Abstract

Background

Computed tomographic (CT) characteristics derived from noninvasive images that represent the entire tumor may have diagnostic and prognostic value. The purpose of this study was to assess the association of a standardized set of semiquantitative CT characteristics of lung adenocarcinoma with overall survival.

Patients and Methods

An initial set of CT descriptors was developed to semiquantitatively assess lung adenocarcinoma in patients (n=117) who underwent resection. Survival analyses were used to determine the association between each characteristic and overall survival. Principle component analysis (PCA) was used to determine characteristics that may differentiate histological subtypes.

Results

Characteristics significantly associated with overall survival included pleural attachment (p < 0.001), air bronchogram (p = 0.03), and lymphadenopathy (p = 0.02). Multivariate analyses revealed pleural attachment was significantly associated with an increased risk of death overall (hazard ratio [HR] = 3.21; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.53 – 6.70) and among patients with lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas (HR = 5.85; 95% CI 1.75 – 19.59), while lymphadenopathy was significantly associated with an increased risk of death among patients with adenocarcinomas without a predominant lepidic component (HR = 3.07; 95% CI 1.09 – 8.70). A PCA model showed that texture (ground-glass opacity component) was most important for separating the two subtypes.

Conclusion

A subset of the semiquantitative characteristics described herein has prognostic importance and ability to distinguish between different histological subtypes of lung adenocarcinoma.

Keywords: Semiquantitative, Computed tomography, Lung adenocarcinoma, Lepidic growth, Prognosis

Introduction

Adenocarcinoma of the lung is a major cause of cancer-related morbidity and mortality worldwide 1, and its incidence has been increasing over the last several decades 2, 3. Histological characteristics obtained from relatively small portion of tumor may not be representative of the entire tumor, although histological characteristics and staging are commonly used to determine treatment, intra-tumoral heterogeneity can be a limiting factor to predict prognosis and treatment response. Thus, characteristics derived from analyses of radiological images that represent the entire tumor may have diagnostic and prognostic value. Specifically, imaging features that are associated with the underlying tumor biology could have clinical translational implications. For example, in contrast to solid- or micropapillary-predominant adenocarcinoma, lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma could eventually be treated with optimized tissue-sparing resection due to the much better outcome and the scarcity of nodal metastases in this subtype 4.

Medical imaging can provide noninvasive measurements of tumor features. However, current radiological practice is generally qualitative and provides only limited quantitative information such as dimensional measurements of tumor size. Efforts have been made to develop a standardized lexicon for describing lung tumor features and a standard method for converting these descriptors into quantitative, mineable data with the intent of discovering their associations with patient survival 5-7. Computational technical development has permitted a high-throughput process in which a large number of shape, edge, and texture imaging features are extracted 8, 9. However, computerized algorithms are more highly dependent on harmonized acquisition and reconstruction parameters than are human readers. The environment of the tumor, which includes important prognostic information, such as desmoplastic response, vascular supply or localized infiltration of the tumor cannot be segmented effectively to date. Therefore, computational analysis is not yet able to replace the trained eyes of a radiologist. Nevertheless, computer-derived features can aid radiological diagnosis by extracting quantitative and unbiased features. Computationally-derived imaging features have been developed to annotate radiological observations 10, 11, and the expertise of radiologist can provide guidance for automated approaches to develop the imaging features that have clinical relevance. Thus, we hypothesized that a standardized set of semiquantitative imaging features can predict prognosis of the patients and benefit the development of prognostic-relevant computerized features.

The purpose of this study was to develop and test a standardized set of semiquantitative computed tomography (CT) descriptors of lung adenocarcinoma and assess their association with overall survival. This approach has the potential to support automated analyses by providing guidance and expert evaluation of necessary imaging characteristics, and it can ultimately be used to develop decision support clinical tools to increase accuracy and efficiency of radiological diagnosis.

Patients and Methods

Study Population

The institutional review board approved this retrospective study and waived the informed consent requirement. Data were collected and handled in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. This study included 117 patients diagnosed with histologically confirmed adenocarcinoma of the lung who had surgery for primary lung cancer in our institution between January 2006 and June 2009. The mean age of the patients was 65.1± 7.5 years, 93.3% self-reported race as white, 55.2% were female, 90.5% were ever-smokers, and 47% had stage I lung cancer. According to their growth pattern, we classified tumors into two subtypes as previous studies 12-14: (1) lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas (n=55), and (2) adenocarcinomas without a predominant lepidic growth (n=62), among these cases, 11 had a small proportion of a lepidic component. Lepidic growth pattern was defined as involving alveolar septa with a relative lack of acinar filling. In terms of the new multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma sponsored by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society in 2011 15, our subtype of lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas included adenocarcinoma in situ, minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, and lepidic predominant invasive adenocarcinoma.

CT Imaging and Analyses

All CT scans were performed prior to surgery. Ninety-five patients underwent contrast-enhanced CT and 22 patients had non-enhanced CT.

A clinical radiologist with 7 years of experience in chest CT diagnosis developed 25 descriptors and subsequently reviewed all of the CT images. The goal was to develop an initial set of descriptors covering a broad area of characteristics with as much resolution as possible. As shown in Table 1, these descriptors were classified into three categories: (1) measures describing the tumor (n=16); (2) measures describing the surrounding tissue (n=5); and (3) measures describing associated findings (n=4). Among these descriptors, 17 were rated using a 1-5 ordinal scale and 8 descriptors were binary categorical variables. Examples of CT images for each scale of characteristics are shown in Figure S1.

Table 1.

Distribution and lexicon of the CT imaging characteristics

| CT characteristic | N(%) | Definition | Scoring definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor | |||

| Space Localization | |||

| Location | Lobe location of the tumor | ||

| 1 | 35(29.9) | 1-right upper lobe | |

| 2 | 9(7.7) | 2-right middle lobe | |

| 3 | 20(17.1) | 3-right lower lobe | |

| 4 | 37(31.6) | 4-left upper lobe | |

| 5 | 16(13.7) | 5-left lower lobe | |

| Distribution | Central location: tumor located in the segmental or more proximal bronchi; Peripheral location: tumor located in the subsegmental bronchi or more distal airway | ||

| 0 | 9(7.7) | 0-central | |

| 1 | 108(92.3) | 1-peripheral | |

| Fissure attachment | Tumor abuts the fissure, tumor's margin is obscured by the fissure | ||

| 0 | 81(69.2) | 0-no | |

| 1 | 36(30.8) | 1-yes | |

| Pleural attachment | |||

| 0 | 82(70.1) | 0-no | |

| 1 | 35(29.9) | 1-yes | |

| Size | The greatest dimension in lung window | ||

| 1 | 29(24.8)1 | 1-≤ 2 cm | |

| 2 | 46(39.3) | 2-> 2 & ≤ 3 cm | |

| 3 | 35(29.9) | 3-> 3 & ≤ 5 cm | |

| 4 | 7(6.0) | 4-> 5 & ≤ 7 cm | |

| 5 | 0 | 5->7 cm | |

| Shape | |||

| Sphericity | Roundness | ||

| 1 | 7(6.0) | 1-round | |

| 2 | 18(15.4) | ||

| 3 | 65(55.6) | 2,3,4,5–elongated with increasing degrees | |

| 4 | 24(20.5) | ||

| 5 | 3(2.6) | ||

| Lobulation | Contours with undulations | ||

| 1 | 3(2.6) | 1-none | |

| 2 | 34(29.1) | ||

| 3 | 48(41.0) | 2,3,4,5-lobulated with increasing degrees | |

| 4 | 28(23.9) | ||

| 5 | 4(3.4) | ||

| Concavity | Concave cuts | ||

| 1 | 6(5.1) | 1-none | |

| 2 | 37(31.6) | ||

| 3 | 38(32.5) | 2,3,4,5–concaved with increasing degrees | |

| 4 | 28(23.9) | ||

| 5 | 8(6.8) | ||

| Irregularity | Complex shape | ||

| 1 | 0 | 1-smooth | |

| 2 | 22(18.8) | ||

| 3 | 44(37.6) | 2,3,4,5–irregular with increasing degrees | |

| 4 | 34(29.1) | ||

| 5 | 17(14.5) | ||

| Margin | |||

| Border definition | Well or ill-defined border | ||

| 1 | 2(1.7) | 1-well defined | |

| 2 | 50(42.7) | 2,3,4,5-poorly defined with increasing degrees | |

| 3 | 40(34.2) | ||

| 4 | 17(14.5) | ||

| 5 | 8(6.8) | ||

| Spiculation | Lines radiating from the margins of the tumor | ||

| 1 | 6(5.1) | 1-none | |

| 2 | 46(39.3) | ||

| 3 | 33(28.2) | 2,3,4,5- spiculated with increasing degrees | |

| 4 | 26(22.2) | ||

| 5 | 6(5.1) | ||

| Density | |||

| Texture | Solid or ground-glass opacity | ||

| 1 | 3(2.6) | 1-Nonsolid (pure ground-glass opacity) | |

| 2 | 18(15.4) | 2-Partly solid, small extent of solid component | |

| 3 | 35(29.9) | 3-Partly solid, large extent of solid component | |

| 4 | 30(25.6) | 4-solid, with relatively low density | |

| 5 | 31(26.5) | 5-solid | |

| Air space | Including cavity and pseudocavity due to the difficulty to differentiate on CT images | ||

| 1 | 65(55.6) | 1-None | |

| 2 | 30(25.6) | ||

| 3 | 16(13.7) | 2,3,4,5-from small to large extent of lucencies | |

| 4 | 5(4.3) | ||

| 5 | 1(0.9) | ||

| Air bronchogram | Tubelike or branched air structure within the tumor | ||

| 1 | 75(64.1) | 1-None | |

| 2 | 26(22.2) | ||

| 3 | 8(6.8) | 2,3,4,5-from small to large extent of air bronchogram | |

| 4 | 6(5.1) | ||

| 5 | 2(1.7) | ||

| Enhancement heterogeneity | Heterogeneity of tumor on contrast-enhanced images | ||

| 1 | 2(1.7) | 1-homogeneous | |

| 2 | 10(8.6) | ||

| 3 | 34(29.1) | 2,3,4,5-from mildly to highly heterogeneous | |

| 4 | 28(23.9) | ||

| 5 | 18(15.4) | ||

| N/A | 25(21.4) | ||

| Calcification | Any patterns of calcification in the tumor | ||

| 0 | 111(94.9) | 0-no | |

| 1 | 6(5.1) | 1-yes | |

| Surrounding tissues | |||

| Pleural retraction | Retraction of the pleura towards the tumor | ||

| 1 | 12(10.3) | 1-none | |

| 2 | 34(29.1) | ||

| 3 | 42(35.9) | 2,3,4,5- from slight to obvious pleural retraction | |

| 4 | 26(22.2) | ||

| 5 | 3(2.6) | ||

| Vascular convergence | Convergence of vessels to the tumor, only applied to the peripheral tumors | ||

| 1 | 23(19.7) | 1-none | |

| 2 | 35(29.9) | 2,3,4,5- from slight to obvious vascular convergence | |

| 3 | 22(18.8) | ||

| 4 | 24(20.5) | ||

| 5 | 6(5.1) | ||

| N/A | 7(6.0) | ||

| Thickened adjacent bronchovascular bundle | Widening of adjacent bronchovascular bundle | ||

| 1 | 83(70.9) | 1-none | |

| 2 | 15(12.8) | ||

| 3 | 17(14.5) | 2,3,4,5- from slightly to obviously thickened | |

| 4 | 1(0.9) | ||

| 5 | 1(0.9) | ||

| Emphysema periphery | Peripheral emphysema caused by the tumor or preexisting emphysema | ||

| 1 | 52(44.4) | 1-none | |

| 2 | 25(21.4) | ||

| 3 | 28(23.9) | 2,3,4,5-from mild to severe emphysema | |

| 4 | 9(7.7) | ||

| 5 | 3(2.6) | ||

| Fibrosis periphery | Peripheral fibrosis caused by the tumor or preexisting fibrosis | ||

| 1 | 7(6.0) | 1-none | |

| 2 | 27(23.1) | ||

| 3 | 50(42.7) | 2,3,4,5-from mild to severe fibrosis | |

| 4 | 26(22.2) | ||

| 5 | 7(6.0) | ||

| Associated findings | |||

| Nodules in primary tumor lobe | Any nodules suspected malignant or indeterminate | ||

| 0 | 60(51.3) | 0-no | |

| 1 | 57(48.7) | 1-yes | |

| Nodules in non-tumor lobes | Any nodules suspected malignant or indeterminate | ||

| 0 | 45(38.5) | 0-no | |

| 1 | 72(61.5) | 1-yes | |

| Lymphadenopathy | Thoracic lymph nodes with short axis greater than 1 cm | ||

| 0 | 83(70.9) | 0-no | |

| 1 | 34(29.1) | 1-yes | |

| Vascular involvement | Vessels narrowed, occluded or encased by the tumor, only applied to the contrast-enhanced images | ||

| 0 | 33(28.2) | 0-no | |

| 1 | 61(52.1) | 1-yes | |

| N/A | 23(19.7) |

None of the long axis tumor sizes were smaller than 1.02 cm

Our set of descriptors was adapted in part from the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) of the American College of Radiology 16, 17, although differences exist between degree (e.g. we used 5 levels compared to 2) and organ-specific descriptions. We also adapted measures from the lexicon of the Fleischner Society 18 that captured lung cancer features. Other descriptors were adapted from the literature 19, 20. In particular, we combined “cavity” and “pseudocavity” used by Fleischner Society into “air space” as Matsuki et al 20 did because of the difficulty to differentiate them on CT images. The tumor size was measured in the long axis and then classified according to new 7th lung cancer TNM classification and staging system, which has 5 size-based categories with cut-off points at 2, 3, 5 and 7 cm 21.

Each tumor was rated by assessing all slices and reporting with a standardized scoring sheet. A second radiologist, with 5 years of experience in chest CT diagnosis, then independently rated the cases using the scoring sheet after training.

Statistical Analyses

The agreement between the two readers was measured by Kappa for binary variable or Weighted Kappa index for ordinal variable. The kappa value was interpreted as follows: <0: poor agreement; 0 – 0.2: slight agreement; 0.2 – 0.4: fair agreement; 0.4 – 0.6: moderate agreement; 0.6 – 0.8: substantial agreement; > 0.8: almost perfect agreement 22.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves with the log-rank test were performed using R version 2.14 (R Project for Statistical Computing, http://www.r-project.org) and multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression was performed using Stata/MP 12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Among characteristics that were found to be statistically significantly associated with overall survival in univariate analyses, we utilized reverse selection methods to model which sets of CT characteristics were associated with overall survival. Standard clinical risk factors, including age, race, gender, smoking status, histological subtype, long axis tumor size (cm), and clinical stage, were incorporated into the modeling where appropriate. We also performed Classification and Regression Tree (CART) adapted for failure time data that used the martingale residuals of a Cox model to approximate chi-square values for all possible cut-points for the characteristics (http://econpapers.repec.org/software/bocbocode/s456776.htm). The false discovery rate (FDR) was utilized to account for multiple testing. The prior for a feature with a FDR ≤ 0.25 is regarded as modest confidence that the association is unlikely to represent a false-positive result and a feature with a FDR ≤0.05 is regarded as high confidence that the association is unlikely to represent a false-positive result.

Principle component analysis (PCA) was performed using Evince V2.5.5 (UmBio AB, Umeå, Sweden) to determine characteristics that may differentiate histological subtypes. PCA is a technique that reduces a high-dimensional dataset to a low-dimensional dataset while retaining most of the variation in the data 23. The new low-dimensional dataset is created by the PCA-derived principal components also called scores. These are a linear combination of all variables, where the loadings describe the importance of the original variable for each principal component. The first principal component describes most of the variance and is often considered the most important principal component, while the following principal components show a decreasing amount of explained variance. The results of a PCA models are frequently visualized in score and loading plots. The score plot is related to the samples and shows which samples are similar to each other, groupings between classes of samples and also outliers. The loading plot shows which variables are important for the results seen in the score plot and also which variables are similar to each other. Each variable was normalized to unit variance prior to PCA.

Results

Reader Reproducibility

All cases (n=117) were independently read by two radiologists. The agreement of the two readers, as measured by the kappa value, ranged between 0.68-1.00. Lobulation, concavity, pleural retraction, fibrosis periphery, and nodules in nontumor lobes had substantial agreement and all other characteristics had almost perfect agreement (Table S1).

Semiquantitative CT Characteristics and Overall Survival

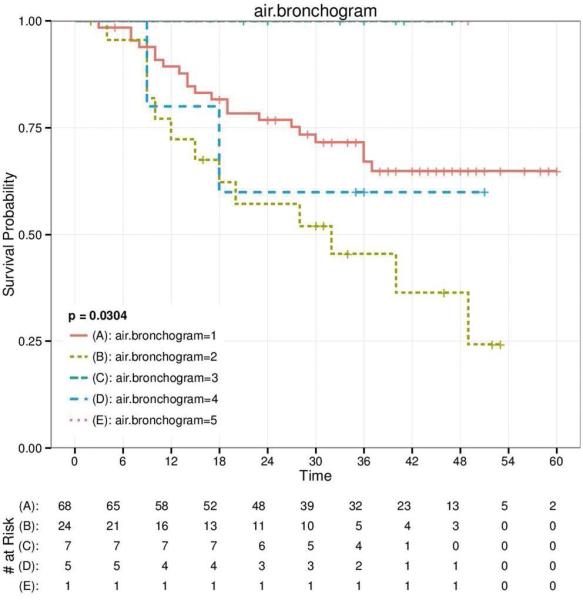

CT imaging data were available on 117 patients (Table 1) but complete survival data were only available for 105 patients. The range of the tumor size was 1.02 cm to 6.72 cm (2.89±1.22 cm). Based on the distributions in Table1, we analyzed the association of each of the 25 characteristics with overall survival (Figures 1 and 2 and Figure S2). The characteristics that were statistically significantly associated with overall survival (Figure 1) were pleural attachment (p < 0.001), air bronchogram (p = 0.03), and lymphadenopathy (p = 0.02). Size, lobulation, and thickened adjacent bronchovascular bundle were also significantly associated with overall survival (p < 0.05), yet the associations were likely driven by small numbers in the distribution of the descriptors. This can be observed in Figure 2, where the extremes of the characteristic distributions represented the poorer survival groups. FDR revealed with high confidence that the association between pleural attachment and overall survival (FDR = 0.022) was unlikely to represent a false-positive result. FDR revealed with modest confidence that the associations of air bronchogram (FDR = 0.213) and lymphadenopathy (FDR = 0.212) with overall were unlikely to represent a false-positive result.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for pleural attachment (A), air bronchogram (B), and lymphadenopathy (C) of all adenocarcinomas, which are statistically significantly associated with overall survival.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for size (A), lobulation (B), and thickened adjacent bronchovascular bundle (C) of all adenocarcinomas, which are suggestive to be associated with overall survival.

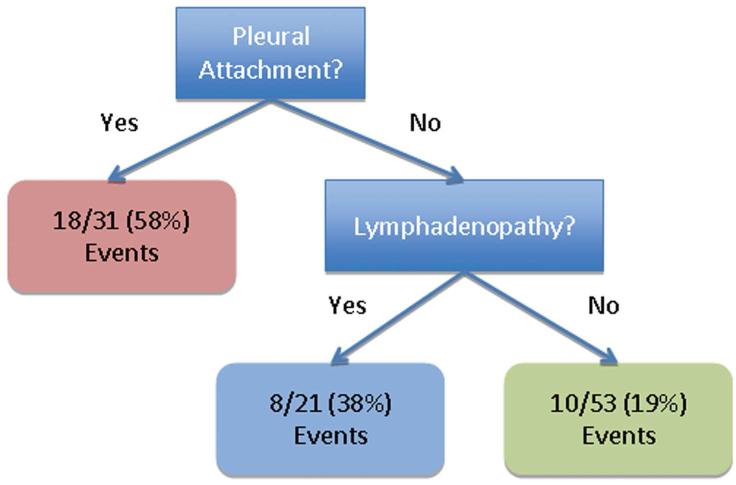

As shown in Table 2, for the multivariable Cox proportional hazard models we first determined the main effects for pleural attachment, air bronchogram, and lymphadenopathy, and then stratified the data by histological subtype. Pleural attachment (HR = 3.21; 95% CI 1.53 – 6.70) was statistically significantly associated with an increased risk of death among all patients and among patients with lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas (HR = 5.85; 95% CI 1.75 – 19.59). For patients with adenocarcinomas without a predominant lepidic growth, lymphadenopathy was associated with an increased risk of death (HR = 3.07; 95% CI 1.09 – 8.70). A reverse stepwise selection approach revealed similar findings to our main effects analyses. When we performed a CART analysis (Figure 3) for pleural attachment, air bronchogram, and lymphadenopathy, we found that patients without pleural attachment and without lymphadenopathy had significantly improved survival compared to patients with pleural attachment (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Hazard ratios for the association between the CT characteristics and overall survival

| Overall |

Subtype 1c |

Subtype 2c |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| mHR (95% CI)a | mHR (95% CI)a | mHR (95% CI)a | |

| Main effects | |||

| Pleural attachment | 3.21 (1.53 – 6.70) | 5.85 (1.75 – 19.59) | 1.83 (0.61 – 5.52) |

| Air bronchogram | 1.21 (0.58 – 2.54) | 0.99 (0.28 – 3.55) | 1.18 (0.44 – 6.18) |

| Lymphadenopathy | 1.89 (0.91 – 3.92) | 0.48 (0.05 – 4.53) | 3.07 (1.09 – 8.70) |

| Final Modelb | |||

| Pleural attachment | 3.40 (1.57 – 7.40) | 5.86 (1.75 – 19.59) | NI |

| Air bronchogram | NI | NI | NI |

| Lymphadenopathy | 1.97 (0.92 – 4.21) | NI | 3.07 (1.09 – 8.71) |

Bolded values indicate a statistically significant result

Adjusted for age, race, gender, smoking status, histological subtype, long axis tumor size (cm), and stage, where appropriate

The final models were derived from reverse stepwise regression modeling with a 0.1 significance level for inclusion into the model. Adjustment factors were forced into the reverse stepwise selection model. The features that were not included in the final model were designated as ‘NI’

Subtype 1 is lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas; Subtype 2 is adenocarcinomas without a predominant lepidic component

Figure 3.

Decision tree (A) and Kaplan–Meier survival curves (B) based on CART analyses for the three statistically significant characteristics in Figure 1.

Difference between the Characteristics of Histological Subtypes

PCA analysis of the imaging characteristics identified two principal components explaining 14% and 11% (totally 25%) of the variance. These two principal components demonstrated that the two subtypes (lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas and adenocarcinomas without a predominant lepidic growth) were separable, as shown in the PCA score plot, Figure 4A. The separation of the two subtypes was mostly along the second principal component, shown on the y-axis. The PCA loading plot in Figure 4B showed that texture was most important for separating the two subtypes, where lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas tended to have more of a ground-glass appearance, i.e. lower value for the texture characteristic. It is also noteworthy that the surrounding tissues and associated findings were important to the PCA model (their loading values were not zero) and added important information to the tumor characteristics, as shown in Figure 4B. Interestingly, adenocarcinomas with only a minimal lepidic component also showed some extent of lepidic growth characteristics. As shown in Figure 4A, some of the adenocarcinomas without a predominant lepidic growth “misclassified” into the subtype of lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas are actually adenocarcinomas with a small proportion of a lepidic component.

Figure 4.

PCA Plot. The score plot (A) shows a separation between the different subtypes: lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas (green squares), adenocarcinomas without a lepidic component (blue circles), and adenocarcinomas with a small proportion of a lepidic component (orange triangles). The loading plot (B) shows how the characteristics are related to each other and which characteristics separate the subtypes. Characteristics related to tumor are represented by blue circles, surrounding tissues by yellow squares, and associated findings by red triangles.

Discussion

In this study we developed 25 CT descriptors among 117 patients with lung adenocarcinoma and found that, of these, pleural attachment was most significantly associated with an increased risk of death overall and among patients with lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas, while lymphadenopathy was significantly associated with an increased risk of death among patients with adenocarcinomas without a predominant lepidic component.

We utilized the lexicon of BI-RADS and the Fleischner Society as the guiding principle to develop our descriptors for lung cancer. However, our goal is not limited to structured reporting; we aim to develop a lexicon that can support automated analysis in the clinical setting by providing guidance and expert evaluation of important imaging characteristics. In many instances documenting the presence of a given characteristic may be insufficient. For example, previous work used spiculation as one possible margin rating. In contrast, we used spiculation as a variable unto itself with five degrees. We intentionally broadened the ordinal scale, which is important for developing quantitative measures that can distinguish prognostic groups with higher resolution and provide the opportunity for automated analytical techniques to be designed to detect features not detectable by the human eyes.

Many investigators 23-27 have reported a correlation between histopathologic and CT findings in adenocarcinomas. Adenocarcinomas showing ground-glass opacity (GGO) on CT usually possess lepidic growth pattern. Our study analyzed the semiquantitative CT characteristics of adenocarcinomas by using PCA modeling and found lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas can be separated from adenocarcinomas without a predominant lepidic growth, and the most important characteristic that differentiated those two subtypes is texture (GGO component). We further analyzed the adenocarcinomas without a predominant lepidic growth and it was interesting that adenocarcinomas with only minimal lepidic component also showed some extent of lepidic growth characteristics. These results suggest semiquantitative CT characteristics can be used to predict histological subtypes of adenocarcinoma based on lepidic component.

Some reports have shown prognostic factors of lung adenocarcinoma from CT findings 24, 28, 29. A smaller extent of GGO, lack of lobulation or air bronchograms, presence of coarse spiculation, or thickening of bronchovascular bundles around the tumors have been correlated with poorer survival, which were similar to our results. However, since some characteristics of our study have only small numbers of individuals for some scales, we can't make a definite conclusion due to the small sample size. We did not observe a relationship between extent of GGO with survival. As this relationship was reported to be found in small (<3 cm) tumors 24, 28, 29, it should be investigated further by quantitative GGO evaluation using computerized methods. This approach would be helpful to find out the prognostic value of GGO or GGO ratioIn particular, we found pleural attachment was one of the most important characteristics correlated with overall survival, especially for lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas. Visceral pleural invasion in lung cancer increases T staging from T1 to T2 even if the tumor is less than 3 cm in size. As we know, simple contact between the tumor and neighboring structures does not necessarily mean invasion, CT findings can be ambiguous concerning thoracic invasion 30. Though the CT findings of pleural attachment differed from pathologically pleural tumor invasion, this simple characteristic appears to have prognostic significance. In addition, we found that the prognostic factors for lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas were different from those for adenocarcinoma without a predominant lepidic growth. This suggests that the different histological subtypes of adenocarcinoma based on lepidic component should be analyzed separately when semiquantitative CT characteristics are assessed for their association with lung cancer outcomes.

There are several limitations in the present study. First, the sample size of our study was 117 patients and only small numbers of cases were rated into the extreme scales of some descriptors, which could have an impact on the survival analysis. Second, the CT parameters were not consistent for all the cases, and some CT scans were not performed with thin slices. However, since this was a retrospective study with five years’ survival status of the patients, we aimed to keep the sample size as large as possible. Third, we classified the tumors according to their growth pattern, we didn't further classify the histological subtype because of the relatively small sample size, and our study showed that CT characteristics and prognostic factors of lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas are different from other subtype of adenocarcinoma. In addition, we did not analyze the impact of surgical technique and other treatments after surgery on survival. Moreover, the information of PET-CT is useful to predict survival, we will include that information in the future studies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the initial results of our study show that semiquantitative CT characteristics were associated with overall survival in a cohort of lung adenocarcinoma patients. Specifically, pleural attachment was associated with an increased risk of death, especially among lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas. Texture was most important for distinguishing lung adenocarcinomas with and without a predominant lepidic component.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Practice Points.

Efforts have been made to develop a standardized lexicon for describing lung tumor features and a standard method for converting these descriptors into quantitative, mineable data with the intent of discovering their associations with patient survival.

A subset of the semiquantitative characteristics described herein has prognostic importance and ability to distinguish between different histological subtypes of lung adenocarcinoma.

The retrievable data elements in the semiquantitative CT characteristics can be used for data mining and developing automated objective features, which would benefit therapy planning and ultimately improve patient care.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute (grants U01 CA143062 and P50 CA119997), Florida Biomedical Research Programs, King Team Science (grant 2KT01), and the Cancer Informatics Core Facility at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, an NCI designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30-CA076292).

The authors thank the collaboration between Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute & Hospital and H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute.

Abbreviations

- CT

computed tomographic

- PCA

principle component analysis

- HR

hazard ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- BI-RADS

breast imaging reporting and data system

- CART

classification and regression tree

- GGO

ground-glass opacity

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auerbach O, Garfinkel L. The changing pattern of lung carcinoma. Cancer. 1991;68:1973–1977. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19911101)68:9<1973::aid-cncr2820680921>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barsky SH, Cameron R, Osann KE, Tomita D, Holmes EC. Rising incidence of bronchioloalveolar lung carcinoma and its unique clinicopathologic features. Cancer. 1994;73:1163–1170. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940215)73:4<1163::aid-cncr2820730407>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sica G, Yoshizawa A, Sima CS, et al. A grading system of lung adenocarcinomas based on histologic pattern is predictive of disease recurrence in stage I tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1155–1162. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181e4ee32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubin DL. Creating and curating a terminology for radiology: ontology modeling and analysis. Journal of digital imaging. 2008;21:355–362. doi: 10.1007/s10278-007-9073-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Opulencia P, Channin DS, Raicu DS, Furst JD. Mapping LIDC, RadLex, and lung nodule image features. Journal of digital imaging. 2011;24:256–270. doi: 10.1007/s10278-010-9285-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Channin DS, Mongkolwat P, Kleper V, Rubin DL. The Annotation and Image Mark-up project. Radiology. 2009;253:590–592. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2533090135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar V, Gu Y, Basu S, et al. Radiomics: the process and the challenges. Magnetic resonance imaging. 2012;30:1234–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aerts HJ, Velazquez ER, Leijenaar RT, et al. Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4006. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yanagawa M, Tanaka Y, Kusumoto M, et al. Automated assessment of malignant degree of small peripheral adenocarcinomas using volumetric CT data: correlation with pathologic prognostic factors. Lung Cancer. 2010;70:286–294. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gimenez F, Xu J, Liu Y, et al. Automatic annotation of radiological observations in liver CT images. AMIA ... Annual Symposium proceedings / AMIA Symposium. AMIA Symposium. 2012;2012:257–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee HJ, Kim YT, Kang CH, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutation in lung adenocarcinomas: relationship with CT characteristics and histologic subtypes. Radiology. 2013;268:254–264. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13112553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Y, Zhou X, Song X, et al. EGFR L858R mutation is associated with lung adenocarcinoma patients with dominant ground-glass opacity. Lung Cancer. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weichert W, Warth A. Early lung cancer with lepidic pattern: adenocarcinoma in situ, minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, and lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2014;20:309–316. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, et al. International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society: international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma: executive summary. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2011;8:381–385. doi: 10.1513/pats.201107-042ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molleran V, Mahoney MC. The BI-RADS breast magnetic resonance imaging lexicon. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2010;18:171–185. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ACR . Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System, Breast Imaging Atlas. 4 ed. American College of Radiology; Reston, VA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Muller NL, Remy J. Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology. 2008;246:697–722. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2462070712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gevaert O, Xu J, Hoang CD, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer: identifying prognostic imaging biomarkers by leveraging public gene expression microarray data--methods and preliminary results. Radiology. 2012;264:387–396. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12111607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsuki Y, Nakamura K, Watanabe H, et al. Usefulness of an artificial neural network for differentiating benign from malignant pulmonary nodules on high-resolution CT: evaluation with receiver operating characteristic analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:657–663. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.3.1780657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mirsadraee S, Oswal D, Alizadeh Y, Caulo A, van Beek E., Jr. The 7th lung cancer TNM classification and staging system: Review of the changes and implications. World J Radiol. 2012;4:128–134. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v4.i4.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee HY, Lee KS. Ground-glass opacity nodules: histopathology, imaging evaluation, and clinical implications. Journal of thoracic imaging. 2011;26:106–118. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e3181fbaa64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aoki T, Tomoda Y, Watanabe H, et al. Peripheral lung adenocarcinoma: correlation of thin-section CT findings with histologic prognostic factors and survival. Radiology. 2001;220:803–809. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2203001701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hashizume T, Yamada K, Okamoto N, et al. Prognostic significance of thin-section CT scan findings in small-sized lung adenocarcinoma. Chest. 2008;133:441–447. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Honda T, Kondo T, Murakami S, et al. Radiographic and pathological analysis of small lung adenocarcinoma using the new IASLC classification. Clin Radiol. 2013;68:e21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lederlin M, Puderbach M, Muley T, et al. Correlation of radio- and histomorphological pattern of pulmonary adenocarcinoma. The European respiratory journal : official journal of the European Society for Clinical Respiratory Physiology. 2013;41:943–951. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00056612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takashima S, Maruyama Y, Hasegawa M, Saito A, Haniuda M, Kadoya M. High-resolution CT features: prognostic significance in peripheral lung adenocarcinoma with bronchioloalveolar carcinoma components. Respiration; international review of thoracic diseases. 2003;70:36–42. doi: 10.1159/000068410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takashima S, Maruyama Y, Hasegawa M, et al. Prognostic significance of high-resolution CT findings in small peripheral adenocarcinoma of the lung: a retrospective study on 64 patients. Lung Cancer. 2002;36:289–295. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(01)00489-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imai K, Minamiya Y, Ishiyama K, et al. Use of CT to evaluate pleural invasion in non-small cell lung cancer: measurement of the ratio of the interface between tumor and neighboring structures to maximum tumor diameter. Radiology. 2013;267:619–626. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.