Abstract

Objective

We report rates of re-engagement in services for individuals with serious mental illness who had discontinued services.

Methods

As part of a state quality assurance program involving continuous review of Medicaid claims and other administrative data, clinician care monitors identified 2,834 individuals with serious mental illness who were apparently in need of care but disengaged from services. The care monitors reviewed monthly updates of Medicaid claims, encouraged outreach from providers who had previously worked with identified individuals, and determined whether individuals had re-engaged in services.

Results

Re-engagement rates over a 12-month follow-up period were low, particularly for individuals who had been incarcerated or for whom no service provider was available to provide outreach.

Conclusions

Subgroups of disengaged individuals with serious mental illness have different rates of re-engagement. Active outreach by providers might benefit some, but such targeting is inefficient when the individual cannot be located.

Keywords: Medicaid, serious mental illness, administrative data, clinical indicators, adherence, re-engagement

Introduction

Individuals with serious mental illness have high rates of treatment discontinuation. Between 30–45% fail to attend initial scheduled clinic visits or routinely discontinue treatment (1–4), and fewer than 50% receive continuous treatment for 12 months (5). Inadequate follow-up is a strong predictor of inpatient readmission, homelessness, and incarceration (3,4,6,7). Evidence-based practices are available for engaging individuals who frequently discontinue services (8–10) but it is unclear how best to identify individuals who may benefit from outreach.

One approach involves examining patterns of service use for populations of individuals. From 2009 – 2011, the New York City (NYC) Mental Health Care Monitoring Initiative used Medicaid claims and other administrative data to monitor service use of defined cohorts of individuals with serious mental illness and high service needs in NYC (11). In calendar year 2010, care monitors reviewed service use for 4,314 of these individuals who met pre-defined criteria suggesting disengagement from services and confirmed that 2,388 (55%) were not receiving adequate care (11). This report describes rates of re-engagement in services for 2,834 individuals (the 2,388 mentioned above plus another 446 subsequently identified) over a 12-month period following initial determination that the individual was disengaged from care. We describe rates of re-engagement for individuals grouped according to individual characteristics and availability of outreach resources.

Methods

The monitoring and review procedures for the Care Monitoring Initiative are described elsewhere (13,14). The initiative focused on high-need Medicaid beneficiaries with serious mental illness receiving federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits. High-need cohorts were defined based upon prior service use and included individuals who: received court-ordered outpatient services at any time since NYC implemented its outpatient commitment program in 2000; received assertive community treatment or case management services in the prior 12 months; received mental health services in a state forensic prison program in the prior 5 years; or had 2 or more inpatient or emergency room stays in the prior 12 months. The cutoff periods for the 3 latter groups were identified based upon preliminary estimates of the size of each cohort and the resources available to implement reviews (the total initial high-need group included nearly 9,000 individuals).

Each month, the cohorts were updated and Medicaid claims were examined using the following “notification flags” to identify individuals potentially in need of outreach due to continued frequent psychiatric hospitalizations (2 or more hospitalizations within the previous 4 months); lack of engagement in outpatient services (no outpatient visits for a mental health or substance use disorder in the previous 4 months); or lack of adherence to psychotropic medications (no psychotropic medication prescription fills in the previous 2 months).

Project care monitors (licensed clinicians supervised by a managed care vendor the state contracted with for the initiative) spoke with providers who had previously served the individuals to determine whether the notification flags accurately identified individuals who were disengaged from services. The 2,834 individuals confirmed to be disengaged were grouped into 4 categories: provider notified of need for active outreach (provider notified – active; N= 657): for these individuals the vendor identified a mental health provider able to conduct outreach; provider notified of need for enhanced outreach (provider notified – enhanced; N= 14): these individuals were confirmed to be in the community and determined to be in need of immediate outreach to prevent a situation of potential imminent danger to self or others; incarcerated (N= 611): these individuals were confirmed to be in prison or jail at the time of review (individuals serving prison sentences longer than 3 months were not coded as disengaged in this initiative); and d) lost to care (N= 1,552): for these individuals, no provider could be identified who was able to outreach and contact the individual.

Care monitors reviewed claims data and contacted providers at least monthly for follow-up regarding disengaged individuals. An individual was coded as re-engaged in care when a provider reported that the individual was receiving mental health services that the clinician care monitor believed were appropriate to the individual’s needs. We created Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrating rates of re-engagement for the 12 months after an individual triggered a notification flag. The NYS Office of Mental Health Central Office IRB approved the project as a quality improvement activity that did not constitute research involving human subjects.

Results

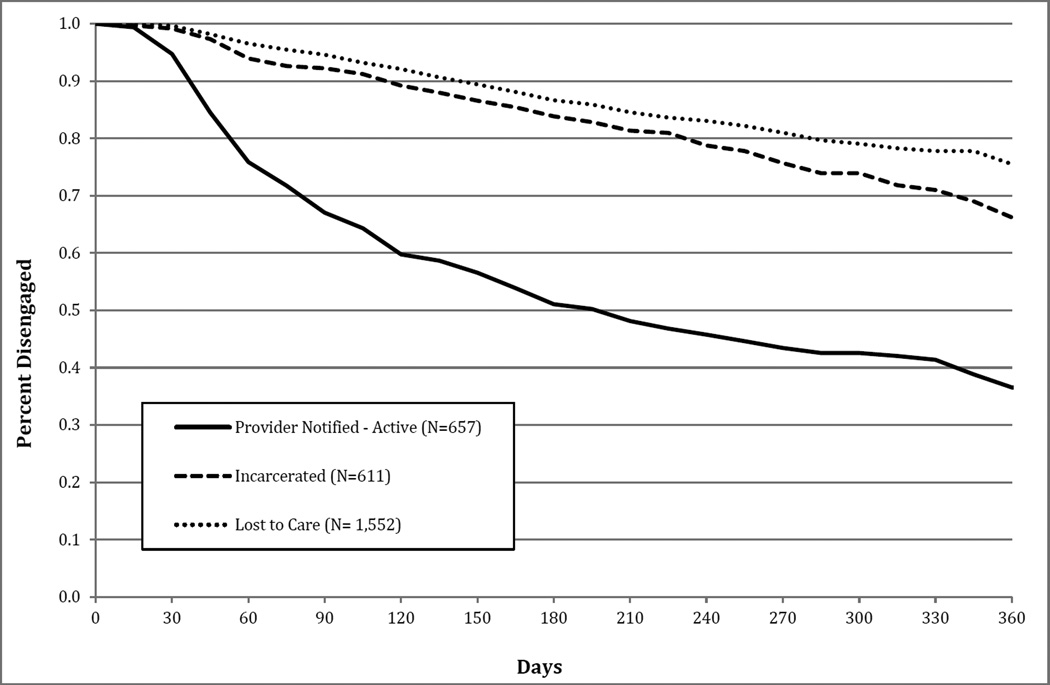

Figure 1 shows time-to-re-engagement for the four groups of individuals. At time zero the provider notified - enhanced group included 14 individuals; the provider notified - active group included 657 individuals; the incarcerated group included 611 individuals; and the lost to care group included 1,552 individuals. No survival curve is shown for the provider notified – enhanced group because of its small size; 10 of the 14 individuals in this group re-engaged by month 3 and 12 re-engaged by month 12. Re-engagement rates at 3 months for the provider notified - active, incarcerated, and lost to care groups were 33%, 8%, and 5%, respectively. By one year, re-engagement rates for these groups were 63%, 34%, and 24%, respectively.

Figure 1.

Rates of re-engagement for groups of individuals who had discontinued services

Discussion

Engagement in services is driven not only by individual characteristics, but (and perhaps more importantly) also by the nature of provider outreach and the quality of the relationship developed between the individual and provider. In the Care Monitoring Initiative, re-engagement rates for individuals confirmed to be disengaged from services varied by both individual characteristics and the nature of provider outreach. The provider notified - enhanced group showed the highest rates of re-engagement, which may be understandable given the small number of individuals and the care monitors’ encouragement of assertive provider outreach due to the perception of potentially imminent risk of danger. The much larger group of individuals in the provider notified - active group showed similar rates of re-engagement in the first 3 months, tapering off throughout the remainder of the follow-up period. We do not have a comparison group to draw conclusions regarding the impact of providers’ outreach efforts and it is possible that these individuals would have re-engaged at a similar rate without outreach.

Individuals in the lost to care group re-engaged at lower rates, which would be expected given the absence of an identified provider able to conduct outreach. The similarly low rates of re-engagement for individuals in the incarcerated group are concerning given that the project care monitors were aware of these individuals’ incarceration status and in a position to recommend post-release referrals and outreach. Such recommendations, if made, did not result in increased rates of engagement. Incarcerated individuals with serious mental illness have complex service needs that are often not adequately addressed (12). These individuals also disengage for policy-related reasons. In NYS Medicaid benefits are not terminated when an individual is incarcerated, but they are suspended and must be re-instated upon release. Individuals may be more likely to disengage if their Medicaid coverage were to remain suspended due to lack of timely notification to the State authority regarding release from incarceration. Clearly, there are many missed opportunities to re-engage these individuals upon re-entry to the community.

Conclusions

The NYC Mental Health Care Monitoring Initiative demonstrated that administrative data could help identify individuals in need of outreach. Subgroups of disengaged populations had different rates of re-engagement and active outreach might have an impact for some of these individuals. Limitations of these data include the inability to distinguish between individual versus provider characteristics that influence re-engagement. We were also unable to determine whether care monitor reviews had an impact on provider engagement efforts and/or re-engagement rates. Finally, we were unable to discern those cases in which the disengagement from treatment represented a rational and appropriate decision made by the individual. Future research and clinical efforts should refine the impact of such care monitoring initiatives and further strengthen public health safety nets.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the New York State Office of Mental Health. The authors thank Dan Cohen for her assistance.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None for any author.

Contributor Information

TE Smith, Columbia University College of Physicians & Surgeons; New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York State Office of Mental Health.

A Appel, New York City Field Office, New York State Office of Mental Health.

SA Donahue, Office of Performance Measurement and Evaluation, State Office of Mental Health, New York, NY.

SM Essock, Columbia University College of Physicians & Surgeons; New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York State Office of Mental Health.

D Thomann-Howe, Harlem United.

A Karpati, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

T Marsik, Bureau of Mental Health, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

RW Myers, New York State Office of Mental Health, Albany, NY, USA.

MJ Sorbero, Community Care Behavioral Health Organization.

BD Stein, RAND Corporation, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

References

- 1.Stein BD, Kogan JN, Sorbero MJ, Thompson W, Hutchinson SL. Predictors of Timely Follow-Up Care Among Medicaid-Enrolled Adults After Psychiatric Hospitalization. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(12):1563–1569. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.12.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olfson M, Marcus SC, Doshi JA. Continuity of care after inpatient discharge of patients with schizophrenia in the Medicaid program: a retrospective longitudinal cohort analysis. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2010;71(7):831–838. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m05969yel. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kreyenbuhl J, Nossel IR, Dixon LB. Disengagement from mental health treatment among individuals with schizophrenia and strategies for facilitating connections to care: a review of the literature. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2009;35:696–703. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Brien A, Fahmy R, Singh SP. Disengagement from mental health services. A literature review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2009;44:558–568. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0476-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Bruce ML, et al. The prevalence and correlates of untreated serious mental illness. Health Services Research. 2001;36:987–1007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lang K, Korn J, Muser E, et al. Predictors of medication nonadherence and hospitalization in Medicaid patients with bipolar I disorder given long-acting or oral antipsychotics. Journal of Medical Economics. 2011;14:217–226. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2011.562265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lang K, Meyers JL, Korn JR, et al. Medication adherence and hospitalization among patients with schizophrenia treated with antipsychotics. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61:1239–1247. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.12.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon LB, Dickerson F, Bellack AS, et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychosocial treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010;36:48–70. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bond GR, Drake RE, Mueser KT, et al. Assertive Community Treatment for people with severe mental illness: critical ingredients and impact on patients. Disease Management and Health Outcomes. 2001;9:141–159. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dieterich M, Irving CB, Park B, et al. Intensive case management for severe mental illness. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007906.pub2. CD007906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith TE, Appel A, Donahue SA, et al. Determining engagement in services for high-need individuals with serious mental illness. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0497-1. published on-line May 1, 2013 (PMID: 23636712) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Constantine R, Andel R, Petrila J, et al. Characteristics and experiences of adults with a serious mental illness who were involved in the criminal justice system. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61:451–457. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.5.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]