, this agricultural system cannot continue to rely on the current commercially used annual legumes. Deep-rooted herbaceous perennial legumes including Rhynchosia and Lebeckia species from the Cape Floristic Region in South Africa have been investigated because of their adaptation to acid and infertile soils [1–3]. These plants naturally occur in the CFR, which is one of the richest areas for plants in the world and covers 553,000 ha of land protected by the UNESCO as important world heritage. Elevations in this area range from 2077 m in the Groot Winterhoek to sea level in the De Hoop Nature Reserve. Moreover, a great part of the area is characterized by mountains, rivers, waterfalls and pools. In areas where Lebeckia ambigua is native, rainfall ranges between 150 and 400 mm annually. Parts of the CFR have thus similar soil and climate conditions to Western Australia.

In four expeditions to the Western Cape of South Africa, held between 2002 and 2007, nodules and seeds were collected and stored as previously described [4]. The isolation of bacteria from these nodules gave rise to a collection of 23 strains that were identified as Burkholderia. Unlike most of the previously studied rhizobial Burkholderia strains, this South African group appears to associate with papilionoid forage legumes, rather than Mimosa species. WSM4176 belongs to a subgroup of strains that were isolated in 2004 from Lebeckia ambigua nodules collected near Nieuwoudtville in the Western Cape of South Africa [3]. The site of collection was moderately grazed rangeland field owned by the Louw family, and the soil was composed of stony-sand with a pH of 6. Burkholderia sp. strain WSM4176 is highly effective at fixing nitrogen with Lebeckia ambigua, with which it forms crotaloid, indeterminate, nodules [3].

WSM4176 represents thus a potential inoculant quality strain for Lebeckia ambigua, which is being developed as a grazing legume adapted to infertile soils that receive 250–400 mm annual rainfall, where climate change has necessitated the domestication of agricultural species with altered characteristics. Therefore, this strain is of special interest to the IMG/GEBA project. Here we present a summary classification and a set of general features for Burkholderia sp. strain WSM4176 together with the description of the complete genome sequence and annotation.

Organism information

Classification and features

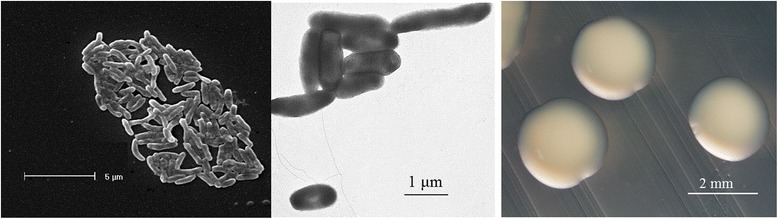

Burkholderia sp. strain WSM4176 is a motile, Gram-negative, non-spore-forming rod (Fig. 1 Left, Center) in the order Burkholderiales of the class Betaproteobacteria. The rod-shaped form varies in size with dimensions of 0.1–0.2 μm in width and 2.0–3.0 μm in length (Fig. 1 Left). It is fast growing, forming 0.5–1 mm diameter colonies after 24 h when grown on half Lupin Agar [5] and TY [6] at 28 °C. Colonies on ½LA are white-opaque, slightly domed, moderately mucoid with smooth margins (Fig. 1 Right).

Fig. 1.

Images of Burkholderia sp. strain WSM4176 using scanning (Left) and transmission (Center) electron microscopy and the appearance of colony morphology on solid media (Right)

Figure 2 shows the phylogenetic relationship of Burkholderia sp. strain WSM4176 in a 16S rRNA gene sequence based tree. This strain clusters closest to Burkholderia tuberum STM678T and Burkholderia phenoliruptrix AC1100T with 99.86 and 97.28 % sequence identity, respectively. Minimum Information about the Genome Sequence is provided in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of Burkholderia sp. strain WSM4176 (shown in blue print) relative to other type and non-type strains in the Burkholderia genus (1322 bp internal region). Cupriavidus taiwanensis LMG 19424T was used as outgroup. All sites were informative and there were no gap-containing sites. Phylogenetic analyses were performed using MEGA, version 5.05 [27]. The tree was build using the maximum likelihood method with the General Time Reversible model. Bootstrap analysis with 500 replicates was performed to assess the support of the clusters. Type strains are indicated with a superscript T. Strains with a genome sequencing project registered in GOLD [9] are in bold print and the GOLD ID is mentioned after the NCBI accession number. Published genomes are designated with an asterisk

Table 1.

Classification and general features of Burkholderia sp. strain WSM4176 in accordance with the MIGS recommendations [28] published by the Genome Standards Consortium [29]

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [30] | |

| Phylum Proteobacteria | TAS [31, 32] | ||

| Class Betaproteobacteria | TAS [33] | ||

| Order Burkholderiales | TAS [34] | ||

| Family Burkholderiaceae | TAS [35] | ||

| Genus Burkholderia | TAS [36] | ||

| Species Burkholderia sp. | TAS [3] | ||

| (Type) strain WSM4176 | TAS [3] | ||

| Gram stain | Negative | IDA [36] | |

| Cell shape | Rod | IDA | |

| Motility | Motile | IDA | |

| Sporulation | Non-sporulating | IDA [36] | |

| Temperature range | Not reported | ||

| Optimum temperature | 28 °C | IDA | |

| pH range; Optimum | Not reported | ||

| Carbon source | Not reported | ||

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Soil, root nodule on host | TAS [3] |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | Not reported | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | Aerobic | IDA |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Free living, symbiotic | TAS [3] |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | Non-pathogenic | NAS |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | South Africa | TAS [3] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection | 2007 | TAS [3] |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | −31.381 | TAS [3] |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | 19.30 | TAS [3] |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | 789 m | IDA |

Evidence codes – IDA inferred from direct assay, TAS traceable author statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature), NAS non-traceable author statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [37]

Symbiotaxonomy

Burkholderia sp. strain WSM4176 belongs to a group of Burkholderia strains that nodulate papilionoid forage legumes rather than the classical Burkholderia hosts Mimosa spp. (Mimosoideae) [7]. Burkholderia sp. strain WSM4176 was assessed for nodulation and nitrogen fixation on three separate L. ambigua genotypes (CRSLAM-37, CRSLAM-39 and CRSLAM-41) [3]. Strain WSM4176 could nodulate and fix effectively on CRSLAM-39 and CRSLAM-41 but was partially effective on CRSLAM-37 [3].

Genome sequencing information

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of its environmental and agricultural relevance to issues in global carbon cycling, alternative energy production, and biogeochemical importance, and is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea, The Root Nodulating Bacteria chapter project at the U.S. Department of Energy, Joint Genome Institute for projects of relevance to agency missions [8]. The genome project is deposited in the Genomes OnLine Database [9] and the high-quality permanent draft genome sequence in IMG [10]. Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by the JGI using state of the art sequencing technology [11]. A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Genome sequencing project information for Burkholderia sp. strain WSM4176

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | High-quality-permanent-draft |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Illumina CLIP PE and Illumina Std PE Unamplified |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | Illumina HiSeq 2000 |

| MIGS-31.2 | Fold coverage | 361 × Illumina |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | ALLPATHS V.r41554 |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling methods | Prodigal 1.4, GenePRIMP |

| Locus Tag | B014 | |

| Genbank ID | ARCY00000000 | |

| Genbank Date of Release | July 11, 2014 | |

| GOLD ID | Gi08873 | |

| BIOPROJECT | PRJNA169686 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source Material Identifier | WSM4176 |

| Project relevance | Symbiotic N2fixation, agriculture |

Growth conditions and genomic DNA preparation

Burkholderia sp. strain WSM4176 was grown to mid logarithmic phase in TY rich media [6] on a gyratory shaker at 28 °C. DNA was isolated from 60 mL of cells using a CTAB bacterial genomic DNA isolation method [12].

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome of Burkholderia sp. strain WSM4176 was sequenced at the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI) using Illumina data [13]. For this genome, we constructed and sequenced an Illumina short-insert paired-end library with an average insert size of 270 bp which generated 7,496,994 reads and an Illumina long-insert paired-end library with an average insert size of 6899.89 +/− 882.09 bp which generated 11,773,350 reads totaling 2891 Mbp of Illumina data (unpublished, Feng Chen). All general aspects of library construction and sequencing performed at the JGI can be found at the JGI’s web site [11]. The initial draft assembly contained 66 contigs in eight scaffold(s). The initial draft data was assembled with Allpaths, version r41554 [14], and the consensus was computationally shredded into 10 Kbp overlapping fake reads (shreds). The Illumina draft data was also assembled with Velvet, version 1.1.05 [15], and the consensus sequences were computationally shredded into 1.5 Kbp overlapping fake reads (shreds). The Illumina draft data was assembled again with Velvet using the shreds from the first Velvet assembly to guide the next assembly. The consensus from the second Velvet assembly was shredded into 1.5 Kbp overlapping fake reads. The fake reads from the Allpaths assembly and both Velvet assemblies and a subset of the Illumina CLIP paired-end reads were assembled using parallel phrap, version 4.24 (High Performance Software, LLC). Possible mis-assemblies were corrected with manual editing in Consed [16–18]. Gap closure was accomplished using repeat resolution software (Wei Gu, unpublished), and sequencing of bridging PCR fragments with Sanger and/or PacBio (unpublished, Cliff Han) technologies. For improved high quality draft and non-contiguous finished projects, one round of manual/wet lab finishing may have been completed. Primer walks, shatter libraries, and/or subsequent PCR reads may also be included for a finished project. A total of 11 PCR PacBio consensus sequences were completed to close gaps and to raise the quality of the final sequence. The total size of the genome is 9.1 Mb and the final assembly is based on 2891 Mbp of Illumina draft data, which provides an average 318× coverage of the genome.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using Prodigal [19] as part of the DOE-JGI Annotation pipeline [17], followed by a round of manual curation using the JGI GenePRIMP pipeline [20]. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information nonredundant database, UniProt, TIGRFam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. These data sources were combined to assert a product description for each predicted protein. Non-coding genes and miscellaneous features were predicted using tRNAscan-SE [21], RNAMMer [22], Rfam [23], TMHMM [24] and SignalP [23]. Additional gene prediction analyses and functional annotation were performed within the Integrated Microbial Genomes platform [24].

Genome properties

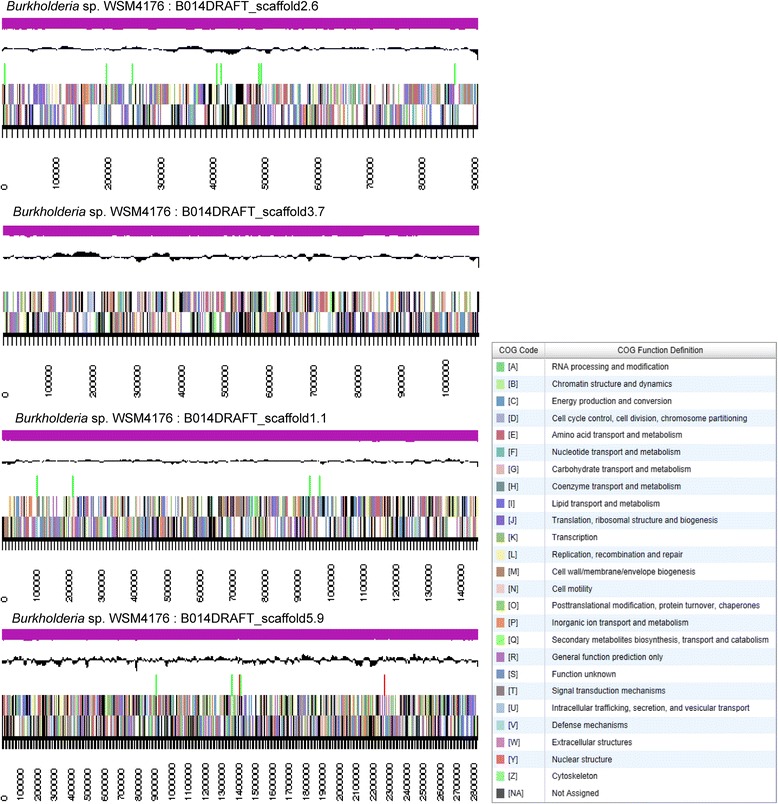

The genome is 9,065,247 nucleotides with 62.89 % GC content (Table 3) and comprised of 13 scaffolds and 65 contigs (Fig. 3). From a total of 8497 genes, 8369 were protein encoding and 128 RNA only encoding genes. The majority of genes (75.46 %) were assigned a putative function whilst the remaining genes were annotated as hypothetical. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3.

Genome statistics for Burkholderia sp. strain WSM4176

| Attribute | Value | % of total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 9,065,247 | 100.00 |

| DNA coding (bp) | 7,632,174 | 84.19 |

| DNA G+C (bp) | 5,701,432 | 62.89 |

| DNA scaffolds | 13 | |

| Total genes | 8497 | 100.00 |

| Protein-coding genes | 8369 | 98.49 |

| RNA genes | 128 | 1.51 |

| Pseudo genes | 0 | 0.00 |

| Genes in internal clusters | 648 | 7.63 |

| Genes with function prediction | 6412 | 75.46 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 5491 | 64.62 |

| Genes with Pfam domains | 6766 | 79.63 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 738 | 8.69 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 1865 | 21.95 |

| CRISPR repeats | 0 | 0.00 |

Fig. 3.

Graphical map of the genome of Burkholderia sp. strain WSM4176. First four large scaffolds are shown according to size. From the bottom to the top of each scaffold: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories as denoted by the IMG platform), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, sRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew

Table 4.

Number of protein coding genes of Burkholderia sp. strain WSM4176 associated with the general COG functional categories

| Code | Value | % age | COG category |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 200 | 3.21 | Translation |

| A | 1 | 0.02 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 596 | 9.55 | Transcription |

| L | 299 | 4.79 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 1 | 0.02 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 38 | 0.61 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis |

| V | 74 | 1.19 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 270 | 4.33 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 389 | 6.23 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 105 | 1.68 | Cell motility |

| U | 146 | 2.34 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 172 | 2.76 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 461 | 7.39 | Energy production conversion |

| G | 495 | 7.93 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 611 | 9.79 | Amino acid transport metabolism |

| F | 101 | 1.62 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 210 | 3.37 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 323 | 5.18 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 317 | 5.08 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 225 | 3.61 | Secondary metabolite biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 727 | 11.65 | General function prediction only |

| S | 479 | 7.68 | Function unknown |

| - | 3006 | 35.38 | Not in COGS |

The total is based on the total number of protein coding genes in the genome

Conclusion

Burkholderia sp. WSM4176 belongs to a group of Beta-rhizobia isolated from Lebeckia ambigua from the fynbos biome in South Africa [3]. WSM4176 is phylogeneticaly most closely related to Burkholderia tuberum STM678T. Both STM678T and WSM4176 have comparable genome sizes, 8.3–9.1 respectively. Recently, two more genomes from strains originating from Lebeckia ambigua were investigated, Burkholderia dilworthiiWSM3556T and Burkholderia sprentiaeWSM5005T [25]. Both of these strains have a genome size of 7.7 Mbp, which is considerably smaller than WSM4176. All four strains, STM678T, WSM3556T, WSM4176 and WSM5005T, contain a large number of genes assigned to transport and metabolism of amino acids (9.79–10.94 %) and carbohydrates (7.93–8.38 %), and transcription (9.55–9.94 %). Interestingly, STM678T was initially isolated from Aspalathus species but does not nodulate this host, however it has been shown to nodulate Cyclopia species from the same fynbos biome in South Africa as Lebeckia ambigua [26]. Considering the ability of these strains to nodulate and fix nitrogen effectively with legumes, they share in common many of the genes responsible for the nitrogenase pathway (IMG pathway number 798). The genome sequence of WSM4176 provides thus an unprecedented opportunity to study the host range and nitrogen fixation capacities of these fynbos bacteria.

Acknowledgements

This work was performed under the auspices of the US Department of Energy Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research Program, and by the University of California, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC52-07NA27344, and Los Alamos National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-06NA25396. We gratefully acknowledge the funding received from the Murdoch University Strategic Research Fund through the Crop and Plant Research Institute (CaPRI) and the Centre for Rhizobium Studies (CRS) at Murdoch University.

Abbreviations

- GEBA-RNB

Genomic encyclopedia of bacteria and archaea – root nodule bacteria

- JGI

Joint genome institute

- TY

Trypton yeast

- CTAB

Cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide

- WSM

Western Australian soil microbiology

- BNF

Biological nitrogen fixation

- CFR

Cape floristic region

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JH and RY supplied the strain and background information for this project, RT supplied DNA to JGI and performed all imaging, SDM and WR drafted the paper, JH provided financial support and all other authors were involved in sequencing the genome and editing the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Howieson JG, Yates RJ, Foster K, Real D, Besier B. Prospects for the future use of legumes. In: Dilworth MJ, James EK, Sprent JI, Newton WE, editors. Leguminous nitrogen-fixing symbioses. London: Elsevier; 2008. pp. 363–394. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garau G, Yates RJ, Deiana P, Howieson JG. Novel strains of nodulating Burkholderia have a role in nitrogen fixation with papilionoid herbaceous legumes adapted to acid, infertile soils. Soil Biol Biochem. 2009;41:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2008.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howieson JG, De Meyer SE, Vivas-Marfisi A, Ratnayake S, Ardley JK, Yates RJ. Novel Burkholderia bacteria isolated from Lebeckia ambigua - a perennial suffrutescent legume of the fynbos. Soil Biol Biochem. 2013;60:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yates RJ, Howieson JG, Nandasena KG, O’Hara GW. Root-nodule bacteria from indigenous legumes in the north-west of Western Australia and their interaction with exotic legumes. Soil Biol Biochem. 2004;36:1319–1329. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2004.04.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howieson JG, Ewing MA, D’antuono MF. Selection for acid tolerance in Rhizobium meliloti. Plant Soil. 1988;105:179–188. doi: 10.1007/BF02376781. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beringer JE. R factor transfer in Rhizobium leguminosarum. J Gen Microbiol. 1974;84:188–198. doi: 10.1099/00221287-84-1-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elliott GN, Chou J-H, Chen W-M, Bloemberg GV, Bontemps C, Martínez-Romero E, et al. Burkholderia spp. are the most competitive symbionts of Mimosa, particularly under N-limited conditions. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:762–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reeve W, Ardley J, Tian R, Eshraghi L, Yoon J, Ngamwisetkun P, et al. A genomic encyclopedia of the root nodule bacteria: assessing genetic diversity through a systematic biogeographic survey. Stand Genomic Sci. 2015;10:14. doi: 10.1186/1944-3277-10-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pagani I, Liolios K, Jansson J, Chen IM, Smirnova T, Nosrat B, Markowitz VM, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes OnLine Database (GOLD) v.4: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D571–579. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Markowitz VM, Chen I-MA, Palaniappan K, Chu K, Szeto E, Pillay M, et al. IMG 4 version of the integrated microbial genomes comparative analysis system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D560–D567. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.JGI Website. [http://www.jgi.doe.gov]

- 12.CTAB DNA extraction protocol. [http://jgi.doe.gov/collaborate-with-jgi/pmo-overview/protocols-sample-preparation-information/]

- 13.Mavromatis K, Land ML, Brettin TS, Quest DJ, Copeland A, Clum A, et al. The fast changing landscape of sequencing technologies and their impact on microbial genome assemblies and annotation. PLoS ONE. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gnerre S, MacCallum I, Przybylski D, Ribeiro FJ, Burton JN, Walker BJ, et al. High-quality draft assemblies of mammalian genomes from massively parallel sequence data. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1513–1518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017351108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zerbino D, Birney E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 2008;18:821–829. doi: 10.1101/gr.074492.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ewing B, Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. II. Error probabilities. Genome Res. 1998;8:186–194. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.3.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ewing B, Hillier L, Wendl MC, Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res. 1998;8:175–185. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.3.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon D, Abajian C, Green P. Consed: a graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome Res. 1998;8:195–202. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.3.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pati A, Ivanova NN, Mikhailova N, Ovchinnikova G, Hooper SD, Lykidis A, Kyrpides NC. GenePRIMP: a gene prediction improvement pipeline for prokaryotic genomes. Nat Methods. 2010;7:455–457. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.0955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:783–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markowitz VM, Mavromatis K, Ivanova NN, Chen IM, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2271–2278. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reeve W, De Meyer S, Terpolilli J, Melino V, Ardley J, Rui T, Tiwari R, et al. Genome sequence of the Lebeckia ambigua - nodulating Burkholderia sprentiae strain WSM5005T. Stand Genomic Sci. 2013;9:385–394. doi: 10.4056/sigs.4558268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elliott GN, Chen WM, Bontemps C, Chou JH, Young JPW, Sprent JI, James EK. Nodulation of Cyclopia spp. (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) by Burkholderia tuberum. Ann Bot. 2007;100:1403–1411. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, et al. Towards a richer description of our complete collection of genomes and metagenomes “Minimum Information about a Genome Sequence” (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:541–547. doi: 10.1038/nbt1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Field D, Amaral-Zettler L, Cochrane G, Cole JR, Dawyndt P, Garrity GM, et al. The genomic standards consortium. PLoS Biol. 2011;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4576–4579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen WX, Wang ET, Kuykendall LD. The Proteobacteria. New York: Springer - Verlag; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Validation of publication of new names and new combinations previously effectively published outside the IJSEM. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:2235–2238. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn TE. Class II. Betaproteobacteria. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Volume 2. Second edition. New York: Springer - Verlag; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn TE. Order 1. Burkholderiales. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Volume 2. Second edition. New York: Springer - Verlag; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Liburn T. Family I. Burkholderiaceae. In: Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Volume 2 part C. New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 438–475. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palleroni NJ. Genus I. Burkholderia. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Volume 2. Second edition. New York: Springer - Verlag; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]