Summary

The influence of religion on health remains a subject of considerable debate both in developed and developing settings. This study examines the connection between the religious affiliation of the mother and under-five mortality in Mozambique. It uses unique retrospective survey data collected in a predominantly Christian area in Mozambique to compare under-five mortality between children of women affiliated to organised religion and children of non-affiliated women. It finds that mother’s affiliation to any religious organisation, as compared to non-affiliation, has a significant positive effect on child survival net of education and other socio-demographic factors. When the effects of affiliation to specific denominational groups is examined, only affiliation to the Catholic or mainline Protestant churches and affiliation to Apostolic churches are significantly associated with improved child survival. It is argued that the advantages of these groups may be achieved through different mechanisms: the favourable effect on child survival of having mothers affiliated to the Catholic or mainline Protestant churches is likely due to these churches’ stronger connections to the health sector, while the beneficial effect of having an Apostolic mother is probably related to strong social ties and mutual support in Apostolic congregations. The findings thus shed light on multiple pathways through which organised religion can affect child health and survival in sub-Saharan Africa and similar developing settings.

Introduction

This paper uses unique rich survey data to examine the association between religious affiliation and under-five mortality in Mozambique, a country of 23 million people where 142 children out of 1000 new-borns die before reaching the age of five years (WHO, 2011) and about 90% of the population say religion is very important in their lives and most people are affiliated to organised religion (Pew Research Center, 2010). Mozambique is typical of the subcontinent in levels of infant and child mortality. In general, sub-Saharan Africa is the region of the world with the highest under-five mortality rates (WHO, 2011). The United Nations points out that although most causes of child deaths are preventable and treatable, more children die every year in sub-Saharan Africa than anywhere else in the world: of the 8.8 million under-five deaths in the world in 2008, half were in sub-Saharan Africa (United Nations, 2010).

The role of organised religion in Mozambique is also typical of sub-Saharan Africa. Thus, a multi-country survey conducted at the end of the last century showed that in West Africa about 99% of respondents belonged to a religious denomination and 82% attended religious services regularly (Gallup International, 2010). In East and Southern Africa the levels of religious involvement are similarly high: approximately 92% reported to belong to a religious congregation in Malawi (Trinitapoli, 2006), about 70% belonged to a Christian denomination in Zambia (Carmody, 2003) and in South Africa, about 90% of the black population identified themselves with a Christian church (Garner, 2000).

Mozambique also resembles sub-Saharan Africa in Christian denominational diversity. These diverse Christian denominations can be roughly divided into two main groups: the “mainline” denominations and Pentecostal and similar denominations. The first group encompasses Catholic and mainline Protestant churches (e.g., Anglican, Baptist, Methodist and Presbyterian). The second group includes imported Pentecostal churches (e.g., the Assemblies of God), and numerous similar but locally-initiated churches such as Apostolic and Zionist, whose doctrine and practice are focused on faith-healing. The Catholic and mainline Protestant churches are historically more connected to institutions of health care and education; they tend to have more socially diverse and better educated members (Addai, 2000; Garner, 2000; Agadjanian, 2001; Takyi & Addai, 2002; Gyimah et al., 2006) with better household living conditions (Gyimah et al., 2006) compared to members of Pentecostal and especially Zionist churches (Schoffeleers, 1991; Agadjanian, 2001; Pfeiffer, 2002). Although Apostolic churches share many characteristics with Pentecostals and Zionists, they are characterized by a close-knit and cooperative organisation (e.g., Turner, 1980; Bourdillon, 1983; Jules-Rosette, 1997), which sets them apart from much more loosely organised Zionists and other Pentecostal churches. Despite socioeconomic differences among Christian denominations, members of sub-Saharan Christian churches as a whole tend to be better educated and wealthier than individuals belonging to Islam, traditional religions or not affiliated to a formal religion (Kollehlon, 1994; Takyi & Addai, 2002; Gyimah et al., 2006; Antai et al., 2009).

Little research has examined the effect of religion on child health and mortality in the region. The few existing studies about religion and child survival in sub-Saharan Africa suggest that the effect of religion on under-five mortality is typically explained by differences in maternal education and differential use of maternal and child health services among members of different religious groups. Gyimah (2007) investigated differences in child survival by religious affiliation using the 1998 and 2003 Ghana Demographic and Health Surveys. The bivariate analysis showed that children of Muslim women and of those belonging to traditional religion were at a significantly higher risk of dying compared to children of women belonging to mainline, mainstream, Christian denominations, but there were no difference in the risk of death of children between mothers affiliated to mainline Christian denominations and other Christian denominations. However, the association between religious affiliation and child survival observed at the bivariate level disappeared after controlling for socioeconomic factors, especially education.

Another study in Nigeria concluded that the association between belonging to a traditional religion and under-five mortality was explained by religion-related differences in use of maternal and child health services (Antai et al., 2009). In Zimbabwe, Gregson et al. (1999) observed that members of Zionist and Apostolic churches historically showed higher infant mortality than members of mainline (“Mission”) churches, presumably because Zionist and Apostolic churches discouraged the use of both traditional and modern medical services. The authors also noted that the disadvantage of Zionist and Apostolic church members in infant mortality in Zimbabwe diminished since the early 1990s probably owing to enforced immunisation.

Several studies have looked at the association between religious affiliation and child survival in other parts of the world, notably in Latin America. Using the 2000 Demographic Census of Brazil, Wood et al. (2007) examined the association between religious affiliation and child deaths to mothers aged 20 to 34 years in northeast Brazil. They found a significantly lower death rate among children of women affiliated to traditional Protestant (Baptist and Presbyterian) and Pentecostal denominations when compared to children of Catholic women. This difference was attributed mainly to socioeconomic differences between the religious denominations. According to the study, compared to Catholics, traditional Protestants in northeast Brazil are characterised by higher levels of education and household income, are more likely to be married and to live in households with piped water. Bivariate results of another study extended to the whole of Brazil found significantly fewer infant deaths among Protestant mothers when compared to Catholic ones; however, after adjusting for socioeconomic and demographic factors, denominational differences in infant deaths became statistically non-significant (Verona et al., 2010). The findings from both Brazilian studies illustrate the importance of socioeconomic differences across religious denominations in explaining child deaths.

Another study in Mexico (Valle et al., 2009) investigated the effect of religious affiliation of the mother on child mortality among women belonging to indigenous and non-indigenous ethnic groups in Chiapas. For the indigenous group, the study reported significantly lower child mortality among mothers affiliated to the Presbyterian denomination compared to mothers belonging to the Catholic Church, net of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the mother. Among non-indigenous women, religious affiliation of the mother was not significantly associated with child mortality in Chiapas. The authors suggested two possible explanations for their results: Presbyterian women are more likely to use health care services than are Catholic women and there is greater social integration and organisation among Presbyterian congregations compared to Catholic ones. The researchers further noted that indigenous health promoters among Presbyterians provided members with health education and helped members with referral to public and private health services. Overall, the literature on the relationship between religious affiliation and child survival appears to suggest that differences in child survival among religious groups are mostly explained by socioeconomic characteristics of those groups and religion-related differences in use of health care services.

The setting

Mozambique, located in southern Africa, won independence from Portugal in 1975. Soon after independence it went through a prolonged civil war (1976-1992) that destroyed much of the socioeconomic infrastructure of the country (Minter 1994; Abrahamsson & Nilsson 1995). After the signing of a peace agreement and the end of civil war in October 1992, the country embarked in a post-war reconstruction effort, leading to an average economic growth in excess of 7% per year between 1997 and 2010 (UN Mozambique, 2012).

Despite the remarkable economic growth, Mozambique remains one of the poorest countries in the world, with the Gross National Income per capita of $440 in 2010, and life expectancy at birth of 50 years in 2010 (The World Bank, 2012). It is estimated that the country has more than half of its people living below the national poverty line (Republic of Mozambique, 2010). Although the under-five mortality rate in Mozambique showed a dramatic decline in the last two decades, from 232 deaths per 1000 live births in 1990 to 142 deaths per 1000 live births in 2009, it remains one of the highest in the world (WHO, 2011). The country’s poor health indicators exist in an environment of low literacy, particularly among women: the 2003 Mozambique’s Demographic and Health Survey report indicated that 41% of women (aged 15-49 years) and 17% of men (aged 15-64 years) were illiterate among those surveyed (Instituto Nacional de Estatística & Macro International, 2005).

As we noted above, most people in Mozambique identify themselves with a religious congregation: among women aged 15-49 years interviewed in the 2003 Demographic and Health Survey, 30.3% were Catholics, 27.2% Protestant or Evangelical and 18.8% Muslims. Women affiliated with Zionist denominations made up about 8.8%, while women who were not affiliated with any religious denomination constituted 14.5% (Instituto Nacional de Estatística & Macro International, 2005). The national religious distribution masks regional differences, with Muslims primarily concentrated in the North and the coastal strip of Central Mozambique, while Zionists are heavily present in the South.

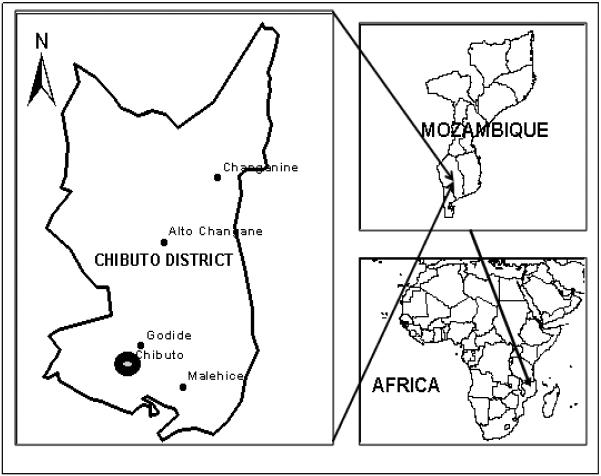

The survey that supplied data for our study was carried out in Chibuto district of the southern province of Gaza (Fig. 1). In 2007 the district had a population estimated at 165,000 inhabitants (Instituto Nacional de Estatística, 2009), and one third of that population lived in the district capital. Rain-dependent agriculture and remittances from migrants working in the Republic of South Africa and the capital of Mozambique, Maputo, are the basis of the district economy. The district’s population is predominantly Christian; the Catholic church, mainline Protestant churches, Apostolic and numerous small Pentecostal-type churches (mainly Zionist churches and the Assemblies of God) are the prevailing religious organisations (Agadjanian, 2005; Agadjanian & Menjivar, 2008).

Fig. 1.

The location of Chibuto district, Gaza province, Mozambique.

Hypotheses

Following previous studies in sub-Saharan Africa (e.g., Gyimah, 2007; Antai et al., 2009), it is expected that under-five mortality of children of mothers affiliated to a religious denomination will be lower than mortality of children of non-affiliated mothers, but this difference will be due to other factors such as higher average level of education and higher living standard of affiliated women.

Recognizing that religious denominations are diverse (Agadjanian, 2005; Mpofu et al., 2011) denominational differences in under-five mortality are expected. Therefore, mortality of children of non-affiliated mothers is compared to mortality of children of mothers affiliated to churches in four denominational groups—Catholic or mainline Protestant (treated as one group), Apostolic, Zionist and other Pentecostal. It is posited that children of women belonging to Catholic or mainline Protestant denominations, when compared to children of women not affiliated to an organised religion, will have particularly low under-five mortality because Catholics and mainline Protestants are typically better educated and higher income and better living conditions than members of most other religious groups (Garner, 2000; Agadjanian, 2001; Takyi & Addai, 2002; Gyimah et al., 2006). In addition, Catholic and mainline Protestant denominations are said to have better access to health services and to encourage the use of these services (Gregson et al., 1999; Agadjanian, 2005), which may contribute to child survival.

It is also expected that children born to Apostolic women will have particularly lower under-five mortality when compared to children of non-affiliated women. Religious teachings among Apostolic encourage cooperative and mutual help life-style (Turner, 1980; Bourdillon, 1983; Jules-Rosette, 1997), which is expected to contribute for child survival beyond mother’s education and household living conditions. While all Christian churches in general stress the importance of organisational solidarity, the emphasis on mutual social support among Apostolic appears to be most pronounced. Although the effect of mutual help on child survival cannot be directly tested with this data, based on the literature (Jarvis & Northcott, 1987; Taylor & Chatters, 1988; Ellison & George, 1994; George et al., 2002; Hummer et al., 2004) it therefore seems reasonable to expect that strong mutual support and help could improve child survival chances among Apostolics.

With respect to children of mothers belonging to Zionist and other Pentecostal denominations it is expected that their survival advantage over children of non-affiliated mothers will be minor if at all present. Zionist and most Pentecostal denominations are among poorer religious organisations in southern Africa and do not have the kind of strong social support mechanisms that characterise Apostolics (Gregson et al., 1999; Agadjanian, 2005).

Data and methods

Data

In the study, data from a survey conducted in Chibuto district in 2008 are used. The survey was a representative cluster survey of 2019 women aged 18-50 years, both affiliated and not affiliated with a religious denomination. In 82 randomly selected communities (clusters) located in both urban and rural areas of the district, the survey collected information on respondents’ complete religious affiliation history since birth until the year of the survey. The survey also collected a variety of information including on respondents’ demographic and socioeconomic characteristics and complete reproductive histories (births and deaths of all of their children). The survey is therefore unique for sub-Saharan Africa in the amount of details about respondents’ religious and reproductive history.

Outcome variable

The outcome variable is the hazard of death before age of 5 years. For every child, the risk period begins at the time of birth. The risk period ends when the child dies, completes 5 years or at the time of the survey for children younger than 5 years who were still alive by the survey date. A person-year file in which each child contributes one observation for every year of life before the end of the risk period is built. For children who were still alive by the survey date, the outcome variable is coded 0 in each year of exposure. Children who died between ages 0 and 5 were coded 0 for each year of life before death and coded 1 in the year of death. Each child stops contributing person-years when the risk period ends. This is a typical data restructuring for discrete-time event-history models (Allison, 1995). The age of children was operationalised as a set of four dummy variables to capture the variation of mortality risk with age: 0 years, 1 year, 2 to 3 years, and 4 to exact 5 years. Children with incomplete birth and death information were excluded from the analysis.

Predictor variables

The main predictor in this study is time-varying mother’s religious affiliation. First, a distinction between women affiliated to an organised religion and non-affiliated women is made. Second, religious affiliation is categorised as follows: 1) Catholic or mainline Protestant; 2) Apostolic; 3) Zionist; 4) Other Pentecostal (Assembly of God included); and 5) Non-affiliated. These categories are derived from respondents’ religious history. For each year of observation, religious affiliation of the respondent is lagged by one year. There were only twelve Muslim women in the survey sample, and they were excluded from the analysis.

As controls, socio-demographic variables typically reported to affect child survival are included (Cleland & Sathar, 1984; Brockerhoff & Derose, 1996; Omariba et al., 2007): mother’s age, number of previously born children, marital status, and the length of preceding birth interval (all time-varying). The length of preceding birth interval is operationalised as follows: less than 2 years and 2 or more years. It is also controlled for the mother’s education at the time of survey as in that setting women typically complete their education before having children. Mother’s education has been found to affect the risk of child survival (e.g., Farah & Preston, 1982; Agha, 2000; Schellenberg et al., 2002). Mother’s education was coded as follows: no education, 1 to 4 years, and 5 or more years. It is also controlled for mother’s place of residence at the time of survey (dichotomised as urban versus rural) as it is also expected to influence child survival (Andoh et al., 2007). To account for the fact that women with sick children might have been selected to joining healing religious organisations, it is controlled for a time-varying variable indicating whether a mother joined a religious denomination due to health problems. This variable is lagged by one year. Because information on household material characteristics is available only for the time of survey, it cannot be controlled for these characteristics. This is acknowledged as a limitation of the analysis.

The statistical model also includes a community-level control and a period control. It is controlled for the average female educational level in the community (computed as the aggregate average of respondents’ education in a survey cluster).The average female educational level in the community has been found to have an effect on child survival beyond the effect of mother’s own education; and it could also be suggestive of the degree of community knowledge about good health behaviour, community environmental hygiene and nutrition (Kravdal, 2004). Although the community average educational level indicator is based on the information at the time of survey, it is used as a marker of human development differentials of the communities covered in the survey that likely existed over a longer period of time. Finally, a measure of historical period of child birth is included as an attempt at capturing the influence of broad socio-economic and political changes in Mozambique in the last 40 years. As it was mentioned, the country went through a period of civil war and post-war reconstruction. It is likely that children born in some years of Mozambican history might have faced an elevated risk of death. Three dummy variables were created to account for the historical period of child birth: born between 1970 and 1992, born between 1993 and 2000, and born between 2001 and 2008. Selected descriptive statistics for the variables used in the analysis are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selected Descriptive Statistics, Survey “Religious Organisations and HIV/AIDS in Mozambique”, 2008

| Catholic or mainline Protestant |

Apostolic | Zionist | Other Pentecostal |

Non- affiliated |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age of mother | 30.4 | 31.5 | 31.3 | 30.9 | 32.7 |

| Mean number of previously born children |

3.3 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 3.7 |

| Mother's education | |||||

| 5 or more years | 46.6 | 27.8 | 22.4 | 38.9 | 11.6 |

| 1 to 4 years | 35.2 | 45.7 | 39.2 | 33.8 | 32.2 |

| None | 18.2 | 26.5 | 38.5 | 27.3 | 56.2 |

| Mother's place of residence | |||||

| Urban | 18.2 | 22.7 | 19.3 | 24.5 | 17.2 |

| Rural | 81.8 | 77.3 | 80.7 | 75.5 | 82.8 |

| Mean level of education in the community |

3.3 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 2.3 |

| Percentage of denominational group in the sample |

21.8 | 11.6 | 41.9 | 10.7 | 11.5 |

Note: The descriptive statistics refer to the year of survey only.

Statistical analysis

To describe the baseline under-five mortality differences between children of non-affiliated women and children of women belonging to each of the denominational categories, five-year probabilities of survival using the Kaplan-Meier (product limit) estimator were estimated. The analysis was done using the LIFETEST procedure in SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., 2008). The Log-rank test was used to assess the equality of survival functions between the children of non-affiliated women and those of women belonging to each one of denominations.

The multivariate analysis employed the discrete-time event history approach. Discrete-time event-history analysis is appropriate because it allows the inclusion in the model of children who are still alive by the time of survey – i.e., censored children (Sear et al., 2002). For analysis the GLIMMIX procedure in SAS 9.2 was used to fit random-effects discrete-time logistic regression models (SAS Institute Inc., 2008). Models with random-effects were employed to take into account that children living in the same village and children born to the same mother may share some unobserved characteristics which may introduce bias to the results (Das Gupta, 1990; Curtis et al., 1993; Sear et al., 2002; Avogo & Agadjanian, 2010).

The statistical model is as follows. Let Yijkt be the event indicator, where Yijkt=1 if child i of woman j and community k experiences death at time t and Yijkt = 0 if the child survives past time t. The model that is fitted may be described by the following equation:

where Pijkt = P[Yijkt = 1/Xijk, Xijkt, Zk]; β1, β2 and β3 are vectors of coefficients; Xijk is a vector of time-fixed woman-level covariates; Xijkt is a vector of time-dependent woman-level covariates, Zk is a vector of time-fixed community level covariate; Ujk and Uk are woman and community-level random effects, respectively.

Results

Table 2 displays comparison of survival probabilities between children of non-affiliated mothers and children of mothers belonging to each one of other religious categories: Catholic or mainline Protestant, Apostolic, Zionist and other Pentecostal. In Table 2, it is observed that children born to mothers belonging to any religious denomination have higher survival probabilities when compared to children of non-affiliated mothers. However, only the survival probabilities of children of Catholic or mainline Protestant and Apostolic mothers are significantly different from those of children born to non-affiliated mothers (Table 2, Log-rank test, p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Kaplan-Meier child survival probabilities, each denominational category versus No affiliation, Survey “Religious Organisations and HIV/AIDS in Mozambique”, 2008

| Probability of survival to age |

No affiliation | Catholic or Mainline Protestant |

Apostolic | Zionist | Pentecostal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 0.969 | 0.977 | 0.977 | 0.973 | 0.971 |

| 2 years | 0.959 | 0.972 | 0.971 | 0.964 | 0.968 |

| 3 years | 0.953 | 0.968 | 0.967 | 0.958 | 0.962 |

| 4 years | 0.949 | 0.964 | 0.963 | 0.955 | 0.961 |

| 5 years | 0.943 | 0.962 | 0.954 | 0.949 | 0.953 |

Notes: Log-rank test: Catholic or mainline Protestant versus No affiliation, p < 0.001; Apostolic versus No affiliation, p = 0.007; Zionist versus No affiliation, p = 0.170; Other Pentecostal versus No affiliation, p = 0.165.

Next the multivariate results are presented. Table 3 shows results of the random-effects discrete-time hazard models predicting the effect of mother’s religious affiliation on under-five mortality. Models 1 and 2 examine the effect of mother’s affiliation to any religious organisation on under-five mortality while Model 3 and 4 examine the effect of mother’s affiliation to specific denominational groups. The results are presented as odds ratios which are obtained by exponentiation of the logistic regression coefficients. The results can also be interpreted as rates because odds are approximately the same as rates when the rates are small or when the events are few compared with the number of periods of exposure to risk.

Table 3.

Odds ratios from random-effects discrete-time hazard models of mother's religious affiliation on under-five mortality, Survey “Organised Religion and HIV/AIDS in Mozambique”, 2008

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother's religious affiliation | ||||

| No affiliation [reference] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Affiliated to an organised religion | 0.80** | 0.85* | ||

| Catholic or mainline Protestant | 0.71** | 0.76* | ||

| Apostolic | 0.75* | 0.78† | ||

| Zionist | 0.87 | 0.92 | ||

| Other Pentecostal | 0.84 | 0.90 | ||

| Child's age | ||||

| 0 years [reference] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 year | 0.39** | 0.40** | 0.39** | 0.40** |

| 2-3 years | 0.25** | 0.25** | 0.25** | 0.25** |

| 4 to exact 5 years | 0.07** | 0.08** | 0.07** | 0.08** |

| Mother's age | 0.97** | 0.97** | ||

| Mother's marital status | ||||

| Not married [reference] | 1 | 1 | ||

| Married | 1.05 | 1.05 | ||

| Number of previously born children | 1.05 | 1.05 | ||

| Birth interval | ||||

| 2 years or more [reference] | 1 | 1 | ||

| Less than 2 | 1.32** | 1.33** | ||

| Mother's education | ||||

| 5 or more years [reference) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 to 4 years | 1.58** | 1.56** | ||

| 0 years | 1.35* | 1.31* | ||

| Mother's place of residence | ||||

| Rural [reference] | 1 | 1 | ||

| Urban | 1.08 | 1.06 | ||

| Mother joined a church for health reasons | 1.01 | 0.96 | ||

| Average level of female education in the community |

0.94 | 0.95 | ||

| Child birth cohort | ||||

| Born 2001 to 2008 [reference] | 1 | 1 | ||

| Born 1993 to 2000 | 1.20† | 1.22† | ||

| Born 1970 to 1992 | 1.04 | 1.06 | ||

| Intercept | 0.10** | 0.11** | 0.10** | 0.11** |

| −2 Res Log Pseudo-likelihood | 170796 | 171952 | 170827 | 171962 |

| Person-years | 26320 | 26296 | 26320 | 26296 |

Levels of significance:

- p<1;

- p≤ .05;

- p≤ .01.

First, it is assessed whether there is a net difference in under-five mortality between children of non-affiliated mothers and children of mothers affiliated to an organised religion regardless of the type of denomination (Model 1 and 2). Model 1 examines the effect of mother’s affiliation to any religious organisation on the rate of child death and displays the baseline hazard. Model 1 indicates that mother’s affiliation to any religious organisation is associated with lower under-five mortality. The rate of death of children of women affiliated to an organised religion is 20% lower than that of children of women with no religious affiliation (the reference category). As expected, the baseline hazard indicates that the rate of death of children is significantly higher in the first year of life and decreases with age. When other control variables are added in Model 2, the magnitude of the effect of mother’s affiliation to organised religion decreases but the effect remains statistically significant. Net of other factors, the rate of death of children of mothers affiliated to an organised religion is 15% lower. This decrease of the effect of the main predictor is due largely to the effect of maternal education. The findings in Model 2 suggest that affiliation to an organised religion has a beneficial effect on child survival, net of other factors.

Models 3-4 test for the effect of mother’s belonging to specific religious denominations on the rate of child death. Model 3 points to a survival advantage of children of women affiliated to any religious denominations, compared to children of women not affiliated to organised religion. However, the coefficients are only statistically significant for the effects of mother’s affiliation to the Catholic church or mainline Protestant denominations and of affiliation to an Apostolic church. Relative to children of non-affiliated women, children born to Catholic or mainline Protestant mothers and to Apostolic mothers have a rate of death that is lower by 29% and 25%, respectively. In Model 4 when adding other covariates, the pattern of denominational differences in child survival remains similar to that observed in Model 3. The rate of death of children born to Catholic or mainline Protestant mothers is lower by 24% than that of children born to mothers belonging to the reference group, net of other factors. Compared to children of non-affiliated women, children of Apostolic women display a rate of death that is lower by 22%, controlling for other factors. For both Catholics/mainline Protestants and Apostolics the effects remain statistically significant (although now only marginally so in the case of Apostolic mothers). The mortality rates of children born to Zionist and to other Pentecostal women are not significantly different from that of children of non-affiliated mothers. In sum, the addition of controls, and most importantly, of mother’s education, barely changed the effect of religious affiliation on under-five mortality. To explore whether the effects of religious affiliation varies by educational level, we also tested for interaction between religious affiliation and education. The parameter estimates for the interaction terms were not statistically significant (not shown).

Finally, because information on household characteristics is available only for the time of the survey, which cannot be extrapolated to a distant past, we ran this same set of models restricting the period of observation to 5 years preceding the survey and included controls for household materials conditions (assuming that these conditions did not change much during that period). The results of these additional tests were essentially the same as those presented here (results are not shown but can be provided upon request).

Discussion and conclusion

In this study, the hypothesis that children of women affiliated to an organised religion irrespective of the religious denomination would have a survival advantage over children of non-affiliated women was first tested. Findings showed that affiliation to any religious organisation significantly decreased the hazard of under-five mortality net of other factors. Given that religious organisations in sub-Saharan Africa are diverse in their composition and characteristics, it was also assessed whether the effect of affiliation to an organised religion on under-five mortality rate could vary by the type of mother’s denomination. The analysis by religious denominations yielded support to the hypotheses that affiliation to Catholic or mainline Protestant churches and affiliation to an Apostolic denomination would offer a child survival advantage relative to non-affiliation. Despite the similarity of the results for the two denominational categories, the mechanisms through which their child survival advantage is achieved are probably very different. Previous studies in sub-Saharan Africa have observed that Catholic or mainline Protestant churches tend to have members with better education (Agadjanian, 2001; Takyi & Addai, 2002; Gyimah et al., 2006). However, in the analysis, the advantage of Catholics and mainline Protestants over non-affiliated women persisted even after controlling for educational differences. Instead, results are interpreted in light of the earlier observations that the Catholic and mainline Protestant churches are better connected to modern medical services both because they have their members who work in the health sector and because they place less faith in miracle healing as other denominations (e.g., Gregson et al., 1999; Agadjanian, 2001; 2005). These connections cannot be documented directly with data and the interpretation therefore remains tentative. In comparison, the favourable effect on child survival of maternal affiliation to an Apostolic church may stem, it is argued, from the high level of social cohesiveness and mutual support among members of Apostolic churches.

The analysis also demonstrated that the survival of children of women belonging to Zionist and to other Pentecostal denominations, i.e., denominations that generally lack the health sector connections of Catholics and mainline Protestant and the social support networks of Apostolics, was not significantly different from that of children whose mothers were not affiliated to a religion. It is important to note, however, that while the survival chances of children of Catholics/mainline Protestant and Apostolics were significantly higher than those of children of non-affiliated women, the differences among religious denominations were not statistically significant after controlling for other factors (results not shown). The findings on child survival advantage related to mother’s affiliation to specific religious groups are similar to those of other studies (e.g., Antai et al., 2009; Valle et al., 2009).

As organised religion continues to wield enormous influence in everyday life in sub-Saharan Africa (Carmody, 2003; Gyimah et al., 2006; Trinitapoli, 2006; Gallup International, 2010) and child mortality in the region remains the highest in the world (WHO, 2011), efforts to improve child survival in the region need to consider the role of religion. The present case study of Mozambique illustrates the need for a better understanding of the role of religious groups’ organisational characteristics and of their position vis-à-vis the health sector. Future research and policy should further explore and engage the implications of these and other dimensions of religious life for child health and wellbeing.

Acknowledgements

The data used in this study were collected with the support of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (grant # R01 HD050175). Insightful comments from anonymous reviewers are also gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Abrahamsson H, Nilsson A. Mozambique: the troubled transition: from socialist construction to free market capitalism. Zed Books; London: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Addai I. Determinants of use of maternal-child health services in rural Ghana. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2000;32(1):15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agadjanian V, Menjívar C. Talking about the “Epidemic of the Millennium”: religion, informal communication, and HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Social Problems. 2008;55(3):301–321. [Google Scholar]

- Agadjanian V. Religion, social milieu, and the contraceptive revolution. Population Studies. 2001;55(135):148. [Google Scholar]

- Agadjanian V. Gender, religious involvement, and HIV/AIDS prevention in Mozambique. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61(1529):1539. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agha S. The determinants of infant mortality in Pakistan. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;51(199):208. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00460-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Survival analysis using SAS: a practical guide. SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Andoh SY, Umezaki M, Nakamura K, Kizuki M, Takano T. Association of household demographic variables with child mortality in Côte D’ivoire. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2007;39(257):265. doi: 10.1017/S0021932006001301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antai D, Ghilagaber G, Wedrén S, Macassa G. Inequalities in under-five mortality in Nigeria: differentials by religious affiliation of the mother. Journal of Religion and Health. 2009;48(3):290–304. doi: 10.1007/s10943-008-9197-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avogo WA, Agadjanian V. Forced migration and child health and mortality in Angola. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70(53):60. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdillon MFC. Christianity and wealth in rural communities in Zimbabwe. Zambezia. 1983;XI(i):37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Brockerhoff M, Derose LF. Child survival in East Africa: the impact of preventive health care. World Development. 1996;24(12):1841–1857. [Google Scholar]

- Carmody B. Religious education and pluralism in Zambia. Religious Education. 2003;98(2):139–154. [Google Scholar]

- Cleland JG, Sathar ZA. The effect of birth spacing on childhood mortality in Pakistan. Population Studies. 1984;38(3):401–418. doi: 10.1080/00324728.1984.10410300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis SL, Diamond I, McDonald JW. Birth interval and family effects on postneonatal mortality in Brazil. Demography. 1993;30(1):33–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das Gupta M. Death clustering, mother’s education and the determinants of child mortality in rural Punjab, India. Population Studies. 1990;44(3):489–505. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, George LK. Religious involvement, social ties, and social support in a southeastern community. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1994;33(1):46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Farah A, Preston SH. Child mortality differentials in Sudan. Population and Development Review. 1982;8(2):365–383. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup International . Religion in the world at the end of the millennium. Gallup International; 2010. Retrieved May 31, 2010. http://www.gallup-international.com/ [Google Scholar]

- Garner RC. Religion as a source of social change in new South Africa. Journal of Religion in Africa. 2000;30(3):310–343. [Google Scholar]

- George LK, Ellison CG, Larson DB. Explaining the relationships between religious involvement and health. Psychological Inquiry. 2002;13(3):190–200. [Google Scholar]

- Gregson S, Zhumu T, Anderson RM, Chandiwana SK. Apostles and Zionists: the influence of religion on demographic change in Zimbabwe. Population Studies. 1999;53(179):193. doi: 10.1080/00324720308084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyimah SO. What has faith got to do with it? Religion and child survival in Ghana. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2007;39(923):937. doi: 10.1017/S0021932007001927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyimah SO, Takyi BK, Addai I. Challenges to the reproductive-health needs of African women: on religion and maternal health utilization in Ghana. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62(2930):2944. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummer RA, Ellison CG, Rogers RG, Moulton BE, Romero RR. Religious involvement and adult mortality in the United States: review and perspective. Sourthern Medical Journal. 2004;97(12):1223–1230. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000146547.03382.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística & Macro International . Moçambique inquérito demográfico e de saúde 2003 [Mozambique demographic and health survey 2003] Instituto Nacional de Estatística and Macro International; Maputo and Calverton: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística . Sinopse dos resultados definitivos do terceiro censo geral de população [Synopsis of definitive results of the third general population census] Instituto Nacional de Estatística; Maputo: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis GK, Northcott HC. Religion and differences in morbidity and mortality. Social Science & Medicine. 1987;25(7):813–824. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jules-Rosette B. At the threshold of the millennium: prophetic movements and independent churches in Central and Southern Africa. Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions. 1997;99(153):167. [Google Scholar]

- Kollehlon KT. Religious affiliation and fertility in Liberia. Journal of Biosocial Sciences. 1994;26(493):507. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000021623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravdal O. Child mortality in India: the community-level effect of education. Population Studies. 2004;58(2):177–192. doi: 10.1080/0032472042000213721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minter W. Apartheid’s contras: An inquiry into the roots of war in Angola and Mozambique. Zed Books; London: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mpofu E, Dune TM, Hallfors DD, Mapfumo J, Mutepfa MM, January J. Apostolic faith church organization contexts for health and wellbeing in women and children. Ethnicity & Health. 2011;16(6):551–66. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2011.583639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omariba DWR, Beaujot R, Rajulton F. Determinants of infant and child mortality in Kenya: an analysis controlling for frailty effects. Population Research and Policy Review. 2007;26(299):321. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center . Tolerance and tension: Islam and Christianity in sub-Saharan Africa. Pew Research Center; Washington, D.C.: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer J. African independent churches in Mozambique: healing the afflictions of inequality. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, New Series. 2002;16(2):176–199. doi: 10.1525/maq.2002.16.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Mozambique Report on the millennium development goals. 2010 Republic of Mozambique. Retrieved on May 24, 2012. http://web.undp.org/africa/documents/mdg/mozambique_september2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT ® 9.2 User’s Guide. SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schellenberg JRM, Nathan R, Abdulla S, Mukasa O, Marchant TJ, Tanner M, et al. Risk factors for child mortality in rural Tanzania. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2002;7(6):506–511. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoffeleers M. Ritual healing and political acquiescence: the case of the Zionist churches in Southern Africa. Journal of the International African Institute. 1991;61(1):1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sear R, Steele F, McGregor IA, Mace R. The effects of kin on child mortality in rural Gambia. Demography. 2002;39(1):43–63. doi: 10.1353/dem.2002.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takyi BK, Addai I. Religious affiliation, marital processes and women's educational attainment in a developing society. Sociology of Religion. 2002;63(2):177–193. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Church members as a source of informal social support. Review of Religious Research. 1988;30(2):193–203. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank World development indicators, Mozambique. 2012 Retrieved May 24, 2012. http://data.worldbank.org/country/mozambique.

- Trinitapoli J. Religious response to AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: an examination of religious congregations in rural Malawi. Review of Religious Research. 2006;47(3):253–270. [Google Scholar]

- Turner HW. African independent churches and economic development. World Development. 1980;8(523):533. [Google Scholar]

- UN Mozambique Mozambique key development indicators. 2012 UN Mozambique. Retrieved May 24, 2012. http://mz.one.un.org/eng/About-Mozambique/Mozambique-Key-Development-Indicators.

- United Nations . The millennium development goals report 2010. United Nations; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Valle EDV, Fernández L, Potter JE. Religious affiliation, ethnicity, and child mortality in Chiapas, México. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2009;48(3):588–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5906.2009.01467.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verona APD, Hummer R, Júnior CSD, De Lima LC. Infant mortality and mothers religious involvement in Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Estudos de População. 2010;27(1):59–74. [Google Scholar]

- WHO [World Health Organization] World health statistics 2011. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2011. Retrieved on May 24, 2012. http://www.doh.gov.za/docs/stats/2011/who.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Wood CH, Williams P, Chijiwa K. Protestantism and child mortality in northeast Brazil, 2000. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2007;46(3):405–416. [Google Scholar]