Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic, progressive inflammatory arthritis that is common among patients with psoriasis and may result in permanent joint damage and disability. PsA was once considered a relatively benign disease, however research over the past twenty years has significantly changed this notion. We now know that PsA is a systemic inflammatory disorder with health consequences beyond joint function such as cardiovascular disease and similar outcomes to rheumatoid arthritis (RA) including the prevalence of erosions and joint destruction.1, 2 Additionally, we have learned that patients with PsA have highly heterogeneous disease courses.3 Development of more uniformly accepted classification criteria in 2006 have allowed for more comparable populations among epidemiologic studies. In this review, we discuss current knowledge around the epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis including prevalence of disease characteristics, classification of adult and pediatric psoriatic arthritis, the importance of early diagnosis of PsA including methods for screening and knowledge regarding risk factors for the development of PsA. Finally, medical comorbidities associated with PsA will be discussed.

Methods

We performed a systematic review by combining “psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis” with the following MeSH terms: epidemiology, classification, diagnosis, complications, mortality in Ovid Medline. This resulted in 8,936 citations. After limiting to English papers, humans, and 2006 to current, 3515 citations remained. Titles and abstracts were reviewed for these remaining papers. Papers were excluded if they did not refer to psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis (N=288), were case reports (N=644), reviews or editorials (N=383), or focused on basic science or immunology topics (N=210). Finally 7,134 papers were excluded because they focused on skin psoriasis exclusively or were not relevant to the topics of interest. We also included articles prior to 2006 if cited within articles retrieved by the Medline search and if they were considered highly relevant. Abstracts from meeting conferences were not included.

Prevalence and Incidence of PsA in the Population

A number of studies have examined prevalence of PsA in countries all over the world. Prevalence estimates in the United States range from 0.06–0.25% with the lowest estimate derived from a paper that utilized International Classification of Disease ninth edition (ICD-9) codes to identify cases and the highest from articles using patient self-report of diagnosis of PsA.4–6 Prevalence estimates in Europe range from 0.05% in Turkey7 and the Czech Republic 8 to 0.21% in Sweden.9–12 Only a few reports of the prevalence of PsA in South America and Asia exist and suggest that the prevalence is lower in these regions (0.07% in Buenos Aires and 0.02% in China).13, 14 The low prevalence of PsA in China may be due to underdiagnosis as suggested in a study by Yang et al.15 Discrepancies in the prevalence of PsA among these studies is often related to differing definitions of PsA (e.g. use of ICD9 or medical codes versus use of clinical classification criteria). The incidence of PsA in the general population has been examined by relatively few studies. The reported incidence of PsA in recent publications ranges from 3.6–7.2 per 100,000 person years.8, 13, 16, 17 However, publications in 2001–2003 reported a much wider incidence range (0.1–23.1).18

Prevalence and Incidence of PsA Among Patients with Psoriasis

While PsA has a low prevalence in the general population, it is common among patients with psoriasis. Again, prevalence estimates vary considerably (range 6%–41%) depending on the definitions used (i.e. diagnostic codes, rheumatologist diagnosis, classification criteria, diagnostic codes, and the populations measured.11, 14, 15, 19–29 Wilson et al examined the cumulative incidence of PsA over time in patients with psoriasis and reported 1.7%, 3.1% and 5.1% respectively had developed PsA at 5, 10, and 20 years after their diagnosis of psoriasis.17 Eder et al reported an annual incidence of 1.87% in a prospective cohort of 313 patients with psoriasis.30

Alternative Diagnoses, Missed Diagnoses and Misclassification in Studies of Psoriatic Arthritis

Studying the epidemiology of PsA is challenging given the absence of definitive, gold standard diagnostic tests for PsA and the heterogeneous manifestations of the disease. Additionally, patients with psoriasis often have other common reasons for joint pain such as osteoarthritis, gout and fibromyalgia, which can easily be mistaken for PsA.31–35 When using diagnosis codes to define PsA, there is often a concern for misclassification given that patients with psoriasis could have one of these alternate diagnoses. Unfortunately, without examination, this issue is difficult to resolve and this is often a tradeoff for the large sample sizes and rich outcome data afforded by administrative and medical record data. Similarly, studies examining outcomes in patients with PsA compared to psoriasis alone, even within a clinic-based population, may suffer from misclassification of patients with psoriasis and undiagnosed PsA. Studies examining the prevalence of PsA among patients with psoriasis have found that underdiagnosis is common.15, 21, 26 Mease et al found a prevalence of PsA of 30% among patients with psoriasis and among the 285 patients with PsA, 117 (41%) were not previously diagnosed, suggesting a high prevalence of underdiagnosis.26

Defining and Classifying Psoriatic Arthritis

Classification criteria are designed to create more homogenous populations for research.36 Several sets of classification criteria for PsA have been created since the original Moll and Wright criteria in 1973.37 These include the Amor criteria, European Spondylarthropathy Study Group (ESSG) criteria, Vasey and Espinoza criteria, and Classification of Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) criteria.3, 38–43 There is a great deal of variability among the criteria components and test performance of each (sensitivity and specificity). Rheumatologist diagnosis is most commonly used as the reference standard.44, 45 The CASPAR criteria are the most widely used criteria and their high sensitivity and specificity (both 90% or better in most studies but sensitivity as low as 77.3% in D'Angelo et al 2009) have been demonstrated in many settings including dermatology and rheumatology clinics, family practice clinics, and among early arthritis cohorts (despite early suggestions that CASPAR criteria are not ideal for early disease).43, 46–51 Most recently, the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS) developed peripheral and axial spondyloarthropathy criteria. PsA could be classified under either of these criteria depending on whether axial involvement is present (Table 1).52, 53 In a recent study by Van den Berg et al, the peripheral spondyloarthropathy criteria were found to have much lower sensitivity for early PsA compared to CASPAR criteria using the diagnosis from the treating rheumatologist as the gold standard.47 It is unclear what role the new ASAS criteria will play in studies of PsA.54

Table 1.

Commonly used classification criteria for PsA* and new ASAS criteria for peripheral and axial SpA.

| Moll and Wright | CASPAR | Peripheral SpA | Axial SpA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All three of the following: | Inflammatory articular disease (joint, spine or enthesial) with ≥3 points from the following 5 categories: | Arthritis or enthesitis or dactylitis plus either: | Sacroiliitis on imaging plus ≥1 SpA feature | HLA-B27 plus ≥2 SpA feature | |

| 1. Inflammatory arthritis (peripheral arthritis or sacroiliitisor spondylitis) 2. Psoriasis 3. Negative rheumatoid factor (usually) |

1. Current psoriasis (2 pts), personal history of psoriasis or family history of psoriasis (1 Pt) 2. Psoriatic nail dystrophy (onycholysis, pitting or hyperkeratosis) on exam (1 pt) 3. Negative rheumatoid factor (1 pt) 4. Current dactylitis or history of dactylitis recorded by rheumatologist (1 pt) 5. Evidence of juxtaarticular new bone formation (excluding osteophytes) on plain radiographs of the hand or foot (1 pt) |

≥1 SpA feature: Uveitis Psoriasis Crohn's/ulcerative colitis Preceding infection HLA-B27 Sacroiliitis on imaging |

≥2 other SpA features: Arthritis Enthesitis Dactylitis Inflammatory back pain ever Family history of SpA |

SpA features: Inflammatory back pain Arthritis Enthesitis Dactylitis Psoriasis Crohn's/ulcerative colitis Good response to NSAIDs Family history of SpA HLA-B27 Elevated CRP |

|

See Table 1 from Eder L & Gladman DD Curr Rheumatol Rep 2013; 15:316 for comparison of additional classification criteria.

Psoriatic arthritis is a heterogeneous disease

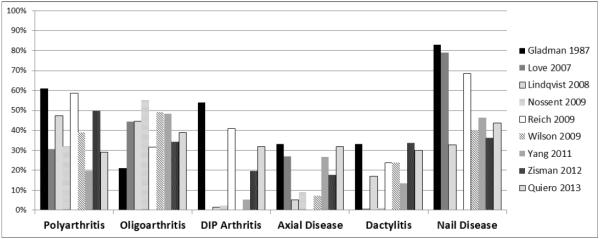

PsA is a clinically heterogeneous disorder. Five subtypes of psoriatic arthritis were initially defined by Moll and Wright: mono- or oligoarthritis, polyarthritis, distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint predominant disease, psoriatic spondylitis and/or sacroiliitis, and arthritis mutilans.37 We now recognize that patients can have any combination of the disease features: peripheral arthritis (mono-, oligo-, or polyarticular with or without DIP involvement), enthesitis, dactylitis, spondylitis and/or sacroiliitis, as well as psoriatic nail disease.3 Peripheral arthritis (either oligoarticular or polyarticular depending on the cohort examined) is the most common disease manifestation. Arthritis mutilans, while one of the original five subtypes of PsA identified by Moll and Wright, is felt to be overall quite rare. However, the prevalence of arthritis mutilans is difficult to determine given the varied definitions.55 As noted, the relative prevalence of the various manifestations varies considerably by site and study (Figure 1).15–17, 23, 29, 56–61 This is particular due to the highly varied definitions of subtypes (e.g. allowing for more than one manifestation or exclusive classification) but also may reflect different subtypes in different populations, the duration of PsA in the population studied, the duration of psoriasis before PsA onset, or age and gender distribution of the population.3, 60, 62 Recognizing the patient's disease features at onset and when selecting therapies may be important to understanding disease and treatment outcomes.63 For example, polyarticular disease has been associated with more erosive disease64 and dactylitis may not respond as well to traditional oral DMARDs.65

Figure 1. Variability of Disease Characteristics by Study.

The prevalence of oligoarthritis, polyarthritis, axial disease, dactylitis and nail disease in a handful of studies is shown above. These manifestations of psoriatic arthritis, the definitions of the manifestations, and the populations included vary considerably by study. For example, Gladman, Lindqvist and Love present data for patients at the first visit whereas Wilson and Reich report data at incident diagnosis. Lindqvist represents a population of patients with early disease (<2 years duration). Axial disease particularly defined quite differently by study. Lindqvist used the original Moll and Wright subgroups to classify patients. Therefore, in that particular study, axial disease as represented here only refers to patients without peripheral arthritis (those patients are classified as oligo- or polyarthritis). In Love et al., axial disease represents patients with inflammatory back pain.

Axial Spondyloarthropathy (AxSpA)

Axial disease or psoriatic spondylitis is present in 7–32% of patients with PsA and may be asymptomatic.15, 23, 59, 66 Among patients with PsA without axial disease at presentation, nail dystrophy, number of radiographically damaged joints, periostitis and elevated ESR increased the risk of developing AxSpA over time.66 Among patients with psoriatic spondylitis, younger age of disease onset was associated with HLAB-27 positivity, family history of SpA, enthesitis, and an isolated axial pattern (without peripheral arthritis). Later onset axial disease was more likely to be associated with polyarthritis and absence of inflammatory back pain. However, despite these differences, the two groups had similar patient reported outcomes including the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index, and Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Radiology Index.67 Recognition of AxSpA is important given differing treatment approaches and prognosis.68, 69

Enthesitis

Enthesitis, present in approximately half of patients, is hypothesized to be the site of disease initiation.70 Enthesitis is generally more often found in the lower extremities with the Achilles and plantar aponeurosis the most commonly involved sites.71 Unfortunately, examination of the entheses is often subjective, there is low interrater realibility even when standardized examination techniques are used, and tenderness on exam is often discordant with findings of inflammation on ultrasound or other imaging techniques.72, 7373, 74 Thus, enthesitis is difficult to follow in studies of therapy effectiveness. The Leeds Enthesitis Index (LEI) is the most commonly used index in studies of PsA but others exist as well (described by Sakkas et al 2013).71, 75 The LEI includes assessment of the lateral epicondyles, proximal Achilles, and medial femoral condyles.75 Ultrasound and MRI examination of the enthesis has improved our understanding of enthesitis and may provide a more objective method to assess and quantify enthesitis.76, 77

Dactylitis

Dactylitis is a common feature in PsA, present in approximately 40% of patients at some point in their disease course, and can occur in either the feet or the hands.65, 71, 78 About half of patients that have dactylitis have it in more than one digit.71 MRI studies suggest that dactylitis is circumferential soft tissue edema in addition to synovitis and tenosynovitis.79 However, in a recent radiographic and histologic evaluation of dactylitis in a child, radiographic features included enhanced signal at digital entheses in the absence of synovitis and tenosynovitis.80 Histologically there was increased vascularity of the tenosynovium and fibromyxoid expansion of fibrous tissue with perivascular lymphocytic inflammation.

Nail Disease

Features of nail psoriasis include pitting, onycholysis, oil spots, linear pitting, and splinter haemorrhages.25, 81–83 Nail psoriasis can be quite painful and result in decreased functional ability and quality of life.84 The prevalence of nail disease among patients with PsA ranges from 41–93%. In fact, most studies have found that nail disease is more common in patients with PsA than patients with psoriasis alone. The prevalence of nail disease in PsO is around 15–50%.23, 81, 83, 85–88 Nail disease (pitting and onycholysis in particular) have been associated with inflammation at the enthesis where the extensor tendon connects to the nail unit89 and is often correlated with DIP joint involvement.90, 91 Furthermore, thickening of the entheses of the extensor tendon on ultrasound was more common in patients with clinical nail changes.92 Nail psoriasis is a risk factor for the development of PsA among patient with PsA, possibly because it is an early sign of enthesial inflammation.17

Imaging features and distinguishing characteristics from RA

Psoriatic arthritis is associated with both bone erosions and new bone formation (i.e. juxta-articular bony proliferation). Erosions occur commonly and often very early in the disease course61, 93 Kane et al found the prevalence of erosions was 27% within the first five months of disease onset and nearly half within two years of disease onset.93 Interestingly, Finzel et al reported the number of erosions were similar among patients with RA and PsA although the shape and location of the erosions were different between the two groups.2 In this study, osteophytes were more commonly seen among patients with PsA than RA. The number of erosions in PsA was correlated with disease duration and the osteophyte count was correlated with age but not disease duration.2 Juxta-articular bony proliferation (not including osteophytes) is among the most specific radiographic features of PsA (as are tuft osteolysis and interphalagenal bony ankylosis).43, 94 However, DIP erosions, periosteoal new bone formation, and diffuse soft tissue swelling also may help distinguish RA from PsA.94 Studies using MRI95, 96 and ultrasound97 examined differences among patients with RA and PsA. Findings from these studies have corroborated the differential locations of erosions between RA and PsA and the increased entheseal disease and periosteal involvement in PsA. Additionally, imaging studies have demonstrated that there is more disease activity present on imaging than noted on physical examination (nearly 75% in one study by Freeston et al) although the clinical significance of this is not well understood.92, 98–100

Psoriatic Arthritis in Children

Psoriasis and PsA are not limited to adults. Juvenile psoriasis has a prevalence of approximately 0.7% increasing from 0.12% at age 1 to 1.2% at age 18.101, 102 Juvenile PsA (JPsA) accounts for approximately 6–8% of all cases of juvenile arthritis;74, 103, 104 Unlike adult PsA, inflammatory arthritis precedes skin psoriasis in about half of children with JPsA.105 This often makes the diagnosis and classification of JPsA quite challenging. Two sets of classification criteria for JPsA exist: the Vancouver criteria for PsA and the International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) criteria (Table 2). The ILAR criteria are the widely used criteria for classifying juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) and include the following categories: oligoarticular, RF positive polyarticular, RF negative polyarticular, systemic, enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA), JPsA, and undifferentiated arthritis.106, 107 As shown in Table 2, the ILAR criteria include a number of restrictions on the diagnosis of JPsA, placing as many as 40% of children who meet Vancouver criteria into the undifferentiated category of JIA (children who meet criteria for more than 1 JIA category). Thus, there is some debate about how to best define JPsA.105, 108 An improved definition for JPsA may be important as long term outcomes are potentially different among patients with JPsA compared to other forms of JIA. Among patients with JPsA, 33% still required DMARDs or bDMARDS after 15 years of follow up compared to 8–13% of patients in other JIA groups.109

Table 2.

Comparison of Vancouver criteria for JPsA and ILAR criteria for JPsA*

| Vancouver | ILAR | |

|---|---|---|

| Inclusion | Arthritis plus psoriasis OR Arthritis plus at least 2 of the following: dactylitis, nail pits, family history of first-or second-degree relative, psoriasis-like rash |

Arthritis plus psoriasis OR Arthritis plus at least two of the following: dactylitis, nail pits or onycholysis, family history of first-degree relative |

| Exclusion | None | Arthritis in HLA-B27 positive male ≥6 years old AS, ERA, sacroilitis with IBD, reactive arthritis, or acute anterior uveitis, OR history of one of these disorders in a first-degree relative. Presence of IgM RF on at least two occasions at least 3 months apart. The presence of systemic JIA Arthritis fulfilling ≥2 JIA categories |

Arthritis must be of unknown etiology, begin before the sixteenth birthday, and persist for at least 6 weeks.

Under the Vancouver criteria, definite JPsA is arthritis plus psoriasis or arthritis plus 3 minor criteria.

Presence of 2 minor criteria is considered probable JPsA.

Abbreviations: JPsA=juvenile psoriatic arthritis; ILAR = International League of Associations for Rheumatology; AS = ankylosing spondylitis; ERA = enthesitis-related arthritis; IBD = inflammatory bowel disease; RF = rheumatoid factor; JIA = juvenile idiopathic arthritis

Adapted from Stoll M, Lio P, Sundel RP and Nigrovic PA. Arthritis Care and Research 2008; 59(10): 51–58; with permission.

Similar to adult PsA, JPsA is a highly heterogeneous disease.110 The prevalence of nail disease and dactylitis (approximately 50% each) is similar to adult PsA and, enthesitis is also common (present in 27% in one study).110 Forty to 88% have an affected first or second degree relative and axial involvement affects 10–40%.109, 111 However, disease manifestations seem to differ by age. Stoll et al described two peaks in onset with the first in toddlers (1–2 years) and the second in early adolescence (age 8–12 years). Younger children (age <5) were more likely to be female and to have dactylitis, small joint involvement and a positive ANA whereas older children were more likely to have persistent oligoarthritis, spondylitis, and enthesitis.102, 110, 112 Development of asymptomatic anterior uveitis is associated with ANA positivity and younger age of disease onset.113 Also similar to adult psoriasis, juvenile psoriasis is associated with an increased prevalence of obesity and comorbidities (including hyperlipidemia, diabetes, hypertension and Crohn's disease).101 This relationship has not been examined specifically in JPsA.

Recognition of Early Psoriatic Arthritis

“Early” PsA is generally considered within the first two years of symptom onset.114 Increasing evidence supports the early diagnosis and treatment of PsA in order to improve long term outcomes.114–117 Gladman et al found patients presenting within 2 years of symptom onset had significantly less disease progression after adjusting for baseline characteristics including start of DMARD therapy at the first visit.115 Treatment outcomes may also be different among patients with early PsA.118 A cohort study within the Swedish Early Psoriatic Arthritis Register found that shorter symptom duration at diagnosis and start of therapy was a predictor of minimal disease activity at 5 years, again suggesting that the earlier disease is identified, the better the outcomes.119 Sorensen et al recently reported an improvement in the delay from symptoms to diagnosis among patients with PsA and RA in Denmark.120 However, underdiagnosis still remains a significant problem.26

Subclinical Disease in Patients with Psoriasis

Given that early initiation of therapy may decrease joint damage and improve long term outcomes, how early should therapy be initiated? It has long been recognized that patients may not report symptoms of joint pain or may not be aware of joint inflammation. Several studies demonstrate that patients with psoriasis often have “subclinical” joint and entheseal inflammation.121, 122 The prevalence of subclinical synovitis and enthesopathy among patients with psoriasis ranges from 3 to 46% and 7 to 33%, respectively. In most studies, the frequency of these findings are significantly higher in patients with psoriasis than in healthy controls.92, 123–128 The meaning of subclinical joint inflammation remains unclear. However, some patients with subclinical inflammation go on to develop symptomatic PsA.129

Improving Detection of Psoriatic Arthritis among Patients with Psoriasis

How can we better identify PsA? Understanding risk factors for PsA among patients with psoriasis could help identify patients with psoriasis who are more likely to develop the disease.130 Additionally, the use of screening tools for PsA in dermatology clinics could facilitate improved recognition of existing disease.

Risk Factors for Psoriatic Arthritis

A handful of studies have examined risk factors for PsA among patients with psoriasis (Box 1). Most of the risk factors identified have not been replicated in additional studies with the exception of obesity, family history of PsA, and injuries or trauma.131, 132 Smoking is generally considered to be a risk factor for psoriasis.133–135 However, studies of smoking as a risk factor for PsA are mixed with one suggesting an inverse association and one suggesting a positive association.134, 136

Screening for Psoriatic Arthritis

Screening for PsA can be as simple as asking about the presence of arthralgias to the use of validated screening tools.146–148 Several groups have developed questionnaires to assist in identification of psoriasis patients with PsA. These questionnaires each have a cut off value which suggests a high likelihood of having inflammatory arthritis, prompting subsequent rheumatology evaluation. 148 Screening tools generally should have high sensitivity149 but given the difficulty with access to rheumatology in many countries, screening for PsA should ideally also have high specificity. Most of the screening tools developed have relatively high sensitivity and specificity in the initial validation studies. However, subsequent studies have noted decreased sensitivity and/or specificity when applied in new populations.24, 150–152 No studies have examined the effectiveness of a screening tool versus usual care in capturing patients with PsA and the overall impact of screening on health care utilization.

Comorbidities in Psoriatic Arthritis

Over the past decade, our understanding of PsA as systemic disease has significantly expanded.164 Approximately 40% of patients with PsA had three or more comorbid conditions and the presence of a comorbidity was associated with decreased quality of life.165 Comorbidities reported to have an increased prevalence or incidence in PsA are reported in Box 2. Longitudinal studies suggesting increased incidence are denoted by the asterisk. The increased risk for metabolic abnormalities including cardiovascular disease and diabetes have been the most striking and of greatest importance to management of patients with PsA.166 While one study has suggested a risk of malignancy similar to RA, population based studies have not suggested an increased risk of cancer, including lymphoma, compared to controls.167–169 Osteoporosis is similarly debated; however, most studies do not suggested an increased prevalence of osteoporosis.170–172 Increased prevalence of diffuse skeletal hyperostosis (DISH)173, monoglonal gammopathy174, and iridocyclitis175 compared to general population statistics have also been reported. Despite the increased prevalence of comorbidities, recent studies have not found an increased risk of mortality among patients with PsA.5, 176–180

Summary

Psoriatic arthritis is a chronic inflammatory arthritis with potentially significant functional disability and poor outcomes including cardiovascular disease. Early detection of psoriatic arthritis is important for improvement in long term outcomes. Use of screening tools and improved knowledge of risk factors could improve early detection.

KEY POINTS.

Psoriatic arthritis is a clinically heterogeneous inflammatory arthritis that is common among patients with psoriasis.

PsA remains under-diagnosed.

Early identification of PsA is important in order to improve long term outcomes.

Knowledge of risk factors for PsA and use of screening tools may improve recognition of PsA among patients with psoriasis.

SYNOPSIS.

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic systemic inflammatory disorder characterized by joint and entheseal inflammation with prevalence 0.05–0.25% of the population and 6–41% of patients with psoriasis. PsA is a highly heterogeneous inflammatory arthritis. In this review, we discuss current knowledge regarding the epidemiology of PsA including disease manifestations, classification criteria for adult and juvenile PsA, methods for recognizing early PsA including use of screening tools and knowledge on risk factors for PsA, and medical comorbidities associated with PsA.

Box 1: Potential Risk Factors for Psoriatic Arthritis.

Nail Dystrophy

Elevated BMI at age 18143

Lifting cumulative loads of >100 pounds/hour138

Severe psoriasis139

Psoriasis location: scalp lesions, intergluteal/perianal lesions17

Corticosteroids in the 2 years prior to psoriasis onset (through PsA onset)144

Rubella vaccinations137

Recurrent oral ulcers137

Moving to a new house137

Infections requiring antibiotics138

Hypercholesterolemia145

Box 2: Comorbidities Associated with PsA.

Table 3.

Available Screening Tools

| Screening Tool | Publication(s) | Description and Caveots | Validation Population | Test Characteristics in Initial Studies | Test Characteristics in Subsequent Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation (PASE) | Husni 2007153 Dominquez 2009154 Ferreyra 2013155 |

Total of 15 questions with score range 15–75. Has been translated into Spanish. Captures disease activity so use of concomitant therapy may change results.156, 157 |

Patients with psoriasis, PsA before therapy, and osteoarthritis. The reference standard was rheumatologist's diagnosis and Moll and Wright Criteria. |

Cut-off 47/75 Sensitivity 82% Specificity 73% |

Haroon 2013: Sensitivity 24% Specificity 94% |

| Cut-off 44/75 Sensitivity 76% Specificity 76% |

Coates 2013: Sensitivity 75% Specificity 39% |

||||

| Spanish Version: Cutoff 34/75 Sensitivity 76% Specificity 74% |

Walsh 2013: Cutoff 44 Sensitivity 76% Specificity 41% |

||||

| Cutoff 47 Sensitivity 63% Specificity 52% |

|||||

|

| |||||

| Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen (ToPAS) | Gladman 2009158 | 12 questions. This questionnaire is unique in its inclusion of photographs of inflamed joints and dactylitis. |

Patients with PsA, psoriasis, general dermatology, general rheumatology and family medicine. The reference standard was a rheumatologist diagnosis of PsA. | Cut-off 8/12 Psoriasis 89.1%, 86.3%; Dermatology 91.9%, 95.2%; Rheumatology 92.6%, 85.7%; Family medicine 90.4%, 100%. |

Mease 2014: Sensitivity 77% Specificity 72% |

| Haroon 2013: Sensitivity 41% Specificity 90% |

|||||

| Coates 2013: Sensitivity 77% Specificity 30% |

|||||

| Walsh 2013: Sensitivity 60% Specificity 55% |

|||||

|

| |||||

| Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) | Ibrahim 2009159 | 5 questions (swollen joints, history of arthritis, heel pain, nail pitting, dactylitis) and a manikin. The manikin does not add to the discriminative ability or scoring but may be helpful to the clinician. | Patients with psoriasis identified by medical codes, mailed questionnaire and 55% of the respondents were examined. The reference standard was a rheumatologist diagnosis. |

Cut-off 3/5. Sensitivity 92% Specificity 78% |

Mease 2014: Sensitivity 84% Specificity 75% |

| Haroon 2013: Sensitivity 28% Specificity 98% |

|||||

| Coates 2013: Sensitivity 77% Specificity 37% |

|||||

| Walsh 2013: Cutoff 44 Sensitivity 69% Specificity 47% |

|||||

|

| |||||

| Electronic Psoriasis and Arthritis Screening Questionnaire (ePASQ) | Khraishi 2011160 | Ten yes or no questions plus two follow up questions with weighted scoring for each and a diagram to mark painful joints which is also weighted. | Patients with suspected early PsA. The reference standard was CASPAR criteria. | Cut-off 7/15 Sensitivity 98% Specificity 75% |

Mease 2014: Sensitivity 67% Specificity 64% |

| Cut-off 8/15 Sensitivity 88% Specificity 75% |

|||||

|

| |||||

| Early Arthritis for Psoriatic Patients (EARP) | Tinazzi 2012161 | Ten items questionnaires with yes or no answers asking about joint and/or tendon pain, swelling and stiffness. | Patients with psoriasis but not systemic therapy. Patients with existing arthritis were excluded. The reference standard was CASPAR criteria applied by a rheumatologist. |

Cut-off 3/10 Sensitivity 85% Specificity 92% |

N/A |

|

| |||||

| CEPPA Screening Tool | Garg 2014162 | 5 questions inquiring about history of joint pain or swelling, morning stiffness, diagnosis of PsA, history of joint xrays, and presence of nail changes. | All adults presenting for psoriasis evaluation within dermatology (with or without PsA). Only patients reporting joint pain were examined. The reference standard was a rheumatologist's diagnosis. | Cut-off 3/5 Sensitivity 86.9% Specificity 71.3% |

N/A |

|

| |||||

| CONTEST and CONTESTjt | Coates 2014163 | Developed from combinations of questions from PASE, PEST, and TO PAS. Validated within Dublin and Utah cohorts using data from Haroon et al and Walsh et al. |

Patients with psoriasis. Patients reaching the previously published cutoff for either PASE, PEST or ToPAS were invited for physical exam. The reference standard was CASPAR criteria. |

CONTEST: Cut-off 4/8 Sensitivity 38–86% Specificity 35–89% |

N/A |

|

CONTESTjw: Cut-off 5/8 Sensitivity 57–89% Specificity 37–71% |

|||||

The sensitivity and specificity used for the subsequent studies was for the cohort of patients with psoriasis but without previous diagnoses of psoriatic arthritis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT The Authors have nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ogdie A, Yu Y, Haynes K, et al. Risk of major cardiovascular events in patients with psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015 Feb;74(2):326–332. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finzel S, Englbrecht M, Engelke K, Stach C, et al. A comparative study of periarticular bone lesions in rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 Jan;70(1):122–127. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.132423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eder L, Gladman DD. Psoriatic arthritis: phenotypic variance and nosology. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2013;15:316. doi: 10.1007/s11926-013-0316-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gelfand JM, Gladman DD, Mease PJ, et al. Epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis in the population of the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(4):573. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shbeeb M, Uramoto KM, Gibson LE, O'Fallon WM, et al. The epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, USA, 1982–1991. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(5):1247–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asgari MM, Wu JJ, Gelfand JM, et al. Validity of diagnostic codes and prevalence of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in a managed care population, 1996–2009. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(8):842–9. doi: 10.1002/pds.3447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cakır N, Pamuk Ö , Derviş E, et al. The prevalences of some rheumatic diseases in western Turkey: Havsa study. Rheumatol Int. 2012 Apr;32(4):895–908. doi: 10.1007/s00296-010-1699-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanova P, Pavelka K, Holcatova I, Pikhart H. Incidence and prevalence of psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and reactive arthritis in the first descriptivepopulation-based study in the Czech Republic. Scand J Rheumatol. 2010 Aug;39(4):310–317. doi: 10.3109/03009740903544212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Löfvendahl S, Theander E, Svensson Å , Carlsson K, et al. Validity of diagnostic codes and prevalence of physician-diagnosed psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in southern Sweden--a population-based register study. PLoS One. 2014 May;9(5):e98024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Love T, Gudbjornsson B, Gudjonsson J, Valdimarsson H. Psoriatic arthritis in Reykjavik, Iceland: prevalence, demographics, and disease course. J Rheumatol. 2007 Oct;34(10):2082–2088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogdie A, Langan S, Love T, et al. Prevalence and treatment patterns of psoriatic arthritis in the UK. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013 Mar;52(3):568–575. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pedersen O, Svendsen A, Ejstrup L, et al. The occurrence of psoriatic arthritis in Denmark. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Oct;67(10):1422–1426. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.082172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soriano E, Rosa J, Velozo E, et al. Incidence and prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in Buenos Aires, Argentina: a 6-year health management organization-based study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011 Apr;50(4):729–734. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li R, Sun J, Ren LM, et al. Epidemiology of eight common rheumatic diseases in China: a large-scale cross-sectional survey in Beijing. Rheumatology. 2012;51(4):721–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Q, Qu L, Tian H, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of psoriatic arthritis in Chinese patients with psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011 Dec;25(12):1409–1414. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.03985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nossent J, Gran J. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of psoriatic arthritis in northern Norway. Scand J Rheumatol. 2009;38(4):251–255. doi: 10.1080/03009740802609558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson F, Icen M, Crowson C, et al. Incidence and clinical predictors of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Feb;61(2):233–239. doi: 10.1002/art.24172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alamanos Y, Voulgari P, Drosos A. Incidence and prevalence of psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review. J Rheumatol. 2008 Jul;35(7):1354–1358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carneiro JN, Paula AP, Martins GA. Psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: evaluation of clinical and epidemiological features in 133 patients followed at the University Hospital of Brasilia. Anais Brasileiros de Derm. 2012;87(4):539–44. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962012000400003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henes JC, Ziupa E, Eisfelder M, et al. High prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in dermatological patients with psoriasis: a cross-sectional study. Rheumatol Int. 2014;34(2):227–34. doi: 10.1007/s00296-013-2876-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ibrahim G, Waxman R, Helliwell P. The prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in people with psoriasis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Oct;61(10):1373–1378. doi: 10.1002/art.24608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jamshidi F, Bouzari N, Seirafi H, et al. The prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in psoriatic patients in Tehran, Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2008;11(2):162–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Love T, Gudbjornsson B, Gudjonsson J, Valdimarsson H. Psoriatic arthritis in Reykjavik, Iceland: prevalence, demographics, and disease course. J Rheumatol. 2007 Oct;34(10):2082–2088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haroon M, Kirby B, FitzGerald O. High prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with severe psoriasis with suboptimal performance of screening questionnaires. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 May;72(5):736–740. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Love T, Gudjonsson J, Valdimarsson H, Gudbjornsson B. Psoriatic arthritis and onycholysis -- results from the cross-sectional Reykjavik psoriatic arthritis study. J Rheumatol. 2012 Jul;39(7):1441–1444. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.111298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mease P, Gladman D, Papp K, et al. Prevalence of rheumatologist-diagnosed psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis in European/North American dermatology clinics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Nov;69(5):729–735. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khraishi M, Chouela E, Bejar M, et al. High prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in a cohort of patients with psoriasis seen in a dermatology practice. J Cutan Med Surg. 2012;16(2):122–7. doi: 10.2310/7750.2011.10101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radtke M, Reich K, Blome C, Rustenbach S, et al. Prevalence and clinical features of psoriatic arthritis and joint complaints in 2009 patients with psoriasis: results of a German national survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009 Jun;23(6):683–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reich K, Krüger K, Mössner R, Augustin M. Epidemiology and clinical pattern of psoriatic arthritis in Germany: a prospective interdisciplinary epidemiological study of 1511 patients with plaque-type psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2009 May;160(5):1040–1047. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.09023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eder L, Chandran V, Shen H, et al. Incidence of arthritis in a prospective cohort of psoriasis patients. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011 Apr;63(4):619–622. doi: 10.1002/acr.20401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merola J, Wu S, Han J, et al. Psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and risk of gout in US men and women. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205212. Epub ahead. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mody E, Husni ME, Schur P, Qureshi AA. Multidisciplinary evaluation of patients with psoriasis presenting with musculoskeletal pain: a dermatology: rheumatology clinic experience. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(5):1050–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marchesoni A, Atzeni F, Spadaro A, et al. Identification of the clinical features distinguishing psoriatic arthritis and fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2012 Apr;39(4):849–855. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Marco G, Cattaneo A, Battafarano N, et al. Not simply a matter of psoriatic arthritis: epidemiology of rheumatic diseases in psoriatic patients. Arch Dermatol Res. 2012 Nov;304(9):719–726. doi: 10.1007/s00403-012-1281-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan A, Grainger A, Tanner S, et al. A high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging study of distal interphalangeal joint arthropathy in psoriatic arthritis and osteoarthritis: are they the same? Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Apr;54(4):1328–1333. doi: 10.1002/art.21736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aggarwal R, Ringold S, Khanna D, et al. Distinctions between diagnostic and classification criteria? Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015 Mar; doi: 10.1002/acr.22583. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1002/acr.22583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moll JM, Wright V. Psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1973;3(1):55–78. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(73)90035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amor B, Dougados M, Mijiyawa M. Criteria of the classification of spondylarthropathies. Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic. 1990 Feb;57(2):85–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dougados M, van der Linden S, Juhlin R, et al. The European Spondylarthropathy Study Group preliminary criteria for the classification of spondylarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34(10):1218–27. doi: 10.1002/art.1780341003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bennett RM. Psoriatic arthritis. In: McCarty DJ, editor. Arthritis and allied conditions. 9 ed Lea; Philadelphia: Feb, 1979. p. 645. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fournie B, Crognier L, Arnaud C, et al. Proposed classification criteria of psoriatic arthritis: a preliminary study in 260 patients. Rev Rhum Engl Ed. 1999;66(10):446–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vasey F, Espinoza LR. Psoriatic arthropathy. In: Calin A, editor. Spondyloarthropathies. Grune & Stratton; Orlando: 1984. pp. 151–85. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor W, Helliwell P. Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis: Development of New Criteria From a Large International Study [PsA - CASPAR] Arth Rheum. 2006;54:2665–2673. doi: 10.1002/art.21972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Congi L, Roussou E. Clinical application of the CASPAR criteria for psoriatic arthritis compared to other existing criteria. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010 May;28(3):304–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gunal EK, Kamali S, Gul A, et al. Clinical evaluation and comparison of different criteria for classification in Turkish patients with psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2008;28(10):959–64. doi: 10.1007/s00296-008-0553-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.D'Angelo S, Mennillo G, Cutro M, et al. Sensitivity of the classification of psoriatic arthritis criteria in early psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2009 Feb;36(2):368–370. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van den Berg R, van Gaalen F, van der Helm-van Mil A, et al. Performance of classification criteria for peripheral spondyloarthritis and psoriatic arthritis in the Leiden Early Arthritis cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 Aug;71(8):1366–1369. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chandran V, Schentag C, Gladman D. Sensitivity and specificity of the CASPAR criteria for psoriatic arthritis in a family medicine clinic setting. J Rheumatol. 2008 Oct;35(10):2069–2070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chandran V, Schentag C, Gladman D. Sensitivity of the classification of psoriatic arthritis criteria in early psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007 Dec;57(8):1560–1563. doi: 10.1002/art.23104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coates L, Conaghan P, Emery P, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the classification of psoriatic arthritis criteria in early psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012 Oct;64(10):3150–3155. doi: 10.1002/art.34536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lueng YY, Tam LS, Ho KW, et al. Evaluation of the CASPAR criteria for psoriatic arthritis in the Chinese population. Rheumatology. 2010;49(1):112–5. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society classification criteria for peripheral spondyloarthritis and for spondyloarthritis in general. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 Jan;70(1):25–31. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.133645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axialspondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009 Jun;68(6):777–783. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.108233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taylor WJ, Robinson PC. Classification criteria: peripheral spondyloarthropathy and psoriatic arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2013;15(4):317. doi: 10.1007/s11926-013-0317-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haddad A, Chandran V. Arthritis mutilans. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2013;15(4):321. doi: 10.1007/s11926-013-0321-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gladman DD, Shuckett R, Russell ML, et al. Psoriatic arthritis (PSA)—an analysis of 220 patients. Q J Med. 1987;62(238):127–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Madland T, Apalset E, Johannessen A, et al. Prevalence, disease manifestations, and treatment of psoriatic arthritis in Western Norway [PsA Epi] J Rheumatol. 2005;32(10):1918–1922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lindqvist U, Alenius G, Husmark T, et al. The Swedish early psoriatic arthritis register-- 2-year followup: a comparison with early rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2008 Apr;35(4):668–673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Soy M, Karaca N, Umit E, et al. Joint and nail involvement in Turkish patients with psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2008 Dec;29(2):223–225. doi: 10.1007/s00296-008-0686-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Queiro R, Tejón P, Coto P, et al. Clinical differences between men and women with psoriatic arthritis: relevance of the analysis of genes andpolymorphisms in the major histocompatibility complex region and of the age at onset of psoriasis. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/482691. Epub 2013 Apr 16. doi: 10.1155/2013/482691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zisman D, Eder L, Elias M, et al. Clinical and demographic characteristics of patients with psoriatic arthritis in northern Israel. Rheumatol Int. 2012 Mar;32(3):595–600. doi: 10.1007/s00296-010-1673-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Queiro R, Alperi M, Alonso-Castro S, et al. Patients with psoriatic arthritis may show differences in their clinical and genetic profiles depending on their age at psoriasis onset. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012 Jul-Aug;30(4):476–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tillett W, McHugh N. Treatment algorithms for early psoriatic arthritis: do they depend on disease phenotypes? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2012;14(4):334–42. doi: 10.1007/s11926-012-0265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Queiro-Silva R, Torre-Alonso JC, Tinture-Equren T, Lopez-Lagunas I. A polyarticular onset predicts erosive and deforming disease in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(1):68–70. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gladman D, Ziouzina O, Thavaneswaran A, Chandran V. Dactylitis in psoriatic arthritis: prevalence and response to therapy in the biologic era. J Rheumatol. 2013 Aug;40(8):1357–1359. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chandran V, Tolusso D, Cook R, Gladman D. Risk factors for axial inflammatory arthritis in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2010 Apr;37(4):809–815. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.091059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Queiro R, Alperi M, Lopez A, et al. Clinical expression, but not disease outcome, may vary according to age at disease onset in psoriatic spondylitis. Joint Bone Spine. 2008;75(5):544–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thavaneswaran A, Chandran V, Gladman D. Do Patients with Psoriatic Arthritis Fall Into Distinct Clinical Sub- Groups—a Cluster Analysis? Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(Suppl):S1106. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ritchlin C, Kavanaugh A, Gladman DD, et al. Treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1387–1394. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.094946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McGonagle D, Helliwell P, Veale D. Enthesitis in psoriatic disease. Dermatology. 2012;225(2):100–109. doi: 10.1159/000341536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sakkas L, Alexiou I, Simopoulou T, Vlychou M. Enthesitis in psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Dec;43(3):325–334. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weiss PF, Chauvin NA, Klink AJ, et al. Detection of enthesitis in children with enthesitis-related arthritis: dolorimetry compared to ultrasonography. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(1):218–27. doi: 10.1002/art.38197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.D'Agostino MA, Said-Nahal R, Hacquard-Bouder C, et al. Assessment of peripheral enthesitis in the spondylarthropathies by ultrasonography combined with power Doppler: a cross-sectional study. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(2):523–33. doi: 10.1002/art.10812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Weiss P, Beukelman T, Schanberg L, et al. Enthesitis-related arthritis is associated with higher pain intensity and poorer health status in comparison with other categories of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance Registry. J Rheumatol. 2012 Dec;39(12):2341–2351. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.120642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Healy P, Helliwell P. Measuring clinical enthesitis in psoriatic arthritis: assessment of existing measures and development of an instrument specific to psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 May;59(5):686–691. doi: 10.1002/art.23568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kaeley G. Review of the use of ultrasound for the diagnosis and monitoring of enthesitis in psoriatic arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2011 Aug;13(4):338–345. doi: 10.1007/s11926-011-0184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Coates L, Hodgson R, Conaghan P, Freeston J. MRI and ultrasonography for diagnosis and monitoring of psoriatic arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012 Dec;26(6):805–822. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Payet J, Gossec L, Paternotte S, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of dactylitis in spondylarthritis: a descriptive analysis of 275 patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30(2):191–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Healy P, Groves C, Chandramohan M, Helliwell P. MRI changes in psoriatic dactylitis--extent of pathology, relationship to tenderness and correlation with clinical indices. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008 Jan;47(1):92–95. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tuttle KS, Vargas SO, Callahan MJ, et al. Enthesitis as a component of dactylitis in psoriatic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: histology of an established clinical entity. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2015;13:7. doi: 10.1186/s12969-015-0003-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kyriakou A, Patsatsi A, Sotiriadis D. Detailed analysis of specific nail psoriasis features and their correlations with clinical parameters: a cross-sectional study. Dermatology. 2011;223(3):222–229. doi: 10.1159/000332974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Palmou N, Marzo-Ortega H, Ash Z, et al. Linear pitting and splinter haemorrhages are more commonly seen in the nails of patients with established psoriasis in comparison to psoriatic arthritis. Dermatology. 2011;223(4):370–373. doi: 10.1159/000335571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Love T, Gudjonsson J, Valdimarsson H, Gudbjornsson B. Small joint involvement in psoriatic arthritis is associated with onycholysis: the Reykjavik Psoriatic Arthritis Study. Scand J Rheumatol. 2010 Aug;39(4):299–302. doi: 10.3109/03009741003604559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Baran R. The burden of nail psoriasis: an introduction. Dermatology. 2010;221(Suppl 1):1–5. doi: 10.1159/000316169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jiaravuthisan M, Sasseville D, Vender R, et al. Psoriasis of the nail: anatomy, pathology, clinical presentation, and a review of the literature on therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007 Jul;57(1):1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.07.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ash Z, Tinazzi I, Gallego C, et al. Psoriasis patients with nail disease have a greater magnitude of underlying systemic subclinical enthesopathy than those with normal nails. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 Apr;71(4):553–556. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Augustin M, Reich K, Blome C, et al. Nail psoriasis in Germany: epidemiology and burden of disease. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(3):580–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Prasad PV, Bikku B, Kaviarasan PK, Senthilnathan A. A clinical study of psoriatic arthropathy. Indian J Derm Ven. 2007;73(3):166–70. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.32739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.McGonagle D, Palmou Fontana N, Tan A, Benjamin M. Nailing down the genetic and immunological basis for psoriatic disease. Dermatology. 2010;221(Suppl 1):15–22. doi: 10.1159/000316171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Scarpa R, Cuocolo A, Peluso R, et al. Early psoriatic arthritis: the clinical spectrum [subclinical psa imaging] J Rheumatol. 2008;35(1):137–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dalbeth N, Pui K, Lobo M, et al. Nail disease in psoriatic arthritis: distal phalangeal bone edema detected by magnetic resonance imaging predicts development of onycholysis and hyperkeratosis. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(4):841–3. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.111118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Aydin S, Castillo-Gallego C, Ash Z, et al. Ultrasonographic assessment of nail in psoriatic disease shows a link between onychopathy and distal interphalangeal joint extensor tendon enthesopathy. Dermatology. 2012;225(3):231–235. doi: 10.1159/000343607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kane D, Stafford L, Bresnihan B, FitzGerald O. A prospective, clinical and radiological study of early psoriatic arthritis: an early synovitis clinic experience. [early PsA] Rheumatology. 2003;42(12):1460–1468. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ichikawa N, Taniguchi A, Kobayashi S, Yamanaka H. Performance of hands and feet radiographs in differentiation of psoriatic arthritis from rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2012 Oct;15(5):462–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2012.01818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Narváez J, Narváez JA, de Albert M, et al. Can magnetic resonance imaging of the hand and wrist differentiate between rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis in the early stages of the disease? Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;42(3):234–45. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tehranzadeh J, Ashikyan O, Anavim A, Shin J. Detailed analysis of contrast-enhanced MRI of hands and wrists in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37(5):433–42. doi: 10.1007/s00256-008-0451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fournié B, Margarit-Coll N, Champetier de Ribes TL, et al. Extrasynovial ultrasound abnormalities in the psoriatic finger. Joint Bone Spine. 2006;73(5):527–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2006.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Aydin S, Ash Z, Tinazzi I, et al. The link between enthesitis and arthritis in psoriatic arthritis: a switch to a vascular phenotype at insertions may play a role in arthritis development. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Jun;72(6):992–995. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Freeston J, Coates L, Nam J, et al. Is there subclinical synovitis in early psoriatic arthritis?. A clinical comparison with gray-scale and power Doppler ultrasound. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014 Mar;66(3):432–439. doi: 10.1002/acr.22158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Weckbach S, Schewe S, Michaely HJ, et al. Whole-body MR imaging in psoriatic arthritis: additional value for therapeutic decision making. Eur J Radiol. 2011;77(1):149–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Augustin M, Glaeske G, Radtke M, et al. Epidemiology and comorbidity of psoriasis in children. Br J Dermatol. 2010 Mar;162(3):633–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Stoll M, Zurakowski D, Nigrovic L, et al. Patients with juvenile psoriatic arthritis comprise two distinct populations. Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Nov;54(11):3564–3572. doi: 10.1002/art.22173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Berard R, Tomlinson G, Li X, et al. Description of active joint count trajectories in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2014 Dec;41(12):2466–2473. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Guzman J, Oen K, Tucker L, et al. The outcomes of juvenile idiopathic arthritis in children managed with contemporary treatments: results from the ReACCh-Out cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 May; doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205372. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nigrovic P. Juvenile psoriatic arthritis: bathwater or baby? J Rheumatol. 2009 Sep;36(9):1861–1863. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Stoll M, Lio P, Sundel R, Nigrovic P. Comparison of Vancouver and International League of Associations for rheumatology classification criteria for juvenile psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Jan;59(1):51–58. doi: 10.1002/art.23240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Petty R, Southwood T, Manners P, et al. International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol. 2004 Feb;31(2):390–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Demirkaya E, Ozen S, Bilginer Y, et al. The distribution of juvenile idiopathic arthritis in the eastern Mediterranean: results from the registry of the Turkish Paediatric Rheumatology Association. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011 Jan-Feb;29(1):111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Flatø B, Lien G, Smerdel-Ramoya A, Vinje O. Juvenile psoriatic arthritis: long term outcome and differentiation from other subtypes of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2009 Mar;36(3):642–650. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Stoll M, Punaro M. Psoriatic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a tale of two subgroups. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011 Sep;23(5):437–443. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328348b278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Häfner R, Michels H. Psoriatic arthritis in children. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1996 Sep;8(5):467–472. doi: 10.1097/00002281-199609000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Stoll M, Nigrovic P. Subpopulations within juvenile psoriatic arthritis: a review of the literature. Clin Dev Immunol. 2006 Jun-Dec;13(2–4):377–380. doi: 10.1080/17402520600877802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Calandra S, Gallo M, Consolaro A, et al. Female sex and oligoarthritis category are not risk factors for uveitis in Italian children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2014 Jul;41(7):1416–1425. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.131494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gladman D. Early psoriatic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2012 May;38(2):373–386. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gladman D, Thavaneswaran A, Chandran V, Cook R. Do patients with psoriatic arthritis who present early fare better than those presenting later in the disease? Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 Dec;70(12):2152–2154. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.150938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tillett W, Jadon D, Shaddick G, et al. Smoking and delay to diagnosis are associated with poorer functional outcome in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Aug;72(8):1358–1361. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Haroon M, Gallagher P, Fitzgerald O. Diagnostic delay of more than 6 months contributes to poor radiographic and functional outcome in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204858. Epub Ahead. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kirkham B, de Vlam K, Li W, et al. Early treatment of psoriatic arthritis is associated with improved patient-reported outcomes: findings from the etanercept PRESTA trial. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33(1):11–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Theander E, Husmark T, Alenius G, et al. Early psoriatic arthritis: short symptom duration, male gender and preserved physical functioning at presentation predict favourable outcome at 5-year follow-up. Results from the Swedish Early Psoriatic Arthritis Register(SwePsA) Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 Feb;73(2):407–413. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sørensen J, Hetland M, departments of rheumatology in Denmark Diagnostic delay in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis: results from the Danish nationwide DANBIO registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015 Mar;74(3):e12. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Palazzi C, Lubrano E, D'Angelo S, Olivieri I. Beyond early diagnosis: occult psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2010 Aug;37(8):1556–1558. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.091026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.McGonagle D, Ash Z, Dickie L, et al. The early phase of psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 Mar;70(Suppl 1):i71–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.144097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Naredo E, Möller I, de Miguel E, et al. High prevalence of ultrasonographic synovitis and enthesopathy in patients with psoriasis without psoriatic arthritis: a prospective case-control study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011 Oct;50(10):1838–1848. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Emad Y, Ragab Y, Bassyouni I, et al. Enthesitis and related changes in the knees in seronegative spondyloarthropathies and skin psoriasis: magnetic resonance imaging case-control study. J Rheumatol. 2010 Aug;37(8):1709–1717. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Erdem C, Tekin N, Sarikaya S, et al. MR imaging features of foot involvement in patients with psoriasis. Eur J Radiol. 2008 Sep;67(3):521–525. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Gisondi P, Tinazzi I, El-Dalati G, et al. Lower limb enthesopathy in patients with psoriasis without clinical signs of arthropathy: a hospital-based case-control study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Jan;67(1):26–30. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.075101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Raza N, Hameed A, Ali M. Detection of subclinical joint involvement in psoriasis with bone scintigraphy and its response to oral methotrexate. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008 Jan;33(1):70–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2007.02581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Offidani A, Cellini A, Valeri G, Giovagnoni A. Subclinical joint involvement in psoriasis: magnetic resonance imaging and X-ray findings. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998 Nov;78(6):463–465. doi: 10.1080/000155598442809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Tinazzi I, McGonagle D, Domenico B, et al. Preliminary Evidence That Subclinical Enthesopathy May Predict Psoriatic Arthritis in Patients with Psoriasis [Subclinical psa] J Rheumatol. 2011;38:2691–2692. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ogdie A, Gelfand J. Identification of Risk Factors for Psoriatic Arthritis [Risk factors] Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(7):785. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Hsieh J, Kadavath S, Efthimiou P. Can traumatic injury trigger psoriatic arthritis?. A review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2014 May;33(5):601–608. doi: 10.1007/s10067-013-2436-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Olivieri I, Padula A, D'Angelo S, Scarpa R. Role of trauma in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(11):2085–7. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ozden MG, Tekin NS, Gürer MA, et al. Environmental risk factors in pediatric psoriasis: a multicenter case-control study. Pediatr Derm. 2011;28(3):306–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Li W, Han J, Qureshi A. Smoking and risk of incident psoriatic arthritis in US women. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 Jun;71(6):804–808. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Huerta C, Rivero E, Rodríguez LA. Incidence and risk factors for psoriasis in the general population. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(12):1559–65. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.12.1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Eder L, Shanmugarajah S, Thavaneswaran A, et al. The association between smoking and the development of psoriatic arthritis among psoriasis patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 Feb;71(2):219–224. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.147793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Pattison E, Harrison B, Griffiths C, et al. Environmental risk factors for the development of psoriatic arthritis: results from a case-control study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 May;67(5):627–626. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.073932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Eder L, Law T, Chandran V, et al. Association between environmental factors and onset of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011 Aug;63(8):1091–1097. doi: 10.1002/acr.20496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Tey H, Ee H, Tan A, et al. Risk factors associated with having psoriatic arthritis in patients with cutaneous psoriasis. J Dermatol. 2010 May;37(5):426–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Ciurtin C, Roussou E. Cross-sectional study assessing family members of psoriatic arthritis patients affected by the same disease: differences between Caucasian, South Asian and Afro-Caribbean populations living in the same geographic region. Int J Rheum Dis. 2013;16(4):418–24. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Li W, Han J, Qureshi A. Obesity and risk of incident psoriatic arthritis in US women. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 Aug;71(8):1267–1772. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Love T, Zhu Y, Zhang Y, et al. Obesity and the risk of psoriatic arthritis: a population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 Aug;71(8):1273–1277. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Soltani-Arabshahi R, Wong B, Feng B, et al. Obesity in early adulthood as a risk factor for psoriatic arthritis. Arch Dermatol. 2010 Jul;146(7):721–726. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Thumboo J, Uramoto K, Shbeeb M, et al. Risk factors for the development of psoriatic arthritis: a population based nested case control study. J Rheumatol. 2002 Apr;29(4):757–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Wu S, Li WQ, Han J, et al. Hypercholesterolemia and risk of incident psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in US women. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(2):304–10. doi: 10.1002/art.38227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Taylor SL, Petrie M, O'Rourke KS, Feldman SR. Rheumatologists' recommendations on what to do in the dermatology office to evaluate and manage psoriasis patients' joint symptoms. J Dermatolog Treat. 2009;20(6):350–3. doi: 10.3109/09546630902817887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Dominguez P, Gladman DD, Helliwell P, et al. Development of screening tools to identify psoriatic arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2010;12(4):295–9. doi: 10.1007/s11926-010-0113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Haddad A, Chandran V. How can psoriatic arthritis be diagnosed early? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2012 Aug;14(4):358–363. doi: 10.1007/s11926-012-0262-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Fletcher RH, Fletcher SW. Clinical Epidemiology: The Essentials. 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 150.Coates L, Aslam T, Al Balushi F, et al. Comparison of three screening tools to detect psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis (CONTEST study) Br J Dermatol. 2013 Apr;168(4):802–807. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Walsh J, Callis Duffin K, Krueger G, Clegg D. Limitations in screening instruments for psoriatic arthritis: a comparison of instruments in patients with psoriasis. J Rheumatol. 2013 Mar;40(3):287–93. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.120836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Mease P, Gladman D, Helliwell P, et al. Comparative performance of psoriatic arthritis screening tools in patients with psoriasis in European/NorthAmerican dermatology clinics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Oct;71(4):649–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Husni M, Meyer K, Cohen D, et al. The PASE questionnaire: pilot-testing a psoriatic arthritis screening and evaluation tool. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007 Oct;57(4):581–587. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Dominguez P, Husni M, Holt E, et al. Validity, reliability, and sensitivity-to-change properties of the psoriatic arthritis screening and evaluation questionnaire. Arch Dermatol Res. 2009 Sep;301(8):573–579. doi: 10.1007/s00403-009-0981-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Ferreyra Garrott L, Soriano E, Rosa J, et al. Validation in Spanish of a screening questionnaire for the detection of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013 Mar;52(3):510–514. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Husni M, Qureshi A, Koenig A, et al. Utility of the PASE questionnaire, psoriatic arthritis (PsA) prevalence and PsA improvement with anti-TNF therapy: results from the PRISTINE trial. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014 Feb;25(1):90–95. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2013.800185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Merola J, Husni M, Qureshi A. Screening instruments for psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2013 Sep;40(9):1623. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Gladman D, Schentag C, Tom B, et al. Development and initial validation of a screening questionnaire for psoriatic arthritis: the Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen (ToPAS) Ann Rheum Dis. 2009 Apr;68(4):497–501. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.089441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Ibrahim G, Buch M, Lawson C, et al. Evaluation of an existing screening tool for psoriatic arthritis in people with psoriasis and the development of a new instrument: the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) questionnaire. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009 May-Jun;27(3):469–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Khraishi M, Mong J, Mugford G, Landells I. The electronic Psoriasis and Arthritis Screening Questionnaire (ePASQ): a sensitive and specific tool to diagnose psoriatic arthritis patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 2011 May-Jun;15(3):143–149. doi: 10.2310/7750.2011.10018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Tinazzi I, Adami S, Zanolin E, et al. The early psoriatic arthritis screening questionnaire: a simple and fast method for the identification of arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012 Nov;51(11):2058–2063. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Garg N, Truong B, Ku J, et al. A novel, short, and simple screening questionnaire can suggest presence of psoriatic arthritis in psoriasis patients in a dermatology clinic. Clin Rheumatol. 2014 May; doi: 10.1007/s10067-014-2658-3. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Coates L, Walsh J, Haroon M, et al. Development and testing of new candidate psoriatic arthritis screening questionnaires combining optimal questions from existing tools. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014 Sep;66(9):1410–1416. doi: 10.1002/acr.22284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Ogdie A, Schwartzman S, Husni M. Recognizing and managing comorbidities in psoriatic arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2015 Mar;27(2):118–126. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Husted J, Thavaneswaran A, Chandran V, Gladman D. Incremental effects of comorbidity on quality of life in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2013 Aug;40(8):1349–1356. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.121500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Jamnitski A, Symmons D, Peters MJL, et al. Cardiovascular comorbidities in patients with psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(2):211–6. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Gross R, Schwartzman-Morris J, Krathen M, et al. American College of Rheumatology Meeting. 2011. The risk of malignancy in a large cohort of patients with psoriatic arthritis. [Google Scholar]

- 168.Hellgren K, Smedby K, Backlin E, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and risk of malignant lymphoma: a cohort study based on nationwide prospectively recorded data from Sweden. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(5):1282–90. doi: 10.1002/art.38339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Rohekar S, Tom B, Hassa A, et al. Prevalence of malignancy in psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Jan;58(1):82–87. doi: 10.1002/art.23185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Pedreira P, Pinheiro M, Szejnfeld V. Bone mineral density and body composition in postmenopausal women with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis ResTher. 2011 Feb;13(1):R16. doi: 10.1186/ar3240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Grazio S, Cvijetić S, Vlak T, et al. Osteoporosis in psoriatic arthritis: is there any? Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2011 Dec;123(23–24):743–750. doi: 10.1007/s00508-011-0095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Del Puente A, Esposito A, Parisi A, et al. Osteoporosis and psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2012 Jul;89:36–38. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.120240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Haddad A, Thavaneswaran A, Toloza S, et al. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2013 Aug;40(8):1367–1773. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.121433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Eder L, Thavaneswaran A, Pereira D, et al. Prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy among patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2012 May;39(3):564–567. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.111054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Niccoli L, Nannini C, Cassarà E, et al. Frequency of iridocyclitis in patients with early psoriatic arthritis: a prospective, follow up study. Int J Rheum Dis. 2012 Aug;15(4):414–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2012.01736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Ogdie A, Haynes K, Troxel A, et al. Mortality in Patients with Psoriatic Arthritis Compared to Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis, Psoriasis Alone, and the General Population. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):149–53. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Arumugam R, McHugh N. Mortality and causes of death in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2012 Jul;89:32–5. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.120239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Buckley C, Cavill C, Taylor G, et al. Mortality in psoriatic arthritis - a single-center study from the UK. J Rheumatol. 2010 Oct;37(10):2141–2144. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Wong K, Gladman DD, Husted J, et al. Mortality studies in psoriatic arthritis: results from a single outpatient clinic; causes and risk of death. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(10):1868–72. doi: 10.1002/art.1780401021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Ali Y, Tom BDM, Schentag CT, et al. Improved survival in psoriatic arthritis with calendar time. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(8):2708–14. doi: 10.1002/art.22800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Han C, Robinson DW, Hackett MV, et al. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2167–2172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Gladman DD, Ang M, Su L, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1131–1135. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.094839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]