Abstract

Pseudoxantoma elasticum is a rare, hereditary, multisystemic disease affecting the skin, eye, and cardiovascular system. A twenty-eight-year-old female has presented to emergency unit with the complaint of gastrointestinal hemorrhage. This patient, who had been monitored in the gastroenterology clinic more than 10 times in the past 8 years, noted a repetitive hemorrhage during her previous pregnancy in her history. The examination of the patient revealed the following signs and symptoms: atrophy in the epithelium of the retina pigment; typical angioid streaks and peau d'orange finding in the fundus; thinning of the retinal nerve fiber in OCT (optic coherence tomography); bilateral and reticular papillary lesions with yellowish-color in the neck region (plucked chicken appearance); presence of bleeding foci in fundus; and nephrocalcinosis in kidneys. In light of these symptoms, the patient was diagnosed with pseudoxantoma elasticum. Skin biopsy confirmed the pseudoxantoma elasticum diagnose. PXE is an uncommon, hereditary disease. Early diagnosis of pseudoxantoma elasticum cases, is important for minimalizing systemic complications and informing the other family members through genetic counseling.

Keywords: Pseudoxantoma elasticum, Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage

INTRODUCTION

Pseudoxantoma elasticum (PXE) is a connective tissue disease showing an incidence of 1/100 000 and characterized by skin, eye, and cardiovascular system involvements. Patients are presented to physicians with skin lesions, advanced loss of vision, significant bleedings in the gastrointestinal system, and intermittent claudication due to presence of abnormal elastic fibers inclined to calcify. While generally, autosomal recessive inheritance is determined (80%), autosomal dominant and sporadic cases have been reported, as well[1-4]. No specific geographical region or race has been identified. A mutation in the gene which codes ABCC6 (MRP6) transmembrane transporter protein, was reported to be a possible cause of PXE[1-7].

CASE REPORT

The 28-year-old female patient who had experienced 12 endocopies due to upper gastrointestinal system hemorrhages occuring more than 10 times during the last 8 years, was presented to our gastroenterology clinic. As a result of those endoscopic examinations applied since her first bleeding complaint in 1999, because no findings associated with peptic ulcer, portal hypertension, and malignity could have been determined, the patient had been diagnosed with bleeding foci in fundus, erosive gastritis, and bulbar erosion. In her last presentation, while hemorrhage foci were present in the fundus, there were no predisposing causes such as stress, nonsteroid drug usage, dietary change, cigarette, and alcohol. Because the patient was pregnant and there were no active hemorrhage foci in the endoscopy, only antacid therapy and dietary treatment were applied. After 3 d of her discharge, the patient again presented to our clinic with acute upper GIS hemorrhage. The emergency endoscopy revealed an active, intense bleeding focus in fundus and due to application of an hemoclip (Olympus-EndoTherapy EZ-clip standard type HXE-610-135 DEG) in the same session, bleeding was stopped.

The physical examination of the patient revealed bilateral and reticular yellowish papillary lesions in the neck (plucked chicken appearance), and 10-15 red-purple colored nodular lesions (hemangioma) with regular contours and 4-8 mm largeness around the right ear. Lesions similar to the ones found in neck, were observed in inguinal region and axillary regions as well. No significant lesion was determined in oral mucosa, head and skin with hair, upper extremities, and body trunk.

Detailed dermatological examination of the patient revealed: typically grey-white colored papillary lesions displaying a plucked chicken appearance in the anterior part of the neck, and typical brown-yellow lesions in neck, axillary, and inguinal regions. As a result of the dermatological consultation performed for lesions localized in neck, axillary, and inguinal regions; patient was diagnosed with pseudoxantoma elasticum (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

View of the patient’s skin from neck region.

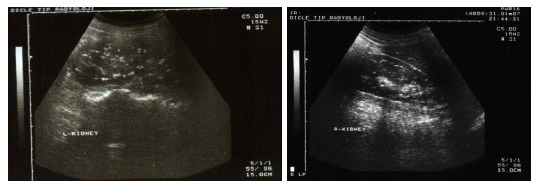

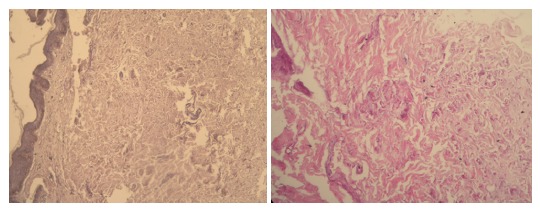

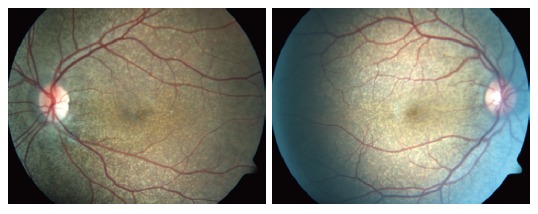

The laboratory results of our patient; routine biochemical investigations, viral and tumoral markers, autoimmune liver tests, and coagulation tests, were normal except a finding of low albumin level (2.3 gr/dL). Abdominal-pelvic USG revealed a singular fetus in uterus consistent with 17 wk and a diffuse nephrocalcinosis in cortex and medulla of both of the kidneys (Figure 2). The skin tissue sample observed in neck and taken by excisional biopsy and stained with specific chromogranin techniques and HE, showed a degeneration and change of size in collagen and elastic fibers localized in focal areas of middle and deep dermis in the tissue covered with stratified squamous epithelium. The findings were reported to be consistent with pseudoxantoma elasticum (Figure 3). Eye examination revealed; atrophy in retinal pigment epithelium, angioid streaks and typical peau d'orange sign in fundus (Figure 4), and a thinning of retinal nerve layer by OCT (optic coherence tomography). However, fluorescent angiography procedure couldn’t have been applied by the ophtalmology clinic due to pregnancy. No pathological results were observed in cardiological examination of our case.

Figure 2.

Nephrocalcinosis findings in both of the kidneys.

Figure 3.

Degeneration in reticular fibers of dermis (HE).

Figure 4.

An appearance consistent of peau d'orange sign, peripapillary atrophy, and angioid streak in both of the eyes.

DISCUSSION

Pseudoxantoma elasticum is a rare hereditary disease with an incidence of 1/100 000, affecting mostly skin, eye, and cardiovascular system. It may be seen in any human race, female/male incidence rate was reported as 2:1[1-8]. In the present case, “angioid streaks” were determined in examination of the fundus oculi. This lesion is observed as grey-red linear streaks extending below retinal vasculature and surrounding the optic disc. Tearing and calcification of the elastin-rich outer layer of the Bruch membrane leads to this disease[9]. Angioid streaks could be observed in Paget disease (osteitis deformans), Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and hemolytic anemies as well[1]. Pseudoxantoma elasticum symptoms were determined by dermatology consultation and histological examination of the skin alongwith the presence of typical fundus oculi finding. Furthermore, a less commonly seen eye symptom of PXE, leopard spotting in the posterior pole, was present as well. The other less commonly encountered eye symptoms such as; comet-like streaks, drusen, reticular pigmental dystrophia of the macula, and focal atrophic pigmented epithelium, were not present in this case.

Skin lesions are commonly seen in PXE cases, especially between age of 20-25 in the early period of the disease[10-14]. Generally, skin is observed to be wrinkled and flaccid. Lesions are mostly observed in antecubital and popliteal fossa, inguinal region, and periumbilical regions, as yellowish papillas with 1 mm or so diameter. Involvement of face, lip, oral mucosa, soft palate, and nasal mucosa may be present in a much less frequent fashion. In the present case, one of the lesions observed in the neck, was removed by excisional biopsy. As a result of the examination of the tissue sample, our case was diagnosed as pseudoxantoma elasticum. There is one reported case in which PXE and calcinosis cutis were reported in association[8]. In cases where the clinical findings are not satisfactory; calcific elastosis, calciphylaxis, penicillamin intoxication, and solar elastosis should be considered for the histopathological differential diagnosis in light of the findings obtained from the biopsy material. Apart from the PXE, in perforated calcific elastosis, calcified elastic fibers pass through epidermis by a channel and reach the surface. The distinction of calcific elastosis without perforation is difficult and the associated ocular and cardiovascular system findings are evaluated in favor of PXE. However, in solar elastosis, the abnormal elastic tissue not stained with calcium, is observed in superficial dermis, as a mass instead of singular fibers.

Calciphylaxis is a serious clinical condition mostly developing due to presence of chronic renal insufficiency associated with hyperparathyroiditis. As a result of the disruption of calcium-phosphate balance; calcium phosphate salts are built-up in trauma area, injection focus, and small to midsize subcutaneous vessels. Due to long-term penicillamin usage, lesions such as anetoderma and elastosis perforans serpiginosa may be see[12]. Cardiovascular system results may not be as apparent as ocular and cutaneous results. However, there is a reported case including a sudden death secondary to cardiac involvement in the literature[15,16]. Clinically, besides presence of angina pectoris and intermittent claudication due to involvement of both internal and external elastic laminas of coronary arteries and peripheral large arteries, as a result of the degeneration of only the internal elastic membrane of thin-walled vessels in stomach mucosa, hematochezia or melena may be determined[6,7,12]. In our case, there was no angina pectoris history. To date, the PXE gene was determined to be on 16p13.1 localization with a distance of 500 kb. Gen mutation named as ABC-C6 (MRP-6), has been identified in 80% of cases showing PXE phenotype[17,18]. Generally, the presence and severity of clinic results in PXE cases (skin, eye, vascular) have not been associated with inheritance modality. The differention of the results even in the same family members, indicates the mixed nature of the disease requiring appropriate environmental conditions such as diet or hormonal status, alongwith genetic predisposition[5,6]. In light of this case, the importance of applying systemic and genetic screening due to consideration of PXE in differential diagnosis for the same family members manifesting xantomatous skin lesions, was underlined.

In conclusion, pseudoxantoma should be considered and investigated by skin biopsy in especially female cases with pregnancy and repetitive hemorrhage of upper gastrointestinal system when specific skin and eye symptoms are present in neck, axillary, and inguinal regions. In upper gastrointestinal system bleedings without any apparent cause, pseudoxantoma elasticum diagnose should be considered and investigated.

Footnotes

Editor Liu Y L- Editor Alpini GD E- Editor Liu Y

References

- 1.Bercovitch L, Terry P. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum 2004. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:S13–S14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ringpfeil F, Lebwohl MG, Christiano AM, Uitto J. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: mutations in the MRP6 gene encoding a transmembrane ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6001–6006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100041297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergen AA, Plomp AS, Schuurman EJ, Terry S, Breuning M, Dauwerse H, Swart J, Kool M, van Soest S, Baas F, et al. Mutations in ABCC6 cause pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Nat Genet. 2000;25:228–231. doi: 10.1038/76109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pulkkinen L, Nakano A, Ringpfeil F, Uitto J. Identification of ABCC6 pseudogenes on human chromosome 16p: implications for mutation detection in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Hum Genet. 2001;109:356–365. doi: 10.1007/s004390100582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plomp AS, Hu X, de Jong PT, Bergen AA. Does autosomal dominant pseudoxanthoma elasticum exist? Am J Med Genet A. 2004;126A:403–412. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chassaing N, Martin L, Mazereeuw J, Barrié L, Nizard S, Bonafé JL, Calvas P, Hovnanian A. Novel ABCC6 mutations in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:608–613. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi Y, Terry SF, Terry PF, Bercovitch LG, Gerard GF. Development of a rapid, reliable genetic test for pseudoxanthoma elasticum. J Mol Diagn. 2007;9:105–112. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2007.060093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hacker SM, Ramos-Caro FA, Beers BB, Flowers FP. Juvenile pseudoxanthoma elasticum: recognition and management. Pediatr Dermatol. 1993;10:19–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1993.tb00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Secrétan M, Zografos L, Guggisberg D, Piguet B. Chorioretinal vascular abnormalities associated with angioid streaks and pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:1333–1336. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.10.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Contri MB, Boraldi F, Taparelli F, De Paepe A, Ronchetti IP. Matrix proteins with high affinity for calcium ions are associated with mineralization within the elastic fibers of pseudoxanthoma elasticum dermis. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:569–577. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li TH, Tseng CR, Hsiao GH, Chiu HC. An unusual cutaneous manifestation of pseudoxanthoma elasticum mimicking reticulate pigmentary disorders. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:1157–1159. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb07970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uenishi T, Uchiyama M, Sugiura H, Danno K. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum with generalized cutaneous laxity. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:664–666. doi: 10.1001/archderm.133.5.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lebwohl M, Phelps RG, Yannuzzi L, Chang S, Schwartz I, Fuchs W. Diagnosis of pseudoxanthoma elasticum by scar biopsy in patients without characteristic skin lesions. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:347–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198708063170604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buka R, Wei H, Sapadin A, Mauch J, Lebwohl M, Rudikoff D. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum and calcinosis cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:312–315. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.106472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schachner L, Young D. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum with severe cardiovascular disease in a child. Am J Dis Child. 1974;127:571–575. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1974.02110230117021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenzweig BP, Guarneri E, Kronzon I. Echocardiographic manifestations in a patient with pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:487–490. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-6-199309150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uitto J, Pulkkinen L, Ringpfeil F. Molecular genetics of pseudoxanthoma elasticum: a metabolic disorder at the environment-genome interface? Trends Mol Med. 2001;7:13–17. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(00)01869-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luft FC. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum revealed. J Mol Med (Berl) 2000;78:237–238. doi: 10.1007/s001090000119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]