Abstract

Background:

General satisfaction is a personal experience and sources of satisfaction or dissatisfaction vary between professional groups. General satisfaction is usually related with work settings, work performance and mental health status.

Aim:

The purpose of this research study was to investigate the level of general satisfaction of health care workers and to examine whether there were any differences among employees of medical and mental health sector.

Methods:

The sample consisted of employees from the medical and mental health sector, who were all randomly selected. A two-part questionnaire was used to collect data. The first section involved demographic information and the second part was a General Satisfaction Questionnaire (GSQ). The statistical analysis of data was performed using the software package 19.0 for Windows. Descriptive statistics were initially generated for sample characteristics. All data exhibited normal distributions and thus the parametric t-test was used to compare mean scores between the two health sectors. P values < 0.05 were defined as reflecting the acceptable level of statistical significance.

Results:

457 healthcare workers completed the questionnaire. The mean age of the sample was 41.8 ± 7.9 years. The Cronbach alpha coefficient for GSQ was 0.79. The total mean score of general satisfaction for the employees in medical sector was 4.5 (5=very satisfied) and for the employees in mental health sector is 4.8. T-test showed that these results are statistical different (t=4.55, p<0.01) and therefore the two groups of healthcare workers feel different general satisfaction.

Conclusions:

Mental health employees appear to experience higher levels of general satisfaction and mainly they experience higher satisfaction from family roles, life and sexual life, emotional state and relations with patients.

Keywords: General satisfaction, job satisfaction, life satisfaction, healthcare professionals, mental healthcare workers, medical healthcare workers

1. INTRODUCTION

A considerable number of studies have shown that there is a significant relation between levels of general employee satisfaction and job satisfaction (1-4). General satisfaction is also related with work performance and mental health status (5-7). Statistically strong correlations were also found between general satisfaction and burnout, depression and anxiety (8, 9). The relations that found suggest that the level of general satisfaction is an important factor influencing health status of workers (2, 10).

The factor that influences a lot the level of general satisfaction is job satisfaction (11-14). Job satisfaction is defined as “the balance between factors of working stressors and rewards” (15). Job satisfaction has been also described as: “A pleasurable or positive emotional state which is the result of someone’s working assessment or someone’s working experience. Job satisfaction results from the perception that job fulfills or allows the fulfillment of important values, given that these values are in accordance with individual needs” (1). General satisfaction is actually a personal experience and sources of satisfaction or dissatisfaction vary between professional groups (16-18). Factors that may affect satisfaction among workers are emotional state, business policy, way of administration, supervision, salary, interpersonal relations and working conditions (19, 20).

Burnand and his colleagues, describe a great number of studies which had shown that job satisfaction is associated with employee performance, in health sector is higher in men than in women, is highly influenced by payment, is highly influenced by the duo payment and working autonomy, is correlated negatively with the development prospects of the staff, is reduced when adverse psychological situations are inducing due to poor employee relations, is higher when employees are taking part in decision making and it is correlated with the general culture and the administrative climate in working setting (21).

Fletcher investigated not only nurses’ general satisfaction but also their dissatisfaction (22). In his study 5.192 questionnaires were mailed to registered nurses of which 1.780 were returned completed. The researcher assessed general satisfaction, job satisfaction, patient satisfaction and patient safety, extrinsic values of work, the role of the head master and nurses’ intention to remain in the area of health care. General satisfaction and job satisfaction were evaluated at various levels, which concerned the profit of the nursing unit, the job performance, the intrinsic values of work and patients’ care issues. Results showed that staff is usually possessed by a sense of depreciation of employment and even feels resentful, because it realizes that profit is often placed higher than patients (22). As for the job performance of their colleagues, many declared that they had higher expectations and are being disappointed. At the same time, they expressed concern that patient’s care is not at the level that it should be, mainly due to reduced staffing and due to assignment of multiple tasks to nurses. Also dissatisfaction appeared to staff because of the large number of support staff, which had not the proper training (22). Other research studies showed that higher levels of satisfaction are protective function against burnout (23-25).

Usha Rout conducted a research in which were explored the sources of stress that associated with higher levels of dissatisfaction in workplace and with lower levels of mental health status among physicians (26). The results of this study showed that the main sources of dissatisfaction and lack of mental health were the lack of communication and cooperation between colleagues and staff. The main finding of this study was the fact that it has demonstrated the sources of work stress that are common to all working groups (26). These can be divided into the following different factors; working environment and communication, work and family conflicts and social life, management and success of objectives, problems with patients, requirements due to diseases and economic requirements (26).

In another, rather quite original research, satisfaction that nurses are feeling in their lives was linked with job satisfaction and burnout (27). The survey was conducted on 194 nurses who worked in hospitals with more than 300 beds in Korea. The findings were rather the expected. Nurses that have low job satisfaction and higher levels of burnout also have moderate levels of satisfaction for life in general. The staff that reported higher levels of satisfaction for life had the following characteristics: experiencing high levels of personal achievement and low emotional exhaustion, not working at night and felt happy with the professional status (27).

The purpose of this research study was to investigate the level of general satisfaction of health care workers and to examine whether there were any differences among employees of medical and mental health sector.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

The sample consisted of 240 workers from the medical health sector and 217 from the mental health sector, who were all randomly selected; their mean age was 41.8 ± 7.9 years old. Health workers from University and General Hospitals from all over Greece participated in the study. Randomly selected hospitals from the capital city of every municipality in Greece were included in the study. Mental health sectors as well as medical sectors of the same hospital were included. Local ethical committees approved the study protocol. Doctors, nurses and other healthcare workers (midwives, social workers) participated in the study. The response rate was 76% (457 out of 600 questionnaires), completed without any missing data and thus suitable for final evaluation.

A two-part questionnaire was used to collect data. The first section involved demographic information and the second part was a General Satisfaction Questionnaire (GSQ), which was conducted according to the literature data and used to evaluate health professionals’ general satisfaction [28-31]. The questionnaire has been expanded to contains 13 questions: the satisfaction from life, the satisfaction from emotional state, the satisfaction from relations with others, the job satisfaction, the satisfaction from sexual life, the satisfaction from working environment, the satisfaction from relations with colleagues, the satisfaction from relations with patients, the satisfaction from financial status, the satisfaction from working conditions, the satisfaction from the family role, the satisfaction from health status and the satisfaction from leisure time. The score for each answer was from 1(=not at all satisfied) to 6(=to much satisfied). The processing and statistical analysis of data was performed using the software package 19.0 for Windows. Descriptive statistics were initially generated for sample characteristics. Normality was checked by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. All data exhibited normal distributions and thus the parametric t-test was used to compare mean scores between the two health sectors. P values < 0.05 were defined as reflecting the acceptable level of statistical significance.

3. RESULTS

Demographic data

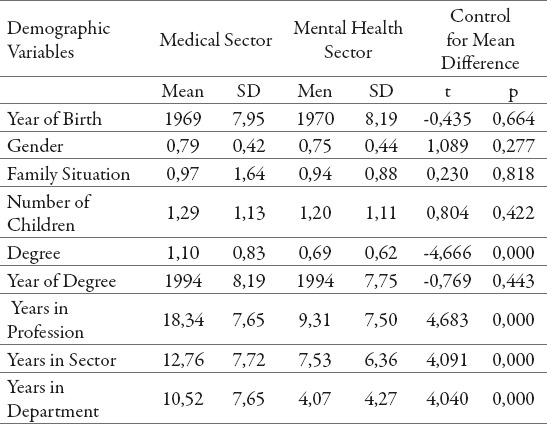

The main measures of demographic data and the statistical t-test between the two groups are presented in Table 1. The mean score of age is almost the same in both groups; just under 42 years. 50% of the employees are below 41 years in mental health sector and over 42 years in medical sector. Mode in both groups is close to 44 (medical sector) and 45 years (mental health sector). Regarding the gender, men are the 25,5% of the workers in mental health sector, and this number is reduced to 21.5% of the employees in medical sector.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistical Results and t-test for Demographic Features of the Sample

The results concerning marital status showed that on average the respondents are married (married=1) with one child. In the medical sector 64.4% declared married, while the proportion in the other sector amounts to 60.2%. The 33.8% of married in medical sector declared that has no children, and in mental health sector this percentage is 38.9%.

The mean score for the educational level takes the value 1.10 (bachelor=1) in medical sector and the value is 0.69 for the mental health sector. In medical field most of the employees (74%) has a bachelor, while this percentage is significantly less (47.5%) in the field of mental health, where a percentage of 46.3% are from secondary education. The difference between the two groups in the level of education is confirmed by the value of t-test (t = 4,666, p= 0.00). For the year in which employees have acquired the most recent qualification results are the same in both groups (1994).

Regarding specialization the two groups differ. In medical sector 80.3% is nursing staff, 10% physicians and 2.1% midwives, while in mental health sector 63.2% is nursing staff, 14.2% physicians and 15.1% declared another specialty.

Working experience of the employees in medical sector is almost twice from working experience of the employees in mental health sector. T-test showed that there is a statistical significance in working experience between the two groups of employees and statistical significance was found in all three variables about experience, years in profession, years in sector and years in department (Table 1).

General Satisfaction Data

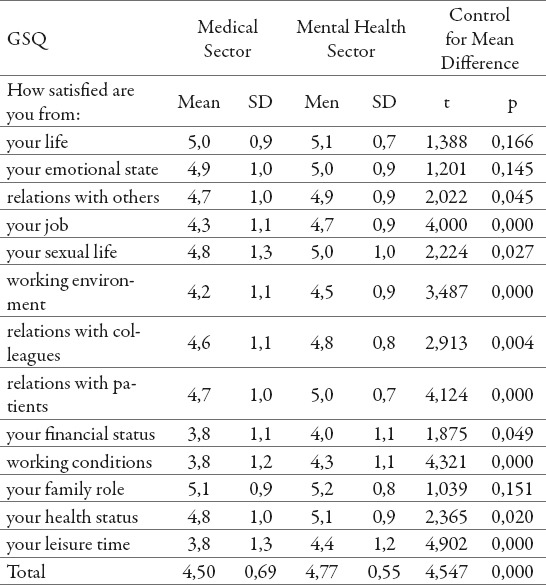

The reliability of GSQ was determined by assessing the Cronbach alpha (internal consistency evaluation of data). The Cronbach alpha coefficient for GSQ was 0.79.

The results about general satisfaction of health care workers and the scores of each variable are presented in table 2. Most of the employees have declared that are slightly (level 4) or very (level 5) satisfied. The total mean score of general satisfaction for the employees in medical sector is 4.5 (5=very satisfied) and for the employees in mental health sector is 4.8. T-test showed that these results are statistical different (t=4.55, p<0.01) and therefore the two groups of healthcare workers feel different general satisfaction.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistical Results and t-test for General Satisfaction of Healthcare Workers

In medical sector the mean scores that are approach level 4 (slightly satisfied) are related with the satisfaction from working conditions (3.8), the satisfaction from leisure time (3.8) and the satisfaction from finances (3.8). The highest scores for this group of employees are appearing in satisfaction from family role (5.1), in satisfaction from life (5.0) and in satisfaction from emotional state (4.9). Quite low can be considered the mean score (4.2) that associated with employees’ satisfaction from their work environment.

In mental health sector is observed approximately the same pattern but the averages are higher. Thus the lower scores of satisfaction of this group of employees are related with the satisfaction from finances (4.0), the satisfaction from working conditions (4.3), the satisfaction from leisure time (4.4) and the satisfaction from their work environment (4.5). The highest scores for mental health care workers are also appearing in satisfaction from family role (5.2), in satisfaction from life (5.1) and in satisfaction from health status (5.1).

The results from t-test showed that except satisfaction from life, satisfaction from emotional state and satisfaction from family role, all the other mean scores are statistically different (p< 0.05) in two groups (Table 2).

4. DISCUSSION

The interesting finding of the study is that there is a significant difference in total scores and in most of the variables of general satisfaction between the two groups of health care employees. Given the fact that the mean scores of GSQ are higher in mental health care workers, it seems that working setting in the mental health sector acts more beneficial.

Research studies have shown that the main factors that are related the most with the satisfaction level of health workers are; the relationships with physicians, the feedback from the managers about the results of the provided care, the official and unofficial interaction among nurses, the fees and finally the recognition of the working role (21, 27, 32, 33). In our study similar factors are appeared as important variables for general satisfaction of health employees.

Ray and Marion, in their research study used a grounded theory to discover how hospitals care for their employees, while taking into account the costs and the expenses (34). The research showed that there is a loss of trust among employees for the management when the health unit is driven mainly by economic incentives. The repeated lack of managerial support, the lack of respect for nursing staff, the need for effective communication and for more transparency in the administration and the desire for greater involvement of nurses in decision-making, are the main factors that affect the level of trust and satisfaction (34).

Many research studies have shown that levels of general satisfaction of employees are strongly related with the ability of the organization to empower its’ workers (35-38). In a study in nursing staff (n = 3016), it was found that higher levels of autonomy, control and cooperation are associated with higher levels of trust in management, which then leads to higher satisfaction (36). In another study 2011 nurses were asked to fill out questionnaires that measured the empowerment that offered in the workplace (37). Empowering was correlated with eight indicators that are related to health; among them were the major depression, anxiety, insomnia and burnout (37). Locke and Latham emphasize in the primary role of freedom of thought and choice which the employees should have (38). Concepts such as autonomy and empowerment are helping in maintenance of the internal work motivation and general satisfaction (38). Empowerment includes power, capacity, activate and satisfaction to employees (37). The ability of nursing staff to practice in accordance with professional standards and values is a basic determinant of satisfaction (35). Empowerment approaches in the workplace, such as participatory management and joint management, are innovations for the right direction and create job satisfaction in a large group of workers in the health sector, such as the nursing staff (35, 37). Additionally, when employees are feeling psychologically and structurally empowered the levels of satisfaction are higher and the pressure that they feel is lower (36).

5. CONCLUSIONS

Mental health employees appear to experience higher levels of general satisfaction and mainly they experience higher satisfaction from family roles, life and sexual life, emotional state and relations with patients. A further study about how other aspects of life and how working environment and settings are influence general satisfaction of the employees would be helpful in determining the factors that are correlated the most.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: NONE DECLARED.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tovey EJ, Adams AE. The Changing Nature of Nurses’ Job Satisfaction: An Exploration of Sources of Satisfaction in the 1990s. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1999;30(1):150–158. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ganster DC, Schaubroeck J. Work stress and employee health. Journal of Management. 1991;17(2):235–271. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hazelrigg LE, Hardy MA. Scaling semantic of satisfaction. Social Indicators Research. 2000;49(2):147–180. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang KJ, Chen SH. The comparison and analysis of employee satisfaction improvement in the hot spring and financial industries. African Journal of Business Management. 2010;4(8):1619–1628. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelloway EK, Barling J. Job characteristics, role stress, and mental health. Journal of Occupational Psychology. 1991;64:291–304. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bluen SD, Barling J, Burns W. Predicting sales performance, job satisfaction, and depression by using the achievement strivings and impatience- irritability dimensions of Type-A Behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1990;75(2):212–216. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart W, Barling J. Daily work stress, mood and interpersonal job performance: A mediational model. Work & Stress. 1996;10(4):336–351. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uskun E, Ozturk M, Kisioglu AN, Kirbiyik S. Burnout and job satisfaction amongst staff in Turkish community health services. Primary Care and Community Psychiatry. 2005;10(2):63–69. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolpin J, Burke RJ, Greenglass ER. Is job satisfaction an antecedent or a consequence of psychological burnout? Human Relations. 1991;44:193–209. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van den Berg TI, Alavinia SM, Bredt FJ, Lindeboom D, Elders LAM, Burdorf A. The influence of psychosocial factors at work and life style on health and work ability among professional workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Helath. 2008;81:1029–1036. doi: 10.1007/s00420-007-0296-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolpin J, Burke RJ, Greenglass ER. Is job satisfaction an antecedent or a consequence of psychological burnout? Human Relations. 1991;44:193–209. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barrett C, Myrick F. Job Satisfaction in Preceptorship and Its Effect on the Clinical Performance of the Preceptee. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1998;27(2):364–371. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tabolli S, Ianni A, Renzi C, et al. Job satisfaction, burnout and stress amongst nursing staff: a survey in two hospitals in Rome. G Ital Med Lav Ergon. 2006;28(1):49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Judge TA, Thoresen CJ, Bono JE, Patton GK. The job satisfaction-job performance relationship: a qualitative and quantitative review. Psychol Bull. 2001;127:376–407. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.3.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corey-Lisle P, Tarzian AJ, Cohen MZ, Trinkoff AM. Healthcare Reform: Its Effects on Nurses. Journal of Nursing Administration. 1999;29(3):30–37. doi: 10.1097/00005110-199903000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mechteld RM, Visser Ellen MA, Smets FJ, et al. Stress, satisfaction and burnout among Dutch medical specialists. Canadian Medical Association. 2003;168(3):271–275. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters D, Chakraborty S, Mahapatra P, Steinhardt L. Job satisfaction and motivation of health workers in public and private sectors: cross-sectional analysis from two Indian states. Hum Resour Health. 2010;8(1):27. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-8-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miljkovic S. Motivation of employees and behavior modification in health care organizations. Acta Medica Medianae. 2007;46:53–62. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jamal M, Baba VV. Shiftwork and department-type related to job stress, work attitudes and behavioral intentions: A study of nurses. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1992;13:449–464. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kangas S, Kee CC, McKee-Waddle R. Organisational Factors, Nurses’ Job Satisfaction, and Patient Satisfaction with Nursing Care. Journal of Nursing Administration. 1999;29(1):32–42. doi: 10.1097/00005110-199901000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burnard P, Morrison P, Phillips C. Job satisfaction amongst nurses in an interim secure forensic unit in Wales. Austral and New Zeal J Ment Health Nurs. 1999;8(1):9–18. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0979.1999.00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fletcher CE. Hospital RN’s job satisfactions and dissatisfactions. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2001;31(6):324–331. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200106000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dolan N. The relationship between burnout and job satisfaction in nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1987;12:3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1987.tb01297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, et al. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(16):1987–1993. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krogstad U, Hofoss D, Veenstra M, et al. Predictors of job satisfaction among doctors, nurses and auxiliaries in Norwegian hospitals: relevance for micro unit culture. Human Resources for Health. 2006:4–3. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rout U. Occupation al Stress in women general practitioner and practice managers. Women in Management Review. 1999;14(6):220–230. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee H, Hwang S, Kim J, Daly B. Prediction of Life Satisfaction of Korean Nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2004;48(6):632–641. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aday LA, Cornelius LJ. 3rd Edition. Josey- Bass; 2006. Designing and conducting health surveys: a comprehensive guide. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bovier PA, Perneger TV. Predictors of work satisfaction among physicians. Eur J Public Health. 2003;13:299–305. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/13.4.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faragher EB, Cass M, Coopre CL. The relationship detween job satisfaction and health: a meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2005;62:105–112. doi: 10.1136/oem.2002.006734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conti G, Pudney S. Survey design and the analysis of satisfaction. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2011;93(3):1087–1093. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Currid TJ. The lived experience and meaning of stress in acute mental health nurses. Br J Nurs. 2008;17:880–884. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2008.17.14.30652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jayasuriya R, Whittaker M, Halim G, Matineau T. Rural health workers and their work environment: the role of inter-personal factors on job satisfaction of nurses in rural Papua New Guinea. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):156. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ray M, Marion F. The transformative process for nursing in workforce redevelopment. Nursing Administration Quarterly. 2002;62(2):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laschinger H, Sabiston JA. Staff Nurse Empowerment and Workplace Behaviours. The Canadian Nurse. 2000;96(2):18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laschinger H, Finegan J, Shamian J, Casier S. Organizational trust and empowerment in restructured healthcare settings: Effects on staff nurse commitment. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2000;30(9):413–425. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200009000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hochwälder J, Brucefors AB. Psychological empowerment at the workplace as a predictor of ill health. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;39(7):1237–1248. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Locke EA, Latham GP. What should we do about motivation theory? Six recommendations for the twenty-first century. Academy of Management Review. 2004;29:388–403. [Google Scholar]