Abstract

Utilization of sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services can significantly impact health outcomes, such as pregnancy and birth, prenatal and neonatal mortality, maternal morbidity and mortality, and vertical transmission of infectious diseases like HIV/AIDS. It has long been recognized that access to SRH services is essential to positive health outcomes, especially in rural areas of developing countries, where long distances as well as poor transportation conditions, can be potential barriers to health care acquisition. Improving accessibility of health services for target populations is therefore critical for specialized healthcare programs. Thus, understanding and evaluation of current access to health care is crucial. Combining spatial information using geographical information system (GIS) with population survey data, this study details a gravity model-based method to measure and evaluate access to SRH services in rural Mozambique, and analyzes potential geographic access to such services, using family planning as an example. Access is found to be a significant factor in reported behavior, superior to traditional distance-based indicators. Spatial disparities in geographic access among different population groups also appear to exist, likely affecting overall program success.

Keywords: Geographic access, Health care, GIS, Mozambique

Introduction

Utilization of health services significantly impacts health outcomes. It has long been recognized that access to health services is essential to how people utilize such services (Gulliford & Morgan, 2003; Higgs, 2009; Joseph & Phillips, 1984; Meade & Emch, 2010). This is especially true for rural areas of resource-limited developing countries characterized by poor overall health, such as those in rural sub-Saharan Africa (Stock, 1983; Tanser, Gijsbertsen, & Herbst, 2006). Improving accessibility of health services for greater quality of life, enhanced overall health and well-being, reduced health inequities and better service to target populations is a central concern in health resource allocation and program planning. Therefore, understanding and evaluating access to health care and its spatial variation are vital for healthcare planners and policy makers.

Though it is widely acknowledged that access is crucial for healthcare utilization, access is defined differently and has different implications in different settings (Aday & Andersen, 1975; Cromley & McLafferty, 2011; Gulliford et al., 2002; Joseph & Phillips, 1984; Wang, 2012). Generally, access can be measured in two distinct, yet interacting dimensions: geographic/spatial and non-spatial (Donabedian, 1973). Geographic access highlights the spatial separation (distance, rivers, forests, mountains, etc.) between health facilities and the population in need of service. Non-spatial access, in contrast, refers to demographic, social-economical and organizational factors (sex, age, education, income, religion, etc.) that facilitate or hinder the acquisition of healthcare. From the perspective of utilization, two types of accessibility can be distinguished: potential and revealed (Joseph & Bantock, 1982; Joseph & Phillips, 1984). The former describes the opportunity to use health services, whereas the latter refers to actual achievement of potential access, that is, utilization.

Of interest in this study is potential geographic access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services, and in particular to family planning in rural Africa. It has been found that geographic access to SRH services is an important factor influencing health outcomes such as pregnancy and birth, prenatal and neonatal mortality, maternal morbidity and mortality, and vertical transmission of infectious diseases like HIV/AIDS (Acharya & Cleland, 2000; Rahman, Mosley, Ahmed, & Akhter, 2008; Tanser et al., 2006). As is the case in other types of health care, geographic access to SRH services can be defined in many ways, including travel distance/time/costs (Nemet & Bailey, 2000), gravity-based metrics (Joseph & Bantock, 1982) and more recently, the two-step floating catchment area (2SFCA) (Luo & Wang, 2003; Wang & Luo, 2005). In the context of rural Africa, current research of geographic access to healthcare primarily relies on distance-based measures (Buor, 2003; Noor, Zurovac, Hay, Ochola, & Snow, 2003; Stock, 1983; Tanser et al., 2006). The value of alternative measures is worth further exploration.

Given their capability of managing and processing spatial data, geographic information systems (GIS) are well suited for evaluating geographic access to health services (Cromley & McLafferty, 2011; Higgs, 2004; Meade & Emch, 2010; Rushton, 2003; Wang, 2012; Yao, Murray, Agadjanian, & Hayford, 2012). Desktop mapping makes it easy and straightforward to visualize health data in different spatial representations and under various spatial scales. Also, some spatial operations, such as data aggregation and calculation of travel distance/time/costs, can be easily implemented using readily available functions in GIS. Further, spatial analysis using GIS can provide insights into disparities in geographic access among a population across space, helping identify insufficient health service access and possible influencing factors that otherwise cannot be detected.

The aim of this study is to develop a geographic access index in a GIS environment capable of reflecting important spatial influences and variability to SRH services in rural Africa, using access to family planning in rural areas of Mozambique as an example. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The next section provides an overview of current research on access, especially geographic/spatial access, to health services. The study area and data utilized are then described. We then provide a detailed description of the proposed method. An application of the new method to examine geographic access to SRH services is then presented, focusing on variation over space and the impact on actual health care usage by women in rural Mozambique. We conclude with a discussion of the results and implications.

Background

Healthcare access is a multidimensional concept, and in recent years there has been increasing interest and research on access in a number of fields, including hygiene, economics, geography, sociology, and public policy, among others (Cromley & McLafferty, 2011; Gulliford & Morgan, 2003; Joseph & Phillips, 1984). As a result, numerous definitions of access have been proposed in the literature oriented to different academic specialties. One of the earliest definitions explains access in terms of entry to the health care system (Donabedian, 1973). Similarly, Aday and Andersen (1975) suggested that access is more relevant to consumers of health services compared to suppliers, describing whether people can enter the healthcare system, either potentially or actually. Penchansky and Thomas (1981) identified five dimensions of access: availability, accessibility, accommodation, affordability and acceptability, highlighting the match between health providers and their clients. The first two are defined in spatial terms, where availability implies adequacy of healthcare provision and accessibility refers to geographic impedance (travel distance/time) between healthcare supply and demand. It is worth noting that geographic access has long been a major concern in rural health service systems (Arcury et al., 2005; McGrail & Humphreys, 2009; Stock, 1983). The focus of our paper is on spatial aspects of access, so the remainder of this section is limited to specific aspects of geographic access, including provider-to-population ratios, distance-based measures, and gravity-based models.

Provider-to-population ratio, or physician-to-population ratio, has long been used to measure geographical access to health services (Guagliardo, 2004; Wang, 2012). Usually, the ratio can be calculated using population/physician data aggregated by administrative units such as county or city. This traditional measure has raised a lot of criticism mainly because it fails to account for the variation in spatial access within administrative boundaries and the interaction between provider and population (Guagliardo, 2004). Also, it might not be appropriate to define the catchment area of health facilities using prespecified spatial units because health service areas usually overlap rather than are separated by distinct boundaries. Further, provider-to-population ratios derived on various spatial scales can lead to quite different conclusions on spatial disparities in geographic access, which is well known in geography as the modifiable areal unit problem (MAUP) (Openshaw, 1984).

Distance-based measures can avoid some of the problems associated with provider-to-population ratios (Cromley & McLafferty, 2011). In fact, they are increasingly employed in geographic access evaluation largely thanks to the advance of GIS and increased availability of digitized spatial data (Higgs, 2004; Rushton, 2003). In principle, such measures can be defined using Euclidean distance, distance along road network, travel time or costs. Though straightforward and easy to calculate, Euclidean distance has been considered less than ideal because it ignores physical barriers (e.g. rivers and mountains) and other factors (e.g. road types and transportation modes) that might affect the actual travel distance (Martin, Jordan, & Roderick, 2008). Some studies, however, found it adequate for explaining spatial impedance in healthcare seeking in rural areas (Stock, 1983) and also being a valid proxy for actual travel distance (Cudnik, Yao, Zive, Newgard, & Murray, 2012). To account for actual transportation conditions, distance along road networks and travel time/costs have been used as surrogates for geographic access (Lovett, Haynes, Sunnenberg, & Gale, 2002). Some studies incorporated more complex factors such as transportation modes (e.g. public or private) and timetables (Arcury et al., 2005; Martin et al., 2008). Fortney, Rost, and Warren (2000) compared various distance-based access measures and examined the sensitivity of results obtained from different measures.

Though it has been recognized that distance represented by various measures has a significant impact on the utilization of health service as discussed above, most research fails to consider the characteristics of either health providers (e.g. size of health facility and service quality) or populations, which these providers serve (e.g. access to transportation). In fact, people usually trade off distance and desired health services when making decisions on health care utilization (Rosero-Bixby, 2004). Gravity-based models are methods that can account for such trade-offs. The gravity model originated from Newtonian physics and was extended in economic geography to delineate trade areas (Huff, 1963, 1964). Joseph and Bantock (1982) modified it to measure geographic access to health services, incorporating interaction between supply and demand and considering a nearby healthcare facility more accessible than a distant one. Since then, many extensions of the gravity model have been proposed, such as the two-step floating catchment area (2SFCA) (Luo & Wang, 2003). One limitation of 2SFCA lies in its reliance on the availability measure that is based on provider-to-population ratio. Also, the constant catchment radius used in the model might not reflect the variation among health service provision or community characteristics. Many improvements have been made with regard to the 2SFCA method, such as adoption of varying catchment areas (Luo & Whippo, 2012) and application of different distance decay functions (Luo & Qi, 2009; McGrail & Humphreys, 2009).

In summary, the review above shows that while all the geographic access measures used to date are important in evaluating spatial inequities in access and understanding spatial patterns of health service utilization, they all are subject to limitations in one or more respects. Moreover, in Africa, most recent work on geographic access to health care has employed distance-based measures (Buor, 2003; Noor et al., 2003; Stock, 1983; Tanser et al., 2006). More sophisticated measures for access to health services, such as gravity-based models have not been considered, with the exception of a study by Wilson and Blower (2007) that proposed a gravity model to assess HIV/AIDS treatment accessibility in South Africa. The intent of this study is to develop a geographic access index based on the gravity model for SRH services, which is also adjusted to a specific research context.

Data and study area

The data used in this study are from a survey conducted in 2009 in rural areas of four districts (Chibuto, Chokwè, Guíjà and Mandlakaze) of Gaza province in southern Mozambique, an impoverished nation in southeast Africa. The study region covers an area of approximately 5900 square miles with a population of about 625,000, served by fifty-three state-run primary health clinics. The local economy is largely dependent on subsistence agriculture. Due to poor agricultural yields and the proximity to the border of Mozambique with South Africa, Gaza province has a high volume of male labor outmigration to that neighboring country, which can be traced back to colonial times (De Vletter, 2007). Fertility in the area is high, and so are maternal mortality and morbidity. SRH services, such as provision of family planning, are relatively limited. Also, Gaza province has the highest HIV prevalence in Mozambique, 25% of adult population (Ministry of Health, 2010), and improvement in access to SRH services is an urgent task for the local health care system.

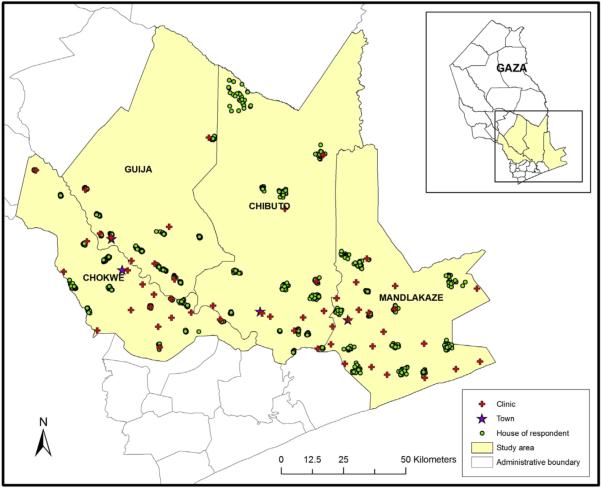

The 2009 survey sample included 1867 women from 56 villages (14 villages per district). The survey was a second wave of a longitudinal survey for which the sample was originally drawn in 2006. In that year, within each of the 56 villages, approximately 15 women married to migrants and 15 women married to non-migrants aged 18–40 were selected from village household rosters through probability sampling. In both survey waves, the geographic location of each respondent was recorded as a spatial point represented by latitude and longitude, along with information on age, educational level, household characteristics, husband’s migration status, and reproductive health and behavior-related information, etc. In addition, some community-based information was also collected, including cost of travel to the nearest town by public transportation. The share of households with a migrant in a community was derived on the basis of household rosters used in the 2006 sampling. Finally, additional community characteristics, such as percent of women with five or more years of schooling, percent affiliated to a formal religion, and percent of households with a radio, were created as aggregate averages of the survey sample. Fig. 1 depicts the spatial distribution of respondents’ residences, health service units, and towns (district centers) of the four districts. As can be seen from Fig. 1, most women in the sample, as the majority of the population, lived in the southern part of the study area whereas the northern part is relatively sparsely populated. A similar pattern can be observed for health facilities, most of which are located in the south.

Fig. 1.

Study area and data.

The SRH outcome used in this study is current use of a modern family planning method. Family planning programs in high-fertility African countries have been credited for improving SRH and reducing maternal and childhood deaths (Benefo & Pillai, 2005; Caldwell & Caldwell, 2002; Cleland et al., 2006). In Mozambique, family planning programs have existed since the early 1980s, with the primary goal to enhance the health of women and children through birth spacing (Ministry of Health, 2010). Currently, family planning services in rural areas are offered almost entirely through state-run maternal and child health clinics, where both consultations and methods are provided completely free of charge. Clients are typically offered a choice among injectable contraceptives (Depo-Provera), oral contraceptives, the intra-uterine device (IUD), and male condoms (female condoms are rarely available). However, modern contraceptive prevalence among married women in rural areas of Mozambique remains low – about 11% on average, according to the 2011 Mozambique Demographic and Health Survey (Instituto Nacional de Estatística and Macro International, 2013). The low contraceptive prevalence is partially attributed to the physical barriers in accessing these types of services. In our study, the patient flow for family planning services in each clinic is used to estimate a hedonic model, and the percent of women that use family planning in each community (derived from the survey sample) is employed as a proxy for the utilization of family planning services to evaluate the impact of geographic access.

Methods

In this study, spatial information and attribute variables are combined in the definition of geographic access. Specifically, characteristics of health facilities are integrated in a hedonic model to evaluate the overall service quality of health providers, which is then incorporated into a gravity-based model to define access. Spatial variation of geographic access is further explored by Kernel density estimation, a GIS-based spatial analysis technique. Regression analysis is utilized to investigate the impact of potential geographic access on the actual pattern of family planning service use. GIS is employed to manage spatial information as well as to derive geographic measures in order to facilitate above procedures.

Essential here is the measure of geographic access. The geographic access index is derived in two steps. First, a health service quality (HSQ) index is derived for each clinic in the study area. Specifically, the HSQ index is the weighted sum of attributes for health facilities:

| (1) |

where

i: index of variable, i = 1,2,3,4,5

j: index of clinic, j = 1,2,.,53

vi: ith variable

wi: weight for ith variable

aj: HSQ index of jth clinic

Hedonic models are widely applied in value estimation (e.g. market or property price) by combining the contributory values of composite variables (Freeman, 2003). Similar to “access”, HSQ is also a complex concept, which involves many aspects of health service (Kenagy, Berwick, & Shore, 1999; Taylor & Cronin, 1994). For example, Dagger, Sweeney, and Johnson (2007) suggested that HSQ primarily concerns interpersonal, technical, environment and administrative qualities. For the application here, the choice of relevant factors is also driven by context-specific considerations as well as data availability. Specifically, the variables describing clinics include number of nurses (variable 1), number of rooms (variable 2), whether or not the clinic has piped water (variable 3), whether or not the clinic electricity (variable 4), and whether or not the clinic has received aid from any non-governmental organization (NGO) (variable 5). Because the last three variables are binary (either 0 or 1), the data for the first two variables are standardized so that all the values range from 0 to 1. By definition, higher values of the HSQ index reflect better health services.

Hedonic models are usually estimated using regression methods. In this case, the weight of each variable is determined with a Poisson regression analysis of the actual health care utilization data in the sample. In our case, the explanatory factors are the five attributes of the clinic defined above. The dependent variable is the patient flow (average number of monthly patients) of each clinic for family planning services.

In the second step, the HSQ index is incorporated into a gravity model to calculate the potential geographic access. This is done to explicitly account for spatial proximity and the well-known distance decay effects observed for service utilization. In this process, the sample data are aggregated to the community level because the health care seeking behavior in the study area largely relies on public transportation or walking, and can be considered invariant for the people in the same village. Suppose dkj is the distance or travel time/costs from community k to the clinic j, generally, the potential access of community k to health services, Ak, can be defined by the following gravity model (Cromley & McLafferty, 2011; Hansen, 1959):

| (2) |

which can be considered the sum of potential access to each clinic j, aj/f(dkj). In healthcare access research, the numerator also can represent service availability defined by the physician-to-population ratio (Luo & Wang, 2003; Wang & Luo, 2005) instead of service quality, aj, used in this study. The denominator f(dkj) is usually some function representing the tendency for reduced activity rates with increasing distance, known as “distance decay” in geography (Haggett, Cliff, & Frey, 1977). In the traditional gravity model, f(dkj) has the following form:

| (3) |

where β is the impedance or travel/distance friction coefficient (a value of 2 is used in the Newtonian gravity model). In practice, the value varies depending on the context under consideration. Higher values of Ak represent better geographic access, implying a greater likelihood of using health services.

This study made two adjustments to the potential geographic access measure given in (2). First, considering the actual public transportation situation in the study area, the distance decay effect is mitigated by the ease of getting to the nearest town because each community is directly connected by public transportation to nearby towns, making travel possible if necessary. In other words, living closer to a town implies better transportation opportunities. Specifically, the distance friction is multiplied by a weight defined as the Euclidean distance from a community to the nearest town divided by the sum of all such distances. Thus, all the weights add up to 1. In the absence of data on actual travel time, Euclidean distance is considered a reasonable proxy for proximity in rural Africa (Stock, 1983; Tanser et al., 2006). In addition, β = 1 is used as the impedance coefficient as it is considered sufficient for the spatial context under study. The distance decay function therefore is:

| (4) |

where wk weight for access to town for kth community.

Another modification concerns the maximum distance that people are willing to travel to acquire healthcare services, which has long been known in geography as “range” (Christaller, 1933). As the study area is rural, it is common for people to visit only the health services within a certain spatial extent. In other words, people rarely visit a clinic beyond a distance threshold. Here this threshold is assumed to be approximately 10 km. The developed potential geographic access index is:

| (5) |

where d0 = distance threshold for visiting a health care unit.

Once the index Ak is derived for each community, GIS-based techniques can help to explored spatial patterns of geographic access over the study area. This enables communities having poorer geographic access to local SRH services to be identified, providing useful information for future improvement programs targeting these areas. In this study, assessment is achieved through Kernel density estimation (Diggle, 1985). Of course, desktop mapping can offer a straightforward view of the differences among communities based on the values of access indices. The advantage of the Kernel density method is that it can fit a continuous surface using a finite set of samples, providing insights into continuous variation in geographic access across the study area. Kernel density estimation is a non-parametric smoothing technique that calculates probability densities at any location in continuous space using a kernel function. In health research, it is usually employed to estimate the probability that an event or a disease will occur (Waller & Gotway, 2004). In this case, a continuous surface is estimated from discrete points of clinics with value Ak. The attribute value associated with a point on the surface represents the probability that a location has good access to health services.

However, actual inequities in health service utilization can be more complicated than simple physical access. Regression analysis helps to understand the impact of geographic access relative to that of other factors on the utilization of SRH services. Service utilization is clearly important, and health outcomes are likely dependent on usage. Thus, the share of respondents that utilize family planning services in each community is used as the dependent variable in a general linear regression model, representing actual utilization of SRH services. The regression model accounts for a variety of factors that are known to affect family planning use. For example, it is well recognized that education and economic status have great influence on healthcare utilization, and use of family planning is no exception (Martin, 1995; Obare, van der Kwaak, & Birungi, 2012; Riyami, Afifi, & Mabry, 2004). Likewise, migration has been shown to affect health care utilization between migrant and non-migrant populations (Newbold & Willinsky, 2009; Ostrach, 2013; Pavlish, Noor, & Brandt, 2010). Religion affiliation can also influence fertility regulation (Adongo, Phillips, & Binka, 1998; Agadjanian, 2001; Agadjanian, Yabiku, & Fawcett, 2009). Given the potential influences of non-spatial factors, other community-level explanatory variables, in addition to geographic access, are also taken into account in the regression analysis, including percent of respondents with at least five years of schooling, percent of those with migrant husbands, percent of those with religious affiliation, the average number of households owning a radio set (a proxy for community economic status), and typical cost of public transportation to the nearest town.

Results

The Poisson regression analysis results on patient utilization of family planning for each clinic using relevant variables are summarized in Table 1. It turns out that only one clinic attribute, “the number of nurses”, has a significant influence on the patient flow of the clinics for family planning services. Thus, this attribute is considered most important in defining the service quality of the clinic. Given the fact that the regression is carried out on sample data and considering the potential impact that other attributes could have on family planning seeking behavior, weights are also assigned to the other four attributes, but these weights are much smaller than that of “the number of nurses”. Based on Equation (1), the first variable is given the largest weight, and the other variables are equally weighted, with the sum of all the weights being one, as shown in Equation (6).

Table 1.

Results of Poisson regression of the clinic patient flow, parameter estimates and standard errors. Sample size: 53.

| Variables | Estimate | Std. error |

|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 2.030** | 0.074 |

| Number of nurses in a clinic | 0.439** | 0.030 |

| Number of rooms in a clinic | 0.129 | 0.025 |

| Clinic has piped water (1) | 0.629 | 0.099 |

| Clinic has electricity (1) | 0.582 | 0.065 |

| Clinic has received assistance from an NGO (1) | 0.075 | 0.063 |

Significance codes:

p < 0.01:

| (6) |

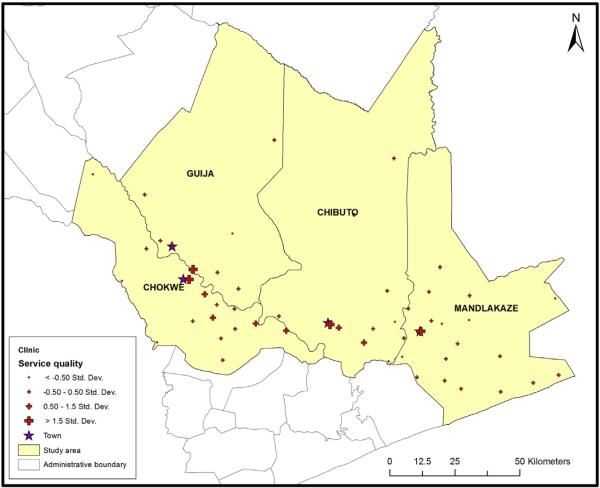

The spatial variation in HSQ is illustrated in Fig. 2 based on symbol size. The three clinics in the towns of Chibuto, Chokwè and Mandlakaze (the headquarters of the respective districts) have higher service quality indices than the other clinics, while the much smaller town of Guíjà (the headquarters of Guíjà district) has lower service quality. The best clinic in Guíjà is very close to the town of Chokwè. It is not surprising that the health facilities close to these towns have better resources. In contrast, most clinics located further away from these towns have much lower service quality.

Fig. 2.

Health service quality of clinics.

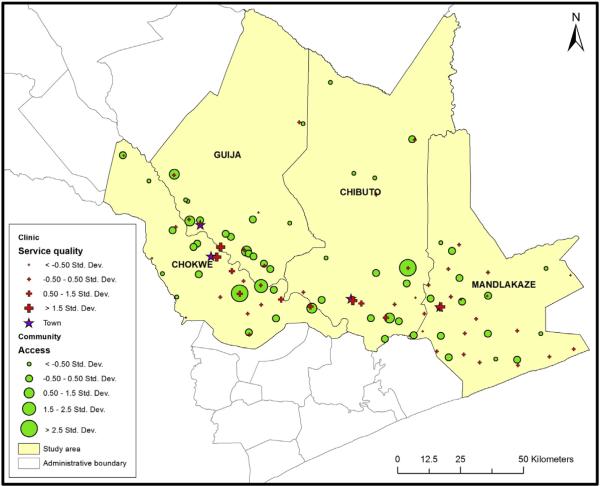

The potential geographic access index is derived using Equation (5). The spatial pattern of the values of the index can be observed in Fig. 3. Each community has a circle whose size reflects its relative level of potential geographic access to local SRH services. By visual inspection, it is not difficult to conclude that the two communities having best potential geographic access are not closest to the best clinic or the town centers. This is no doubt a function of both the facility characteristics and the distance factor. The two communities with the highest access do have a clinic nearby. However, these two clinics are different in terms of service quality, possibly attributed to available services, which reflects a trade-off between service quality and distance associated with actual access. Again, most communities that have worse access are far away from towns, especially the four villages in the north and those near the southern border of the study area.

Fig. 3.

Potential geographic access of communities.

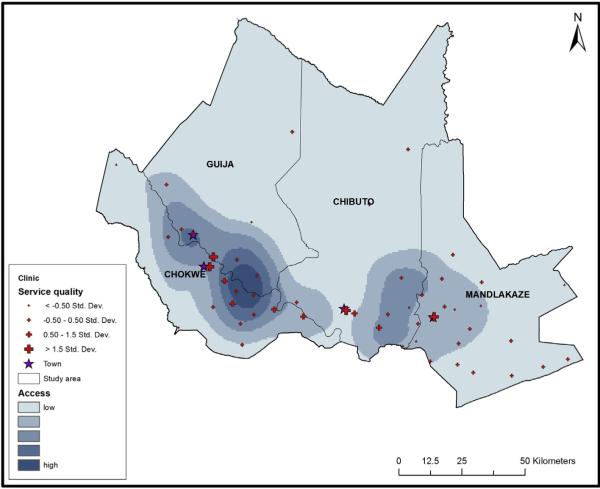

When a surface based on Kernel density estimation is generated using derived index values, the continuous spatial variation of potential geographic access over space can be observed (see Fig. 4). The access potential is shown in five classes using different rendering, with the darker color representing better access. It is clear that the extent to which potential access differs is not consistent with administrative boundaries, as the provider-to-population method would assume. On the whole, women living in the south of the study area have better access to SRH services than those living in the north, which can be attributed to fewer clinics and larger distances from the towns in the northern areas. Also, the population around the towns has more opportunities to be served, especially in the southwestern part of the study area. The exception is an area near the town of Chibuto, largely due to the fact that it does not contain any survey data.

Fig. 4.

Spatial variation of potential geographic access.

To further investigate the impact of geographic access, regression analysis was carried out. The results are shown in Table 2. A pronounced association between potential geographic access and actual service use is observed. That is, the utilization ratio of family planning services declines as geographic access decreases. In addition, some non-spatial factors also affect utilization of family planning. For example, Table 2 indicates that utilization increases with higher educational level and lower cost of public transportation to the nearest town. The reasonably strong linear fit (51.8%) implies that additional factors help explain actual family planning service use. The most important implication of the results presented in Table 2 is that, in terms of public policy, to further improve utilization of SRH services such as family planning, more effort should be devoted to improving education, public transportation as well as geographic access. According to the measure definition, (5), developing the public transportation system and enhancing relevant health services can be efficient ways to increase potential geographic access.

Table 2.

A general linear model of the utilization ratio of family planning services in each community, parameter estimates and standard errors. Sample size: 56.

| Variables | Estimate | Std. error |

|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.235 | 0.152 |

| Percent in community with 5 or more years of education | 0.174* | 0.075 |

| Percent in community with religious affiliation | 0.124 | 0.108 |

| Percent in community with migrant husband | −0.175 | 0.106 |

| Average number of radios possessed in community | 0.161+ | 0.091 |

| Typical cost of public transportation to nearest town | −0.148** | 0.051 |

| Potential geographic access | 0.090** | 0.028 |

Significance codes:

p < 0.01:

p < 0.05:

p < 0.1:

Discussion

As is well known, access is a critical factor impacting health service utilization. Quantitative measures can help to evaluate access and identify deficiencies in service coverage as well as disadvantaged population in subsequent analysis. However, most research has been limited to urban areas (e.g. Lovett et al., 2002; Luo & Wang, 2003; Schuurman, Berube, & Crooks, 2010) or rural areas in developed countries (e.g. Arcury et al., 2005; Joseph & Bantock, 1982; McGrail & Humphreys, 2009; Nemet & Bailey, 2000). The existing measures are not effective for rural areas in developing nations due to different health policies, health delivery systems, or health seeking behavior. Thus, addressing access for people living in such areas continues to pose serious challenges. Using GIS-based techniques, this study developed a gravity-based model to measure geographic access to SRH services in rural Mozambique and investigated spatial inequities in access among population groups.

In a previous study focused on the same setting, Yao et al. (2012) found that geographic access has no significant impact on the utilization of SRH services like family planning when using Euclidean distance. The access index developed in this study, in contrast, showed a much higher explanatory power (and more significant effects) than in previous work. That is, a strong association between potential geographic access and actual service use was identified. Therefore, the proposed access measure is superior to more simplistic measures of access such as Euclidean distance.

The proposed measure can be viewed as a generalization of the 2SFCA method (Luo & Wang, 2003) in the sense that initially the service quality of health facilities is defined, which is then mitigated by distance decay effects. In this case, the service quality of local health clinics is defined using a series of attributes which are combined by different weights calculated from actual survey data; whereas in 2SFCA, as well as many similar models (e.g. Luo & Qi, 2009) it is described by provider-to-population ratios. In addition, a threshold of travel distance of 10 km is applied according to the underlying research context whereas 2SFCA uses a 30 min travel time to define the catchment area for both supply and demand. Further, the developed index can also be thought of as a special case of the enhanced 2SFCA (E2SFCA) (Luo & Qi, 2009) because both weights are considered in the distance decay functions. E2SFCA assigned different weights for each travel time zone, which in the proposed approach is calculated using “distance to town” to account for access to public transportation, highlighting the underlying spatial context.

One limitation of the geographic access measure derived from aggregated data is that it can mask variations among individuals in the same community. Health care utilization can be affected by many personal characteristics, such as age, social class, economic status, transportation opportunities, or activity space. Thus, geographic access can have different implications to different individuals. For example, Nemet and Bailey (2000) found that distance is a significant physical barrier for rural elderly. Perry and Gesler (2000) and Haynes (2003) suggested activity space is a potential aspect of geographic access as people having health facilities within their activity space are more likely to obtain health services. More detailed data on the study setting than what are currently available are needed to account for these characteristics.

Conclusion

Improving access to health services is a great concern of government and policy makers striving to enhance overall public health. Spatial patterns of access to health services are complex products of distance effects, environmental influences, socioeconomic factors, individual and community characteristics, etc. The index proposed in our study is effective in revealing potential geographic influences on access to SRH services in rural Mozambique, which cannot be detected by traditional distance indicators. The results of this study therefore can help future health program development and service deployment in sub-Saharan Africa, especially in poor rural settings. As increasing efforts are devoted to improving SRH service utilization in such settings, geographic dimensions of access to these services should be taken into full consideration.

Acknowledgments

We thank the support of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (grants #R21HD048257; R01HD058365; R01HD058365-03S1).

References

- Acharya LB, Cleland J. Maternal and child health services in rural Nepal: does access or quality matter more? Health Policy and Planning. 2000;15(2):223–229. doi: 10.1093/heapol/15.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aday LA, Andersen R. Development of indices of access to medical care. Health Administration Press; Ann Arbour: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Adongo PB, Phillips JF, Binka FN. The influence of traditional religion on fertility regulation among the Kassena-Nankana of northern Ghana. Studies in Family Planning. 1998;29(1):23–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agadjanian V. Religion, social milieu, and the contraceptive revolution. Population Studies. 2001;55(2):135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Agadjanian V, Yabiku ST, Fawcett L. History, community milieu, and ChristianeMuslim differentials in contraceptive use in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2009;48(3):462–479. [Google Scholar]

- Arcury TA, Gesler WM, Preisser JS, Sherman J, Spencer J, Perin J. The effects of geography and spatial behavior on health care utilization among the residents of a rural region. Health Services Research. 2005;40:135–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00346.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benefo KD, Pillai VK. The reproductive effects of family planning programs in rural Ghana: analysis by gender. Journal of Asian and African Studies. 2005;40(6):463–477. [Google Scholar]

- Buor D. Analysing the primacy of distance in the utilization of health services in the Ahafo-Ano South district, Ghana. International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2003;18(4):293–311. doi: 10.1002/hpm.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JC, Caldwell P. Africa: the new family planning frontier. Studies in Family Planning. 2002;33(1):76–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2002.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christaller W. Die zentralen Orte in Suddeutschland. 1933 English translation, C.W. Baskin, 1966, Central places in southern Germany. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Cleland J, Bernstein S, Ezeh A, Faundes A, Glasier A, Innis J. Family planning: the unfinished agenda. The Lancet. 2006;368(9549):1810–1827. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromley EK, McLafferty S. GIS and public health. 2nd Guilford Press; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cudnik MT, Yao J, Zive D, Newgard C, Murray AT. Surrogate markers of transport distance for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2012;16(2):266–272. doi: 10.3109/10903127.2011.615009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagger TS, Sweeney JC, Johnson LW. A hierarchical model of health service quality: scale development and investigation of an integrated model. Journal of Service Research. 2007;10(2):123–142. [Google Scholar]

- De Vletter F. Migration and development in Mozambique: poverty, inequality and survival. Development Southern Africa. 2007;24:137–153. [Google Scholar]

- Diggle PJ. A kernel method for smoothing point process data. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series C. 1985;34(2):138–147. [Google Scholar]

- Donabedian A. Aspects of medical care administration. Harvard University Press; Cambridge: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Fortney J, Rost K, Warren J. Comparing alternative methods of measuring geographic access to health services. Health Services and Outcomes Research Methodology. 2000;1:173–184. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman AM. The measurement of environmental and resource values: Theory and methods. Resources for the Future; Washington: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Guagliardo M. Spatial accessibility of primary care: concepts, methods and challenges. International Journal of Health Geographics. 2004;3(3):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulliford M, Figueroa-Munoz J, Morgan M, Hughes D, Gibson B, Beech R, et al. What does ‘access to health care’ mean? Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 2002;7(3):186–188. doi: 10.1258/135581902760082517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulliford M, Morgan M. Access to health care. Routledge; London: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Haggett P, Cliff AD, Frey A. Locational analysis in human geography 1: Locational models. Edward Arnold; London: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen WG. How accessibility shapes land use. Journal of the American Institute of Planners. 1959;25:73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes R. Geographical access to health care. In: Gulliford M, Morgan M, editors. Access to health care. Routledge; London: 2003. pp. 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- Higgs G. A literature review of the use of GIS-based measures of access to health care services. Health Services and Outcomes Research Methodology. 2004;5(2):119–139. [Google Scholar]

- Higgs G. The role of GIS for health utilization studies: literature review. Health Services and Outcomes Research Methodology. 2009;9(2):84–99. [Google Scholar]

- Huff DL. A probabilistic analysis of shopping center trade areas. Land Economics. 1963;39:81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Huff DL. Defining and estimating a trading area. Journal of Marketing. 1964;28:34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística and Macro International . Mozambique demographic and health survey 2011. Instituto Nacional de Estatística. Mozambique and MEASURE DHS/ICF International; Calverton, MD, U.S.A. Maputo: 2013. in Portuguese. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph AE, Bantock PR. Measuring potential physical accessibility to general practitioners in rural areas: a method and case study. Social Science & Medicine. 1982;34:735–746. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90428-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph AE, Phillips DR. Accessibility and utilization: Geographical perspectives on health care delivery. London: Harper & Row Ltd. 1984 [Google Scholar]

- Kenagy JW, Berwick DM, Shore MF. Service quality in health care. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281:661–665. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.7.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovett A, Haynes R, Sunnenberg G, Gale S. Car travel time and accessibility by bus to general practitioner services: a study using patient registers and GIS. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55:97–111. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00212-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W, Qi Y. An enhanced two-step floating catchment area (E2SFCA) method for measuring spatial accessibility to primary care physicians. Health & Place. 2009;15:1100–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W, Wang F. Measure of spatial accessibility to healthcare in a GIS environment: synthesis and a case study in the Chicago region. Environmental and Planning B. 2003;30:865–884. doi: 10.1068/b29120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W, Whippo T. Variable catchment sizes for the two-step floating catchment area (2SFCA) method. Health & Place. 2012;18(4):789–795. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin TC. Women’s education and fertility: results from 26 demographic and health surveys. Studies in Family Planning. 1995;26(4):187–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D, Jordan H, Roderick P. Taking the bus: incorporating public transport timetable data into healthcare accessibility modelling. Environment and Planning A. 2008;40:2510–2525. [Google Scholar]

- McGrail MR, Humphreys JS. Measuring spatial accessibility to primary care in rural areas: improving the effectiveness of the two-step floating catchment area method. Applied Geography. 2009;29:533–541. [Google Scholar]

- Meade M, Emch M. Medical geography. 3rd The Guilford Press; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health . National survey of HIV/AIDS prevalence, behavioral risks, and information (INSIDA), 2009. Ministry of Health; Maputo, Mozambique: 2010. Final report. in Portuguese. [Google Scholar]

- Nemet GF, Bailey AJ. Distance and health care utilization among the rural elderly. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;50:1197–1208. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00365-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold KB, Willinsky J. Providing family planning and reproductive healthcare to Canadian immigrants: perceptions of healthcare providers. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2009;11(4):369–382. doi: 10.1080/13691050802710642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noor AM, Zurovac D, Hay SI, Ochola SA, Snow RW. Defining equity in physical access to clinical services using geographical information systems as part of malaria planning and monitoring in Kenya. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2003;8(10):917–926. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01112.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obare F, van der Kwaak A, Birungi H. Factors associated with un-intended pregnancy, poor birth outcomes and post-partum contraceptive use among HIV-positive female adolescents in Kenya. BMC Women’s Health. 2012;12:34. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-12-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Openshaw S. The modifiable areal unit problem. Geo Books; Norwich: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrach B. “Yo No Sabía.” e immigrant women’s use of national health systems for reproductive and abortion care. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2013;15:262–272. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9680-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlish CL, Noor S, Brandt J. Somali immigrant women and the American health care system: discordant beliefs, divergent expectations, and silent worries. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71(2):353–361. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penchansky R, Thomas JW. The concept of access: definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Medical Care. 1981;19(2):127–140. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198102000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry B, Gesler W. Physical access to primary healthcare in Andean Bolivia. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;50:1177–1188. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00364-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman MH, Mosley WH, Ahmed S, Akhter HH. Does service accessibility reduce socioeconomic differentials in maternity care seeking? Evidence from rural Bangladesh. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2008;40(1):19–33. doi: 10.1017/S0021932007002258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riyami AA, Afifi M, Mabry RM. Women’s autonomy, education and employment in Oman and their influence on contraceptive use. Reproductive Health Matters. 2004;12(23):144–154. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(04)23113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosero-Bixby L. Spatial access to health care in Costa Rica and its equity: a GIS-based study. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;58(7):1271–1284. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton G. Public health, GIS, and spatial analytic tools. Annual Review of Public Health. 2003;24:43–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.24.012902.140843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuurman N, Berube M, Crooks VA. Measuring potential spatial access to primary health care physicians using a modified gravity model. Canadian Geographer. 2010;54:29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Stock R. Distance and the utilization of health facilities in rural Nigeria. Social Science & Medicine. 1983;17:563–570. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanser F, Gijsbertsen B, Herbst K. Modelling and understanding primary health care accessibility and utilization in rural South Africa: an exploration using a geographical information system. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63(3):691–705. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SA, Cronin JJ. Modeling patient satisfaction and service quality. Journal of Health Care Marketing. 1994;14(1):34–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller L, Gotway C. Applied spatial statistics for public health data. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wang F. Measurement, optimization and impact of healthcare accessibility: a methodological review. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2012;102(5):1104–1112. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2012.657146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Luo W. Assessing spatial and nonspatial factors in healthcare access in Illinois: towards an integrated approach to defining health professional shortage areas. Health & Place. 2005;11:131–146. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DP, Blower S. How far will we need to go to reach HIV-infected people in rural South Africa? BMC Medicine. 2007;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J, Murray AT, Agadjanian V, Hayford SR. Geographic influences on sexual and reproductive health service utilization in rural Mozambique. Applied Geography. 2012;32(2):601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]