Abstract

Purpose

To determine the possibility of obtaining high-quality magnetic resonance (MR) images before, during, and immediately after ejaculation and detecting measurable changes in quantitative MR imaging parameters after ejaculation.

Materials and Methods

In this prospective, institutional review board–approved, HIPAA-compliant study, eight young healthy volunteers (median age, 22.5 years), after providing informed consent, underwent MR imaging while masturbating to the point of ejaculation. A 1.5-T MR imaging unit was used, with an eight-channel surface coil and a dynamic single-shot fast spin-echo sequence. In addition, a quantitative MR imaging protocol that allowed calculation of T1, T2, and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values was applied before and after ejaculation. Volumes of the prostate and seminal vesicles (SV) were calculated by using whole-volume segmentation on T2-weighted images, both before and after ejaculation. Pre- and postejaculation changes in quantitative MR parameters and measured volumes were evaluated by using the Wilcoxon signed rank test with Bonferroni adjustment.

Results

There was no significant change in prostate volumes on pre- and postejaculation images, while the SV contracted by 41% on average (median, 44.5%; P = .004). No changes before and after ejaculation were observed in T1 values or in T2 and ADC values in the central gland, while T2 and ADC values were significantly reduced in the peripheral zone by 12% and 14%, respectively (median, 13% and 14.5%, respectively; P = .004).

Conclusion

Successful dynamic MR imaging of ejaculation events and the ability to visualize internal sphincter closure, passage of ejaculate, and significant changes in SV volumes were demonstrated. Significant changes in peripheral zone T2 and ADC values were observed.

Ejaculatory disorders, such as retrograde ejaculation, ejaculatory duct obstruction, or anejaculation, are important contributors to male infertility (1–3). They can arise as primary disorders or can be secondary to treatment of another disease. For example, treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia—such as silodosin (4,5) or transurethral prostate resection (6–8)—prostate ablation, and radiation treatment for prostate cancer (9–12) frequently causes ejaculation problems. In addition, primary ejaculation disorders are not infrequent, with reduced volume of ejaculate affecting one in two patients and ejaculatory pain affecting one in 10 men over the age of 40 (13).

On the other hand, studies of ejaculation–especially imaging studies–have been scarce, with no magnetic resonance (MR) imaging studies reported to date. The lack of MR imaging studies of ejaculation is especially conspicuous. Multiparametric prostate MR imaging is used extensively for staging of prostate cancer detected at biopsy and for biopsy and treatment guidance (14–16). The detection and characterization of cancerous lesions at MR imaging are important. Most cancerous lesions are detected in the peripheral zone (PZ) on the basis of T2-weighted and diffusion-weighted MR imaging (14–18), and it would be important to establish whether ejaculation affects lesion conspicuity and contrast.

An ultrasonographic (US) study documented that ejaculation can affect imaging results, showing that ejaculation increases blood flow to the prostate for at least 24 hours, which affected the clinical assessment of prostatitis (19). Similarly, ejaculation could effect changes in T2 and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values in the prostate or in the T2- or ADC-based contrast between normal and cancerous tissue. For example, the use of quantitative MR imaging parameters such as ADC is currently hampered by relatively high interpatient variability (17). It is not known whether the ejaculatory state (ie, when the most recent ejaculation occurred) contributes to this interpatient variability. It has been postulated that the ejaculatory state could change the conspicuity of prostate cancer, but an evidence base is lacking.

The aim of this pilot study was to establish whether real-time MR imaging of the prostate before, during, and after ejaculation is feasible and meaningful. We tested the hypotheses that (a) it is possible to obtain quality MR images before, during, and immediately after ejaculation and (b) there are measurable changes in quantitative MR imaging parameters after ejaculation.

Materials and Methods

Volunteer Recruitment and Study Methods

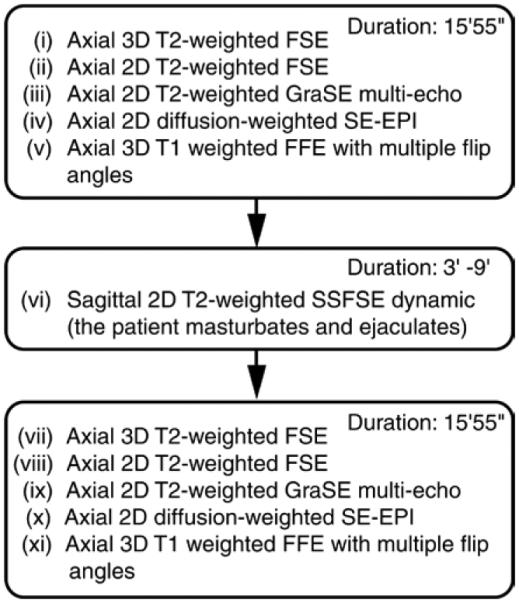

In this prospective study, eight healthy young male volunteers (mean age, 23 years; median, 22.5 years; range, 20–28 years) were recruited through on-campus advertisement, in accordance with an institutional review board–approved protocol, between December 2012 and April 2013. Informed consent was obtained after the nature of the procedures of this Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant study had been explained in detail. The participants were asked to abstain from ejaculation for at least 3 days prior to the experiment. Window blinds were used as a visual barrier between the MR imaging operator and the MR unit, so the subjects were isolated for privacy. The flowchart in Figure 1 illustrates the order of pulse sequences and duration of the MR imaging protocol. The subjects were positioned supine in the MR imager and were instructed to lie still while their pelvis was being imaged before ejaculation (pulse sequences i–v, Fig 1). At the midpoint of the imaging protocol (during pulse sequence vi), the subjects were instructed to begin masturbating until ejaculation occurred, while their prostate and seminal vesicles (SV) were imaged dynamically (pulse sequence vi). Dynamic imaging was performed with 6-second temporal resolution until 1–2 minutes after subjects pressed a signaling button to indicate that ejaculation had occurred. The subjects were instructed to minimize the motion of their pelvis during masturbation. The subjects continued to lie still for the remainder of the examination after ejaculation (pulse sequences vii–xi).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the MR protocol illustrates order of MR sequences and duration of the protocol. FFE = fast field echo, FSE = fast spin echo, GraSE = gradient and spin echo, SE-EPI = spin-echo echo-planar imaging, SSFSE = single-shot fast spin echo, 3D = three-dimensional, 2D = two-dimensional.

MR Imaging Protocol

A 1.5-T Achieva MR imaging unit (Philips, Best, the Netherlands) and an eight-channel surface coil were used for imaging. The pulse sequences and parameters used in our quantitative prostate MR imaging protocol are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pulse Sequences and Relevant Parameters Used in the MR Protocol

| Sequence | Field of View (mm) |

Resolution (mm) | Section Thickness (mm) |

No. of Sections Acquired |

Repetition Time (msec) |

Echo Time (msec) |

Echo Train Length* |

Flip Angle (degrees) |

b Values (sec/mm2) |

Temporal Resolution (sec) |

Sequence Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre- and postejaculation anatomic imaging | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Axial 3D T2-weighted fast spin echo | 200 | 1 | 1 | 150 | 2000 | 200 | 94 | 90 | … | … | 2 min 32 sec |

|

| |||||||||||

| Axial 2D T2-weighted fast spin echo | 180 | 0.8 | 5 | 25 | 3500 | 90 | 24 | 90 | … | … | 3 min 23 sec |

|

| |||||||||||

| Quantitative imaging | … | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Axial 2D T2-weighted gradient and spin-echo multiecho |

230 × 182 | 1.5 | 5 | 25 | 3268 | 20, 40, 60, 80, 100 |

5/5 | 90 | … | … | 2 min 47 sec |

|

| |||||||||||

| Axial 2D diffusion-weighted spin-echo echo-planar imaging |

260 | 2 | 5 | 25 | 4025 | 75 | 129 | 90 | 0, 50, 200, 500, 800 |

… | 2 min 37 sec |

|

| |||||||||||

| Axial 3D T1-weighted fast field echo | 380 × 356 | 2 | 5 | 25 | 12 | 2.85 | 10, 20 | … | … | 2 min 18 sec for each flip angle |

|

|

| |||||||||||

| Dynamic imaging | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Sagittal 2D T2-weighted single-shot fast spin echo |

360 | 1.5 | 6 | 12 | 2000 | 80 | 80 | 90 | … | 6.0 | 3 min to 9 min |

For fast spin-echo and echo-planar imaging sequences.

Qualitative MR Imaging Analysis

Images were evaluated by a board-certified radiologist (A.O.) with 13 years of experience in interpreting prostate MR images, by using iSite PACS Client (Philips Healthcare, Andover, Mass). Pre- and postejaculation T2-weighted and ADC images were compared visually. Changes were noted in prostate and SV size, as well as in signal intensity in the peripheral zone (PZ) and central gland (CG). The prostate and SV and other reproductive organs were segmented by A.O. on 2D and 3D images from T2-weighted sequences by using ITK-SNAP 2.2 software (open source, www.itksnap.org) on a Windows XP Professional (Microsoft, Redmond, Wash) workstation. Prostate and SV volumes were calculated by summing all the segmented volumes in all sections where they were visible. The diameters of the vas deferens and the ejaculatory duct were measured before and after ejaculation on T2-weighted images. Real-time images were evaluated by A.O. qualitatively for the presence, absence, and timing of contraction of the internal and external urinary sphincters, contractions of the prostate and SV, and presence of ejaculate in the urethra. The timing was calculated relative to the dynamic image identified by the subject by pressing a signaling button at the onset of ejaculation.

Quantitative MR Imaging Analysis

Three quantitative MR imaging parameters were calculated in the prostate: T1 (over the whole prostate), T2 (in the CG and PZ), and ADC (in the CG and PZ). For each of the three regions (whole prostate, CG, and PZ), regions of interest (ROIs) were outlined on a representative section of the corresponding pulse sequence. Thus, five measurements were performed in each patient, before and after ejaculation. For T1 measurement, a dual flip angle method was used by using sequence v, where signal intensity is fit as a function of flip angle, repetition time, and T1 (20–22). T1 value was reported as the mean over the whole prostate ROI on a given section. T2 measurements were conducted by performing a monoexponential fit to the signal intensity in each voxel, as measured over the five echoes in the multiecho T2-weighted pulse sequence (sequence iii). T2 values were reported as means over the CG and PZ ROIs. ADC measurements were conducted by performing a monoexponential fit to the signal intensities in each voxel, as measured over the five b values of the diffusion-weighted pulse sequence (sequence iv). ADC values were reported as means over the CG and PZ ROIs. All ROIs were outlined by using custom-built software written in Interactive Data Language (Exelis VIS, Boulder, Colo), with the supervision of the radiologist (A.O.). The ROI size range was 0.13–1.55 cm3 in the CG, 0.29–2.07 cm3 in the PZ, and 1.50–3.50 cm3 for the whole prostate. The pre- and postejaculation images were not coregistered, but the pre- and postejaculation ROIs were placed in the corresponding regions of the prostate.

Statistical Analysis

The pre- and postejaculation percentage changes in volumes of the prostate and SV and in the values of the five measurements performed in each subject (T1 in the whole prostate and T2 and ADC in CG and PZ) were compared by using a two-sided Wilcoxon signed rank test at the significance level of P = .05, implemented in Interactive Data Language (Exelis VIS). The Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons reduced the a level required to demonstrate significance to P = .007.

Results

Volunteer Population

All volunteers completed the study and were able to ejaculate during the examination, with time intervals ranging from 40 seconds to 7 minutes.

Real-time Imaging

Figure 2 shows representative sagittal sections from the dynamic single-shot fast spin-echo pulse sequence (sequence vi) through the medial plane of two volunteers, showing the prostate and the surrounding structures. Prior to ejaculation (Fig 2, A and C), the pre-prostatic (internal) sphincter is relaxed. During ejaculation (Fig 2, B and D), it is contracted, blocking the urethra. The ejaculate is clearly visualized within the prostate at the time of ejaculation.

Figure 2.

Medial MR sections acquired with the dynamic single-shot fast spin-echo (repetition time [msec]/echo time [msec], 2000/80) pulse sequence in a 23-year-old (top) and a 25-year old (bottom) healthy volunteer. A, C, Before ejaculation, the internal sphincter (arrow) is open. B, D, During ejaculation, the internal sphincter (arrow) is closed, and the ejaculate (arrowhead) is visualized within the prostatic urethra. The images were obtained 24 seconds (B) and 36 seconds (D) after the internal sphincter closed and 30 seconds (B, D) after the subject indicated that ejaculation was occurring.

Typically, the external sphincter was not well visualized, and we did not observe contractions of the prostate and SV with the 6-second time resolution we used. We were able to observe the contraction and relaxation of the internal sphincter in seven of eight subjects, and we measured their timing relative to the ejaculation time as signaled by the subject. In one case, the ejaculation events observed with real-time imaging all occurred after the subject-signaled ejaculation time, indicating that the signaling button was pressed too early, and we excluded this subject from calculations of relative time points. The mean onset of internal sphincter contraction was −12 seconds (negative values denote occurrence prior to signaled ejaculation; median, −9 seconds; range: −36 seconds to 0 seconds), and that of internal sphincter relaxation was +16 seconds (median, 12 seconds; range, 6–30 seconds). The mean duration of internal sphincter contraction was 28 seconds (median, 21 seconds; range, 12–66 seconds). The ejaculate was visualized as a thick, bright line within the prostatic urethra (Fig 2, B and D) in six of eight subjects, appearing at −13 seconds on average (median, −6 seconds; range, −30 to −6 seconds). This timing is similar but not identical to that of internal sphincter contraction (mean time difference, −1 second; median, 0 seconds; range, −6 to 6 seconds).

Qualitative Appearance of Standard MR Images

Figure 3 shows representative T1-weighted, T2-weighted, diffusion-weighted, and ADC images of the same section through the prostate of a volunteer, before and after ejaculation. The qualitative appearance of MR images did not change dramatically after ejaculation. Two volunteers were found to have utricle cysts.

Figure 3.

Representative axial sections of the prostate in a 23-year-old healthy volunteer before (left) and after (right) ejaculation. A, B, T1-weighted (12/2.85; flip angle, 10°), C, D, T2-weighted (3500/90), E, F, diffusion-weighted (4025/75; b = 800 sec/mm2), and G, H, ADC (4025/75; b = 0, 50, 200, 500, and 800 sec/mm2) images. No dramatic change can be observed qualitatively between pre- and postejaculation images, although quantitative changes in T1, T2, and ADC ranged from −16% (ADC in the CG) to +9% (T2 in the CG for this patient). The field of view differs for each pulse sequence, but the same axial location is shown.

In a side-by-side comparison of T2-weighted pre- and postejaculation images, the PZ showed reduced size and signal intensity after ejaculation in seven of eight subjects (the remaining subject showed no change). The CG showed no changes in size or signal intensity, except for in one subject, who showed reduced signal intensity without a size change. The SV appeared smaller after ejaculation on T2-weighted images in six subjects and unchanged in two. In side-by-side comparison of ADC on pre- and postejaculation images, the CG and PZ showed no changes in either size or signal intensity, except that in two subjects, a reduced PZ signal intensity was observed.

Volume and Diameter Measurements

T2-weighted 2D images allowed easier prostate and SV segmentation than did the 3D sequence, owing to improved contrast and better delineation. Figure 4 shows a representative section of the SV in a 22-year-old healthy volunteer, before and after ejaculation. The median and range values for prostate and SV volume measurements are displayed in Table 2. We list the pre- and postejaculation volumes, the difference and percentage difference, and the P value for the comparisons. In our population, there was no observed reduction in prostate volume, but we observed a significant reduction in SV volume. The median ejection fraction in the SV was 44.5% (range, 14%–65%), with the median decrease in volume of 5.6 cm3 (range, 2.0–12.3 cm3). The ejaculatory ducts were usually not well visualized on T2-weighted images. The diameter of the vas deferens was 4 mm in most subjects and did not change with ejaculation.

Figure 4.

Representative sections from the 2D axial T2-weighted fast spin-echo pulse sequence (3500/90) depicting the SV (arrowheads) in a 22-year-old healthy volunteer before (A) and after (B) ejaculation. The reduction in SV cross-section can be observed. In this patient, SV volume decreased by 53% after ejaculation.

Table 2.

Median Pre- and Postejaculation Values and Postejaculation Changes in Prostate and SV Volumes

| Anatomic Region | Pre-ejaculation Volume (cm3) | Postejaculation Volume (cm3) | Change (cm3) | Percentage Change | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prostate | 22.2 (18.3–27.2) | 21.3 (19.3–27.0) | 0.02 (22.3 to 2.4) | 0.8 (210.6 to 12.6) | .53 |

|

| |||||

| SV | 15.1 (10.5–37.2) | 8.2 (6.6–31.9) | 25.6 (212.3 to 2.0) | 244.5 (14–65) | .004† |

Note.—Numbers in parentheses are ranges. For all values, n = 8.

Two-sided Wilcoxon signed rank test was used.

Difference was significant.

Quantitative MR Imaging Parameters

Figures 5–7 show box and whisker plots of T1, T2, and ADC values in each region they were measured. The P values are given, and the asterisks label the significant changes in T2 and ADC that occurred in the PZ after ejaculation. The whiskers denote the maximum and minimum data points, or 1.5× the interquartile range, and the open circles represent outliers.

Figure 5.

Box and whisker plots of pre- and postejaculation mean T1 values, measured over the whole prostate. Whiskers denote the maximum and minimum data points or 1.5× the interquartile range. P value for the two-sided Wilcoxon signed rank test is shown.

Figure 7.

Box and whisker plots of pre- and postejaculation mean ADC values, measured in the CG and PZ. Whiskers denote the maximum and minimum data points or 1.5× the interquartile range. Open circles represent outliers. P value for the two-sided Wilcoxon signed rank test is shown. ∗ = significant change.

Table 3 shows the median and range values of the T1, T2, and ADC quantitative parameter measurements, depicted in Figures 5–7, in each region they were calculated. We list pre- and postejaculation values, the difference, the percentage difference, and the P values for comparison. We did not observe significant changes in T1 values or in CG T2 and ADC values, but PZ T2 and ADC values showed significant decreases, with P = .004.

Table 3.

Median Pre- and Postejaculation Values and Postejaculation Changes in the Quantitative MR Imaging Parameters T1, T2, and ADC

| Parameter | Pre-ejaculation Value | Postejaculation Value | Change | Percentage Change | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 (msec)† | 2040 (1698–2632) | 2020 (1720–2409) | −151 (−458 to 350) | −7.1 (−19.9 to 20.0) | .23 |

|

| |||||

| T2 (msec) | |||||

|

| |||||

| CG | 77 (64–91) | 81 (51–97) | 4 (−14 to 16) | 4.0 (−21.5 to 21.5) | .47 |

|

| |||||

| PZ | 118 (98–212) | 102 (90–193) | −17 (−22 to −7) | −13 (−18.0 to −6.3) | .004‡ |

|

| |||||

| ADC (mm2/sec) | |||||

|

| |||||

| CG | 1.22 (0.95–1.74) | 1.21 (0.95–1.98) | 0.08 (−0.20 to 0.28) | 6.8 (−17.4 to 29.5) | .32 |

|

| |||||

| PZ | 1.30 (1.21–2.08) | 1.20 (1.04–1.61) | −0.18 (−0.47 to −0.04) | −14.5 (−22.6 to −3.1) | .004‡ |

Note.—Numbers in parentheses are ranges. For all values, n = 8.

Two-sided Wilcoxon signed rank test was used.

Calculated over the entire prostate.

Difference was significant.

Discussion

We demonstrated successful MR imaging of the prostate and adjacent structures before, during, and after ejaculation, as well as significant changes in T2 and ADC in the PZ after ejaculation, with potential implications for prostate cancer visualization. Our study of healthy young volunteers showed that, qualitatively, MR images of the prostate did not change dramatically after ejaculation. Upon direct comparison of pre- and postejaculation images, it was possible to discern some changes in contrast within the prostate, mostly on T2-weighted images. Quantitative MR imaging, however, was able to quantitatively demonstrate the extent of such changes in the PZ, on both T2-weighted and ADC images. Thus, the effects of ejaculation may have greater implications for research and diagnostics in the setting of quantitative metrics, as the time since ejaculation may affect the measures of interest.

We were able to measure significant changes after ejaculation in the quantitative MR imaging parameters T2 and ADC measured in the PZ. These are parameters that are clinically relevant for lesion detection (17) and the location where most cancers are detected (23). Our study did not include patients with prostate cancer, so it is not clear whether postejaculation changes would also occur in cancerous tissue. It is also unclear whether changes in cancerous tissue would mitigate or compound the negative effect on lesion conspicuity, given the changes in normal tissue. Similar studies in older subjects with prostate cancer are needed. In addition to changes in lesion contrast, it is possible that the changes in T2 and ADC values in the lesions themselves may occur and correlate with lesion characteristics. For example, lesions with a lower Gleason score have better preserved glandular architecture, with more propensity to have relatively high T2 values and less restricted diffusion (higher ADC values), owing to the fluid in the glandular lumen (24,25). For the same reasons, they may exhibit larger changes in T2 and ADC after ejaculation. This remains to be determined.

The real-time dynamic imaging demonstrated the feasibility of real-time MR imaging of human ejaculation. We were able to demonstrate the contraction and release of the internal sphincter and visualize the ejaculate, even without the benefit of using the endorectal coil for increased signal-to-noise ratio. The timing of the internal sphincter contraction and release, relative to the ejaculation moment, agrees broadly with an earlier US study by Gil-Vernet et al (26).

A prior US study of infertile patients yielded prostate volumes similar to those reported here, but SV volumes were more than two times smaller than what was measured in our population (27). Apart from the fertility status, other possible explanations for this difference are that the mean age of the subjects in the infertility study (36 years) was 13 years older than in our current study (23 years), that the patients may not have been asked to abstain from ejaculation prior to the examination, and that in the prior study, an ellipsoid volume, rather than image segmentation, was used to estimate and calculate SV volume. Although the number of subjects is small, our pre- and postejaculation MR imaging measurements were obtained by using segmentation of the complete SV volume, for higher accuracy.

There were several limitations in our pilot study. Most important, only young, healthy volunteers were recruited. This was done for ease of recruitment in the initial stages of our study, as it might have been difficult to recruit older patients with clinically significant disease without having preliminary data. Young, healthy prostate glands show less benign prostate hyperplasia, the presence of which is typical in older men, and there is also higher signal intensity on T2-weghted images in the PZ as men age. Benign prostate hyperplasia could influence overall prostate volume changes and CG quantitative parameters. Thus, our measurements of prostate and SV volumes and their changes with ejaculation could be biased. More important, the inclusion of only young men means that prostate cancer was not imaged. It remains to be seen how our results may compare with those obtained in an older population with clinically significant disease. Second, the three quantitative parameters were imaged at a single time point immediately after ejaculation, and the time course of the effected changes, which could persist for more than 24 hours (19), was not mapped. This could be addressed by conducting serial imaging during the 1–2 hours after ejaculation or by performing repeat imaging after a longer interval. Finally, the low temporal resolution (6 seconds) of the dynamic imaging of the ejaculation itself should be improved in further studies—by using compressed sensing, for example (28).

In conclusion, we demonstrated successful MR imaging of the prostate and adjacent anatomic structures before, during, and after ejaculation. We were able to visualize the contraction and relaxation of the internal sphincter, as well as the presence of the ejaculate in real time. We report on the significant postejaculatory decrease in volume of the SV and the lack of significant changes in the prostate volume. We demonstrate that, after ejaculation, T2 and ADC values exhibit significant decreases in the PZ, with potential implications for prostate cancer visualization.

Figure 6.

Box and whisker plots of pre- and postejaculation mean T2 values, measured in the CG and PZ. Whiskers denote the maximum and minimum data points or 1.5× the interquartile range. Open circle represents an outlier. P value for the two-sided Wilcoxon signed rank test is shown. ∗ = significant change.

Advances in Knowledge.

■ The sequence of important ejaculatory events, such as internal sphincter contraction and relaxation, as well as appearance of the ejaculate, can be visualized successfully with MR imaging.

■ There was no significant change in the volume of the prostate after ejaculation; however, a large and significant (41%, P = .004) change in the volume of the seminal vesicles was identified.

■ After ejaculation, there was a significant reduction in T2 and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values in the peripheral zone (PZ), by 12% and 14%, respectively (P = .004).

Implications for Patient Care.

■ MR imaging has the potential to be used for evaluation of ejaculation.

■ Since postejaculatory T2 and ADC values in the PZ are significantly lowered, abstinence from ejaculation before an MR imaging examination may increase the conspicuity of prostate cancers.

Abbreviations

- ADC

apparent diffusion coefficient

- CG

central gland

- PZ

peripheral zone

- ROI

region of interest

- SV

seminal vesicles

- 3D

three-dimensional

- 2D

two-dimensional

Footnotes

From the Department of Radiology, University of Chicago, 5841 S Maryland Ave, MC 2026, Chicago, IL 60637.

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest: M.M. No relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. S.S. No relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. A.Y. No relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. A.O. Financial activities related to the present article: none to disclose. Financial activities not related to the present article: author received money from GE Healthcare and Philips Healthcare for consulting; institution received grant money from Philips Healthcare. Other relationships: none to disclose.

Author contributions:

Guarantors of integrity of entire study, M.M., A.Y., A.O.; study concepts/study design or data acquisition or data analysis/interpretation, all authors; manuscript drafting or manuscript revision for important intellectual content, all authors; approval of final version of submitted manuscript, all authors; literature research, M.M., S.S., A.O.; clinical studies, all authors; experimental studies, A.O.; statistical analysis, M.M., S.S., A.O.; and manuscript editing, all authors

References

- 1.Murphy JB, Lipshultz LI. Abnormalities of ejaculation. Urol Clin North Am. 1987;14(3):583–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Witt MA, Grantmyre JE. Ejaculatory failure. World J Urol. 1993;11(2):89–95. doi: 10.1007/BF00182035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barazani Y, Stahl PJ, Nagler HM, Stember DS. Management of ejaculatory disorders in infertile men. Asian J Androl. 2012;14(4):525–529. doi: 10.1038/aja.2012.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshida M, Kudoh J, Homma Y, Kawabe K. Safety and efficacy of silodosin for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Clin Interv Aging. 2011;6:161–172. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S13803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schilit S, Benzeroual KE. Silodosin: a selective alpha1A-adrenergic receptor antagonist for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Clin Ther. 2009;31(11):2489–2502. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffman RM, MacDonald R, Monga M, Wilt TJ. Transurethral microwave thermotherapy vs transurethral resection for treating benign prostatic hyperplasia: a systematic review. BJU Int. 2004;94(7):1031–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tubaro A, Vicentini C, Renzetti R, Miano L. Invasive and minimally invasive treatment modalities for lower urinary tract symptoms: what are the relevant differences in randomised controlled trials? Eur Urol. 2000;38(Suppl 1):7–17. doi: 10.1159/000052397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravery V. Transurethral microwave thermotherapy versus transurethral resection of prostate. Tech Urol. 2000;6(4):267–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choo R, Long J, Gray R, Morton G, Gardner S, Danjoux C. Prospective survey of sexual function among patients with clinically localized prostate cancer referred for definitive radiotherapy and the impact of radiotherapy on sexual function. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(6):715–722. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0675-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huyghe E, Delannes M, Wagner F, et al. Ejaculatory function after permanent 125I prostate brachytherapy for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74(1):126–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sullivan JF, Stember DS, Deveci S, Akin-Olugbade Y, Mulhall JP. Ejaculation profiles of men following radiation therapy for prostate cancer. J Sex Med. 2013;10(5):1410–1416. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung E, Brock G. Sexual rehabilitation and cancer survivorship: a state of art review of current literature and management strategies in male sexual dysfunction among prostate cancer survivors. J Sex Med. 2013;10(Suppl 1):102–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.03005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walz J, Perrotte P, Gallina A, et al. Ejaculatory disorders may affect screening for prostate cancer. J Urol. 2007;178(1):232–237. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.037. discussion 237–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turkbey B, Choyke PL. Multiparametric MRI and prostate cancer diagnosis and risk stratification. Curr Opin Urol. 2012;22(4):310–315. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e32835481c2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yakar D, Debats OA, Bomers JG, et al. Predictive value of MRI in the localization, staging, volume estimation, assessment of aggressiveness, and guidance of radiotherapy and biopsies in prostate cancer. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;35(1):20–31. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Türkbey B, Bernardo M, Merino MJ, Wood BJ, Pinto PA, Choyke PL. MRI of localized prostate cancer: coming of age in the PSA era. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2012;18(1):34–45. doi: 10.4261/1305-3825.DIR.4478-11.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi YJ, Kim JK, Kim N, Kim KW, Choi EK, Cho KS. Functional MR imaging of prostate cancer. RadioGraphics. 2007;27(1):63–75. doi: 10.1148/rg.271065078. discussion 75–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu LM, Xu JR, Ye YQ, Lu Q, Hu JN. The clinical value of diffusion-weighted imaging in combination with T2-weighted imaging in diagnosing prostate carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(1):103–110. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keener TS, Winter TC, Berger R, et al. Prostate vascular flow: the effect of ejaculation as revealed on transrectal power Doppler sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175(4):1169–1172. doi: 10.2214/ajr.175.4.1751169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang HZ, Riederer SJ, Lee JN. Optimizing the precision in T1 relaxation estimation using limited flip angles. Magn Reson Med. 1987;5(5):399–416. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910050502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fram EK, Herfkens RJ, Johnson GA, et al. Rapid calculation of T1 using variable flip angle gradient refocused imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 1987;5(3):201–208. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(87)90021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Homer J, Beevers MS. Driven-equilibrium single-pulse observation of T1 relaxation: a reevaluation of a rapid “new” method for determining NMR spin-lattice relaxation times. J Magn Reson. 1985;63(2):287–297. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Claus FG, Hricak H, Hattery RR. Pretreatment evaluation of prostate cancer: role of MR imaging and 1H MR spectroscopy. RadioGraphics. 2004;24(Suppl 1):S167–S180. doi: 10.1148/24si045516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Epstein JI, Allsbrook WC, Jr, Amin MB, Egevad LL. Update on the Gleason grading system for prostate cancer: results of an international consensus conference of urologic pathologists. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13(1):57–59. doi: 10.1097/01.pap.0000202017.78917.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Epstein JI, Allsbrook WC, Jr, Amin MB, Egevad LL, ISUP Grading Committee The 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(9):1228–1242. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000173646.99337.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gil-Vernet JM, Jr, Alvarez-Vijande R, Gil-Vernet A, Gil-Vernet JM. Ejaculation in men: a dynamic endorectal ultrasonographical study. Br J Urol. 1994;73(4):442–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1994.tb07612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lotti F, Corona G, Colpi GM, et al. Seminal vesicles ultrasound features in a cohort of infertility patients. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(4):974–982. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsao J, Kozerke S. MRI temporal acceleration techniques. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;36(3):543–560. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]