Abstract

Acute hepatic necrosis was diagnosed in a dog. Gram staining and fluorescence in situ hybridization identified Salmonella enterica in the liver, subsequently confirmed as S. enterica serotype I 4,5,12:−:1,2. This is the first report of acute hepatic necrosis with liver failure caused by Salmonella in a dog.

CASE REPORT

A 6-month-old, fully vaccinated, female, entire Staffordshire bull terrier was presented for examination with a history of 2 days of vomiting, loose stools, lethargy, and reduced appetite. Clinical examination was unremarkable, the dog appeared in good condition and was not dehydrated, the temperature was normal, and the animal was very bright and responsive. A decision was made to give standard-dose subcutaneous injections of maropitant and ranitidine plus a bland diet of chicken and rice. The dog was always fed with a commercial dry diet.

The dog was reexamined after 4 days, and the owner reported improvement with no vomiting. However, the dog still had a reduced appetite and loose stools. Mucous membrane coloration and body temperature were not recorded. Blood work was offered, but the owner declined for financial reasons.

Two days later, during the night, the dog deteriorated very quickly, with marked lethargy, vomiting, and diarrhea. The dog was brought to the emergency service. The patient appeared very lethargic and mildly dehydrated with severe icterus. Biochemistry and a complete blood count showed severely increased liver enzymes, i.e., an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level of 1,493 (range, 23 to 212) U/liter, an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 969 (10 to 100) U/liter, a total bilirubin (TBil) level of 182 (0 to 15) μmol/liter, and a decreased urea level of 0.9 (2.5 to 9.6) mmol/liter. Hematology showed that the white blood cell count was mildly increased at 17.7 (6 to 10.9) × 109/liter with a granulocyte count of 15.6 (3.3 to 12) × 109/liter. Symptomatic treatment with standard doses of maropitant and clavulanate-potentiated amoxicillin were given subcutaneously, and fluid therapy was started.

On the following day, a physical examination showed continued severe icterus. No dehydration was reported, the body temperature was normal, and abdominal palpation and auscultation were unremarkable. Also, an abdominal ultrasound was largely unremarkable, with the liver reported as normal in size with a slightly hyperechoic appearance. Blood was taken for Leptospira antigen PCR and was found to be negative. Symptomatic treatment and fluid therapy were continued.

On the next day, the biochemistry results showed an increase in liver enzymes, i.e., an ALT level of 1,455 (normal range, 5 to 60) U/liter, an ALP level of 1,909 (≤130) U/liter, a TBil level of 225.5 (0 to 15) μmol/liter, and a cholesterol level of 9.80 (3.2 to 6.2) μmol/liter, while the urea level remained low at 2.1 (2.5 to 9.6) mmol/liter. An extensive discussion with the owner was undertaken to rule out any possible cause of intoxication. The owner confirmed that there was no possibility of mushroom ingestion and the dog was walked daily by a beach. The possibility of intoxication with green-blue algae (Microcystis aeruginosa) was ruled out because there was no ground water by the beach. Possible ingestion of hepatotoxic drugs was also ruled out by the owner. Interestingly, the owner reported the accidental ingestion of a rotten raw egg that was found during the daily walk a few days previously. Unfortunately, despite aggressive fluid therapy and symptomatic treatment, the dog developed hepatic encephalopathy with seizures and was euthanized the day after hospitalization.

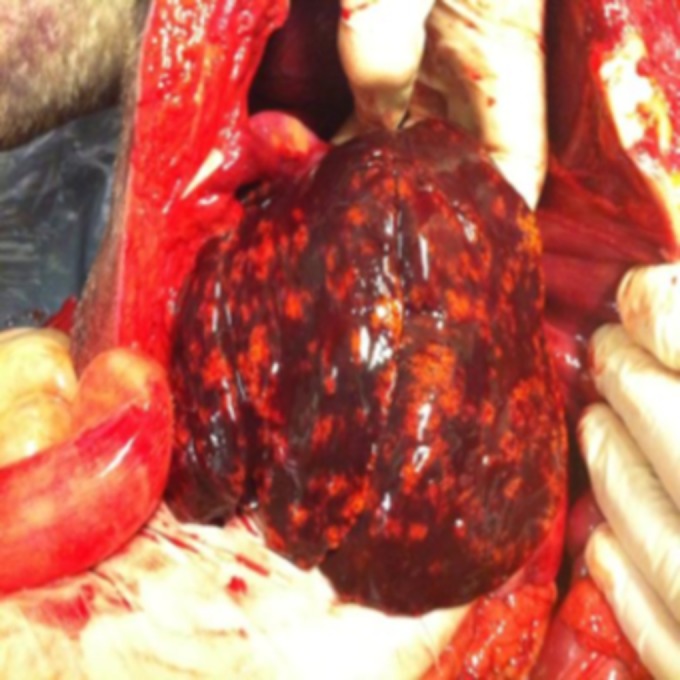

The owner gave permission for a postmortem to be performed in order to determine the cause of death. An incision along the linea alba from the xiphoid process of the sternum to the pubic area was made to expose the abdominal cavity. The liver was abnormal in color, with a diffuse dark hemorrhagic appearance (Fig. 1). A liver sample for culture was taken, and another sample was sent for histopathologic evaluation. Considering the history of vomiting, but despite the normal appearance, a sample for histopathologic evaluation was taken from the stomach and small intestine as well. The rest of the abdomen appeared normal. The chest cavity was opened. The lungs and heart were checked, and no signs of abnormality were seen. Hemorrhage in the thymus was noticed, so a sample was taken for histopathologic evaluation.

FIG 1.

Necroscopy of the liver showing a macroscopic appearance of acute liver necrosis.

The histopathologic report on the liver was diagnostic of acute hepatic necrosis. The pathologist described areas of severe and diffuse liver necrosis, with only some normal hepatocytes present in the portal areas associated with fatty change. Inflammatory infiltrates of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells were present with multifocal areas of cholestasis. Multifocal areas of hemorrhage were also present. The stomach was histologically normal. The thymus was histologically normal, except for multifocal areas of hemorrhage. The pathologist, after reevaluation with other pathologists, found no evidence of infectious canine hepatitis virus, as no viral inclusions were seen. The intestine and stomach were normal on histopathologic evaluation, and culture was not performed.

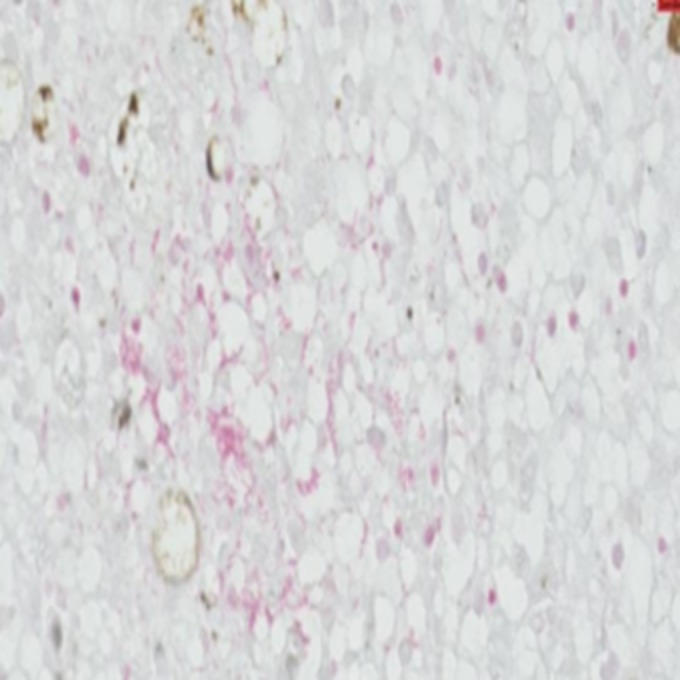

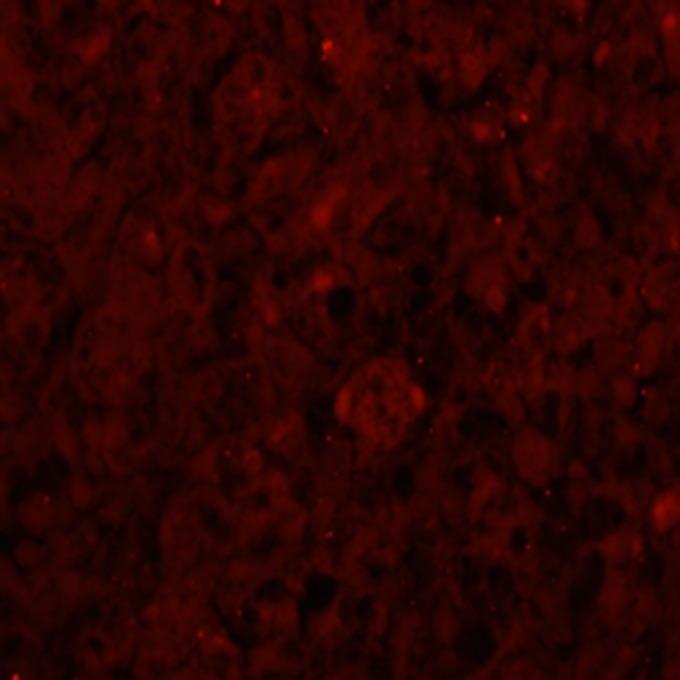

Toxicologic examination of the dog food biscuits eaten by the dog in the previous couple of weeks was performed, and the sample was found to be negative for aflatoxin. The microbiology report from the liver isolated the presence of group B Salmonella enterica sensitive to the eight most common antibiotics used in veterinary medicine. Bacteria were subsequently cultured by an enrichment technique and evaluated. The result showed the presence of monophasic, Typhimurium-like S. enterica serotype I 4,5,12:−:1,2. Further Gram staining of the liver tissue showed the presence of Gram-negative bacteria diffusely within the parenchyma (Fig. 2) colocated with the necrosis, and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) confirmed the bacteria to be S. enterica (Fig. 3).

FIG 2.

Gram staining of a section of the liver showing a small number of localized areas highlighting Gram-negative bacteria morphologically compatible with S. enterica (scale bar, 20 μm; magnification, ×600). This photo was taken with Philips Digital Image System.

FIG 3.

Section of liver analyzed by FISH and showing S. enterica in the liver parenchyma.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of acute hepatic necrosis in a dog caused by S. enterica serotype I 4,5,12:−:1,2. This Salmonella serotype is rarely isolated in human infections, but the real pathogenic and zoonotic risks are unknown. The possibility of another, unknown, etiology for the acute hepatic necrosis in this case was considered, but many other causes were ruled out and the positive culture and FISH result make Salmonella bacteria the most likely cause.

In human medicine, S. enterica serovar Typhi has been reported to cause hepatic liver enzyme increases with various degrees of liver impairment (1). This is usually due to typhoid fever, a generalized multisystemic illness with fever. In rare human cases, jaundice and severe hepatitis have been described as complications of infection with S. Typhi (1, 2). In this infection, the liver histopathologic evaluation usually shows mononuclear cell infiltration with focal minimal portal tract infiltration and areas of focal necrosis (1, 2). The mechanism by which S. Typhi causes hepatitis is unclear. Extraintestinal S. enterica serovar Typhimurium infections have occasionally been reported in children under 5 years old and in immunocompromised individuals (3–5). In immunocompromised patients, arthritis, osteomyelitis, and solitary or multiple abscesses in the spleen, liver, and brain have been described (5), while in children, meningoencephalitis, pericarditis, cholecystitis, and hepatitis have been reported (3).

In dogs, salmonellosis is often asymptomatic and clinical signs of infection are uncommon with severe clinical signs in young or debilitated patients (6). A previous case report described three acute cases of S. Typhimurium infection in young puppies that resulted in sudden death (7). The necroscopies of these patients revealed some areas of hepatic necrosis, but the areas of necrosis were not diffuse and did not cause liver failure, and the dogs likely died of systemic inflammation due to septicemia rather than liver failure (7). There are two case reports of young dogs with localized infection with S. Typhimurium; in one case, the bacteria were localized in the kidneys, and in the other case, the bacteria were localized in the gallbladder. The bacteria were not systemic in either case (8, 9). To our knowledge, the isolation of Salmonella serotype I 4,5,12:−:1,2 with hepatic necrosis and liver failure has never been described previously.

In this case report, it is possible that the Salmonella bacteria isolated caused the mild symptoms of illness during the first week of infection, with very mild signs of vomiting and diarrhea, later causing septicemia with a poor host response, considering the young age of the dog. Unfortunately, a blood culture was not performed because of the previous administration of antibiotics and the lack of clinical and laboratory findings suggestive of septicemia (e.g., fever and disseminated intravascular coagulation). Therefore, septicemia cannot be confirmed or ruled out completely. The lack of fever could be due to the prompt injection of antibiotics, or it is possible that there was fever but it was transient and not picked up at the time of the clinical examination. The culture and sensitivity showed that the Salmonella bacteria isolated were sensitive to the previously administered amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, with a MIC of ≤2 (reference range, 2 to 32) μg/ml. Despite that, considering the isolation of the bacteria in the liver tissue, it is possible that the administration of the antibiotic could not reach the necessary concentration to affect the growth of the bacteria. Furthermore, antibiotic treatment could have been detrimental rather than protect from the bacterial infection. For example, it has recently been shown that mice infected with S. Typhimurium and treated with antibiotics have not only higher concentrations of fecal Salmonella bacteria but also greater morbidity and mortality than non-antibiotic-treated mice (10).

Bile culture has been found to be more sensitive than liver tissue culture in the detection of bacteria, but bile culture was not performed in this case. The finding of a positive culture in liver tissue indicated the presence of Salmonella bacteria, and the positive FISH for the bacteria in the liver parenchyma confirmed this finding. Culture of feces was not performed because no obvious signs of small intestinal pathology could be seen clinically or on histopathologic examination.

The possibility of toxin exposure was extensively discussed with the owner after the histopathology report. The owner described the dog as a fussy eater, with no scavenging behavior, and ruled out any exposure to fungal toxins or Microsporum fungi. The owner did not have a garden, and living by the sea, the daily walk was beside the beach. Considering the hostile environment of the beach by the sea for mushroom growth, the occurrence of toxic mushroom ingestion was considered very improbable. Furthermore, the absence of a pond ruled out the possibility of Microcystis aeruginosa alga ingestion. The possibility of ingestion of any kind of drugs was ruled out by the owner. Infectious hepatitis was ruled out by the pathologist, who could not see any inclusion bodies specific to the disease, and the dog was regularly vaccinated.

Considering the dog's history, the isolation of S. enterica serotype I 4,5,12:−:1,2 in acute liver failure with necrosis makes this case interesting and highlights the need to consider this in liver disease in canine patients where no other cause is evident.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kamath PS, Jalihal A, Chakraborty A. 2000. Differentiation of typhoid fever from fulminant hepatic failure in patients presenting with jaundice and encephalopathy. Mayo Clin Proc 75:462–466. doi: 10.4065/75.5.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kadhiravan T, Wig N, Kapil A, Kabra SK, Renuka K, Misra A. 2005. Clinical outcomes in typhoid fever: adverse impact of infection with nalidixic acid-resistant Salmonella typhi. BMC Infect Dis 5:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-5-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee WS, Puthucheary SD, Parasakthi N. 2000. Extra-intestinal non-typhoidal Salmonella infections in children. Ann Trop Paediatr 20:125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manckoundia P, Popitean L, Martin I, Pfitzenmeyer P. 2005. Acute nephropathy due to Salmonella typhimurium septicaemia. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20:244–245. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon MA. 2008. Salmonella infections in immunocompromised adults. J Infect 56:413–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter ME, Quinn PJ. 2000. Salmonella infections in dogs and cats, p 231–244. In Wray C, Wray A (ed), Salmonella in domestic animals. CABI Publishing, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson H, Wright NG. 1969. Canine salmonellosis. J Small Anim Pract 10:579–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.1969.tb03992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crow SE, Lauerman LH, Smith KW. 1976. Pyonephrosis associated with Salmonella infection in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 169:1324–1326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Timbs DV, Durham PJK, Barnsley DGC. 1974. Chronic cholecystitis in a dog infected with Salmonella typhimurium. N Z Vet J 22:100–102. doi: 10.1080/00480169.1974.34142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gopinath S, Lichtman JS, Bouley DM, Elias JE, Monack DM. 2014. Role of disease-associated tolerance in infectious superspreaders. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:15780–15785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409968111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]