Significance

The political integration of immigrant minorities is one of the most pressing policy issues many countries face today. Despite heated debates, there exists little rigorous evidence about whether naturalization fosters or dampens the integration of immigrants into the political fabric of the host society. Our study provides new causal evidence on the long-term effects of naturalization on political integration. Our research design takes advantage of a natural experiment in Switzerland that allows us to separate the independent effect of naturalization from the nonrandom selection into naturalization. We find that in our sample, naturalization caused long-lasting improvements in political integration, with immigrants becoming likely to vote and attaining considerably higher levels of political efficacy and political knowledge.

Keywords: naturalization, immigration, integration, natural experiment, citizenship

Abstract

Does naturalization cause better political integration of immigrants into the host society? Despite heated debates about citizenship policy, there exists almost no evidence that isolates the independent effect of naturalization from the nonrandom selection into naturalization. We provide new evidence from a natural experiment in Switzerland, where some municipalities used referendums as the mechanism to decide naturalization requests. Balance checks suggest that for close naturalization referendums, which are decided by just a few votes, the naturalization decision is as good as random, so that narrowly rejected and narrowly approved immigrant applicants are similar on all confounding characteristics. This allows us to remove selection effects and obtain unbiased estimates of the long-term impacts of citizenship. Our study shows that for the immigrants who faced close referendums, naturalization considerably improved their political integration, including increases in formal political participation, political knowledge, and political efficacy.

One of the key debates over immigration policy involves the political integration of immigrants and their access to citizenship. Some argue that immigrants should be given easy access to citizenship and encouraged to naturalize because naturalization provides immigrants with the necessary resources and incentives to rapidly integrate and invest in a future in the host country. In this view, the acquisition of citizenship is an important catalyst that has an independent effect on accelerating and deepening the process of political integration. In contrast, others argue that access to citizenship should be highly restricted because naturalization itself does little to foster integration. In fact, naturalization is likely to dampen the incentives to integrate because once immigrants are given the passport of the host society, they can no longer be motivated to integrate by the promise of obtaining the benefits that come with citizenship (e.g., access to welfare benefits or the right to stay in the country indefinitely). From this perspective, citizenship is not an instrument to improve integration but merely a reward that is promised to immigrants in exchange for successfully completing the integration process. However, others argue that pressuring immigrants to naturalize might backfire and simply reinforce immigrant identities.*

Does naturalization promote political integration? Despite the importance of this question for the design of immigration and citizenship policy and much theorizing among social scientists and pundits, there exists little rigorous causal evidence on the impacts of naturalization on the political integration of immigrants. Most studies only examine the impact of naturalization on economic integration (see, for example, ref. 5), and the few existing studies that consider effects on political integration by comparing the political participation of naturalized and nonnaturalized immigrants are based on limited research designs and data that prevent them from isolating the independent effect of naturalization from a plethora of confounding factors (see, for example, ref. 6 and references therein).

When trying to isolate the effect of naturalization, the key problem for causal inference is that naturalization is far from randomly assigned. Instead, the process through which immigrants obtain citizenship involves a complex double selection process. In the first stage, immigrants selectively apply for naturalization, and this decision often depends on characteristics that are not observed by the researcher. For example, immigrants who are more motivated, have more resources, or are better informed are more likely to apply (see, for example, refs. 7 and 8). In the second stage, decision makers carefully select who among the applicants is approved or rejected for citizenship. This screening is also based on characteristics that are typically unobserved by the researcher. For example, applicants who make a bad impression in the application interview, have a low perceived integration potential, or lack sufficient language skills might be more likely to be rejected.

This double selection process severely confounds the existing comparisons of naturalized and nonnaturalized immigrants. For example, if we find that naturalized immigrants are politically more informed or earn higher wages than nonnaturalized immigrants, we cannot conclude that these differences are caused by naturalization because the double selection ensures that the two groups differ on the many important confounding characteristics. Eliminating the bias from this double selection process is a rather hopeless endeavor with typical observational data because researchers cannot possibly measure and statistically control for the myriad reasons that determine why immigrants apply and why decision makers approve or reject applications.

We provide new evidence that takes advantage of a natural experiment to identify the long-term effects of naturalization on the political integration of immigrants in Switzerland. Before 2003, some Swiss municipalities used secret ballot referendums as the mechanism to decide on naturalization applications. Voters received voting leaflets that informed them about the applicants and then cast a secret ballot to approve or reject each applicant. Immigrants who gained a majority of “yes” votes received the Swiss passport. This setting allows us to remove the bias from the double selection process.

In contrast to previous studies that do not measure whether immigrants applied for citizenship or not, we can remove the first-stage bias from selection into applying because we can restrict the comparison with only those immigrants who applied for naturalization and faced referendums, thereby removing from the control group those immigrants who were not motivated or lacked the resources to apply. We can also remove the second-stage bias from selection into approval using two different identification strategies. First, because we measure the same applicant characteristics that were reported to voters when they voted on the applicants, we can control for the characteristics that determined the approval of applicants and identify the effect of naturalization under a selection on observables assumption. In other words, once we control for their reported characteristics, the applicants are observably equivalent to voters, and therefore, they can no longer screen applicants based on unobservable attributes, such as their integration potential. Second, we can apply a regression discontinuity (RD) design that compares the outcomes of immigrants whose naturalization requests were barely approved or barely rejected by voters. Balance checks suggest that in close referendums that are decided within a narrow vote margin, who gets the Swiss passport and who does not is essentially as good as randomly assigned. Therefore, lucky applicants who are narrowly approved and unlucky applicants who are narrowly rejected are similar on all confounding characteristics, and any differences in their integration outcomes can be attributed to the independent effect of naturalization.

What we find is that naturalization has a strong independent effect on improving the long-term political integration among the competitive immigrant applicants in our sample, including increases in formal political participation, political knowledge, and political efficacy. These effects are robust across the different identification strategies and also large in substantive terms. For example, when looking at our summary index of political integration that combines all outcomes, we find that naturalization causes more than a full standard deviation (SD) unit increase in the political integration index.

Our study makes four main contributions. First, we provide new evidence of the effects of citizenship on the integration of immigrants that takes advantage of a natural experiment where naturalization is as good as randomly assigned. The results suggest that naturalization can act as a catalyst that helps to turn immigrants into “citizens” in the Tocquevillian sense. Second, because the average naturalized immigrant in our sample obtained the Swiss passport 13 y ago, we examine whether naturalization has any long-term effects on incorporating immigrants into the democratic process. Existing work typically only considers short-term outcomes. Third, whereas most studies have looked at the economic integration of immigrants, we provide evidence on the effect of naturalization on the political integration of immigrants. The political integration of immigrants is a major challenge for many countries that face rising immigrant populations and anti-immigrant backlash among natives. Successfully incorporating immigrants into the political process matters not only for the immigrants but also for the quality of the democracy in the host country because such integration enables immigrants to voice their grievances through legitimate electoral and nonelectoral means rather than sporadic violence and terror. Finally, our study fills a gap by examining the effect of naturalization on political integration in Switzerland specifically, a country where immigrant integration is a particularly controversial issue, given the exceptionally large immigrant population (24%) and rather divisive immigration debates in recent decades.

Materials and Methods

Setting.

In Switzerland, naturalization requests are typically decided at the local level, and municipalities use different procedures for these decisions (9, 10). Our study exploits that some municipalities, which we refer to as “ballot box” municipalities, for several decades used popular votes with secret ballots to decide on citizenship applications (ref. 9 describes this institution in detail). Immigrants seeking naturalization had to apply with their local municipality, and if deemed eligible, their naturalization request was put to a popular vote. Resident citizens received an official voting leaflet with résumés that detailed information about each applicant, and voters then cast a secret ballot to reject or approve each naturalization request. Applicants who received a majority of “yes” votes were granted Swiss citizenship (see the SI Appendix for further details about the process).

Identification Strategies.

The use of naturalization referendums allows us to address the double selection bias and thereby improve over existing research. The first improvement is that we can remove the potent confounding that comes from the selection into applying because we can restrict our comparison with immigrants who were all sufficiently motivated enough to apply for Swiss citizenship in the first place. The second improvement is that in the naturalization referendums, we actually know the assignment mechanism that determines why applicants are accepted and can exploit this for identification.

In particular, the unique situation allows for two identification strategies. First, we can identify the effects of citizenship based on a selection on observables assumption because we know and control for the applicant characteristics that voters saw on the voting leaflets when they voted on the naturalization requests. In other words, because voters base their decisions on the applicant characteristics that we observe, once these covariates are controlled for, applicants are observably equivalent to voters such that they cannot strategically and systematically screen applicants for citizenship based on their integration potential or other unobserved characteristics that would confound the comparison. Therefore, in our unique setup, controlling for the observable characteristics should be sufficient to remove almost all of the omitted variable bias (see ref. 9 for further evidence on the selection on observables assumptions).

One remaining caveat with this identification strategy is that a fraction of applicants who were rejected in their first referendum subsequently reapplied and secured citizenship. Simply excluding these successful reapplicants from the analysis would compromise the identification because the decision to reapply is partially endogenous; more motivated immigrants might be more likely to reapply. In addition, there is a possibility that decision makers screen the reapplicants based on unobserved confounding characteristics. Many of the reapplications occurred after 2003 and were therefore not decided in referendums but by politicians in the municipality council. In these cases, we cannot be sure that our covariates capture all of the relevant characteristics that determined the decisions on the reapplications.

Fortunately, we can address this problem using an instrumental variable (IV) approach where identification relies solely on the exogenous variation in naturalization that comes from whether applicants won their first referendums. We follow the IV framework developed by Angrist et al. (11), which allows for heterogeneous treatment effects. We can view the outcome of the first referendum as an exogenous “encouragement,” where winning applicants are encouraged to obtain citizenship and losing applicants are discouraged from obtaining citizenship. Because applicants who win their first referendum automatically obtain citizenship, we only have two types of applicants in our sample: “compliers” and “always takers” (11). Compliers are those applicants who are motivated to apply only once. Compliers obtain Swiss citizenship when they win their first referendum but do not reapply and subsequently naturalize when they lose their first referendum. In other words, such applicants “comply” with the encouragement, and therefore their naturalization status is exogenously determined by the outcome of their first referendum. Always takers are applicants who do not comply with the encouragement because they always obtain Swiss citizenship, regardless of the outcome of their first referendum. If always takers win, they obtain Swiss citizenship, but if they loose, they reapply and subsequently naturalize nonetheless. The IV strategy addresses this noncompliance by taking the (covariate-adjusted) difference in the outcomes between accepted and rejected applicants (the so called intention-to-treat effect) and scaling the difference in the outcomes by the fraction of compliers (the so-called compliance ratio) to isolate the local average treatment effect (LATE) of naturalization among compliers (11).†

Our second identification strategy is a RD design that takes advantage of close referendums and compares lucky applicants who won their naturalization referendum by a few votes and obtained the Swiss passport with unlucky applicants who lost their referendum by a few votes and did not receive the Swiss passport (12). In close referendums, the outcome is largely decided by random factors (e.g., the weather on the day of the referendum, current events, etc.), so that lucky immigrants who are narrowly approved are on average similar to unlucky immigrants who are narrowly rejected, and therefore differences in their integration outcomes can be attributed to the effect of citizenship as opposed to differences in unobserved background factors. In other words, in this quasiexperimental comparison, the applicant characteristics are controlled for “by design” because in close referendums, citizenship is as if it were randomly assigned in an experiment. The key RD identification assumption is that the potential outcomes are continuous at the threshold (13). This assumption would fail if immigrants had precise control over their referendum outcomes and could sort around the threshold, but this is implausible in large elections such as our secret ballot referendums, where the outcome is clearly beyond the control of the individual applicants.

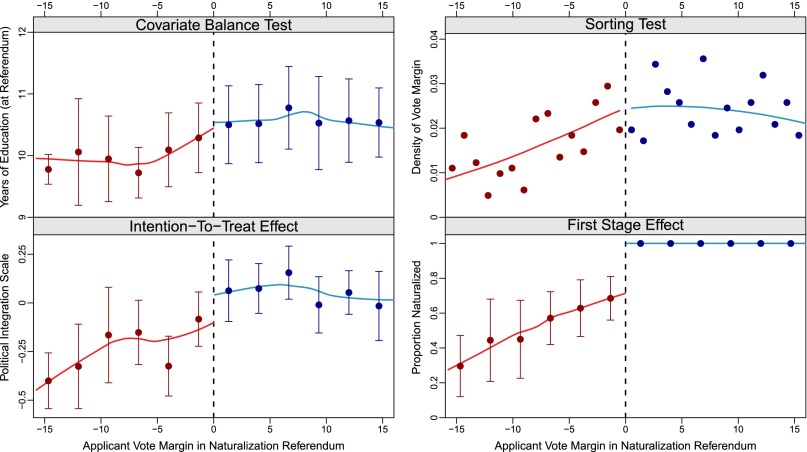

Fig. 1 illustrates the RD logic and previews the main result. In Fig. 1, Upper Left, we plot the applicants’ years of education, as reported on the leaflets at the time of the referendums, against the vote share margin from the applicants’ first naturalization referendum. The vote margin is the difference between the share of “yes” votes and the 50% victory threshold that applicants had to exceed to win their referendum. Applicants with positive (negative) margins to the right (left) of the threshold reached a majority (minority) of “yes” votes and were granted (denied) Swiss citizenship. The red and blue fitted lines from a Loess smoother summarize the average years of education for a given vote share on both sides of the threshold, respectively. The dots are binned averages with 95% confidence intervals.

Fig. 1.

Fuzzy RD design: identification checks and the effect of naturalization on political integration. Upper Left shows that the applicants’ (pretreatment) years of education are well balanced at the vote threshold for winning the naturalization referendum. Upper Right shows that there is no discontinuity in the density of the vote margin variable, indicating that applicants are not sorting around the threshold of winning. Lower Left and Lower Right show that barely winning versus barely losing the referendum increased levels of political integration and the probability of naturalization, respectively. Loess lines; 95% confidence intervals for binned averages (dots).

In close referendums that are decided by just a few votes, who wins and who loses is as good as randomly assigned, and therefore, just as in a truly randomized experiment, close winners and close losers have similar levels of education. SI Appendix, Figs. S3–S6 report similar balance checks that show that barely accepted and barely rejected applicants are similar on many other pretreatment characteristics, including the year of the referendum, their age, sex, prior residency in Switzerland, country of origin, or the average municipality size.

Fig. 1, Upper Right shows another key identification check, where we plot the estimated density of the vote margin on both sides of the threshold. If naturalization is beneficial and applicants had precise control over the outcome of their referendums, then we would expect them to sort around the threshold, and we should therefore see an unusually large (small) number of applicants with vote shares just above (below) the threshold (14). Instead, we find that there is no discontinuity in the density at the threshold, indicating that applicants were not able to sort around the threshold.

Fig. 1, Lower Left previews one of the main findings. We plot the applicants’ score on the political integration scale, our summary measure that combines all integration outcomes, against the vote margin. We see that levels of political integration as measured by the political integration scale sharply increase by about 0.15 right at the threshold. This intention-to-treat effect, which amounts to about a third of a SD unit increase on the integration scale, is causally attributable to the effect of winning the referendum, given that who wins and who looses in close referendum is as good as randomly assigned.

Note that this intention-to-treat effect underestimates the actual effect of naturalization because a sizable share of those who barely lost subsequently reapplied and received Swiss citizenship. We can correct for this noncompliance by using a fuzzy RD design where, similar to the IV strategy, the intention-to-treat effect is scaled by the compliance ratio at the threshold to isolate the LATE of naturalization for compliers in close referendums (13). Fig. 1, Lower Right shows the first-stage effect, where we plot the proportion of naturalized applicants against the vote share margin. We see that the probability of naturalization jumps by about 0.28 at the threshold. Accordingly, the LATE of naturalization for compliers at the threshold is estimated at about 0.15/0.28 = 0.53, which implies that naturalization caused more than a full SD unit increase on the political integration scale.

The two identification strategies are complementary. The IV strategy provides more precision because it identifies the LATE for compliers in the whole estimation sample, but we have to statistically adjust for the covariates. The RD strategy is more nonparametric because we control for the covariates by design, but we lose precision and external validity because we identify the LATE for compliers in close referendums.

Sample.

Our study draws on the data collected by Hainmueller and Hangartner (9), who extracted from municipal archives all of the voting and applicant data for all immigrants whose naturalization requests were decided by such referendums in all 46 ballot box municipalities between 1970 and 2003. In 2003, the Swiss court ruled that secret ballot naturalization referendums could no longer be used (SI Appendix, Tables S1 and S2 provide details on the sample). These data give us a rich set of pretreatment covariates that determine the selection into citizenship conditional on applying. The covariates include the immigrants’ age, education, country of origin, years since arrival in Switzerland, and time period and municipality fixed effects.

To measure political integration, we conducted a survey of the immigrants included in the ref. 9 sample. The survey was conducted at the University of Zurich according to its policy for human subjects research. Informed consent was obtained from each participant at the beginning of the survey. Details about the survey are provided in the SI Appendix. Overall, we successfully identified and interviewed 768 immigrants, which corresponds to a cumulative response rate (RR3) as defined by the American Association for Public Opinion Research of 34.5% (45.9% among the competitive applicants with vote margins within ±15% around the threshold of winning). As we explain in the SI Appendix, this response rate is much higher than typical response rates for similar surveys.

One possible concern is that the probability of being interviewed is correlated with naturalization. SI Appendix, Fig. S2 and Table S3 show that this is not the case in our study. In fact, the probability of being interviewed and the characteristics of those interviewed are virtually identical for closely accepted and closely rejected immigrants.

Outcomes.

For the outcomes, we measured four standard indicators of political integration. The first outcome captures formal political participation and consists of a binary indicator coded as one for immigrants who report that they voted in the last federal parliamentary election in Switzerland and zero otherwise. Note that in Switzerland and most other democratic countries, a central feature of naturalization is that naturalized immigrants acquire the right to vote in federal elections (6). Because nonnaturalized immigrants do not have the right to vote, their turnout is legally constrained to be zero. Therefore, the effect of naturalization on turnout is constrained to be nonnegative, and so for this outcome, we are purely interested in the magnitude of the potential effect rather than the sign. In other words, the question is how commonly naturalized immigrants who are otherwise similar to nonnaturalized immigrants do actually exercise their newly acquired right to vote in Swiss federal elections or not.

The second outcome captures political efficacy using a standard question that asks respondents whether they agree with the statement that “people like me don’t have any influence on the government.” Answers are recorded on a five-point scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree,” and we standardized the codings to vary from 0 to 1 for comparability.

The third outcome captures political knowledge and is measured using the number of correct answers to two standard knowledge questions about the name of the current Swiss Federal President and the number of signatures required for a federal initiative. We again standardized the number of correct answers to vary from 0 to 1 for comparability.

The fourth outcome captures informal political participation. This outcome consists of a binary indicator that measures whether immigrants report that they participated in any of the following activities in the last 12 mo: contacted a politician, worked in a political party, displayed a campaign sticker, participated in a political demonstration, collected signatures for a petition, boycotted a product for political reasons, donated money to a political party, or persuaded others to vote.

As a final outcome, we also build a political integration scale that combines the four outcomes by extracting the first component of a polychoric principal component analysis (PCA) (15). This first component explains 51% of the total variance (Eigenvalue, 2.04). The SI Appendix provides details on the PCA. Averaging responses across multiple items is an effective strategy to reduce bias from random measurement error that is common in survey research. This strategy also provides a succinct summary measure for the multiple metrics of political integration. We calibrate the scale to have mean zero and a SD of 0.5 to make it comparable to the other outcomes.

It is worth emphasizing that one unique feature about our design is that it allows us to measure the long-term effects of naturalization. Because our survey was conducted in 2011–2014, and the use of naturalization referendums ended in 2003, for most applicants, there is a long gap between the time of the measure of the outcomes and the time of the receipt of Swiss citizenship (13 y on average). Our estimates, therefore, will pick up only lasting effects that naturalization might have on integrating immigrants into the political fabric of the host society. This rules out the possibility that our findings are driven by pure short-term effects, such as, for example, a temporary increase in political knowledge that results from applicants studying Swiss politics just to pass the application interview. To the best of our knowledge, there currently exists no causal evidence on the long-terms effects of naturalization.

Results

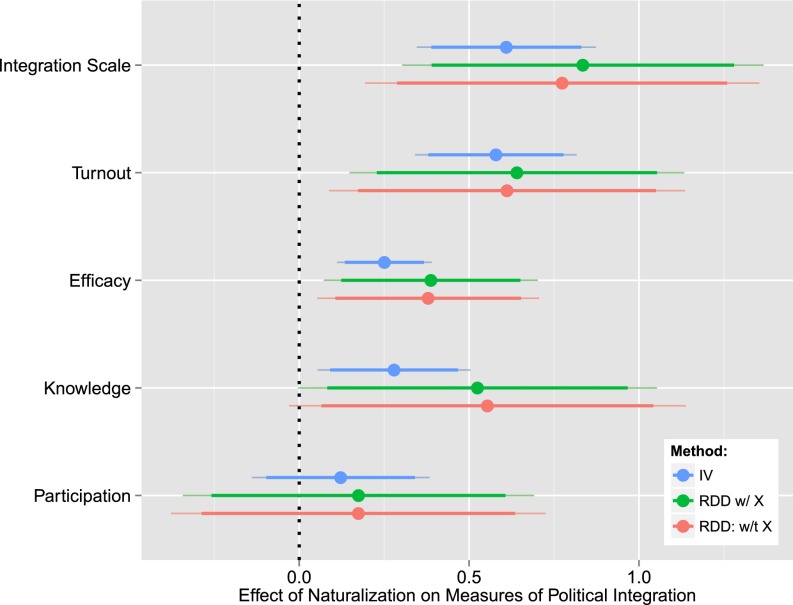

In Fig. 2, we present the effect estimates from the different identification strategies. In SI Appendix, Tables S5–S7, we report the regression tables. For all estimations, we restricted the sample to include only competitive applicants who obtained enough “yes” votes to come within a 15% window around the threshold of winning (i.e., applicants who scored between 35 and 65% of “yes” votes). In SI Appendix, Figs. S7–S9, we show that the estimates are fairly similar for different windows ranging from 10% to 25%. For smaller windows, our sample size is too limited to reliably estimate the treatment effect at the threshold with the fuzzy RD design.

Fig. 2.

Naturalization improves the political integration of immigrants. The figure shows point estimates and robust 95% (thin) and 90% (bold) confidence intervals from instrumental variable and fuzzy RD design models. Outcomes were as follows: political integration scale (mean, 0; SD, 0.5); voted in last election (0/1); political efficacy (0–1); political knowledge (0, 0.5, 1); and informal political participation (0/1). Covariates include reported applicant characteristics and fixed effects for municipality and time period. The sample includes all applicants within a window ±15% margin of the threshold.

Instrumental Variable Estimates.

To estimate the effect of naturalization, we fit two-stage least-squares models in which we regress the outcomes on a binary naturalization indicator, coded one for immigrants who received Swiss citizenship and zero for those who did not, and also control for the applicant background characteristics reported in the voting leaflets as well as a full set of municipality and time period fixed effects. We instrument the naturalization dummy with a binary instrument that codes whether immigrants won or lost their first naturalization referendum and were therefore encouraged to obtain or discouraged from obtaining Swiss citizenship.

We fit the first-stage equation by regressing naturalization status on the covariates, the vote margin, and the instrument (SI Appendix, Table S4). Consistent with Fig. 1, Lower Left, we find that the instrument has a strong effect on naturalization. Closely winning versus closely losing the first referendum increased the probability of obtaining Swiss citizenship by about 30 percentage points, and this finding is robust across a variety of specifications. This compliance ratio, which implies that there are about 30% compliers and about 70% always takers, is sufficiently high so that we avoid the problem of weak instruments [the F statistic for the relevance of the instrument is 20 for the preferred specification—which far exceeds the standard threshold of 10 (16)].

The blue estimates in Fig. 2 show the IV estimates of the effect of citizenship for compliers. We find that naturalization strongly improved the political integration of immigrants in our estimation sample. Comparing naturalized and nonnaturalized immigrants who were otherwise similar on the reported characteristics and therefore observably equivalent to voters, naturalization results in about a 0.61 increase in the political integration index that combines all of the integration outcomes (P < 0.0001, two-tailed). This effect is large in substantive terms: given that the index has a SD of 0.5, this means that naturalization boosted long-term political integration by about a full SD unit.

Looking at the outcomes separately, we see that the effects are consistent across measures. We find that newly naturalized immigrants who are otherwise similar to nonnaturalized immigrants had a turnout of 58 percentage points in the last parliamentary election in Switzerland. This level of voting is striking considering that the reported average turnout among rooted natives who have been Swiss since birth was 52% according to the Swiss election survey. This suggests that newly naturalized immigrants voted at similar rates as Swiss natives. We also find that naturalization has a strong effect on improving the political efficacy of immigrants with a 0.25 increase on the 0–1 scale of believing that one has an influence on the government. Given that the average level of efficacy among nonnaturalized immigrants is 0.44, this effect corresponds to about a 57% increase over the baseline level. Similarly, we find that naturalization resulted in immigrants becoming much more politically informed, with an increase of 0.28 on the 0–1 scale of answering the knowledge questions; this corresponds to about half of a question more answered correctly by naturalized immigrants or about a 104% increase over the average level of political knowledge among the nonnaturalized immigrants, which is 0.27. This increase is remarkable given that we interviewed respondents on the phone, when they were unprepared for the political quiz and could not easily look up the answers as in a self-completion survey. It is also remarkable given that naturalization raises immigrants’ average political knowledge to a level that is similar to that measured for rooted natives who have been Swiss since birth (which is about 0.52 according to the 2011 Selects survey that asked similar questions). Finally, we find that naturalization led to a 12 percentage point increase in informal political participation, but this effect is far from statistically significant at conventional levels (P < 0.36). This finding is partly attributable to the fact that most immigrants do not engage in informal participation, and therefore there is little variation in this outcome variable. For example, only 8% of the nonnaturalized immigrants engage in informal political participation.

Fuzzy RD Design Estimates.

The green estimates in Fig. 2 show the results from the fuzzy RD design that identifies the naturalization effect for compliers in close referendums based on local linear two-stage least-square regressions, where the slopes of the vote margin are allowed to vary on both sides of the threshold. The results are similar to the IV estimates, and the magnitudes are, if anything, slightly higher for all outcomes except informal participation. As expected, the RD estimates are less precise given the local identification for compliers at the threshold. Naturalization increases the political integration index by 0.83 (P < 0.002), the probability of voting by 64 percentage points, political efficacy by 0.39 (or 89% over the baseline level), and political knowledge by about 0.52 (or 193% over the baseline level). The effect on informal political participation is 17 percentage points and again far from significant at conventional levels (P < 0.49).

Finally, to check the design-based RD identification, the red estimates show the effects that we obtain when replicating the RD model while dropping all of the covariates (except the vote margin). If the naturalization decision in close referendums is as good as random, then just like in a randomized experiment, controlling or not controlling for the baseline covariates should not considerably change the effect estimates because the covariates (and also unobservables) are well balanced by design. The estimates are almost identical with and without the covariates, which corroborates the RD identification.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that naturalization caused large and long-lasting improvements in political integration among the competitive immigrant applicants in our sample. The results are consistent across the different identification strategies and various measures of political integration (except informal participation). These long-term increases in political integration are remarkable given that outcomes like voting, political efficacy, or political knowledge are often seen as fairly stable attributes that are formed in early socialization but then rarely change over time. However, among otherwise similar immigrants, naturalization substantially increases political engagement to a new level, where more than two decades later, naturalized immigrants vote at the same rates and possess similar levels of political information as rooted natives who have been Swiss since birth. This suggests that naturalization acts as a critical juncture where barely rejected immigrants remain disengaged from the political process, whereas barely accepted immigrants are propelled to become integrated to a level that is similar to that of rooted natives.

Discussion

Effect Heterogeneity.

One important question for policy and theory is whether the naturalization effect varies for different immigrant groups. To investigate this, we examined whether the naturalization effect differs by the origin of the immigrants, their level of education, and their prior residency in Switzerland. We find that the effects of naturalization are remarkably stable across these different groups of immigrants (SI Appendix, Tables S8–S13). Naturalization improved political integration for groups that are less socially marginalized to begin with, such as immigrants who are born in Switzerland, immigrants with higher education levels, and immigrants from richer European origin countries. However, we see similar naturalization effects among more socially marginalized groups, such as immigrants from Turkey and Yugoslavia, immigrants who are born abroad, and immigrants with lower education levels. This stability in the effects suggests that we might expect similar positive integration returns if the stringent residency requirements for naturalization were to be lowered.

Alienation or Integration.

Which mechanisms might be driving the naturalization effects? Although a full analysis of the mechanisms is clearly beyond the scope of this study, our data can shed some light on distinguishing between two broader mechanisms. One possibility is that the acquisition of citizenship turns immigrants into active and well-integrated participants of the democratic process. Another possibility is that the act of being rejected alienates applicants from the political process and the host country society such that the rejected applicants’ political integration drops lower than it would have been had they never applied for naturalization. Distinguishing these two mechanisms is difficult given that naturalization decisions always involve either an acceptance or rejection. However, one possibility is to examine outcomes that are especially sensitive to one specific mechanism. To test for a potential alienation effect, we replicate our models using three measures that capture the degree to which respondents distrust other people, the judicial system, or the local authorities (see the SI Appendix for details). If applicants are alienated because they are rejected on discriminatory grounds, then we would expect them to show higher levels of distrust than accepted applicants. This distrust would be directed either toward other people who cast the discriminatory votes in local referendums, the local authorities who processed the naturalization applications but did nothing to prevent the discrimination, or the courts who might have failed to overturn discriminatory rejections upon appeal. The findings, displayed in SI Appendix, Fig. S10, contradict the idea of a long-lasting alienation effect. Naturalization has no effect on all three distrust measures; point estimates are close to zero and insignificant. This suggests that the effects of naturalization work mainly through accepted immigrants becoming more politically integrated than they would be in the absence of naturalization, rather than through an alienation effect.

Conclusion

This study examined the long-term effect of Swiss citizenship on the political integration of immigrants. We exploited a natural experiment in that some municipalities used referendums to decide on naturalization requests of immigrants. This allowed us to isolate the effects of naturalization from the nonrandom selection into naturalization. Using two identification strategies and multiple outcomes and robustness checks, we found that in our sample of competitive applicants, naturalization has a strong effect in generating lasting improvements in political integration. Comparing among otherwise similar immigrants, those immigrants who barely won their referendums and therefore received the Swiss passport developed high levels of turnout, efficacy, and political knowledge similar to that of rooted natives, whereas those immigrants who barely lost their referendums and were therefore rejected to receive the Swiss passport remained fairly disengaged from the political process. These effects persist for more than a decade. The findings have important implications for the design of immigration and citizenship policy. The findings clearly support those who argue that naturalization has important independent effects in accelerating political integration and helps turn immigrants into “citizens” in the Tocquevillian sense. Moreover, the finding that the positive effects of naturalization on integration are stable across very different immigrant groups suggests that lowering the stringent residency requirements might be beneficial to realize the full integration gains from naturalizations. Clearly, more work is needed to identify the effects of citizenship in other contexts and for other outcomes. Further work is also needed to better ascertain the mechanisms through which naturalization increases political integration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Didier Ruedin, Duncan Lawrence, David Laitin, three anonymous reviewers, the editor, and seminar participants at Chicago, London, Oxford, Stanford, and Urbana–Champaign for their helpful comments; and Murat Aktas, Dejan Balaban, and Selina Kurer for excellent research assistance.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

†Noncompliance can only occur in the group of applicants who lost their first referendum, and therefore there are no “never takers” (i.e., applicants who never obtain citizenship) or “defiers” (i.e., applicants who obtain citizenship if they lose but not if they win). The one-sided noncompliance also implies that the LATE is equal to the average treatment effect on the untreated.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1418794112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bauböck R, Ersboll E, Groenendijk K, Waldrauch H. Acquisition and Loss of Nationality: Comparative Analyses-Policies and Trends in 15 European Countries. Vol 1 Amsterdam Univ Press; Amsterdam: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloemraad I. Becoming a Citizen: Incorporating Immigrants and Refugees in the United States and Canada. Univ of California Press; Los Angeles: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hochschild JL, Mollenkopf JH. Bringing outsiders in: Transatlantic perspectives on immigrant political incorporation. Cornell Univ Press; Ithaca, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dancygier RM, Laitin DD. Immigration into Europe: Economic discrimination, violence, and public policy. Annu Rev Polit Sci. 2014;17:43–64. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, ed (2011) Naturalisation: A Passport for the Better Integration of Immigrants? (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris)

- 6.Just A, Anderson CJ. Immigrants, citizenship and political action in Europe. Br J Polit Sci. 2012;42(3):481–509. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Portes A, Curtis JW. Changing flags: Naturalization and its determinants among Mexican immigrants. Int Migr Rev. 1987;21(2):352–371. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang PQ. Explaining immigrant naturalization. Int Migr Rev. 1994;28(3):449–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hainmueller J, Hangartner D. Who gets a Swiss passport? A natural experiment in immigrant discrimination. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2013;107(1):159–187. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hainmueller J, Hangartner D. Does direct democracy hurt immigrant minorities? evidence from naturalization decisions in Switzerland. Am J Pol Sci. 2015 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angrist JD, Imbens GW, Rubin DB. Identification of causal effects using instrumental variables. J Am Stat Assoc. 1996;91(434):444–455. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee DS. Randomized experiments from non-random selection in us house elections. J Econom. 2008;142(2):675–697. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hahn J, Todd P, Van der Klaauw W. Identification and estimation of treatment effects with a regression-discontinuity design. Econometrica. 2001;69(1):201–209. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCrary J. Manipulation of the running variable in the regression discontinuity design: A density test. J Econom. 2008;142(2):698–714. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olsson U. Maximum likelihood estimation of the polychoric correlation coefficient. Psychometrika. 1979;44(4):443–460. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stock JH, Yogo M. In: Testing for Weak Instruments in Liner IV Regression. Identification and Inference for Econometric Models. Stock J, Andrews DWK, editors. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 2005. pp. 80–108. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.