Abstract

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has, although it is a very common disorder, only relatively recently gained broader interest among physicians and scientists. Fatty liver has been documented in up to 10 to 15 percent of normal individuals and 70 to 80 percent of obese individuals. Although the pathophysiology of NAFLD is still subject to intensive research, several players and mechanisms have been suggested based on the substantial evidence. Excessive hepatocyte triglyceride accumulation resulting from insulin resistance is the first step in the proposed ‘two hit’ model of the pathogenesis of NAFLD. Oxidative stress resulting from mitochondrial fatty acids oxidation, NF-κB-dependent inflammatory cytokine expression and adipocytokines are all considered to be the potential factors causing second hits which lead to hepatocyte injury, inflammation and fibrosis. Although it was initially believed that NAFLD is a completely benign disorder, histologic follow-up studies have showed that fibrosis progression occurs in about a third of patients. A small number of patients with NAFLD eventually ends up with end-stage liver disease and even hepatocellular carcinoma. Although liver biopsy is currently the only way to confirm the NAFLD diagnosis and distinguish between fatty liver alone and NASH, no guidelines or firm recommendations can still be made as for when and in whom it is necessary. Increased physical activity, gradual weight reduction and in selected cases bariatric surgery remain the mainstay of NAFLD therapy. Studies with pharmacologic agents are showing promising results, but available data are still insufficient to make specific recommendations; their use therefore remains highly individual.

Keywords: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, Metabolic syndrome, Obesity, Insulin resistance, Liver fibrosis, NAFLD treatment

INTRODUCTION

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is an increasingly recognized cause of liver-related morbidity and mortality. It represents a spectrum of hepatic disorders characterized by macrovesicular steatosis that occur in the absence of alcohol consumption in amounts generally considered to be harmful to the liver (less than 40 g of ethanol per week). That spectrum ranges from simple hepatic steatosis without concomitant inflammation or fibrosis to hepatic steatosis with a necroinflammatory component that may or may not have associated fibrosis (non-alcoholic steatohepatitis-NASH) and can progress to cirrhosis.

Although the association of macrovesicular steatosis of the liver with inflammatory changes and fibrosis in obese subjects has been known for several decades, it was largely ignored as a clinical entity. The term “nonalcoholic steatohepatitis” was first introduced in 1980 by Ludwig et al and is used to describe the distinct clinical entity in which patients have liver biopsy findings indistinguishable from alcoholic hepatitis, but lack a history of significant alcohol consumption[1].

The true incidence and prevalence of NAFLD are unknown. Population-based studies most often use imaging modalities or serum alanine aminotransferase levels to diagnose NAFLD[2-4]. These studies are limited by the inability to make a definitive diagnosis of NAFLD or to distinguish between NAFLD and NASH, which requires liver biopsy. Studies that have used strict definitions for diagnosis including biopsies were most often based on specific subsets of the population (e.g. diabetics, obese individuals, in-hospital patients) and they cannot be applied to the general population[5-7]. Despite the limitations of the published data, several facts are consistently present. Fatty liver and NASH have been reported in all age groups, including children[4,8]. The prevalence increases with increasing body weight[6,9]. Fatty liver has been documented in up to 10% to 15% of normal individuals and 70% to 80% of obese individuals. Correspondingly, about 3% of normal individuals and 15% to 20% of morbidly obese subjects (BMI > 35 kg/m2) have steatohepatitis[6,10]. These findings are of particular concern given the increasing prevalence of obesity in virtually all age groups. The highest prevalence is in those between 40 and 60 years of age[7,11,12]. Although earlier studies found higher prevalence of NASH in women (65 to 85 percent of all patients), more recent studies have shown that NASH occurs with equal frequency in both sexes[1,7,11,13]. In the United States, there appear to be ethnic differences in the prevalence of NASH. A higher prevalence of hepatic steatosis was found in Hispanics (45%) compared with Caucasians (33%) or Afro-Americans (24%)[14].

There is increasing evidence that NAFLD represents the hepatic component of a metabolic syndrome characterized by obesity, hyperinsulinemia, peripheral insulin resistance, diabetes, hypertriglyceridemia, and hypertension. Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a major component of the metabolic syndrome and is associated with both obesity and NASH[1,12,13,15]. It has been described in 34% to 75% of patients with NASH. Diabetes is not only associated with NAFLD, but also may be a risk factor for development of progressive liver fibrosis[16]. Obesity has been reported in 70 to 100 percent of cases of NASH, and most patients are 10% to 40% above ideal body weight[1,12,13,15]. Numerous reports have documented resolution of fatty liver following gradual weight loss. Subjects with abdominal obesity are more prone to developing diabetes and hypertension as well as fatty liver. Hyperlipidemia (hypertriglyceridemia and/or hypercholesterolemia), which is frequently associated with both obesity and type 2 diabetes, has been reported in 20% to 80% of patients with NASH[1,12,13,15].

In addition, NAFLD has been associated with several rare disorders of lipid metabolism and insulin resistance (e.g. abetalipoproteinemia, lipoatrophic diabetes, Mauriac and Weber-Christian syndrome), as well as with total parenteral nutrition, acute starvation, intravenous glucose therapy, abdominal surgery (e.g. extensive small bowel resection, biliopancreatic diversion, and jejunal bypass), use of several drugs (e.g. amiodarone, tamoxifen, glucocorticoids, and synthetic estrogens) and several types of chemicals (e.g. organic solvents and dimethylformamide)[17-31]. The incidence, mechanism, and natural history of these forms of NAFLD are unknown.

Several studies reported that many patients with NASH have biochemical evidence of iron overload, with elevation of transferrin saturation and serum ferritin level. Patients with NASH were found to be homozygous or heterozygous for the Cys282Tyr mutation in the HFE gene in significantly higher percent than the general population. However, the hepatic iron index was < 1.9 in all patients. The presence of iron overload has been reported to be associated with increased hepatic fibrosis, but this finding was not confirmed by other reports. The significance of the HFE mutations in NASH remains to be fully established[32-36].

HOW DOES IT DEVELOP? – NAFLD PATHOGENESIS

A large body of evidence clearly indicates that NAFLD is principally associated with the metabolic syndrome. Therefore, two types of NAFLD can be recognized: primary NAFLD (associated with metabolic syndrome) and secondary NAFLD (associated with other specific metabolic or iatrogenic conditions distinct from the metabolic syndrome).

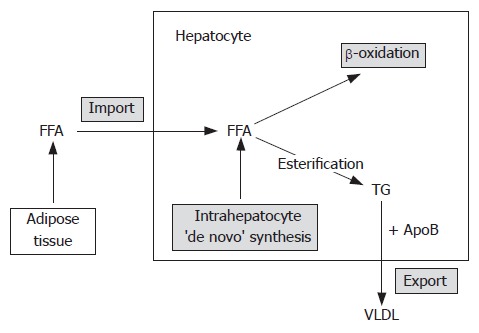

Pathophysiology of primary NAFLD still hasn’t been completely clarified. The so called ‘two hit’ model of the pathogenesis of NAFLD has been proposed since 1998[37]. Liver fat accumulation is the suggested ‘first hit’ or the first step. It is a consequence of excessive triglyceride accumulation caused by discrepancy between influx and synthesis of hepatic lipids on one side and their β-oxidation and export on the other (Figure 1)[38]. This imbalance occurs with all of the previously mentioned potential etiologic factors. The steatotic liver subsequently becomes vulnerable to presumed ‘second hits’ leading to hepatocyte injury, inflammation and fibrosis. The most widely supported theory implicates insulin resistance as the key mechanism in primary NAFLD, leading to hepatic steatosis, and perhaps also to steatohepatitis. The presumed factors initiating second hits are oxidative stress and subsequent lipid peroxidation, proinflammatory cytokines (principally TNF-α), and hormones derived from adipose tissue (adipocytokines) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Lipid metabolism within the hepatocytes. Liver lipid content is determined by the equilibrium of several processes: import of free fatty acids (FFAs) from the adipose tissue, de novo FFA synthesis in hepatocytes, beta-oxidation of FFAs, esterification of FFAs into triglycerides and export of triglycerides as very low density lipoproteins (VLDL). Hepatic steatosisis is a consequence of imbalance in those processes in favour of excessive triglyceride (TG) accumulation. FFA:free fatty acids; TG: triglycerides; VLDL: very low density lipoproteins; Apo B:apolipoprotein B.

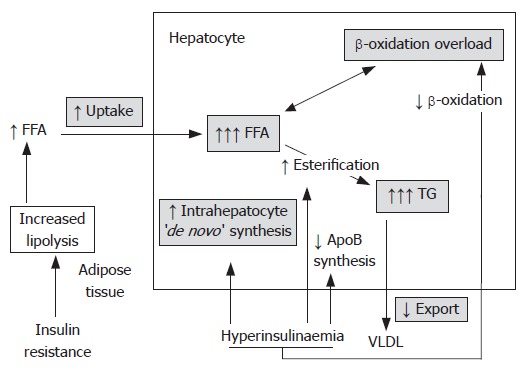

Obesity, type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia and other conditions associated with insulin resistance are generally present in patients with NAFLD. Insulin resistance has also been observed in patients with NAFLD who are not obese and in those with normal glucose tolerance[39-41]. The molecular mechanism leading to insulin resistance is complex and hasn’t been elucidated completely. Several molecules (tumor necrosis factor alpha, PC-1 membrane glycoprotein, leptin, and fatty acids) appear to interfere with the insulin signalling pathway[42]. Alterations in lipid metabolism associated with insulin resistance result from the interaction between the effects of insulin resistance located primarily in muscles and adipose tissue and impact of the compensatory hyperinsulinemia on tissues that remain insulin sensitive. These alterations include enhanced peripheral lipolysis, increased hepatic uptake of FFAs and increased hepatic triglyceride synthesis. FFA influx and neosynthesis outweigh FFA oxidation and triglyceride secretion, resulting in the net effect of hepatic fat accumulation. This can explain a key role of insulin resistance in the development of hepatic steatosis and, potentially, steatohepatitis (Figure 2)[43-48].

Figure 2.

Effects of insulin resistance on lipid metabolism. Insulin resistance and resulting hyperinsulinemia lead to hepatocyte lipid accumulation in the liver by several mechanisms. In adipose tissue, insulin resistance enhances triglyceride (TG) lipolysis and inhibits esterification of free fatty acids (FFAs). The result are increased circulating levels of FFAs, which are then taken up by the liver. Additionally, in hepatocytes hyperinsulinemia increases the ‘de novo’ synthesis of fatty acids and inhibits their beta oxidation. The consequence is accumulation of FFAs within hepatocytes. Hepatic TG synthesis is driven by the increased hepatocyte FFA content and favoured by insulin-mediated upregulation of lipogenic enzymes, such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) and sterol regulatory element binding protein 1 (SREBP-1). Meanwhile, reduced very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) production and TG export may be impaired by decreased synthesis of apolipoprotein B (apo B) or reduced binding of TG to apo B by microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP). The resulting accumulation of fat within the hepatocytes initiates further damage causing hepatic insulin resistance and reactive oxygen species production. (abbrevations: ↑ -icreased; ↓ -inhibits; FFA: free fatty acid; TG: triglyceride; VLDL: very low density lipoprotein; Apo B: apolipoprotein B.

The resulting accumulation of fat within the hepatocytes has several effects. FFAs impair insulin signalling and cause hepatic insulin resistance via mechanisms involving activation of PKC-3, JNK, I-κB kinase β (IKK-β) and NFκB[49,50]. Hepatic insulin resistance then increases mitochondrial fatty acids oxidation. Also, FFAs and their metabolites are ligands for peroxisomal proliferators-activated receptor-α (PPAR-α), the transcription factor that regulates the expression of different genes encoding enzymes involved in mitochondrial, peroxisomal and microsomal fatty acids oxidation. Finally, it appears that both consequences of fat accumulation within the liver (fat-induced hepatic insulin resistance and up-regulation of PPAR-α-regulated genes) result in increased FFA oxidation. Mitochondrial and peroxisomal fatty acids oxidation are both capable of producing hepatotoxic free oxygen radicals that contribute to the development of oxidative stress[51-54]. Considering all these data, it appears that insulin resistance could in fact deliver both ‘hits’ in the pathogenesis of NASH. Considerable mitochondrial structural abnormalities were found in patients with NASH, but not in those with simple hepatic steatosis[46,55-58]. It has also been found that several genes important for mitochondrial function were underexpressed in NASH patients[59]. Aforementioned oxidative stress and subsequent lipid peroxidation are the factors supposed to alter both mitochondrial DNA and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, leading to mitochondrial structural abnormalities and ATP depletion[60,61]. However, it is also possible that these mitochondrial abnormalities are the preexisting conditions that enable excessive free oxygen radical species production in the setting of enhanced FFA beta-oxidation[46]. This would mean that, in the absence of preexisting mitochondrial defects, insulin resistance will lead only to the development of simple hepatic steatosis.

Many studies demonstrated that oxidative stress is a prominent feature of NASH[62-64]. Apart from hepatocytes, ROS production and oxidative stress in obese patients can also originate in adipose tissue (both in adipocytes and in macrophages infiltrating adipose tissue)[65,66]. Inflammatory cells within the liver represent the third potential source of ROS and oxidative stress, especially in the setting of already developped steatohepatitis.

Hepatocyte reactive oxygen species accumulation (oxidative stress) could, at least to some extent, be responsible for further progression from steatosis to steatohepatitis and fibrosis. This could occur by three main mechanisms: lipid peroxidation, cytokine induction and Fas ligand induction. ROS-triggered lipid peroxidation of plasma or mitochondrial membranes causes cell necrosis or induces apoptosis. Lipid peroxidation also initiates release of malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) that can bind to hepatocyte proteins forming neoantigens and initiating a potentially harmful immune response, cross-link cytokeratins to form Mallory hyaline, or activate hepatic stellate cells promoting collagen synthesis and stimulate neutrophil chemotaxis[62,67]. ROS also increases expression of Fas-ligand on hepatocytes that interacts with normally expressed membrane receptor Fas on the adjacent hepatocytes causing apoptotic cell death[68]. ROS may also initiate the activation of the transcription factor NF-κB, which leads to increased production of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, TGF-β, IL-6, IL-8)[69].

Furthermore, there are convincing data that inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β) also play an important role in the pathogenesis of NAFLD[70]. They may cause systemic and hepatic insulin resistance[71]. They also cause hepatocyte injury and apoptosis, neutrophil chemotaxis, and hepatic stellate cell activation[72-74]. Crespo et al have found that obese patients with NASH compared to those without it have significantly increased liver expression of TNF-α and its receptor p55, as well as increased expression of TNF-α in adipose tissue[75]. This increased expression correlated with the degree of liver fibrosis. FFAs accumulated in hepatocytes stimulate NF-κB-dependent inflammatory cytokine expression (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β)[76,77]. Kupffer cells are, as the liver specific macrophages, also a potent source of proinflammatory cytokines. Activating stimulus could be hepatocyte-derived cytokines, clearance of oxidated lipid deposits via scavenger receptors[70], or gut-derived endotoxins in patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth[78]. Finally, adipose tissue is in obese people infiltrated by macrophages[65], making it another possible source of proinflammatory cytokines[75,79]. It appears that cytokines produced by adipose tissue macrophages (particularly TNF-α) could mediate systemic and hepatic insulin resistance[71], as well as cause a reduction in the secretion of the protective adipocytokine adiponectin[80].

Adipocytokines are peptides produced by visceral adipose tissue. Among them, adiponectin and leptin are directly involved in different metabolic and inflammatory pathways and could be particularly important in the pathogenesis of NAFLD. Adiponectin appears to have a pivotal role in improving fatty acid oxidation and decreasing fatty acid synthesis[81]. Liver and muscle cells have adiponectin receptors. Stimulation of adiponectin receptors in the liver leads to the activation of PPAR-α and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)[82-84]. Consequently, adiponectin increases fatty acid β-oxidation and thereby decreases hepatic triglyceride content and hepatic insulin resistance. Adiponectin also has a direct anti-inflammatory effect, suppressing TNF-α production in the liver[80,81]. Recent studies showed reduced serum levels of adiponectin and reduced hepatic expression of its receptor in patients with NASH compared to those with simple steatosis[85,86]. It seems that increased production of TNF-α and the generation of ROS are the ones responsible for the reduction in adiponectin secretion[66,80]. This again implicates that TNF-α and ROS-mediated suppression of adiponectin may play an important role in the pathogenesis of progressive NAFLD. A study in obese leptin-deficient mice demonstrated significant improvements in hepatic steatosis, hepatomegaly, and aminotransferase levels following administration of adiponectin[81].

Leptin is another peptide produced in adipose tissue that may have an important role in the development of insulin resistance. Leptin inactivates insulin receptor substrate (dephosphorylation of insulin-receptor substrate 1) inducing peripheral and hepatic insulin resistance[87]. Blood leptin levels correlate with the degree of fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C[88]; however Angulo et al have found no correlation between leptin levels and stage of liver fibrosis in a study of 88 patients with NAFLD[89]. Cohen et al have found that leptin, at the levels comparable with those present in obese individuals, induces hepatic insuline resistance by dephosphorylation of insulin-receptor substrate 1[87].

In the end, hepatocyte injury and associated inflam-mation will lead to the activation of hepatic stellate cells and synthesis of extracellular matrix proteins with liver fibrosis as the final consequence. In addition, apoptotic cell death is also of great importance in hepatic fibrogenesis[68]. It leads to stellate cell activation by the means of ingestion of apoptosing hepatocytes by Kupffer cells and subsequent release of TGF-β[90,91]. There are several more mediators possibly involved in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis in NAFLD. The adipocytokine leptin may play a role in fibrogenesis[89,92]. The reduced production of adiponectin associated with obesity may also contribute to the development of liver fibrosis[93]. Angiotensin II, which is also secreted by adipose tissue and is raised in the serum of obese patients, stimulates hepatic stellate cells and thus has profibrogenic effect[94]. Finally, hyperglycaemia and hyperinsulinaemia associated with insulin resistance are also suggested to be the key-factors in the progression of fibrosis through the up-regulation of the synthesis connective tissue growth factor by stellate cells[95].

Despite all of the recent advances in understanding the pathogenesis of NAFLD, the reason why only a minority of patients with classical risk factors for NAFLD develop more than simple steatosis still remains largely unclear (Figure 2).

WHAT TO EXPECT FOR THE PATIENT? - NATURAL HISTORY AND CLINICAL COURSE OF NAFLD

In spite of the increasing interest and significant progress in understanding of NAFLD, its natural history still hasn’t been clearly defined. The reason for this is mostly the lack of large prospective histologic follow-up studies. However, some concepts are clear: NASH progresses to cirrhosis less frequently than alcoholic steatohepatitis, with significantly better long-term survival of NASH patients[96,97].

Nevertheless, in a population-based study that used data from a large long-term epidemiology project, patients with NAFLD had a slightly higher mortality than the general population[98]. Liver-related death was the third most common cause of mortality in those patients, compared to the thirteenth place of liver-related death in the general population[98]. Another retrospective study of 132 patients found that poor outcomes (cirrhosis and liver-related mortality) occurred in 22 percent of patients in whom initial biopsies showed ballooning degeneration and Mallory hyaline or fibrosis, compared to 4 percent in patients with steatosis alone[97].

There has been a lot of speculation about the rate of progression of disease. Initial studies with paired biopsies showed histologic progression in 30% to 50% of NASH patients, but they had limited conclusions due to small patient numbers[12,15,99,100].

The largest reported series of NAFLD patients with sequential liver biopsies published in 2005 included 103 patients with a mean interval of 3.2 years between biopsies[101]. Fibrosis stage progressed in 37%, remained stable in 34% and regressed in 29% of patients. Diabetes, low initial fibrosis stage and higher body mass index were associated with higher rate of fibrosis progression. Another study of 22 patients with a median 4.3-year interval between biopsies also found progression of fibrosis in about a third of patients, with obesity and higher body mass index being the only associated factors[102].

According to these results it is obvious that NAFLD, and especially NASH, is not a completely benign condition as it was initially believed. Now it is clear that it may lead to end-stage liver disease, and small number of patients with NAFLD may eventually end up with liver transplantation. Interestingly, steatosis and steatohepatitis recurrence after liver transplantation has been described[103]. Furthermore, several studies suggest that hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) might also be among possible NAFLD outcomes[104-106]. Further studies are required before the risk of HCC in NAFLD can be more precisely defined.

HOW TO DIAGNOSE? - THE ROLE OF THE LIVER BIOPSY

Most patients with NAFLD come to medical attention due to an accidental finding of elevated liver function tests. Although aminotransferase levels are elevated in the majority of patients, normal values don’t exclude the presence of necroinflammatory changes or fibrosis. That was best illustrated in a study of 51 subjects with normal ALT levels where 12 had bridging fibrosis and 6 had cirrhosis[107].

In the longitudinal histologic study of 103 patients aminotransferase improvement correlated with improvement in activity grade, but change in aminotransferase levels did not correlate with a change in fibrosis stage. Interestingly, aminotransferase levels decreased significantly between biopsies both in patients with progressive fibrosis as well as in those without it[101].

Imaging methods are of little value in diagnostic evaluation of NAFLD. Finding of hyperechoic liver on ultrasonography is frequent in NAFLD, but it is neither sensitive nor specific enough. Moreover, all of the three most commonly used imaging methods (US, CT, MRI) have been shown to be incapable of differentiating between NASH and other forms of NAFLD[108].

The role of the liver biopsy in NAFLD has been widely discussed, and correlation between histologic findings and clinical features or disease prognosis extensively studied. Liver biopsy is currently the only way to confirm diagnosis of NAFLD and distinguish between fatty liver alone and NASH. It also permits determination of disease severity and possibly gives insight into prognosis. Nevertheless, no guidelines or firm recommendations can yet be made as for when and in whom is liver biopsy necessary.

Another problem with liver biopsy is that it has several significant limitations. First, the quality of liver biopsy specimens is variable. Furthermore, studies have shown significant inter- and intra-observer variability in biopsy specimen interpretation[109,110]. Additionally, it has long been known that affection of liver parenchyma in various chronic liver diseases is not homogenous, and biopsy is, therefore, subject to sampling variability[111]. This has also been proven for NASH in a study in which two liver biopsies were performed in 51 patients with NAFLD[112]. None of the histological features displayed high agreement between two samples from the same patient. Six of 17 patients (35%) with bridging fibrosis on one sample had only mild or no fibrosis on the other and, therefore, could have been understaged with only one biopsy. The negative predictive value of a single biopsy for the diagnosis of NASH was at best 0.74, and discordance of one or more stages was 41%.

In order to overcome some of the frequently present difficulties in liver biopsy interpretation, Matteoni et al divided NAFLD into four categories or types, based on the presence of steatosis, lobular inflammation, hepatocyte ballooning and Mallory bodies/fibrosis[97]. Types 3 and 4 were associated with worse clinical outcomes. The first histological scoring system for NASH was proposed by Brunt et al and it was designed based on a model used in other chronic liver diseases and included 3 qualitatively assessed grades of necroinflammatory activity (based on degree of steatosis, balooning and inflammation) and 4 stages of fibrosis[113]. However, it didn’t include the whole spectrum of NAFLD and it couldn’t be used in assessment of response to therapy. Therefore, another scoring system has been developed, which specifically includes only features of active injury that are potentially reversible in the short term[110]. The score, named NAS (NAFLD Activity Score), is the unweighted sum of the scores for steatosis (0-3), lobular inflammation (0-3), and ballooning (0-2), while fibrosis was not included. The primary purpose of NAS is to assess overall histological change; it wasn’t designed to replace the pathologist’s determination of steatohepatitis, nor to represent an absolute severity scale.

In spite of all the efforts, there is still no international consensus regarding the histopathological criteria that would firmly define non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and differentiate between NAFLD entities. Therefore, a large amount of confusion between pathologists and clinicans is still present. As an illustration, in NAS development study interrater agreement on the diagnosis of steatohepatitis was 0.61, and only 68% of liver biopsies with steatosis, ballooning and lobular inflammation all present were diagnosed as NASH[110].

Several clinical and biochemical risk factors for progressive disease have been identified, as they could potentially facilitate patient selection for liver biopsy. In one study, age over 45, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and aspartate transaminase/alanine transaminase (AST/ALT) ratio greater than 1 were significant predictors of severe liver fibrosis[16]. In another study, age over 50 years, BMI over 28, triglycerides over 1.7 mmol/L and alanine aminotransferase more than two times normal were independently associated with septal fibrosis[114].

In conclusion, for the time being, the decision to perform liver biopsy remains highly individual, as well as the interpretation of the histopathologic finding.

AVAILABLE TREATMENT OPTIONS

NAFLD, a hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome, is emerging as the most common clinically important form of liver disease in obese patients[9,14]. Obesity, along with insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia, is a central risk factor for NAFLD. Lifestyle modifications, which should include long-term weight management through induction of negative calorie balance (primarily reducing dietary carbohydrate and saturated fat intake), regular physical exercise with maintenance of weight loss and cognitive-behavior programs are the mainstays of the successful therapy of metabolic syndrome. Specific diet and exercise guidelines for NAFLD patients have not been established, but several types of diets have been proposed for treatment of obesity by different medical and commercial sources[115-117]. Although the published results of several studies in NAFLD population are mostly insufficient due to their small sample size, they have reported that short term weight loss with concomitant exercise leads to improvement in liver biochemical tests and to resolution of hepatic steatosis[118-120]. Moderate weight loss with incorporated regular physical activity is advocated in contrast to rapid weigh loss, which could aggravate the underlying liver disease. A recent study showed that weight reduction of 5 or more percent accompanied by regular exercise (at least twice a week) for one year were associated with improvement and normalization in ALT levels[121]. Keeping this weight (< 5% gain) for two consecutive years was associated with maintaining normal ALT levels. Another recent study reported that intense dietary intervention can achieve a reduction in mean waist circumference, insulin resistance, levels of fasting glucose, triglycerides and liver function tests, as well as an improvement in liver histology in patients with NASH[122].

Pharmacological treatment should be initiated only when there is no change in the course of disease after adequate lifestyle changes have been undertaken. The problem is that appropriate diet and physical activity, in addition to behavioral modifications, are not always successful, particularly in very obese NAFLD patients. A pilot study, which included ten obese NASH patients treated with weight-loss drug orlistat (inhibitor of pancreatic and gastric lipase) for 6 mo, showed that 10% or greater consequent body weight reduction leads to improvement in aminotransferase levels, liver steatosis and fibrosis[123].

Bariatric surgery is considered to be the best therapeutic modality in NAFLD patients with severe obesity or with concomitant obesity-associated morbidities, like sleep apnea syndrome[124]. There are different surgical approaches to morbidly obese patients: malabsorptive procedures, such as jejuno-ileal bypass and biliopancreatic diversions, and restricitive procedures, which include gastric bypass and gastroplasty (gastric banding). Jejuno-ileal bypass, as the more ‘classical’ procedure, has been virtually replaced by ‘newer’ procedures such as proximal gastric bypass and biliopancretic diversion, mostly due to the high frequency of postoperative complications[125,126]. Those included progression of liver disease, although, occasional cases of NASH progression and subacute liver failure have also been reported with ‘newer’ methods. Several recent trials reported that moderate or even massive weight loss with consequent mild to moderate malnutrition after gastroplasty in severe obese NASH patients resulted in improvement in diabetes mellitus, liver function tests and liver histology (inflammation and fibrosis)[124,127-130]. Similar results were reported after gastric bypass surgery[20]. Even though these promising results give a new perspective on treatment of severely obese NAFLD patients, the decision to perform surgery should still be individual.

The role of smoking and minimal to moderate alcohol intake in pathogenesis and potential progression of NAFLD has not been widely investigated; therefore, specific recommendations regarding those factors cannot be made.

Lipid-lowering agents

A one year pilot study, which evaluated a lipid-lowering drug clofibrate in the treatment of 16 patients with hypertriglyceridemia and NASH, revealed no significant changes in levels of aminotransferases or liver histology[132]. A controlled trial of a 4-wk treatment in 46 patients with NASH, using gemfibrozil 600 mg/d, resulted in a significant improvement in liver tests, although the study did not include liver biopsies[133]. A total of 56 patients with NAFLD/NASH and hyperlipidemia was investigated in three separate studies and received 3-hydroxy-3-metylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG CoA) reductase inhibitor atorvastatin (10-80 mg/d) for 6-12 mo, which lead to significant improvement or normalization in serum aminotransferase and lipids/cholesterol levels, as well as in the degree of inflammation, ballooning and Mallory bodies on liver histology[134-136]. A small study using another HMG CoA reductase inhibitor pravastatin included 5 patients with biopsy proven NASH[137]. After 6 mo of pravastatin treatment cholesterol levels were reduced, with normalization of liver function tests but without improvement in the fibrosis score.

Metformin

Metformin is an insulin-sensitizing agent that reportedly reversed hepatomegaly, steatosis and liver tests abnormalities in an animal model of fatty liver[138]. First pilot study which investigated metformin treatment (500 mg three times daily) in patients with NASH suggested association of usage of this agent with improvement in liver tests and index of insulin sensitivity, as well as decrease in hepatic volume[139]. A possible benefit of metformin in the induction of normalization of liver tests and loss of body weight was reported after 6 mo of therapy in a preliminary report of an open-label study of 15 patients[140]. However, consequent results after 1 year of treatment showed no effect on aminostransferase levels, liver histology, or insulin sensitivity[141]. Another randomized controlled study in patients with NAFLD reported that addition of metformin to a lipid and calorie-restricted diet vs diet alone for 6 mo lead to improvement in mean serum aminotransferase levels and insulin resistance. On the other hand, no statistically significant change in the severity of liver inflammation or fibrosis at the end of the treatment period was reported[142]. Higher rates of aminotransferase normalization and improvement in liver histology and insulin sensitivity were associated with metformin treatment in comparison to vitamin E treatment or weight loss in an open-label randomized study of 110 non-diabetic patients[143].

Thiazolidinediones

Thiazolidinediones (pioglitazone, rosiglitazone), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) gamma ligands, are insulin-sensitizing drugs involved in glucose and lipid metabolism with suggested anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic properties[144]. They are a new class of antidiabetic agents investigated recently as a potential treatment modality for patients with NAFLD/NASH. PPARγ agonist pioglitazone prevents the activation of hepatic stellate cells in vitro, and improves hepatic steatosis and prevents liver fibrosis in vivo[145]. In another study with animals 1 wk treatment with pioglitazone inhibited hepatic fat accumulation and decreased levels of TNFα, while 4 wk treatment lead to improvement in hepatic fibrosis with a decrease in the expression of procollagen, alpha-smooth muscle actin, and TGF-β1[146]. In the first of prospective human studies, 48 wk of pioglitazone treatment (30 mg daily) of nondiabetic patients with biopsy-proven NASH improved the degree of insulin sensitivity with normalization of aminotransferase levels and histological improvement in hepatic steatosis, cellular injury, parenchymal inflammation, Mallory bodies, and fibrosis[147]. MRI confirmed a marked decrease in liver fat and liver volume, but interestingly, increase in body weight and total body fat was observed. In another controlled study combination treatment with pioglitazone (30 mg daily) and vitamin E (400 IU daily) normalized aminotransferase levels, but the effect was also seen in the control group treated with vitamin E alone[148]. However, only combination therapy induced a significant effect on histological findings (decrease in steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning, Mallory’s bodies and pericellular fibrosis), with improvement in metabolic disturbances (increase in metabolic clearance of glucose and a decrease in fasting free fatty acid and insulin). A recent study proposed that improvements seen on liver histology after pioglitazone therapy may be the effect of change in adiponectin levels[149]. In another study of rosiglitazone in 25 NASH patients of whom half had diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance, 1-year therapy was associated with improvement in liver function tests, insulin sensitivity and degree of fibrosis[150]. Opposite to these promising results, the latest meta-analysis of 42 trials with rosiglitazone found that the drug was associated with significant increase in the risk of myocardial infarction[151]. Considering all this, recommendations about use of thiazolidinediones in NAFLD treatment can not be yet established.

Losartan

A role for angiotensin II in pathogenesis of hepatic stellate cell activation, hepatic inflammation and fibrogenesis has been postulated[152-156]. Given the potential therapeutic effects of angiotensin II receptor antagonists, studies with losartan were performed in patients with NASH and arterial hypertension[157-159]. Reduction in levels of blood markers of hepatic fibrosis, transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and ferritin concentration was reported, with improvement in serum aminotransferase levels. Reduction of hepatic necroinflammation, fibrosis and iron hepatocyte deposition was detected in the majority of liver biopsy specimens after 48 wk of treatment. Results suggest anti-fibrotic effect of losartan through inhibitory effect on hepatic stellate cell activation. These promising initial results justify further studies of angiotensin II receptor antagonists in treatment of NAFLD patients.

Antioxidants

Oxidative stress, along with the insulin resistance, plays one of the essential roles in NAFLD pathogenesis. Therefore, treatment with different antioxidants (vitamin E, vitamin C, betaine, iron depletion) has been studied in this group of patients. A study with vitamin E administration (300 mg/d during 1 year) confirmed improvement in liver tests with reduction of plasma levels of TGF-β1, but revealed no change in degree of steatosis, fibrosis and inflammation on follow-up liver biopsy[160]. A placebo-controlled trial of a combination of vitamin E (1000 IU/daily) and vitamin C (1000 mg/d) during 6 mo showed no statistically significant difference between vitamin and placebo groups in liver enzyme levels, degree of steatosis and inflammatory activity, or fibrosis score, although an improvement in fibrosis was noted in the vitamin group[161]. Given the suggested protective effect of betaine against steatosis in rats (through increase of S-adenosylmethionine levels), a pilot study was performed in 8 patients with NASH[162]. After one year treatment with betaine (20 mg daily), a significant improvement or normalization in serum aminotransferase levels and liver histology was noted. Another placebo-controlled study included 191 patients with NAFLD treated for 8 wk with combination of betaine glucuronate (300 mg/d), diethanolamine and nicotinamide ascorbate[163]. Significant improvement was noted in liver tests and degree of steatosis (evaluated by ultrasonography) in the treated group. Further controlled trials are needed for confirmation of these promising results. It has been hypothesized that iron induces oxidative stress by catalyzing production of ROS (reactive oxygen species) and increased hepatic iron deposition could be a part of the pathogenesis of NAFLD[164]. In a few pilot studies in NASH patients, quantitative phlebotomies were performed with induction of iron depletion and reduction in serum ferritin levels[165-167]. Results of these studies suggest that iron reduction therapy by phlebotomy can lead to improvement in aminotransferase levels; unfortunately, follow-up liver biopsies were not performed.

Ursodeoxycholic acid

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) could potentially act as a hepatoprotective agent by minimizing toxicity of hydrophobic bile acids and leading to a decrease in oxidative stress and hepatocyte injury. Initial small pilot-studies evaluated therapeutic effect of UDCA alone or in combination with low-fat diet or lipid-lowering agents in patients with NASH[132,135,168-170]. Results suggested potential benefit of UDCA treatment with reported normalization/improvement in liver function tests, degree of hepatic steatosis and serum markers of fibrosis. However, consequent larger, randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled trial found no detectable benefit of UDCA treatment: similar degree of improvement in biochemistry and histology was detected in both study groups[171]. Given the lack of effectiveness of UDCA alone as a therapeutic option in NASH, one recent study considered combination of UDCA with vitamin E. Significantly diminished levels of serum aminotransferases were observed, with improvement in histological activity index, mostly as a result of regression of steatosis[172].

CONCLUSION

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is currently the object of significant scientific and clinical interest, and is to remain so in the following years. Larger studies with firm inferences are rather scarce, and their small number reflects the difficulties in setting-up and performing clinical trials in NAFLD. Among the most important obstacles that researchers are confronted with are slowly progressive nature of the disease requiring long-term follow-up, variability in liver biopsy specimens and their interpretation, various associated conditions and multiple medication use that are common in these patients. Although clinicians dispose in theory with a wide array of possible therapies, few have been shown to have consistent effects and can therefore be firmly recommended in treatment of NAFLD.

Footnotes

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Rippe RA E- Editor Liu Y

References

- 1.Ludwig J, Viggiano TR, McGill DB, Oh BJ. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Mayo Clinic experiences with a hitherto unnamed disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1980;55:434–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franzese A, Vajro P, Argenziano A, Puzziello A, Iannucci MP, Saviano MC, Brunetti F, Rubino A. Liver involvement in obese children. Ultrasonography and liver enzyme levels at diagnosis and during follow-up in an Italian population. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:1428–1432. doi: 10.1023/a:1018850223495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nomura H, Kashiwagi S, Hayashi J, Kajiyama W, Tani S, Goto M. Prevalence of fatty liver in a general population of Okinawa, Japan. Jpn J Med. 1988;27:142–149. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine1962.27.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tazawa Y, Noguchi H, Nishinomiya F, Takada G. Serum alanine aminotransferase activity in obese children. Acta Paediatr. 1997;86:238–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb08881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nasrallah SM, Wills CE, Galambos JT. Hepatic morphology in obesity. Dig Dis Sci. 1981;26:325–327. doi: 10.1007/BF01308373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersen T, Christoffersen P, Gluud C. The liver in consecutive patients with morbid obesity: a clinical, morphological, and biochemical study. Int J Obes. 1984;8:107–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teli MR, James OF, Burt AD, Bennett MK, Day CP. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver: a follow-up study. Hepatology. 1995;22:1714–1719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baldridge AD, Perez-Atayde AR, Graeme-Cook F, Higgins L, Lavine JE. Idiopathic steatohepatitis in childhood: a multicenter retrospective study. J Pediatr. 1995;127:700–704. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellentani S, Saccoccio G, Masutti F, Crocè LS, Brandi G, Sasso F, Cristanini G, Tiribelli C. Prevalence of and risk factors for hepatic steatosis in Northern Italy. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:112–117. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-2-200001180-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wanless IR, Lentz JS. Fatty liver hepatitis (steatohepatitis) and obesity: an autopsy study with analysis of risk factors. Hepatology. 1990;12:1106–1110. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840120505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bacon BR, Farahvash MJ, Janney CG, Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: an expanded clinical entity. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1103–1109. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powell EE, Cooksley WG, Hanson R, Searle J, Halliday JW, Powell LW. The natural history of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a follow-up study of forty-two patients for up to 21 years. Hepatology. 1990;11:74–80. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840110114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diehl AM, Goodman Z, Ishak KG. Alcohollike liver disease in nonalcoholics. A clinical and histologic comparison with alcohol-induced liver injury. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:1056–1062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Browning JD, Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins R, Nuremberg P, Horton JD, Cohen JC, Grundy SM, Hobbs HH. Prevalence of hepatic steatosis in an urban population in the United States: impact of ethnicity. Hepatology. 2004;40:1387–1395. doi: 10.1002/hep.20466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee RG. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a study of 49 patients. Hum Pathol. 1989;20:594–598. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(89)90249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Angulo P, Keach JC, Batts KP, Lindor KD. Independent predictors of liver fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 1999;30:1356–1362. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Partin JS, Partin JC, Schubert WK, McAdams AJ. Liver ultrastructure in abetalipoproteinemia: Evolution of micronodular cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1974;67:107–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powell EE, Searle J, Mortimer R. Steatohepatitis associated with limb lipodystrophy. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:1022–1024. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)91513-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah SS, Desai HG. Apolipoprotein deficiency and chronic liver disease. J Assoc Physicians India. 2001;49:274–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robertson DA, Wright R. Cirrhosis in partial lipodystrophy. Postgrad Med J. 1989;65:318–320. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.65.763.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cauble MS, Gilroy R, Sorrell MF, Mailliard ME, Sudan DL, Anderson JC, Wisecarver JL, Balakrishnan S, Larsen JL. Lipoatrophic diabetes and end-stage liver disease secondary to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis with recurrence after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2001;71:892–895. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200104150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wasserman JM, Thung SN, Berman R, Bodenheimer HC, Sigal SH. Hepatic Weber-Christian disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2001;21:115–118. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poucell S, Ireton J, Valencia-Mayoral P, Downar E, Larratt L, Patterson J, Blendis L, Phillips MJ. Amiodarone-associated phospholipidosis and fibrosis of the liver. Light, immunohistochemical, and electron microscopic studies. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:926–936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pessayre D, Bichara M, Degott C, Potet F, Benhamou JP, Feldmann G. Perhexiline maleate-induced cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1979;76:170–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pratt DS, Knox TA, Erban J. Tamoxifen-induced steatohepatitis. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:236. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-3-199508010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinez E, Mocroft A, García-Viejo MA, Pérez-Cuevas JB, Blanco JL, Mallolas J, Bianchi L, Conget I, Blanch J, Phillips A, et al. Risk of lipodystrophy in HIV-1-infected patients treated with protease inhibitors: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2001;357:592–598. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kotler DP, Engleson ES. The lowdown on lipodystrophy. Special report from the 2nd International Workshop on Adverse Drug Reactions and Lipodystrophy. Posit Living. 2001;10:5–6, 17, 32-33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rakotoambinina B, Médioni J, Rabian C, Jubault V, Jais JP, Viard JP. Lipodystrophic syndromes and hyperlipidemia in a cohort of HIV-1-infected patients receiving triple combination antiretroviral therapy with a protease inhibitor. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;27:443–449. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200108150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herman JS, Easterbrook PJ. The metabolic toxicities of antiretroviral therapy. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12:555–562; quiz 563-564. doi: 10.1258/0956462011923714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Valk M, Bisschop PH, Romijn JA, Ackermans MT, Lange JM, Endert E, Reiss P, Sauerwein HP. Lipodystrophy in HIV-1-positive patients is associated with insulin resistance in multiple metabolic pathways. AIDS. 2001;15:2093–2100. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200111090-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cotrim HP, Andrade ZA, Parana R, Portugal M, Lyra LG, Freitas LA. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a toxic liver disease in industrial workers. Liver. 1999;19:299–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.1999.tb00053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.George DK, Goldwurm S, MacDonald GA, Cowley LL, Walker NI, Ward PJ, Jazwinska EC, Powell LW. Increased hepatic iron concentration in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is associated with increased fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:311–318. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70482-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonkovsky HL, Jawaid Q, Tortorelli K, LeClair P, Cobb J, Lambrecht RW, Banner BF. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and iron: increased prevalence of mutations of the HFE gene in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:421–429. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Younossi ZM, Gramlich T, Bacon BR, Matteoni CA, Boparai N, O'Neill R, McCullough AJ. Hepatic iron and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 1999;30:847–850. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sonsuz A, Basaranoglu M, Ozbay G. Relationship between aminotransferase levels and histopathological findings in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1370–1371. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Itoh S, Yougel T, Kawagoe K. Comparison between nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and alcoholic hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:650–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Day CP, James OF. Steatohepatitis: a tale of two "hits"? Gastroenterology. 1998;114:842–845. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Donnelly KL, Smith CI, Schwarzenberg SJ, Jessurun J, Boldt MD, Parks EJ. Sources of fatty acids stored in liver and secreted via lipoproteins in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1343–1351. doi: 10.1172/JCI23621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chitturi S, Abeygunasekera S, Farrell GC, Holmes-Walker J, Hui JM, Fung C, Karim R, Lin R, Samarasinghe D, Liddle C, et al. NASH and insulin resistance: Insulin hypersecretion and specific association with the insulin resistance syndrome. Hepatology. 2002;35:373–379. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marchesini G, Bugianesi E, Forlani G, Cerrelli F, Lenzi M, Manini R, Natale S, Vanni E, Villanova N, Melchionda N, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver, steatohepatitis, and the metabolic syndrome. Hepatology. 2003;37:917–923. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim HJ, Kim HJ, Lee KE, Kim DJ, Kim SK, Ahn CW, Lim SK, Kim KR, Lee HC, Huh KB, et al. Metabolic significance of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in nonobese, nondiabetic adults. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2169–2175. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.19.2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Angulo P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1221–1231. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra011775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moller DE, Flier JS. Insulin resistance--mechanisms, syndromes, and implications. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:938–948. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199109263251307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kotzka J, Müller-Wieland D. Sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP)-1: gene regulatory target for insulin resistance? Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2004;8:141–149. doi: 10.1517/14728222.8.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Charlton M, Sreekumar R, Rasmussen D, Lindor K, Nair KS. Apolipoprotein synthesis in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2002;35:898–904. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.32527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanyal AJ, Campbell-Sargent C, Mirshahi F, Rizzo WB, Contos MJ, Sterling RK, Luketic VA, Shiffman ML, Clore JN. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: association of insulin resistance and mitochondrial abnormalities. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1183–1192. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.23256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pagano G, Pacini G, Musso G, Gambino R, Mecca F, Depetris N, Cassader M, David E, Cavallo-Perin P, Rizzetto M. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome: further evidence for an etiologic association. Hepatology. 2002;35:367–372. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marchesini G, Brizi M, Morselli-Labate AM, Bianchi G, Bugianesi E, McCullough AJ, Forlani G, Melchionda N. Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with insulin resistance. Am J Med. 1999;107:450–455. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Samuel VT, Liu ZX, Qu X, Elder BD, Bilz S, Befroy D, Romanelli AJ, Shulman GI. Mechanism of hepatic insulin resistance in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32345–32353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313478200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cai D, Yuan M, Frantz DF, Melendez PA, Hansen L, Lee J, Shoelson SE. Local and systemic insulin resistance resulting from hepatic activation of IKK-beta and NF-kappaB. Nat Med. 2005;11:183–190. doi: 10.1038/nm1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robertson G, Leclercq I, Farrell GC. Nonalcoholic steatosis and steatohepatitis. II. Cytochrome P-450 enzymes and oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G1135–G1139. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.5.G1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Emery MG, Fisher JM, Chien JY, Kharasch ED, Dellinger EP, Kowdley KV, Thummel KE. CYP2E1 activity before and after weight loss in morbidly obese subjects with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2003;38:428–435. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chalasani N, Gorski JC, Asghar MS, Asghar A, Foresman B, Hall SD, Crabb DW. Hepatic cytochrome P450 2E1 activity in nondiabetic patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2003;37:544–550. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reddy JK. Nonalcoholic steatosis and steatohepatitis. III. Peroxisomal beta-oxidation, PPAR alpha, and steatohepatitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G1333–G1339. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.6.G1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pessayre D, Fromenty B. NASH: a mitochondrial disease. J Hepatol. 2005;42:928–940. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Caldwell SH, Swerdlow RH, Khan EM, Iezzoni JC, Hespenheide EE, Parks JK, Parker WD. Mitochondrial abnormalities in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:430–434. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cortez-Pinto H, Chatham J, Chacko VP, Arnold C, Rashid A, Diehl AM. Alterations in liver ATP homeostasis in human nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a pilot study. JAMA. 1999;282:1659–1664. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.17.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pérez-Carreras M, Del Hoyo P, Martín MA, Rubio JC, Martín A, Castellano G, Colina F, Arenas J, Solis-Herruzo JA. Defective hepatic mitochondrial respiratory chain in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2003;38:999–1007. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sreekumar R, Rosado B, Rasmussen D, Charlton M. Hepatic gene expression in histologically progressive nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2003;38:244–251. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hruszkewycz AM. Evidence for mitochondrial DNA damage by lipid peroxidation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;153:191–197. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)81207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen J, Schenker S, Frosto TA, Henderson GI. Inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase activity by 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE). Role of HNE adduct formation with the enzyme subunits. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1380:336–344. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(98)00002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Albano E, Mottaran E, Vidali M, Reale E, Saksena S, Occhino G, Burt AD, Day CP. Immune response towards lipid peroxidation products as a predictor of progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease to advanced fibrosis. Gut. 2005;54:987–993. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.057968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seki S, Kitada T, Yamada T, Sakaguchi H, Nakatani K, Wakasa K. In situ detection of lipid peroxidation and oxidative DNA damage in non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2002;37:56–62. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Letteron P, Fromenty B, Terris B, Degott C, Pessayre D. Acute and chronic hepatic steatosis lead to in vivo lipid peroxidation in mice. J Hepatol. 1996;24:200–208. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(96)80030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1796–1808. doi: 10.1172/JCI19246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Furukawa S, Fujita T, Shimabukuro M, Iwaki M, Yamada Y, Nakajima Y, Nakayama O, Makishima M, Matsuda M, Shimomura I. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1752–1761. doi: 10.1172/JCI21625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zamara E, Novo E, Marra F, Gentilini A, Romanelli RG, Caligiuri A, Robino G, Tamagno E, Aragno M, Danni O, et al. 4-Hydroxynonenal as a selective pro-fibrogenic stimulus for activated human hepatic stellate cells. J Hepatol. 2004;40:60–68. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00480-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Feldstein AE, Canbay A, Angulo P, Taniai M, Burgart LJ, Lindor KD, Gores GJ. Hepatocyte apoptosis and fas expression are prominent features of human nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:437–443. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00907-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ribeiro PS, Cortez-Pinto H, Solá S, Castro RE, Ramalho RM, Baptista A, Moura MC, Camilo ME, Rodrigues CM. Hepatocyte apoptosis, expression of death receptors, and activation of NF-kappaB in the liver of nonalcoholic and alcoholic steatohepatitis patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1708–1717. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cortez-Pinto H, de Moura MC, Day CP. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: from cell biology to clinical practice. J Hepatol. 2006;44:197–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arkan MC, Hevener AL, Greten FR, Maeda S, Li ZW, Long JM, Wynshaw-Boris A, Poli G, Olefsky J, Karin M. IKK-beta links inflammation to obesity-induced insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2005;11:191–198. doi: 10.1038/nm1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nagai H, Matsumaru K, Feng G, Kaplowitz N. Reduced glutathione depletion causes necrosis and sensitization to tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced apoptosis in cultured mouse hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2002;36:55–64. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ding WX, Yin XM. Dissection of the multiple mechanisms of TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis in liver injury. J Cell Mol Med. 2004;8:445–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2004.tb00469.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pessayre D, Berson A, Fromenty B, Mansouri A. Mitochondria in steatohepatitis. Semin Liver Dis. 2001;21:57–69. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Crespo J, Cayón A, Fernández-Gil P, Hernández-Guerra M, Mayorga M, Domínguez-Díez A, Fernández-Escalante JC, Pons-Romero F. Gene expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha and TNF-receptors, p55 and p75, in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis patients. Hepatology. 2001;34:1158–1163. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.29628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Feldstein AE, Werneburg NW, Canbay A, Guicciardi ME, Bronk SF, Rydzewski R, Burgart LJ, Gores GJ. Free fatty acids promote hepatic lipotoxicity by stimulating TNF-alpha expression via a lysosomal pathway. Hepatology. 2004;40:185–194. doi: 10.1002/hep.20283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tripathy D, Mohanty P, Dhindsa S, Syed T, Ghanim H, Aljada A, Dandona P. Elevation of free fatty acids induces inflammation and impairs vascular reactivity in healthy subjects. Diabetes. 2003;52:2882–2887. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.12.2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wigg AJ, Roberts-Thomson IC, Dymock RB, McCarthy PJ, Grose RH, Cummins AG. The role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, intestinal permeability, endotoxaemia, and tumour necrosis factor alpha in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Gut. 2001;48:206–211. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.2.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS. Obesity-induced inflammatory changes in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1785–1788. doi: 10.1172/JCI20514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Maeda N, Shimomura I, Kishida K, Nishizawa H, Matsuda M, Nagaretani H, Furuyama N, Kondo H, Takahashi M, Arita Y, et al. Diet-induced insulin resistance in mice lacking adiponectin/ACRP30. Nat Med. 2002;8:731–737. doi: 10.1038/nm724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xu A, Wang Y, Keshaw H, Xu LY, Lam KS, Cooper GJ. The fat-derived hormone adiponectin alleviates alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases in mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:91–100. doi: 10.1172/JCI17797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Waki H, Terauchi Y, Kubota N, Hara K, Mori Y, Ide T, Murakami K, Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N, et al. The fat-derived hormone adiponectin reverses insulin resistance associated with both lipoatrophy and obesity. Nat Med. 2001;7:941–946. doi: 10.1038/90984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Minokoshi Y, Ito Y, Waki H, Uchida S, Yamashita S, Noda M, Kita S, Ueki K, et al. Adiponectin stimulates glucose utilization and fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Nat Med. 2002;8:1288–1295. doi: 10.1038/nm788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Ito Y, Tsuchida A, Yokomizo T, Kita S, Sugiyama T, Miyagishi M, Hara K, Tsunoda M, et al. Cloning of adiponectin receptors that mediate antidiabetic metabolic effects. Nature. 2003;423:762–769. doi: 10.1038/nature01705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hui JM, Hodge A, Farrell GC, Kench JG, Kriketos A, George J. Beyond insulin resistance in NASH: TNF-alpha or adiponectin? Hepatology. 2004;40:46–54. doi: 10.1002/hep.20280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kaser S, Moschen A, Cayon A, Kaser A, Crespo J, Pons-Romero F, Ebenbichler CF, Patsch JR, Tilg H. Adiponectin and its receptors in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Gut. 2005;54:117–121. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.037010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cohen B, Novick D, Rubinstein M. Modulation of insulin activities by leptin. Science. 1996;274:1185–1188. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Crespo J, Rivero M, Fábrega E, Cayón A, Amado JA, García-Unzeta MT, Pons-Romero F. Plasma leptin and TNF-alpha levels in chronic hepatitis C patients and their relationship to hepatic fibrosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:1604–1610. doi: 10.1023/a:1015835606718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Angulo P, Alba LM, Petrovic LM, Adams LA, Lindor KD, Jensen MD. Leptin, insulin resistance, and liver fibrosis in human nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2004;41:943–949. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Canbay A, Taimr P, Torok N, Higuchi H, Friedman S, Gores GJ. Apoptotic body engulfment by a human stellate cell line is profibrogenic. Lab Invest. 2003;83:655–663. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000069036.63405.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Konowal A, Freed PW, Westcott JY, Henson PM. Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells in vitro inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production through autocrine/paracrine mechanisms involving TGF-beta, PGE2, and PAF. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:890–898. doi: 10.1172/JCI1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Leclercq IA, Farrell GC, Schriemer R, Robertson GR. Leptin is essential for the hepatic fibrogenic response to chronic liver injury. J Hepatol. 2002;37:206–213. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Targher G, Bertolini L, Rodella S, Zoppini G, Scala L, Zenari L, Falezza G. Associations between plasma adiponectin concentrations and liver histology in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2006;64:679–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bataller R, Schwabe RF, Choi YH, Yang L, Paik YH, Lindquist J, Qian T, Schoonhoven R, Hagedorn CH, Lemasters JJ, et al. NADPH oxidase signal transduces angiotensin II in hepatic stellate cells and is critical in hepatic fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1383–1394. doi: 10.1172/JCI18212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Paradis V, Perlemuter G, Bonvoust F, Dargere D, Parfait B, Vidaud M, Conti M, Huet S, Ba N, Buffet C, et al. High glucose and hyperinsulinemia stimulate connective tissue growth factor expression: a potential mechanism involved in progression to fibrosis in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2001;34:738–744. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.28055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cortez-Pinto H, Baptista A, Camilo ME, De Moura MC. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis--a long-term follow-up study: comparison with alcoholic hepatitis in ambulatory and hospitalized patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1909–1913. doi: 10.1023/a:1026152415917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Matteoni CA, Younossi ZM, Gramlich T, Boparai N, Liu YC, McCullough AJ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a spectrum of clinical and pathological severity. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1413–1419. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70506-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Adams LA, Lymp JF, St Sauver J, Sanderson SO, Lindor KD, Feldstein A, Angulo P. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:113–121. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Evans CD, Oien KA, MacSween RN, Mills PR. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a common cause of progressive chronic liver injury? J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:689–692. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.9.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Harrison SA, Torgerson S, Hayashi PH. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a clinical histopathological study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2042–2047. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Adams LA, Sanderson S, Lindor KD, Angulo P. The histological course of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a longitudinal study of 103 patients with sequential liver biopsies. J Hepatol. 2005;42:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fassio E, Alvarez E, Domínguez N, Landeira G, Longo C. Natural history of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a longitudinal study of repeat liver biopsies. Hepatology. 2004;40:820–826. doi: 10.1002/hep.20410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kim WR, Poterucha JJ, Porayko MK, Dickson ER, Steers JL, Wiesner RH. Recurrence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis following liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1996;62:1802–1805. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199612270-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Marrero JA, Fontana RJ, Su GL, Conjeevaram HS, Emick DM, Lok AS. NAFLD may be a common underlying liver disease in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Hepatology. 2002;36:1349–1354. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bugianesi E, Leone N, Vanni E, Marchesini G, Brunello F, Carucci P, Musso A, De Paolis P, Capussotti L, Salizzoni M, et al. Expanding the natural history of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: from cryptogenic cirrhosis to hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:134–140. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.El-Serag HB, Tran T, Everhart JE. Diabetes increases the risk of chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:460–468. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mofrad P, Contos MJ, Haque M, Sargeant C, Fisher RA, Luketic VA, Sterling RK, Shiffman ML, Stravitz RT, Sanyal AJ. Clinical and histologic spectrum of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease associated with normal ALT values. Hepatology. 2003;37:1286–1292. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Saadeh S, Younossi ZM, Remer EM, Gramlich T, Ong JP, Hurley M, Mullen KD, Cooper JN, Sheridan MJ. The utility of radiological imaging in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:745–750. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Younossi ZM, Gramlich T, Liu YC, Matteoni C, Petrelli M, Goldblum J, Rybicki L, McCullough AJ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: assessment of variability in pathologic interpretations. Mod Pathol. 1998;11:560–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, Behling C, Contos MJ, Cummings OW, Ferrell LD, Liu YC, Torbenson MS, Unalp-Arida A, et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;41:1313–1321. doi: 10.1002/hep.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Abdi W, Millan JC, Mezey E. Sampling variability on percutaneous liver biopsy. Arch Intern Med. 1979;139:667–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ratziu V, Charlotte F, Heurtier A, Gombert S, Giral P, Bruckert E, Grimaldi A, Capron F, Poynard T. Sampling variability of liver biopsy in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1898–1906. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Brunt EM, Janney CG, Di Bisceglie AM, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Bacon BR. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a proposal for grading and staging the histological lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2467–2474. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ratziu V, Giral P, Charlotte F, Bruckert E, Thibault V, Theodorou I, Khalil L, Turpin G, Opolon P, Poynard T. Liver fibrosis in overweight patients. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:1117–1123. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70364-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Executive summary of the clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1855–1867. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.17.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Krauss RM, Eckel RH, Howard B, Appel LJ, Daniels SR, Deckelbaum RJ, Erdman JW, Kris-Etherton P, Goldberg IJ, Kotchen TA, et al. AHA Dietary Guidelines: revision 2000: A statement for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee of the American Heart Association. Stroke. 2000;31:2751–2766. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.11.2751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Clark MJ, Sterrett JJ, Carson DS. Diabetes guidelines: a summary and comparison of the recommendations of the American Diabetes Association, Veterans Health Administration, and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Clin Ther. 2000;22:899–910; discussion 898. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(00)80063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Palmer M, Schaffner F. Effect of weight reduction on hepatic abnormalities in overweight patients. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:1408–1413. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)91169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ueno T, Sugawara H, Sujaku K, Hashimoto O, Tsuji R, Tamaki S, Torimura T, Inuzuka S, Sata M, Tanikawa K. Therapeutic effects of restricted diet and exercise in obese patients with fatty liver. J Hepatol. 1997;27:103–107. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80287-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wang RT, Koretz RL, Yee HF. Is weight reduction an effective therapy for nonalcoholic fatty liver? A systematic review. Am J Med. 2003;115:554–559. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00449-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Suzuki A, Lindor K, St Saver J, Lymp J, Mendes F, Muto A, Okada T, Angulo P. Effect of changes on body weight and lifestyle in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2005;43:1060–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Huang MA, Greenson JK, Chao C, Anderson L, Peterman D, Jacobson J, Emick D, Lok AS, Conjeevaram HS. One-year intense nutritional counseling results in histological improvement in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a pilot study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1072–1081. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Harrison SA, Fincke C, Helinski D, Torgerson S, Hayashi P. A pilot study of orlistat treatment in obese, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:623–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Shaffer EA. Bariatric surgery: a promising solution for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in the very obese. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40 Suppl 1:S44–S50. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000168649.79034.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Campbell JM, Hunt TK, Karam JH, Forsham PH. Jejunoileal bypass as a treatment of morbid obesity. Arch Intern Med. 1977;137:602–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Luyckx FH, Desaive C, Thiry A, Dewé W, Scheen AJ, Gielen JE, Lefèbvre PJ. Liver abnormalities in severely obese subjects: effect of drastic weight loss after gastroplasty. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22:222–226. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Dixon JB, Bhathal PS, Hughes NR, O'Brien PE. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Improvement in liver histological analysis with weight loss. Hepatology. 2004;39:1647–1654. doi: 10.1002/hep.20251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Stratopoulos C, Papakonstantinou A, Terzis I, Spiliadi C, Dimitriades G, Komesidou V, Kitsanta P, Argyrakos T, Hadjiyannakis E. Changes in liver histology accompanying massive weight loss after gastroplasty for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2005;15:1154–1160. doi: 10.1381/0960892055002239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Dixon JB, Bhathal PS, O'Brien PE. Weight loss and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: falls in gamma-glutamyl transferase concentrations are associated with histologic improvement. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1278–1286. doi: 10.1381/096089206778663805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Jaskiewicz K, Raczynska S, Rzepko R, Sledziński Z. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease treated by gastroplasty. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:21–26. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-3077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Barker KB, Palekar NA, Bowers SP, Goldberg JE, Pulcini JP, Harrison SA. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: effect of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:368–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Laurin J, Lindor KD, Crippin JS, Gossard A, Gores GJ, Ludwig J, Rakela J, McGill DB. Ursodeoxycholic acid or clofibrate in the treatment of non-alcohol-induced steatohepatitis: a pilot study. Hepatology. 1996;23:1464–1467. doi: 10.1002/hep.510230624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Basaranoglu M, Acbay O, Sonsuz A. A controlled trial of gemfibrozil in the treatment of patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:384. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Horlander JC, Kwo PY, Cummings OW, Koukoulis G. Atorvastatin for the treatment of NASH. Gastroenterology. 2001;120 suppl:2767. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Kiyici M, Gulten M, Gurel S, Nak SG, Dolar E, Savci G, Adim SB, Yerci O, Memik F. Ursodeoxycholic acid and atorvastatin in the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2003;17:713–718. doi: 10.1155/2003/857869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Gómez-Domínguez E, Gisbert JP, Moreno-Monteagudo JA, García-Buey L, Moreno-Otero R. A pilot study of atorvastatin treatment in dyslipemid, non-alcoholic fatty liver patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1643–1647. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Rallidis LS, Drakoulis CK, Parasi AS. Pravastatin in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: results of a pilot study. Atherosclerosis. 2004;174:193–196. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Lin HZ, Yang SQ, Chuckaree C, Kuhajda F, Ronnet G, Diehl AM. Metformin reverses fatty liver disease in obese, leptin-deficient mice. Nat Med. 2000;6:998–1003. doi: 10.1038/79697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Marchesini G, Brizi M, Bianchi G, Tomassetti S, Zoli M, Melchionda N. Metformin in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Lancet. 2001;358:893–894. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Nair S, Diehl AM, Perrillo RP. Metformin in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): efficacy and safety – a preliminary report. Gastroenterology. 2002;122 suppl:4. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Nair S, Diehl AM, Wiseman M, Farr GH, Perrillo RP. Metformin in the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a pilot open label trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:23–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]