Abstract

Apical cAMP-dependent CFTR Cl− channels are essential for efficient vectorial movement of ions and fluid into the lumen of the colon. It is well known that Ca2+-mobilizing agonists also stimulate colonic anion secretion. However, CFTR is apparently not activated directly by Ca2+, and the existence of apical Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels in the native colonic epithelium is controversial, leaving the identity of the Ca2+-activated component unresolved. We recently showed that decreasing free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]) within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) lumen elicits a rise in intracellular cAMP. This process, which we termed “store-operated cAMP signaling” (SOcAMPS), requires the luminal ER Ca2+ sensor STIM1 and does not depend on changes in cytosolic Ca2+. Here we assessed the degree to which SOcAMPS participates in Ca2+-activated Cl− transport as measured by transepithelial short-circuit current (Isc) in polarized T84 monolayers in parallel with imaging of cAMP and PKA activity using fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based reporters in single cells. In Ca2+-free conditions, the Ca2+-releasing agonist carbachol and Ca2+ ionophore increased Isc, cAMP, and PKA activity. These responses persisted in cells loaded with the Ca2+ chelator BAPTA-AM. The effect on Isc was enhanced in the presence of the phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitor 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), inhibited by the CFTR inhibitor CFTRinh-172 and the PKA inhibitor H-89, and unaffected by Ba2+ or flufenamic acid. We propose that a discrete component of the “Ca2+-dependent” secretory activity in the colon derives from cAMP generated through SOcAMPS. This alternative mode of cAMP production could contribute to the actions of diverse xenobiotic agents that disrupt ER Ca2+ homeostasis, leading to diarrhea.

Keywords: FRET imaging, cAMP, anion secretion, endoplasmic reticulum, colonic epithelium

apical cl− channels are essential for maintaining hydration of the luminal contents of the intestine. Pathological imbalance of this process commonly results in intestinal disorders including obstruction and diarrhea. In the colon, the secretion of anions (Cl− and, to a smaller extent, HCO3−) occurs mainly at the level of the cells of the colonic crypt to create the osmotic gradient necessary to attract water into the lumen. This process is under the physiological control of various neurotransmitters, endocrine, paracrine, and immune mediators. These diverse agents typically converge on two fundamental intracellular signaling systems, cAMP and Ca2+, to orchestrate the cooperative activity of channels, pumps, and transporters needed for efficient electrolyte and fluid secretion (1).

The tremendous synergism observed when colonic cells are stimulated concurrently by both cAMP and Ca2+ has been known for years (18, 35), but details of this process are still not completely understood. There is extensive reciprocal modulation at the level of individual messenger pathways (cAMP-Ca2+ “cross talk”) in colon, as in all cells (25, 55, 56), and this profoundly affects the secretory response (6).

In colonic cells, the dominant Cl− exit pathway is the apical cAMP-dependent cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR), although expression of other Cl− pathways (e.g., ClC-2) has also been suggested (15). Intracellular uptake of Cl− is mediated mainly by the basolateral Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter. Ca2+- and cAMP-activated K+ channels (37) provide the driving force for the secretion of Cl− and other anions by maintaining a hyperpolarized membrane voltage (7, 17, 22, 23, 30). Ca2+-activated Cl− channels (CaCCs) such as TMEM16A are clearly involved in anion secretion in many types of epithelia but might not necessarily constitute a major pathway in colon (41). Therefore, it appears that some component of cAMP-dependent Cl− secretion is likely needed to initiate efficient vectorial transport of ions in the colon.

Recently we described a new mode for eliciting elevations in intracellular cAMP that is triggered directly by a decrease in free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]) within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ store. We termed this process “store-operated cAMP signaling” (SOcAMPS) (33). SOcAMPS is completely independent of cytosolic [Ca2+], requires the luminal ER Ca2+ sensor STIM1 (stromal interaction molecule), and is particularly prominent in NCM460 cells, colon-derived cultured cells of epithelial origin (34, 40, 44). The same mechanism was also described in other Cl− secretory cells, CFTR-expressing airway epithelia (47), and in cholangiocytes (49). The physiological importance of SOcAMPS in the native colon is unknown, but such a pathway would be expected to permit Ca2+-mobilizing agents that persistently deplete the ER Ca2+ store to generate cAMP, which in turn would stimulate cAMP-dependent ion transport processes (i.e., via CFTR), leading to fluid secretion that is independent of cytosolic [Ca2+].

In this work we investigated whether SOcAMPS has functional consequences in colonic cells. To this end, we took advantage of newer-generation fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based sensors to measure cAMP and PKA activation dynamics in single T84 cells, a human colonic adenocarcinoma cell line, and correlated these measurements with Cl− secretion evaluated with classical short-circuit current (Isc) techniques. We found that depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores by a variety of agents in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ initiates cAMP/PKA signaling, and thereby elicits a measurable functional secretory response. We propose that this store depletion-dependent PKA activation assists in driving the increase in Cl− secretion observed upon mobilization of Ca2+ stores via the Ca2+/phosphoinositide pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and solutions.

Reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) with the following exceptions: 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid AM ester (BAPTA-AM), fura-2 AM, and N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis-(2-pyridylmethyl)-ethylenediamine (TPEN) (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY); ionomycin, KT5720, and H-89 hydrochloride (EMD Chemicals, Billerica, MA); and CFTRinh-172 (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI). These reagents were stored as 1,000× stock solutions in either dimethyl sulfoxide or water.

Ca2+-free bicarbonate-buffered Ringer solution contained (in mM) 120 NaCl, 2.09 K2HPO4, 0.34 KH2PO4, 24 NaHCO3, 1 MgSO4, and 10 d-glucose. One millimolar CaCl2 was added to Ca2+-containing Ringer solution. HEPES-buffered solution contained 125 NaCl, 10 HEPES, 2.4 K2HPO4, 0.39 KH2PO4, 1 MgSO4, and 10 d-glucose, pH 7.43. In solutions containing Ba2+, MgCl2 was substituted for MgSO4.

Cell culture and transfection.

T84 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells plated on glass coverslips were transiently transfected with FRET-based cAMP, Ca2+, or PKA activity sensors with FuGENE transfection reagent (Promega) 24–48 h prior to imaging. For Isc measurements, cells were plated 14–21 days prior to experiments on 1.12-cm2 Snapwell inserts with a pore size of 0.4 μm (Corning, NY) at a density of ∼1.5E5 cells/well. When FRET imaging was performed with Snapwells, cells were transfected with sensors prior to seeding and used when high-resistance monolayers formed, as for the Isc experiments.

Experiments with rat colon.

Distal or proximal colon segments, harvested from adult male Sprague-Dawley rats euthanized by CO2, were opened along the mesenteric line and rinsed with ice-cold saline. Colonic segments were dissected from submucosa and muscular layers and mounted in a six-pin circular aperture slider (8-mm diameter; Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, CA) for use in Isc experiments. Experimental protocols were approved by the VA Boston Healthcare System Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Short-circuit current measurements.

Ussing chambers (Physiologic Instruments) were mounted with Snapwell inserts containing either confluent T84 cells or segments of rat colon and bathed in 3.5 ml/well of bicarbonate-buffered solution gassed with 95% O2-5% CO2 at 37°C. Isc was measured with a VCC MC6 multichannel I/V clamp (Physiologic Instruments), and data were recorded and analyzed with PowerLab 4/30 (AD Instruments, Castle Hill, Australia). All solutions were added symmetrically to both sides of the Ussing chamber, unless otherwise noted.

Live cell imaging protocols.

Glass coverslips were mounted in a perfusion chamber (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) that enabled laminar flow of HEPES-buffered Ringer solution. Ratio images were recorded on a TE2000-U microscope using a ×40 (1.3 NA) or ×60 (1.45 NA) oil-immersion objective lens. Images were taken every 5–10 s during the time-lapse capture. Excitation and emission filter wheels (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) were controlled with MetaFluor software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). This allowed excitation of the FRET-based sensors with 440-nm excitation light and measurement of a 480 nm-to-535 nm FRET emission ratio for the cAMP sensors (EpacH30 or EpacH90; a kind gift of Kees Jalink, Netherlands Cancer Institute) (43, 53) and a 535 nm-to-480 nm FRET emission ratio for A-Kinase Activity Reporter 4 (AKAR4) (kindly provided by Jin Zhang, Johns Hopkins University) (16) and the Ca2+ sensor D3cpv (42). For fura-2 imaging of Ca2+, cells were first incubated with 1.5–2.5 μM fura-2 AM in DMEM for 30 min at 37°C. Fura-2 fluorescence was measured in 340/385-nm excitation mode (510-nm emission). For experiments using BAPTA-AM and fura-2 AM, cells were coloaded with both compounds as above.

Data analysis and statistics.

Values are expressed as means ± SE for n individual experiments. The significance of the observations was evaluated by Student's t-test for paired or unpaired data as appropriate, and P < 0.05 denotes a statistical difference.

RESULTS

ER Ca2+ store depletion induces measurable anion secretion in T84 monolayers in the absence of external Ca2+.

Agents that elevate intracellular cAMP such as the adenylyl cyclase (AC) activator forskolin are well established to stimulate changes in anion secretion, also in the absence of extracellular Ca2+. As demonstrated in Fig. 1A, addition of forskolin to T84 monolayers bathed bilaterally in nominally Ca2+-free solutions produced changes in Isc that were largely reversed by treatment with the CFTR inhibitor CFTRinh-172 and further reversed by the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter inhibitor bumetanide.

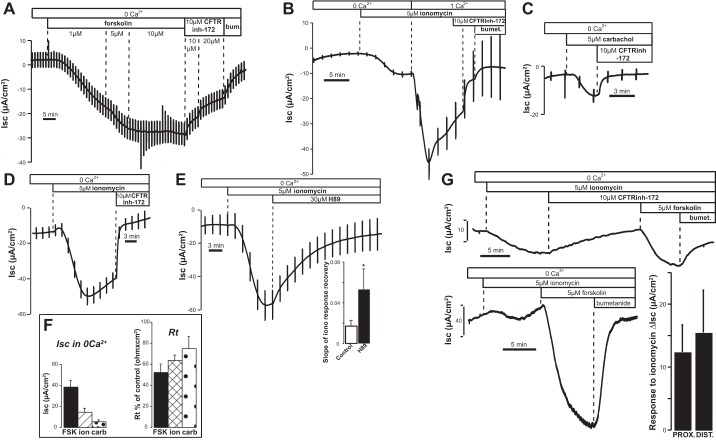

Fig. 1.

Short-circuit current (Isc) response to forskolin and ionomycin in the absence of external Ca2+ in T84 monolayers and colonic epithelium. A: response to forskolin in the absence of Ca2+ and reversal by the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) inhibitor CFTRinh-172 and bumetanide. The deflections in the traces are due to transepithelial current pulses applied to measure transepithelial resistance (Rt). B: response to ionomycin compared in Ca2+-free solutions and after acute addition of Ca2+. C and D: carbachol (C) and ionomycin (D) stimulate a significant CFTRinh-172-sensitive Cl− secretion in the absence of external Ca2+. E: PKA inhibitor H-89 significantly accelerated the recovery of the response to ionomycin in Ca2+-free solutions. Bar graph summarizes results. *P = 0.033 compared with controls done in parallel on the same day (control: n = 11, H-89: n = 5). F, left: summary of results obtained with forskolin (FSK; n = 13, P < 0.0001), ionomycin (ion; n = 23, P = 0.00023), and carbachol (carb; n = 7, P = 0.0018). Right: Isc responses were accompanied by significant changes in Rt (forskolin P = 0.016; ionomycin P < 0.0001; carbachol P = 0.027). G: changes in Isc following ionomycin (top) and forskolin (bottom) treatment in Ca2+-free solutions in rat proximal colonic epithelium. Note that the subsequent change in Isc following addition of forskolin in the presence of CFTRinh-172 (top) was greatly reduced compared with the control response (bottom). Bar graph summarizes the responses to ionomycin (ΔIsc) obtained in proximal (n = 11) and distal (n = 5) rat colon.

It is also well established that maneuvers that mobilize internal Ca2+ stores to elevate intracellular [Ca2+] are able to induce significant Cl− secretion in colonic cells (3, 5, 14, 19, 21, 46, 50). Release of ER Ca2+ stores with agonists or ionophores typically causes a transient increase in intracellular Ca2+. The corresponding reduction in free intraluminal ER [Ca2+] then stimulates store-operated Ca2+ entry pathways in the plasma membrane (2, 10, 48). This leads to a second phase of sustained Ca2+ influx that is terminated only upon store refilling. As shown in Fig. 1B, ionomycin caused a small but significant increase in basal Isc when added in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (observed in 19/24 monolayers). Readdition of Ca2+ produced a large increase in Isc that was partially sensitive to CFTRinh-172 and fully terminated by bumetanide. Of note, acute addition of CFTRinh-172 by itself had no effect on Isc (not shown). These results confirm previous findings that Ca2+ entry strongly enhances Isc across T84 monolayers. However, we were struck by the persistent nature of the small initial increase in Isc in Ca2+-free Ringer solution, as it frequently did not mirror the expected time course of the transient Ca2+ release phase of the signal. As seen in Fig. 1B, the response in Ca2+-free solutions was fully reversed by CFTRinh-172 and amounted to ∼40% of the Isc change induced by 5 μM forskolin under the same conditions (see Fig. 1A for comparison and Fig. 1F for data summary). A small but significant increase in Isc was also obtained upon addition of the cholinergic Ca2+ mobilizing agonist carbachol (Fig. 1C).

As expected, these increases in Isc were accompanied by a proportional decrease in transepithelial resistance (Rt;, summarized in Fig. 1F, right), indicating an increase in the transepithelial conductance. Interestingly, acute addition of the PKA inhibitor H-89 resulted in a fast reversal of ionomycin-induced anion secretion (Fig. 1E), consistent with a cAMP/PKA-mediated action of the ionophore. Overall, the data of Fig. 1 suggest that there is a small but sustained Isc elicited by maneuvers that empty ER Ca2+ stores in the absence of extracellular Ca2+. This effect was inhibited by H-89 and CFTRinh-172, leaving open the possibility that the action of ionomycin is in part mediated via PKA-dependent stimulation of CFTR. The finding that a detectable anion flux can be elicited by store depletion in the absence of external Ca2+ seems to also hold true for the native tissue, since we observed similar results in both proximal and distal rat colon (Fig. 1G).

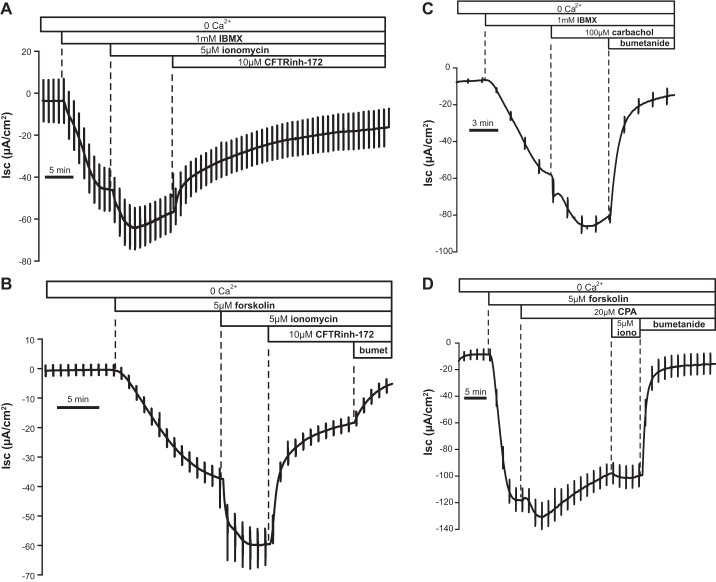

It is known that changes in Isc elicited by ionomycin or other Ca2+ store-depleting agents in T84 cells can be amplified in the face of elevated cytosolic cAMP (35). We tested whether this is also the case in Ca2+-free conditions. Figure 2 shows the significant effect of ionomycin after pretreatment with the general phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitor IBMX (1 mM; Fig. 2A) or when measured after pretreatment with a submaximal dose of forskolin (Fig. 2B). In both cases the increase in Isc induced by ionomycin was significantly higher than that evoked by ionomycin alone. Similar results were obtained with carbachol (Fig. 2C) or the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) pump inhibitor cyclopiazonic acid (CPA; Fig. 2D). As expected, a much smaller effect was observed when the ionophore was administered after internal Ca2+ stores had already been partially emptied by CPA (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Isc change following store depletion in the absence of external Ca2+ was enhanced after cAMP elevation. A and B: Isc response to ionomycin after IBMX (A; −19.31 ± 1.74 μA/cm2, n = 10) and after forskolin (B; −31.85 ± 5.96 μA/cm2, n = 5); both responses were higher than ionomycin alone (−11.89 ± 2.59); the response in the presence of forskolin was significantly higher (P < 0.0001). C: the change in Isc due to carbachol in the presence of IBMX (−18.36 ± 0.11 μA/cm2, n = 3) was significantly different from the control response (−5.5 ± 1.04 μA/cm2, P < 0.0001). D: response to cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) in the presence of forskolin (−4.4 ± 1.4 μA/cm2, n = 7).

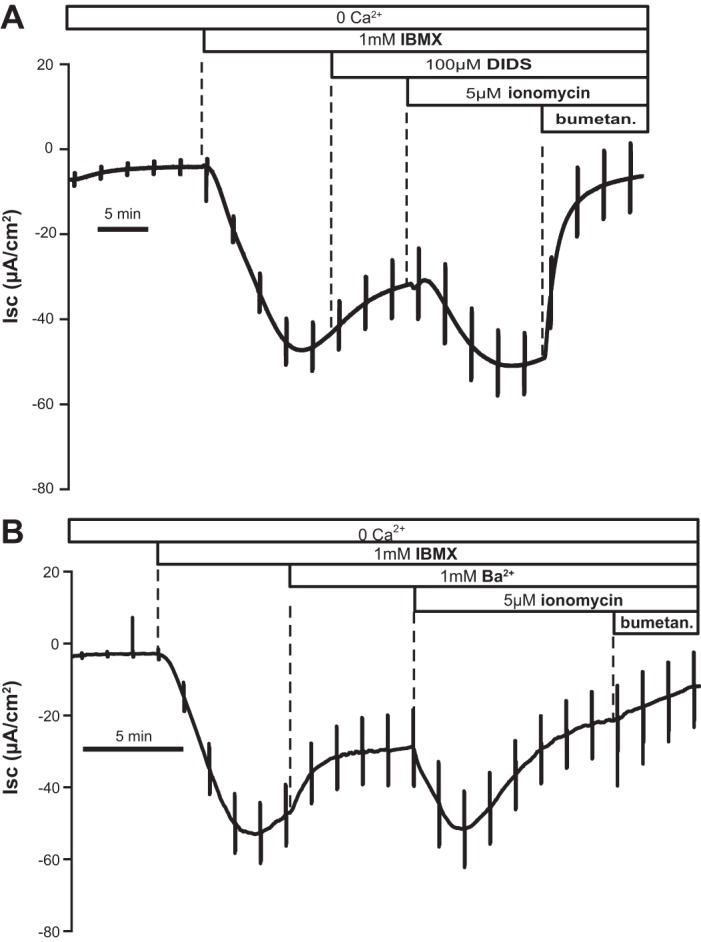

Effect of ionomycin on Isc persists after blockade of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels and other parallel ion-conducting pathways.

Even though the experiments above were conducted in Ca2+-free solutions, we considered the possibility that the transient spike of Ca2+ elicited by ionomycin or other Ca2+-releasing agents might lead to opening of CaCCs, thus accounting for the increase in Isc. However, the stilbene derivative 4,4′-diisothiocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (DIDS), a known nonspecific CaCC inhibitor (used also in T84 cells) (3, 29, 38, 52), did not eliminate the response to ionomycin, here shown in the presence of IBMX (Fig. 3A). Similar results (not shown) were also obtained with the fenamate compound flufenamic acid, another nonspecific CaCC inhibitor (45, 54). While our data do not exclude non-CFTR anion pathways in T84 cells, we do show that the response to store depletion can be maintained even when several known Cl−-conducting pathways are eliminated.

Fig. 3.

4,4′-Diisothiocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (DIDS) or Ba2+ did not inhibit the response to ionomycin. A: Isc response to ionomycin in the presence of DIDS (−12.35 ± 3.47 μA/cm2; typical of n = 5) was not significantly different from that measured in control experiments (−19.31 ± 1.74 μA/cm2, n = 28). B: response in the presence of Ba2+ after pretreatment of T84 monolayers with IBMX was also not significantly different from the control response (−34.56 ± 8.62 μA/cm2; typical of n = 7 experiments). Similar results were observed after preincubation with forskolin.

Optimal efficiency of anion flux across the colonic epithelium is obtained when there is parallel activation of K+-conducting channels, leading to membrane hyperpolarization. For example, it is known that K+ channel openers (e.g., 1-EBIO compound, which targets Ca2+-activated K+ channels) augment Cl− secretion in T84 cells (17). The initial Ca2+ spike after ionomycin might therefore activate K+ channels and indirectly enhance Isc, but the presence of the nonspecific K+ channel blocker Ba2+ in the serosal bath did not affect the change in Isc induced by ionomycin (Fig. 3B). Of note, in a limited series of experiments, we also applied K+ channel blockers to both sides of the monolayer (2 experiments with Ba2+ and 1 with flufenamic acid), with a similar lack of effect. This suggests that Ca2+-stimulated opening of basolateral K+ channels (and possibly apical channels as well) cannot account entirely for the action of ionomycin, although it is undisputed that these channels are permissive for the secretory response.

Evidence for store-operated cAMP signaling as assessed with FRET sensors in single T84 cells.

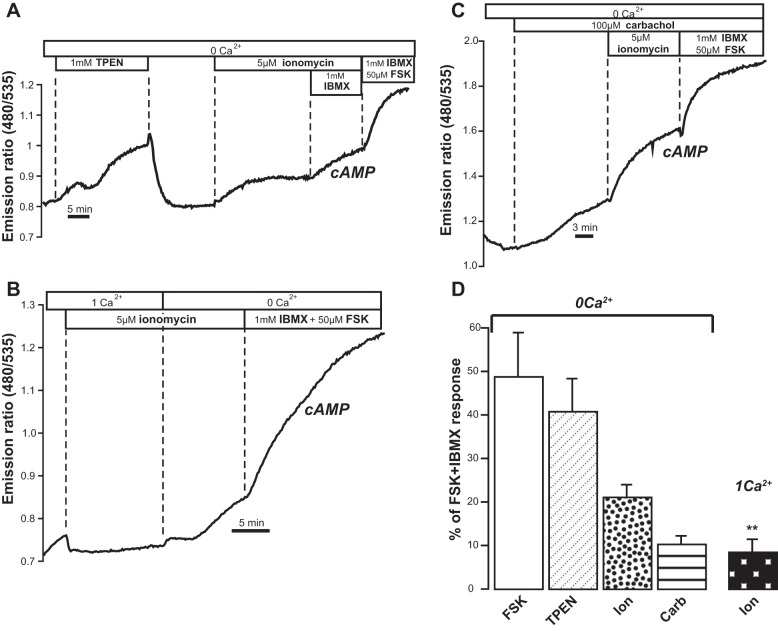

Our data indicated that Ca2+ mobilization activates an electrogenic anion conductive pathway having many features in common with CFTR. However, CFTR is generally held to require cAMP/PKA-dependent phosphorylation for its activation. One possible explanation for this residual H-89- and CFTRinh-172-sensitive Isc is that T84 cells, like several other colonic epithelial cell lines, manifest the SOcAMPS pathway such that lowering of intraluminal ER Ca2+ leads to cAMP production. This would in turn activate CFTR. We therefore assessed the effect of store depletion on cAMP levels in single T84 colonocytes, using ratiometric FRET-based cAMP sensors (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Evidence for store-operated cAMP signaling (SOcAMPS) in T84 cells. A: real-time measurements of intracellular cAMP, expressed as fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) emission ratio (480 nm/535 nm), in single T84 cells transiently transfected with the cAMP sensor EpacH30 in Ca2+-free solutions. TPEN and ionomycin increased cAMP. Supramaximal concentrations of forskolin and IBMX were given at the end of the experiments to saturate the sensor. B: removal of Ca2+ from extracellular solution enhanced cAMP production. C: carbachol and ionomycin increased cytosolic cAMP. Other cAMP FRET sensors (EpacH74 and EpacH90) were also used with similar results. D: bar graph summarizes results represented as % of the maximal (FSK+IBMX) response: forskolin (4 exp/7 cells), TPEN (9 exp/9 cells), carbachol (23 exp/32 cells), ionomycin in 0 Ca2+ (11 exp/12 cells) and in 1 mM Ca2+ (n = 6 exp/8 cells). The response recorded in 1 mM Ca2+ was significantly lower than that observed in the absence of Ca2+ (column labeled “Ion”). **P = 0.0028.

Cells grown on glass coverslips were transfected with a genetically encoded cAMP reporter (either EpacH30 or EpacH90) (43, 53). To specifically manipulate intraluminal ER [Ca2+], we exposed cells to a low-affinity membrane-permeant Ca2+ buffer, TPEN. We have previously shown in other cell lines that 1 mM TPEN rapidly, reversibly, and dose-dependently lowers free [Ca2+] in the ER without affecting resting cytosolic calcium levels, also in the absence of external Ca2+ (11, 26, 33). As shown in Fig. 4A, TPEN added in Ca2+-free Ringer solution caused the 480 nm-to-535 nm FRET emission ratio of EpacH30 to gradually increase, indicating elevated cAMP concentration in the cytosol. Rinsing off TPEN fully reversed the response. Under these conditions, we expect that ER [Ca2+] should be restored to its original levels upon removal of TPEN. This would occur in the absence of Ca2+ entry across the plasma membrane because there is no Ca2+ in the bathing solution (26, 33). TPEN binds avidly to heavy metals (4, 33), but low doses (10 μM) of the chelator, expected to scavenge these other metal species, had no effect on the FRET ratio (not shown). The significant response to the subsequent addition of ionomycin is also depicted in Fig. 4A. At the end of every cAMP imaging experiment we applied a cocktail of IBMX and a supramaximal concentration of forskolin (50 μM) to establish maximal ratio response.

As illustrated in Fig. 4B, Ca2+ influx that takes place in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ attenuates SOcAMPS in T84 cells, as it does in several other cell types (33, 47, 49). Treatment with ionomycin in the presence of external Ca2+ yielded only a minor increase in the FRET ratio, but switching to a Ca2+-free solution enhanced cAMP production by ∼22%. Figure 4C also shows that the cholinergic agonist carbachol was able to induce an increase in FRET ratio, indicative of increased cAMP levels. Taken together, our data are consistent with the presence of a mechanism in which lowering of free [Ca2+] within internal Ca2+ stores can drive the production of cAMP, as shown previously in other cell types (33, 47, 49). Figure 4D summarizes the changes in cAMP (as measured by changes in the FRET ratio) obtained with forskolin alone, TPEN, ionomycin, and carbachol expressed as percentage of the maximal response to forskolin + IBMX.

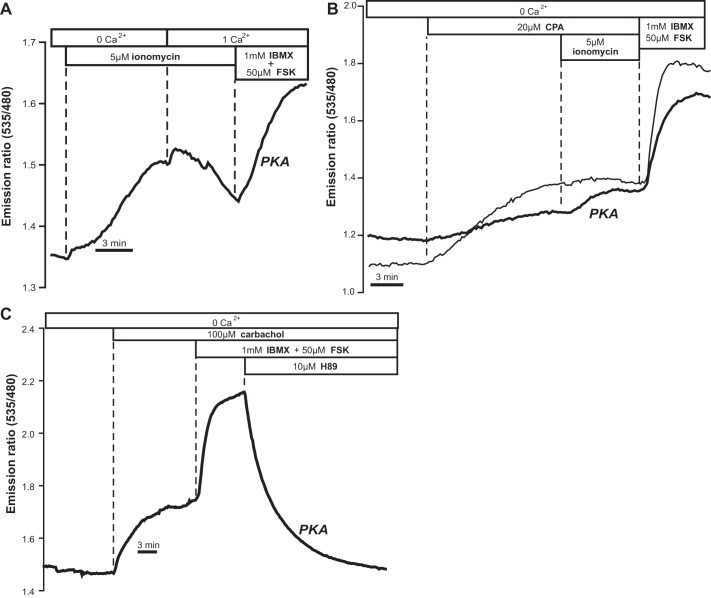

Activation of PKA in response to store depletion.

We also evaluated the effect of store depletion on signaling downstream of cAMP, using a complementary FRET-based probe for PKA activity known as AKAR4. In Fig. 5A it is shown that depleting Ca2+ stores with ionomycin resulted in an increase in the 535 nm-to-480 nm FRET emission ratio of AKAR4 in T84 cells, consistent with an increase in PKA phosphorylation. The process was inhibited when extracellular Ca2+ was readmitted to the bath.

Fig. 5.

Activation of PKA as measured by the FRET sensor A-Kinase Activity Reporter 4 (AKAR4). A: ionomycin induced PKA activity. Addition of Ca2+ inhibited this process (typical of n = 5 exp/5 cells). B: effect of the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) inhibitor CPA illustrated in 2 different cells (4 exp/4 cells). C: response to carbachol (13 exp/16 cells) was reversed by the PKA inhibitor H-89. PKA activity expressed as % of maximal (forskolin+IBMX) response: ionomycin, 72.15 ± 7.05% (5 exp/5 cells); CPA, 31.43 ± 5.32% (4 exp/4 cells); carbachol 34.08 ± 6.34% (16 exp/16 cells).

As depicted in Fig. 5, B and C, similar results were obtained when alternative strategies were used to release Ca2+ stores. In fact, both CPA (Fig. 5B) and carbachol (Fig. 5C) were able to activate PKA, as measured by AKAR4. The response could be fully reversed by the PKA inhibitor H-89 (Fig. 5C).

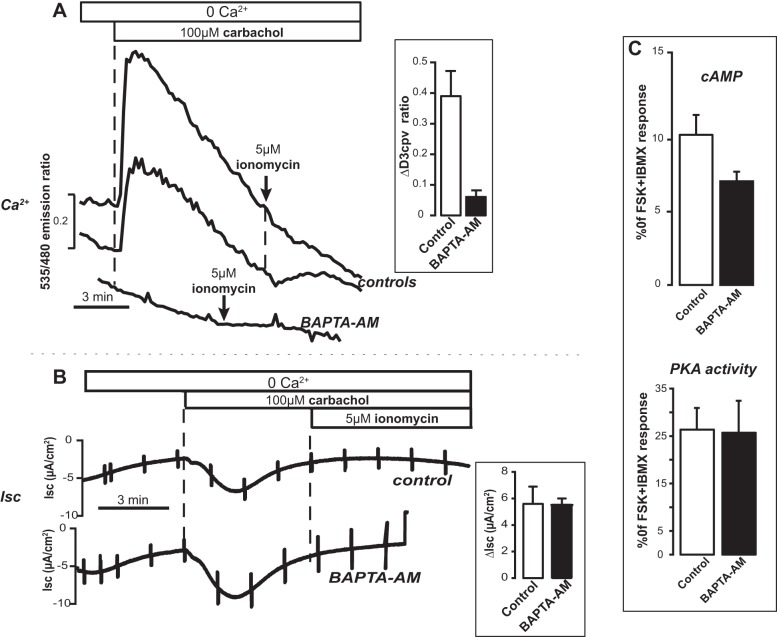

A component of Isc response in T84 monolayers is independent of cytosolic Ca2+: effect of BAPTA-AM.

Our data indicated that lowering free [Ca2+] in the ER with diverse tools led to change in Isc, cAMP production, and PKA activation. However, with the exception of the TPEN experiments, the maneuvers used to lower ER [Ca2+] imply an obligate release of Ca2+ into the cytosol. It is well established that changes in cytosolic [Ca2+] can either stimulate or inhibit cAMP production through the various Ca2+-sensitive isoforms of ACs or PDEs. Unfortunately, we could not use TPEN on the monolayers because even low concentrations caused a loss of Rt. We therefore performed experiments in which the monolayers were exposed to the high-affinity cell-permeant Ca2+ chelator BAPTA-AM, thereby clamping excursions of cytosolic free [Ca2+] following store release.

First we needed to directly assess the ability of BAPTA-AM to effectively buffer intracellular Ca2+ changes in high-resistance T84 monolayers. The diffuse background of the monolayers grown on semipermeable supports interfered with our initial attempts to monitor Ca2+ changes with fura-2. We therefore performed these control experiments with the newer-generation genetically encoded cameleon Ca2+ reporter D3cpv (42). Cells were first transfected with D3cpv, seeded onto Snapwell filters, and used when a high-resistance monolayer was formed. With this approach it was possible to locate individual cells within the monolayers that expressed the Ca2+ reporter. Figure 6A compares typical experiments in which intracellular Ca2+ changes were recorded in controls and in BAPTA-AM-preloaded monolayers. These experiments demonstrate that BAPTA-AM was highly effective in preventing cytosolic Ca2+ spikes following stimulation with carbachol or ionomycin. Parallel Isc experiments showed that the increase in Isc observed after stimulation with carbachol was independent of changes in cytosolic Ca2+ levels, as the response in cells pretreated with the intracellular Ca2+ buffer was not different from the control in Ca2+-free solutions (Fig. 6B). Imaging experiments to measure cytosolic cAMP changes and PKA activation, respectively, confirmed that BAPTA-AM preincubation did not influence the response to store depletion with carbachol (Fig. 6C). Therefore, we propose that lowering of free [Ca2+] per se within the lumen of internal stores results in cAMP production in T84 cells. This cAMP signal contributes in a small but not insignificant manner to the Isc response of the monolayer, likely through activation of PKA-dependent CFTR.

Fig. 6.

Effect of the intracellular Ca2+ buffer BAPTA-AM. A: intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]) changes, measured with cameleon D3cpv in T84 cell monolayers, in controls (top) and in cells preloaded (45 min) with 20 μM BAPTA-AM (bottom). Bar graph: the response to carbachol in BAPTA-AM-pretreated cells (12 exp/35 cells) was significantly different (P = 0.00017) from control (7 exp/35 cells). B: changes in Isc after addition of carbachol and ionomycin in control (top) and BAPTA-AM-pretreated (bottom) monolayers. Bar graph: response to carbachol was not different in control (n = 5) vs. BAPTA-AM-pretreated (n = 4) monolayers. C: FRET experiments with EpacH30 (top) and with AKAR4 (bottom) showed that cAMP and PKA activity did not change after preincubation with BAPTA-AM. EpacH30: controls 23 exp/46 cells; BAPTA-AM 7 exp/18 cells. AKAR4: controls 20 exp/25 cells; BAPTA-AM 6 exp/10 cells.

DISCUSSION

cAMP-dependent gating of CFTR is a point of convergence for the Cl− and fluid secretory activity of many epithelia. In the conventional view, cytosolic Ca2+ can potentially increase epithelial Cl− secretion by two general mechanisms: 1) by activating conductances (e.g., basolateral cation pathways and cotransporters) that are permissive for vectorial anion transport via CFTR and 2) by acting on CaCCs that appear to be located in parallel with CFTR in many cell types. However, in the case of the colon, while the first mechanism seems to be universally accepted the physiological relevance of the second scenario is controversial, and difficult to reconcile with the profound deficits in colonic secretion observed in CFTR-null models (3, 5, 7, 14, 24, 30, 35, 38, 46).

Although the powerful synergism imposed by Ca2+ and cAMP on epithelial secretory activity has been known for many years, nuances on this theme continue to emerge. Billet and Hanrahan (9) recently commented on the “secret life” of CFTR as a Ca2+-activated anion conductance. Thus while not directly gated by Ca2+, there are numerous indirect modes by which Ca2+ signaling impacts this important pathway (9, 31). For example, Ca2+ can potentially stimulate CFTR gating via tyrosine kinases and inhibit protein phosphatase type 2A to alter the termination of channel activity (9, 20). Ca2+-dependent AC has also been proposed to generate apical cAMP microdomains that positively regulate CFTR in colon (9).

Conversely, cAMP also affects Ca2+ signaling in colon in many ways. These include recently described PKA-dependent phosphorylation of IRBIT, a protein that dissociates from the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor to modify both ER Ca2+ release and ion transporters that participate in the secretory response (1, 57). CFTR inserted into the ER membrane as it traffics along to the plasma membrane may potentially affect ER Ca2+ handling and signaling upon its activation with cAMP (27, 36). In addition, stimulation of the cAMP effector Epac is known to influence PLCε activity to elicit Ca2+ signaling, also in T84 cells (28).

The fact that such a multiplicity of mechanisms, both Ca2+ and cAMP dependent, converge to activate CFTR highlights its essential role in colonic physiology. Here we provide evidence that a discrete component of Ca2+-activated Cl− secretion observed in T84 colonic cells may be partially explained by the previously described “store-operated” cAMP signaling mechanism that links lowering of free Ca2+ within stores to activation of AC (33, 34, 44) to gate cAMP-dependent CFTR. Key FRET imaging results shown in Figs. 4–6 indicate that lowering Ca2+ in ER stores with different strategies resulted in increased cAMP/PKA activity. In agreement with our previous findings in another colonic cell line (33, 34), the effects of store depletion on cAMP/PKA were actually attenuated by Ca2+ entering from the extracellular space in T84 cells. While depletion of ER Ca2+ usually implies an obligatory elevation of cytosolic Ca2+, our data obtained in BAPTA-AM- and TPEN-treated cells indicate that this effect is independent of excursions in cytosolic [Ca2+]. These data would also argue that Ca2+-activated ACs (or PDEs inactivated by Ca2+) are not responsible for the effects of store depletion on cAMP/PKA activity. This latter interpretation is also consistent with the finding that Ca2+ entry from the extracellular space attenuated rather than activated cAMP production.

As assessed by Isc experiments, the increase in cAMP/PKA activity in the absence of external Ca2+ resulted in stimulation of H-89- and CFTRinh-172-sensitive anion secretion, and this response was not affected by BAPTA-AM treatment (Fig. 6). Under these conditions, we expect any potential contribution of CaCCs to be minimized (14, 46), although we cannot exclude the existence of cytosolic “nanodomains” of Ca2+ that might not be perfectly clamped by the chelator. However, experiments with two nonspecific but effective CaCC inhibitors (flufenamic acid and DIDS; Fig. 3) would argue against this point. In light of these findings we propose that, by analogy with what we observed earlier in NCM460 cells (33), SOcAMPS has the potential to contribute to the functional secretory response in T84 cells, and possibly also in the native colon (Fig. 1G).

We do not dispute that cytosolic Ca2+ has a powerful activating effect on the overall secretory response of the monolayer (Fig. 1B), nor do our data specifically preclude the existence of CaCCs in T84 cells. However, our findings do show that the actions of Ca2+-mobilizing hormones on anion flux involve a component of cAMP production. We would suggest that this second messenger production permits secretion to occur in the complete absence of hormones that directly generate cAMP. We propose that SOcAMPS would be most pronounced after prolonged depletion of ER stores, when store-operated Ca2+ entry becomes downregulated, e.g., through Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channel inactivation (10). Interestingly, as we have already observed in another colonic cell line (33, 34), in T84 cells store-operated cAMP production is not entirely eliminated in the presence of external Ca2+ (see summary bar graph, Fig. 4D). This might be sufficient to provide a minimum level of “trigger” cAMP able to sustain the secretory response following store depletion. Another consideration is that in vivo, where extracellular volumes and diffusion are quite limited compared with the effectively infinite bath of our perfusion chamber, it is possible to generate localized depletion of external Ca2+ at the site of Ca2+ entry. We measured this directly in intact gastric epithelium (12, 13) and found that store-operated Ca2+ entry can cause [Ca2+] in the extracellular basolateral spaces to fall to ∼0.5 mM, while Ca2+ export at the apical side of the tissue experiences a corresponding increase in extracellular [Ca2+]. Thus basolateral [Ca2+] can theoretically approach the concentration at which Ca2+ entry channels cease to effectively take up Ca2+ (∼0.5 mM).

CFTR is emerging as a central organizing platform for numerous proteins in the apical membrane (31). Redundant regulation of CFTR by the store-operated cAMP pathway ensures that anion fluxes can be activated under a wide range of pathophysiological conditions. The intestine is particularly susceptible to exogenous agents (e.g., viral and bacterial toxins, bile acids) that alter second messenger levels to produce unregulated secretion (7). Many of the diverse agents (intestinal pathogens, chemotherapy drugs, bioactive dietary constituents, bile acids, inflammatory mediators, and environmental toxins) that cause diarrhea also cause the release of Ca2+ from the ER (8, 14, 24, 30, 32, 38, 39, 51). This can profoundly affect Cl− and water transport across the colonic epithelium. Activation of SOcAMPS in the colon may even be protective in the face of such pathological store depletion; by providing a certain level of “trigger” cAMP, the epithelium can still mount an effective defense to flush away such noxious agents through synergistic Ca2+/cAMP-dependent activation of the fluid secretory machinery.

GRANTS

We gratefully acknowledge support from the Harvard Digestive Diseases Center (5P30DK034854-24), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (1R21DK088197-01), and the Medical Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA-ORD 1 I01 BX000968-01), all to A. M. Hofer.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: J.M.N., I.M., J.A.-J., S.C., and A.M.H. performed experiments; J.M.N., I.M., J.A.-J., S.C., and A.M.H. analyzed data; J.M.N., I.M., J.A.-J., S.C., and A.M.H. interpreted results of experiments; J.M.N., J.A.-J., S.C., and A.M.H. drafted manuscript; J.M.N., I.M., J.A.-J., S.C., and A.M.H. edited and revised manuscript; J.M.N., I.M., J.A.-J., S.C., and A.M.H. approved final version of manuscript; I.M., S.C., and A.M.H. conception and design of research; S.C. prepared figures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahuja M, Jha A, Maleth J, Park S, Muallem S. cAMP and Ca2+ signaling in secretory epithelia: crosstalk and synergism. Cell Calcium 55: 385–393, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambudkar IS. Polarization of calcium signaling and fluid secretion in salivary gland cells. Curr Med Chem 19: 5774–5781, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson MP, Welsh MJ. Calcium and cAMP activate different chloride channels in the apical membrane of normal and cystic fibrosis epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 6003–6007, 1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arslan P, Di Virgilio F, Beltrame M, Tsien RY, Pozzan T. Cytosolic Ca2+ homeostasis in Ehrlich and Yoshida carcinomas. A new, membrane-permeant chelator of heavy metals reveals that these ascites tumor cell lines have normal cytosolic free Ca2+. J Biol Chem 260: 2719–2727, 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bajnath RB, Dekker K, Vaandrager AB, de Jonge HR, Groot JA. Biphasic increase of apical Cl− conductance by muscarinic stimulation of HT-29cl.19A human colon carcinoma cell line: evidence for activation of different Cl− conductances by carbachol and forskolin. J Membr Biol 127: 81–94, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrett KE. New ways of thinking about (and teaching about) intestinal epithelial function. Adv Physiol Educ 32: 25–34, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barrett KE, Keely SJ. Chloride secretion by the intestinal epithelium: molecular basis and regulatory aspects. Annu Rev Physiol 62: 535–572, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barro Soria R, Spitzner M, Schreiber R, Kunzelmann K. Bestrophin-1 enables Ca2+-activated Cl− conductance in epithelia. J Biol Chem 284: 29405–29412, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Billet A, Hanrahan JW. The secret life of CFTR as a calcium-activated chloride channel. J Physiol 591: 5273–5278, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cahalan MD. STIMulating store-operated Ca2+ entry. Nat Cell Biol 11: 669–677, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caroppo R, Colella M, Colasuonno A, DeLuisi A, Debellis L, Curci S, Hofer AM. A reassessment of the effects of luminal [Ca2+] on inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-induced Ca2+ release from internal stores. J Biol Chem 278: 39503–39508, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caroppo R, Gerbino A, Debellis L, Kifor O, Soybel DI, Brown EM, Hofer AM, Curci S. Asymmetrical, agonist-induced fluctuations in local extracellular [Ca2+] in intact polarized epithelia. EMBO J 20: 6316–6326, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caroppo R, Gerbino A, Fistetto G, Colella M, Debellis L, Hofer AM, Curci S. Extracellular calcium acts as a “third messenger” to regulate enzyme and alkaline secretion. J Cell Biol 166: 111–119, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cliff WH, Frizzell RA. Separate Cl− conductances activated by cAMP and Ca2+ in Cl−-secreting epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 4956–4960, 1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuppoletti J, Chakrabarti J, Tewari KP, Malinowska DH. Differentiation between human ClC-2 and CFTR Cl− channels with pharmacological agents. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 307: C479–C492, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Depry C, Allen MD, Zhang J. Visualization of PKA activity in plasma membrane microdomains. Mol Biosyst 7: 52–58, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devor DC, Singh AK, Frizzell RA, Bridges RJ. Modulation of Cl− secretion by benzimidazolones. I. Direct activation of a Ca2+-dependent K+ channel. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 271: L775–L784, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dharmsathaphorn K, Pandol SJ. Mechanism of chloride secretion induced by carbachol in a colonic epithelial cell line. J Clin Invest 77: 348–354, 1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dho S, Stewart K, Foskett JK. Purinergic receptor activation of Cl− secretion in T84 cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 262: C67–C74, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer H, Machen TE. The tyrosine kinase p60c-src regulates the fast gate of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel. Biophys J 71: 3073–3082, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuller CM, Bridges RJ, Benos DJ. Forskolin- but not ionomycin-evoked Cl− secretion in colonic epithelia depends on intact microtubules. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 266: C661–C668, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halm ST, Liao T, Halm DR. Distinct K+ conductive pathways are required for Cl− and K+ secretion across distal colonic epithelium. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 291: C636–C648, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayashi M, Wang J, Hede SE, Novak I. An intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel is important for secretion in pancreatic duct cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 303: C151–C159, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hennig B, Schultheiss G, Kunzelmann K, Diener M. Ca2+-induced Cl− efflux at rat distal colonic epithelium. J Membr Biol 221: 61–72, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hofer AM. Interactions between calcium and cAMP signaling. Curr Med Chem 19: 5768–5773, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hofer AM, Fasolato C, Pozzan T. Capacitative Ca2+ entry is closely linked to the filling state of internal Ca2+ stores: a study using simultaneous measurements of ICRAC and intraluminal [Ca2+]. J Cell Biol 140: 325–334, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hofer AM, Machen TE. Technique for in situ measurement of calcium in intracellular inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-sensitive stores using the fluorescent indicator mag-fura-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 2598–2602, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoque KM, Woodward OM, van Rossum DB, Zachos NC, Chen L, Leung GP, Guggino WB, Guggino SE, Tse CM. Epac1 mediates protein kinase A-independent mechanism of forskolin-activated intestinal chloride secretion. J Gen Physiol 135: 43–58, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kidd JF, Thorn P. Intracellular Ca2+ and Cl− channel activation in secretory cells. Annu Rev Physiol 62: 493–513, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kunzelmann K, Mall M. Electrolyte transport in the mammalian colon: mechanisms and implications for disease. Physiol Rev 82: 245–289, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kunzelmann K, Mehta A. CFTR: a hub for kinases and crosstalk of cAMP and Ca2+. FEBS J 280: 4417–4429, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laohachai KN, Bahadi R, Hardo MB, Hardo PG, Kourie JI. The role of bacterial and non-bacterial toxins in the induction of changes in membrane transport: implications for diarrhea. Toxicon 42: 687–707, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lefkimmiatis K, Srikanthan M, Maiellaro I, Moyer MP, Curci S, Hofer AM. Store-operated cyclic AMP signalling mediated by STIM1. Nat Cell Biol 11: 433–442, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maiellaro I, Lefkimmiatis K, Moyer MP, Curci S, Hofer AM. Termination and activation of store-operated cyclic AMP production. J Cell Mol Med 16: 2715–2725, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mall M, Bleich M, Schurlein M, Kuhr J, Seydewitz HH, Brandis M, Greger R, Kunzelmann K. Cholinergic ion secretion in human colon requires coactivation by cAMP. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 275: G1274–G1281, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martins JR, Kongsuphol P, Sammels E, Dahimene S, Aldehni F, Clarke LA, Schreiber R, de Smedt H, Amaral MD, Kunzelmann K. F508del-CFTR increases intracellular Ca2+ signaling that causes enhanced calcium-dependent Cl− conductance in cystic fibrosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1812: 1385–1392, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matos JE, Sausbier M, Beranek G, Sausbier U, Ruth P, Leipziger J. Role of cholinergic-activated KCa1.1 (BK), KCa3.1 (SK4) and KV7.1 (KCNQ1) channels in mouse colonic Cl− secretion. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 189: 251–258, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Merlin D, Jiang L, Strohmeier GR, Nusrat A, Alper SL, Lencer WI, Madara JL. Distinct Ca2+- and cAMP-dependent anion conductances in the apical membrane of polarized T84 cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 275: C484–C495, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morris AP, Scott JK, Ball JM, Zeng CQ, O'Neal WK, Estes MK. NSP4 elicits age-dependent diarrhea and Ca2+-mediated I− influx into intestinal crypts of CF mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 277: G431–G444, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moyer MP, Manzano LA, Merriman RL, Stauffer JS, Tanzer LR. NCM460, a normal human colon mucosal epithelial cell line. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 32: 315–317, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Namkung W, Phuan PW, Verkman AS. TMEM16A inhibitors reveal TMEM16A as a minor component of calcium-activated chloride channel conductance in airway and intestinal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 286: 2365–2374, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palmer AE, Giacomello M, Kortemme T, Hires SA, Lev-Ram V, Baker D, Tsien RY. Ca2+ indicators based on computationally redesigned calmodulin-peptide pairs. Chem Biol 13: 521–530, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ponsioen B, Zhao J, Riedl J, Zwartkruis F, van der Krogt G, Zaccolo M, Moolenaar WH, Bos JL, Jalink K. Detecting cAMP-induced Epac activation by fluorescence resonance energy transfer: Epac as a novel cAMP indicator. EMBO Rep 5: 1176–1180, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roy J, Lefkimmiatis K, Moyer MP, Curci S, Hofer AM. The omega-3 fatty acid eicosapentaenoic acid elicits cAMP generation in colonic epithelial cells via a “store-operated” mechanism. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 299: G715–G722, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schultheiss G, Frings M, Hollingshaus G, Diener M. Multiple action sites of flufenamate on ion transport across the rat distal colon. Br J Pharmacol 130: 875–885, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schultheiss G, Siefjediers A, Diener M. Muscarinic receptor stimulation activates a Ca2+-dependent Cl− conductance in rat distal colon. J Membr Biol 204: 117–127, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schwarzer C, Wong S, Shi J, Matthes E, Illek B, Ianowski JP, Arant RJ, Isacoff E, Vais H, Foskett JK, Maiellaro I, Hofer AM, Machen TE. Pseudomonas aeruginosa homoserine lactone activates store-operated cAMP and cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator-dependent Cl− secretion by human airway epithelia. J Biol Chem 285: 34850–34863, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smyth JT, Hwang SY, Tomita T, DeHaven WI, Mercer JC, Putney JW. Activation and regulation of store-operated calcium entry. J Cell Mol Med 14: 2337–2349, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spirli C, Locatelli L, Fiorotto R, Morell CM, Fabris L, Pozzan T, Strazzabosco M. Altered store operated calcium entry increases cyclic 3′,5′-adenosine monophosphate production and extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 phosphorylation in polycystin-2-defective cholangiocytes. Hepatology 55: 856–868, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 50.Tabcharani JA, Harris RA, Boucher A, Eng JW, Hanrahan JW. Basolateral K channel activated by carbachol in the epithelial cell line T84. J Membr Biol 142: 241–254, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takahashi A, Iida T, Naim R, Naykaya Y, Honda T. Chloride secretion induced by thermostable direct haemolysin of Vibrio parahaemolyticus depends on colonic cell maturation. J Med Microbiol 50: 870–878, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trucksis M, Conn TL, Wasserman SS, Sears CL. Vibrio cholerae ACE stimulates Ca2+-dependent Cl−/HCO3− secretion in T84 cells in vitro. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 279: C567–C577, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van der Krogt GN, Ogink J, Ponsioen B, Jalink K. A comparison of donor-acceptor pairs for genetically encoded FRET sensors: application to the Epac cAMP sensor as an example. PloS One 3: e1916, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.White MM, Aylwin M. Niflumic and flufenamic acids are potent reversible blockers of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels in Xenopus oocytes. Mol Pharmacol 37: 720–724, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Willoughby D, Cooper DM. Organization and Ca2+ regulation of adenylyl cyclases in cAMP microdomains. Physiol Rev 87: 965–1010, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Willoughby D, Everett KL, Halls ML, Pacheco J, Skroblin P, Vaca L, Klussmann E, Cooper DM. Direct binding between Orai1 and AC8 mediates dynamic interplay between Ca2+ and cAMP signaling. Sci Signal 5: ra29, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang D, Shcheynikov N, Muallem S. IRBIT: it is everywhere. Neurochem Res 36: 1166–1174, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]