Abstract

Objective

To explore outcomes and measures of success that matter most to 'positive outlier' children who improved their body mass index (BMI) despite living in obesogenic neighborhoods.

Methods

We collected residential address and longitudinal height/weight data from electronic health records of 22,657 children ages 6–12 years in Massachusetts. We defined obesity “hotspots” as zip codes where >15% of children had a BMI ≥95th percentile. Using linear mixed effects models, we generated a BMI z-score slope for each child with a history of obesity. We recruited 10–12 year-olds with negative slopes living in hotspots for focus groups. We analyzed group transcripts and discussed emerging themes in iterative meetings using an immersion/crystallization approach.

Results

We reached thematic saturation after 4 focus groups with 21 children. Children identified bullying and negative peer comparisons related to physical appearance, clothing size, and athletic ability as motivating them to achieve a healthier weight, and they measured success as improvement in these domains. Positive relationships with friends and family facilitated both behavior change initiation and maintenance.

Conclusions

The perspectives of positive outlier children can provide insight into children’s motivations leading to successful obesity management. Practice implications: Child/family engagement should guide the development of patient-centered obesity interventions.

Keywords: obesity, overweight, positive deviance, children, attitude to health, qualitative

1. Introduction

Despite a recent leveling off in the rapidly increasing rate of childhood obesity, the high prevalence of children with obesity remains a major public health issue with alarming socioeconomic, racial, and geographic disparities [1]. Promising approaches to address childhood obesity and associated health disparities exist, such as multi-sector strategies that support change at the individual, family, and community levels [2, 3], yet their effectiveness is often limited by the complex social and environmental factors that modify and mediate obesity-related behaviors.

The “positive deviance” or “positive outlier” theoretical approach offers avenues for identifying solutions to public health problems that are highly adaptive to social-environmental context because the strategies emerge from within the context of interest [4]. This strategy seeks to identify individuals who perform better than the majority of their peers on some outcome of interest and applies qualitative exploration to identify the potential mechanisms underlying their success. While prior investigators have studied successful individuals with respect to obesity [5, 6], most studies have taken a quantitative approach to test the predictors of success; yet, it is precisely these a priori assumptions that must be limited in a positive outlier theoretical approach in order to identify unique and novel strategies [7]. We have previously suggested that the positive outlier approach may advance progress in childhood obesity by identifying and learning from successful children and families within obesogenic socio-environmental contexts [8]. We have also applied the approach to examine the perceptions and strategies of parents of positive outlier children who have improved their weight status despite living in neighborhoods with high obesity prevalence [9].

Qualitative methods, particularly focus groups, can be an effective tool for exploratory research among children, with some researchers even finding valuable information from children as young as 4–6 years old [10]. While methodological challenges and ethical considerations must be taken into account when working with children, it is important to acknowledge and include children’s voices when evaluating and addressing the health issues that affect them.

In this study, we sought to explore the perspectives of the positive outlier children themselves. Specifically, we examined the factors that motivated change and the outcomes that mattered most to these successful children. Such patient-centered insight into successful childhood obesity management can be used by health care systems and communities to address childhood obesity in a language and manner that is relevant and accessible to children with obesity and their families.

2. Methods

2.1. Sampling

We recruited focus group participants from among children seen for well-child care at the 14 practices of Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates (HVMA), a multi-specialty group practice in eastern Massachusetts. Using up to 5 years of longitudinal height and weight data from the electronic health records of 22,443 Massachusetts children ages 6 to 12 years-old in February 2013, we used linear mixed effects models and a purposive sampling approach [11] to identify 521 positive outlier children with a negative BMI-z score slope living in obesity hotspots (i.e., zip codes with > 15% prevalence of childhood obesity), as previously described in greater detail [9]. We excluded children with medical problems affecting growth or nutrition documented in their electronic health record problem list or billing record. We calculated BMI as kg/m2 and used participants’ age- and sex-specific BMI percentiles and z-scores. [12] We defined obesity as a BMI percentile ≥95th percentile.

We further limited the recruitment sample to children who were 10–12 years-old at the time of study recruitment in February 2014 (n=193) and had maintained a negative BMI z-score slope through October 2013 (n=174). The study was limited to this age group of children rather than younger children or adolescents, who are distinct in their levels of autonomy over their behaviors and environments.

Among this sample, 12 children’s parents had participated in parent focus groups the prior year and had agreed to be contacted, and two had previously indicated interest in attending parent focus groups but had been unable to attend. The Institutional Review Boards of Partners Health Care approved the study protocol.

2.2. Recruitment and Enrollment

Study staff sent out recruitment letters to the children’s parents explaining the study and providing an opt-out phone number. Two families called the study hotline to opt out. We ranked the remaining 172 children in our recruitment sample by BMI z-score slope. Children with the most negative slopes and parents who participated in previous focus groups were contacted for recruitment first. One week after the letters were mailed, study staff began to contact parents by phone to explain the study, confirm their child’s eligibility, conduct a brief demographic survey, answer questions about the study, and schedule children for focus groups. Staff recruited 6–10 participants for each focus group and discontinued calls upon thematic saturation. Ultimately, all 172 parents were called, 36 participants were recruited, and 21 children attended four focus groups.

2.3. Qualitative Protocol

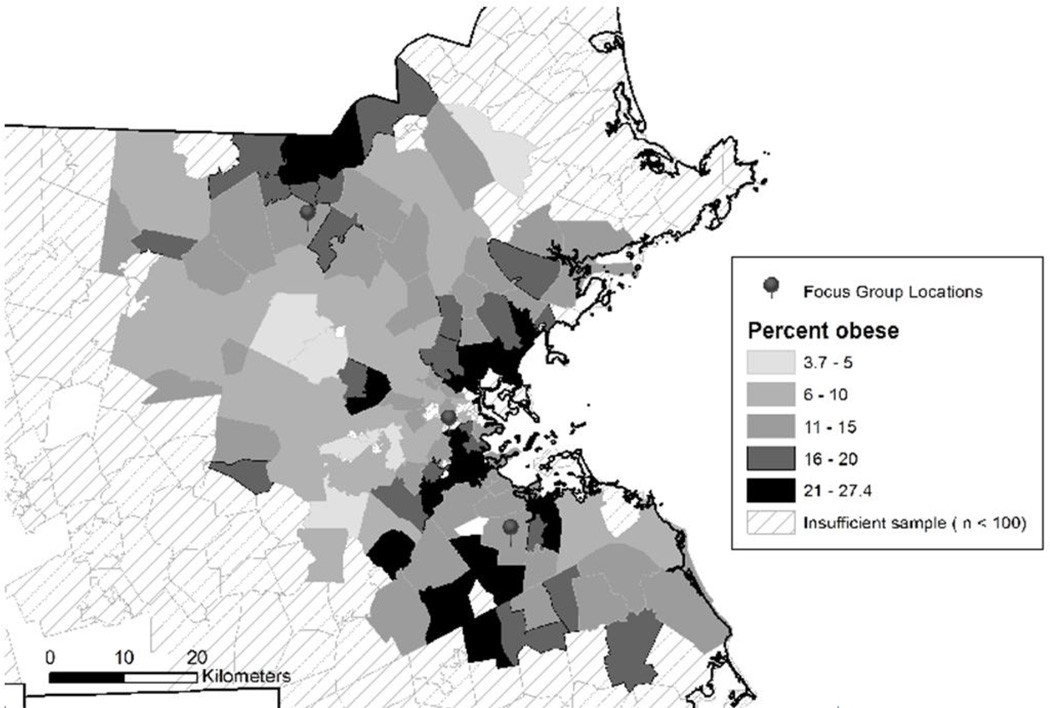

Our study team of pediatricians, health services and public health researchers, and an anthropologist developed a focus group discussion guide (Table 1) through an iterative process. The guide was informed by a review of prior studies exploring child perspectives related to obesity as well as literature describing methodological considerations unique to child focus groups with respect to both structure and content. In particular, we used drawings and activities [13], included breaks [14], minimized age variation within groups, and limited the total time of each group to 90 minutes [15]. The guide was designed using an adaptation of Sorenson’s social contextual model [16] to help identify context and mediating mechanisms around improvement of BMI. Core questions were supplemented with spontaneous follow-up questions during the groups to provide a more robust exploration of relevant topics. We completed four 1.5-hour focus groups at three HVMA locations selected for accessibility to obesity hot spot neighborhoods (Figure 1). We provided participants and their accompanying parents with a light meal and one $50 gift card per participating child as an incentive for participation.

Table 1.

Focus Group Discussion Guide Topics and Sample Questions on Perceptions, Strategies and Suggestions among Positive Outlier Children

| Topic | Discussion Guide Questions |

|---|---|

| Changes in rules/limits |

|

| Changes in physical activity |

|

| Activity 1: Child Reported Outcomes of Interesta |

|

| Activity 2: Facilitators, Barriers, and Potential Intervention Strategiesb |

|

| Activity 3: Child Reported Measures of Successc |

|

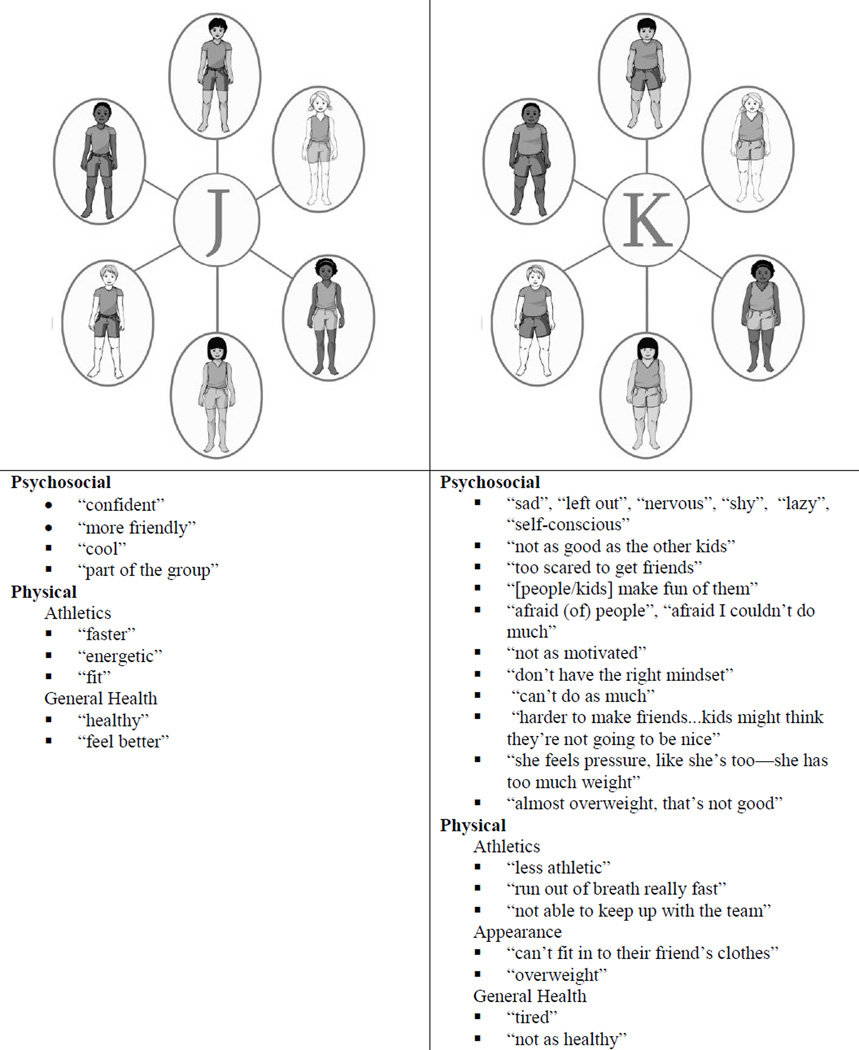

Two illustrations were presented to the children (Figure 2): 6 children with healthy BMIs (labeled J) and the same 6 children with obese BMIs (labeled K).

Each child received another handout (with illustrations of families, the doctor’s office, neighborhoods, and schools) and 10 stickers.

Answers generated in this section were written on a flip chart, and the moderator asked the children to use stickers to vote on the items that would be most important to them.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Childhood Obesity by Zip Code Among 22,443 Massachusetts Children ages 6–12 years-old and Focus Group Locations

The groups were moderated by the project team anthropologist (R.G.), and started with an exploration of rules and limits in the children’s homes around obesity-related behaviors (e.g., sugar-sweetened beverage consumption, screen time, and sleep) and then moved to three activities. In the first activity, children were asked to discuss and compare their projections of the experiences and perceptions of two fictional groups of children in an illustration labeled groups J and K (Figure 2). The images represented different races/ethnicities and genders and the pictures in groups J and K were identical in all ways except weight status. The J image portrayed children with a healthy BMI while the K image portrayed children with obesity. In the second activity, children were given an illustration with 4 quadrants representing family, the doctor’s office, schools, and neighborhoods, and they were asked to place stickers on the domains they thought could help children get to healthier weights; each child received 10 stickers and was instructed that placing more stickers on a domain would mean it was more important. The moderator used the activity to drive discussion around ways in which each domain could serve as a facilitator or barrier to healthful behavior change. In the final activity, we investigated how the children would measure success getting to a healthier weight. The children verbally created a list of successful outcomes and these were recorded by the moderator on a flip chart. Then the children were asked to vote on which outcomes were most important, again using stickers, and then discuss their choices. Both voting exercises were designed to stimulate rich, comparative discussion of key topics rather than to provide quantitative value, although we did record voting outcomes.

Figure 2.

Descriptive Phrases Used by Child Focus Group Participants in Reference to Illustrations of Healthy Weight Children and Children with Obesity

2.4. Piloting

We conducted a pilot focus group with a convenience sample of seven children ages 7–11 years in order to test the feasibility of our planned activities and the age appropriateness of the focus group guide. Based on observations from this pilot focus group, we discovered that the comments and discussion points from the 10 and 11 year-olds were clear, focused, and insightful compared to those of the 7 to 9 year-olds. Children in the younger group had more difficulty staying focused and expressing their thoughts clearly. During the pilot we produced large poster size illustrations for the activities and presented them to the whole group. We found that this resulted in significant peer-pressure and social-desirability bias among participants, particularly during the voting activities. Therefore, for the subsequent groups, we provided individual copies of the illustrations for each child, allowing them to vote individually and then share their thoughts with the group.

2.5. Analysis

The audio recording of each group was sent to an independent company for transcription. After transcription, a group data analysis process was conducted in iterative meetings using an immersion-crystallization approach [17]. This involved repeatedly reading and discussing the transcripts to identify emerging themes and salient topics. The four member analysis team (M.S., G.M., R.G., and C.C.) individually read and took notes on the transcripts before discussing them in team meetings. During these discussions, a list of themes was generated and representative quotes were collected. After we developed this initial list of themes and clarified definitions, the transcript texts were subjected to line-by-line coding using a spreadsheet. The list of themes was modified by team consensus as the need for new themes emerged. Transcripts were once again reviewed individually by the analysis team, and we used the spreadsheet of coded quotations to facilitate further analysis discussions, develop links between themes, finalize data interpretation, and identify representative quotations. Three members of the analysis team attended all of the focus groups in person and added input from their observations and notes from the groups to corroborate theme development and quote selection. Analysis was considered complete when no new themes were generated from transcript review and discussion. Consensus among the analysis team on theme selection and theme organization was used as quality check on data interpretation.

3. Results

We reached thematic saturation after four focus groups with a total of 21 children of diverse race/ethnicity. We determined that had reached data saturation when we began to hear repetitive comments, with few new data and no new themes generated in the final focus groups. The socio-demographic characteristics of children who were recruited (i.e., parent agreed to have the child attend) and children who ultimately participated are similar in all domains (Table 2). In all 4 groups, we noted a dramatic increase in participation and robust discussion among the children with all three activities involving illustrations and voting with stickers. They were clearly more comfortable discussing illustrations of fictional characters than talking about their own experiences.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic Characteristics Reported by the Parents of Positive Outlier Children Recruited for Focus Groups and Focus Group Participants

| Recruited Children N=36 |

Participants N=21 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | Mean (S.D) or N (%) | |

| Positive outlier child age, years | 10.8 (.75) | 10.9 (.73) |

| Relationship to positive outlier child | ||

| Mother | 30 (83%) | 17 (81%) |

| Father | 4 (11%) | 3 (14%) |

| Other Guardian | 2 (6%) | 1 (5%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 4 (11%) | 3 (14%) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 20 (56%) | 10 (48%) |

| Hispanic | 9 (25%) | 6 (29%) |

| Other | 3 (8%) | 2 (10%) |

| Education | ||

| Post-graduate | 7 (19%) | 4 (19%) |

| College graduate | 12 (33%) | 6 (29%) |

| Some College | 13 (36%) | 8 (38%) |

| High School or less | 4 (11%) | 3 (14%) |

| Primary language spoken at home | ||

| English | 29 (81%) | 17 (81%) |

| Spanish | 4 (11%) | 2 (10%) |

| Other | 3 (8%) | 2 (10%) |

| ≥2 children living in the household | 28 (78%) | 19 (90%) |

3.1. Child Reported Motivation for Change

Children described negative psychosocial pressure in different ways, which sometimes served as motivation for change in BMI (Table 3). The children viewed obesity in negative moralistic terms; being at a healthier weight was described as a better state and children perceived obese children as inferior to their normal weight peers in both ability to participate in athletic and social contexts. Representative descriptions of the illustrations comparing healthy weight children to those same children with obesity are shown in Figure 2, with a clear predominance of negative descriptions of children with elevated BMI as opposed to positive descriptions of healthy weight children. All the children, whether by direct statement or nonverbal agreement, expressed that bullying was a major issue for obese children, and some specifically articulated this as motivation for getting to a healthier weight. The children identified authority figures, such as doctors or parents, as providing motivation to change behaviors.

Table 3.

Themes and Representative Quotes for Patient-Reported Motivation for Change

| Motivation for Change: Social Pressure |

Illustrative Quotations |

|---|---|

| Negative perceptions of obesity |

|

| Peer comparisons |

|

| Avoiding Bullying/Teasing |

|

| Authority figures (Doctor/Parent) |

|

3.2. Child Reported Influences on Initiation and Maintenance of Behavior Change

Relationships with peers and family dominated the children’s descriptions of influences on initiation and maintenance of healthful behavior change (Table 4). According to the children, peer engagement served as a key facilitator to improved health, with some reporting collaboration with overweight friends to get to a healthier weight and others noting that their healthy weight friends were supportive. Additionally, children said that healthy weight children served as models. The children stated that simply having fun was a positive influence, especially in reference to participating with peers in physical activity.

Table 4.

Topics, Themes, and Representative Quotes for Key Influences on the Initiation and Maintenance of Healthy Behavior Change

| Influences on Initiation of Change and Maintenance: Key Relationships, Schools and the Neighborhood |

Illustrative Quotations |

|---|---|

| Peers | |

|

|

|

|

| Family | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Doctor’s office | |

|

|

|

|

| Neighborhoods | |

|

|

|

|

| Technology | |

|

|

|

|

The children discussed family as a positive influence through imposed limits and rules around eating, providing guidance and support, or implementing family level change by modifying shopping and family diet and physical activity. Children also said that parents could be a negative influence by providing unhealthy food at home or lacking knowledge regarding healthy choices. Children described doctors as an expert source of information about how to be healthier, while emphasizing that doctors needed to be direct and serious when talking about weight as opposed to “sugar-coating it.”

In considering the role of neighborhoods, children discussed both positive features supporting healthy behavior change, such as grocery stores, parks, and gyms, as well as negative features such as unhealthy food options in convenience stores and the lack of safe areas to be physically active. Children described schools in similarly contrasting terms, with gym classes, team sports, and school nurses being positive influences and bullying and poor lunches being negative factors. Technology was mentioned by children as providing an opportunity to exercise in the home through video game systems, and some children said that they used apps to track their exercise and dietary intake.

3.3. Child Reported Measures of Success

Children measured success getting to healthier weight in both concrete and abstract ways (Table 5). Many children focused on progress in athletic performance and being able to wear preferred styles and age-appropriate sizes of clothing. Several described taking pride in overcoming challenges and reaching a difficult goal, noting that behavior change was hard at first but got easier over time. The children also very frequently discussed social outcomes such as fitting in with their peers and avoiding weight-related stigmatization and bullying.

Table 5.

Themes and Representative Quotes for Patient-Reported Measures of Success

| Measures of Success: Sense of Progress |

Representative Quotations |

|---|---|

| Emotional |

|

| Appearance |

|

| Social |

|

| Physical Fitness |

|

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Discussion

In this qualitative study of 10 to 12 year-old positive outlier children who successfully improved their BMI despite living in obesogenic neighborhoods, we explored ways that children perceived and measured success in obesity management as well as potential contributors to that success. Overall, peer and family support proved to be critical influences on the initiation and maintenance of weight-related behavior change. Children were motivated to improve their BMI by negative psychosocial pressure including fear of bullying and negative views of obesity from their peers and themselves. Children measured success getting to a healthier weight by tracking their progress in both abstract ways such as fitting in socially, and concrete ways such as improved athletic performance. Psychosocial pressure, both positive and negative, was ubiquitous and presented itself as a meta-theme.

The positive outlier approach has been used to study adult obesity [7] and childhood obesity from the perspective of parents [9]. We believe, however, that this is the first study utilizing a positive outlier approach to explore the perspectives of children with respect to obesity. Children with obesity and their families live within complex socio-environmental contexts that include elements impacting energy intake and expenditure but that are often beyond their control and not easily modified. In this study, we specifically sought to identify the strategies and perceptions of successful children that helped them surmount potentially challenging aspects of living in neighborhoods with high obesity prevalence.

Among the positive outlier children in this study, family and peer support were critical and potentially modifiable facilitators of success. While social support from parents, siblings, and peers has been extensively studied as a predictor of physical activity participation [18–20] and dietary behavior change [21, 22], our findings lend support to mounting evidence that children’s family and social networks can be leveraged to cultivate and reinforce improvements in weight status [23, 24]. The social learning theory stresses that individuals learn their behavior and new skills from observing others, termed modeling [25]. Our findings also suggest that positive outlier children may learn to make healthful behavior changes through observation and modeling of influential and respected characters in their lives, including parents and peers. This process of learning may also be enhanced by a dynamic interaction with intrapersonal factors such as wanting to fit in and not be bullied. A comprehensive understanding of these social learning and interpersonal factors may help inform the design of effective interventions to improve childhood BMI.

One notable feature of the positive outlier children in our study was that they measured their success by tracking their progress socially and physically. Several other studies have shown that obese children experience bullying, social stigma, and exercise intolerance [26]. The results of our study corroborate these findings, as well as that these challenges, which are commonly present in the lives of children with obesity, are mitigated by improving BMI. It follows that bullying, social stigma, and exercise intolerance could be considered symptoms of childhood obesity which are ameliorated as the disease declines. Our findings suggest that these are also the symptoms that matter most to children who have achieved a healthier weight. Resolution of these symptoms was described by our participants as the most meaningful outcome of improved BMI. Emphasizing these outcomes to both children and their parents in family-centered obesity interventions may help to secure higher levels of engagement and buy-in from families to effect behavior change.

Furthermore, the ubiquity of negative social pressure and bullying in the experience of the children in our focus groups was perhaps most clear in the ways in which the children described the illustrations of healthy weight children and children with obesity. This observation highlights the imperative for interventions targeting obesity to acknowledge and address social and emotional well-being [27, 28].

Strengths of the study design included carefully considered eligibility criteria utilizing longitudinal, objective growth data from electronic health records and mixed effects linear regression modeling to purposively define the recruitment sample of positive outlier children living in obesity hot spot zip codes. The moderator’s guide and analysis process were informed by a theoretical framework, and combined with a positive outlier approach which seeks to limit a priori assumptions. The content analysis of participants’ statements was conducted by a group of researchers with varying perspectives and backgrounds. The study also has a few limitations. First, it is possible that children who participated in the groups could have more motivated families which could have biased our findings. Second, our sample population represents insured, English-speaking patients presenting routinely for well child visits, and the parents of participants reported relatively high education levels compared to state and national census reports [29]. Findings may have differed had our study population been of lower socio-economic status and non-English speakers. Parental education has been linked to child obesity [30] and could play a role in mediating positive outlier status, yet our study is not designed or equipped to examine this hypothesis. Further, the educational attainment reported by the parents of participants is comparable to past studies among overweight and obese children at the same HVMA practices so it does not appear that these parents of positive outliers were more highly educated that other HVMA parents [31]. Third, as is the nature of qualitative research, our results are not intended to be generalizable or to determine percentages of children holding a given belief, but rather we aimed to explore concepts and stimulate hypotheses to guide the development of childhood obesity interventions. Nonetheless, themes repeatedly emerged across multiple groups, which supports their salience in this study population.

4.2. Conclusion

Children who successfully improved their BMI despite living in neighborhoods with high obesity prevalence focused on psychosocial and physical obesity-related symptoms as outcomes of interest, and they tracked improvement in these domains to measure their success. Social support from parents, families, and peers was a dominant facilitator of success in achieving healthy behavior change.

4.3. Practice Implications

These finding can be used to design and test patient and family-centered childhood obesity interventions that better address the outcomes that matter most to children and measure success in a relevant and accessible way. The perceptions and experiences of the children in this study could be used to aid and encourage other children with expressing their concerns and preferences and allow care providers to center discussions about weight on the specific outcomes that are most relevant to patients and families. Doing so may enhance patient and family engagement and in turn optimize intervention success. Such interventions should also consider the influence of interpersonal factors on the motivation to change behavior and leverage the influence of social networks and support. Finally, the management of obesity in children would be incomplete without a careful approach to fostering social and emotional well-being. Interventions should include measures of quality of life and social and emotional health in evaluating intervention success.

Highlights.

We conducted focus groups with children identified as obesity positive outliers.

We defined positive outliers using longitudinal growth and obesity prevalence data.

We present weight-related outcomes most salient to this purposive sample of children.

Children focused on bullying, physical appearance, clothing size and athleticism.

These findings can guide more effective, patient-centered obesity interventions.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Chompunut Ditchaiwong for developing the illustrations, Sheryl L Rifas-Shiman and Renata Koziol Smith for data analysis, and the children who participated in the pilot group and study groups as well as their parents.

Funding Sources: This study was supported through a Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (IH-1304-6739) and by Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award UL1 TR001102) and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers. Dr. Sharifi is supported by an AHRQ Mentored Career Development Award for Child and Family Centered Outcomes Research (1 K12 HS 022986-01). All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee, Harvard Catalyst, Harvard UniversityHarvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers, or the National Institutes of Health. These sponsors played no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999–2010. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307:483–490. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang TT, Drewnosksi A, Kumanyika S, Glass TA. A systems-oriented multilevel framework for addressing obesity in the 21st century. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6:A82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swinburn B, Egger G, Raza F. Dissecting obesogenic environments: the development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity. Prev Med. 1999;29:563–570. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Ramanadhan S, Rowe L, Nembhard IM, Krumholz HM. Research in action: using positive deviance to improve quality of health care. Implement Sci. 2009;4:25. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raynor HA, Jeffery RW, Phelan S, Hill JO, Wing RR. Amount of food group variety consumed in the diet and long-term weight loss maintenance. Obes Res. 2005;13:883–890. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butryn ML, Phelan S, Hill JO, Wing RR. Consistent self-monitoring of weight: a key component of successful weight loss maintenance. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:3091–3096. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stuckey HL, Boan J, Kraschnewski JL, Miller-Day M, Lehman EB, Sciamanna CN. Using positive deviance for determining successful weight-control practices. Qual Health Res. 2011;21:563–579. doi: 10.1177/1049732310386623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharifi M, Marshall G, Marshall R, Bottino C, Goldman R, Sequist T, et al. Accelerating progress in reducing childhood obesity disparities: exploring best practices of positive outliers. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24:193–199. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharifi M, Marshall G, Goldman R, Rifas-Shiman S, Horan C, Koziol R, et al. Exploring Innovative Approaches and Patient-Centered Outcomes from Positive Outliers in Childhood Obesity. Acad Pediatr. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.08.001. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heary CM, Hennessy E. The use of focus group interviews in pediatric health care research. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27:47–57. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devers KJ, Frankel RM. Study design in qualitative research--2: Sampling and data collection strategies. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2000;13:263–271. doi: 10.1080/13576280050074543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Mei Z, et al. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital and health statistics Series 11, Data from the national health survey. 2002:1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fargas-Malet M, McSherry D, Larkin E, Robinson C. Research with children: methodological issues and innovative techniques. Journal of Early Childhood Research. 2010;8:175–192. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibson F. Conducting focus groups with children and young people: strategies for success. Journal of Research in Nursing. 2007;12:473–483. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgan M, Gibbs S, Maxwell K, Britten N. Hearing children's voices: methodological issues in conducting focus groups with children aged 7–11 years. Qualitative Research. 2002;2:5–20. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sorensen G, Barbeau E, Hunt MK, Emmons K. Reducing social disparities in tobacco use: a social-contextual model for reducing tobacco use among blue-collar workers. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:230–239. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borkan J. Immersion/crystallization. In: Crabtree B, Miller W, editors. Doing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beets MW, Cardinal BJ, Alderman BL. Parental Social Support and the Physical Activity–Related Behaviors of Youth: A Review. Health Educ Behav. 2010 doi: 10.1177/1090198110363884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mendonça G, Cheng LA, Mélo EN, de Farias Júnior JC. Physical activity and social support in adolescents: a systematic review. Health Educ Res. 2014 doi: 10.1093/her/cyu017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cleland V, Timperio A, Salmon J, Hume C, Telford A, Crawford D. A Longitudinal Study of the Family Physical Activity Environment and Physical Activity Among Youth. Am J Health Promot. 2010;25:159–167. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.090303-QUAN-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cutler GJ, Flood A, Hannan P, Neumark-Sztainer D. Multiple Sociodemographic and Socioenvironmental Characteristics Are Correlated with Major Patterns of Dietary Intake in Adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:230–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salvy S-J, de la Haye K, Bowker JC, Hermans RCJ. Influence of peers and friends on children's and adolescents' eating and activity behaviors. Physiol Behav. 2012;106:369–378. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li JS, Barnett TA, Goodman E, Wasserman RC, Kemper AR. Approaches to the Prevention and Management of Childhood Obesity: The Role of Social Networks and the Use of Social Media and Related Electronic Technologies: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:260–267. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182756d8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shin H-S, Valente TW, Riggs NR, Huh J, Spruijt-Metz D, Chou C-P, et al. The interaction of social networks and child obesity prevention program effects: The pathways trial. Obesity. 2014;22:1520–1526. doi: 10.1002/oby.20731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hammer T. Social Learning Theory. In: Goldstein S, Naglieri J, editors. Encyclopedia of Child Behavior and Development. Springer US; 2011. pp. 1396–1397. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lachal J, Orri M, Speranza M, Falissard B, Lefevre H, Moro MR, et al. Qualitative studies among obese children and adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2013;14:351–368. doi: 10.1111/obr.12010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Russell-Mayhew S, McVey G, Bardick A, Ireland A. Mental Health, Wellness, and Childhood Overweight/Obesity. Journal of Obesity. 2012;2012:9. doi: 10.1155/2012/281801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lumeng JC, Forrest P, Appugliese DP, Kaciroti N, Corwyn RF, Bradley RH. Weight Status as a Predictor of Being Bullied in Third Through Sixth Grades. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e1301–e1307. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.United States Census Bureau. State & County QuickFacts, Massachusetts. [Accessed July 9, 2014]; Available at: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/25000.html.

- 30.Singh GK, Siahpush M, Kogan MD. Rising social inequalities in US childhood obesity, 2003–2007. Annals of epidemiology. 2010;20:40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taveras EM, Gortmaker SL, Hohman KH, Horan CM, Kleinman KP, Mitchell K, et al. Randomized controlled trial to improve primary care to prevent and manage childhood obesity: the High Five for Kids study. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2011;165:714–722. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]