Abstract

Background:

Sedentary life style and consequent obesity prevail in both developed and developing nations; gender- and age-independently. Physical inactivity in a population in a life style transition–like Saudi Arabia–causes metabolic syndrome with its immediate and long-term complications. Healthcare workers are in a better position for role modeling and counseling of appropriate health behaviors. Personal physical activity and body built among physicians influences to some degree their exercise counseling. Realizing such principle necessitates gauging the extent of physical activity among physicians and assessing the likelihood of counseling the patients on physical activities.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study enrolled primary health care physicians (PHCPs) from primary health care centers and general hospitals of two cities (Sakaka and Dumat Al-Jandal) of Aljouf region, Saudi Arabia. Both genders were included. English version of step-wise questionnaire of World Health Organization was used for data collection.

Results:

The response rate was 64.2%. 65.2% of respondent PHCPs were doing moderate to vigorous physical exercise and 34.8% of them were physically inactive. Majority of physically inactive PHCPs had intention to increase their physical activity. Neither gender, nationality nor city-wise significant differences were recorded. However, physically active PHCPs significantly impart advice and role modeling on physical activity to their patients compared to physically inactive PHCPs (p<0.01).

Conclusion:

Most PHCPs in Sakaka and Dumat Al-Jandal cities were physically active and were able to impart the healthy behavior counseling to their patients. A strong intention prevailed to increase physical activity among physically inactive Primary Health care Physicians (PHCPs).

Keywords: Primary health care physicians, Physical activity

1. INTRODUCTION

Physical inactivity is recognized as one of the leading risk factor for mortality around the world that leads to an estimated 3.2 million deaths globally (1). Saudi Arabia has undergone a drastic change in life style and eating habits. The burden of life style related diseases such as diabetes, coronary artery diseases and hypertension has increased and these diseases are associated with physical inactivity (2). These diseases have become the principal cause of morbidity and mortality in Saudi Arabia (3). World Health Organization (WHO) estimates the prevalence of physical inactivity among Saudi children, youth and adults are 57%, 71% and 80%, respectively (4).

WHO stresses that promotion of physical activity should be an important public health objective (5,6). Healthcare workers are in a better position for counseling of appropriate health behaviors including physical activity. Personal physical activity among physicians and its reflection on their body built influence to some degree their exercise counseling (7). Organizations now train their healthcare providers to advice patients about the needs of physical activity. For instance, the American Heart Association (AHA) assesses physical activity at every routine evaluation for primary prevention of stroke and cardiovascular diseases (8, 9).

The single most common cause of obesity in developed countries is physical inactivity, rather than amount and nature of food intake or other factors. Obesity has been estimated to affect 20 to 40 percent of the adults and 10 to 20 percent of children and adolescents in developing countries (10). The first adverse effects of obesity to emerge in a population in a socioeconomic transition state are hypertension, hyperlipidemia and glucose intolerance, while coronary heart disease and the long term complications of diabetes, such as renal failure begin to emerge several years (or decades) later (11).

A prevailing physical activity practice among healthcare providers would help them role modeling and promoting physical activity among their patients. Knowing the extent of such activity would help setting measures that ensure its promotion. There are no previous studies on the extent of physical activity among healthcare providers in Aljouf area, as aimed by the present study. The prevalence of physical activity among primary health care physicians (PHCPs) and the likelihood of imparting counseling services to their patients in Aljouf area, Saudi Arabia were assessed using a WHO stepwise questionnaire.

2. OBJECTIVES

-

■

To determine the prevalence of physical activity among PHCPs in Aljouf region of Saudi Arabia.

-

■

To assess the likelihood of counseling the patients on physical activities.

3. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects: PHCPs of both genders in Sakaka and Dumat Al-Jandal areas of Aljouf region of Saudi Arabia were voluntarily surveyed in this study. A total of 164 physicians of governmental fifteen primary health care centers (PHCs) and two general hospitals in Sakaka and Dumat Al-Jandal were surveyed. Survey was started after approval from the Ethical Committee, College of Medicine, Aljouf University, Sakaka, Saudi Arabia.

3.1. Design

A cross-sectional study.

3.2. Data Collection

Data was collected using English version of WHO stepwise questionnaire. Questionnaire also captured data on age, gender and country of origin of PHCPs. Two questions regarding the physician’s future plan/intention on improving physical activity were added to the questionnaire.

3.3. Exclusion criteria

Physicians on night shifts, physicians on vacation during the study period and physicians working in private sector.

3.4. Exit interview

Before meeting the physicians with the questionnaire, an exit interview of patients regarding advice on physical activity was carried out to prevent the influence of our questionnaire. These interviews were carried out at male outpatient departments before meeting the physician for his data collection. No female patient was interviewed due to cultural barriers.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Data was analyzed using SPSS Version-17. Frequencies on physical activity were calculated. Chi square test was used for comparison of physical activity between groups of physicians (PHC vs. Hospitals and Sakaka vs. Dumat Al-Jandal) and between genders.

4. RESULTS

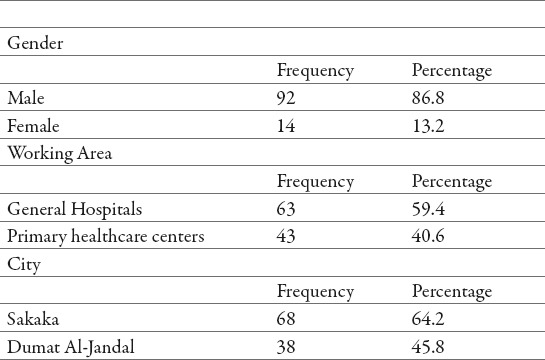

From total amount of 164 physicians of both genders were surveyed in this study. 106 physicians responded to the survey with a response rate of 64%. Subsequent analysis is based on the responses of those 106 physicians. Males comprised 86% of study physicians and 13% physicians were females. Majority of participants (59%) were from hospitals compared to primary healthcare centers (41%). 64% of physicians surveyed belonged to primary health centers situated in Sakaka and 36% were from Dumat Al-Jandal (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and work distribution of primary health care physicians participating in the study surveying the extent of their physical activity in Al-Jouf Region, Saudi Arabia.

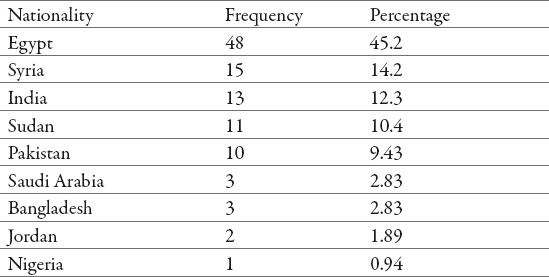

Majority of the physicians working in this area were Egyptians (45%) followed by Syrians (14%) and Indians (12%). Small proportion (3%) of physicians was Saudi nationals (Table 2). The age distribution of the surveyed sample ranged from 27 to 63 years with a median of 45 years.

Table 2.

Nationality distribution of primary health care physicians participating in the study surveying the extent of their physical activity in Al-Jouf Region, Saudi Arabia.

Results of the survey showed that 44.32% of participants were doing moderate physical exercise, 25.35% were doing mild exercise and 20.88% were doing vigorous physical activity. Small proportions of physicians (9.45%) were not doing any exercise or rarely doing any physical activity. Moderate to vigorous physical activities constitute 65.2% of the total number of physicians (Figure 1).

Among the surveyed physicians, prevalence of physical inactivity was 34.8% that included those who are physically inactive and those who do some light activities. Majority of physically inactive physicians (84%) were planning to increase their physical activity in future. 31.13% of physically inactive physicians were very confident and 68.86% were less confident to do so.

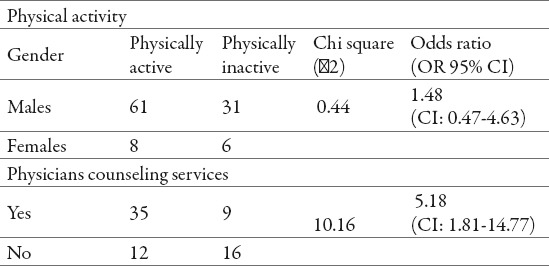

Chi-Square test did not show any significant difference (P>0.05, χ2=0.44,OR=1.48,CI=0.47-4.63) in physical activity between males and females (Table 3), as well as between physicians from the two cities; Sakaka and Dumat Al-Jandal.

Table 3.

Gender-dependent difference in physical activity and counseling services by primary health care physicians participating in the study. (CI=Confidence interval)

Seventy-two (72) patients exist interviews were carried out at male outpatient department before meeting the physician. Physicians who were physically active were more likely to impart advice on physical activity to their patients compared to physically inactive physicians. There was a significant difference (P<0.01,χ2=10.16,OR=5.18,CI=1.81-14.77) between the two groups of physicians in this respect (Table-3).

5. DISCUSSION

The physiological and psychological benefits of exercise are well known and it was encouraging to find in our study that most physicians were actually performing physical exercise. Studies have shown the benefits of regular physical activity in preventing diseases and promoting health (12,13). Benefits of physical activity include the prevention of hypertension, stroke, heart disease, type II diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia and obesity (14-17). Physical activity improves psychological and cognitive function as well (18, 19).

Current study found that physicians who do moderate to vigorous physical activities constitute 65.2% of total number of physicians. We found that only 34.8% of the physicians were inactive. Our study results are comparable to the results of other studies (20,21). Suija et al in their study done on female family doctors found that 92% of them were physically active (25). Recent study on physical therapists in the United States also showed them to be physically more active than the US adult population (26). A study carried out by Gnanendran et al in Australia found that 70% of doctors and medical students satisfying the National Physical Activity Guidelines, which was higher than 30% as seen in the general population (27). Medscape carried a survey in (2012) that showed that physicians are physically more active than the average Americans and their level of activity increases as they grow older (28).

Previous studies showed a contrary pictures in other countries with lower results for physicians being active. A survey carried out by Paul et al found that 30% of surveyed physicians were active (29). Among 616 physicians employed in the Faculty of Medicine at Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt, 84% were sedentary (no or irregular physical activity) (30). In Bahrain, a study conducted in 2003 observed that 29% of physicians were physically active (31). Many other studies in other parts of the world have found the physicians to be less active than the general population (32).

The prevalence of physical inactivity among surveyed doctors in our study was 34.8%, which is lower than general population of Saudi Arabia. WHO estimates that the prevalence of physical inactivity among Saudi children, youth and adults is 57%, 71% and 80% respectively (4).

Our study did not show any significant difference in physical activity among physician’s of the two cities and between genders. Biernat et al in their study on medical professionals also did not observe any difference in physical activity between genders (32).

Physicians with less or no physical activity are less likely to encourage patients to engage in physical activity in geographic areas with less active adult population (33). Physically active healthcare providers are more likely to counsel the patients on physical activity (34-35). Encouraging physical activity among healthcare providers could help change behaviors among the general population (34). Our results confirmed the conclusion of such studies. Our study showed that physically active physicians are significantly imparting counseling on physical activity more often than physically inactive physicians.

Our study showed confidence among inactive physicians to increase their physical activity, which will have a positive impact on the patients in particular and on the community in general. Paul et al also found in their study that physicians believed exercise is of value to their patients and to themselves (29).

6. CONCLUSION

Majority of the physicians surveyed in the current study were physically active, however, among inactive population of physicians, 84% were planning to increase their physical activity and 31.13% of them were very confident of doing so.

Physicians who were physically active were significantly more likely to impart advice on physical activity to their patients compared to physically inactive physicians.

7. RECOMMENDATION

Saudi Arabia is facing huge burden of lifestyle diseases, which is going to rise in future. An increase in physical activity among general population is essential to keep a check on this rise. A program that encourages and felicitates physical activity among physicians with incentives would bring a significant difference in their ability to counsel and set role modeling for physical activity among their patients.

Limitation

The study did not include the effect on counseling services on patient’s actual change in behavior. Further studies are warranted to see the effect of counseling services on patient behavior outcome.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgement

Authors are thankful to the Director General Health Aljouf region for giving us permission to carry out the study and also thank all the physicians for their cooperation. Authors also thank Professor Tarek H. El-Metwally of Medical Biochemistry, College of Medicine, Aljouf University for reviewing the final script of the paper.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: NONE DECLARED

REFERENCES

- 1.Mikhail T. Physical activity. 2007. Available http://www.who. int /topics / physical _activity /en/

- 2.Midhet F, Al Mohaimeed AR, Sharaf F. Dietary practices, physical activity and health education in Qassim region of Saudi Arabia. International J. Health Sciences. 2010;4:3–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chopra M, Galbraith S, Darnton-Hill I. 12. Vol. 80. Geneva: 2002. Introduction to PHC Bulletin of World Health Organization, 2002. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Hazzaa H. The public health burden of physical inactivity in Saudi Arabia. J. Family & Community Medicine. 2004;11:45–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. The world health report 2002. Reducing risks, promoting healthy life. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Geneva: 2004. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lobelo F, Duperly J, Frank E. Physical activity habits of physicians and medical students influence their counseling practices. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:89–92. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.055426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pearson TA, Blair SN, Daniels SR, Eckel RH, Fair JM, Fortmann SP, Franklin BA, Goldstein LB, Greenland P, Grundy SM, Hong Y, Miller NH, Lauer RM, Ockene IS, Sacco RL, Sallis JF, Jr, Smith SC, Jr, Stone NJ, Taubert KA. AHA. Guidelines for Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke: 2002 Update: Consensus Panel Guide to Comprehensive Risk Reduction for Adult Patients Without Coronary or Other Atherosclerotic Vascular Diseases. American Heart Association Science Advisory and Coordinating Committee. Circulation. 106:388–391. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000020190.45892.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vanhees L, Levefre J, Philippaerts R, Martensa M, Huygens W, Troosters T, Beunen G. “How to assess physical activity? How to assess physical fitness?”. Eur J of Cardiovas Prev& Rehab. 2005;12:102–114. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000161551.73095.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, Powell KE, Blair SN, Franklin BA, Macera CA, Heath GW, Thompson PD, Bauman A. “Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association.”. Circulation. 2007;116(9):1081–1093. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NIH Consensus Development Panel on Physical Activity and Cardiovascular Health. Physical activity and cardiovascular health. JAMA. 1996;276(3):241–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN, Haskell WL, Macera CA, Bouchard C, Buchner D, Ettinger W, Heath GW, King AC, Kriska A, Leon AS, Marcus BH, Morris J, Paffenbarger RS, Patrick K, Pollock ML, Rippe JM, Sallis J, Wilmore JH. Physical activity and public health. A recommendation from the centres for disease control and prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. JAMA. 1995;273:402–407. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO (1995) Technical Report series. NO:854 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tashev T. Food and nutrition bulletin. 3. Vol. 8. The United Nations University Press, 1986; 1986. Nutritional aspects of obesity and diabetes and their relation to cardio-vascular. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee IM, Sesso HD, Oguma Y, Paffenbarger RS., Jr Relative intensity of physical activity and risk of coronary heart disease. Circulation. 2003;107(8):1110–1116. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000052626.63602.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee CD, Folsom AR, Blair SN. Physical activity and stroke risk: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2003;34:2475–2481. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000091843.02517.9D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whelton SP, Chin A, Xin X, He J. Effect of aerobic exercise on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:493–503. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-7-200204020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, La-chin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berman DM, Rogus EM, Busby-Whitehead MJ, Katzel LI, Goldberg AP. Predictors of adipose tissue lipoprotein lipase in middle-age and older men: relationship to leptin and obesity, but not cardiovascular fitness. Metabolism. 1999;48:183–189. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(99)90031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donnelly JE, Hill JO, Jacobsen DJ, Potteiger J, Sullivan DK, Johnson SL, Heelan K, Hise M, Fennessey PV, Sonko B, Sharp T, Jakicic JM, Blair SN, Tran ZV, Mayo M, Gibson C, Washburn RA. Effects of 16-month randomized controlled exercise trial on body weight and composition in young, overweight men and women: the Midwest Exercise Trial. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1343–1350. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.11.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greist JH. Exercise intervention with depressed outpatients. In: Morgan WP, Goldston SE, editors. Exercise and mental health. Washington: Hemisphere; 1987. pp. 117–121. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnes DE, Yaffe K, Satariano WA, Tager IB. A longitudinal study of cardio respiratory fitness and cognitive function in healthy older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:459–465. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brotons C, Bjfrkelund C, Bulc M, Ciurana R, Godycki-Cwirko M, Jurgova E, Kloppe P, Lionis C, Mierzecki A, Pineiro R, Pullerits L, Sammut MR, Sheehan M, Tataradze R, Thireos EA, Vuchak J. Prevention andhealth promotion in clinical practice: the views of general practitioners in Europe. Preventive Medicine. 2005;40:595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frank E, Segura C. Health practices of Canadian physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:810–811. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suija K, Pechter U, Maaroos J, Kalda R, Ratsep A, Oona M, Ma-roos HI. Physical activity of Estonian family doctors and their counselling for a healthy lifestyle: a cross-sectional study. BMC Family Practice. 2010;11:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chevan J, Haskovitz EM. Do as I do: exercise habits of physical therapists, physical therapist assistants, and student physical therapists. Physical Therapy. 2010;90:76–94. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20090112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gnanendran A, Pyne DB, Fallon KE, Fricker PA. Attitudes of medical students, clinicians and sports scientists towards exercise counselling. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine. 2011;10:426–431. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Medscape Physician lifestyle report: 2012 results. :12. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaertner PH, Firor WB, Edouard L. Physical inactivity among physicians. Can Med Assoc J. 1991;144:1253–1256. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rady M, Sabbour SM. Behavioral risk factors among physicians working at Faculty of Medicine – Ain Shams University. J Egypt Health Assoc. 1997;72:233–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bahram S, Abbas B, Kamal J, Fakhro E. Leisure-time physical activity habits among physicians. Bahrain Med Bull. 2003;25:80–82. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biernat E, Poznanska A, Gajewski AK. Is physical activity of medical personnel a role model for their patients? Ann Agric Environ Med. 2012;19:707–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stanford FC, Durkin MW, Stallworth JR, Blair SN. Comparison of physical activity levels in physicians and medical students with the general adult population of the United States. Phys Sportsmed. 2013;41:86–92. doi: 10.3810/psm.2013.11.2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Physically active healthcare providers more likely to give physical activity counseling. American Heart Association Meeting Report. 2013 Mar 22; [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garcia de Quevedo I, Lobelo F. EPINPAM 2013. New Orleans, LA: 2013. Mar 21, Healthcare providers as role models for physical activity; p. 420. Abstract. [Google Scholar]