Abstract

Skin pigmentation in animals is an important trait with many functions. The present study focused on two closely related salmonid species, marble trout (Salmo marmoratus) and brown trout (S. trutta), which display an uncommon labyrinthine (marble-like) and spot skin pattern, respectively. To determine the role of chromatophore type in the different formation of skin pigment patterns in the two species, the distribution and ultrastructure of chromatophores was examined with light microscopy and transmission electron microscopy. The presence of three types of chromatophores in trout skin was confirmed: melanophores; xanthophores; and iridophores. In addition, using correlative microscopy, erythrophore ultrastructure in salmonids was described for the first time. Two types of erythrophores are distinguished, both located exclusively in the skin of brown trout: type 1 in black spot skin sections similar to xanthophores; and type 2 with a unique ultrastructure, located only in red spot skin sections. Morphologically, the difference between the light and dark pigmentation of trout skin depends primarily on the position and density of melanophores, in the dark region covering other chromatophores, and in the light region with the iridophores and xanthophores usually exposed. With larger amounts of melanophores, absence of xanthophores and presence of erythrophores type 1 and type L iridophores in the black spot compared with the light regions and the presence of erythrophores type 2 in the red spot, a higher level of pigment cell organisation in the skin of brown trout compared with that of marble trout was demonstrated. Even though the skin regions with chromatophores were well defined, not all the chromatophores were in direct contact, either homophilically or heterophilically, with each other. In addition to short-range interactions, an important role of the cellular environment and long-range interactions between chromatophores in promoting adult pigment pattern formation of trout are proposed.

Keywords: iridophore, melanophore, pigment pattern, Salmo, transmission electron microscopy, xanthophore

Introduction

Knowledge of the mechanisms responsible for the formation and maintenance of phenotypic diversity is key to understanding the evolution of morphological characters in living organisms. In fish, skin pigmentation is an important trait with many functions. For example, it has a significant role in intra-specific communication (e.g. mate choice) and inter-specific interactions (e.g. camouflage; Kelsh, 2004). Many pigments can also have other adaptive functions, such as photoprotection, structural support, microbial resistance and thermoregulation, while variation in pigment patterns is considered as one of the driving forces of speciation (for review, see Hubbard et al. 2010).

Skin pigmentation in fishes is one of the most pronounced phenotypic traits, as they tend to display a variety of colours and a wide range of patterns formed by several pigment cell types (chromatophores), including melanophores, iridophores, xanthophores, erythrophores, leucophores and cyanophores (Fujii, 2000; Burton, 2002). Beginning in the last century, several studies have been undertaken that describe pigment cells in different fish species (Warren, 1932; Takeuchi & Kajishima, 1972; Hawkes, 1974; Harris & Hunt, 1975; Takeuchi, 1976). Still, studies of detailed ultrastructure and organisation of pigment cells in fish skin are rare, and limited to either model species (zebrafish, Danio rerio; Hirata et al. 2003, 2005) or economically (turbot, Scophthalmus maximus; Zhu et al. 2003; Guo et al. 2007) or aquaristically (guppies, Poecilia reticulate; Kottler et al. 2014) important species.

The Salmonidae family is known for its great variation in skin pigmentation and pigment patterning at both inter- and intra-specific levels. However, the mechanisms leading to such variation, including chromatophore structure and interaction among chromatophores, are mostly unknown. Skin pigmentation in salmonids depends on melanophores, xanthophores, iridophores and erythrophores (Leclercq et al. 2010), the arrangement of which generates the adult pigment pattern that is comprised of specifically distributed and differently coloured and shaped spots. In salmonids, the limited information available on chromatophore ultrastructure refers to Atlantic salmon, S. salar (Harris & Hunt, 1975), coho salmon, Onchorhynchus kisutch (Hawkes, 1974), brook trout, S. fontinalis, brown trout, S. trutta m. fario and rainbow trout, O. mykiss (Kaleta, 2009). All authors describe three general classes of pigment cells – melanophores, xanthophores and iridophores – with the last of these having at least two distinct types; being distinguished by the shape of the cell (globular and elongated or dendritic iridophores; Hawkes, 1974; Kaleta, 2009) or by the size of their inclusions (Hirata et al. 2003). Iridophores have inclusions with a unique shape of rhomboidal platelets that contain purines (mainly guanine; Harris & Hunt, 1975; Rohrlich & Rubin, 1975), while melanophores contain deposited melanoprotein (Fujii, 1993) stored in organelles called melanosomes, and xanthophores can have two types of pigment organelles, called xanthosomes (called also pterinosomes, storing pteridines) and carotenoid vesicles (storing carotenoids; Matsumoto, 1965; Obika & Meyer-Rochow, 1990; Obika, 1992).

The arrangement of chromatophores is considered more varied and less highly organised in fish than in amphibians or reptiles (Bagnara & Matsumoto, 2006; Nordlund et al. 2006), although in zebrafish pigment cells in the skin follow a strict organisation (Hirata et al. 2003). The melanophores are frequently described as structurally associated with iridophores. However, none of the authors described the presence of erythrophores in the skin of salmonid fish, though this type of pigment cell was mentioned by Leclercq et al. (2010) as a fourth chromatophore in Atlantic salmon skin, covering melanophores from outside-in and resulting in a red ring and, eventually, a plain red mark. Unfortunately, no figure or detailed characteristics of erythrophores were provided in that review. It is nevertheless well recognised that erythrophores as xanthophores can contain two kinds of pigment organelles, carotenoid vesicles and xanthosomes, the relative proportion of which distinguishes these two chromatophores although sometimes arbitrarily (Matsumoto, 1965; Leclercq et al. 2010). Namely, many studies on xanthophores or erythrophores describe a very similar cell ultrastructure (Matsumoto & Obika, 1968; Obika, 1992; Ichikawa et al. 1998).

The present study focused on two salmonid species, marble trout (S. marmoratus) and brown trout (S. trutta). Although they are phylogenetically closely related (Pustovrh et al. 2014), they exhibit a different skin pigment pattern. Whereas brown trout exhibit a spotted pattern, marble trout have an uncommon labyrinthine (marble-like) pattern (Fig.1). The labyrinthine pattern is not commonly observed among trout, though it is characteristic of autochthonous trout of the Adriatic drainage and, in a more limited range, of a population of brown trout inhabiting the River Otra, Norway (Skaala & Solberg, 1997). This characteristic pattern has also been observed in some hybrids between species of different salmonid genera [e.g. S. trutta × S. fontinalis (brook trout); Miyazawa et al. 2010]. It is more often found in marine fish species [e.g. pufferfish (Takifugu exascurus)] and in some zebrafish mutants (e.g. Cx41.8M7; Watanabe & Kondo, 2012), partially in jaguar/obelix (Iwashita et al. 2006). However, for the majority of these species, no morphological features of skin and pigment cell ultrastructure have to the authors’ knowledge been described, except for the position of pigment cells in the skin of the aforementioned zebrafish mutant Cx41.8M7 (Watanabe M., Nishida T. & Kondo S., personal communication), and the description of basic morphological features and histochemical differences of marble and brown trout skin (Sivka et al. 2012). The basic structure of skin of marble and brown trout individuals corresponds with that described for other salmonids, with melanophores present in both species only in the dermis, being bigger in marble trout but present at a lower average density than in brown trout. In adult marble trout with fully established labyrinthine pigmentation, light areas are characterised by smaller size melanophores present at lower density than in darker areas, while in brown trout melanophores are more uniformly distributed (Sivka et al. 2012).

Fig 1.

(A) Brown trout with skin pigment pattern formed from black and red spots set in a pale background. (B) Marble trout with labyrinthine skin pigment pattern. Black boxes indicate the area of the skin along the lateral part of the trunk used for sections analysed in this study.

The cellular and genetic background of skin pigment pattern formation is a complex process and one that is not yet completely understood. Observable colours are primarily dependent upon the morphology, density and distribution of the pigment cells within the integument (Leclercq et al. 2010). For zebrafish, vertical organisation of the chromatophores has been described (Hirata et al. 2003, 2005) with, downwards from the surface, xanthophores, type S iridophores, melanophores and type L iridophores found in the dark stripe region, and xanthophores and type S iridophores in the inter-stripe region. Similar patterns of organisation have been found in other fish species, though in general chromatophores in teleosts are not necessarily organised into strict layers (Kaleta, 2009; Kottler et al. 2014), while many studies (Takahashi & Kondo, 2008; Inaba et al. 2012; Frohnhöfer et al. 2013; Irion et al. 2014; Patterson et al. 2014; Yamanaka & Kondo, 2014) suggest that chromatophore interactions play an essential role in the pigment pattern formation. Ultrastructural analysis of pigment cells and their position in the labyrinthine patterned skin of marble trout, compared with the spot pattern on brown trout skin, will lead towards a better understanding of how these cells interact and whether a different position or interaction, or both, might be characteristic of the labyrinthine pigment pattern formation.

The present study tested whether differences exist between marble trout and brown trout in the presence, distribution and ultrastructural organisation of the chromatophores that could indicate possible cell–cell interactions involved in pattern formation. The structure of the skin of these trout species, especially the dermis and the pigment cells, was analysed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Through this method it was possible to determine the shape of individual pigment cell types, as well as their ultrastructure and location in the dermis, and draw conclusions and further hypotheses on their interactions and cellular processes involved in the formation of pigment pattern in the two species.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

Adult marble trout individuals (2+) were obtained from Tolminka fish farm in Tolmin, Slovenia; and adult brown trout (2+) from Bled fish farm, Bled, Slovenia. Within the age of 2 years trout had reached sexual maturity and had already developed their adult skin pattern. The body length of the individuals ranged from 25 to 31 cm. All fish were first generation individuals reared in the fish farm, and descended from wild-caught parents originating from Zadlaščica (marble trout) and Malešnica streams (brown trout), Slovenia. The fish were fed with Biomar INICIO Plus (Denmark) as a starter feed and Biomar EFICO Enviro 920 when adult.

Prior to skin sample collection, fish were sedated in anaesthetic Tricaine-S (MS-222; Western Chemical, Ferndale, WA, USA) and killed by a blow to the neck. Treatment of the animals was carried out following the national regulations and decision letter U34401-60/2013/4 issued by the Ministry of Agriculture and Environment for performing research activities on fish tissues.

Light microscopy and TEM

Skin samples of marble trout and brown trout were dissected and observed directly under a light microscope (Nikon Eclipse, TE-2000U). Small pieces of skin from the lateral part of the trunk of the body (Fig.1) were obtained with 2 mm biopsy punch (Kai Group, Japan) to selectively dissect differently pigmented regions of skin in marble trout (light and dark region) and brown trout (light region, black and red spots). Skin samples were immersed in a mixture of 3% paraformaldehyde and 3% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 m cacodylate buffer, and fixed overnight at 4 °C and subsequently in 2% osmium tetraoxide for 2 h at room temperature. Samples were stained en bloc with 2% uranyl acetate in 50% methanol for 2 h, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol solutions and embedded in epon812 resin (Serva Electrophoresis, Heidelberg, Germany). Semi-thin (1 μm) and ultra-thin (65 nm) sections were cut using an Ultracut UCT microtome (Leica, Austria). Semi-thin sections were contrasted with toluidine blue and examined under the light microscope to determine the position of pigment cells. Regions observed by TEM were selected on the basis of the preliminary analysis of the semi-thin sections by light microscope. Ultra-thin sections were contrasted with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined with a Philips CM100 TEM for cell ultrastructure analysis.

Results

Epidermis structure in the skin of marble trout and brown trout

No pigment cells were observed in the epidermis, which consisted of epithelial cells and a large number of two types of morphologically identical secretory cells (goblet and sacciform cells; Pickering & Fletcher, 1987; Figs2 and 4). The structure of the epidermis consisted of a non-keratinizing stratified squamous epithelium, formed by columnar epithelial cells (Fig.5A) upon the basal lamina and a more flattened morphology in the upper region (Fig.2A–C).

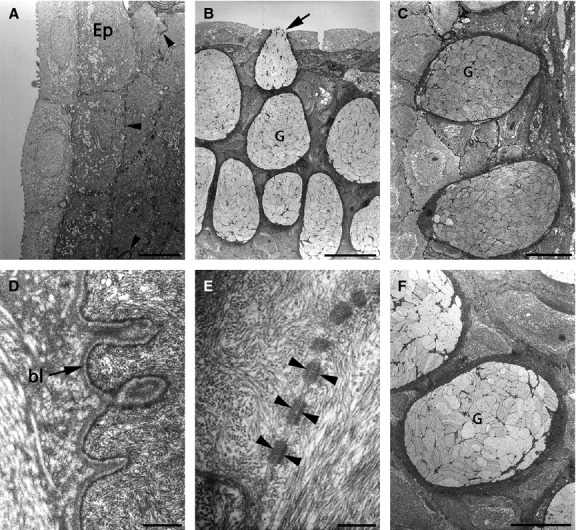

Fig 2.

Ultrastructure of epidermis with epithelial and secretory cells. Many desmosomes connecting epithelial cells are visible (arrowheads in A and E). (B, C, F) Large goblet cells filled with many secretory vesicles. (B) Goblet cell secreting acid proteoglycans (arrow). (D) Basal lamina separating the epidermis from the dermis. There were no pigment cells in the epidermis. bl, basal lamina; Ep, epidermis; G, goblet cell. Scale bars: 5 μm (A); 20 μm (B); 10 μm (C and F); 500 nm (D); 200 nm (E).

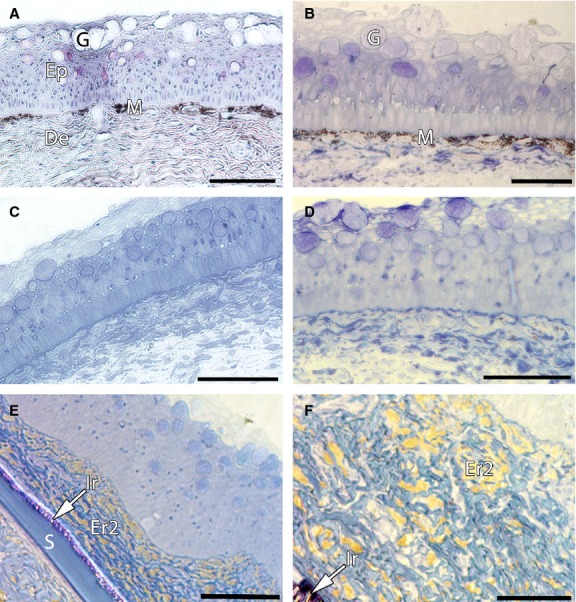

Fig 4.

Semi-thin sections from the skin of marble trout and brown trout. (A, C) Semi-thin sections from the skin of marble trout showing more melanophores present just under the epidermis in the dark region (A) than in the light region (C). (B, D–F) Semi-thin sections from the skin of brown trout. (B) Dark spot region with a melanophore layer located in the stratum compactum. (D) Light region. (E, F) Semi-thin sections from the red spot region with erythrophores (type 2) containing red pigment (carotenoids); arrows indicate iridophores present on the scale. Big goblet cells in the epidermis of both species can be seen (A–E). De, dermis; Ep, epidermis; Er2, type 2 erythrophores; G, goblet cells; Ir, type S iridophores; M, melanophores; S, scale. Scale bars: 100 μm (A–E); 50 μm (F).

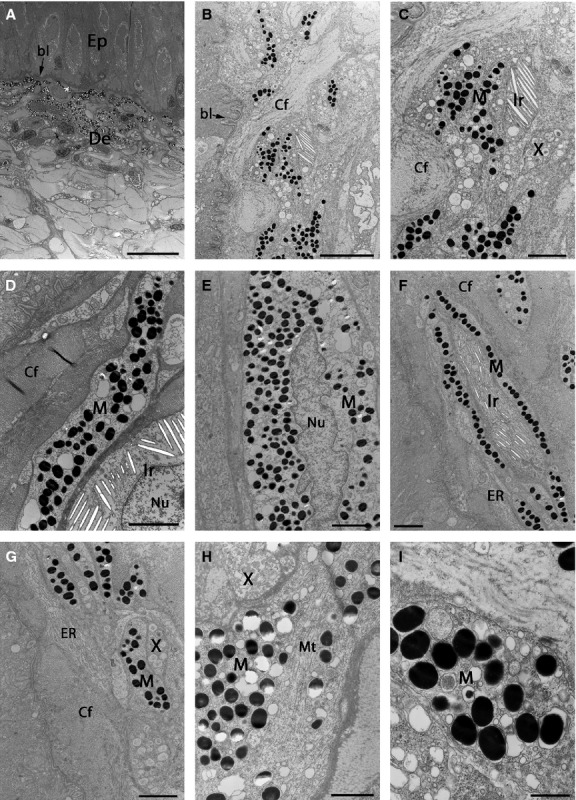

Fig 5.

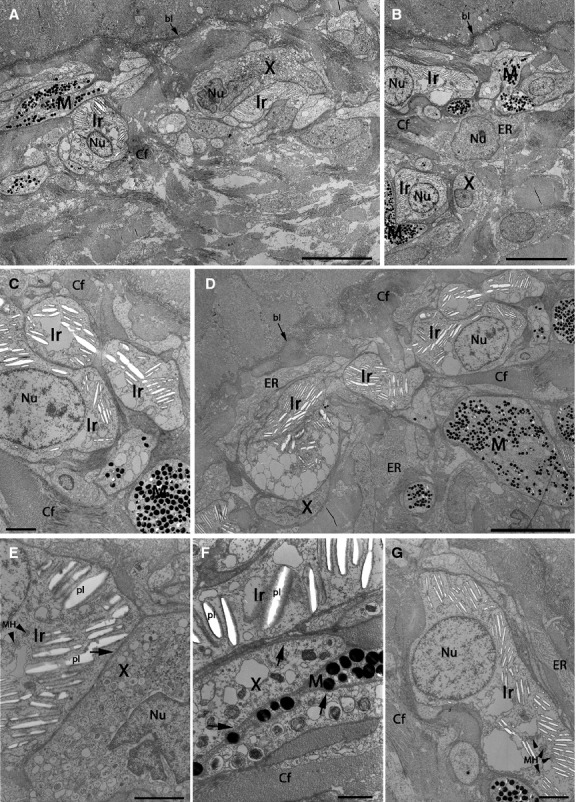

TEMs showing pigment cells in the dark region of marble trout skin. (A, B) Low-magnification image of the area between the dermis and epidermis. The skin surface is at the top in (A) and on the left in (B). All three pigment cell types are present, with melanophores more common and usually in the upper dermis compared with iridophores and xanthophores. (C) Higher-magnification image showing all three pigment cell types. (D) Melanophore–iridophore connection at the beginning of the dermis, surrounded by collagen fibres. (E) Melanophore with an irregular-shaped nucleus. (F) Melanophore surrounding the iridophore. (F, G) Different connections between pigment cells in the dermis. Collagen fibres are surrounding individual or small clusters of pigment cells. Cells filled with closely packed sheets of granular ER are often found in the proximity of pigment cells. The skin surface is on the left. (H) Melanophore with microtubules in the cytoplasm. (I) Melanophore ultrastructure with round electron-dense melanosomes. bl, basal lamina; Cf, collagen fibres; De, dermis; Ep, epidermis; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; Ir, type S iridophores; M, melanophores; Mt, microtubule; Nu, nucleus; X, xanthophores. Scale bars: 20 μm (A); 5 μm (B); 2 μm (C–G); 1 μm (H); 500 nm (I).

Pigment cells in dermis of marble trout and brown trout

The presence of three pigment cell types (melanophores, iridophores and xanthophores) in the skin of marble trout and brown trout was confirmed (Figs8). In addition, a fourth type of pigment cell in the skin of brown trout, erythrophores, was characterised (Figs3F, 7B,F–G and 9A–E), and further their ultrastructure and exact positioning in the skin determined.

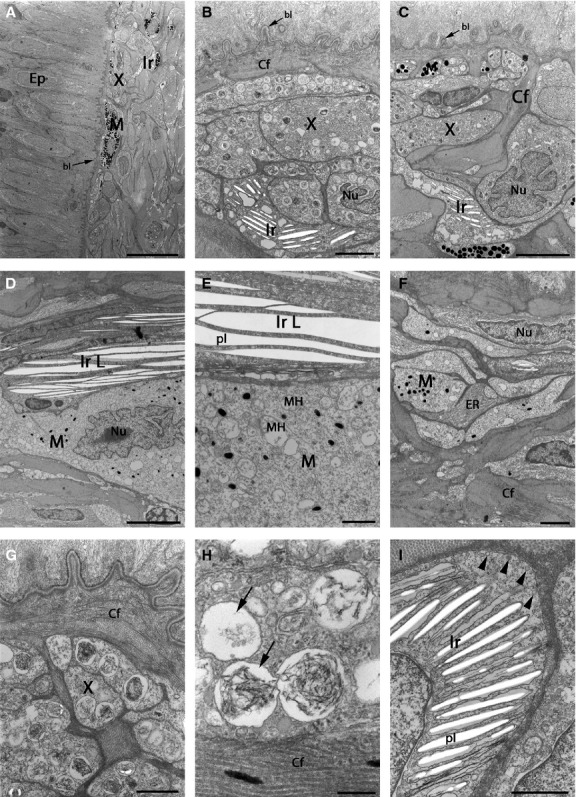

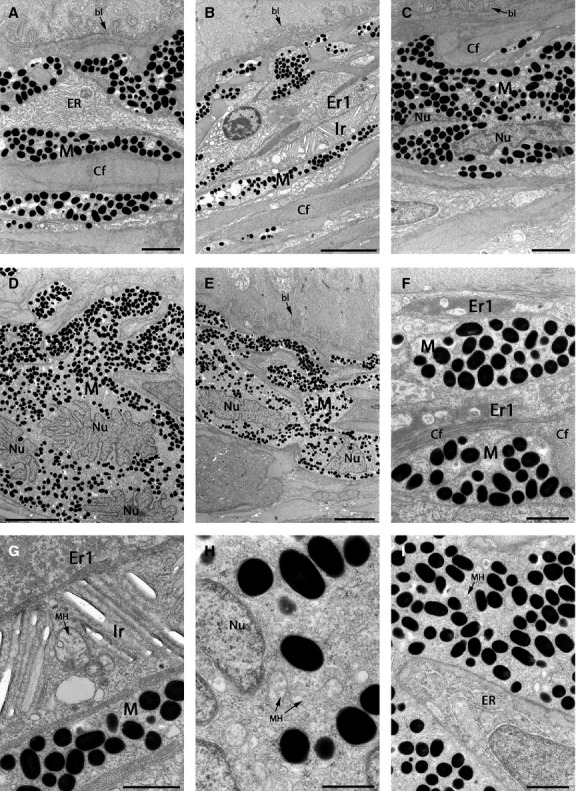

Fig 8.

TEMs showing pigment cells in the light region of brown trout skin. Skin surface is to the left (A) and to the top (others). (A–G) Pigment cells present in the light region are mainly xanthophores and iridophores. Melanophores are absent (B), or rare (A, C), usually with scarce melanosome content (D–F). (B–D) Pigment cell nucleus can have an irregular shape. (D, E) Type L iridophores, found only in the light region of brown trout skin. (E) Higher-magnification of type L iridophores and melanophores with only a few small melanosomes and several mitochondria. (F) Besides collagen fibres there are cells with ribosomal ER in contact with pigment cells. (G) Xanthophores surrounded by collagen fibres. (H) Ultrastructure of pterinosomes in xanthophores, with some parts containing lamellar insertions, while other parts are empty (arrows). (I) Iridophore with many parallel platelets and a large number of vesicles near the plasma membrane (arrowheads). bl, basal lamina; Cf, collagen fibres; Ep, epidermis; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; Ir, type S iridophores; IrL, type L iridophores; M, melanophores; MH, mitochondria; Nu, nucleus; pl, platelets; X, xanthophores. Scale bars: 20 μm (A); 2 μm (B and F); 5 μm (C and D); 1 μm (E, G and I); 200 nm (H).

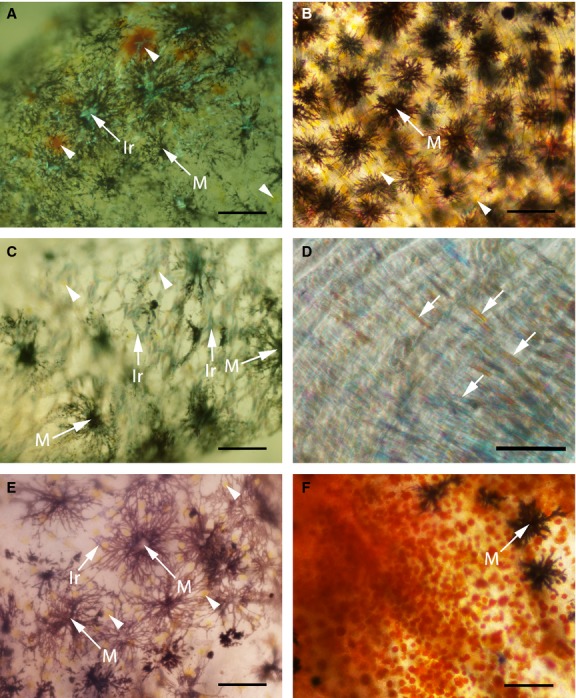

Fig 3.

Three pigment cell types under light microscope in the skin of marble (A, C and E) and four pigment cell types in the skin of brown trout (B, D and F). (D) Iridophores covering a part of the extracted scale (arrows). (F) Red spot area with red coloured erythrophores (type 2) and some melanophores. Arrowheads indicate xanthophores; Ir, iridophores; M, melanophores. Scale bars: 100 μm (A–C, E and F); 50 μm (D).

Fig 7.

TEMs showing pigment cells in the black spot region of brown trout skin. Skin surface is at the top. (A–E) The beginning of the dermis with a melanophore layer usually immediately below the basal lamina. (C–E) Melanophores with an irregular shaped nucleus. (F) Melanophores with melanosomes and erythrophores (type 1) with carotenoid vesicles surrounded by collagen fibres. (G) Higher-magnification of three types of pigment cells [erythrophores (type 1), iridophore and melanophore]. Orientation of the iridophore platelets can differ in the same cell. Mitochondria in the iridophore centre (arrows). (H) Melanophore cytoplasm with round melanosomes, cell nucleus and mitochondria. (I) Melanophore in contact with a cell filled with ribosomal ER. bl, basal lamina; Cf, collagen fibres; Er1, type 1 erythrophores; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; Ir, type S iridophores; M, melanophores; MH, mitochondria; Nu, nucleus. Scale bars: 2 μm (A and C); 5 μm (B, D and E); 1 μm (F, G and I); 500 nm (H).

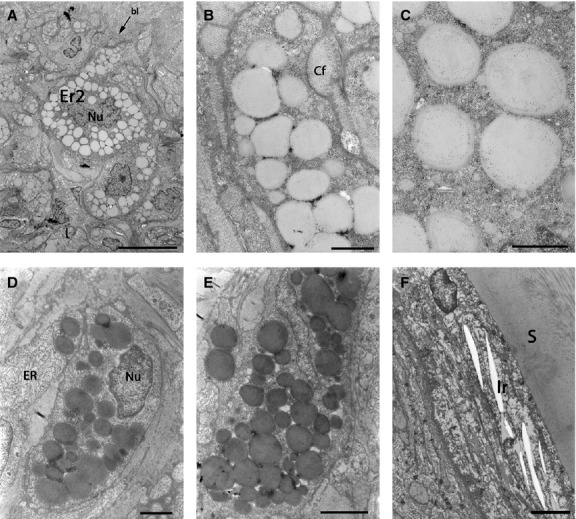

Fig 9.

TEMs showing pigment cells in the red spot region of brown trout skin. (A) Low-magnification showing erythrophores (type 2) as the only pigment cells present in this area. (A, D) Erythrophore cell nuclei with irregular shape. (A–E) Type 2 erythrophore ultrastructure is different from that of other pigment cells, but similar to type 1 erythrophores with carotenoid vesicles. (D, E) In some samples the inclusions appear still to be filled with carotenoid pigment. (F) Type S iridophores covering the scale. bl, basal lamina; Cf, collagen fibres; Er2, type 2 erythrophores; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; Ir, type S iridophores; Nu, nucleus; S, scale. Scale bars: 10 μm (A); 5 μm (B); 1 μm (C–E); 2 μm (F).

By light microscopy, it was observed that most of the pigment cells were positioned just under the epidermis, in the stratum compactum of the dermis in both species (Fig.4), while some isolated pigment cells were also noticed in a deeper layer, and also beneath the scale (data not shown).

In the dark spot of brown trout and dark region of marble trout skin, an almost continuous line of dark pigmented cells, that is melanophores (Fig.4A,B), was observed. Because of their black–brown colour and dendritic shape, they were the most easily observed cell type (Figs3A–C,E–F and 4A,B). They contained deposited melanoprotein with high electron density and thus appear black (Figs8). The melanophore nucleus often had an irregular shape with a wrinkled nuclear membrane (Figs5E, 7C–E and 8D). Therefore, in some sections it seemed that there was more than one nucleus present in a single cell (Fig.7D,E).

Xanthophores with two types of pigment organelles, called xanthosomes and carotenoid vesicles, were observed in marble trout skin and in the light area of brown trout skin (Figs5, 6 and 8). By light microscopy it was often impossible to establish the position of xanthophores due to pigment loss, though their position and ultrastructure were successfully determined with TEM. From the current observations, xanthosomes were always present in xanthophores. The size and shape of the xanthosomes was similar to those of melanosomes (0.5 μm in diameter) but with low electron density, usually containing some laminar insertions or sometimes appearing empty (Figs5, 6 and 8). Carotenoid vesicles were smaller (approximately 0.1 μm in diameter; Figs5B,C, 6E,F and 8) and contained carotenoid pigments. Depending on the type and amount of pigment they contained, xanthophores displayed a yellow (Fig.3A,C,E) to orange colour (Fig.3A).

Fig 6.

TEMs showing pigment cells in the light region of marble trout skin. (A–D) Low-magnification images of the area between the dermis and epidermis. The skin surface is at the top. All three pigment cells are present. The less abundant melanophores are usually located deeper in the dermis than in the dark region (B–D), with exceptions (A, B). Mainly iridophores or xanthophores are present in the uppermost layer of pigment cells. Iridophores are filled with differently oriented platelets or empty lacunas (where platelets are lost). (E) Direct contact between an iridophore and xanthophore. (F) Ultrastructure of three pigment cell types that are intermingled. (E, F) Vesicles in the cytoplasm of iridophores and xanthophores (arrows). (G) An iridophore with round cell nucleus and plenty of platelets. bl, basal lamina; Cf, collagen fibres; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; Ir, type S iridophores; M, melanophores; MH, mitochondria; Nu, nucleus; pl, platelets; X, xanthophores. Scale bars: 10 μm (A, B, D); 2 μm (C, E, G); 1 μm (F).

Iridophores contained crystalline platelets that were reflective under specific light, appearing as shining light rods that were difficult to detect when observing whole skin dissections (Fig.3A,C,D), but were easily recognised in semi-thin and ultra-thin sections because of the shape of their inserts: rhomboidal platelets. They contained purines that are responsible for the silver white colouration (Figs8 and 9F). Platelets had a parallel distribution and were found in two different sizes: globular iridophores with smaller platelets (1–2 μm) were identified as type S iridophores (Figs8); and those elongated (dendritic) with larger inserts (5–10 μm) as type L iridophores (Fig.8D,E). Type S iridophores were present in all differently pigmented skin regions of both species. Generally they contained from two to six differently orientated groups of crystalline platelets, with 2–20 parallel platelets in each group, and usually a round–oval nucleus. Type L iridophores were found only in the light region of brown trout skin. Apart from the bigger size of their platelets, the platelets were orientated in the same direction, parallel to the skin surface. Type L iridophores had a more elongated nucleus.

One more class of pigment cell was detected – observed initially by light microscopy of dissected whole skin samples: red–orange coloured erythrophores were found in two regions of brown trout skin – in black and red spots (Fig.3F). Moreover, by TEM, two distinct erythrophore types were also observed. In the black spot region, erythrophores were found with similar ultrastructural features as xanthophores but containing only a single type of pigment organelle: carotenoid vesicle and no xanthosome (type 1 erythrophore; Fig.7B,F,G). The second type of erythrophore (type 2) was a more distinct type of pigment cell, found using correlative microscopy only in red spot skin tissue of brown trout (Fig.9A–E). Cells appearing orange-reddish under a light microscope were found to be densely filled with one type of round organelle under TEM (Fig.9A–E). These organelles were similar to carotenoid vesicles found in the first type of erythrophore but with major differences in size, therefore named erythrosomes. Extending to 1 μm in diameter, they were much larger than inclusions of other pigment cells (Figs8), with melanosomes or xanthosomes being approximately 0.5 μm, and carotenoid vesicles approximately 0.1 μm in diameter.

It was noticed that mitochondria were seen more frequently in the cytoplasm of xanthophores, iridophores and erythrophores than in melanophores. As already mentioned for melanophores, also xanthophores and erythrophores contained an irregular-shaped cell nucleus (Figs6A,E, 8B–C and 9A,D, Nu) and several vesicles (Figs6E, F and 8I, arrows). Contrary to the findings of Faílde et al. (2014), an irregular-shaped nucleus in iridophores was rarely detected.

Even though the parts of the skin containing pigment cells were well defined, the pigment cells were not always in contact, either homophilically or heterophilically, with each other, but were sometimes separated by collagen fibres or non-pigmented cells (Figs9). The cytoplasm of cells located between pigment cells was often filled with closely packed sheets of granular endoplasmic reticulum (Figs5G, 6B,D, 7A,I and 8F), indicative of extremely active protein biosynthesis.

Comparison of pigment cell organisation in marble and brown trout

A dense band of melanophores was observed in the stratum compactum in the dark region of marble trout skin (Fig.5) and in the black spot region of brown trout skin (Fig.7). Whereas with light microscopy only melanophores were observed in such areas (Fig.4A,B), TEM analysis revealed more cell types (Table1). In addition to numerous melanophores, located in the uppermost layer and densely filled with melanosomes, type S iridophores, with empty parallel platelets (with loss of contents during preparation), were also found and usually located beneath melanophores in both species. Xanthophores, containing xanthosomes and carotenoid vesicles, were found in this area of marble trout skin, while erythrophores (type 1) with similar ultrastructure were found in the dark spot of brown trout skin. They contained only one type of pigment organelle with carotenoids but no xanthosomes.

Table 1.

Comparison of pigment cell organisation in the stratum compactum of the skin of marble and brown trout

| Skin region/species | Marble trout | Brown trout |

|---|---|---|

| Dark region/black spot | Melanophores, type S iridophores and xanthophores | Melanophores, type S iridophores, erythrophores (type 1) |

| Light region | Type S iridophores, xanthophores and melanophores | Xanthophores, type S iridophores, melanophores, type L iridophores |

| Red spot | Not present | Erythrophores (type 2), melanophores |

The written sequence of chromatophores corresponds to the amount of specific pigment cell type in specific area. Names written in bold are the types of pigment cells present only in the brown trout skin.

Xanthophores and type S iridophores predominated in the light regions of marble and brown trout (Figs6 and 8; Table1). Melanophores in the light region were very rare and generally located beneath xanthophores or iridophores (Fig.6B–D,G), but could also be found above them (Fig.6A,B). In the light region of brown trout skin (Fig.8), melanophores with fewer melanosomes were common (Fig.8D–F). In addition to type S iridophores (1–2 μm), also some type L iridophores (5–10 μm) were found in the light area of brown trout skin (Fig.8D,E, Ir L), which were not detected in other skin regions of brown trout or even marble trout. On the other hand, some globular type S iridophores were found positioned just above the scale in the light region of the marble trout skin (data not shown). Besides some isolated melanophores, mainly one type of pigment cell was found in the red spot region of brown trout skin – erythrophore type 2 (Fig.9A–E). As observed in semi-thin sections from this area (Fig.4E,F), some type S iridophores were found lower in the dermis, covering the scales (Fig.9F).

In both dark and light pigmented skin regions of marble and brown trout there were some pigment cells present also under the scales. They were usually clustered into small groups, and there was no difference between the black and light regions examined in the type and number of pigment cells.

Discussion

One of the main goals of the current research was to define the structure of the pigment cell layer in the skin of closely related species marble trout and brown trout, which exhibit very different skin patterns. The study revealed three classes of pigment cells (melanophores, iridophores and xanthophores) in the skin of marble trout, and four classes (melanophores, iridophores, xanthophores and erythrophores) in the skin of brown trout forming differently organised layers in the dermis. It has been already observed that pigment cells in teleosts are not always organised into strict layers (Leclercq et al. 2010). Nevertheless, it was an unexpected finding that the chromatophores in the two species of trout investigated here, displaying different skin patterns, did not have a strict order as observed in, for example, zebrafish (Hirata et al. 2003). In zebrafish skin, the pigment cells are layered into sheets that appear to have a strict order, confined to the dark and light striped region of skin pigmentation. Each sheet is composed of a single-cell-thick layer of one class of pigment cell. The mechanism underlying the layer order is likely to be selectively important, as the order of pigment cells in skin determines body colour, resistance to UV damage and pathogens, etc. (Nordlund et al. 2006), leading Hirata et al. (2005) to hypothesise that there is a common mechanism to form such an ordered structure. The arrangement into layers and the contact between pigment cells seems necessary for stripe formation in zebrafish. In stripe-less regions of the zebrafish trunk the layering differs, and there is no type L iridophore layer, while melanophores are not in direct contact with type S iridophores (Hirata et al. 2005). In the zebrafish mutant Cx41.8M7, which exhibits a labyrinthine pigment pattern, similar to that of the skin of marble trout, organised layers of pigment cells with a vertical order of the sheets have been also discovered: type S iridophores and melanophores in the dark skin region; and type S iridophores and xanthophores in the light skin region (Watanabe M., Nishida T. & Kondo S., personal communication).

The skin of trout consists of several cell layers. Here it was found that the structure of the epidermis of marble trout and brown trout was similar to that described previously for other fish species (Hawkes, 1974; Harris & Hunt, 1975; Faílde et al. 2014). However, the arrangement of chromatophores in the dermis was more varied than in zebrafish, though with some similarities to the findings of a study on turbot (Faílde et al. 2014), which reported a vertical order of dermal chromatophores, with melanophores and xanthophores located in the uppermost layer and iridophores in the basal layer. A similar organisation was found in dark pigmented regions of both species, with the majority of melanophores located in the upper layer, just beneath the basal lamina and other types of pigment cells lying underneath. In the light area of trout skin the pigment cell arrangement was almost reversed, with intermingling of xanthophores and iridophores covering the much less common melanophores. In both species, melanophores had an irregular-shaped nucleus, sometimes appearing as though there were more nuclei present in one cell (Fig.7D,E). Because the melanophores are large dendritic cells (up to 500 μm in diameter), it would be possible for them to contain more than one nucleus, as already observed in zebrafish melanophores (Yamanaka & Kondo, 2015). Another possible explanation for this observation is that the nucleus sometimes has an irregular arborescent shape. Although such an irregular-shaped nucleus in xanthophores and iridophores has been described previously, a round–oval cell nucleus was described for fish melanophores (Faílde et al. 2014). Apart from the cell nucleus, numerous melanosomes and occasionally microtubules (Fig.5H) were also detected.

Besides layering arrangements, other forms of pigment cell organisation have been reported elsewhere. In the skin of reptiles and amphibians, pigment cells always form chromatophore units composed of the same layered structure of three classes of pigment cells – xanthophores, iridophores and melanophores (Bagnara et al. 1968) – perhaps indicating a conserved mechanism of chromatophore patterning. However, different authors are not in agreement over the presence of these units in the skin of fish. According to Hawkes (1974) and Kaleta (2009), chromatophore units are also found in fish skin, while Bagnara & Ferris (1971) report no such structural or functional units, but rather just individual cell responses. Hawkes (1974) reported the existence of chromatophore units in the skin of coho salmon, but only on non-scaly skin overlying the head. In the scaly skin there were only small clusters of iridophores and melanophores scattered in the collagen above the stratum compactum, while deeper melanophores interdigitated with iridophores rather than forming any type of encircling association, and xanthophores were randomly distributed. Here, it is shown that the scaly skin of brown trout does not show such a specific association: the pigment cells of different classes were intermingled, apparently randomly, and did not show a consistent pattern or specific interactions between two isolated types of chromatophores. Although chromatophore units could not be identified in the skin of marble and brown trout, some clusters of two–three types of pigment cells surrounded with collagen were found (Figs5B,C,F, 6 and 8B,F). Kaleta (2009) analysed three salmonid species from three different genera and characterised by different skin pigmentation, but no comparison among the presence, distribution and ultrastructure of chromatophores (melanophores, iridophores and xanthophores) was reported. Just as Hawkes (1974) noticed for coho salmon, Kaleta (2009) pointed to cooperation between melanophores and globular or elongated iridophores in the formation of skin pigmentation in other salmonid species, with both chromatophore types forming clusters. Kaleta (2009) hypothesised that dendritic melanophores encompass the iridophores and by doing so absorb the incoming light in the dark region. Meanwhile, in the light region clusters of iridophores are associated with aggregated melanophores, resulting in the exposure of iridophores to light and thus producing light colours. In contrast, the presence of such pigment cell complexes in the skin of brown or marble trout was not confirmed in the present study. Nevertheless, it can be concluded that the difference in the light and dark colouration depends primarily upon the position and density of melanophores, in the dark region covering other pigment cells, and in the light region leaving the iridophores and xanthophores fully exposed.

Data on erythrophore ultrastructure in fish skin are very scarce. For salmonids, only Leclercq et al. (2010) has reported their presence, in the skin of Atlantic salmon, while Matsumoto (1965) analysed their ultrastructure in the skin of swordtail (Xiphophorus helleri) and Matsumoto & Obika (1968) in the skin of goldfish (Carassius auratus). As there are the same types of chromatophores present in the skin of reptiles and amphibians (Ichikawa et al. 1998), the erythrophore structure in the skin of brown frog (Rana ornativentris) was also used for comparison between species. The authors characterised erythrophores as extremely similar to xanthophores, with both cell types containing xanthosomes (pterinosomes) or carotenoid vesicles, or both. The distinction between these two types of chromatophores in the brown frog was based mainly on the size and inner structure of xanthosomes, being bigger and less uniform in xanthophores than in erythrophores. Matsumoto & Obika (1968) even suggested that erythrophores derive from xanthophores. Based on the general knowledge about pigments in different pigment cell type (Leclercq et al. 2010) and on previous ultrastructural studies of pigment cells (Obika, 1992; Hirata et al. 2003), two types of erythrophores were described in this study: both of them containing one type of pigment organelle and both without xanthosomes. Type 1 is similar to xanthophores, though containing only carotenoid vesicles and was present only in the black spot of brown trout skin. The structure of the carotenoid vesicle is the same as observed in xanthophores and in other studies (Obika & Meyer-Rochow, 1990; Obika, 1992; Ichikawa et al. 1998). Type 2 erythrophores were located exclusively in red spot skin sections and characterised by a unique type of chromatosomes, structurally distinct in size and shape compared with carotenoid vesicles of type 1 erythrophores and to the authors’ knowledge not described in trout skin so far. Because of the unknown chemical structure of their contents, they were named according to their colour as erythrosomes.

Great differences between marble and brown trout in the position of pigment cells were found. Finding a larger amount of melanophores, an absence of xanthophores and the presence of erythrophores (type 1) and type L iridophores in the black spot compared with the light region and the presence of erythrophores (type 2) in the red spot, it can be concluded that in the skin of brown trout there is a higher diversity and a higher level of organisation established (Table1). In contrast, the arrangement of chromatophores in the skin of marble trout was more varied and less organised, even though differences between dark and light regions were observed: a higher density and superficial positioning of melanophores was noted for the dark region, with a larger amount of xanthophores and iridophores found in the light region.

How can such intermingled pigment cell interactions without a layered structure help in the identification of the mechanisms of pigment pattern formation? Many recent studies have demonstrated the importance of cell–cell interaction in the formation of skin pattern (Takahashi & Kondo, 2008; Inaba et al. 2012; Frohnhöfer et al. 2013; Irion et al. 2014; Patterson et al. 2014; Yamanaka & Kondo, 2014), and thus this interaction may well have an important role in trout skin pattern formation. The current findings suggest that there is a more strict organisation and by that more specific interactions between cells in the skin of brown trout than in that of marble trout. Erythrophores are present in a very limited part of brown trout skin, in both dark and red spots. The presence of erythrophore type 1 in the dark spot of brown trout is the most intriguing, as this cell class was absent from the dark region of marble trout skin. This cell class could have a specific role in determining the pigment pattern, promoting the formation of dark spots in brown trout skin, through increased aggregation of melanophores in this region when compared with melanophore distribution in the dark region of marble trout. It is therefore hypothesised that melanophore–xanthophore and melanophore–erythrophore (type 1) interactions play an important role in pigment pattern formation in trout, and any direct or indirect role of iridophores in promoting or inhibiting these interactions must not be overlooked. Direct contacts between pigment cells were not always observed in trout skin, but recent studies on zebrafish have shown that direct contact between pigment cells might not be essential for pigment pattern formation, not precluding the important role of the cellular environment and long-range interactions in promoting adult pigment pattern formation (Nakamasu et al. 2009; Patterson & Parichy, 2013; Patterson et al. 2014). Those findings specifically address the role of iridophores in the promotion of differentiation and localisation of xanthophores at short range and repression of their differentiation at long range. As for melanophores, iridophores influence their distribution either directly or indirectly, presumably through a combination of short-range inhibition and long-range attraction. The network of pigment cell interaction is probably even more complicated in trout due to the existence of the fourth pigment cell class, the interaction of which with other pigment cells has not yet been studied. The abundance and distribution of particular pigment cell classes can limit the sort of interactions in which cells participate, with consequences for the pattern that develops (Patterson et al. 2014).

While the results of the current study indicate that marble trout and brown trout have a different pigment cell organisation than other fish species, this does not preclude the existence of a universal cellular interaction (direct or indirect) driving the pigment pattern formation process. From the current observations, an overall conclusion on which interaction or type of cells are the most important for pigment patterning in the skin of these two species of trout cannot be drawn, but it was possible to detect differences in the abundance and distribution of different pigment cell types, which could affect the pattern formation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tolmin Angling Club and Bled Fishing Club for providing samples. Special thanks go to Linda Štrus, Sanja čabraja and Sabina Železnik from the Institute of Cell Biology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ljubljana for technical assistance. Many thanks go to Iain F. Wilson for English revision of the manuscript. This study was supported by the Slovenian Research Agency through its financing of the postgraduate study and research training of PhD student Ida Djurdjevič, and research programmes P4-0220 and P3-0108. The authors would also like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions, which substantially improved the original version of the manuscript.

Authors’ contribution

All three authors contributed to the design of the experiments. I.D. and M.E.K. performed the experiments and acquired the data. I.D. and S.S.B. wrote the original manuscript, and S.S.B. and M.E.K. critically revised and approved the paper.

References

- Bagnara JT, Ferris WR. Interrelationship of vertebrate chromatophores. In: Kawamura T, Fitzpatrick TB, Seiji M, editors. Biology of the Normal and Abnormal Melanocyte. Tokyo: Univ. Tokyo Press; 1971. pp. 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bagnara JT, Matsumoto J. Comparative anatomy and physiology of pigment cells in nonmammalian tissues. In: Nordlund JamesJ, Boissy RaymondE, Hearing VincentJ, King RichardA, Oetting WilliamS, Ortonne Jean-Paul., editors. The Pigmentary System: Physiology and Pathophysiology. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2006. pp. 11–59. [Google Scholar]

- Bagnara JT, Taylor JD, Hadley ME. The dermal chromatophore unit. J Cell Biol. 1968;38:67–79. doi: 10.1083/jcb.38.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton D. The physiology of flatfish chromatophores. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;58:481–487. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faílde LD, Bermudez R, Vigliano F, et al. Morphological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural characterization of the skin of turbot (Psetta maxima L.) Tissue Cell. 2014;46:334–342. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohnhöfer HG, Krauss J, Maischein HM, et al. Iridophores and their interactions with other chromatophores are required for stripe formation in zebrafish. Development. 2013;140:2997–3007. doi: 10.1242/dev.096719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii R, et al. Cytophysiology of fish chromatophores. Int Rev Cytol. 1993;143:191–216. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii R. The regulation of motile activity in fish chromatophores. Pigment Cell Res. 2000;13:300–319. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0749.2000.130502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Huang B, Qi F, et al. Distribution and ultrastructure of pigment cells in the skins of normal and albino adult turbot, Scophthalmus maximus. Chin J Oceanol Limnol. 2007;25:199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Harris JE, Hunt S. The fine structure of the epidermis of two species of salmonid fish, the atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) and the brown trout (Salmo trutta L.) Cell Tissue Res. 1975;157:553–565. doi: 10.1007/BF00222607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes JW. The structure of fish skin. Cell Tissue Res. 1974;149:147–158. doi: 10.1007/BF00222270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata M, Nakamura K, Kanemaru T, et al. Pigment cell organization in the hypodermis of zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 2003;227:497–503. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata M, Nakamura K, Kondo S. Pigment cell distributions in different tissues of the zebrafish, with special reference to the striped pigment pattern. Dev Dyn. 2005;234:293–300. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard JK, Uy JA, Hauber ME, et al. Vertebrate pigmentation: from underlying genes to adaptive function. Trends Genet. 2010;26:231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa Y, Ohtani H, Miura I. The erythrophore in the larval and adult dorsal skin of the brown frog, Rana ornativentris: its differentiation, migration, and pigmentary organelle formation. Pigment Cell Res. 1998;11:345–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1998.tb00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba M, Yamanaka H, Kondo S. Pigment pattern formation by contact-dependent depolarization. Science. 2012;335:677. doi: 10.1126/science.1212821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irion U, Frohnhöfer HG, Krauss J, et al. Gap junction composed of connexins 41.8 and 39.4 are essential for colour pattern formation in zebrafish. eLIFE. 2014;3:1–16. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwashita M, Watanabe M, Ishii M, et al. Pigment pattern in jaguar/obelix zebrafish is caused by a Kir7.1 mutation: implications for the regulation of melanosome movement. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaleta K. Morphological analysis of chromatophores in the skin of trout. Bull Vet Inst Pulawy. 2009;53:117–121. [Google Scholar]

- Kelsh RN. Genetics and evolution of pigment patterns in fish. Pigment Cell Res. 2004;17:326–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2004.00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kottler VA, Koch I, Flötenmeyer M, et al. Multiple pigment cell types contribute to the black, blue, and orange ornaments of male guppies (Poecilia reticulata. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq E, Taylor JF, Migaud H. Morphological skin colour changes in teleosts. Fish Fish. 2010;11:159–193. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto J. Studies of fine structure and cytochemical properties of erythrophores in swordtail, Xiphophorus helleri, with special reference to their pigment granules (pterinosomes) J Cell Biol. 1965;27:493–504. doi: 10.1083/jcb.27.3.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto J, Obika M. Morphological and biochemical characterization of goldfish erythrophores and their pterinosomes. J Cell Biol. 1968;39:233–249. doi: 10.1083/jcb.39.2.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa S, Okamoto M, Kondo S. Blending of animal colour patterns by hybridization. Nat Commun. 2010;1:66. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamasu A, Takahashi G, Kanbe A, et al. Interactions between zebrafish pigment cells responsible for the generation of Turing patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:8429–8434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808622106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordlund JJ, Boissy RE, Hearing VJ, et al. The Pigmentary System: Physiology and Pathophysiology. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Obika M. Formation of pterinosomes and carotenoid granules in xanthophores of the teleost Oryzias latipes as revealed by the rapid-freezing and freeze-substitution method. Cell Tissue Res. 1992;271:81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Obika M, Meyer-Rochow VB. Dermal and epidermal chromatophores of the Antarctic teleost Trematomus bernachii. Pigment Cell Res. 1990;3:33–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1990.tb00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson LB, Parichy DM. Interactions with iridophores and the tissue environment required for patterning melanophores and xanthophores during zebrafish adult pigment stripe formation. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson LB, Bain EJ, Parichy DM. Pigment cell interactions and differential xanthophore recruitment underlying zebrafish stripe reiteration and Danio pattern evolution. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5299. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering AD, Fletcher JM. Sacciform cells in the epidermis of the brown trout, Salmo trutta, and the Arctic char, Salvelinus alpinus. Cell Tissue Res. 1987;247:259–265. doi: 10.1007/BF00218307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pustovrh G, Snoj A, Sušnik Bajec S. Molecular phylogeny of Salmo of the western Balkans, based upon multiple nuclear loci. Genet Sel Evol. 2014;46:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1297-9686-46-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrlich ST, Rubin RW. Biochemical characterization of crystals from the dermal iridophores of a chameleon Anolis carolinensis. J Cell Biol. 1975;66:635–645. doi: 10.1083/jcb.66.3.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivka U, Halačka K, Sušnik Bajec S. Morphological differences in the skin of marble trout Salmo marmoratus and of brown trout Salmo trutta. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2012;50:255–262. doi: 10.5603/fhc.2012.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaala Ø, Solberg G. Biochemical genetic variability and the taxonomic position of the marmorated trout in River Otra, Norway. Nord J Freshw Res. 1997;73:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi G, Kondo S. Melanophores in the stripes of adult zebrafish do not have the nature to gather, but disperse when they have the space to move. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2008;21:677–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2008.00504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi IK. Electron microscopy of two types of reflecting chromatophores (Iridophores and Leucophores) in the guppy, Lebistes reticulatus Peters. Cell Tissue Res. 1976;173:17–27. doi: 10.1007/BF00219263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi IK, Kajishima T. Fine structure of goldfish xanthophore. J Anat. 1972;112:1–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren AE. Xanthophores in fundulus, with special consideration of their “expanded” and “contracted” phases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1932;18:633–639. doi: 10.1073/pnas.18.11.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, Kondo S. Changing clothes easily: connexin41.8 regulates skin pattern variation. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2012;25:326–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2012.00984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka H, Kondo S. In vitro analysis suggests that difference in cell movement during direct interaction can generate various pigment patterns in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:1867–1872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315416111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka H, Kondo S. Rotating pigment cells exhibit an intrinsic chirality. Genes Cells. 2015;20:29–35. doi: 10.1111/gtc.12194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Zhang X, Gao T, et al. Development and ultrastructure of larval skin in Scophthamus maximus. J Fish China. 2003;27:97–104. [Google Scholar]