Abstract

Background

Although circumcision for phimosis in children is a minor surgical procedure, it is followed by pain and carries the risk of increased postoperative anxiety. This study examined predictive factors of postoperative pain and anxiety in children undergoing circumcision.

Methods

We conducted a prospective cohort study of children scheduled for elective circumcision. Circumcision was performed applying one of the following surgical techniques: sutureless prepuceplasty (SP), preputial plasty technique (PP), and conventional circumcision (CC). Demographics and base-line clinical characteristics were collected, and assessment of the level of preoperative anxiety was performed. Subsequently, a statistical model was designed in order to examine predictive factors of postoperative pain and postoperative anxiety. Assessment of postoperative pain was performed using the Faces Pain Scale (FPS). The Post Hospitalization Behavior Questionnaire study was used to assess negative behavioral manifestations.

Results

A total of 301 children with a mean age of 7.56 ± 2.61 years were included in the study. Predictive factors of postoperative pain measured with the FPS included a) the type of surgical technique, b) the absence of siblings, and c) the presence of postoperative complications. Predictive factors of postoperative anxiety included a) the type of surgical technique, b) the level of education of mothers, c) the presence of preoperative anxiety, and d) a history of previous surgery.

Conclusions

Although our study was not without its limitations, it expands current knowledge by adding new predictive factors of postoperative pain and postoperative anxiety. Clearly, further randomized controlled studies are needed to confirm its results.

Keywords: Anxiety, Child; Circumcision; Pain measurement; Phimosis; Postoperative pain; Predictive value of tests; Questionnaires

INTRODUCTION

Circumcision for phimosis is one of the most frequent interventions in pediatric surgery [1]. Although regarded as minor and routine, it is a painful procedure [2] which, compounded by general anesthesia and hospitalization, can prove to be a particularly distressing event for children [3]. Furthermore, these disturbing factors may cause such anxiety as to influence pre- and postoperative recovery. It has been shown that patients with lower preoperative anxiety have a better recovery and show fewer emotional and behavioral problems after discharge, while those displaying heightened anxiety have a greater likelihood of suffering a number of negative psychological effects such as anxiety, depression, irritability, aggressiveness and disturbances in their relationship with caregivers [2]. From a medical point of view, perioperative anxiety may affect the immune system by increasing sensitivity to infections [4] and subsequent consumption of analgesics postoperatively [5].

In the present study, we investigated risk factors that may influence the presence of postoperative anxiety and pain in children undergoing elective surgery for phimosis using three different surgical techniques.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a prospective observational cohort study which took place from January 2010 to August 2014. Children included in the study were those with American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) physical status I-II and aged 5 to 14 years that were scheduled for elective out-patient circumcision under general anesthesia. Exclusion criteria included any degree of cognitive and communicative impairment, bleeding disturbances, poor speaking and reading of the Greek language, refusal of parents to participate in the study, or loss to follow-up.

1. Objectives of the study

1) To determine the impact of demographics and base-line clinical characteristics on the degree of postoperative pain.

2) To examine the association between postoperative negative behavior manifestations (NBMs) and demographics, and base-line clinical characteristics.

2. Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and informed consent was obtained from the parents.

3. Definitions

1) Pain: defined as an unpleasant sensory experience associated with tissue damage [6].

2) Anxiety: defined as a response of the brain to stimuli that the organism will attempt to avoid [7].

4. Preoperative protocol

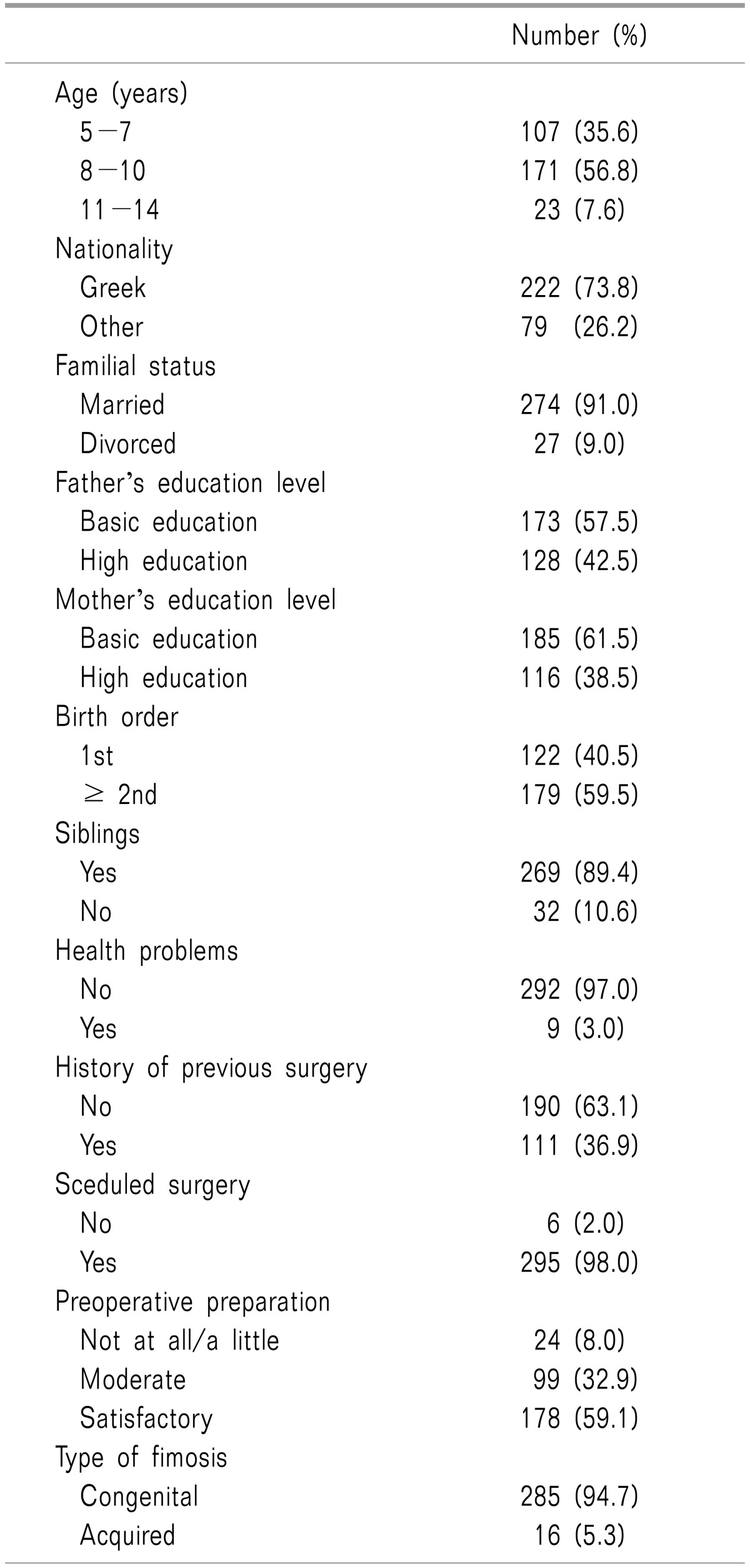

All children and their parents attended a preparation program before surgery (7-10 days before admission to the hospital), which included a visit to the ward and operating room and receiving detailed information concerning the surgical procedure, type of anesthesia, duration of the operation and possible complications. Data collected at this time included age, nationality, familial status, educational level of parents, birth order, health problems, previous surgical experience, schedule of surgery, preparation, and type of phimosis (congenital of acquired) (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographics and Base-line Clinical Characteristics.

On the day of surgery, after separating the children from their parents, preoperative anxiety was assessed in the operating room by an experienced anesthesiologist by using the modified Yale preoperative anxiety scale (m-YPAS) [8] (Table 2). This is a validated observational tool for assessing children's anxiety that focuses on five items: activity, emotional expressivity, state of arousal, vocalization and use of parents. Each item comprises four categories, with the exception of vocalization that has six categories. A partial score is allocated to each item, and the sum is divided by the number of categories within that item. The score of each item is added to the others and the sum is multiplied by 20. Children with a score 23.5-30 are classified as not suffering from anxiety, while a score > 30 denotes severe anxiety [9].

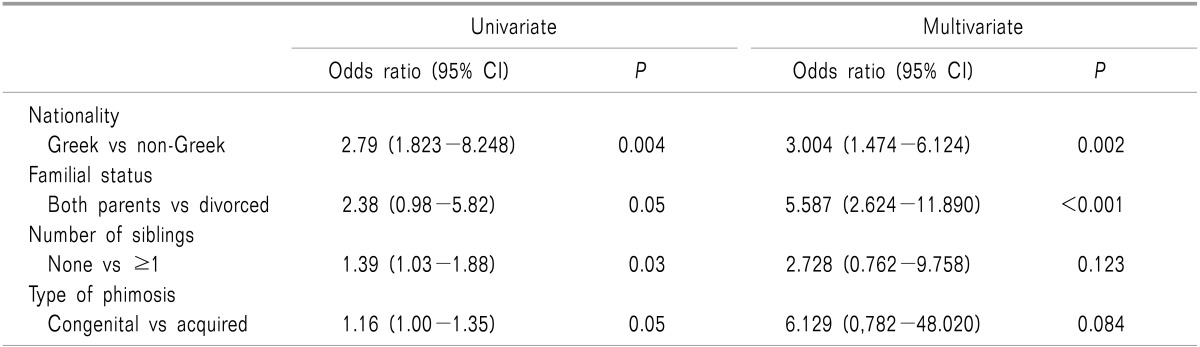

Table 2. Univariate and Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis Demonstrating the Most Significant Factors Related to Preoperative Increased Anxiety.

5. Intraoperative protocol

No premedication was given to the children, and the presence of parents at their child's anesthesia induction was not allowed. General anesthesia was delivered with atropine 0.01 mg/kg, propofol 3 mg/kg and fentanyl 1 µg/kg intravenously. When needed, rocuronium 0.8 mg/kg was used to enable a laryngeal mask of appropriate size to be put in place. Anesthesia was maintained with sevoflurane and O2/N2O. Mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), peripheral oxygen saturation (SPO2), and capnography were monitored during anesthesia. Intraoperative analgesia was estimated on the basis of gross movements or changes in HR and MAP. Increases ≥ 20% of the initial values were recorded and considered as signs of inadequate analgesia.

Following induction of anesthesia and before the start of surgery, a subcutaneous ring block of 0.25% levobupivacaine (0.5% levobupivacaine diluted in normal saline, Chirocaine® , Abbott Laboratories Ltd) was injected around the base of the penis at a dose of 0.1 ml/kg (total dose 0.5 mg/kg). The duration of each surgical procedure (from induction to completion of surgery) was defined as low (10-15 minutes), moderate (15-25 minutes) or increased (25-30 minutes).

Circumcision was performed according to the preference of surgeons. The following surgical techniques were used: conventional circumcision (CC), sutureless prepuceplasty (SP) [10] and preputial plasty (PP) [11]. The complications of the surgical procedures were rated.

6. Postoperative evaluation

On the ward, the doctor responsible (NZ) documented the type of surgical technique and any complication due to anesthetic or surgical interventions. An experienced nurse blinded to the surgical technique assessed postoperative pain according to Bieri's Faces Pain Scale [12]. FPS scores ≥ 3, were considered as an indication of pain. Paracetamol (20 mg/kg) per os or rectum was given when indicated.

7. After discharge

1) Children's NBMs were evaluated according to observations made at home on the 3rd postoperative day. We selected the 3rd postoperative day to avoid the influence of significant pain on NBMs. Studies have shown that pain decreases by the 3rd postoperative day [13]. Vernon's Post Hospitalization Behavior Questionnaire (PHBQ) [14] was chosen to estimate NBMs in children and was offered to the parents in a typed form. PHBQ consists of a list of 27 possible PB traits that children could exhibit. The following domains of anxiety are included in PHBQ: general anxiety, separation anxiety, sleep anxiety, eating disturbances, aggression against authority, and apathy/withdrawal. The children are rated by parents as exhibiting NBM according to the following: (1) much less than before surgery, (2) less than before surgery, (3) the same as before surgery, (4) more than before surgery, and (5) much more than before. The total score ranges from 27 to 135. A score from 27-80 represents fewer NBMs, 81 represents the same as before, and 81-135 represents more. PHBQ has been shown to demonstrate reliability and prediction of changes due to preoperative interventions [15].

2) At home, parents rated their child's pain according to the total doses of analgesics given on the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd postoperative day.

Parents were encouraged to visit the hospital on the 8th postoperative day to allow a second look at the wound, submit the written answers to the PHBQ and provide the recorded total of analgesics given. Alternatively, two doctors (NZ and VN) contacted families by phone.

8. Statistical analysis

The association of each one of the demographics and base-line clinical characteristics with m-YPAS scale and FPS were evaluated using a univariate logistic regression model of analysis. Subsequently, a multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed for those parameters that were proven to be significant in the univariate analysis in order to evaluate the independency of each association, and the statistical significant differences were recorded accordingly. Children were evaluated for NBMs on the 3rd postoperative day and were divided into two groups according to PHBQ scores: those with NBMs and those without NBMs. These groups were further subdivided into two groups according to age: 5-7 years and 8-14 years respectively. Pearson's chi-square test, Fisher's exact test, and Mann-Whitney test were used for the comparison of continuous variables between the two groups. The impact of different factors was compiled and further analysed in a multiple logistic regression analysis in order to find independent factors associated with NBMs. Adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were computed from the results of the logistic regression analyses. All reported P values were two-tailed. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 and analyses were conducted using SPSS statistical software (version 19.0).

RESULTS

After the exclusion of 23 children for various reasons, a total of 301 children (mean age: 7.56 ± 2.61 years) were enrolled in the study. A hundred and seven (35.5%) children were aged 5-7 years, 171 (56,8%) were aged 8-10 years, and 23 (7.6%) were aged 11-14 years. Sample demographics and base-line clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1.

The majority of children (73.8%) were of Greek nationality. In 9% of the sample, the parents were divorced. A separate health problem was reported in nine (3.0%) children, and 111 (36.9%) patients had a history of previous surgery. Surgery was scheduled in almost all cases (98%). In 178 (59.1%) of cases, the preoperative preparation was considered as satisfactory. Preoperative increased anxiety was recorded in 185 (61.5%) children. The univariate logistic regression analysis showed that m-YPAS was increased in children of non-Greek origin and children without siblings (P: 0.004, and P: 0.03, respectively). The same analysis revealed a borderline increase of m-YPAS for children of divorced parents (P: 0.05) and those having acquired phimosis (P: 0.05) (Table 2). However, the multivariate regression analysis showed that preoperative increased anxiety was observed only in children of divorced parents [OR: 5.587 (CI: 2.624-11.890)], P: < 0.001, and in those of non-Greek nationality [OR: 3.004 (95% CI: 1.474-6.124)], P: 0.002 (Table 2).

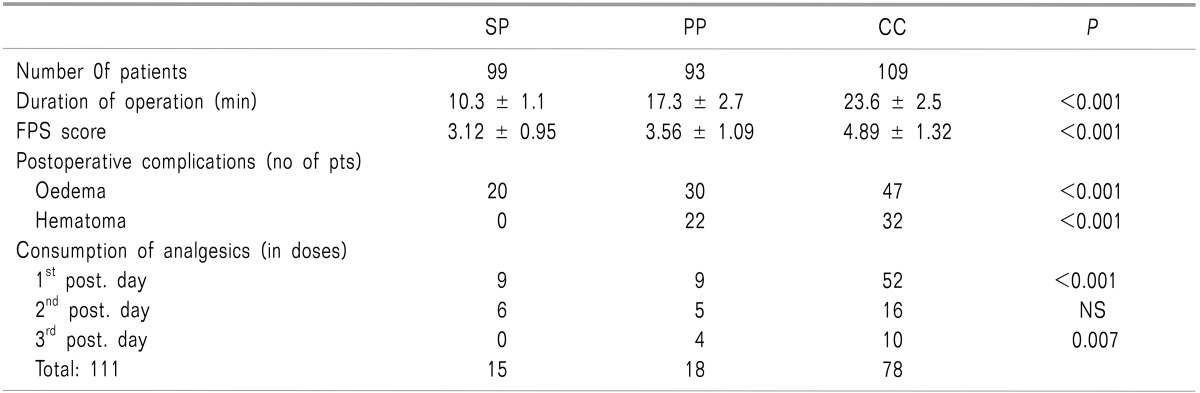

The SP technique was performed on 99 children (32.9%), PP on 93 (30.9%), and CC on 109 (36.2%) (Table 3). Regarding the duration of surgery, the mean time for the SP technique was significantly less (10.25 ± 1.1 minutes) as compared with PP (17.31 ± 2.71 minutes) and CC (23.58 ± 2.48 minutes) (P < 0.001). The mean FPS score was 4.37 ± 1.48 (range 2-8). Patients submitted to CC exhibited statistically higher mean pain scores (FPS: P < 0.001) when compared with the other surgical procedures. Postoperative complications were recorded in 27.7% of cases (edema in 18.7% of the cases, hematoma in 6.7% and both edema and hematoma in 2.3%). The majority (56.3%) were noted in children who underwent the CC procedure (Table 3). Regarding the intake of analgesics at home, a total of 111 doses of analgesics were given over the 1st , 2nd, and 3rd postoperative days: specifically, 70 (63%) doses were given on the 1st postoperative day, 27 (24.3%) on the 2nd and 14 (12.7%) on the 3rd postoperative day.

Table 3. Intraoperative and Postoperative Findings. Results are Expressed as Mean ± SD and %.

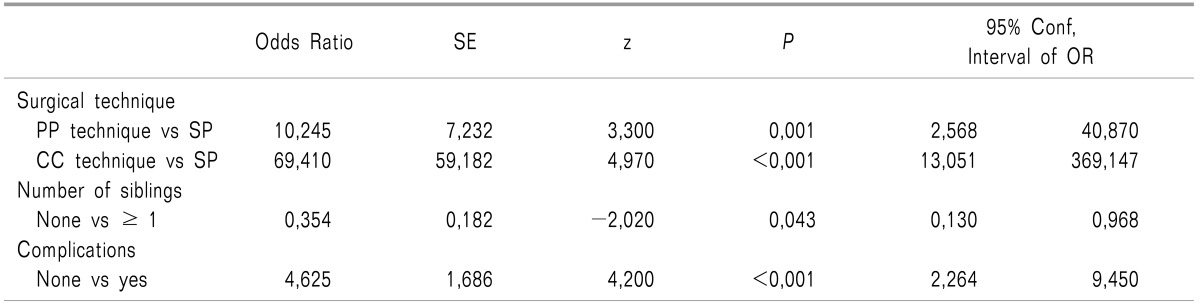

The majority (70.2%) were needed for those children who underwent the CC technique. The results of the multivariate regression analysis showed a strong correlation between the type of surgical technique (PP versus SP and CC versus SP) and the presence of postoperative pain assessed with the FPS [OR: 10.24 and 69.41 (95%CI: 2.568-40.87 and 13.051-369.14 respectively), P: 001, and P < 0.001 respectively] (Table 4).

Table 4. Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis Regarding Demographics, Base-line Clinical Characteristics and FACES Scale.

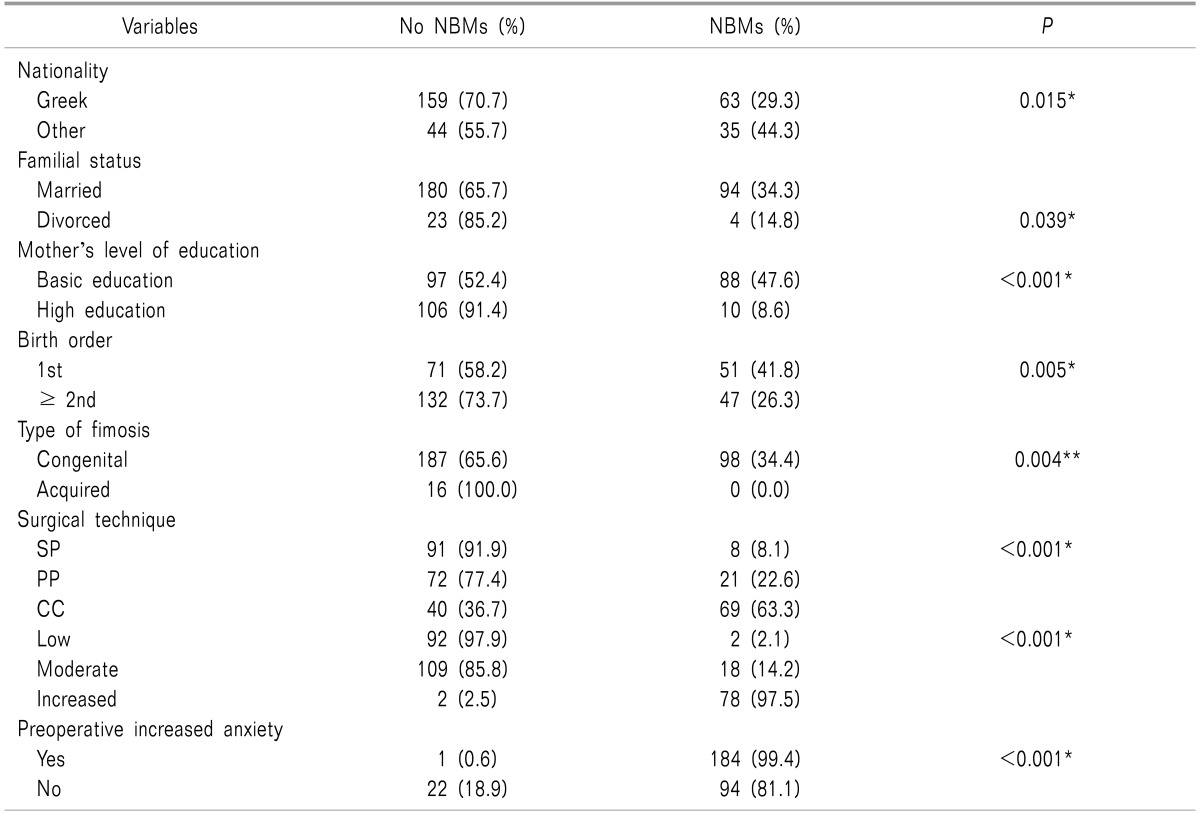

On the 3rd postoperative day, 98 (32.6%) children presented NBMs. Table 5 summarizes the results of the most significant factors that are influenced in the presence of NBMs based on the univariate logistic model. According to this, parental status, mother education level, birth order, no previous experience of surgery, the type of phimosis, the surgical technique, the nationality, the duration of surgery and the level of preoperative anxiety seems to influence the presence of NBMs More specifically, NBMs were seen in cases of children whose parents were divorced and whose mothers had reached only a basic level of education. Significantly higher percentages of NBMs were associated with the first born child and those with no previous experience of surgery. Moreover, the proportion of children with NBMs on the 3rd postoperative day was significantly lower in SP cases as compared with both CC and PP (P < 0.001 for both comparisons), while PP cases exhibited fewer NBMs than those submitted to CC (P < 0.001). The proportion of children with NBMs on the 3rd postoperative day was significantly higher among children of non-Greek origin and in cases of congenital phimosis (P; 0.015). Additionally, the longer the duration of surgery, the higher the number of children with NBMs (P < 0.001). Finally, children with higher levels of preoperative anxiety were found to be at higher risk of developing NBMs postoperatively (P < 0.001).

Table 5. NBMs on 3rd Postoperative Day Associated with the Most Significant Demographic Factors and Clinical Characteristics.

*Pearson's chi-square test, **Fisher's exact test.

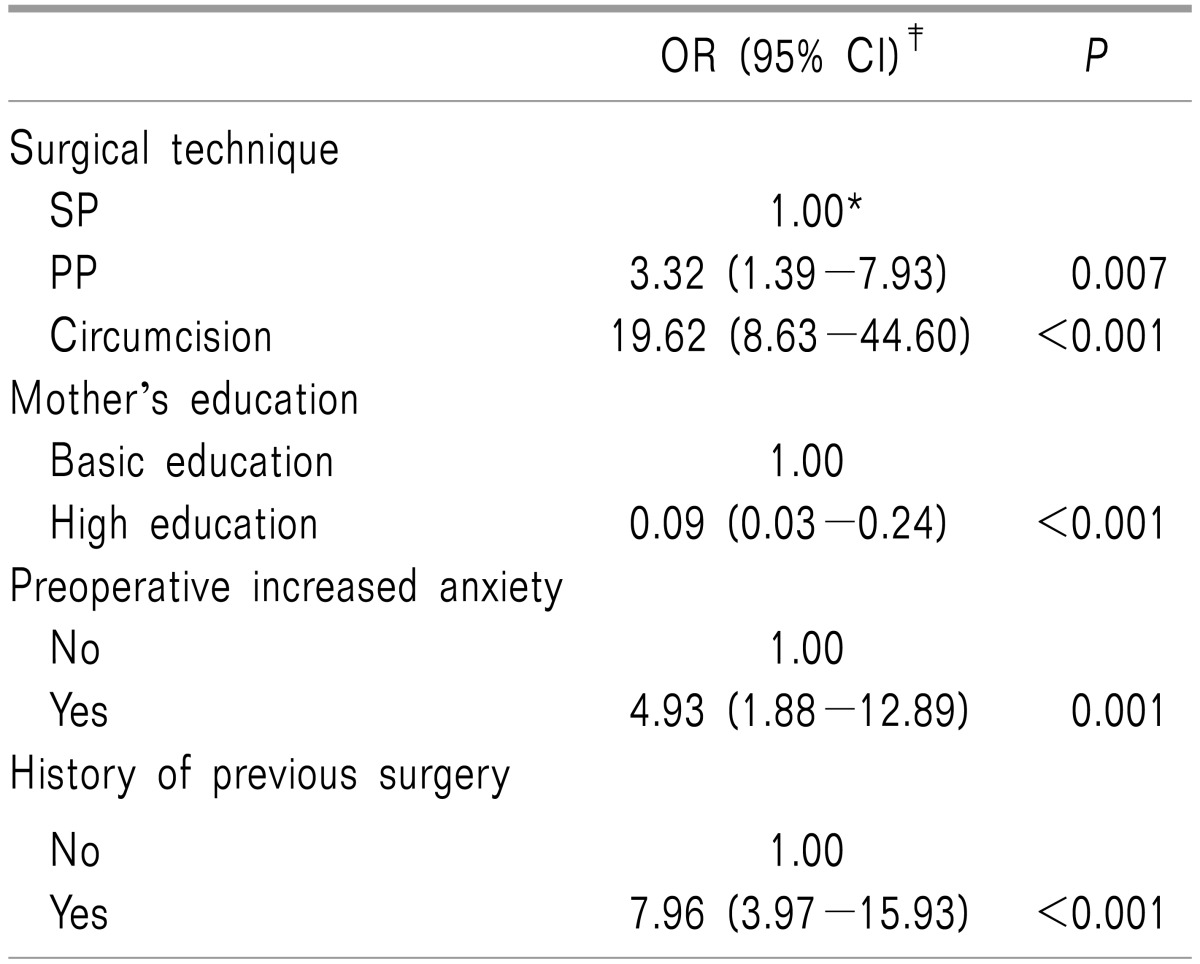

However, when a multiple logistic regression model was applied, it was found that the surgical technique, mother's educational level, preoperative increased anxiety and history of previous surgery were all significantly associated with NBMs (Table 6).

Table 6. Multiple Logistic Regression Results with NBMs Changes on the 3rd Postoperative Day as Dependent Variable.

*Indicates reference category, ‡Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval).

More specifically, children who underwent PP or CC had an estimated greater risk (3.32- and 19.62-fold, respectively) of having NBMs as compared to those who underwent SP surgery. Children whose mothers had achieved a high level of education had 91% lower probability of having NBMs as compared with those whose mothers had reached a basic level of education [OR: 0.09 (95% CI: 0.03-0.24), P < 0.001)] (Table 6). In addition, children with preoperative increased anxiety had 4.93 times greater probability of having NBMs, while those with experience of previous surgery had a likelihood of almost 8 times greater (Table 6).

DISCUSSION

A considerable number of previous studies have focused on the impact of various factors on postoperative NBMs. These factors included preoperative anxiety of parent and child, child's temperament, previous experience of hospitalization for surgery, length of hospitalization, preoperative preparation, preoperative premedication, the presence of parents at the induction of anesthesia and in the post-anesthetic care unit, or the different use of anesthetic drugs provided at induction in anesthesia, [5,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. In the present study, along with some of the above mentioned factors, we studied new factors such as familial status, nationality, and the birth order of children in order to gain more specific information concerning the influence of day-case surgery on NBMs post-discharge.

Liu et al. [25] examined the behavioral problems of children of divorced parents and found that such children had negative consequences including aggressive behavior, withdrawal, and social problems as compared with children with both parents. Similarly, Weaver and Schofield [26] showed that children of divorced families exhibited more behavioral problems compared to those with intact families. However, while the results of our study showed a statistical significance of NBMs in children from divorced families when compared against children with both parents (P: 0.039), the regression analysis did not confirm this observation.

Various stress factors, such as language, discrimination, and parental acculturative stress may be implicated in the presence of psychological distress among immigrant children [27,28,29]. All these factors come under the term acculturation as they are related to the process of cultural psychological changes after the meeting of different cultures between individuals [30]. Acculturation has been studied at length in young adolescents and adults. However, it has not been studied extensively in children [31]. In our study, a statistically significant increase of postoperative NBMs (P < 001) in children of non-Greek nationality was noticed which may reflect the effect of stress factors on the emotional reaction of these children.

Karling and Hägglöf [32] reported that the basic education level of parents acted as a protective factor against general anxiety. Furthermore, they identified that higher education acted as a risk factor for specific NBMs such as general anxiety, regression and apathy/withdrawal [32]. One possible explanation could be the capacity of a highly educated mother to have a better understanding of the harmful aspects of stress. Conversely, the results of both the univariate and multivariate analysis showed that the lower education level of parents may be a contributory factor for postoperative NBMs. Furthermore, in line with Karling and Hägglöf [32], the present study found no evidence that the father's educational level had an impact on postoperative NBMs.

In the present study, a history of previous surgery was a predictive factor for postoperative NMBs, as a statistical difference was observed among children with a surgery-free history and NBMs and those having had previous surgery (P < 0.001). Furthermore, the multivariate logistic model indicated that previous surgical history as an independent variable is a crucial factor for the occurrence of postoperative NBMs. Kain et al. [33], and Kotiniemi et al. [34] reported that children's surgical or medical histories may either worsen or minimize anxiety, depending on the quality of a dreadful event. All these conflicting results indicate that the influence of a previous experience of surgery has not yet been clarified for various reasons such as different methods for assessment of anxiety and different statistical analyses [5].

Notably, the statistical analysis showed that congenital phimosis was a contributory factor for postoperative NBMs, but this observation was not noticed in the multivariate analysis. Furthermore, children submitted to the SP surgical technique expressed less NBMs postoperatively, and this finding was confirmed in the logistic regression model. Although no accurate results could be extracted from this observation, one could hypothesize that this finding is related to less postoperative pain which was observed with the SP technique. Indeed, children undergoing SP suffered less pain when compared with the other two techniques (P < 0.001) and this finding was supported by the multivariate analysis. Another significant finding regarding the surgical technique is that of the duration of surgery. Our result showed that this technique required less operating time, a factor that may influence the presence of postoperative anxiety, i.e. the longer the surgical intervention, the greater the chance of postoperative NBMs [17]. It is noteworthy that postoperative complications were not associated with postoperative NBMs.

Surprisingly, no impact of age on postoperative NBMs was noticed in this study, as opposed to several other studies [33,35,36] that showed age to be a potential factor for postoperative maladaptive behavioral changes. Most of the children affected were under four years of age [35,36]. However, our findings concur with those of Thompson and Vernon [36], in which no association between behavioral changes and age was found. Karling et al. [16] hypothesized that a lack of questions related to behavior in older children may be responsible for this discrepancy. Regarding birth order, our results showed that first born children suffered more from NBMs as compared with second born and third born children (P: 0.005). Although this finding was not verified as a predictor factor in the logistic analysis, it is a new finding which should be investigated in future studies.

Of particular interest was the observation that children with increased preoperative anxiety had a statistically greater risk of postoperative NBMs according to both categorical data and multivariate regression analysis. This observation is in line with the studies by Kain et al. [20] and Fortier et al. [37]. Kain et al. [38] speculated that a possible explanation could be the underlying temperament of the child and the feasibility of adaptation to stressful environmental stimuli. In contrast, preoperative preparation was found not to have any impact in the presence of NBMs postoperatively. Our results are consistent with the findings of Kain et al. [39] who reported that no benefits were gained from behavioral preparation programs in the postoperative period. On the contrary, Margolis et al. [40] noticed that a preparation program based on age adjustments may have a beneficial effect on children postoperatively. All in all, the results published in the international literature are conflicting and further investigation is needed to resolve this issue.

A substantial number of studies have shown that increased preoperative anxiety is associated with higher levels of postoperative pain in children undergoing various surgical procedures [20,41,42,43]. However, this correlation was not found in the present study. Notably, the multivariate logistic analysis showed higher preoperative anxiety in children of divorced parents, and those of non-Greek nationality.

On the basis of our results, the mean FPS score was higher in younger children aged 5-7 years when compared to children aged 8-10 and 11-14 years (P: 0.0018 and P: 0.003 respectively). This evidence is supported by the study of Palermo and Drotar [44]. However, in the proposed multivariate analysis, no relationship between age and postoperative pain was found. This finding is in accordance with a study by Logan and Rose [45] who found no relationship between age and postoperative pain. Conversely, Crandall et al. [46] found that postoperative pain increases with age. In summary, results regarding the influence of age in the perception of pain are inconclusive.

In this study, previous surgical experience, as an independent factor, did not correlate with the intensity of postoperative pain; this finding was in accordance with the univariate statistical analysis. This topic has not yet been clarified. The study by Ericsson et al. [43] supports our results, while Crandall et al. [46] reported lower pain scores in children with previous surgical experience. All these contradictory results reflect the interaction of multiple factors such as the conditions of hospitalization, the reasons for surgery, the presence of postoperative complications, and outcome that may be involved with the presence of postoperative pain [43].

Although nationality, preoperative preparation and the duration of surgery seemed to have an influence on pain intensity postoperatively, these variables had no predictability as separate factors in our model of multivariate analysis. On the contrary, the type of surgical technique, absence of siblings, and presence of postoperative complications seem to affect the intensity of postoperative pain as independent factors. In a previous study [47], the authors noticed that postoperative pain in circumcision was less in cases where cyanoacrylate was used for approximation of wound closure rather than sutures. One possible explanation could be the traction effect of the trauma sutures once they come in contact with clothing [47]. This evidence was supported in our study in cases submitted to the SP technique in which no sutures were used. In addition, the presence of postoperative complications was a predictor of postoperative pain, and the SP technique was accompanied by a lower rate of complications.

Our study had a number of limitations. For example, the study only included children operated on for circumcision. Furthermore, preoperative parental anxiety, children's temperament, and preoperative anxiety of the children in the ward or at induction of anesthesia were not assessed. Furthermore, postoperative behavior alterations were measured once and may therefore not reflect a long-term impact on behavioral status of children. However, some new observations, such as the impact of nationality, the mothers' education level, and the order of birth, should be further investigated in future studies.

References

- 1.Beyaz SG. Comparison of postoperative analgesic efficacy of caudal block versus dorsal penile nerve block with levobupivacaine for circumcision in children. Korean J Pain. 2011;24:31–35. doi: 10.3344/kjp.2011.24.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tree-Trakarn T, Pirayavaraporn S. Postoperative pain relief for circumcision in children: comparison among morphine, nerve block, and topical analgesia. Anesthesiology. 1985;62:519–522. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198504000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wollin SR, Plummer JL, Owen H, Hawkins RM, Materazzo F, Morrison V. Anxiety in children having elective surgery. J Pediatr Nurs. 2004;19:128–132. doi: 10.1016/s0882-5963(03)00146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ader R, Cohen N, Felten D. Psychoneuroimmunology: interactions between the nervous system and the immune system. Lancet. 1995;345:99–103. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caumo W, Broenstrub JC, Fialho L, Petry SM, Brathwait O, Bandeira D, et al. Risk factors for postoperative anxiety in children. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2000;44:782–789. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2000.440703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonica JJ. The need of a taxonomy. Pain. 1979;6:247–248. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beesdo K, Knappe S, Pine DS. Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2009;32:483–524. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kain ZN, Mayes LC, Cicchetti DV, Bagnall AL, Finley JD, Hofstadter MB. The Yale Preoperative Anxiety Scale: how does it compare with a "gold standard"? Anesth Analg. 1997;85:783–788. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199710000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cumino Dde O, Cagno G, Gonçalves VF, Wajman DS, Mathias LA. Impact of preanesthetic information on anxiety of parents and children. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2013;63:473–482. doi: 10.1016/j.bjane.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christianakis E. Sutureless prepuceplasty with wound healing by second intention: an alternative surgical approach in children's phimosis treatment. BMC Urol. 2008;8:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-8-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuckow PM, Rix G, Mouriquand PD. Preputial plasty: a good alternative to circumcision. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:561–563. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(94)90092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bieri D, Reeve RA, Champion GD, Addicoat L, Ziegler JB. The Faces Pain Scale for the self-assessment of the severity of pain experienced by children: development, initial validation, and preliminary investigation for ratio scale properties. Pain. 1990;41:139–150. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)90018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gedaly-Duff V, Ziebarth D. Mothers' management of adenoid-tonsillectomy pain in 4- to 8-year-olds: a preliminary study. Pain. 1994;57:293–299. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vernon DT, Schulman JL, Foley JM. Changes in children's behavior after hospitalization. Some dimensions of response and their correlates. Am J Dis Child. 1966;111:581–593. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1966.02090090053003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vernon DT, Thompson RH. Research on the effect of experimental interventions on children's behavior after hospitalization: a review and synthesis. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1993;14:36–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karling M, Stenlund H, Hägglöf B. Child behaviour after anaesthesia: associated risk factors. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:740–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kain ZN, Wang SM, Mayes LC, Caramico LA, Hofstadter MB. Distress during the induction of anesthesia and postoperative behavioral outcomes. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:1042–1047. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199905000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stargatt R, Davidson AJ, Huang GH, Czarnecki C, Gibson MA, Stewart SA, et al. A cohort study of the incidence and risk factors for negative behavior changes in children after general anesthesia. Paediatr Anaesth. 2006;16:846–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2006.01869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuki K, Daaboul DG. Postoperative maladaptive behavioral changes in children. Middle East J Anaesthesiol. 2011;21:183–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kain ZN, Mayes LC, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Karas DE, McClain BC. Preoperative anxiety, postoperative pain, and behavioral recovery in young children undergoing surgery. Pediatrics. 2006;118:651–658. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kain ZN, Mayes LC, Wang SM, Hofstadter MB. Postoperative behavioral outcomes in children: effects of sedative premedication. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:758–765. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199903000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watson AT, Visram A. Children's preoperative anxiety and postoperative behaviour. Paediatr Anaesth. 2003;13:188–204. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lardner DR, Dick BD, Crawford S. The effects of parental presence in the postanesthetic care unit on children's postoperative behavior: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:1102–1108. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181cccba8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aguilera IM, Patel D, Meakin GH, Masterson J. Perioperative anxiety and postoperative behavioural disturbances in children undergoing intravenous or inhalation induction of anaesthesia. Paediatr Anaesth. 2003;13:501–507. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.01002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu X, Guo C, Okawa M, Zhai J, Li Y, Uchiyama M, et al. Behavioral and emotional problems in Chinese children of divorced parents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:896–903. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200007000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weaver JM, Schofield TJ. Mediation and moderation of divorce effects on children's behavior problems. J Fam Psychol. 2015;29:39–48. doi: 10.1037/fam0000043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duru E, Poyrazli S. Personality dimensions, psychosocial demographic variables, and English language competency in predicting level of acculturative stress among Turkish international students. Int J Stress Manag. 2007;14:99–110. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suarez-Morales L, Lopez B. The impact of acculturative stress and daily hassles on pre-adolescent psychological adjustment: examining anxiety symptoms. J Prim Prev. 2009;30:335–349. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0175-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Behnke AO, MacDermid SM, Coltrane SL, Parke RD, Duffy S, Widaman KF. Family cohesion in the lives of Mexican American and European American parents. J Marriage Fam. 2008;70:1045–1059. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sam DL, Berry JW. Acculturation: when individuals and groups of different cultural backgrounds meet. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2010;5:472–481. doi: 10.1177/1745691610373075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leidy MS, Parke RD, Cladis M, Coltrane S, Duffy S. Positive marital quality, acculturative stress, and child outcomes among Mexican Americans. J Marriage Fam. 2009;71:833–847. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karling M, Hägglöf B. Child behaviour after anaesthesia: association of socioeconomic factors and child behaviour checklist to the Post-Hospital Behaviour Questionnaire. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:418–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kain ZN, Mayes LC, O'Connor TZ, Cicchetti DV. Preoperative anxiety in children. Predictors and outcomes. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150:1238–1234. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170370016002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kotiniemi LH, Ryhänen PT, Moilanen IK. Behavioural changes in children following day-case surgery: a 4-week follow-up of 551 children. Anaesthesia. 1997;52:970–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1997.202-az0337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eckenhoff JE. Relationship of anesthesia to postoperative personality changes in children. AMA Am J Dis Child. 1953;86:587–591. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1953.02050080600004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson RH, Vernon DT. Research on children's behavior after hospitalization: a review and synthesis. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1993;14:28–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fortier MA, Del-Rosario AM, Martin SR, Kain ZN. Perioperative anxiety in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2010;20:318–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2010.03263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kain ZN, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Maranets I, McClain B, Gaal D, Mayes LC, et al. Preoperative anxiety and emergence delirium and postoperative maladaptive behaviors. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:1648–1654. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000136471.36680.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kain ZN, Caramico LA, Mayes LC, Genevro JL, Bornstein MH, Hofstadter MB. Preoperative preparation programs in children: a comparative examination. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:1249–1255. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199812000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Margolis JO, Ginsberg B, Dear GL, Ross AK, Goral JE, Bailey AG. Paediatric preoperative teaching: effects at induction and postoperatively. Paediatr Anaesth. 1998;8:17–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.1998.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pederson C. Effect of imagery on children's pain and anxiety during cardiac catheterization. J Pediatr Nurs. 1995;10:365–374. doi: 10.1016/S0882-5963(05)80034-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bringuier S, Dadure C, Raux O, Dubois A, Picot MC, Capdevila X. The perioperative validity of the visual analog anxiety scale in children: a discriminant and useful instrument in routine clinical practice to optimize postoperative pain management. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:737–744. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181af00e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ericsson E, Wadsby M, Hultcrantz E. Pre-surgical child behavior ratings and pain management after two different techniques of tonsil surgery. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70:1749–1758. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palermo TM, Drotar D. Prediction of children's postoperative pain: the role of presurgical expectations and anticipatory emotions. J Pediatr Psychol. 1996;21:683–698. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/21.5.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Logan DE, Rose JB. Is postoperative pain a self-fulfilling prophecy? Expectancy effects on postoperative pain and patient-controlled analgesia use among adolescent surgical patients. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30:187–196. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crandall M, Lammers C, Senders C, Braun JV. Children's tonsillectomy experiences: influencing factors. J Child Health Care. 2009;13:308–321. doi: 10.1177/1367493509344821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Elemen L, Seyidov TH, Tugay M. The advantages of cyanoacrylate wound closure in circumcision. Pediatr Surg Int. 2011;27:879–883. doi: 10.1007/s00383-010-2741-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]