Abstract

Background

BRAF V600E mutation has been identified in up to 2/3 of pleomorphic xanthoastrocytomas (PXA), WHO grade II, as well as varying percentages of pleomorphic xanthoastrocytomas with anaplastic features (PXA-A), gangliogliomas, extra-cerebellar pilocytic astrocytomas, and rarely, giant cell GBMs (GC-GBMs). GC-GBMs and epithelioid GBMs (E-GBMs) can be histologically challenging to distinguish from PXA-A. We undertook this study specifically to address whether these 2 tumor types also showed the mutation.

Design

We tested our originally-reported cohort of 8 E-GBMs and 2 rhabdoid GBMs (Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:341–354) as well as 5 new E-GBMs (1 pediatric, 4 adult) and 9 GC-GBMs (2 pediatric, 7 adult) (n=24) for BRAF V600E mutational status. 21/24 had sufficient material for IDH1 immunostaining, which is usually absent in PXAs, PXA-As, and primary GBMs, but present in secondary GBMs.

Results

Patients ranged in age from 4–67 years. BRAF V600E mutation was identified in 7/13 of E-GBMs, including 3 of our original cases; patients with mutation were ages 1050 years. None of the 9 GC-GBMs or 2 rhabdoid GBMs manifested this mutation, including pediatric patients. The sole secondary E-GBM was the single case manifesting positive IDH1 immunoreactivity.

Conclusion

A high percentage of E-GBMs manifest BRAF V600E mutation, paralleling PXAs. All rhabdoid GBMs and GC-GBMs were negative, although larger multi-institutional cohorts will have to be tested to extend this result. BRAF V600E mutational analyses should be performed on E-GBMs, particularly in all pediatric and young-aged adults, given the potential for BRAF inhibitor therapy in this subset of GBM patients.

Keywords: giant cell GBM, epithelioid GBM, pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, BRAF, IDH1, ganglioglioma

INTRODUCTION

Mutation in BRAF V600E at position 600, specifically V600E (NM_004333.4 c.1799T>A, hereafter referred to as BRAF V600E), has been identified as a common finding in certain central nervous system (CNS) tumors, most notably in PXAs, (WHO grade II) and PXA-As, as well as in fewer numbers of gangliogliomas, extra-cerebellar pilocytic astrocytomas, and rarely, giant cell GBMs [1, 2, 3]. Because of the infrequency with which this mutation is seen in diffuse astrocytic tumors WHO grades II, III, and IV [3], it has been suggested that the presence of BRAF V600E may be helpful in distinguishing PXAs from histological mimics [2]. An unresolved issue, however, is whether age of patient may affect the percentage of tumors which are positive for this mutation. Schindler et al. found that 38% of adult PXA-As showed this mutation, compared to 100% of pediatric PXA-As [3].

In contrast, a common mutation in isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) is typical of the majority of diffuse astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas, and mixed oligoastrocytomas of WHO grades II and III as well as secondary glioblastomas (GBMs) [4, 5]. Primary GBMs almost never show mutation in IDH1, and PXAs, PXA-As, gangliogliomas, and pilocytic astrocytomas are also almost always negative for IDH1 mutation [4]. Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for IDH1 correlates strongly with the IDH1 mutational status as assessed by polymerase chain reaction testing [6] and thus can serve as a cost- and time-effective substitute for full mutational analysis assessment.

Amongst the most challenging histological tumors types to diagnose is the PXA-A. Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma (PXA) is a rare World Health Organization (WHO) grade II tumor, first fully characterized by Kepes et al. [7], that demonstrates a relatively favorable clinical course [7, 8, 9, 10]. PXA with anaplastic features (PXA-A) designates a subset that may show a more aggressive clinical course but has yet to be assigned a formal WHO grade [10]. Both PXAs and PXA-As are more common in children and young adults [7, 9, 10], but well-documented cases have been seen in patients 40 years or older [11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16]. PXA-A may arise de novo [17, 18], or may develop anaplastic features following recurrence of a previous WHO grade II PXA [12, 14, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23]. Recent reviews by Tekkök et al. [21], Okazaki et al. [22], and Vu et al. [23], underscore the fact that for either de novo PXA-As or PXA-As that secondarily-transform from PXA WHO grade II, prognosis is often, but not invariably, poor.

While PXA, WHO grade II, is unlikely to be mistaken for a GBM, PXA-As (a tumor more akin to WHO grade III) and GBMs (WHO grade IV) both share high grade features such as increased mitotic activity, and often necrosis. The WHO 2007 fascicle suggests that mitotic activity of greater than or equal to 5 mitoses per 10 high power fields (HPFs) best correlates with adverse prognosis in PXA, and thus should yield PXA-A diagnosis [10]. Necrosis also adversely affects survival [9, 24, 25, 26] and is frequently present in PXA-A. Most GBMs lack sufficient nuclear pleomorphism, cytoplasmic lipidization, reticulin-rich areas, or lymphocytic infiltrates [27] to cause diagnostic confusion with PXA-A for the pathologist. The exceptions to this, however, are two GBM subtypes: giant cell GBM (GC-GBM) and E-GBM.

GC-GBM is a well-described variant in WHO 2007 that manifests bizarre multinucleated giant cells, abundant reticulin investiture, often prominent lymphocytic infiltrates and cytoplasmic lipidization [27] and can be challenging to distinguish from PXA-A [28]. Genetically, GC-GBMs typically lack the EGFR amplification/overexpression of primary GBMs, but, like primary GBMs, approximately the same percentage (33%) share PTEN mutation. Up to 84% have TP53 mutation, a rate more parallel to secondary than primary GBMs [27]. Although TP53 mutational status is often not assessed in routine practice, positive TP53 mutational status can correlate with strong p53 nuclear immunohistochemical expression in glial tumors [29].

Epithelioid GBM (E-GBM) is rarer still than GC-GBM and is not a formal variant in 2007 WHO. E-GBMs are composed of cohesive sheets of patternless, closely-packed, variably lipidized, small- to medium-sized cells with rounded cytoplasmic profiles, eosinophilic cytoplasm, lack of cytoplasmic stellate processes, and absence of interspersed neuropil [30–36]. Tumors may additionally possess rich reticulin investiture but, unlike PXA-As, usually possess more cytologically-uniform cells and an absence of eosinophilic granular bodies [35].

In the current study, we tested the hypothesis that E-GBMs or GC-GBMs might possess the BRAF V600E mutation. Given the rarity of these subtypes of GBMs, we re-interrogated our originally published cohort of 8 E-GBMs and 2 rhabdoid GBMs [35] as well as 5 new E-GBM cases and 9 GC-GBMs from our files. The results of this report support our hypothesis that a significant percentage of E-GBMs, particularly (but not exclusively) those in young adults and children share the BRAF V600E genetic background of PXA, PXA-A, ganglioglioma, and extra-cerebellar pilocytic astrocytoma. In contrast, we were unable to identify the mutation in GC-GBMs or rhabdoid GBM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Case accrual

Institutional research review board approval was obtained for this study. Cases were identified by diagnosis from our pathology department databank and/or personal files of the authors for the years 2000–2011, inclusive, for E-GBMs and rhabdoid GBMs. Designations of E-GBM and rhabdoid GBM had not been utilized in our system prior to 2000 and thus were not retrievable by text word search of our databases prior to 2000. However, giant cell GBMs have existed as separate entities for a considerably longer time period and thus could be identified from the years 1994-present.

All slides were re-reviewed for diagnosis confirmation by the senior neuropathologist on the study (BKD); only cases where a predominant (>30–40%) tumor component manifested the E-GBM, rhabdoid GBM, or GC-GBM feature were utilized for this study. Cases in which slides or paraffin blocks were no longer available were excluded from the study.

In all examples, efforts were made to exclude the histological diagnosis of PXA-A. Criteria for diagnosis of PXA-A were employed, as detailed by Giannini et al. [9, 10]. As noted by Giannini et al., “although it was not stressed in the original description of PXA or in the WHO monograph, granular bodies of varying size, texture, and eosinophilia are a regular feature of this tumor [i.e., PXA-A]” [9]. In our own experience, the presence of multiple granular bodies, particularly the eosinophilic refractile type, within a tumor has been the single most helpful clue to diagnosis of PXA. None of our E-GBMs, GC-GBMs, or rhabdoid GBMs possessed multiple eosinophilic granular bodies. None possessed areas of classic low grade PXA juxtaposed to high grade glioma, as has previously been described in cases of PXA-A [25, 7].

Neuroimaging disks and original neuroimaging reports were available for review on all new E-GBM cases. Several of these patients were first seen for histological review of slides and diagnosis, following which, the patients were referred to our tertiary center for treatment considerations. Thus, additional neuroradiology interpretation from neuroradiologists within our system allowed comparisons between outside and in-house neuroimaging impressions.

Survival data had been recorded in our original cohort of 2 rhabdoid and 8 E-GBM patients recorded in that manuscript [35]. Followup information was sought in those known to be living at the time of that report. Survival was also investigated in all patients in whom the diagnosis had been made prior to 2009. However, the short (<3 years) interval between diagnosis and this report for new E-GBM and several GC-GBM cases made survival information for these more recently-diagnosed patients less meaningful. Where survival data could be obtained, however, this was anecdotally noted, with survival recorded as of 6/1/2012.

Methods for histology

For light microscopy, tumor sections were cut at 4 microns and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Immunohistochemistry for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, Dako, Carpinteria, CA, monoclonal, 1:100 dilution) and TP53 (Dako, monoclonal, 1:200 dilution) was conducted on the entire cohort, with synaptophysin (Ventana, Tucson, AZ, polyclonal, pre-dilute), neurofilament (Ventana, monoclonal, pre-dilute) and BAF-47 (INI-1 protein, BD Transduction, monoclonal, 1:250 dilution) immunostaining conducted additionally on all E-GBMs.

Immunostaining pattern for INI-1 was recorded as retained or lost in all nuclei or in a subset of tumor nuclei. Immunohistochemistry for IDH1 (Dianova HistoBio, Miami Beach, Florida, clone H09, monoclonal, 1:40 dilution) was recorded as positive or negative in tumor cell cytoplasm. p53 immunostaining was estimated semiquantitatively, with a score of 0 for <1%, 1+ given for 1% –5%, 2+ for 6%–25%, 3+ for 26%–50%, and 4+ for more than 50% of tumor cells showing immunoreactivity; TP53 immunostaining was conducted on E-GBMs as performed in the study by Rodriguez et al. [33]. Efforts were made to exclude non-tumoral vascular, stromal cells and hematopoietic cells in the semiquantitative estimates.

Immunohistochemistry for IDH1 was conducted on all cases except 3 instances where insufficient tissue remained (cases 2, 5, 9, see Table). IDH1 IHC was of uniform pattern throughout the tumor and was either positively expressed in cytoplasm of all tumor cells, or negative in all tumor cells.

Scoring for immunohistochemical features for all tumors with BRAF mutation

Paralleling our original study on E-GBMs, scoring of extent/severity of necrosis, lymphocytes, and reticulin fibers between individual or small groups of tumor cells was assessed after Gomori reticulin stain. Presence or absence of synaptophysin or neurofilament immunostaining was assessed. Scoring for these features was performed as in our previous study [35]:

Necrosis was semi-quantitatively assessed on a 0–3+ scale, with 0 indicating no necrosis present on the biopsy/resection specimen, 1+ indicating focal small areas of necrosis, and 2+ indicating multifocal broad zones of necrosis or pseudopalisading necrosis present. A score of 3+ was reserved for cases with extensive necrosis, estimated to occupy 10% or more of the sampled specimen. Inflammation (lymphocytes) within the tumors was scored as absent (0), focally present (1+), or prominent (2+). Reticulin fiber deposition between individual or small groups of tumor cells was assessed after Gomori reticulum stain and recorded as being absent (0), focally present (1+), or focally prominent (2+) between tumor cells. Where this change was focally present, it was noted as such. Immunostaining for synaptophysin and neurofilament was recorded as being absent (0) or focally present (1+).

Methods for fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) had been conducted as part of the routine workup at the time of diagnosis in most cases. Briefly, dual-color FISH probe sets, manufactured by Vysis (Abbott Laboratories Inc., Des Plaines, IL, USA), were used for loss of heterozygosity studies of chromosome 1p36 and 19q13, and amplification status of EGFR. The probe sets were: chromosome 1p36 (Spectrum Orange) and 1q25 (Spectrum Green); chromosome 19p13 (Spectrum Green) and 19q13 (Spectrum Orange); EGFR (7p12-Spectrum Orange) and CEP7 (D7Z1-Spectrum Green). To test for monosomy 22, DNA probes directed to 22q11.2 and 22q13 were used; this method detects most deletions but does not detect point mutations in chromosome 22. For analysis of PTEN, a PTEN (10q23)-specific DNA probe and a probe directed to the chromosome 10 centromere were used.

Methods for V600E BRAF mutational analyses

Most cases had unstained slides available for microdissection by one of the authors, although in several instances immunonegative slides prepared at the time of original diagnosis remained the only available material for microdissection (DLA). Tumor tissues with epithelioid, rhabdoid, or giant cell morphology were specifically identified, circled by the neuropathologist (BKD), and targeted for microdissection and assessment. In two pediatric cases, tumor DNA prepared from frozen tissue obtained at the time of surgical excision was additionally available for mutational testing (cases 16, 17, both pediatric GC-GBMs). Thus, two samples could be tested from two differing areas of tumor for BRAF V600E, i.e., from tumor DNA and from microdissection paraffin-scraped material.

In the case of the material microdissected from slides, paraffin sections were thoroughly deparaffinized in xylene, hydrated through graded alcohols to water and stained with Gill’s hematoxylin. Slides were covered with glycerol to prevent cell dispersion and isolated under dissecting microscope using a scalpel point or hollow borosilicate glass pipette. The scraped material was washed in PBS and digested in proteinase K overnight at 37°C in ATL Buffer (Qiagen Inc.). DNA was then isolated using QIAamp DNA FFPE extraction kit (cat # 56404) according to manufacturer instructions.

In the case of paraffin tissue blocks (one case), paraffin scrolls were deparaffinized in xylene as above, followed by reconstitution in graded alcohols and PBS and treated in parallel fashion. DNA yields were then quantified using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer ND-1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA).

For direct sequencing, approximately 10 ng of template DNA was PCR amplified using 5 pmol each of forward (5’TGCTTGCTCTGATAGGAAAAT3’) and reverse (5’TCAGGGCCAAAAATTTAATCA3’) BRAF exon 15 primers KAPA2G™ Robust HotStart Enzyme and PCR master mix with KAPA™ dNTP mix (KAPA Biosystems cat# KK5525 and KK1017) in a 25µl reaction. PCR was performed on an ABI 9700 thermocycler with an initial denaturing step at 95°C followed by 20 cycles of touchdown PCR (starting annealing temperature of 65°C, decremented 0.5°C per cycle) and 25 cycles at 94°C denaturation, 55°C annealing and 72°C extension finished by a 10 minute 72°C final extension. The resultant PCR products were purified with the QIAquick 96 well PCR cleanup kit (Qiagen cat# 28106). The purified PCR products were sequenced in forward and reverse directions using an ABI 3730 automated sequencer using BigDye Terminator Version 1.1 (Applied Biosystems). Each chromatogram was visually inspected for any abnormalities, using NM_004333.4 as a reference sequence, with particular attention directed to codon 600. Sequences were also evaluated using Mutation Surveyor software (Soft Genetics, State College, PA). Mutations were determined to be present when peaks reached a threshold value above baseline calculated from background level, combined with visual inspection of the chromatogram.

RESULTS

Demographic features of cohort

Demographic, clinical, treatment, and histological features are detailed in Table 1. A total of 24 patients were studied (11 females, 13 males). Patients ranged in age from 4–67 years for the entire cohort, with the two rhabdoid GBMs being ages 18 and 67 years [35]. No additional, new examples of rhabdoid GBMs were identified for inclusion. Of the 13 total E-GBMs, 5 represented new cases since our original study, i.e., these patients were newly diagnosed since 2009 and of these, 3 of the 5 were consultation cases (see Table 1). Within the E-GBM cohort (n=13), patient ages ranged from 10–69 years, with 9/13 patients less than age 30 years. Three of these patients were pediatric, as defined by ages 18 years or less at time of diagnosis (cases 5, 10, 13; see Table 1). One patient had a past diagnosis of a mixed oligoastrocytoma 2 years antecedent to his E-GBM; this case was recorded as a secondary E-GBM (case 8). The remaining 12 E-GBMs were primary GBMs, i.e., occurred de novo. Of the 9 GC-GBMs, 8 were primary/de novo GBMs and one was secondary (case 22). Patients with GC-GBMs had ages ranging from 4–63 years; the 2 pediatric patients were ages 4 and 16 years (cases 16, 17, respectively).

Table 1.

| TABLE CLINI CAL, IMMUNOHISTOCHEMICAL, MOLECULAR AND CYTOGENETIC FEATURES | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient age, gender, year of surgical biopsy/resection. C= consultation case Tumor location/ Surgical Procedure |

Diagnosis |

BRAF V600E Mutational status |

BAF47 (INI-1) IHC |

FISH for EGFR, PTEN, monosomy 22, LOH 1p, 19q |

p53; IDH-1 IHC |

Clinical outcome/ Interval to Demise or Survival |

|

| RHABDOID GLIOBLASTOMAS | |||||||

| 1 | 18 M 1999 Right frontal Resection |

Primary rhabdoid GBM |

No mutation present |

BAF47 Focally lost in nuclei of rhabdoid cells, but not in non rhabdoid areas |

Negative for EGFR amplification Monosomy 22 demonstrated on culture as minor clone |

p53 1+ IDH-1 negative |

Died 22 weeks Autopsy showed residual tumor in right frontal lobe, adjacent leptomeninges Implantation metastasis in right frontoparietal scalp, microscopic metastases in both lungs |

| 2 | 67 F 2007 C Right occipital lobe Resection |

Primary rhabdoid GBM |

No mutation present |

BAF47 Focally lost in nuclei of rhabdoid cells, but not in non rhabdoid areas |

Positive for high level amplification EGFR Positive for loss of PTEN (10q23) sequences Positive for loss of 22q11.2 and 22q13 sequences, consistent with monosomy 22 (genetic findings present in both histologically rhabdoid and non rhabdoid areas) |

p53 2+ IDH-1 not tested due to inadequate tissue |

Died 36 weeks |

| EPITHELIOID GLIOBLASTOMAS | |||||||

| 3 | 24M 1997 C 1997 (2 surgical procedures same year) Right temporal Biopsy Resection |

Primary epithelioid GBM |

No mutation present |

BAF47 Retained in all tumor nuclei |

Negative for EGFR amplification |

p53 2+ IDH-1 negative |

Developed cerebrospinal fluid dissemination (+ CSF cytology) Died 25 weeks |

| 4 | 27 F 2001 Left occipital Resection |

Primary epithelioid GBM |

V600E mutation present |

BAF47 Retained in all tumor nuclei |

Positive for cells with EGFR amplification |

p53 4+ IDH-1 negative |

Alive as of 5/1/08 328 weeks |

| 5 | 18M 2002 C Right frontoparietal Resection |

Primary epithelioid GBM Patient with lower limb amputation for developmental anomaly, recurrent Burkitt lymphoma of gastrointestinal tract Known germline short arm chromosome 22 abnormality |

No mutation present |

BAF47 Retained in all tumor nuclei |

Negative for EGFR amplification |

p53 4+ IDH-1 not tested due to inadequate tissue |

Alive as of 3/31/09 267 weeks Lost to followup after 2009 |

| 6 | 25 M 2003 C Cerebellar hemisphere Resection |

Primary epithelioid GBM |

No mutation present |

BAF47 Retained in all tumor nuclei |

Negative for monosomy of Ch. 22 |

p53 4+ IDH-1 negative |

Died 66 weeks |

| 7 | 43 M 2003 C Left temporal- Parietal Resection |

Primary epithelioid GBM |

V600E mutation present |

BAF47 Retained in all tumor nuclei |

Negative for monosomy of Ch. 22 |

p53 1+ IDH-1 negative |

Died 10/23/03 26 weeks |

| 8 | 41 M 2003 Right frontal Resection |

Secondary epithelioid GBM arising as a well- demarcated enhancing mass in cavity of previous surgical resection bed Previous mixed oligoastrocytoma WHO grade II, 2 years prior |

No mutation present |

BAF47 Retained in all tumor nuclei |

Negative for monosomy of Ch. 22 Negative for LOH 1p, 19q (testing performed on epithelioid glioblastoma) |

p53 4+ IDH-1 positive |

Alive as of 8/1/09 306 weeks Alive as of 6/1/12 |

| 9 | 69 M 2007 C Left frontal lobe Biopsy |

Primary epithelioid GBM |

No mutation present | Not tested due to inadequate tissue |

Not tested | p53 not tested due to inadequate tissue IDH-1 not tested due to inadequate tissue |

Died 85 weeks |

| 10 | 10 F 2009 2009 (2 surgical procedures same year) Right parieto-occipital Biopsy Resection |

Primary epithelioid GBM |

V600E mutation present |

BAF47 Retained in all tumor nuclei |

Negative for EGFR amplification Negative for loss of PTEN (10q23) sequences Negative for monosomy of Ch. 22 |

p53 2+ IDH-1 negative |

Alive as of 8/1/09 24 weeks Alive as of 6/1/12 |

| 11 | 29 M 2012 Left temporal lobe Resection |

Primary epithelioid GBM |

V600E mutation present |

BAF47 Retained in all tumor nuclei |

Negative for EGFR amplification Low level loss of PTEN and 10 centromere consistent with monosomy 10 Negative for monosomy of Ch. 22 |

p53 1+ IDH-1 negative |

Alive as of 6/1/12 |

| 12 | 21 F 2012 C Right temporal lobe Resection |

Primary epithelioid GBM |

V600E mutation present |

BAF47 Retained in all tumor nuclei |

Negative for amplification of EGFR sequences Negative for loss of PTEN sequences Weak EGFR expression |

p53 1+ IDH-1 negative |

Alive as of 6/1/12 |

| 13 | 14 M 2011 Right frontal lobe Biopsy |

Primary epithelioid GBM |

No mutation present |

BAF47 Retained in all tumor nuclei |

Rare cells with amplification of EGFR (1.8%); other cells with polysomy (3–4, 43.6%), and high polysomy for Ch. 7 (>5, 35.0%) Borderline for loss of PTEN and 10 centromere, suggesting monosomy 10 Negative for monosomy of Ch. 22 |

p53 0 IDH-1 negative |

Alive as of 6/1/12 |

| 14 | 29 F 2012 C Left temporal-parietal lobe Resection |

Primary epithelioid GBM |

V600E mutation present |

BAF47 Retained in tumor nuclei |

Negative for amplification of EGFR sequences Positive for loss of PTEN and 10 centromere sequences, consistent with monosomy 10 |

p53 2+ IDH-1 negative |

Alive as of 6/1/12 |

| 15 | 50 M 2012 Left temporal lobe Resection C |

Primary epithelioid GBM |

V600E mutation present |

BAF47 Retained in tumor nuclei |

Negative for amplification of EGFR sequences Positive for loss of PTEN and 10 centromere sequences, consistent with monosomy 10 |

p53 1+ IDH-1 negative |

Alive as of 6/1/12 |

| GIANT CELL GLIOBLASTOMAS | |||||||

| 16 | 4 F 2008 (2 surgical procedures same year) 2009 Right temporal lobe Resection |

Primary GBM, giant cell variant |

No mutation present | Not tested | Not tested | p53 1+ IDH-1 negative |

Alive as of 6/1/12 |

| 17 | 14 F 2002 (2 surgical procedures same year) Biopsy Resection |

Primary GBM, giant cell variant |

No mutation present | Not tested | Not tested | p53 4+ IDH-1 negative |

Died 72 weeks |

| 18 | 47 M 2008 (biopsied 2007, misdiagnosed as metastatic sarcoma, given stereotactic radiosurgery; on review GC-GBM) Previous maxillary sinus osteosarcoma resected 2001 Right occipital lobe Resection |

Primary GBM, giant cell variant |

No mutation present | Not tested | Positive for gain of chromosome 7 Positive for loss of chromosome 10 (including PTEN) Negative for amplification of EGFR (7p12) |

p53 4+ IDH-1 negative |

Alive as of 6/1/12 * |

| 19 | 69 F 2002 Parieto occipital lobe (side unspecified) Resection |

Primary GBM, giant cell variant |

No mutation present | Not tested | Not tested | p53 3+ IDH-1 negative |

|

| 20 | 45 F 2000 2005 Left temporal lobe Resections |

Primary GBM, giant cell variant |

No mutation present | Not tested | No evidence of amplification of EGFR (7p12) sequences Negative for deletion of 1p36 sequences (ratio 1p36:1q25=1.06) Negative for deletion of 19q13 sequences (ratio 19q13:19p13=1.11) |

p53 0 IDH-1 negative |

Alive as of 6/1/12 |

| 21 | 31 M Left frontal lobe Resection |

Primary GBM, giant cell variant |

No mutation present | Not tested | Not tested | p53 3+ IDH-1 negative |

|

| 22 | 60 F 2012 2011 2008 dx’d as grade III astrocytoma, outside hospital Right frontal lobe Resection |

Secondary GBM, giant cell variant |

No mutation present | Not tested | Positive for amplification of EGFR sequences Negative for loss of PTEN sequences |

p53 4+ IDH-1 negative |

Alive as of 6/1/12 |

| 23 | 50 F 2010 2008, dx’d as GBM, outside hospital Right parietal lobe Resection |

Primary GBM, giant cell variant |

No mutation present | Not tested | Negative for deletion of 1p36 sequences (ratio p36:1q25=0.93) Negative for deletion of 19q13 sequences (ratio 19q13:19p13=0.92) Positive for amplification of EGFR sequences Positive for loss of PTEN and 10 centromere, consistent with monosomy 10. |

p53 0 IDH-1 negative |

Alive as of 6/1/12 |

| 24 | 63 M 1998 Left posterior frontal lobe Biopsy |

Primary GBM, giant cell variant |

No mutation present | Not tested | Not tested | p53 0 IDH-1 negative |

|

Key: M=male, F=female, IHC=immunohistochemistry, ND=not done, GBM=glioblastoma, Ch.=chromosome

case 4 was seen in consultation by neuropathologists at Mayo Clinic, Duke, and Johns Hopkins; diagnoses were glioblastoma with epithelioid features (consultant notes that “no definite pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma component is present”); glioblastoma with abundant reticulin; malignant glioma with features of epithelioid glioblastoma

case 8 was seen at Duke prior to entering a treatment protocol and diagnosed as glioblastoma

case 18 maxillary sinus lesion seen in consultation by soft tissue pathologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and diagnosed as osteosarcoma, chondroblastic type, grade 2 of 3; *= this patient survived at study closure date but succumbed 9/2012 (note added in proof)

IHC scoring for p53: 0 (<1%), 1+ (1–5% cells immunoreactive); 2+ (6–25% immunoreactive); 3+ (26–50% immunoreactive); 4+ (>50% cells immunoreactive)

Survival features of cohort

Although survival data had been calculated for our original E-GBM and rhabdoid GBM cohort (35), the followup was less than 3 years (i.e., diagnosis made since 2009, or later) for all of our new E-GBMs and thus likely not meaningful. All 5 new E-GBMs are alive at the time of study closure (6/1/12). Anecdotally, from our original study, cases 4 (diagnosed 2001), 8 (diagnosed 2003 as secondary E-GBM), and 10 (diagnosed 2009) are also known to be alive as of study closure date. Case 5, who was alive at the time of our original report [35], has been lost to followup. Both rhabdoid GBMs succumbed quickly to their disease and were so reported in our original study [35]. Survival times have been noted in the current manuscript in Table 1.

One of the two pediatric patients with GC-GBMs is currently alive (diagnosed in 2008, case 16). Several of the adult GC-GBM patients also survive as of the study closure date: case 20 (diagnosed in 2000, recurrence in 2005) and case 23 (diagnosed in 2010 and treated on experimental vaccine protocol). Case 18 (diagnosed in 2008) was alive and in hospice as of study closure date, but recently succumbed in 9/2012 (note added in proof). Numbers were obviously too small to provide meaningful data, but did suggest that some GC-GBMs also enjoy longer survival times.

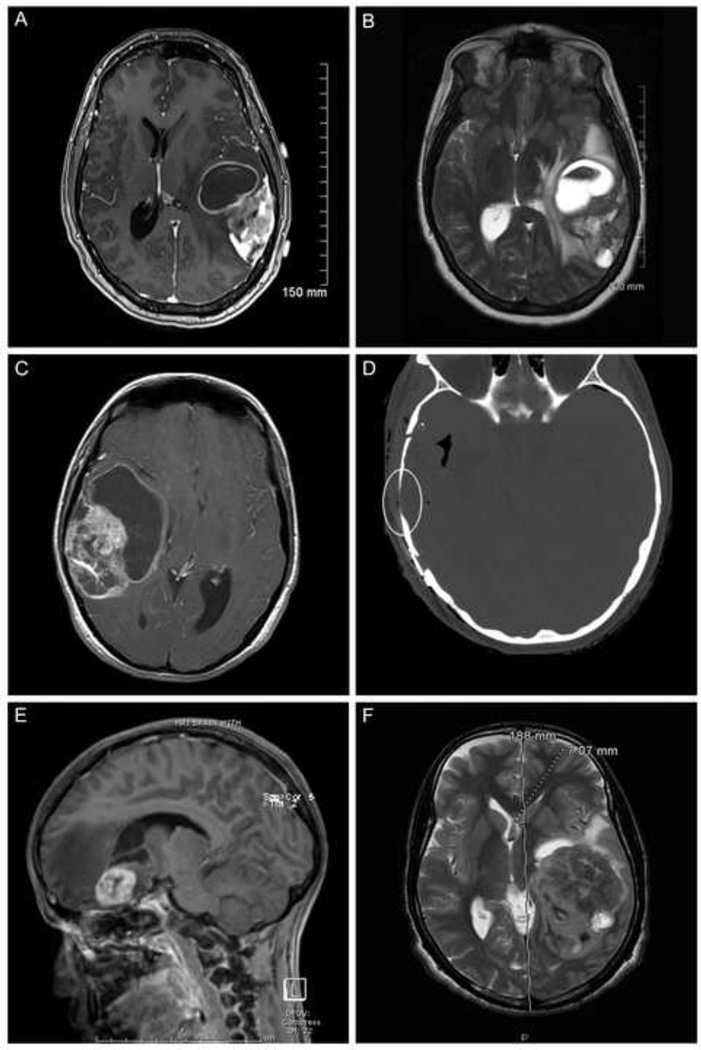

Neuroimaging features of new E-GBMs

Neuroimaging features, where known, had been illustrated in our original cohort (Figure 1, see reference 35). Neuroimaging information was acquired for all 5 new E-GBMs. All 5 new E-GBM cases showed large tumors with complex cystic and solid enhancing areas (Figure 1 a-f). None showed a simple mural nodule-cyst configuration. Despite the fact that none of the 5 new E-GBMs had a clinical history of an antecedent low grade glioma (i.e., none fit clinical criteria for secondary E-GBMs), 2 of the 5 original neuroimaging reports we obtained mentioned possible, or definite, bony changes in adjacent skull, suggesting antecedent low grade or long-standing tumors had existed before the E-GBM was diagnosed/became clinically obvious (cases 13, 14). Specifically, the original neuroimaging report on case 13 noted that “the skull over the right frontal lobe is equivocally minimally thinner than the left, with less of a marrow space identified on several images, although this finding is subtle and not definite”. Case 14 had a neuroimaging report that noted “mild remodeling of the overlying skull” and this was confirmed on review of neuroimaging studies here from this consultation case. Case 12 had no mention of bony changes in the original report, but on detailed review here of her studies, after referral to our institution, significant bony changes were identified (Figure 1d). Case 11 had no bony changes, either on the original report, or on review.

Figure 1.

A. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, axial, T1-weighted with gadolinium enhancement shows an E-GBM with complex cystic and solid enhancing areas; none of the 5 new E-GBMs cases in this study showed a simple mural nodule-cyst configuration. Case 14 illustrated.

B. MRI, axial, T2-weighted scan, better highlights the bright signal in the cystic portions of this same E-GBM, as well as the surrounding edema and midline generated by this high grade tumor. Case 14 illustrated.

C. MRI scan, axial, T1-weighted with gadolinium, from another E-GBM shows an even larger cystic component in this example. Case 12 illustrated.

D. Computerized tomographic scan, axial, shows the nearby bony thinning (encircled) in this same patient, suggesting a more longstanding tumor had been present. Despite this radiographic feature, low grade tumor areas were not identified in the resection specimen. Case 12 illustrated.

E. MRI scan, sagittal, T1-weighted with gadolinium, shows a small cystic component and more solid, relatively well-demarcated enhancing component in this pediatric patient with E-GBM; note the significant surrounding edema (dark intensity signal). Case 13 illustrated.

F. MRI scan, axial, T2-weighted, highlights the massive size of some of these E-GBMs, as measured on the scan, as well as the extent of midline shift that can be produced. Case 11 illustrated.

Retrospective correlation of BRAF results with neuroimaging features of new E-GBMs

After receipt of BRAF results, we attempted to correlate the bony changes with the BRAF mutational status to see if this radiological feature might predict mutational status and preempt the need for mutational analysis. Case 13 and case 14 both had mild skull changes that suggested the possibility of more long-standing tumor; these cases did and did not, respectively, possess the mutation (see below and Table 1). Case 12 had bony changes only on detailed review; she was positive for the mutation. Case 11 had no bony changes and was negative for the mutation. Thus, based on a very small number of cases, there was no correlation between neuroimaging features of bony thinning or erosion and BRAF V600E status. The degree of surrounding edema also varied, with significant midline shift seen in case 11 (Figure 1e), but relatively little edema surrounding the tumor in case 15. Hence, extent of edema was also not predictive of BRAF status for individual patients.

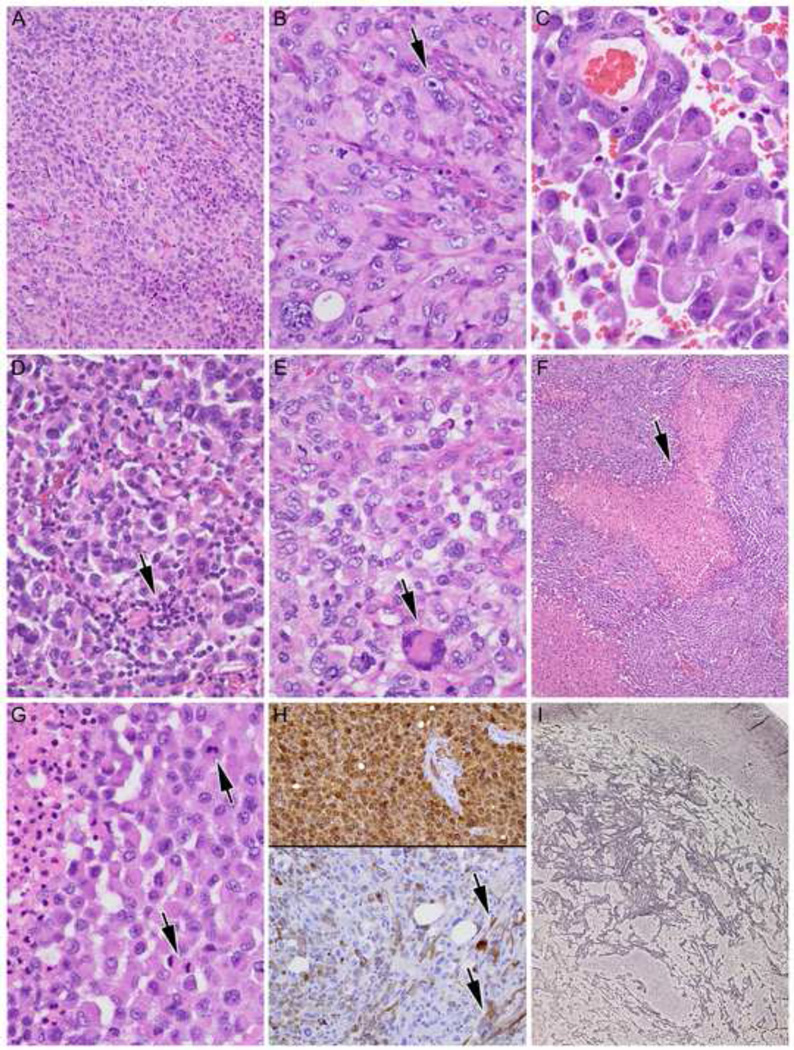

Histological features of E-GBMs

Histological features of E-GBMs and rhabdoid GBMs were detailed in our original report [35]. Features of E-GBMs were recapitulated in the 5 new cases and further illustrated here. E-GBMs were characterized by relatively monotonous sheets of small- to moderate-sized epithelioid cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm with rounded cell borders and a paucity of stellate cytoplasmic processes (Figure 2A–G). At higher power magnification, prominent nucleoli and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm could be seen, sometimes mimicking a rhabdoid phenotype (Figure 2B, arrowhead). Discohesive tumor cells could lead to areas almost identical to metastatic carcinoma or melanoma (Figure 2C). Variable numbers of accompanying non-neoplastic lymphocytes (arrow) added to the diagnostic overlap, at least focally, with metastatic carcinoma or melanoma (Figure 2D). E-GBMs in most cases showed almost complete cellular monotony (cases 11, 12, 15), although slightly more variation in cellular size and scattered larger, sometimes multinucleated (arrowhead) cells could be identified, as shown in case 13 (Figure 2E). Necrosis (arrow) was identified in 4 of 5 new E-GBMs (Figure 2F, 2G). Multiple mitotic figures (arrows) were found in all examples (Figure 2G). Strong diffuse S100 immunoreactivity (top) with more variable and patchy GFAP immunostaining (bottom) was typical of E-GBMs (Figure 2H). In one case (case 14), focal spindled morphology of some cells was highlighted by GFAP (Figure 2H, arrows). Increased reticulin fiber deposition could be found in E-GBMs, but was often quite focal (Figure 2I).

Figure 2.

A. E-GBMs were characterized by relatively monotonous sheets of small- to moderate-sized epithelioid cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm with rounded cell borders and a paucity of stellate cytoplasmic processes. Case 14 illustrated, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), 200X.

B. At higher power magnification, prominent nucleoli (arrowhead) and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm could be seen, mimicking a rhabdoid phenotype. Case 14 illustrated, H&E, 400X.

C. Discohesive tumor cells could lead to areas almost identical to metastatic carcinoma or melanoma. Case 12 illustrated, H&E, 600X.

D. Variable numbers of accompanying non-neoplastic lymphocytes (arrow) add to the diagnostic overlap, at least focally, with metastatic carcinoma or melanoma. Case 15 illustrated, H&E, 400X.

E. E-GBMs in most cases showed almost complete cellular monotony (cases 11, 12, 15), although slightly more variation in cellular size and scattered larger, sometimes multinucleated (arrowhead) cells could be identified. Case 13 illustrated, H&E, 400X.

F. Necrosis (arrow) was identified in 4 of 5 new E-GBMs. Case 11 illustrated, H&E 100X.

G. Multiple mitotic figures (arrows) were found in all examples; note necrosis at higher magnification from this same patient at left. Case 11 illustrated, H&E 600X.

H. Strong diffuse S100 immunoreactivity (top) with more variable and patchy GFAP immunostaining (bottom) is characteristic of E-GBMs. Note spindled morphology of some cells on GFAP (arrows). Case 14 illustrated, both 200X, immunohistochemistry with light hematoxylin counterstain for S100 protein and glial fibrillary acidic protein.

I. Foci with increased reticulin fiber deposition were often found in E-GBMs. Case 15 illustrated, Gomori’s reticulum stain, 40X.

In terms of extent of these features, necrosis was extensive in cases 11 and 12 (scored as 3+), moderate in cases 13 and 14 (scored as 2+), and absent in case 15 (scored as 0), which had focal microvascular proliferation to meet WHO GBM criteria. Lymphocytic collections were absent in 1 case (case 13), focally present in cases 11 and 14 (scored as 1+), and focally prominent in cases 12 and 15 (scored as 2+). Reticulin fiber deposition between individual or small groups of tumor cells as assessed after Gomori reticulum stain was recorded as being absent in case 12 (scored as 0), focally present in case 11 (scored as 1+), or focally prominent in cases 13, 14, 15 (scored as 2+).

Immunohistochemical features of E-GBMs

Synaptophysin immunoreactivity was identified in rare cells (scored as 1+) only in cases 12 and 15 with rare cells immunoreactive for neurofilament only in cases 12 and 14 (scored as 1+). Thus, the current cohort extended our previous findings [35] that necrosis, lymphocytic collections, increased reticulin fiber deposition, and occasionally rare cells immunoreactive for neuronal markers were features of at least many E-GBMs, although all features were not found in all tumors.

Four of our 12 assessable E-GBMs showed strong (i.e., 3+ or 4+) immunoreactivity to p53, as did 5/9 of our GC-GBMs, as expected (see Table 1 and summary Table 2). All E-GBMs, showed uniform retention of BAF-47 (INI-1) immunostaining throughout the tumor, in contrast to the rhabdoid GBMs where focal loss was seen in both, as illustrated in our previous publication [35]. None of the de novo E-GBMs showed IDH1 immunoreactivity; the sole case with IDH1 immunoreactivity was the secondary E-GBM. Both R-GBMs showed low p53 immunostaining.

Table 2.

Summary of study results

| Tumor type | BAF47 (INI-1) IHC |

p53 IHC strongly overexpressed (3+ or 4+ immunostaining) |

BRAF V600E mutation present |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=13 | E-GBMs | Retained in all tumor nuclei in all 13 cases |

4 of 12 cases | 7 of 13 cases |

| N=9 | GC-GBMs | Not done | 5 of 9 cases | 0 of 9 cases |

| N=2 | R-GBMs | Focally lost in nuclei of rhabdoid cells in 2 of 2 cases |

0 of 2 cases | 0 of 2 cases |

p53 immunostaining (IHC) was estimated semiquantitatively, with a score of 0 for <1%, 1+ given for 1% –5%, 2+ for 6%-25%, 3+ for 26%–50%, and 4+ for more than 50% of tumor cells showing immunoreactivity

Fluorescence in situ hybridization results

Genetic studies utilizing FISH revealed that 1 of 2 rhabdoid GBMs, 3 of 9 tested E-GBMs, and 2 of 4 tested GC-GBMs had EGFR amplification (Table 1). PTEN loss had predominantly been evaluated as part of the diagnostic workup in more recently diagnosed tumors, and of the 6 recent E-GBMs tested for PTEN loss, 2 were positive and one had low level loss (see Table 1). Thus, FISH results were not uniform within the BRAF-mutant E-GBM cohort and did not appear to show correlation with BRAF status (see Table). The rhabdoid GBMs manifested monosomy 22. The sole secondary E-GBM arising from a mixed oligoastrocytoma was negative for LOH 1p, 19q (see Table 1).

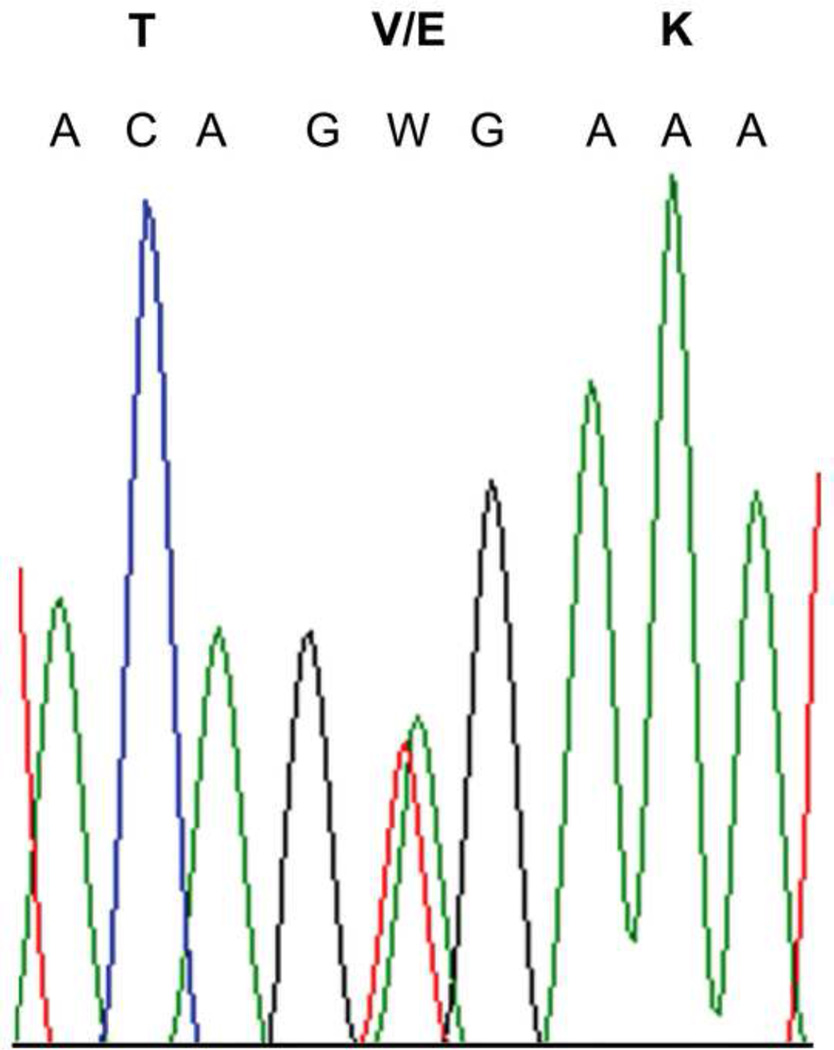

BRAF V600E mutational results in cohort

Four of the 5 new E-GBMs were positive for the BRAF V600E mutation (cases 11, 12, 14, 15, see Table 1). Three of our original E-GBMs were found in retrospect to possess the BRAF V600E mutation (cases 4, 7, 10) and clues existed in the E-GBM of case 4 that features overlapped with PXA-A. Indeed, because of concern for PXA-A on our part, case 4 had been seen in consultation originally by neuropathologists at Mayo Clinic, Duke, and Johns Hopkins and diagnosed as “no definite pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma component is present”; glioblastoma with abundant reticulin; and malignant glioma with features of epithelioid glioblastoma [35]. Case 10 from our original study [35] had neuroimaging features suspicious for PXA-A with a cyst and mural nodule configuration (see Figure 1, E, F from original paper [35]. However, it should be pointed out that other E-GBMs from our original cohort also showed unusual degrees of circumscription, dural attachment, or even cystic appearance [35] and were not found in this current study to possess the BRAF V600E mutation. While acknowledging that the small numbers of cases in the cohort precluded any meaningful statistical analysis or any definitive conclusions, our observation was that the extent/scoring of histological features of E-GBMs, e.g., how extensive the lymphocytic infiltrates or reticulin fibers were, did not reliably predict BRAF mutational status for any given tumor. In addition, TP53 IHC score and FISH results were not uniform within the BRAF-mutant E-GBM cohort (see Table 1). TP53 IHC scores tended to be lower as a whole in E-GBMs than GC-GBMs.

All rhabdoid and GC-GBMs showed an absence of BRAF V600E mutation, including the two pediatric GC-GBMs doubly assessed on frozen tumor DNA sample and after microdissection from a paraffin slide. Table 2 summarizes these BRAF results.

Electropherogram demonstrating a representative example of c.1799T>A (p.V600E) mutation identified in case 11, with nucleotide and amino acid designations indicated, is provided as a representative example in Figure 3; other positive cases appeared identical on electropherogram.

DISCUSSION

The current study demonstrates that a significant percentage (7/13 cases, 54%) of E-GBMs possess the BRAF V600E mutation. While there are definitely areas of neuroimaging and histological overlap between E-GBMs and PXA-As, there are also many differences. E-GBMs usually show complex neuroimaging features with multiple cysts and enhancing nodular tumor masses (see Figure 1), but some overlap with the simple cyst and mural nodule configuration of many PXAs [10] does exist (case 10, illustrated in our previous manuscript [35]. Histologically, PXA-As and E-GBMs often share features of dural attachment, lymphocytic infiltrates, and reticulin-rich areas, as shown in this study, but the absence of classic lower grade PXA areas anywhere in E-GBMs, the relatively monotonous, epithelioid tumor morphology in large areas of E-GBMs but not PXA-As, and the absence of significant numbers of eosinophilic granular bodies in E-GBMs has led many pathologists and neuropathologists to diagnose E-GBMs as separate entities [30–36].

The finding of BRAF V600E mutation in both E-GBMs and PXA-As does not prove that these tumors are identical, any more than finding the common genetic BRAF V600E mutational background in PXA, WHO grade II, PXA-A, gangliogliomas, and extracerebellar pilocytic astrocytomas [1–3] proves that all these tumor types are equivalent to each other. Presence of a common genetic BRAF V600E mutational background also does not correlate with tumor grade since PXA-As and E-GBMs are malignant gliomas, PXA is WHO grade II, and gangliogliomas and extracerebellar pilocytic astrocytomas are WHO grade I.

We were unable to identify a single “signature” demographic, neuroimaging or histological feature that was common to all BRAF-mutant E-GBMs that might obviate the need to perform BRAF mutational analysis testing. In addition, TP53 IHC score and FISH results were not uniform within the BRAF-mutant E-GBM cohort (see Tables 1 and 2). We did note, however, that the majority of GC-GBMs (5 of 9) and 1/3 of E-GBMs (4 of 12 assessed) showed strong (3 or 4+ p53 IHC), whereas neither R-GBM showed this feature (Table 1 and Table 2). PXA-As may be histologically difficult to distinguish from either GC-GBMs or other types of GBMs [28, 2]. When present, strong p53 IHC may be an additional feature that aids in the differential diagnosis of GC-GBM or E-GBM from PXA-A, since a significant percentage of both GC-GBMs and E-GBMs show strong p53 IHC expression while only a minority of PXA-As strongly over-express p53 by IHC [28] or show TP53 mutation [37].

We included GC-GBMs and rhabdoid GBMs for investigation of BRAF V600E mutational status. None of the cases in our cohort diagnosed as GC-GBMs or rhabdoid GBMs showed the mutation. We fully acknowledge that larger studies from other institutions will be necessary to verify our result in GC-GBMs. Given previous reports [2, 3], we anticipate that other groups may have a few GC-GBMs in their practice that do possess this mutation. However, it does not appear that GC-GBMs as a group are as significantly enriched for this mutation as are E-GBMs. It should also be noted that some studies show up to 25% of GC-GBM are mutated for IDH1 [4]; none of the GC-GBMs in our series were IDH-1 immunopositive. GC-GBMs could conceivably have heterogenous genetic origins.

It should also be emphasized that absence of BRAF mutation does not negate a histological diagnosis of either PXA-A or E-GBM. Indeed, while 100% of our E-GBMs did not show BRAF V600E mutation, neither do 100% of PXAs or PXA-As, as reported in studies performed by several different groups worldwide using current WHO diagnostic criteria for these diagnoses [1, 2, 3]. Schindler et al. investigated a large number of PXAs (64: 38 adult, 26 pediatric) and PXA-As (23: 13 adult; 10 pediatric) and found the mutation in 66% of PXAs overall (63% adult, 69% pediatric) and 65% of PXA-As (38% adult, 100% pediatric) [3]. Dias-Santagata et al. found the mutation in 60% of WHO grade II PXAs, but only in 17% of PXA-As, although a small number of the latter were assessed [2]. Based on these studies from several different groups, at least one-third of bona fide PXAs and PXA-As appear to be definitively negative for BRAF V600E mutation and it is currently unclear if one, or more, as-yet-undiscovered genomic alterations might be present in this subset without BRAF V600E mutation. A similar percentage of E-GBMs in this study were also negative for BRAF V600E mutation.

In metastatic melanoma, the presence of BRAF mutation strongly correlates with young patient age, with all patients <30 years and only 25% of those >/= 70 years having BRAF-mutant melanoma [38]. In the current study of E-GBMs, 5 of 7 E-GBM patients with BRAF V600E mutation were <30 years of age, although a 43-year-old man and a 50-year-old man with E-GBM each possessed BRAF-mutant tumor.

Testing for BRAF V600E mutational status may prove to be of more than passing academic interest in E-GBMs, PXAs, and PXA-As that require treatment in addition to surgical resection. Studies have shown the effectiveness and specificity of PLX4032 (vemurafenib), an FDA (Federal Drug Administration)-approved kinase inhibitor used for targeted treatment of metastatic melanoma [39, 40], and suggested its potential use in the treatment of brain tumors harboring the BRAF V600E mutation [41].

Figure 3.

Electropherogram demonstrating a representative example of c.1799T>A (p.V600E) mutation identified in 4 of 4 new E-GBM cases, with nucleotide and amino acid designations indicated. Case 11 illustrated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Mrs. Diane Hutchinson for excellent manuscript preparation and Ms. Lisa Litzenberger for expert photographic assistance

Footnotes

Accepted for abstract presentation at the 52nd annual meeting of the Canadian Association of Neuropathologists, October 24th – 27th, Mont-Tremblant, Quebec

DISCLOSURE/CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dougherty MJ, Santi M, Brose MS, et al. Activating mutations in BRAF characterize a spectrum of pediatric low-grade gliomas. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12:621–630. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dias-Santagata D, Lam Q, Vernovsky K, et al. BRAF V600E mutations are common in pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schindler G, Capper D, Meyer J, et al. Analysis of BRAF V600E mutation in 1,320 nervous system tumors reveals high mutation frequencies in pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, ganglioglioma and extra-cerebellar pilocytic astrocytoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:397–405. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0802-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balss J, Meyer J, Mueller W, et al. Analysis of the IDH1 codon 132 mutation in brain tumors. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116:597–602. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0455-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ichimura k, Pearson DM, Kocialkowski S, et al. IDH1 mutations are present in the majority of common adult gliomas but rare in primary glioblastomas. Neuro Oncol. 2009;11(4):341–347. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2009-025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capper D, Weissert S, Balss J, et al. Characterization of R132H mutation-specific IDH1 antibody binding in brain tumors. Brain Pathol. 2010;20:245–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2009.00352.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kepes JJ, Rubinstein LJ, Eng LF. Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma: a distinctive meningocerebral glioma of young subjects with relatively favorable prognosis. A study of 12 cases. Cancer. 1979;44:1839–1852. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197911)44:5<1839::aid-cncr2820440543>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kepes JJ, Rubinstein LJ, Ansbacher L, et al. Histopathological features of recurrent pleomorphic xanthoastrocytomas: further corroboration of the glial nature of this neoplasm. A study of 3 cases. Acta Neuropathol. 1989;78:585–593. doi: 10.1007/BF00691285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giannini C, Scheithauer BW, Burger PC, et al. Pleomorphic Xanthoastrocytoma. Cancer. 1999;85:2033–2045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giannini C, Paulus W, Louis DN, Liberski P. Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma. In: Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. 3rd edn. IARC: Lyon; 2007. pp. 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacKenzie JM. Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma in a 62-year-old male. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1987;13:481–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1987.tb00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marton E, Feletti A, Orvieto E, et al. Malignant progression in pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma: personal experience and review of the literature. J Neurol Sci. 2007;252:144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kros JM, Vecht CJ, Stefanko SZ. The pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma and its differential diagnosis: A study of five cases. Hum Pathol. 1991;22:1128–1135. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(91)90265-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chakrabarty A, Mitchell P, Bridges LR, et al. Malignant transformation in pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma--a report of two cases. Br J Neurosurg. 1999;13:516–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu Y-J, Miyahara H, Uzuka T, et al. Intraventricular pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma with anaplastic features. Neuropathol. 2010;30:443–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2009.01080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ng WH, Lim T, Yeo TT. Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma in elderly patients may portend a poor prognosis. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15:476–478. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prayson RA, Morris HH., 3rd Anaplastic pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1998;122:1082–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirose T, Ishizawa K, Sugiyama K, et al. Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma: a comparative pathological study between conventional and anaplastic types. Histopathology. 2008;52:183–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sugita Y, Shigemori M, Okamoto K, et al. Clinicopathological study of pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma: correlation between histological features and prognosis. Pathol Int. 2000;50:703–708. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2000.01104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan T-C, Ho L-C, Yu C-P, et al. Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma: report of two cases and review of the prognostic factors. J Clin Neurosci. 2004;11:203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2003.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tekkök IH, Sav A. Anaplastic pleomorphic xanthoastrocytomas. Review of the literature with reference to malignancy potential. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2004;40:171–181. doi: 10.1159/000081935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okazaki T, Kageji T, Matsuzaki K, et al. Primary anaplastic pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma with widespread neuroaxis dissemination at diagnosis--a pediatric case report and review of the literature. J Neurooncol. 2009;94:431–437. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-9876-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vu TM, Liubinas SV, Gonzales M, et al. Malignant potential of pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2012;19:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korshunov A, Golanov A. Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytomas: immunohistochemistry, grading and clinico-pathologic correlations. An analysis of 34 cases from a single Institute. J Neurooncol. 2001;52:63–72. doi: 10.1023/a:1010648006319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macaulay RJ, Jay V, Hoffman HJ, et al. Increased mitotic activity as a negative prognostic indicator in pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1993;79:761–768. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.79.5.0761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pahapill PA, Ramsay DA, Del Maestro RF. Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma: case report and analysis of the literature concerning the efficacy of resection and the significance of necrosis. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:822–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kleihues P, Burger PC, Aldape KD, et al. Glioblastoma. In: Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. Albany, New York: WHO Publications Center; 2007. pp. 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martinez-Diaz H, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Powell SZ, et al. Giant cell glioblastoma and pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma show different immunohistochemical profiles for neuronal antigens and p53 but share reactivity for class III beta-tubulin. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:1187–1191. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-1187-GCGAPX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watanabe K, Sato K, Biernat W, et al. Incidence and timing of p53 mutations during astrocytoma progression in patients with multiple biopsies. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:523–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenblum MK, Erlandson RA, Budzilovich GN. The lipid-rich epithelioid glioblastoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:925–934. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199110000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fuller GN, Goodman JC, Vogel H, et al. Epithelioid glioblastoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1998;57:501. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akimoto J, Namatame H, Haraoka J, et al. Epithelioid glioblastoma: a case report. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2006;22:21–27. doi: 10.1007/s10014-005-0173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodriguez FJ, Scheithauer BW, Giannini C, et al. Epithelial and pseudoepithelial differentiation in glioblastoma and gliosarcoma: a comparative morphologic and molecular genetic study. Cancer. 2008;113:2779–2789. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gasco J, Franklin B, Fuller GN, et al. Multifocal epithelioid glioblastoma mimicking cerebral metastasis: case report. Neurocirugia (Astur) 2009;20:550–554. doi: 10.1016/s1130-1473(09)70133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Alassiri AH, Birks DK, et al. Epithelioid versus rhabdoid glioblastomas are distinguished by monosomy 22 and immunohistochemical expression of INI-1 but not Claudin 6. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:341–354. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181ce107b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanaka S, Nakada M, Hayashi Y, et al. Epithelioid glioblastoma changed to typical glioblastoma: the methylation status of MGMT promoter and 5-ALA fluorescence. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2011;28:59–64. doi: 10.1007/s10014-010-0009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaulich K, Blaschke B, Nümann A, et al. Genetic alterations commonly found in diffusely infiltrating cerebral gliomas are rare or absent in pleomorphic xanthoastrocytomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61:1091–1099. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.12.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menzies AM, Haydu LE, Visintin L, et al. Distinguishing Clinicopathologic Features of Patients with V600E and V600K BRAF-Mutant Metastatic Melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:3242–3249. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved Survival with Vemurafenib in Melanoma with BRAF V600E Mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sosman JA, Kim KB, Schuchter L, et al. Survival in BRAF V600-mutant advanced melanoma treated with vemurafenib. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:707–714. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nicolaides TP, Li H, Solomon DA, et al. Targeted therapy for BRAFV600E malignant astrocytoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:7595–7604. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]